Journal of Comprehensive Nursing Research and Care Volume 10 (2025), Article ID: JCNRC-219

https://doi.org/10.33790/jcnrc1100219Research Article

Ascertaining the Views of Hereditary Cancer Syndrome Patients Receiving Genetic Counseling and Their Families Regarding Genetic Testing

Yoshie IMAI1*, Yoko Miyamoto2, Yukiko Yoshida2, Yuta Inoue1, Hironori Imai3, Kazuyo Yamada2, Tomoka Sakamoto1, and Hiroyuki Morino1,

1University of Tokushima, Japan.

2Tokushima University Hospital, Japan.

3Wakayama Medical University, Japan.

Corresponding Author Details: Yoshie IMAI, Tokushima University, 3-18-15 Kuramoto-cho, Tokushima, 770-8509, Japan.

Received date: 11th August, 2025

Accepted date: 03rd December, 2025

Published date: 05th December, 2025

Citation: IMAI, Y., Miyamoto, Y., Yoshida, Y., Inoue, Y., Imai, H., Yamada, K., Sakamoto, T., & Morino, H., (2025). Ascertaining the Views of Hereditary Cancer Syndrome Patients Receiving Genetic Counseling and Their Families Regarding Genetic Testing. J Comp Nurs Res Care 10(2):219.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

This study investigates how genetic information could be shared by ascertaining the views of patients receiving genetic counseling (GC) for suspected hereditary cancer and their families regarding genetic testing. We conducted a questionnaire survey of hereditary cancer syndrome patients receiving GC for the first time after the disclosure of genetic testing results as well as their spouses and at-risk relatives. A total of 81 people responded: 50 patients who received GC during the study period, 18 spouses, and 13 at-risk relatives. We found significant differences in responses to the questions “1-1: Are you interested in genetic testing?” (p < .003), “1-5: Do you think genetic testing has drawbacks?” (p < .007), “1-9: Is it necessary to undergo genetic testing?” (p < .001), and “Q2: How did you think about communicating genetic information to family or relatives?” (p < .003) between patients and spouses. There was a significant difference among all groups for “1-4: Do you want to clarify whether you have a genetic variant or not?” (p < .001). We also found a significant difference in the question “1-11: Is genetic testing too expensive?” between patients on one side and spouses and at-risk relatives on the other (p < .001). We surveyed the views on genetic testing of hereditary cancer syndrome patients and their families and found that both groups recognize the importance of learning the test results. However, the two groups did not agree on “Do you want to clarify whether you have a genetic variant or not?” through genetic testing.

Keywords: Genetic Counseling, Hereditary Cancer Syndrome Patients, Genetic Testing

Introduction

The importance of genomic medicine is steadily increasing with the advancement of genomic analysis studies. Core Hospitals for Cancer Genomic Medicine are being designated nationwide in Japan, providing oncological care, information, and patient and family support as well as facilitating regional collaboration in the treatment of cancer. It is expected that the role of genetic counseling (GC) will become even greater as the importance of genetic testing is recognized and becomes more mainstream. We must therefore prepare for an era in which whole-genome analysis is commonplace in Japan.

Genetic information among blood relatives overlaps and its influence is not limited to just one person [1]. This creates a dilemma regarding the disclosure of genetic information in GC, potentially leading to ethical issues [2]. Therefore, prior to genetic testing, there needs to be a discussion in GC regarding the reporting of the patient’s test results to blood relatives who may be at risk of some diseases [2]. However, there are numerous cases in which the patient refuses to notify at- risk relatives, even after receiving a comprehensive explanation of the importance of hereditary information [3]. Patients may perceive notifying their family of the results of genetic testing as a burden [4]. Hence, patients may opt not to share undesirable results with at- risk relatives, despite fully comprehending the importance of doing so.

There are also cases in which the patient is seemingly pressured into undergoing genetic testing by their family. Because heredity concerns not only the patient but also their blood relatives, it is presumably a difficult decision to make alone. In addition, there may be differences between patients and their non-diseased family/ blood relatives regarding psychological distress, views on risk management, and hereditary awareness [5]. Such gaps can become an obstacle to information-sharing and disclosure.

Although previous research has reported on disparities in such views, the situation concerning GC differs by country [6]. The situation in Japan likely reflects its cultural background and medical system. Therefore, this study investigates the ways in which genetic testing results should be shared in Japan by ascertaining the views on genetic testing of hereditary cancer syndrome patients who are receiving GC and their families.

The findings of this study may contribute to promoting information sharing and resolving ethical dilemmas arising from differences between patients and their families.

Genetic counseling system for hereditary cancer syndrome patients at our hospital

At our hospital, we offer GC for a broad range of questions and worries, including anxiety before testing and the disclosure of results, general worries about cancer heredity, and so on, upon referral from within and outside the hospital or according to the patient’s own wish. Based on the information given by the patient (e.g., family history), medical doctors specialized in genetics share the latest information on genetic medicine, working together with genetic counselors and nurses to provide psychological and financial support for patients. Through GC, we strive to alleviate the psychological burden on the patient and present them with the most appropriate options for treatment and prevention. Our multi-professional GC system offers seamless support to our patients and considers their psychological and familial background, enabling patients to make the best decision for themselves. It should be noted that, in Japan, non-cancer patients must pay the costs of genetic testing fully out of pocket.

Hereditary cancer syndrome patients: Patients who are at high risk of developing certain cancers. The patients in this study had developed cancer and received a diagnosis of hereditary cancer syndrome.

Spouse: In this study, spouses were married to the patients and were not related to them by blood.

At-risk relatives: In this study, at-risk relatives were related to the patients by blood, such as parents, children, and siblings, did not have cancer, and had not undergone genetic testing.

Methods

Participants

Our participants were hereditary cancer syndrome patients receiving GC for the first time as well as their spouses and at-risk relatives.

Procedures

Participants were selected by the genetic counselor performing the GC. Informed consent was obtained both orally and in writing during the waiting time before GC at the hospital by our researchers. Patients who agreed to participate completed the informed consent form and the survey, which were collected in a dedicated envelope.

Measures

We conducted a survey to examine views on genetic testing, using forms previously developed by our research team [7]. We also collected the following patient information comprising factors that influence the decision to undergo genetic testing: age [2,8-10], sex [8,9], education and occupation [2,8-9], socioeconomic status [11], marital status and history of cancer within the family [9], disease [2,8,12,13], and psychological state [12]. Family members were designated as spouses or at-risk relatives and we also collected information on their age, sex, education, occupation, socioeconomic status, family background, and psychological state (e.g., anxiety, depression). Psychological state was assessed using The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [14]. HADS is a 14-item, self-reporting screening scale consisting of two 7-item Likert scales, both of which relate to anxiety and depression; the score of each scales ranges from 0 to 21. The HADS score is calculated by summing up the rating scores of the 14 items to yield a total score, and by summing up the rating scores of the seven items of each subscale to yield separate scores for anxiety and depression (0−7; non, 8−10; doubtful, l1−21; definite).

Data analysis

We calculated the grand total and performed the Chi-square test, using SPSS Statistics ver. 29. For the descriptive statistics, the analysis was divided into three groups: patients, spouses, and at-risk relatives. In addition, the Chi-square test was used to evaluate differences between groups in awareness of genetic testing. For detailed multiple comparisons among the three groups, the Bonferroni correction was used to determine a p-value of <0.016.

Results

Participant characteristics

As shown in Table 1, participants were 50 patients who received GC during the study period, 18 spouses, and 13 at-risk relatives, for a total number of 81 participants. There were many breast cancer patients, and thus women accounted for the majority of participants. There were no participants with an abnormal psychological state.

Recognition of genetic testing among hereditary cancer syndrome patients and their families

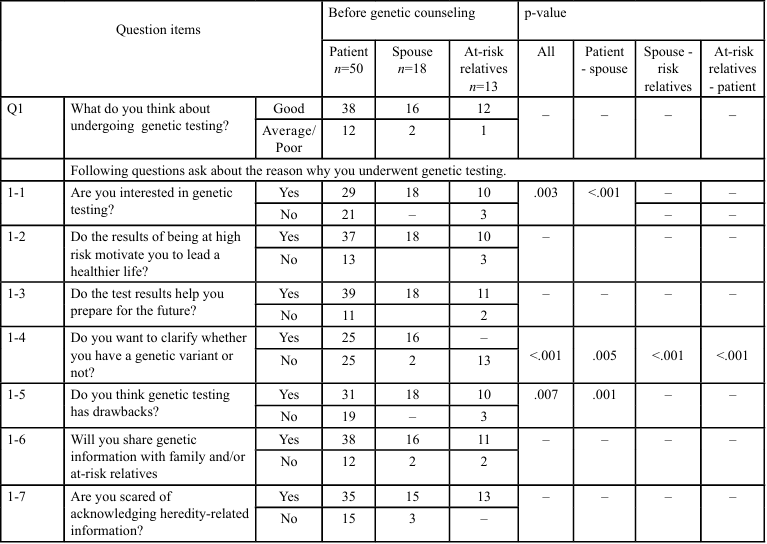

Table 2 shows the results of recognition of genetic testing among hereditary cancer syndrome patients and their families. For Question 1, 66 participants (81.2%) answered that undergoing genetic testing was good for them. For Question 2, 54 participants (66.6%) answered that communicating genetic information to family and/or relatives was good. More than 60 participants answered “Yes” to the following five questions: “1-2 : Do the results of being at high risk help you motivate you to lead a healthier life?” (80.2%), “1-3 : Do the test results help you prepare for the future?” (84%), “1-6: Will you share genetic information with family and/or at-risk relatives?” (80.2%), “1-7: Are you scared of acknowledging heredity-related information?” (77.8%), and “2-1: Is it better to know the results?” (92.6%).

Table 2: Recognition of genetic testing among hereditary cancer syndrome patients and their families

In contrast, more than 60 participants answered “No” to the following six questions: “1-8 Are you at a disadvantage in terms of life insurance, mortgages, and interpersonal relationships?” (86.4%), “1-10: Are you unsure how to accept the results?” (80.2%), “2-6: Do you lack confidence to communicate the results to others?” (74.1%), “2-7: Are you afraid your privacy may be violated?” (76.5%), “2-8: Will you never share the information with others?” (84%), and “2-11: Do you feel a sense of guilt?” (86.4%).

Significant differences in recognition were found among patients, their spouses, and at-risk relatives in the following six items: “1-1: Are you interested in genetic testing?” (p < .003), “1- 4: Do you want to clarify whether you have a genetic variant or not?” (p < .001), “1- 5: Do you think genetic testing has drawbacks?” (p < .007), “1-9: Is it necessary to undergo genetic testing?” (p < .001), “1-11: Is genetic testing too expensive?” (p < .001), and “Q2: How did you think about communicating genetic information to family or relatives?” (p < .003).

Discussion

Shared views on genetic testing between hereditary cancer syndrome patients and their families

Twelve items on the survey received 60 responses or more in total (≥70%) and were thus considered to reflect common views between patients and their families. Specifically, both groups agreed that it is better to know the genetic testing results than not and both felt positively about undergoing genetic testing because the results would be useful for future surveillance rather than bringing disadvantages. On the other hand, both groups were afraid of learning the genetic information. This suggests that adequate comprehension of genetic testing results and their implications by the participants led them to feel positively about undergoing genetic testing. This is in line with the findings of Hitch [15], who reported that greater participation in genetic testing with the knowledge that sharing the results with relatives confers advantages such as future preparation, medical care, and prevention. In other words, greater recognition of the importance of genetic testing will lead to more people to undergo testing.

On the other hand, our results suggest that a positive view of genetic testing does not eliminate the fear of knowing the outcome. This is understandable, given that the results may reveal a high risk of cancer. This suggests that rather than eliminating this fear, it is important for medical professionals to listen to and understand what the patient is feeling.

Differences in views on genetic testing between hereditary cancer syndrome patients and their families

Items on the survey with statistical differences reflect views on genetic testing that differ between hereditary cancer syndrome patients and their families. In particular, “Do you want to clarify whether you have a genetic variant or not?” differed among all three groups, making it a highly sensitive point that needs to be handled carefully in GC. Specifically, spouses wanted to clarify the situation, whereas at-risk relatives did not, a situation that might affect the decision to undergo genetic testing. Because all groups were afraid of learning the results, it can be surmised that at-risk relatives are hesitant to undergo genetic testing. This reinforces the importance of comprehending the participants’ motivation and intention for undergoing testing. Previous research has also pointed out the difficulties of handling a situation in which at-risk relatives decline to undergo genetic testing [16,17]. This indicates the importance of assessing interfamilial relationships beforehand to determine whether it is necessary to explain the results separately to patients and their families, taking into consideration the familial background and situation.

Difference in views on how to handle genetic information were observed between patients and spouses from the survey items “Do you think genetic testing has drawbacks?” and “How did you think about communicating genetic information to family or relatives?” Spouses, but not patients, thought it was disadvantageous to undergo genetic testing and responded that they did not wish to tell their relatives, even after comprehending the importance of genetic testing and the lack of disadvantages. Family members and spouses are influential in decision-making and may put pressure on patients [18]. This suggests that it is insufficient to merely explain the usefulness of genetic testing in order to pass on the genetic information to the next generation and highlights the need to ascertain the views of not only the patient but also the spouses as well during GC.

In addition, the results revealed that the high cost of genetic testing constitutes an obstacle to undergoing testing. Previous research has reported that the higher the cost of genetic testing, the lower the number of people who undergo testing [11]. To promote genetic testing, it is necessary for insurance to cover the cost, non-cancer patients such as at-risk relatives.

Practice implications and future research

Our study showed that the view among all three groups differed for the question “Do you want to clarify whether you have a genetic variant or not?” When the spouse is leaning towards clarifying the situation, there is often pressure on testing the children; in such cases, GC should be implemented with consideration for the familial background and power balance. Caution is warranted when speaking about the genetic testing of blood relatives, making the assessment of interfamilial relationship before and after GC all the more important.

Our results also showed that simply recognizing the usefulness of genetic information does not necessarily lead to sharing genetic test results with family members and other relatives. This highlights the importance of clarifying the views of spouses during GC so that strategies can be implemented to ensure that they fully understand the meaning of the genetic testing results and to further nudge them to make good use of it for future generations.

Study limitations

Our results reflect a limited survey of just one facility. Future research should include more participants from multiple facilities in order to generalize the results. Because it is plausible that results might differ among various diseases, the characteristics of each disease must also be taken into consideration. In particular, spouses and at-risk relatives have their own life histories and medical histories; thus, generalization based solely on this study is impossible.

Conclusion

We surveyed the views on genetic testing of hereditary cancer syndrome patients and their families and found that both groups recognize the importance of learning the test results. However, the two groups did not agree on “Do you want to clarify whether you have a genetic variant or not?” through genetic testing. This shows the importance of grasping the participants’ motives and intentions for undergoing genetic testing. Our results suggest the need to continue to ascertain the views of not only the patients but also spouses and at-risk relatives as well.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Yoshie Imai, Yoko Miyamoto, Yukiko Yoshida, Yuta Inoue, Hironori Imai, Kazuyo Yamada, Tomoka Sakamoto, Toyoyuki Morino declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics Statement

Human studies and informed consent: Approval to conduct this research involving human subjects was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at Tokushima University Hospital University (IRB protocol ID 3720). All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all patients included in the study. Animal studies: No non-human animal studies were carried out by the authors for this article.

Author Contributions

Substantial contribution to the conception or design of the work: Yoshie Imai. Substantial contribution to the acquisition (Yoshie Imai, Yoko Miyamoto, Yukiko Yoshida), analysis (Yuta Inoue), and interpretation of the data (Yoshie Imai, Yoko Miyamoto, Yukiko Yoshida, Kazuyo Yamada, Hironori Imai, Tomoka Sakamoto). Drafting the work and/or revising it critically for important intellectual content: Hiroyuki Morino. All of the authors gave final approval of this version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

References

The Japanese Association of Medical Sciences. (2022). Guidelines for Genetic Tests and Diagnosis in Medical Practice. View

Letocha Ersig, A. D., Hadley, D. W., Koehly, L. M. (2009). Colon cancer screening practices and disclosure following receipt of positive or inconclusive genetic test results for Hereditary Non Polyposis Colorectal Cancer. Caner, 15; 115(18), 4071- 4079. View

Falk, M. J., Dugan, R. B., O'Riordan, M. A., Matthews, A. L., & Robin, N. H. (2003). Medical geneticists’ duty to warn at risk relatives for genetic disease. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, 120A(3), 374-380. View

Kentwell, M., Dow, E., Antill, Y., Wrede, C. D., McNally, O., Higgs, E.,… Scott, C. L. (2017). Mainstreaming cancer genetics : A model integrating germline BRCA testing into routine ovarian cancer clinics. Gynecologic Oncology, 145(1), 130-136. View

Keller, M., Jost, R., Haunstetter, C. M., Sattel, H., Schroeter, C., Bertsch, U.,… Brechtel, A. (2008). Psychosocial outcome following genetic risk counselling for familial colorectal cancer. A comparison of affected patients and family members. Clinical Genetics, 74(5), 414-424. View

Tamura, C. (2015). A comparison of genetic counselling in Japan and the US. Japan Family Planning Association.

Imai, Y., Miyamoto, Y., Yoshida, Y., Abe, A., Murakami, Y., Kawasaki, Y.… Bando, T. (2020). A Literature Review on the Trend of Genetic Counseling about Familial Tumor. SHIKOKU ACTA MEDICA Online Journal, 76(1,2), 45-54.

Burton, A. M., Peterson, S. K., Marani, S. K., Vernon, S. W., Amos, C. I., Frazier, M. L.… Gritz, E. R. (2010). Health and lifestyle behaviors among persons at risk of Lynch syndrome. Cancer Causes Control, 21(4), 513-521. View

Gilbar, R., Shalev, S., Spiegel, R., Pras, E., Berkenstadt, M., Sagi, M.… Barnoy, S. (2016). Patients' Attitudes Towards Disclosure of Genetic Test Results to Family Members: The Impact of Patients' Sociodemographic Background and Counseling Experience. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 25(2), 314-324. View

Werner-Lin, A., Ratner, R., Hoskins, L. M., & Lieber, C. (2015). A survey of genetic counselors about the needs of 18-25 year olds from families with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 24(1), 78-87. View

Gallagher, T. M., Bucciarelli, M., Kavalukas, S. L., Baker, M. J., & Saunders, B. D. (2017). Attitudes Toward Genetic Counseling and Testing in Patients With Inherited Endocrinopaties. Endocrine Practice, 23(9), 1039-1044. View

Flores, K. G., Steffen, L. E., McLouth, C. J., Vicuña, B. E., Gammon, A., Kohlmann, W.… Kinney, A. Y. (2017). Factors Associated with Interest in Gene-Panel Testing and Risk Communication Preferences in Women from BRCA1/2 Negative Families. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 26(3), 480 490. View

Celine H. M. L., Mariska, D. H., Conny, D. D. M., Ernst, J. K., Monique, E. V. L., Anja, W. (2016). Genetic testing for Lynch syndrome: family communication and motivation. Familial Cancer, 15(1), 63-73. View

Zigmond, A. S., & Snaith, R.P. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67(6), 361- 370. View

Hitch, K., Joseph, G., Guiltinan, J., Kianmahd, J., Youngblom, J., & Blanco, A. (2014). Lynch syndrome patients' views of and preferences for return of results following whole exome sequencing. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 23(4), 539-551. View

Cowley, L. (2016). What can we Learn from Patients' Ethical Thinking about the right 'not to know' in Genomics? Lessons from Cancer Genetic Testing for Genetic Counselling. Bioethics, 30(8), 628-635. View

Hawranek, C., Rosén, A., & Hajdarevic, S. (2024). How hereditary cancer risk disclosure to relatives is handled in practice - Patient perspectives from a Swedish cancer genetics clinic. Patient Education and Counseling, 126, 108319. View

Gilbar, R., & Barnoy, S. (2018). Companions or patients? The impact of family presence in genetic consultations for inherited breast cancer: Relational autonomy in practice. Bioethics, 32(6), 378-387. View