Journal of Comprehensive Nursing Research and Care Volume 10 (2025), Article ID: JCNRC-218

https://doi.org/10.33790/jcnrc1100218Research Article

Faculty as Standardized Patients: An Innovative Approach to Simulation in Nurse Practitioner Education

Sandhya Nadadur1*, DNP, FNP-BC, Theresa Lundy2 PhD, FNP RN, Darlene Dickson3 DNP, CPNP-PC, and Cassandra Dobson4, PhD, RN-BC, PHc

1Assistant Professor and Co-Program Director MS/FNP Program, Department of Nursing, Lehman College, 250 Bedford Park Boulevard West Bronx, NY 10468, United States.

2Assistant Professor, Department of Nursing, Lehman College, 250 Bedford Park Boulevard West Bronx, NY 10468, United States.

3Clinical Professor and Director DNP Program, Department of Nursing, Lehman College, 250 Bedford Park Boulevard West Bronx, NY 10468, United States.

4Associate Professor, Department of Nursing, Lehman College, 250 Bedford Park Boulevard West Bronx, NY 10468, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Sandhya Nadadur, DNP, FNP -BC, AGPCNP-C, Assistant Professor and Co-Program Director MS/ FNP Program, Department of Nursing, Lehman College, 250 Bedford Park Boulevard West Bronx, NY 10468, United States.

#Support was Provided by a PSC-CUNY Research Award from The City University of New York.

Received date: 22nd August, 2025

Accepted date: 26th November, 2025

Published date: 28th November, 2025

Citation: Nadadur, S., Lundy, T., Dickson, D., & Dobson, C., (2025). Faculty as Standardized Patients: An Innovative Approach to Simulation in Nurse Practitioner Education. J Comp Nurs Res Care 10(2):218.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Purpose: The purpose of the study was to evaluate the effectiveness of simulation using faculty standardized patients on perceived confidence in performing competencies among family nurse practitioner students.

Methods: The study design is one group pre-test and posttest design with survey questionnaire. Four simulation sessions were conducted at the Nursing-Simulation lab over four weeks in April 2025. Thirteen family nurse practitioner students who had completed their pediatric rotation and enrolled in the adult clinical course participated. Student participation was not mandated. Three nursing faculty members volunteered to participate in the simulation as standardized patients. Faculty “patients” presented with gastrointestinal complaints and gave verbal clues as students examined the mannequins for the physical exam component. The faculty received details of the scenario, the objectives and a script via email one week before the scenario. The topic of the gastrointestinal system was covered in the class and students were given a quiz prior to implementing the simulation. Each simulation session began with the pre-brief, introduction to the patient via a door note on a lap -top computer, simulation with the faculty patient, and a debrief. There were time outs called by participants and faculty when simulation was suspended for students to collaborate and discuss with peers and observers. Confidence levels of students were measured with a questionnaire before and after the simulation.

Results: The Kirkpatrick model level 2 was used to assess learning. The scores for perceived self- confidence with the simulation intervention showed statistically significant improvement for performing all the 4 nurse practitioner sub-competencies -history taking, performing physical exam, formulating differential diagnoses and planning care.

Conclusion: Simulation using nursing faculty as standardized patients is feasible and could be a cost-effective alternative to enhance student learning.

Keywords: Family Nurse Practitioner, Faculty Standardized Patient, Simulation, Confidence, Kirkpatrick Model

Introduction

“Simulation is a technique that creates a situation or environment to allow persons to experience a representation of a real event for the purpose of practice, learning, evaluation, testing, or gain understanding of systems or human actions” [1]. Simulation is recognized as one of the most innovative teaching tools to teach and assess nurse practitioner (NP) student competencies. This pedagogical tool has been used with proven effectiveness in improving competencies such as diagnostic reasoning, communication and patient management [2-5]. A recent large survey by Nye and colleagues reported that within the US and Canada 98% of the advanced practice nurse (APN) education programs which includes NP education use some modality of simulation [5].

Simulation in NP education provides students with consistent, contextual and quality learning experiences [5]. It mitigates some of the challenges that NP educators have in providing all the learners with quality clinical experience. The challenges include lack of quality clinical sites, scarcity of expert preceptors, preceptors unwilling to precept without financial compensation, and facility workflow interference. These factors impact NP student learning experience at clinical sites. Further, major differences in the work experience of nurses who enroll in the nurse practitioner program also pose challenges in preparing them for the NP role. Simulation addresses these variabilities among learners and complements the clinical experience.

Background

Simulation using OSPs (occupational standardized patients) also referred to as SPs (standardized patients) has been proven to be useful to teach NP students clinical skills and competencies such as taking patient history, performing physical exam, formulating differential diagnoses, planning care and communicating with patients [2-5]. OSPs are individuals who are trained and paid for acting to exhibit specific disease symptoms and give their medical history and provide feedback to students.

A recent systematic review summarized the evidence supporting use of in-person simulation with OSPs in advanced practice nursing education [2]. The review found high student satisfaction and confidence scores, specifically in the areas of health assessments - namely physical exam, history-taking, care-plan development, communication and empathy skills. Most studies reviewed were part of formative assessments and sought student feedback to improve learning.

However, contrary to the benefits, studies in the review also reported poor clinical performance of students in the simulation [2]. This was attributed to inadequate role performance by the OSPs. The feedback from the students noted that OSPs were not well trained to give history and did not give helpful feedback post-simulation. Also, the scenarios were not perceived as authentic because of the OSPs’ poor portrayal of symptoms. The review did not include any study with FSPs (faculty who played the role of standardized patients). However, a study conducted in China reported on the effectiveness of faculty standardized patients (FSPs] used in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) education [6].

Huang and colleagues compared the effectiveness of simulation in a RCT using FSP and OSP with the Traditional Teaching (TT) method. They found no statistical difference in the scores for clinical competence between the FSP and OSP groups [6]. Both groups scored higher in the physical exam, knowledge test, and student satisfaction than the TT group. Higher levels of agreement on the Likert Scale scores were achieved for “professional feedback” in the FSP group than the OSP group. Additionally, the overall cost of training for FSPs was only half that of hiring and training OSPs.

Among APN education programs traditional simulation using standardized patients (SP) is the most used modality- reported as 68% [5]. Considering that it’s the most widely used modality, data from using nursing faculty for the role of SPs (FSP) in fact-to-face or in-person simulation is underexplored and underreported. Using nursing faculty members for the role of standardized patients [FSP] is an innovative approach. It may help nursing programs design and implement simulation utilizing the available resources to improve student learning.

Purpose

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the effectiveness of simulation in which faculty play the role of standardized patients. The research questions are: 1) Is it feasible to use nursing faculty members for the role of patients in simulation 2) What is the effect of simulation using FSPs on the confidence level of students in performing specific NP competencies?

Theoretical Framework

To evaluate students’ learning from the simulation sessions, the Kirkpatrick's Levels of Evaluation Model was used [7]. The model categorizes the evaluation or the effect of the training or educational programs in four ascending levels (1) reaction (2) learning (3) behavior and (4) outcomes [7]. The reaction level evaluates the affective component assessing the likeability and emotional response to the simulation; the learning level evaluates the change in knowledge, skills and attitudes and perceived confidence levels. The level 3 behavior level evaluates the behavior change on the job which is the transfer of the skills learned from the simulation setting to the job, and the fourth level evaluates cumulative and overall outcomes which in the health care field translates to patient outcomes. The model provides flexibility with measuring learning [8]. The tool to measure learning can be tailored to the specific content. The model also does not dictate at what time point learning should be evaluated [8].

The evaluation of learning guided by the Kirkpatrick model has been widely used in education and training programs for undergraduate and graduate nursing students and professional nurses [8-10]. Johnston and colleagues conducted a systematic review to evaluate learning from different debriefing methods following high fidelity simulation [8]. The reviewers noted that evaluation was focused mainly on Kirkpatrick levels of learning 1 and 2. Kirkpatrick level 3 and 4 learning have been studied among practicing nurses in clinical settings [10]. Because level 3 learning evaluates transfer of learned behavior/skills from simulation lab to the practice setting and level 4 learning is reflected in patient outcomes, the evaluation of higher levels of learning in academic settings poses practical challenges [8]. Hence this study evaluates the effectiveness of simulation using FSPs on learner satisfaction which is the level 1 -reaction and change in confidence levels in performing NP competencies from pre-simulation to post-simulation which is level 2 of the Kirkpatrick Model.

Methodology

Study Design: This is a pre-test and post-test study design with a survey questionnaire. The Institutional Review Board approval for the study was obtained from the university, approval -CUNY-UI IRB 2025-0102. The study was conducted in a government funded public college in the Northeastern United States. Written consents were obtained from nursing faculty and family nurse practitioner (FNP) students before each pre-brief session of the simulation. A total of 13 students were divided into four groups of two to four participants. Each group was assigned to a different scenario related to the gastrointestinal system. Each week one simulation session was conducted. Each session lasted for about 45 minutes to 1 hour. The simulations were conducted, and data was collected in March and April 2025.

Recruitment: A flyer was sent to faculty during the faculty meeting to sign up to play the role of a faculty standardized patient in the simulation. Faculty volunteered or self-selected to play the role of standardized patient. Those faculty who signed up for the role of SP were then notified of the date and time when they needed to be present in -person in the simulation lab. The faculty researcher taught the clinical course. Announcements were made on the learning platform about the simulation to recruit students. In addition, announcements were also made in class to recruit interested students. Participating in the simulation and observing were not mandatory. There were no grades attached to the learning experience. Students who verbally expressed interest in participating were required to come in one hour before the scheduled class.

Preparation of students: There are 3 clinical courses in the FNP curriculum. Students in our program start with pediatric and then progress through adult and then geriatrics courses. The FNP students in this study had completed their pediatric clinical hours and were at different points of completing their adult clinical hours. The didactic lecture content on the gastrointestinal system which was the only system included in the simulation was covered in the class 2 weeks before the start of the simulation. Students were also given a quiz which covered the gastrointestinal system before implementing the simulation sessions. The simulation was planned to achieve the course objectives- Synthesize knowledge of basic sciences and pathophysiology as a foundation for clinical management of adults and their communities, demonstrate critical thinking and diagnostic reasoning skills in clinical decision making, manage acute and chronic illness within the scope of nurse practitioner knowledge, and provide comprehensive and individualized primary care to the adult patient. These objectives are also aligned with the required quality standards for nurse practitioner education put forth by the National Task Force on Quality Nurse Practitioner Education [11].

Sample characteristics: The sample included 13 FNP students- 2 male and 11 females. Their current role included direct patient care 92% and administration 8%. The settings for direct patient care included emergency room- 8%, medical surgical inpatient - 84%, and outpatient clinic-8%. The years of experience as a registered nurse- 23% reported under 5 years of experience, 38% reported 6-10 years of experience, 8% with 11-15 years, 8% with 21-25 years, and 23% with 26-30years of experience.

Role of faculty: Faculty participants were given scripts a week before the simulation which included a chief complaint, social and family history, past medical and surgical history and daily medications. The scripts were developed in consultation with content experts- NPs practicing in gastrointestinal subspecialty. The faculty were given the opportunity to have any questions answered by the researcher before the simulation scenario unfolded. In addition to giving history and presenting signs and symptoms, faculty “patients” (FSP) also gave verbal clues as the students performed examination on the mannequin that took the place of faculty for the physical exam. They also provided brief feedback to students after each simulation. They filled out an optional survey after the simulation.

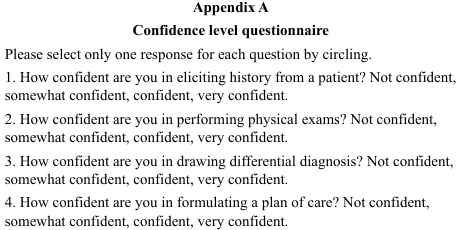

Survey questionnaire: The students were required to rate their perceived confidence in performing select NP competencies. A Likert type confidence questionnaire in appendix A was administered immediately before and after the simulation. The survey questionnaire was self-prepared. It was not pretested. The 4 items on the tool are aligned with the targeted objectives and the competencies to be achieved with simulation scenarios. It required students to circle the Likert type response. The confidence level rating from the lowest to the highest ranged from one to four and scored as not confident = 1, somewhat confident =2, confident =3 and very confident=4. The responses to all the 4 items in the survey questionnaire for both pre- and post-tests were input in the SPSS to obtain reliability statistics. The reliability calculated as Cronbach Alpha .75.

Procedure: After obtaining the consents, the confidence level survey questionnaire was administered for the student participants. Then the students were given pre-brief. The pre-brief oriented the students to the setting-primary care outpatient setting, time limitations, respectful and professional communication, confidentiality, the use of time outs for consulting with participants, peers and faculty researcher, simulation objectives and student expectations. The objectives of the simulation were a) Take a history of an adult patient presenting with abdominal pain with focus on pertinent positive and negative symptoms b) Perform focused physical exam for a patient with abdominal pain c) Formulate a broad set of differential diagnosis based on history, physical exam and diagnostic test results. d) Develop and communicate the plan of care in collaboration with the patient [12].

First, the students reviewed the door note which provided the past medical and surgical history and current medications and most recent lab results from the laptop. They assigned among themselves different parts of the patient visit/encounter. They then introduced themselves to the faculty patient (FSP) and obtained a detailed history of the presenting complaint, did a review of systems when examining the mannequin at which time they also received simultaneous verbal clues from the faculty patient (FSP), they collaborated and developed a broad list of differential diagnosis. The students then ruled in and ruled out some of the diagnoses by asking the faculty patient focused questions. They then developed a working list of diagnoses. Next, the students collaborated and reviewed the results of previous diagnostic tests and proceeded to order further testing and developed a plan of care. They communicated the plan of care to the faculty patient which included – likely diagnosis, need for the tests, monitoring for worsening symptoms, and potential side-effects of the medications. Self-care was also discussed, for example diet, activity, and work; included were also the need for follow-up, and when to seek emergency care. Students called a time out to consult with their participating peers and the faculty when needed. Faculty also called time out to facilitate the progression of the simulation and to give prompts to the students. During timeouts the scenario was suspended, and the faculty patient did not participate.

Debriefing was done by the faculty researcher for all the 4 scenarios. The emphasis on context was reinforced in the debriefing [13]. All the participating students filled out the post-intervention survey on confidence levels.

Feasibility: Documentation of components of feasibility which included study expenses, coordination with and cooperation of faculty, staff and students, and timeline for the completion of the study were maintained. Documentation of time spent on coordinating the simulation among the lab technician and faculty, arranging for the lab schedule and the cost of conducting the simulation were calculated.

Data Analysis

The pre- and post-simulation confidence levels for history taking, performing physical exam, formulating differential diagnoses and planning of care were tabulated in 8 columns using Excel. The medians scores for each of the columns were obtained. Analysis of the pre-and post-simulation confidence levels across all the 4 NP sub-competencies were conducted with the SPSS using the non parametric test -Wilcoxon Signed Rank test.

Results

All the 24 students who attended the simulation either as a participant or an observer expressed their satisfaction with the simulation activity and their desire for simulation to be included as part of the scheduled class. This data was extracted from the responses from the end of the semester evaluation of the teaching and learning to question- “what aspects of the class contributed to your learning”. This is reflective of the level 1 Kirkpatrick learning.

Results showed a statistically significant increase from pre simulation to post-simulation confidence levels for taking history (p=.011), performing physical exam (p=.025), formulating differential diagnoses (p=.004) and for planning care (p=.008). The median and Z scores for all the competencies are presented in table 1. The change in confidence levels is reflective of level 2 Kirkpatrick learning.

All the 3 faculty who played the role of a patient reported that they would volunteer again and liked the learning experience they provided for the students. Faculty reported that students communicated in a manner which was respectful and showed sensitivity when discussing uncomfortable topics.

The researcher coordinated the simulation with the faculty patients, the lab and the technician. Resources already available such as lab space, a laptop computer and mannequin were arranged with ease. There was no cost involved in the study. The flexible nature of the simulated scenario depended on participant interaction with the faculty patient and required minimal training. Planning, scheduling and communication were important to ensure faculty availability and understanding of the role and the scenario. Overall, from cost and time standpoint it is feasible to conduct simulations using nursing faculty for playing patient roles.

Discussion

This study and the results highlight the importance of using creativity and innovation in nursing education to improve student preparation for the NP role. A statistically significant improvement in self-confidence for performing select NP competencies was achieved with simulation using faculty patients. Higher levels of statistical significance were achieved for confidence levels in developing differential diagnosis and planning care compared to the history taking and performing physical exam. The results can be explained by the following a) Registered professional nurses do not formulate differential diagnosis and plan of care hence their pre-simulation scores for these competencies were lower which made more room for improvement b) students shared their thoughts, discussed them within the group and worked as a team along with the faculty to generate possible hypothesis, ruled in and ruled out conditions from the list of differential diagnoses and this activity may have enhanced learning and confidence levels in formulating differential diagnosis and plan of care.

The result of our study is comparable to other studies in which OSPs were used [2]. Studies included in the systematic review by Chua et al, were heterogenous but reported improved perceived confidence levels post-simulation. These findings support the use of faculty for the role of standardized patients in limited resource educational institutions at a global level.

In the Traditional Chinese Medicine study, Huang et al. reported that the faculty patients may have “unconsciously” led the students to the correct answers [6]. They reported that the students may have arrived at the correct diagnosis from prompted response by the faculty patients. However, this phenomenon was not observed in this study by the researcher. The FSPs played the role as a patient and did not prompt or sway the students toward the desired responses. The participants came up with a broad set of differential diagnoses which included the main working diagnosis in 3 out of the 4 simulation scenarios.

Limitations

There were several limitations to our study. One of the FSPs reported that students communicated with her as a faculty member and healthcare provider and not as a patient, she commented, “they didn’t stay in the role”. Also, a control group using OSPs and the same scenarios could have helped in making comparisons and strengthening the findings. The participation in simulations was optional and was conducted outside of the scheduled class time which resulted in a smaller number of participants. Better coordination with the lab personnel, students and faculty could have resulted in a larger number of student participants and more time for debriefing.

Also, assessments of the effectiveness were conducted immediately post-simulation, and it measured perceived self-confidence. Measurement of confidence levels with objective and validated instruments and at a different time point could have strengthened the findings. Although with the one-group design the influence of the independent variables remains the same, we did not report on the influence of years of experience, work setting and roles on confidence levels. Also, the participants self-selected to participate in the simulation which may have led to bias towards more favorable results. The small sample size and the self-selection of the participants limit the generalizability of the results.

Each of the four simulations was conducted once. And each student participated in one aspect of the patient encounter. Their learning could have been enhanced if each student was assigned to one whole patient encounter. Because there was no repetition of the scenario for learning, and the simulation was conducted as formative assessments, there was only minimal training required for this low-level of standardization. Hence, there may be limitations in applicability to simulations which require higher levels of standardization such as summative assessments. Finally, the researcher participating in the simulation as a facilitator may have also unintentionally introduced bias.

Conclusion

The improved outcomes for simulation using FSPs could serve as a path forward for employing simulation and conducting simulation related research in nursing educational programs in low resource colleges. Using nursing faculty for the role of SP in simulation is a feasible and cost-effective pedagogical tool which could be leveraged for NP education. Future research should focus on larger samples and compare the effect of simulation outcomes using FSPs, OSPs and traditional didactic teaching. Assessment of higher level of learning guided by the Kirkpatrick Evaluation Model could be explored further to collect and strengthen evidence in support for including simulation in the nurse practitioner curriculum.

Competing Interests:

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors are immensely grateful to Kathleen Douris APRN-BC, MSN and Janna Adler APRN, MSN, for their contribution towards the development of scenario scripts, and Marcia Brown, chief lab technician, for her technical support.

References

Healthcare Simulation Dictionary. 3rd edition. View

Chua, C. M., Nantsupawat, A., Wichaikhum, O. A., Shorey, S., (2023). Content and characteristics of evidence in the use of standardized patients for advanced practice nurses: A mixed-studies systematic review. Nurse Education Today. Jan 1;120:105621. View

Hammersla, M., Idzik, S., Williams, A., Quattrini, V., Windemuth, B., Culpepper, N., Galik, E., Jackson-Parkin, M., Koo, L.W., (2023). An innovative strategy for teaching diagnostic reasoning: cough, cough, cough. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners. Oct 1;19(9):104743. View

Beebe, S. L., McNelis, A. M., El-Banna, M., Dreifuerst, K. T., Zhou, Q. P., (2024). Nailing the diagnosis: using screen-based simulation to improve factors of diagnostic reasoning in family nurse practitioner education. Clinical Simulation in Nursing. Jun 1;91:101528. View

Nye, C., Campbell, S. H., Hebert, S. H., Short, C., Thomas, M., (2019). Simulation in advanced practice nursing programs: A North-American survey. Clinical Simulation in Nursing. Jan 1;26:3-10. View

Huang, M., Yang, H., Guo, J., Fu, X., Chen, W., Li, B., Zhou, S., Xia, T., Peng, S., Wen, L., Ma, X., (2024). Faculty standardized patients versus traditional teaching method to improve clinical competence among traditional Chinese medicine students: a prospective randomized controlled trial. BMC Medical Education. Jul 24;24(1):793.

Sibley, S., Robinson, K. N., (2024). Nurse Practitioner Education: Recommending Theories and Frameworks for Simulation-Based Experiences and Research. Journal of Professional Nursing. Sep 1;54:50-3. View

Johnston, S., Coyer, F. M., Nash, R., (2018). Kirkpatrick's evaluation of simulation and debriefing in health care education: a systematic review. Journal of Nursing Education. 1; 57(7):393-8.View

Goh, P. R., Ng, G. Y., Shorey, S., Lim, S., (2023). Impacts of standardized patients as a teaching tool to develop communication skills in nursing education: A mixed-studies systematic review. Clinical Simulation in Nursing. Nov 1;84:101464. View

Miranda, F. M., Santos, B. V., Kristman, V. L., Mininel, V. A., (2025). Employing Kirkpatrick’s framework to evaluate nurse training: an integrative review. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem. Feb 3;33:e4431. View

National Task Force on Quality Nurse Practitioner Education. Standards for Quality Nurse Practitioner Education: A report of the National Task Force on Quality Nurse Practitioner Education, 6th Edition [Internet]. 2022. View

Jeffries, P. R., Slaven-Lee, P., (2024). A Practical Guide for Nurse Practitioner Faculty Using Simulation in Competency- based Education. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Jan 9. View

Rivière, E., Jaffrelot, M., Jouquan, J., Chiniara, G., (2019). Debriefing for the transfer of learning: the importance of context. Academic Medicine. Jun 1; 94(6):796-803. View