Journal of Comprehensive Nursing Research and Care Volume 10 (2025), Article ID: JCNRC-220

https://doi.org/10.33790/jcnrc1100220Review Article

Risk Factors and Current Evidenced Based Strategies in the Management of Pediatric Obesity

Judy Harkins*, DNP, RN, APN, PPCNP-BC, IBCLC, and Vicki Brzoza, PhD, MBA, RN, CCRN

Department of Nursing, The College of New Jersey, Ewing, NJ, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Judy Harkins, DNP, RN, APN, PPCNP-BC, IBCLC, Assistant Professor, Department of Nursing, The College of New Jersey, Ewing, NJ, United States.

Received date: 21st August, 2025

Accepted date: 03rd December, 2025

Published date: 05th December, 2025

Citation: Harkins, J., & Brzoza, V., (2025). Risk Factors and Current Evidenced Based Strategies in the Management of Pediatric Obesity. J Comp Nurs Res Care 10(2):220.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Pediatric obesity is a major driver of rising healthcare costs and decreased quality of life. For this paper, a review of the risk factors and current treatment strategies for this disease was conducted, including lifestyle, pharmacological, and surgical. Despite current options in treatment, it appears that success is still limited in treating obesity long-term in children and adolescents. However, nursing can play a key role in stemming the tide, touching working with patients and families starting from the prenatal family. A cross-disciplinary, lifelong preventive approach may be the only option for stemming the tide of pediatric obesity.

Background

The complex nature of obesity in the pediatric population is an ongoing challenge for both primary care and related specialties. Known risk factors exist, such as during pregnancy, where maternal obesity and smoking can contribute to pediatric obesity. Both behavioral and biological, a child’s risk of becoming obese increases significantly during early and middle childhood, making this period a crucial time for prevention. Risk for development of obesity lessens in adolescence if the child is of normal weight. Overall risk of obesity has continued to rise over time. Between 1975 and 2016, global rates rose from 0.9% to 7.8% for boys and 0.7% to 5.6% for girls, with the largest increases between 2012 and 2023 [1], reaching over 16% for all 18-year-olds by 2022 [2]. Large disparities between countries exist, with wealthier countries seeing rates higher than the global average, and the United States leading the way at 20%, which can be attributed to infrastructure deficits, such as inadequate investment in the creation of safe, healthy communities, and easy access to unhealthy food and drinks, which also have intense marketing campaigns connected to them [3].

Pediatric obesity contributes to disease processes throughout the body, affecting all body systems. Included in the long list are complications such as slipped femoral capitis epiphysis, joint pain and arthritis, gastroesophageal reflux disease, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, chronic headaches, asthma, acanthosis nigricans, anxiety and depression [4].

The following article contains a summary of the most common, and yet most significant, health risks associated with pediatric obesity. The role of the nurse, treatment options and practice guidelines are reviewed.

Cardiovascular Risk, Carried in to Adulthood

Cardiovascular risk, the role of inflammation and further complications rise with obesity rates. The literature clearly demonstrates the increased risk of cardiovascular disease, as obesity contributes to conditions such as hypertension and type II diabetes independently, often before the age of 18 [5,6]. Consumption of ultra- processed foods, such as convenience and take-out, and processed foods, such as breads and cheeses, and sugary drinks can contribute to both hypertension and obesity [7]. Obesity and hypertension, combined with hypercholesterolemia (most notable, triglycerides), and increased fasting glucose create the most consequential complication of obesity-related conditions, metabolic syndrome. The risk of cardiovascular events increases exponentially with the onset of metabolic syndrome, and in children, a waist circumference of >90th percentiles, and the resulting oxidative stress, are particularly concerning, and closely related to cardiovascular risk [8]. Children are also particularly susceptible to developing adult-like disease, carrying it forward into adulthood. When Hannon and Arslanian [3] examined the direct risk of stroke and sudden death from a cardiac event in adulthood, the authors found in adolescents with the single component of BMI of above the 85th percentile, risk more than doubled. At the 90th percentile or higher, the risk was 3-fold. Disruptions in sleep and mental health can also occur as weights rise, followed by obstructive sleep apnea, which can further increase the risk of metabolic disease and cardiovascular events [9].

Hormonal and Gut Microbiota Disruption

The endocrine disorder polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is closely associated with pediatric obesity, can result in the development of type II diabetes at a younger age, and typically associated with dyslipidemia and hypertension, which increases overall cardiovascular risk [10]. The cycle created by endocrine-disrupting chemicals, such as phthalates and BPA, can both contribute to obesity rates, and cardiovascular risk, by disturbing hormonal balances in the thymus, thyroid, and reproductive systems, resulting in obesity and widespread, chronic inflammation [11].

Childhood obesity is also associated with disrupting the balance in the gut microbiota, and decreases the diversity within it. One of the responsibilities of the gut microbiota is the breakdown of fatty acids and subsequent production of compounds, such as butyrate, which assists in regulating hunger hormones and cholesterol production [12]. The stress of over-consumption of calorie-dense foods, ultra- processed foods and sugary beverages have been attributed to the development of obesity in children, while simultaneously, obese children will often suffer from micronutrient deficiencies. These can include iron, vitamin C and fat-soluble vitamins A and E. Iron, in particular, is of a concern, as the pro-inflammatory cytokines produced in individuals who are obese can contribute to the over- production of hepcidin in the liver, which helps to regulate iron by preventing its absorption of by the intestine, while promoting its degradation in the cell. Both vitamins C and E play important roles in leptin production, the hormone responsible for suppressing hunger when adequate energy intake occurs. In children with low vitamin C and/or E levels, leptin production in adipose tissue decreases. Lastly, vitamin A deficiency is associated with decreased adipogenesis, one of its major functions [13].

Current Strategies and Practice Guidelines

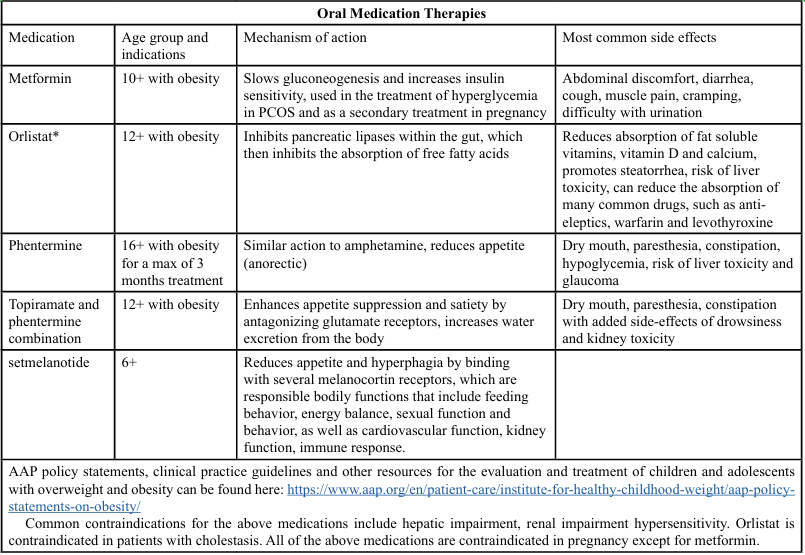

In 2023, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) updated its clinical practice guidelines for obesity in children. The Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Obesity includes and executive summary and treatment algorithm clarifying pediatric obesity’s designation as a complex, chronic disease, while creating a concise pathway for long term treatment and support. The chronic disease model allows for a holistic view, taking into account developmental status, environment, family dynamics and history, co-morbidities and socioeconomic challenges. Long-term treatment plans should include family input, and services such as cognitive behavioral therapy and medical monitoring [14]. However, therapies have expanded, with a variety of treatment options that now include pharmacologic therapies (Table 1, 2) and non-pharmacologic therapies.

Surgical Interventions

According to Calcaterra et al [4], though still not widely available nor accepted, the use of bariatric surgery in the pediatric population is growing. Bariatric surgery involves a commitment that is life changing and permanent. Further, a normal BMI may not be achievable for all patients due to surgery alone; reduction in BMI and overall metabolic risk are often the goals [15]. Current guidelines from the European Association of Endoscopic Surgery propose surgery in patients with a BMI =/> 40 (greater than the 99.5th percentile) or >35 with comorbidities. The preferred procedure is laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG), due to its safety record and level of success long-term, compared with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), with some studies showing significant complications after LSG as low as 4.3% [4]. Mithany et al. [16] found that although LSG patients experience higher rates of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), they have fewer post-operative complications and less frequent need for surgical revision than their RYGB counterparts. Other common complications include volvulus, nausea, vomiting, dehydration and gastric tube twist [4]. In up to 15% of patients, hernias and adhesions can occur, which may require additional surgical procedures [17]. Infection, bowel obstruction and thromboembolism can be added to the short-term complications listed here. However, long-term complications, such as GERD with Barrett’s esophagus and increased visceral fat can develop. Rapid gastric emptying, altered stomach secretions and potential bypassing of the duodenum can lead to micronutrient deficiencies, most notably B12, D and iron, up to 5 years post-surgery. Reversal or revision due to treatment failure can also result, with no clear guidelines in place for what conditions define treatment failure. Failure can be categorized as poor levels of primary weight loss, or resulting persistent comorbidities such as hypertension and type 2 diabetes [15].

For families, risk of complications must be weighed against the risk of metabolic changes that can occur in children with obesity such as cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and overall increased risk of mortality. Prior to surgery, a holistic, multidisciplinary approach is taken, which includes the following [4]:

• At least 6 months of lifestyle changes for weight loss, in a tertiary care center specializing in pediatric obesity

• A complete skeletal and sexual maturation assessment

• Informed consent that includes an understanding of the risks and benefits of the procedure

• A comprehensive medical and psychological evaluation before and after surgery

• A commitment to ongoing, long-term, post-surgical evaluation and treatment

• Active participation in a post-surgery, for specialized multidisciplinary program surgery access in a unit with specialist pediatric support

Clients who can be treated medically are excluded from eligibility. Other contraindications for surgery include pregnancy or planned pregnancy, mental health concerns that may interfere with treatment including clients with eating disorders. Clients with substance use disorders must be at least one year out from active use [4].

Nursing’s role in both non-pharmacological and non-surgical interventions

The management of pediatric obesity requires a multidisciplinary approach; however, most interventions can be effectively implemented by nursing professionals within their scope of practice. Care coordination, including the management of appointments for both primary care and specialty areas, and navigation of weight management protocols are examples of where the nurse can play a significant role. This may include in-person or telemedicine experiences, allowing for patient and family eduction about accessing community resources and other providers within the multidisciplinary team, and basic preventative measures that can be taken before, during and after treatment [18].

Weight loss should be individualized and interventions which would normally work for an adult may not work for children. Children benefit from structured, incremental goal-setting, targeted motivational strategies, and positive reinforcement of desired behaviors. Goals should be structured as short-term, achievable milestones that align with the child’s current capabilities. While long-term objectives are valuable, they may be less feasible for a child who has consistently experienced lifestyle patterns that put them at increased risk. Motivational strategies involve promoting weekly self-weighing as a means to monitor progress and reinforce positive behaviors [17]. Wearable Artificial Intelligence (AI) is also a strategy where children can play games or receive immediate feedback focusing on healthy nutritional choices and physical activity [19]. Positive reinforcement includes teaching parents about limit setting, reducing stress, and family role modeling behavior. Greater levels of parental involvement are associated with improved treatment outcomes and enhanced intervention effectiveness [14]. Educational interventions targeting lifestyle changes should be directed toward the entire family, with the goal of facilitating behavior change in both the child and the family unit. Preventative behavioral interventions which can be taught by the nursing professional include the following [17]:

• Promoting healthier dietary choices and encouraging increased levels of physical activity

• Limiting or eliminating the intake of ultra-processed foods

• Developing conscious awareness while eating, focusing on the meal instead of any distractions such as television or gaming

• Self-regulating meals where the child chooses and consumes a meal that is an appropriate portion size and variety of food

• Maintaining records of dietary intake and physical activity levels to evaluate progress

• Advocating for adequate sleep and limited screen time

Significant challenges to providing interventions and achieving healthy weights in children exist. Concerns surrounding social determinants of health, such as the effects of poverty and lack of access to healthy food options within food deserts, the abundance of cheap and highly processed foods that exist within food swamps, and lack of adequate pediatric obesity services are at forefront of pediatric obesity management [20].

Bodepudi and colleagues [21] found that providers often find it difficult to educate families on pediatric obesity and common progression of the disease. Caregivers are susceptible to underestimating their child’s weight and risk factors, while simultaneously believing that weight reduction automatically comes with age. Concurrently, stigma and bias associated with obesity can be difficult to overcome, as it is pervasive among caregivers, clinicians and in the public sphere, through marketing and social media. Further complicating effective treatment, Bodepudi, et al. [21] also found that only 7% of Louisiana based pediatricians follow current guidelines for referral of children with obesity, citing limited community resources and low confidence levels in their ability to provide obesity care in the primary care setting.

The trust that patients and families have in nursing as a profession is well documented. Beyond preventive behavioral interventions, nursing can provide consistent contact with families of children with obesity, opening up opportunities to address barriers and gaps in care that children and families experience.

Conclusion

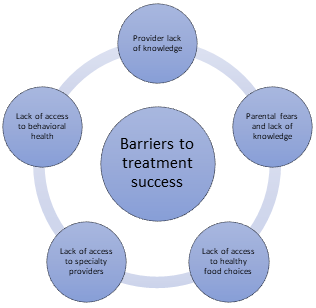

Childhood obesity is an epidemic with significant health costs that requires prevention prenatally, then moving forward throughout childhood. Despite current options in treatment, including pharmacological, non-pharmacological, surgical and lifestyle, it appears that success is still limited in treating obesity long term in children and adolescents. In order to prevent the complications incurred during adulthood, a more holistic, and in many cases more aggressive, treatment program may be required for some. However, this requires addressing issues and barriers surrounding treatment, such as lack of access to care, provider lack of knowledge and confidence, parental fears and need for assistance in decision making, and shortages in the behavioral health sector (Figure 1). Nursing is well positioned to guide pediatric patients and their families, as they navigate this complicated disease. Nursing can play a key role in stemming the tide, through a frequent touch approach, working with patients and families starting prenatally. It is clear that a cross discipline, life-long preventative approach may be the only option for stemming the tide of pediatric obesity.

References

Zhang, X., Liu, J., Ni, Y., Yi, C., Fang, Y., Ning, Q., Shen, B., Zhang, K., Liu, Y., Yang, L., Li, K., Liu, Y., Huang, R., & Li, Z. (2024). Global prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatrics, 178(8), 800. View

World Health Organization (7, May, 2025) Obesity and overweight. View

Hannon, T. S., & Arslanian, S. A. (2023). Obesity in adolescents. New England Journal of Medicine, 389, 251–261. View

Calcaterra, V.; Cena, H.; Pelizzo, G.; Porri, D.; Regalbuto, C.; Vinci, F.; Destro, F.; Vestri, E.; Verduci, E.; Bosetti, A. (2021). Bariatric surgery in adolescents: To do or not to do? Children, 8, 453. View

Cioana, M., Deng, J., Nadarajah, A., Hou, M., Qiu, Y., Chen, S., Rivas, A., Banfield, L., Alfaraidi, H., Alotaibi, A., Thabane, L., & Samaan, M. (2022). Prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome in patients with pediatric type 2 diabetes. JAMA Network Open, 5(2), e2147454. View

Falkner, B., Gidding, S. S., Baker-Smith, C. M., Brady, T. M., Flynn, J. T., Malle, L. M., South, A. M., Tran, A. H., & Urbina, E. M. (2023). Pediatric primary hypertension: An underrecognized condition: A scientific statement from the american heart association. Hypertension, 80(6). View

Vallianou, N. G., Kounatidis, D., Tzivaki, I., Zafeiri, G., Rigatou, A., Daskalopoulou, S., Stratigou, T., Karampela, I., & Dalamaga, M. (2025). Ultra-processed foods and childhood obesity: Current evidence and perspectives. Current Nutrition Reports, 14(1). View

Hertiš Petek, T., & Marčun Varda, N. (2024). Childhood cardiovascular health, obesity, and some related disorders: Insights into chronic inflammation and oxidative stress. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(17), 9706. View

Panetti, B., Federico, C., Sferrazza Papa, G., Di Filippo, P., Di Ludovico, A., Di Pillo, S., Chiarelli, F., Scaparrotta, A., & Attanasi, M. (2025). Three decades of managing pediatric obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: What's old, what's new. Children, 12(7), 919. View

Cioana, M., Deng, J., Nadarajah, A., Hou, M., Qiu, Y., Chen, S., Rivas, A., Banfield, L., Toor, P., Zhou, F., Guven, A., Alfaraidi, H., Alotaibi, A., Thabane, L., & Samaan, M. (2022a). The prevalence of obesity among children with type 2 diabetes. JAMA Network Open, 5(12), e2247186. View

Stathori, G., Hatziagapiou, K., Mastorakos, G., Vlahos, N. F., Charmandari, E., & Valsamakis, G. (2024). Endocrine disrupting chemicals, hypothalamic inflammation and reproductive outcomes: A review of the literature. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(21), 11344. View

Verduci, E., Bronsky, J., Embleton, N., Gerasimidis, K., Indrio, F., Köglmeier, J., de Koning, B., Lapillonne, A., Moltu, S., Norsa, L., & Domellöf, M. (2021). Role of dietary factors, food habits, and lifestyle in childhood obesity development. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 72(5), 769–783. View

Calcaterra, V., Verduci, E., Milanta, C., Agostinelli, M., Todisco, C., Bona, F., Dolor, J., La Mendola, A., Tosi, M., & Zuccotti, G. (2023). Micronutrient deficiency in children and adolescents with obesity—a narrative review. Children, 10(4), 695. View

Hampl, S. E., Hassink, S. G., Skinner, A. C., Armstrong, S. C., Barlow, S. E., Bolling, C. F., Avila Edwards, K. C., Eneli, I., Hamre, R., Joseph, M. M., Lunsford, D., Mendonca, E., Michalsky, M. P., Mirza, N., Ochoa, E. R., Sharifi, M., Staiano, A. E., Weedn, A. E., Flinn, S. K.,...Okechukwu, K. (2023). Executive summary: Clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and treatment of children and adolescents with obesity. Pediatrics, 151(2). View

Lamoshi, A., Chernoguz, A., Harmon, C. M., & Helmrath, M. (2020). Complications of bariatric surgery in adolescents. Seminars in Pediatric Surgery, 29(1), 150888. View

Mithany, R. H., Shahid, M., Ahmed, F., Javed, S., Javed, S., Khan, A., & Kaiser, A. (2022). A comparison between the postoperative complications of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (lsg) and laparoscopic Roux-en-y gastric bypass (rnygb) in patients with morbid obesity: A meta-analysis. Cureus. View

Mittal, M., & Jain, V. (2021). Management of obesity and its complications in children and adolescents. Indian Journal of Pediatrics, 88(12), 1222–1234. View

O'Hara, V. M., Johnston, S. V., & Browne, N. T. (2020). The paediatric weight management office visit via telemedicine: Pre- to post-covid-19 pandemic. Pediatric Obesity, 15(8). View

Adjei, F. (2025). A concise review on identifying obesity early: Leveraging ai and ml targeted advantage. SSRN Electronic Journal. View

Williams, M. S., McKinney, S. J., & Cheskin, L. J. (2024). Social and structural determinants of health and social injustices contributing to obesity disparities. Current Obesity Reports, 13(3), 617–625. View

Bodepudi, S., Hinds, M., Northam, K., Reilly-Harrington, N. A., & Stanford, F. (2024). Barriers to care for pediatric patients with obesity. Life, 14(7), 884. View

Rena, G., Hardie, D. G., & Pearson, E. (2017). The mechanisms of action of metformin. Diabetologia, 60, 1577–1585. View

Ryan, P. M., & Hamilton, J. K. (2022). Practical Tips for Paediatricians What do I need to know about liraglutide (Saxenda), the glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist for weight management in children with obesity? Paediatrics & Child Health, 27, 201–202. View

Stat Pearls, Ansel, A., Patel, P., & Al Khalili, Y. (2024NCBI). Orlistat (Updated 2024 Feb 14). NCBI. View

Stat Pearls, Johnson, D., & Quick, J. (2025). Topiramate and phentermine (Updated 2023 March 27). NCBI. View

Stat Pearls, Hussain, A., & Farzam, K. (2025). Setmelanotide (Updated 2023 Jul 2). NCBI. View

Paschou, S. A., Shalit, A., Gerontiti, E., Athanasiadou, K. I., Kalampokas, T., Psaltopoulou, T., Lambrinoudaki, I., Anastasiou, E., Wolffenbuttel, B. H., & Goulis, D. G. (2024). Efficacy and safety of metformin during pregnancy: an update. Endocrine, 83, 259–269. View

Mayo Clinic (2025) Metformin; oral route Obtained. View