Journal of Comprehensive Nursing Research and Care Volume 9 (2024), Article ID: JCNRC-201

https://doi.org/10.33790/jcnrc1100201Research Article

Longitudinal Relationship Between Physical Activity Levels and Respiratory Function in Older Individuals : A Longitudinal Study

Makoto Suzuki1*, and Takaaki Ikeda2

1 Department of Occupational Therapy, Faculty of Health Sciences, Bukkyo University, Kyoto, Japan.

2 Department of Health Policy Science, Graduate School of Medical Science, Yamagata University, Yamagata, Japan.

Corresponding Author Details: Makoto Suzuki, Department of Occupational Therapy, Faculty of Health Sciences, Bukkyo University, Kyoto, Japan.

Received date: 29th July, 2024

Accepted date: 16th August, 2024

Published date: 19th August, 2024

Citation: Suzuki, M., & Ikeda, T., (2024). Longitudinal Relationship Between Physical Activity Levels and Respiratory Function in Older Individuals: A Longitudinal Study. J Comp Nurs Res Care 9(2):201.

Copyright: ©2024, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Abstract

Aging causes various physical changes, including decreased respiratory function characterized by decreased lung elasticity, reduced chest wall compliance, and weakened respiratory muscles. This study explored the longitudinal impact of daily physical activity (PA) on respiratory function in elderly individuals aged ≥50 years in England. Using data from Waves 2 (2004–2005), 4 (2008–2009), and 6 (2012–2013), we examined the influence of different levels of PA on forced expiratory volume (FEV), forced vital capacity (FVC), and other respiratory measures. Participants were classified based on self-reported PA into three categories; “hard” (vigorous activity at least 1–3 times monthly), “middle” (moderate activity 1–3 times monthly), and “nothing” (no PA). The inclusion criteria required participants to be ≥50 years and to have valid respiratory measures. The exclusion criterion was the presence of significant respiratory or cardiovascular disease at baseline. We applied the Sequential Doubly Robust Estimator and SuperLearner ensemble methods in the analysis using inverse probability weighting to address follow up bias and found that vigorous PA significantly reduced the risk of FVC by 4.10-fold compared with no exercise. In addition, vigorous exercise was associated with a 0.63-fold reduction in the risk of restrictive ventilation disorders while moderate exercise approached significance for FVC (p = 0.08). No significant effects were found with obstructive ventilation impairment (FEV). Overall, vigorous PA appears to be crucial for maintaining respiratory function in older individuals, highlighting the importance of regular exercise in preventing respiratory decline and potentially extending a healthy lifespan. These results underscore the need to promote regular PA to improve quality of life and reduce the risk of respiratory disease.

Keywords: Respiratory Function, Physical Activity, Vital Capacity, Aging, Forced Expiratory Volume

Introduction

Physical function changes with age, including decreased muscle strength and cognitive decline [1]. Decreased respiratory function includes decreased lung elasticity, reduced chest wall compliance, and weakened respiratory muscles [2]. Functionally, while the total lung capacity remains unchanged or decreases slightly, the residual volume and vital capacity (VC) decrease [3]. Declined respiratory function increases the risk of developing life-threatening conditions, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), which can cause acute myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, and aspiration pneumonia [4-6]. Moreover, smoking is considered a risk factor for increased residual volume and decreased vital capacity, exacerbating respiratory decline. These conditions often necessitate changes in lifestyle and diet, and preventing respiratory function decline is therefore crucial for improving the quality of life (QOL) and extending a healthy lifespan.

Respiratory function is related to the quality and intensity of exercises performed. The relationship between the type and intensity of physical activity (PA) and its quantitative effects on lung function have been studied, revealing that different exercises have varying effects on respiratory health [6-9]. A cross-sectional study by Cheng et al. found that individuals with higher PA levels had a higher forced expiratory volume (FEV) and forced VC (FVC), although no significant difference was found in the forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1)/FVC ratio [10]. A longitudinal analysis showed that the patients who remained active or became active had better maximal treadmill test results than those who remained sedentary; however, the participants in this study were 25–55 years old. A meta-analysis of 22 studies indicated that continuous aerobic exercise improved FVC and FEV in patients with asthma, but not the FEV1/FVC ratio [11]. Studies focusing on diseases, such as COPD and rare diseases [12,13], have shown changes based on specific conditions, but longitudinal research remains insufficient on the relationship between exercise habits, exercise intensity, and respiratory function in older individuals from a preventive perspective. Demonstrating that daily exercise can prevent age-related decline in respiratory function in older individuals could provide significant insights into extending healthy lifespans. However, no large-scale studies have proven this using extensive data.

Therefore, this study aimed to elucidate the effect of daily PA levels on respiratory function in individuals aged ≥50 years in England.

Research Design and Participants

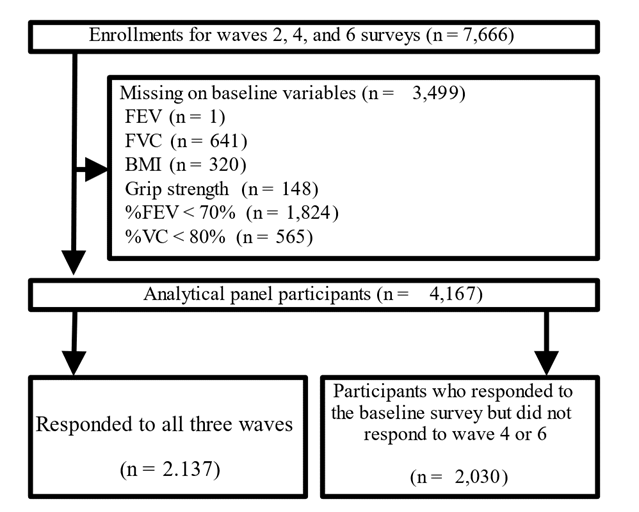

This longitudinal study used data from the English Longitudinal Study of Aging (ELSA) [14], a national survey of aging in England conducted biennially (in waves). The sample was obtained from participants of the Health Survey in England (HSE). Survey items assessed health, social status, happiness, and economic status. This study used Wave 2 (2004–2005) as the baseline to create panel data for Waves 4 (2008–2009) and 6 (2012–2013). The baseline sample of Wave 2 nurse data included 7,666 individuals, excluding those with missing values for FEV (n = 1), FVC (n = 641), BMI (n = 320), and grip strength (n = 148). Additionally, individuals with an FEV1/FVC ratio of <70% (n = 1,824) and percentage VC (%VC) of <80% (n = 565) were excluded, resulting in 4,167 participants (Figure 1).

Variables and Data Collection

The primary exposure variable was self-reported PA level, which was categorized into three levels: no exercise, moderate-intensity exercise, and hard-intensity exercise. Outcome variables were FEV, FVC, %FEV, and %VC. The FEV represents the volume of air that an individual can forcefully exhale in 1 s and is a critical measure of respiratory function. A lower FEV may indicate impaired respiratory function. FVC measures the total volume of air exhaled after deep inhalation and is used to evaluate lung capacity; a decrease in FVC suggests restrictive lung disease (American Thoracic Society, 1995). The percentage of FEV (%FEV) compares the FEV of an individual to the predicted value based on demographic factors such as age, sex, height, and ethnicity, which helps in assessing deviations from the expected respiratory function. Similarly, the %VC compares an FVC of an individual with the predicted value, providing insights into respiratory health relative to the expected norms [15].

Specific cutoff values or thresholds for these outcome variables were used to categorize the levels of respiratory impairment or disease. These cut-off values are typically determined based on clinical guidelines and population norms. Precise definitions and standard cut-offs are provided in guidelines from the American Thoracic Society [16] and European Respiratory Society [17], which offer standard reference values for spirometric measurements and interpretative criteria.

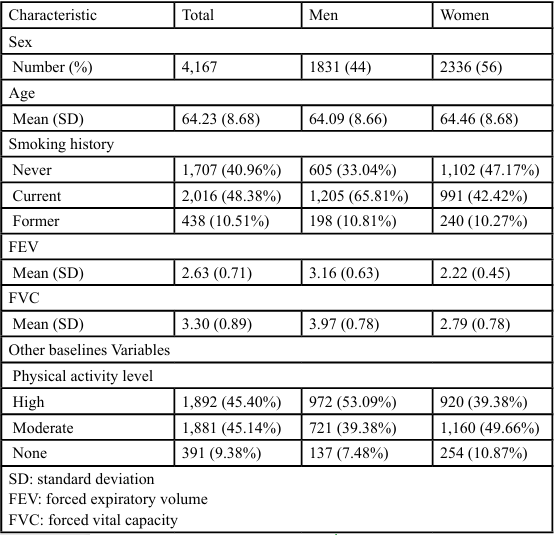

Data were collected using self-reported questionnaires and respiratory function measurement devices. The PA was used as the exposure factor. To assess PA, we used two types of self-reported PA records for each wave, including the frequency of engaging in vigorous (riding, cycling, aerobics) or moderate exercise (walking at a moderate pace, gardening), categorized as more than once weekly, once weekly, 1–3 times monthly, hardly ever, or no monthly activity. The PA questionnaire was derived from a validated PA interview conducted during the HSE [18]. Based on the results and previous studies [19], three categories of PA were used: “hard” (vigorous PA, regardless of moderate activity, at least 1–3 times monthly), “middle” (moderate PA only, 1–3 times monthly), and “nothing” (no PA at all). This study compared individuals who engaged in no exercise and those who engaged in vigorous or moderate exercise in waves 2–6 (Table 1). Outcomes were binary variables based on whether the %VC and FEV at wave 6 exceeded or fell below the threshold values for restrictive (<80%) or obstructive (<70 %) ventilatory disorders.

Statistical Analysis

The analysis model used a sequential doubly robust estimator (SDR) for causal and statistical inferences. The SDR calculates the conditional probability of the outcome provided by the exposure and covariates (exposure model) and the exposure provided by the covariates (outcome model), producing unbiased results if either model is consistently estimated [19,20]. Given the complexity of selecting an optimal algorithm for model specification, we used the “SuperLearner” package, an ensemble machine learning method, to combine different algorithms for the best predictive model [21]. The SuperLearner algorithm set included generalized linear models, multivariate adaptive regression splines, random forests, and extreme gradient-boosted trees as candidate estimators [22-24]. The best algorithms were used for the exposure and outcome models.

The SDR model was compared to calculate the relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CIs) for various counterfactual scenarios. Statistical analyses were performed using R (4.2.3 for Windows). All waves of the ELSA received Ethical Approval from the National Research Ethics Committee and all participants provided informed consent.

Results

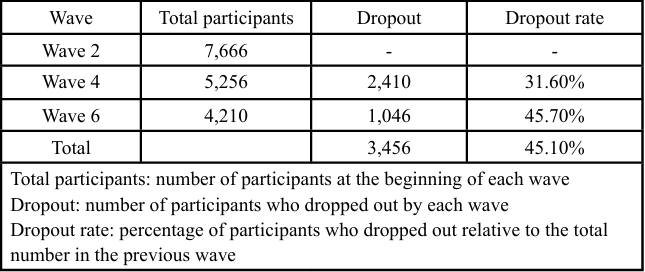

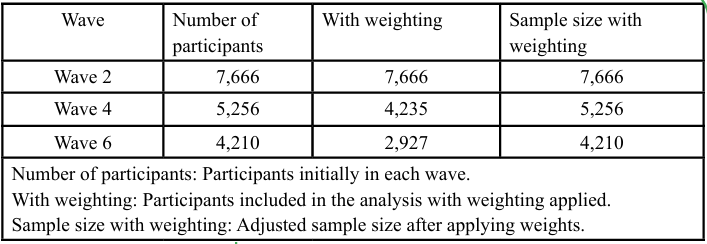

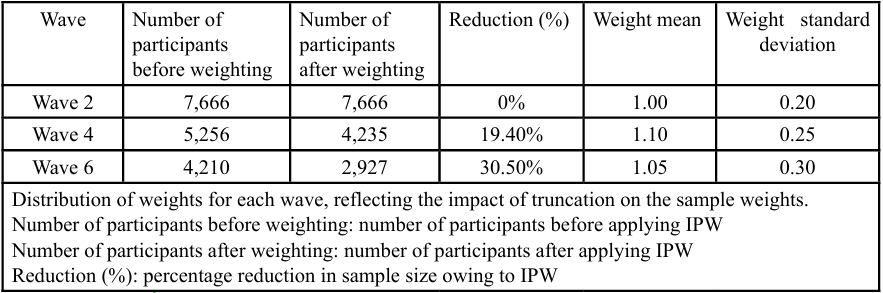

To address follow-up bias due to participant dropout during the study, inverse probability weighting (IPW) with truncation was used for samples that dropped out or had died in Waves 4 (n = 1,507) and 6 (n = 2,030, including 1,507 participants in Wave 4). Dropout rates were significant across the study waves. Specifically, the dropout rate was 31.60% from Waves 2 to 4 and 45.70% from Waves 4 to 6. The total dropout rate across all waves was 45.10%. Table 2 presents the dropout status of participants across different waves. Wave 2 contained 7,666 participants, although this number decreased to 5,246 in Wave 4, with 2,410 dropping out to give a dropout rate of 31.60%. In Wave 6, the participant count further decreased to 4,210, with 1,046 dropouts, giving a dropout rate of 45.70%. Overall, 3,456 participants dropped out, representing a dropout rate of 45.10%. Table 3 illustrates the participant counts before and after applying IPW. The number of participants remained unchanged at 7,666 for wave 2 when weighting was applied. For wave 4, the sample size with weighting was adjusted for 5,256 of the 4,235 participants included in the analysis. In Wave 6, the sample size with weighting was 4,210, and the number of participants included was 2,927. Table 4 shows the sample reduction and distribution of weights due to IPW. The number of participants before weighting was 7,666 in Wave 2, which remained the same after weighting. For Wave 4, the participant count was reduced by 19.40%, with an average weight of 1.10 and a standard deviation of 0.25. In Wave 6, the samples size underwent a 30.50% reduction, with an average weight of 1.05 and a standard deviation of 0.30. The weights reflect the impact of truncation on sample weights, showing changes in the distribution and mean weights with the application of IPW.

Table 5 summarizes the RR for respiratory function measures, specifically FEV and FVC, according to the intensity of continuous PA. No PA and two levels of activity intensity levels (moderate and hard) were compared.

Engaging in middle- and hard-intensity exercises was not significantly associated with a lower risk of declining FEV when compared with no exercise (RR = −0.69 and −1.07, 95% CI: −1.48 1.01 and −1.88–0.27, respectively; p = 0.10).

For FVC, engaging in middle-intensity exercise was not significantly associated with a higher risk for declined FVC compared with no exercise (RR = 2.65, 95% CI; −0.16–5.46; p = 0.08). Conversely, engaging in hard-intensity exercise was significantly associated with a higher risk for declined FVC compared with no exercise (RR = 4.10, 95% CI; 1.24–6.95; p < 0.01).

Regarding binary outcomes for FEV, engaging in middle- and hard intensity exercises were significantly associated with a higher risk for declined FEV compared with no exercise (RR = 1.18 and 1.27, 95% CI; 0.92–1.44 and 1.01–1.53, respectively; p = 0.21 and 0.07).

For binary outcomes of FVC, engaging in middle-intensity exercise was not significantly associated with a lower risk of FVC decline than no exercise (RR = 0.95, 95% CI; −0.52–1.37; p = 0.74). Conversely, engaging in hard-intensity exercise was significantly associated with a lower risk of FVC decline than no exercise (RR = 0.63, 95% CI; -0.17–1.09; p = 0.04).

Discussion

This study showed that continued exercise in older adults may maintain respiratory function and was significantly associated with the onset of respiratory diseases. First, engaging in vigorous exercise for >4 years reduced the risk of FVC by 4.10-fold compared with that with no exercise. For restrictive ventilatory disorders, vigorous exercise reduced the risk of FVC by 0.63-fold more than that of no exercise. While the effect of moderate exercise was not significantly different, the FVC analysis showed a p-value slightly outside the 95% CI (p = 0.08), indicating a potential 2.65-fold reduction in FVC. Further studies with larger sample sizes and more refined sampling conditions may identify significant results.

FVC is affected by the mobility of the expiratory muscles and the thorax and decreases with age [25,26]. These findings have important implications for cough management. FVC affects coughing, a crucial defense mechanism for clearing the airway [27]. Decreased expiratory muscle strength and chest wall mobility may impair cough function and increase the risk of aspiration pneumonia. Restrictive ventilatory disorders, although potentially caused by collagen diseases, highlight the importance of maintaining or improving expiratory muscle and chest wall compliance.

Conversely, for FEV, the impact of exercise intensity could not be sufficiently demonstrated over a four-year period. Although the significance of the effect on obstructive ventilation impairment was slightly outside the 95% CI, the estimated value did not strongly indicate an effective exercise impact. Moderate exercise had a similar result for the prevention of obstructive ventilation impairment, with a p-value slightly outside the 95% CI (p = 0.07), and the continuation of intense exercise was associated with a 1.27-fold increase in the risk of obstructive ventilation impairment. This suggests that obstructive ventilation impairment, characterized by symptoms, such as airway obstruction [28,29], may be exacerbated by excessive exercise, potentially worsening respiratory function in those at risk. However, bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome is associated with decreased FEV1 and increased mortality [10]. Additionally, the FEV1/FVC ratio is a strong predictor of mortality in the general population, particularly in patients with COPD [30-33]. Effective preventive measures against obstructive ventilatory impairment include smoking cessation and nutritional management [34]. For COPD, a representative disease of obstructive ventilation impairment, standard treatments and rehabilitation typically involve pulmonary rehabilitation programs that include respiratory therapy, educational programs, psychological counseling, and general exercise [35,36]. In addition, specialized therapies can improve lung function [37]. Therefore, incorporating targeted exercise and patient education is essential, rather than simply engaging in exercise alone.

A notable challenge in this study was the high dropout rate, which was substantial throughout the study period. Specifically, the dropout rates were 31.60% and 45.70% for Waves 4 and 6, respectively, giving an overall dropout rate of 45.10%. This high dropout rate is a critical factor that needs to be addressed as this may influence the robustness of the results. IPW was used to mitigate follow-up bias, which was adjusted for participant loss. The applied weights (Tables 3 and 4) reflect the impact of participant dropouts and ensure that the analysis is representative of the initial sample. Despite these methodological adjustments, the high dropout rate is a limitation of this study. Future research should develop strategies to minimize dropout rates and enhance the reliability and generalizability of the findings.

Respiratory function is closely related to QOL [38]. Additionally, declined respiratory function leads to reduced PA, which significantly diminishes activities of daily living and health-related QOL [39,40]. Respiratory rehabilitation is effective in alleviating breathlessness, increasing exercise tolerance, and improving QOL [41-43]. Furthermore, respiratory training can improve respiratory function, swallowing function, and QOL [44]. However, reduced respiratory function should be prevented using daily preventive measures. These study results, which demonstrate the impact of continuous exercise on respiratory function, are considered to contribute to maintaining or improving the QOL and extending healthy life expectancy.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the reliance on self reported PA levels may introduce reporting bias [42]. Additionally, the exclusion criteria for respiratory function parameters may limit generalizability. Future studies should incorporate more objective measures of PA, such as wearable activity trackers, and consider additional respiratory function metrics.

Conclusion

Overall, this longitudinal study, using data from the ELSA cohort, demonstrated the positive impact of vigorous PA on the maintenance of respiratory function in older adults. The high dropout rate, which reached 45.10% in the final wave, underscores the need for future studies to effectively address participant retention. Continued vigorous exercise over four years significantly reduced the risk of decreased FVC and restrictive ventilatory disorders, contributing to improved respiratory health and potentially extending a healthy lifespan. These findings emphasize the importance of promoting regular PA among older adults as a preventive measure against respiratory function decline and highlight the need for strategies to enhance participant engagement and retention in longitudinal research.

Conflict of Interest:

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations:

VC, vital capacity; FEV, forced expiratory volume; FVC, forced vital capacity; %VC, percentage vital capacity; PA, physical activity; QOL, quality of life; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ELSA, English Longitudinal Study of Aging; HSE Health Survey in England; SDR, sequential doubly robust estimator; RR, relative risk; CI, 95% confidence interval; IPW, inverse probability weighting.

References

Lee, S. H., Yim, S. J., & Kim, H. C. (2016). Aging of the respiratory system. Kosin Medical Journal, 31, 11–18.View

Estenne, M., Yernault, J. C., & De Troyer, A. (1985). Rib cage and diaphragm-abdomen compliance in humans: Effects of age and posture. Journal of Applied Physiology (1985), 59, 1842 1848.View

Tolep, K., & Kelsen, S. G. (1993). Effect of aging on respiratory skeletal muscles. Clinics in Chest Medicine, 14(3), 363–377.View

Pistelli, R., Lange, P., Miller, D. L. (2003). Determinants of prognosis of COPD in the elderly: mucus hypersecretion, infections, cardiovascular comorbidity. European Respiratory Journal Supplements, 40, 10s–14s.View

Gross, R. D., Atwood, C. W., Ross, S. B., Olszewski, J. W., & Eichhorn, K. A. (2009). The coordination of breathing and swallowing in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 179, 559 565.View

Kaneko, H., Suzuki, A., & Horie, J. (2019). Relationship of cough strength to respiratory function, physical performance, and physical activity in older adults. Respiratory Care, 64(7), 828–834.View

Kamikawa, N., Hamada, H., Sekikawa, K., Sekikawa, K., Yamamoto, H., Fujika, Y., …, & Otoyama, I. (2018). Posture and firmness changes in a pressure-relieving air mattress affect cough strength in elderly people with dysphagia. PLOS ONE, 13(12), e0208895.View

Mehrotra, P. K., Varma, N., Tiwari, S., & Kumar, P. (1998). Pulmonary functions in Indian sportsmen playing different sports. Indian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology, 42(3), 412–416.View

Wu, X., Gao, S., & Lian, Y. (2020). Effects of continuous aerobic exercise on lung function and quality of life with asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Thoracic Disease, 12, 4781–4795.View

Cheng, Y. J., Macera, C. A., Addy, C. L., Sy, F. S., Wieland, D., & Blair, S. N. (2003). Effects of physical activity on exercise tests and respiratory function. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 37(6), 521–528.View

Kemp, R., Pustulka, I., Boerner, G., Smela, B., Hofstetter, E., Sabeva, Y., & François, C. (2021). Relationship between FEV(1) decline and mortality in patients with bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome-a systematic literature review. Respiratory Medicine, 188, 106608.View

Monteiro, L., Souza-Machado, A., Valderramas, S., & Melo, A. (2012). The effect of levodopa on pulmonary function in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Therapeutics, 34, 1049–1055.View

Ferreira, G. D., Costa, A. C. C., Plentz, R. D. M., Coronel, C. C., & Sbruzzi, G. (2016). Respiratory training improved ventilatory function and respiratory muscle strength in patients with multiple sclerosis and lateral amyotrophic sclerosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Physiotherapy, 102, 221–228.View

Steptoe, A., Breeze, E., Banks, J., & Nazroo, J. (2013). Cohort profile: The English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. International Journal of Epidemiology, 42(6), 1640–1648.View

American Thoracic Society. (1995). Standardization of spirometry, 1994 update. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 152(3), 1107–1136.View

European Respiratory Society. (2005). Task force on the standardization of lung function testing. European Respiratory Journal, 26(6), 1069–1080.View

Miller, M. R., Hankinson, J., Brusasco, V., Burgos, F., Casaburi, R., Coates, A., & Crapo, R. (2005). Standardisation of spirometry. European Respiratory Journal, 26(2), 319–338.View

Joint Health Surveys Unit, National Centre for Social Research, & University College London Research Department of Epidemiology and Public Health. (2007). The Health Survey for England Physical Activity Validation Study: Substantive Report. Leeds, UK.View

Ikeda, T., Cooray, U., Murakami, M., & Osaka, K. (2022). Maintaining moderate or vigorous exercise reduces the risk of low back pain at 4 years of follow-up: Evidence from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Journal of Pain, 23(3), 390–397.View

Schuler, M. S., & Rose, S. (2017). Targeted maximum likelihood estimation for causal inference in observational studies. American Journal of Epidemiology, 185(1), 65–73.View

Polley, E., LeDell, E., Kennedy, C., Lendle, S., & van der Laan, M. (2024). SuperLearner: Super learner prediction. Retrieved July 15, from https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ SuperLearner/SuperLearner.pdfView

Friedman, J. H. (1991). Multivariate adaptive regression splines. The Annals of Statistics, 19(1), 1–141. https://doi.org/10.1214/ aos/1176347963View

Wright, M. N., & Ziegler, A. (2017). ranger: A fast implementation of random forests for high dimensional data in C++ and R. Journal of Statistical Software, 77(1), 1–17.View

Chen, T., & Guestrin, C. (2016). XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (pp. 785–794).View

Kaneko, H., & Suzuki, A. (2017). Effect of chest and abdominal wall mobility and respiratory muscle strength on forced vital capacity in older adults. Respiratory Physiology & Neurobiology, 246, 47–52.View

Smith, J. A., Aliverti, A., Quaranta, M., McGuinness, K., Kelsall, A., Earis, J., & Calverley, P. M. (2012). Chest wall dynamics during voluntary and induced cough in healthy volunteers. Journal of Physiology, 590(3), 563–574.View

McCool, F. D. (2006). Global physiology and pathophysiology of cough: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest, 129(1 Suppl), 48S–53S.View

Nakamura, Y., Tamaoki, J., Nagase, H., Yamaguchi, M., Horiguchi, T., Hozawa, S., Ichinose, M., …, Tohda, Y., The Japanese Society of Allergology. (2020). Japanese guidelines for adult asthma 2020. Allergology International, 69, 519–548.View

Bidan, C. M., Veldsink, A. C., Meurs, H., & Gosens, R. (2015). Airway and extracellular matrix mechanics in COPD. Frontiers in Physiology, 6, 346.View

Miller, M. R., & Pedersen, O. F. (2010). New concepts for expressing forced expiratory volume in 1 s arising from survival analysis. European Respiratory Journal, 35(4), 873–882.View

Bhatta, L., Leivseth, L., Mai, X.-M., Henriksen, A. H., Carslake, D., Chen, Y. ,.., & Brumpton, B. M. (2021). Spirometric classifications of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease severity as predictive markers for clinical outcomes: The HUNT Study. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 203(8), 1033–1037.View

Costanzo, S., Magnacca, S., Bonaccio, M., Di Castelnuovo, A., Piraino, A., Cerletti, C., ..., & Iacoviello, L. (2021). Reduced pulmonary function, low-grade inflammation and increased risk of total and cardiovascular mortality in a general adult population: Prospective results from the Moli-sani study. Respiratory Medicine, 184, 106441.View

Hegendörfer, E., Vaes, B., Andreeva, E., Matheï, C., Van Pottelbergh, G., & Degryse, J.-M. (2017). Predictive value of different expressions of forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) for adverse outcomes in a cohort of adults aged 80 and older. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 18(2), 123–130.View

Holtjer, J. C. S., Bloemsma, L. D., Beijers, R., Cornelissen, M. E. B., Hilvering, B., Houweling, L., ..., Maitland-Van der Zee, A. H., P4O2 consortium. (2023). Identifying risk factors for COPD and adult-onset asthma: An umbrella review. European Respiratory Review, 32, 230009.View

Ries, A. L., Bauldoff, G. S., Carlin, B. W., Casaburi, R., Emery, C. F., Mahler, D. A., ..., & Herrerias, C. (2007). Pulmonary rehabilitation: Joint ACCP/AACVPR evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest, 131(5, Suppl), 4S–42S.View

Mikelsons, C. (2008). The role of physiotherapy in the management of COPD. Respiratory Medicine COPD Update, 4(1), 2–7.View

Leelarungrayub, J., Puntumetakul, R., Sriboonreung, T., Pothasak, Y., & Klaphajone, J. (2018). Preliminary study: Comparative effects of lung volume therapy between slow and fast deep-breathing techniques on pulmonary function, respiratory muscle strength, oxidative stress, cytokines, 6-minute walking distance, and quality of life in persons with COPD. International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, 13, 3909–3921.View

Xie, G., Li, Y., Shi, P., Zhou, B., Zhang, P., & Wu, Y. (2005). Baseline pulmonary function and quality of life 9 years later in a middle-aged Chinese population. Chest, 128(4), 2448–2457.

Pitta, F., Troosters, T., Probst, V. S., Spruit, M. A., Decramer, M., & Gosselink, R. (2006). Physical activity and hospitalization for exacerbation of COPD. Chest, 129, 536–544.View

Carr, S. J., Goldstein, R. S., & Brooks, D. (2007). Acute exacerbations of COPD in subjects completing pulmonary rehabilitation. Chest, 132, 127–134.View

Goldstein, R. S., Gort, E. H., Avendano, M. A., Stubbing, D., & Guyatt, G. H. (1994). Randomised controlled trial of respiratory rehabilitation. Lancet, 344(8934), 1394–1397.View

Ries, A. L., Kaplan, R. M., Limberg, T. M., & Prewitt, L. M. (1995). Effects of pulmonary rehabilitation on physiologic and psychosocial outcomes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Annals of Internal Medicine, 122(11), 823 832.View

Wijkstra, P. J., van der Mark, T. W., Kraan, J., van Altena, R., Koëter, G. H., Postma, D. S. (1996). Effects of home rehabilitation on physical performance in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). European Respiratory Journal, 9(1), 104–110.View

Maki, N., Takahashi, H., Nakata, T., Wakayama, S., Hasegawa, D., Sakamoto, H., ..., Yanagi, H. (2016). The effect of respiratory rehabilitation for the frail elderly: A pilot study. Journal of General and Family Medicine, 17(4), 1–10.View

Troiano, R. P., Berrigan, D., Dodd, K. W., Mâsse, L. C., Tilert, T., & McDowell, M. (2008). Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 40(1), 181–188.View