Journal of Comprehensive Social Science Research Volume 2 (2024), Article ID: JCSSR-106

https://doi.org/10.33790/jcssr1100106Research Article

Let the Students Talk. Student Perception of Automatic Textbook Billing in a Small Liberal Art Public State University

Nicolas P. Simon1, and Maryanne Clifford2*,

1Department of Sociology, Anthropology, Criminology, and Social Work, Eastern Connecticut State University, United States.

2Professor, Department of Economics and Finance, Eastern Connecticut State University, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Maryanne Clifford, Professor, Department of Economics and Finance, Eastern Connecticut State University, United States.

Received date: 17th July, 2024

Accepted date: 17th August, 2024

Published date: 20th August, 2024

Citation: Simon, N. P., & Clifford, M., (2024). Let the Students Talk. Student Perception of Automatic Textbook Billing in a Small Liberal Art Public State University. J Comp Soc Sci Res, 2(1): 106.

Copyright: ©2024, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

This paper will analyze the response of students at a public liberal arts university to the introduction of automatic textbook billing. This policy has created much debate as it promises cost-effectiveness, convenience and potential savings, yet has the potential to reduce student autonomy, impede transparency in textbook selections, and potentially raise student costs. As this and other institutions consider the implementation of automatic textbook billing, it is crucial to carefully weigh student input along with these concerns against the potential benefits. This paper assesses the impact and reception of this policy through a student opinion survey, as they are the primary stakeholders affected by such changes. Student feedback was strongly against such a policy and comments from students were extremely angry. They have also emphasized a preference for an opt-in option as opposed to being required to opt-out a policy, which would grant them greater autonomy and control over their participation and finances. Students noted that they were the best judge of their needs and preferences as they are capable of ensuring that any decision made is well-informed and aligned with their best interests.

Keywords: Student Choices, Automatic Textbook Billing, Textbook Costs, Qualitative Research, Education Policy

Introduction

Students, their families, and the public remain deeply concerned about the escalating cost of a college education. Over the 40 years from 1980 to 2020, the annual cost of attending a four-year college full-time increased by 180%, rising from $10,231 to $28,775 [1]. As tuition fees continue to rise [2], the financial burden on students becomes increasingly heavy, prompting faculty and institutions to actively seek ways to contain or reduce student expenses. One significant area of focus is the cost of textbooks, which can add hundreds of dollars to a student’s annual expenses. The Bureau of Labor Statistics [2] reported that from January 2006 to July 2016, college textbook prices increased by 87.5 percent, which is 24.8 percent higher than the 62.7 percent increase in college tuition and fees during the same period.

In an effort to alleviate this financial strain, some institutions have advocated for the use of low-cost textbooks and Open Educational Resources [3], while others have supported the implementation of automatic textbook billing policies. This approach aims to streamline the process of obtaining textbooks by automatically charging students for their required materials, often at a negotiated discount. Proponents argue that this system can ensure all students have access to necessary resources on the first day of class, potentially lowering overall costs through bulk purchasing and reducing the financial unpredictability of acquiring textbooks.

However, the introduction of automatic textbook billing has sparked considerable debate. While it promises convenience and potential savings, it also raises significant concerns about student autonomy, transparency, and the true cost-effectiveness of such a program. As institutions consider the implementation of automatic textbook billing, it is crucial to carefully weigh these concerns against the potential benefits. One effective way to assess the impact and reception of this policy is to directly survey students, as they are the primary stakeholders affected by such changes. Gathering student feedback can provide valuable insights into their perspectives, needs, and preferences, ensuring that any decision made is well-informed and aligned with their best interests.

Literature Review

Despite variations in findings regarding course material costs, multiple surveys consistently show that students are paying less for their course materials overall. A survey conducted by the National Association of College Stores [4] revealed that students spent an average of $285 on course materials during the 2022-2023 academic year, marking the lowest expenditure in 16 years. On average, students spent $33 per course.

The Florida Virtual Campus [5], which did four surveys between 2012 and 2022, highlight a significant decrease in textbook costs over the years. In 2012, only 44.8% of students reported paying $300 or less for their course materials during the Spring semester. By 2022, this figure had risen to 68%, indicating a substantial reduction in the financial burden of course materials for students. The data also showed no significant differences in spending between university and college students.

Additionally, the California Student Aid Commission [6], using average expenses reported by students at the University of California, California State University, California independent institutions, and California Community Colleges in the 2018-19 Student Expenses and Resources Survey (SEARS), adjusted for inflation, estimated that students spent an average of $810 on books and course material fees.

The average cost of textbooks obscures the significant variation between different academic disciplines. According to the Florida Virtual Campus [5], textbook expenses in several fields often surpass $300 per semester. These fields include Medical Science, Health Professions and Related Programs, Biological and Biomedical Sciences, Business Management, Marketing and Related Support Services, and Psychology. Welding [7] used data from the National Association of College Stores [4] to illustrate the average spending on course materials by college students across different majors for the academic year 2022-2023. While most courses primarily rely on textbooks, some require additional materials such as software, art supplies, or graphing calculators, which further contribute to the overall cost. Welding's data reveals significant disparities between majors. Students majoring in political or law-related fields ($389), health professions and clinical sciences ($383), and marketing or accounting ($378) paid considerably more for their course materials compared to those majoring in computer science ($229), education ($228), physical sciences ($219), or mathematics ($174).

To reduce costs, students have developed various strategies. One way students reduce the cost of course materials is by renting digital copies, despite their preferences for paper versions [5]. Another option is to shop around to find the cheapest option. The National Association of College Stores [4] found that campus stores were the primary source for over half (56%) of these purchases, while 18% were made through Amazon, with the remaining purchases split between publisher websites and other sources. This finding aligns with those of Barnes & Noble College [8].

The Florida Virtual Campus [5] found that students are increasingly using their campus bookstores to purchase or rent course materials. In 2016, 36.2% bought books from their campus bookstore, a figure that increased to 49.4% in 2022. Another strategy students employ is not buying or renting the course materials at all. This practice decreased from 66.6% in 2016 to 53.5% in 2022, highlighting the negative consequences of high textbook prices. However, it appears that more privileged students are more likely to forgo purchasing or renting course materials. Referring to the Student Voice survey, Flaherty [9] highlighted the inequity caused by differences in cultural and economic capital regarding students' behaviors in accessing course materials. Flaherty noted that 56 percent of upper-middle class students reported avoiding buying or renting a book for a class, compared to 46 percent of lower-income students. Similarly, 56 percent of continuing-generation students said they avoided purchasing course materials, compared to 46 percent of first generation students. Furthermore, white students were more likely than students from other racial groups to avoid buying or renting a book for a class, as were men compared to women. This suggests that students who have more resources are developing strategies to avoid purchasing or renting course materials, treating them as unnecessary expenses.

In addition to individual strategies used by students, institutions have developed different strategies to help control students costs. One of them is Inclusive Access. In the 7th edition of the Student Pulse survey conducted by Barnes & Noble College in April and May 2023, 163,000 students from American public and private 2-year and 4-year institutions shared their insights. The survey found that 88% of “students would like to access course materials bundled with tuition” (p. 3), suggesting strong backing for Inclusive Access and Automatic Textbook Billing policies. Additionally, Barnes and Noble reported that in their First Day Complete program, the name of their Inclusive Access or Automatic Textbook Program, “89% of participating students say they would recommend the program to other students. They also provide overwhelmingly positive feedback on its benefits to their academic performance and overall experience at their institution.” (p. 5) In addition of being enthusiastic on Automatic textbook billing, 75% of students express that:

An equitable access program also offers institutions a meaningful opportunity to bolster recruitment and retention: students are interested in it, and the majority say that implementing an equitable access program would improve their perception of their school. Participating students report high levels of satisfaction, improved outcomes and an increased likeliness that they will remain at their school because of the program. (p. 3)

The overly positive views of Inclusive Access, as presented by Barnes & Noble, come from an entity with a vested interest in the program and stand to benefit financially from its success. However, the financial benefits for students have been challenged by both the U.S. Public Interest Research Group [10] and a survey conducted by the Florida Virtual Campus [5] which revealed that “53.2% [of students] indicated that they did not feel that the program reduced their overall textbook costs.”

In the spring of 2024, the institution where this study takes place— part of a system that includes community colleges, state universities, and one online institution—was informed of the system office's intention to implement an automatic textbook policy for the fall 2024 semester. This study was designed to address the following questions:

1. How much money did students spend on course materials such as books and software packages in the Spring 2024 semester?

2. Would students support an Automatic Textbook Billing (ATB) policy?

3. Would students prefer an opt-out or opt-in option for an ATB policy?

To understand the relationship between these factors and student spending, detailed information about course material expenses was requested from students. Specifically, inquiries were made regarding the number of credits for which they were registered, the number of books or software packages assigned, and the methods by which these materials were acquired—whether rented, purchased, or shared. Additionally, information was sought on where these course materials were accessed. This comprehensive approach enables an analysis of students' financial expenses in relation to their course loads and their perspectives on the ATB policy.

It was hypothesized that students enrolled in courses or majors requiring expensive textbooks and software packages would support an Automatic Textbook Billing policy with an option to opt out, as this would result in cost savings. Conversely, it was posited that students in courses or majors requiring inexpensive or no textbooks and software packages would oppose such a policy, preferring the ability to opt in if it were implemented. This hypothesis was grounded in the principles of economic rational choice theory.

Economic rational choice theory helps understand how college students make decisions, particularly in accessing course materials [11-13]. According to the theory, students act as rational decision makers, carefully evaluating the costs and benefits of various options to maximize their satisfaction. When deciding how to obtain textbooks or other course resources, they consider factors such as price, convenience, and accessibility. Students may compare the cost of purchasing a new textbook with renting it, buying a used copy, or accessing a digital version. They also weigh the benefits of immediate access against the potential savings of waiting for a cheaper alternative. The theory suggests that students will ultimately choose the option that best meets their needs while minimizing costs.

Methodology

Designing the online survey

In this study, a mixed-method approach was employed to leverage the advantages of both quantitative and qualitative research, combining the strengths of both methods [14,15]. An online survey was designed, beginning with a series of close-ended questions aimed at testing the hypothesis and collecting quantitative data on students' behaviors and practices. To understand what is important to students, the meaning they attribute to their practices, and to provide them with the freedom to share their perspectives, feelings, and understanding of Automatic Textbook Billing, the survey concluded with an open ended question. This allowed students to express any significant thoughts they had on the policy.

This approach was intended to give students the opportunity to voice their views on a policy that could significantly impact them. As Divan et al. [16] highlight, qualitative methods offer a deep understanding of the core nature and essential qualities of the topic under examination. This complements the description of the practices of different groups, enriching the understanding of their behaviors and perspectives.

Data Collection

The online survey detailed in Appendix 1 was conducted during the Spring 2024 semester between Sunday March 17, 2024 and the last day of the semester, Friday May 3rd. Following the data collection protocol outlined in the Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval, students were recruited using three methods:

1. Every faculty member at the institution was contacted using the faculty distribution list.

2. Every club listed on the university website, including the Student Government Association (SGA), was reached out to.

3. Signs were posted on campus.

Interested students were invited to participate in the study by clicking on a link or using a QR code specifically created for this survey. The authors of this paper and research personnel were not authorized to share this research opportunity with the students they teach or advise to avoid any potential coercion in participating in this research.

Participants

A total of 222 undergraduate students participated in the survey. Responses from students self-identifying as graduate students were discarded, as the survey was designed to examine a policy impacting only undergraduate students. The sample exhibited an overrepresentation of women, who constituted 76.58% of the respondents, compared to 23.42% for men. In terms of racial demographics, 70.72% of participants identified as white, 13.96% as multiracial, 4.50% as Black, 4.95% as Hispanic, and 5.86% chose not to disclose this information. The class standing of respondents was distributed as follows: 4.05% were first-year students, 21.17% sophomores, 27.03% juniors, and 47.75% seniors. Additionally, 79.28% of participants were members of the School of Arts and Sciences, with 65.32% of these students in non-STEM majors. The remaining 21.26% of participants were from the School of Education and Professional Development, within which 7.66% were in the College of Business.

Data Analysis

To analyze students' perceptions of Automatic Textbook Billing (ATB), a structured coding and sub-coding methodology was employed, utilizing NVivo software for enhanced efficiency and organization. The analysis began with an initial reading of the collected qualitative responses from the open-ended survey question. Both authors independently reviewed the data to familiarize themselves with recurring themes and sentiments, which facilitated the identification of broad categories.

Following this, a coding framework was developed, incorporating major themes such as "Perception of ATB," "Explanation of Why Students Are Against the Policy," and "Negative Perception of the University." This process involved tagging text segments with relevant codes and further categorizing these into sub-codes to capture nuanced aspects of students' perspectives.

After the initial coding, a debriefing session was held to review and refine the coding framework. This session ensured consistency and agreement between the authors, leading to adjustments in the codes and sub-codes as necessary. Finally, to verify accuracy, each response was re-examined in NVivo, with the coding and sub-coding being reviewed to ensure they accurately reflected the content of the responses and that no significant information was missed.

Context matters

To gain a better understanding of the findings, the context must be presented to understand why students are so angry. The institution in which this research took place is part of a larger educational system that includes 12 community colleges, four state universities, and one online institution. In February 2024, faculty were informed that the system office intended to implement an automatic textbook policy at the four state universities and the online institution. This policy had never been discussed with faculty and students prior to the announcement, leading to considerable outrage due to the lack of shared governance.

The lack of consultation horrified students and faculty, prompting them to educate themselves on the implications of automatic textbook billing and to actively oppose the policy. This significant discussion underscores the importance of understanding the context behind these findings. The Student Government Association (SGA) voiced their concerns, and students organized a petition against the policy, which garnered over 1,200 signatures1. Local news outlets also covered the story.

The shared governance body, including faculty and administration in the University Senate, voted to pass a motion against the policy. Additionally, the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) union passed a resolution opposing automatic enrollment in the automatic textbook billing plan. Students and faculty also contacted their local representatives, the Higher Education and Employment Advancement Committee, and the State’s Senators.

Findings

The three main findings of this survey are:

• Students who participated in the survey spend an average of $95.97 per semester on textbooks at their institution.

• Students do not support an Automatic Textbook Billing policy.

• If an Automatic Textbook Billing policy is implemented, students would prefer an opt-in option.

An Analysis of Student Expenditure on Course Materials in the Spring 2024 Semester

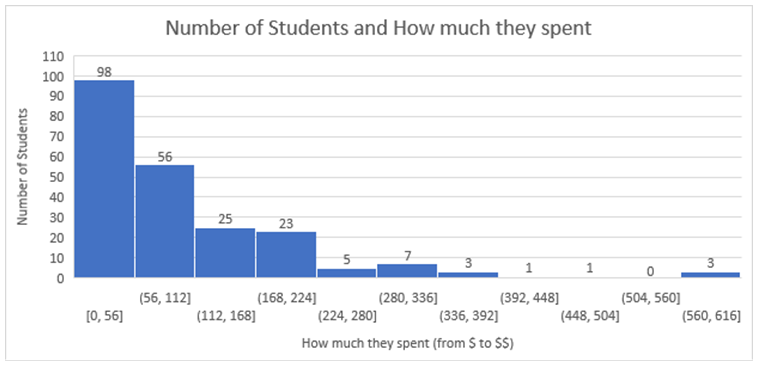

In response to the first research question, which investigated how much money students spent on course materials such as books and software packages during the Spring 2024 semester, survey participants reported an average expenditure of $95.97 on textbooks, with a margin of error of $18.99. It can be stated with 99% confidence that the average student expenditure on textbooks at the institution falls between $77.07 and $114.87, which is significantly below the $281.25 estimated cost under the Automatic Textbook Billing (ATB) program. This latter figure is derived from the ATB cost of $18.75 per credit multiplied by the average number of credits, which is 15.

Survey participants reported needing a median of four books per semester. On average, they acquire their textbooks through various ways: purchasing 1.07 books, renting 1.36 books, and utilizing 1.61 free books. When breaking down the sources of purchased books, students on average buy 0.38 from the campus bookstore, 0.07 directly from the publisher, and 0.064 from Amazon or other online vendors. For rented books, students on average rent 1.04 from the campus bookstore, 0.07 directly from the publisher, and 0.27 from Amazon or other online vendors.

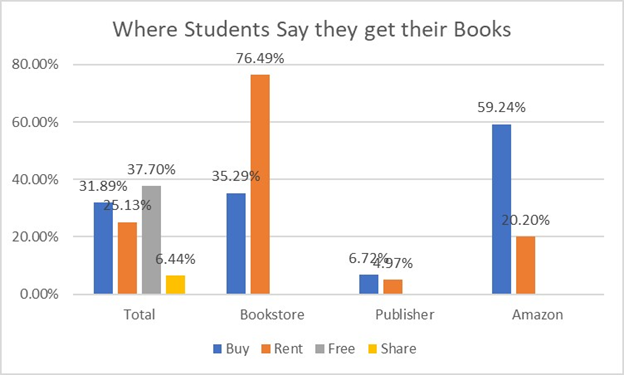

Participants shared how they accessed course materials for the Spring 2024 semester. The data revealed that 31.89% of participants bought their materials, 25.13% rented them, 37.7% accessed them for free, and 6.44% shared with friends and classmates. For purchased books, students obtained 35.29% from the campus bookstore, 6.72% directly from the publisher, and 59.24% from Amazon. For rented books, they acquired 76.49% from the campus bookstore, 4.97% directly from the publisher, and 20.20% from Amazon. The chart below illustrates that while 59.24% of new or used textbooks are sold by online vendors compared to the campus bookstore’s 35.29%, the campus bookstore dominates the rental market, accounting for 76.49% of rentals compared to Amazon’s 20.20% and the publishers' 4.97%.

This breakdown demonstrates that students utilize a diverse range of sources for acessing course materials, balancing between purchasing, renting, and utilizing free resources. The substantial difference between the average actual spending on textbooks ($95.97) and the cost of the Automatic Textbook Billing ($281.25 for 15 credits) program suggests that the mandatory billing system is not the most economical choice for students who participated in this survey.

Rejection of Automatic Textbook Billing Policy

The second research question inquired whether students would support an ATB policy. The overwhelming response against the ATB Policy was surprising, with 216 participants, or 97.3% of the survey respondents, indicating their opposition. This outcome was unexpected, as it was assumed that students enrolled in majors requiring expensive textbooks would be more likely to support such a policy.

By being savvy consumers, most students already have an effective strategy to acquire textbooks at a minimum cost which is below ATB costs, predominantly renting or using free books, students manage to keep their costs significantly lower than what the ATB program would charge for the same rented material. This reinforces their preference for maintaining autonomy over their textbook purchases and likely explains the numerous negative comments about the ATB program. Students’ reliance on more cost-effective options highlights their efforts to manage expenses effectively, further questioning the necessity and benefit of the mandatory ATB policy.

Student Perceptions of Automatic Textbook Billing

Students provided a lot of information about what they were thinking about this policy. Their responses were overwhelmingly angry and expressed numerous objections to Automatic Textbook Billing, describing it as “deceiving,” “unfair,” “intentionally misleading” (42), and “harmful” (197). At the institution, which emphasizes a Liberal Arts Education practically applied with Ethical Reasoning and Critical Thinking as fundamental educational skills, students found Automatic Textbook Billing to be unethical. They argued that the policy infringed on their freedom, sovereignty, and autonomy. Students emphasized their opposition to being forced into a system that undermines their consent—a topic highly discussed in higher education institutions. One student remarked, “If this program is implemented it would be unethical to make it an opt-out program” (176). Others echoed similar sentiments: “Students should have the freedom of choice, regardless of cost” (115). A student stated: “It takes away sovereignty and sense of agency in how students choose their books, the cost of them, and where they order them from. Education is supposed to empower autonomy and sovereignty” (116).

The overall sentiment was summarized by a student who stated, “I think it’s wrong to charge students for textbooks without their consent” (38).

Students also highlighted the burden that Automatic Textbook Billing imposes by forcing them to opt out of a policy to which they did not initially consent. They associated this policy with a strategy to extract more money from them, infringing on their rights as consumers. Many viewed it as an additional financial burden and an unnecessary fee added to their bills without their approval. This sentiment was echoed in their comments, reflecting a sense of frustration and exploitation. For instance, one student argued, “Don’t force that burden on students” (165), while another criticized, “Additional unnecessary fees being blindly added to our bills” (79). The frustration was further captured in remarks like, “This automatic textbook program is stupid. It’s just another way for the university to steal more money from us” (107) and “I feel like a farm animal being milked dry” (133). Another student bluntly stated, “The program is scummy to put it nicely. Feels really anti-consumer” (117).

Students also provided detailed information about their opinions and voiced strong dissatisfaction with the policy of automatically enrolling them in a program without their prior consent. They have emphasized a preference for an opt-in option, which would grant them greater autonomy and control over their participation. The students value having a choice rather than being mandated to comply. This approach resonates with their desire for increased freedom and respect for their individual decisions. One student articulated this sentiment clearly: "I don’t think this idea is bad; however, students should not already be signed up for this. I strongly support an opt in approach with this" (5). Another student commented, "I am not against the option if it was an opt-in process, but being automatically opted in seems very bad" (37).

Additionally, students questioned the purported benefits of forced enrollment, challenging the notion that it serves their best interests. They argued that a truly student-centered policy would be opt-in rather than opt-out, emphasizing transparency and genuine support for student needs. One student remarked, “If this policy really wanted to help students, then it would be an opt-in rather than an opt-out. Making a policy like this that automatically charges students just looks so shady” (146).

Another commented, “If this program truly wants to be a means of helping students, it must be an opt-in system. Without that, it feels as though it is a system meant to get money from students” (97).

Understanding Why Students are so Against Automatic Textbook Billing

Students oppose automatic textbook billing primarily due to their financial acumen; they often find course materials cheaper through alternative sources than those provided by the bookstore. They invest time in searching for the lowest prices rather than opting for convenience at a higher cost. Many students opt to rent or purchase from third-party vendors or publishers, locate free copies online, or share resources with peers. Given the exorbitant costs of textbooks, students have developed diverse strategies to minimize their expenses.

As faculty have observed, first-year students initially face the highest expenses for course materials but quickly learn these money saving methods for subsequent semesters. One student highlighted, "Not all students use textbooks, and there are ways to find free copies online" (30). Another expressed, "Do not implement this. I prefer finding my rented books online for free, even if they are overpriced" (156). A third student emphasized, "I haven't bought a textbook in any semester because Google has every textbook for free. Forcing students to pay a fee where they wouldn't normally is unjustifiable" (162). Reflecting on personal experience, another student shared:

This semester, most of my textbooks cost under $10, with only one large textbook rented at a higher price. Next semester, I anticipate needing even fewer textbooks. Last semester, I found cheaper alternatives outside the bookstore, often at vendors, and accessed helpful audiobooks from the library, all free. An Automatic Textbook Billing policy would be unnecessary and, in cases like mine, detrimental (197).

Additionally, concerns were raised about affordability, with one participant noting, "Many students can't afford textbooks and rely on sharing or borrowing from friends" (216).

Some students are in majors that don't require expensive textbooks or any purchased textbooks at all because their faculty members include course materials in Blackboard, the university’s learning management system. Other students, such as those doing internships or independent studies that don't require textbooks, were also extremely angry at the idea of Automatic Textbook Billing. While students recognized that automatic billing might be financially beneficial for some majors, it certainly isn’t for all. One student remarked, “This is stupid. Especially since not every class has a textbook. I personally would not want to pay 6 classes worth of books if only one class needs it” (101). Another student pointed out:

I see how the program may provide an advantage for kids in majors with high book costs. But for kids in majors like Business Administration, I have not yet had to pay more than $281.25 for textbooks in a semester(102).

An art major expressed frustration, stating:

As an art major, they are going to be billing us for nothing. I have never been given a textbook for an art program here or at my previous university and don't believe that any art professor uses a textbook to teach. We will pay these fees and get nothing out of them while also paying lab fees and course fees on top of that for materials we do actually use(126).

Some students also expressed concerns that not every student will be informed of the policy, leading to unintended financial consequences. One student noted, “Most students would not be aware of this additional cost if it were to be implemented” (172).

Another pointed out:

I understand that there may be an email sent out to remind students to opt out, but we are flooded with emails day in and out so it is easy for a student to simply miss an email of such great importance(79).

Additionally, a student suggested “There needs to be an option for opt-in, not opt-out. If someone does not make themselves aware of this new bill add-on, it will be costing them money” (102).

Finally, students voiced their frustration with automatic textbook billing being tied to their tuition, arguing that it exacerbates student debt. One student emphasized, “I think this is a terrible plan and will only increase student debt” (153). Another student echoed this sentiment, declaring, “This program is horrible and only forcing students to further their student debt” (130).

Negative Perception of the University

Despite the fact that Automatic Textbook Billing was a policy decided by the system office of the four state universities and the public online institution of Connecticut, and not by the campus administrators, students expressed significant dissatisfaction with the institution's administration. One student remarked, “I think this is the worst idea that our institution is thinking of” (162). Another noted, “I knew our institution was nervous about money, but I didn't realize it was so bad that they'd hurt the goodwill of their own students” (117). Students voiced concerns about additional fees being added without their input, with one saying:

“If schools including our institution would like students to still be able to come to their institution, there needs to be a stop to additional unnecessary fees being blindly added to our bills” (79).

Further criticism was directed at the university's financial decisions:

If our institution wants more money maybe they should budget better and not invest in a nursing program, and instead focus on the majors that our institution is known for, and are popular. Our institution has been making some terrible financial decisions, and this is a state school. People go here because it's a more affordable option, and adding hundreds of dollars for no reason just to get more profit that isn't going to benefit students is enraging. This whole school administration is trying to cover up the bad decisions being made and it's so aggravating as a student here (34).

Students also accused the administration of failing to communicate with them and faculty first, despite it not being the fault of the administrators. One student stated, “You should have gotten student/ professor opinions prior to agreeing to this” (144). This lack of communication created distrust, leading many students to wonder what other fees they might be unaware of and if there are any ways to opt out. As one student clearly stated:

I have never found a textbook to be useful or necessary to my learning, and many of my peers say the same. Also, I’d like to know what other services I am not agreeing to but can ‘opt out’ of (105).

Support for the Opting-In Option

In response to the third research question, which inquired whether students would prefer an opt-out or opt-in option for an Automatic Textbook Billing (ATB) policy, the findings indicate a clear preference among the student body. A notable majority of 84.23% (187 participants) expressed a preference for an opt-in approach. This suggests that students would rather actively choose to participate in the ATB policy rather than being automatically enrolled with the option to opt out. The strong preference for the opt-in option underscores the importance students place on having control over their participation in such policies, potentially reflecting concerns about autonomy and financial decision-making.

Discussion

The discussion session will focus on the different issues that have emerged.

Students as rational decision-makers

Consumers behave as rational decision-makers who choose the option that maximizes overall satisfaction, according to traditional economic theories. In the case of students, they typically spend the least amount of money on textbooks. The findings suggest that regardless of the overall expense of their major, students will likely evaluate each semester individually and select options that minimize their costs. By doing so, they can allocate the extra money saved towards living expenses or other educational needs. As seen in other national studies, students at our institution are grappling with the rising cost of living. This economic pressure forces them to make rational choices to ensure their well-being.

Student’s Behavior, Behavioral Economic Theory and the Ideology of Common Good

Behavioral economics examines how policies can be crafted to influence choices and achieve desired outcomes. For instance, automatically enrolling employees in retirement plans serves the greater good, as most people tend to stick with the default option. This opt-out system leads to higher participation rates, which is beneficial for employees' future financial security. Similarly, bookstores, publishers, and some administrators argue that automatically enrolling students in an automatic textbook billing system results in the greater good, leading to cheaper books and making this the preferred default option. However, the findings suggest that students who are rational decision-makers prefer an opt-in option, as it provides them with greater freedom to identify the most affordable sources of course materials.

If the default is set to opt-in, students who take no action would not be enrolled in automatic billing, likely resulting in lower participation. This outcome is financially less favorable for bookstores, which prefer an opt-out default as it ensures more students, including those who do not actively opt-out, are automatically enrolled. Survey data revealed that students were more likely to rent from the campus bookstore and purchase from Amazon. Automatic Textbook Billing (ATB) would increase bookstore revenues. Conversely, under an opt in system, it is likely that only students in majors with expensive textbooks or those facing high textbook costs would enroll, thereby reducing bookstore profitability.

At the institution (see Authors*) [17], the cost per credit with automatic billing is high compared to the cheapest option offered by the campus bookstore. Additionally, 70% of courses during the Spring 2024 semester did not require a textbook. This discrepancy explains why students heavily criticize Automatic Textbook Billing; if implemented, they would end up paying a lot of money unnecessarily. The automatic billing system would be particularly burdensome for students enrolled in courses that do not require textbooks, leading to significant financial inefficiencies and dissatisfaction.

Asymmetric Information

Asymmetric information occurs when one party has information that the other party does not which often causes policymakers to intervene. A common example is the used car market, where the seller knows more about the quality of the car than the buyer. This informational advantage can lead to unfair practices, which is why there are laws in place to protect buyers. A similar issue of asymmetric information exists in the realm of textbooks. Not all parties have the same awareness of textbook costs and available options. Students often don't know whether they are in majors that require expensive textbooks, as textbook cost is not usually a criterion for choosing a major. Faculty and administration may also lack this awareness. However, the campus bookstore typically has a better understanding of the situation and stands to benefit from this knowledge, which may explain why campus bookstores are promoting Automatic Textbook Billing to maximize their profits. This research seems to indicate that ATB instead of mitigating the bookstores’ information advantage could instead exacerbate the information asymmetry as it maximizes their profits.

Interestingly, business students are not responding to the survey. This could be because they believe they will benefit from the proposed system, or perhaps due to the asymmetric information they are unaware of any potential disadvantages to these majors. The exact reason for their lack of response is unclear. However, higher education institutions need to do a better job of informing faculty, advisors, and students about the costs of course materials. Faculty, who are responsible for selecting textbooks, must be made aware of the financial burden their choices place on students. Additionally, majors that require numerous expensive books should be encouraged to examine Open Educational Resources (OER) and materials available at the library.

Addressing this asymmetric information is crucial. By ensuring that all stakeholders are well-informed about textbook costs and available alternatives, institutions can make more equitable decisions that benefit students. This involves not only transparency in the costs associated with course materials but also a proactive approach to exploring and promoting cost-effective resources such as OER and library materials.

Recommendations

Contrary to Barnes and Noble's findings about students' opinions regarding the implementation of automatic textbook billing, the findings indicate the opposite. Respondents to the survey did not express happiness but more commonly rage and disbelief that the Automatic Textbook Billing policy was even being considered. Students were extremely angry at the university and administrators for pushing this policy, which was beyond their jurisdiction. The decision to implement automatic textbook billing was made by the system office without consulting students, the primary stakeholders. Their feedback should be taken seriously by any administrator considering such a policy due to the importance of student persistence and retention as well as the need to avoid negative student pushback in the form of petitions, contacting the board of trustees, representatives, and senators, or students choosing to leave the university in protest.

Early consultation by an administration with stakeholders is important, especially students, when considering a policy change that could impact student’s financial well-being. Feedback from students needs to be weighed carefully. Open communication with students, faculty, and other stakeholders is the key to any exploration of any new policy initiative, such as Automatic Textbook Billing, to start with the primary recipients—students and faculty—to ensure the policy meets their needs. Open communication with students and faculty during the exploration and implementation of any automatic textbook billing policy is crucial. Students have the best understanding of what works for them individually and how to meet their needs in the most cost-effective way.

Additionally, while the campus bookstore provides valuable insights into the financial implications for students, its perspective primarily focuses on spending at the campus bookstore, not on purchases made through Amazon, third-party sellers, or directly from publishers. Despite this limitation, the bookstore has a comprehensive understanding of the resources it provides, and this information needs to be shared more broadly across the institution so that all stakeholders can make choices to maximize student’s financial well- being. This information about the relative cost of textbooks by major can allow faculty to reevaluate the source of their required textbooks and students to better understand the true cost of their education.

Ultimately, for policies like Automatic Textbook Billing to succeed, they must be developed in collaboration with those directly affected. By actively involving students and faculty in the decision-making process and maintaining transparent communication, institutions can better address the needs and concerns of their communities while minimizing potential backlash. An alternative to further developing policies like ATB is to place greater emphasis on promoting Open Educational Resources.

Limitations and Conclusion

The newness of the research field posed a limitation, as only a limited amount of peer-reviewed academic literature focused on student perceptions of automatic textbook billing or inclusive access was available. Consequently, the literature review also had to incorporate information from publishers benefiting from these policies, as well as data from organizations supporting institutions that promote student-focused policies.

The survey was conducted at a single institution with a limited sample size, which may not be representative of the broader student population at other institutions in our state and nationally. The overrepresentation of certain demographic groups, such as women or specific racial backgrounds, can skew the results and limit the generalizability of the findings. Future research should aim to include a more balanced and extensive sample to ensure that the insights gained are applicable to a wider range of students and compare the results from the spring semester to the fall semester when there are many more new students on campus acquiring textbooks.

The study focuses on immediate student perceptions and experiences, without considering long-term outcomes and impacts. While understanding current student sentiments is important, it does not provide a complete picture of the long-term effectiveness and sustainability of policies like automatic textbook billing. Future research should employ longitudinal designs to track the evolving perceptions and experiences of students over time, as well as the lasting financial and academic effects of different textbook cost reduction strategies.

In conclusion, as institutions confront the escalating cost of textbooks, they need to achieve a balance between cost efficiency and respecting student autonomy and transparency is paramount. Policies such as automatic textbook billing can potentially yield benefits in certain contexts, yet they require meticulous planning and implementation, incorporating extensive feedback from both students and faculty.

Moving forward, further research should explore a variety of strategies aimed at mitigating the financial burden of costly course materials. These may include leveraging existing library resources, which students already support through their tuition fees, promoting the use of Open Educational Resources (OER), or encouraging faculty to engage in Open Pedagogy by collaboratively creating educational materials with their students.

By actively exploring and adopting these approaches, institutions can foster a more affordable and equitable learning environment while ensuring that the interests and preferences of students and educators are central to decision-making processes regarding academic resources.

Conflicts of interest:

The researcher declares no conflict of interest, and the study received no funding.

References

McGurran, B. (2023, May 29). College tuition inflation: Compare the cost of college over time. Forbes Advisor. View

Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor. (2016). College tuition and fees increase 63 percent since January 2006. The Economics Daily. View

Correa, E., & Bozarth, S. (2023). To eat or to learn? Wagering the price tag of learning: Zero cost textbook degree. Equity in Education & Society, 2(2), 126–137. View

National Association of College Stores. (2023, June 12). NACS student watch report: Course materials spending dropped, increase in digital preference. View

Florida Virtual Campus. (2022). 2022 Student Textbook and Instructional Materials Survey. Tallahassee, FL. View

California Student Aid Commission. (n.d.). 2022-23 student expense budgets. View

Welding, L. (2024, June 11). Average cost of college textbooks: Full statistics. Best Colleges. View

Barnes & Noble College. (2023). Student Pulse. Insights to Drive Student Success. View

Flaherty, C. (2023, April 28). Affordability, accessibility top course materials concerns. Inside Higher Ed. View

Vitez, K. (2020). Automatic Textbooks Billing: An Offer Students Can't Refuse. US PIRG Education Fund. View

DesJardins, S. L., & Toutkoushian, R. K. (2005). Are students really rational? The development of rational thought and its application to student choice. In J. C. Smart (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (Vol. 20). Springer. View

Martinelli, A. (2004). Rational choice and sociology. In J. C. Alexander, G. T. Marx, & C. L. Williams (Eds.), Self, social structure, and beliefs (pp. 82–102). University of California Press. View

Zafirovski, M. (1999). What is really rational choice? Beyond the utilitarian concept of rationality. Current Sociology, 47(1), 47–113. View

Castro, F. G., Kellison, J. G., Boyd, S. J., & Kopak, A. (2010). A methodology for conducting integrative mixed methods research and data analyses. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 4(4), 342–360. View

Povee, K., & Roberts, L. D. (2014). Attitudes toward mixed methods research in psychology: The best of both worlds? International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 18(1), 41–57. View

Divan, A., Ludwig, L., Matthews, K., Motley, P., & Tomljenovic Berube, A. (2017). Survey of research approaches utilized in the scholarship of teaching and learning publications. Teaching & Learning Inquiry, 5(2), Article 3. View

Clifford, M., & Simon, N., (Manuscript Under Review). Increasing student’s expenses on accessing course material: A Case Study on the True Cost Inefficiency of Inclusive Access.