Journal of Comprehensive Nursing Research and Care Volume 10 (2025), Article ID: JCNRC-208

https://doi.org/10.33790/jcnrc1100208Research Article

Factors Related to Personal Resilience Scale of Local Residents: Experiences of Long-term Evacuation from Natural Disasters

Manami Yasuda*

Professor, Department of Nursing, Faculty of Global Nursing, University of Iryo Sosei, Chiba, Japan.

Corresponding Author Details: Manami Yasuda, Professor, Department of Nursing, Faculty of Global Nursing, University of Iryo Sosei, Chiba, Japan.

Received date: 15th November, 2024

Accepted date: 10th January, 2025

Published date: 13th January, 2025

Citation: Yasuda, M., (2025). Factors Related to Personal Resilience Scale of Local Residents: Experiences of Long-term Evacuation from Natural Disasters. J Comp Nurs Res Care 10(1): 208.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Abstract

The objective of this study was to examine the factors associated with personal resilience to natural disasters and to identify strategies for providing support in local communities. A self-administered questionnaire was administered to residents who were still living as long-term evacuees eight years after the Great East Japan Earthquake. The questionnaire includes items assessing personal resilience. A total of 201 valid responses were subjected to analysis. The results of multiple regression analysis indicated that the Sence of Coherence (β = 0.422), Mental Resilience (β = 0.331), Mental Health K6 (β = -0.185), and Community Acceptance (β = 0.124) were significantly associated with the personal resilience to natural disasters PRS scale scores. The findings indicated that enhancing resilience to natural disasters necessitates a dual approach, encompassing both practical measures that impart tangible knowledge and information to assist individuals in navigating the multifaceted stressors associated with disasters, and emotional coping strategies that demonstrate empathy for their challenging experiences.

Keywords: Resilience, Related Factors, Sence of Coherence, natural Disaster, Residents, Japan

Introduction

In the context of reconstruction assistance for victims of natural disasters who have been displaced from their homes and compelled to reside in evacuation centers, there has been a notable surge in recent years in both the urgency to expedite the redevelopment of living infrastructure and the imperative to assist these individuals in navigating the emotional challenges associated with the significant shifts in their lives. The concept of resilience is being emphasized as an ability to overcome difficulties caused by adversity. Individual resilience can be defined as a phenomenon or process that reflects a relatively positive adjustment despite significant adversity or trauma [1]. It is the capacity to deploy and utilize one's intrinsic capabilities to reestablish mental well-being and adapt to life in a wake of a disaster. Support provided to individuals during a disaster is not solely limited to physical improvements, such as food aid and building repairs. It also encompasses emotional support for those experiencing significant stress due to the post-disaster changes.

There is a positive correlation between resilience and mental health, including psychological adjustment and self-esteem [2-4]. Furthermore, resilience has been demonstrated to serve as a protective factor against negative mental health conditions such as stress, anxiety, and depression [5-7]. The measurement of resilience related factors in a planned manner has been challenging due to the inherent unpredictability of disasters.

Consequently, although the significance of providing supports and fostering resilience among community members during disasters has been acknowledged, there is a dearth of research examining resilience-related factors among community members during disasters. This study examined factors related to resilience for disaster victims using the [Personal Resilience Scale in Natural Disasters], and discussed the provision of community-based support.

Methods

Survey Period

The survey was conducted between August and September of 2019, eight years after the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake.

Survey Targets and Data Collection Methods

The target population comprised individuals who possessed a certificate of residence within the geographical area impacted by the Great East Japan Earthquake. The Great East Japan Earthquake they encountered was a magnitude 9.0 earthquake and a natural disaster that triggered a massive tsunami [8]. It is possible that disaster victims may exhibit vulnerability to stress when prompted to discuss details related to the disaster. In light of these considerations, the purpose of the survey and ethical implications were elucidated for the health center personnel in the affected regions prior to the survey’s implementation, and their collaboration was secured. As a preliminary measure, the aforementioned personal provided an overview of the survey to the residents and extended an invitation for their participation subsequent to the conclusion of the health assessments. The invitation was crafted with great care to avoid causing distress to the residents. Subsequently, a request letter and questionnaire delineating scribing the objectives of the study and ethical considerations were distributed to the 371 residents who had expressed interest in participating in the survey. In principle, the questionnaire was completed anonymously. However, respondents who were not inclined to utilize this methodology due to their advanced age were instead interviewed by the researcher. The estimated time required to answer the questions was approximately 10 minutes.

Methods and Criteria

A self-administered questionnaire survey was conducted in order to obtain data for analysis. The questionnaire comprised 16 items designed to assess the Personal Resilience Scale (PRS: provisional version) of which was used in this study, in relation to natural disasters [9,10]. Additionally, the questionnaire incorporated a number of scales pertaining to resilience. These included the Mental Health K6, the University of Tokyo SOC3 Item Scale for Health and Sociology (SOC3-UTHS), and the Adolescent Resilience Scale (ARS).

The Personal Resilience Scale to Natural Disasters (PRS) is a 16- item, 4-subscale instrument currently under development by the author. The scale has been demonstrated to possess a certain degree of reliability and validity [10]. Responses were rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 to 4, with the following answer of “not at all applicable”, “somewhat applicable”, “neither applicable nor not applicable”, “somewhat applicable,” and “very applicable”. The scores ranged from 0 to 156. Higher scores are indicative of greater resilience.

The Japanese version of the K6 questionnaire, which was developed to screen for mood and anxiety disorders, was utilized in this study [11]. The items were posed on a 5-point scale, with a cutoff score of 13 or higher indicative of a severe mental disorder. Higher scores are indicative of poorer mental health.

The SOC3-UTHS is a measure of the Sense of Coherence (SOC), which reflects the 3 sub-concepts of the SOC, namely “manageability”, “meaningfulness”, and “comprehensibility”. The scale comprises three items, each of which is rated on a seven point Likert scale. The reliability and validity of the scale have been demonstrated by Togari et al [12]. Higher scores indicate a higher level of SOC. Permission has been obtained for the use of this scale.

The ARS is a quantitative measure of mental resilience that facilitates recovery from mental depression [13]. The scale is comprised of 3 subscales: “novelty seeking,” “emotional regulation,” and “positive future orientation.” The scale comprises 21-item, presented on a 5-point Likert scale, and has been subjected to rigorous testing to ensure its reliability and validity. The necessary permission to utilize the scale were obtained.

An item was constructed to assess the level of acceptance (accepted, rather accepted, rather unaccepted, and not accepted) within the community in which the individual currently resides.

The following personal attributes were considered: gender, age (20-39/40-59/60-79), presence of family members living with them, current place of residence (municipality where they lived before the disaster/relocated within the prefecture after the disaster/relocated outside the prefecture after the disaster), and housing type (owner-occupied/temporary housing).

Analysis

For statistical processing, the basic statistical calculations for individual attributes were performed using the SPSS Statistics software, version 28.0.

To confirm the reliability of the Personal Resilience to Natural Disasters (PRS) scale, Cronbach's alpha coefficients were calculated for the total score and subscale scores of the PRS scale. The PRS, the total mental health (K6) score, the SOC3-UTHS score for health generating capacity, the mental resilience (ARS) score, which promotes recovery from mental depression, and the score of the current level of acceptance from the local population are presented with means ± standard deviation for the five scales.

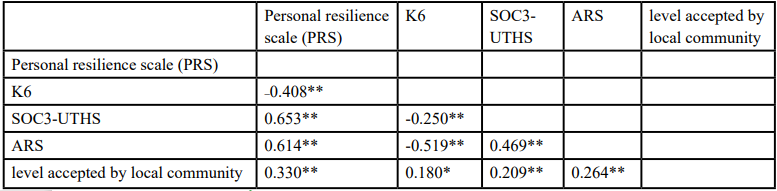

Correlation coefficients were calculated between the five measures of personal resilience to natural disasters (PRS), K6, SOC3-UTHS, ARS, and the current level of acceptance by the community. To analyze differences in personal resilience to natural disasters (PRS) by individual attributes, two-group comparisons were conducted using t-tests, while three -group comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA.

A multiple regression analysis was conducted using the stepwise method, with personal resilience to natural disasters (PRS) as the dependent variable and variables that demonstrated significant differences in the statistical analysis as independent variables. In all tests, a significance level of P < 0.05 was employed.

Ethical Considerations

The study was subjected to a rigorous ethical review by the research ethics committee of my university. The cover page of the questionnaire form included a description of the ethical considerations associated with the study, including the purpose and objectives, the voluntary nature of participation, the protection of privacy, and the strict control and processing of data. These considerations were also verbally explained to participants as needed. The act of consenting to participate in the study was considered to have been completed when the consent form section was duly completed, and the questionnaire was submitted.

Results

Collection status and persons analyzed

A total of 371 individuals were invited to participate in the survey, and 212 completed questionnaires were received. Following the exclusion of respondents with a high number of errors or missing information, a total of 201 valid responses (representing a valid response rate of 54.2%) were included in the subsequent analysis.

Basic attributes of the subjects

The initial step is to present the percentage of individuals who selected each response option for the target variable (see Table 1). The majority of respondents (61.1%) were between the age of 60 and 79, and 57.2% were female. The majority of respondents (80.6%) indicated that they currently have family members residing with them. The majority of respondents (94%) were residing in other municipalities within the same prefecture following the earthquake, while only 3.0% were residing in their original homes prior to the earthquake.

Reliability of the Personal Resilience to Natural Disasters (PRS) Scale

The reliability coefficient, Cronbach's alpha, for the Personal Resilience to Natural Disasters (PRS) scale was 0.92. The Cronbach's alpha for each subfactor was 0.89 for the first factor, Social Support, 0.84 for the second factor, Positive Thinking, 0.88 for the third factor, Stress Coping, and 0.88 for the fourth factor, Problem Solving Ability. The scale was found to be highly reliable.

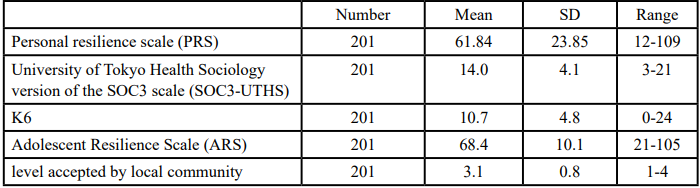

Mean and standard deviation of personal resilience to natural disasters (PRS), K6, SOC3-UTHS, ARS, and current level of community acceptance

The means and standard deviations for the five measures of personal resilience to natural disasters (PRS), K6, SOC3-UTHS, ARS, and the current level of community acceptance are presented in Table 2 for purposes of analysis.

Factors associated with personal resilience scale to natural disasters (PRS)

The results of the correlation coefficients, which demonstrate the relationship between the Personal Resilience Scale to Natural Disasters (PRS) and other variables, are presented in Table 3. Significant correlations were identified between the five scales.

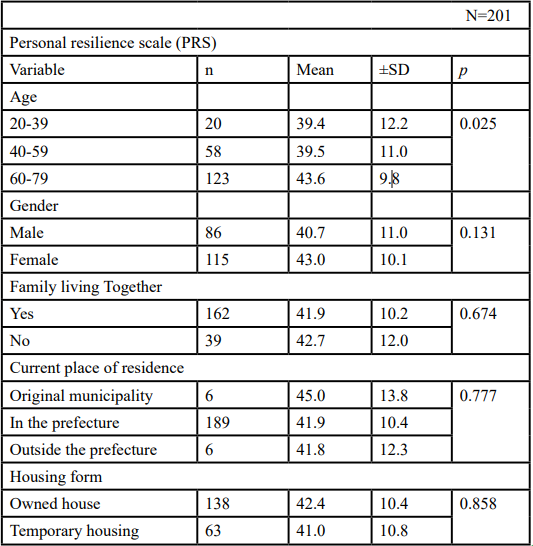

The results of the PRS differences by personal attributes are presented in Table 4. No items demonstrated statistically significant differences in PRS scores based on personal attributes.

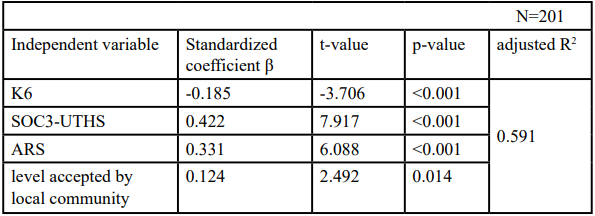

A multiple regression analysis was conducted using the four items that were significantly associated with PRS scores, K6, SOC3-UTHS, ARS, and current level of community acceptance as independent variables and PRS as the dependent variable (Table 5). The adjusted coefficient of determination (R2) for the regression equation was 0.591, indicating that the model was significant with a P-value of less than 0.1%. The item that had the greatest impact on PRS scores was SOC3-UTHS (β = 0.422). The variance inflation factor (VIF) for this analysis ranged from 1.10 to 1.34. Accordingly, the variables in question are not deemed to be multicollinear.

Table 3. Pearson’s correlation coefficient between PRS, K6, SOC3-UTHS, ARS, and level accepted by local community

Discussion

In this study, nearly half of the subjects were aged 60 years or older. As a percentage of the total Japanese population aged 65 and over, the aging rate is 28.6% [14]. The aging rate in the area where the subjects lived in the year before the earthquake was 24.8% [15]. Compared to these figures, it was hypothesized that the outflow of the younger generation for economic activities in disaster-affected areas the has contributed to the aging of the population. Furthermore, over 60% of respondents relocated their residences and rebuilt their homes following the disaster, as they continued to reside in long-term evacuation shelters. Stabilizing their living infrastructure in their new places of residence is considered an immediate issue. Prior research has indicated that stress and feeling of alienation in these new living environments can lead to a decline in mental health and well-being [16,17]. It is therefore imperative that further investigation be conducted into the resilience of disaster victims who are facing a multitude of challenges in the aftermath of such disasters.

The results of the multiple regression analysis indicated that the sense of coherence (SOC) had the greatest impact on resilience to natural disasters. The three components of SOC, namely comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness, are regarded as factors that enhance adaptive capacity when encountering difficulties. In other words, when an individual is able to comprehend the circumstances and their own position when confronted with adversity (sense of grasping), they are better equipped to envisage a future trajectory and to respond in a composed manner. Those who have developed a sense of being able to cope with challenging circumstances (sense of processability) are more likely to believe that they will be able to overcome these situations in the future. This belief may contribute to a sense of confidence and resilience, reducing the likelihood of feeling overwhelmed or trapped. It has been documented that those individuals with high SOC demonstrate enhanced stress coping abilities. Therefore, potential avenues for bolstering SOC and fostering resilience in the face of adversity can be delineated as follows. In other words, it is recommended that information and knowledge be provided in a realistic and concreate manner so that survivors can gain an accurate understanding of their situation and develop a broader perspective when affected by the disaster. Subsequently, it is recommended that emotional coping strategies be provided, which can be shared in an emotional manner, so that survivors feel they can make it through the difficulties. Subsequently, the provision of diverse insights and experiences is recommended to facilitate the meaningful navigation of challenges.

Conclusion

In order to enhance resilience to natural disasters, it is essential to furnish individuals with the requisite knowledge and information to enable them to cope with the multifaceted stresses associated with such events and to facilitate their ability to gain perspective. Concurrently, it is proposed that a dual approach to support is required, with an emphasis on emotional coping strategies that demonstrate empathy for challenging experiences.

Conflict of Interest:

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Author Contributions:

The author contributed to the conception of the study and the overall study process.

Acknowledgments:

The author would like to thank all the participants for their cooperation in this study.

Funding:

This study has not received any funding.

References

Sasaki, Y., Aida, J., Tsuji, T., Koyama, S., Tsuboya. T, et al (2019). Pre-disaster social support is protective for onset of post-disaster depression: Prospective study from the Great East Japan Earthquake & Tsunami. Scientific Reports 9: e19427. View

Connor, K.M., & Davidson, J.T. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CDRISC). Depress Anxiety 18: 76-82. View

Hirano, M. (2012). An examination of the buffering effect of resilience on psychological sensitivity: Can we compensate for our original "weakness" from an acquired perspective? Japanese J. Educ. Psychol 60: 343-354.

Koshio, S., Nakatani, M., Kaneko, K., & Nagamine, S. (2002). Psychological characteristics that lead to recovery from negative events: Creation of a mental resilience scale. Counseling Research 35: 57-65.

Rutter, M. (1985). Resilience in the face of adversity: Protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorder. British J of Psychiatry 147: 598–611.View

Bonanno, G.A. (2004). Loss, trauma and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? American Psychologist 59:20–28. View

Fletcher, D., Sarkar, M. (2013). A Review of Psychological Resilience; a review and critique of definitions, concepts, and theory. European Psychologist 18:12-23.View

Cabinet Office, Government of Japan (2025). Overview of the Great East Japan Earthquake, Special Feature: The Great East Japan Earthquakeetrieved from https://www.bousai.go.jp/ kohou/kouhoubousai/h23/63/special_01.htmlView

Yasuda, M., Nitta, M. (2020). A Study on Conceptual Structure of Mental Health Resilience in Disasters and Creation of a Scale. Abstracts of the 27th Annual Meeting of the Japanese Society of Behavioral Medicine(suppl), 56.

Yasuda, M. (2023). Development of the "Personal Resilience Scale (PRS)" for Natural Disasters. Int J Nurs Clin Pract 10: 382.View

Furukawa, T.A., Kawakami, N., & Saito, M. (2008). “The performance of the Japanese version of the K6 and K10 in the World Mental Health Survey Japan,” International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research,17(3), 152-158.View

Togari, T. (2008). Development of the University of Tokyo Health Sociology version of the SOC3 scale (SOC3-UTHS) for a large-scale multi-purpose general population survey. Discussion Paper Series 4, Institute of Social Science, Tokyo University Press, JAPAN. View

American Psychological Association (APA) (2023). Building Your Resilience retrieved from https://www.apa.org/topics/ resilience/building-your-resilience. View

cabinet administration office of Japan (2023). Aging of the Population. Defense White Paper 2023 from https://www. bousai.go.jp/kaigirep/hakusho/r05/honbun/t1_2s_03_02.html. View

Fukushima Revitalization Information Portal Site (2025). Trends in Aging Population Rates retrieved from https://www. pref.fukushima.lg.jp/site/portal/jinko-02.html. View

Yokoyama, Y., Otsuka, K., Kawakami, N., Kobayashi, S., Ogawa, A.(2014). Mental Health and Related Factors after the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami. PLoS One 9: e102497.View

Kukihara, H., Uchiyama, K., & Horikawa, E. (2015). Trauma, Depression, resilience of victims of the earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear accident in Japan. J of Neuropsychiatry 117: 957- 964.View