Journal of Comprehensive Social Science Research Volume 3 (2025), Article ID: JCSSR-111

https://doi.org/10.33790/jcssr1100111Review Article

Exploring the African Lineage of Irish and Italian Identities: Historical Connections and Modern Perspectives

Robb Shawe

Department of Critical Infrastructure, Capitol Technology University, Laurel, MD, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Robb Shawe, Department of Critical Infrastructure, Capitol Technology University, Laurel, MD, United States.

Received date: 24th July, 2025

Accepted date: 07th October, 2025

Published date: 09th October, 2025

Citation: Shawe, R., (2025). Exploring the African Lineage of Irish and Italian Identities: Historical Connections and Modern Perspectives. J Comp Soci Scien Res, 3(2): 111.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

This study examines the intersection of claims about African lineage with Irish and Italian identities, integrating genetic, sociohistorical, and cultural evidence within a single analytical framework. This study poses three research questions: (1) What do population-genetic studies show about African admixture in Italy and Ireland, and how do those signals vary across regions and time? (2) How do socio-historical processes—migration, empire, trade, religion, and racialization— shape identity claims about (or against) African ancestry? (3) Can biomedical data on hemoglobinopathies (sickle-cell disease and thalassemia) and malaria selection be coherently interpreted alongside population genetics? Methodologically, I synthesized peer-reviewed population genetics and ancient DNA studies with historical scholarship and diaspora/postcolonial theory [1-3]. The key findings are: (a) measurable North African-linked ancestry is concentrated in Southern Italy and Sicily and reflects long-range Mediterranean connectivity; (b) at a population level, Ireland shows minimal sub-Saharan African admixture, though modern migration has increased the number of Irish residents of African descent and the local clinical relevance of SCD; and (c) biomedical patterns (SCD and β‑thalassemia) track malaria ecology and mobility rather than any simple, homogeneous 'African descent' for whole national populations. The study advocates for the careful use of genetic evidence, alignment with sociohistorical interpretation, and the avoidance of essentialist claims.

Keywords: African DNA, African Heritage, Irish DNA, Perspective, Italian DNA, Italian Perspective, Culture, Migration, Diaspora, Colonial Struggles, Western European Influence, Social Cohesion, Inclusivity, Identity, Diversity, Cultural Dialogue

Introduction

The question of why Irish and Italian communities often deny their historical ties with Africa is rooted in a blend of historical, socio- cultural, and political factors. Both groups have unique identities shaped by their experiences before and after arriving in the United States. Their assimilation was influenced by American values, entrenched racial divisions, and persistent stereotypes. The relationship of both communities with African leadership in their countries of origin also raises questions about the roots of their denial of historical and genetic connections to Africans [4-8].

Research Questions, Theoretical Framework, and Methodology

Research Questions

(1) Where, when, and to what extent do peer-reviewed genetic studies detect African-linked ancestry in Italy and Ireland?

(2) How do such findings align (or misalign) with socio-historical records of mobility, empire, and trade?

(3) What is the relationship between hemoglobinopathies—whose distributions reflect malaria selection—and identity claims in Ireland and Italy today?

Theoretical Framework

By drawing on diaspora and postcolonial theory to analyze identity as historically situated and relational rather than fixed, this analysis incorporates key interlocutors such as Stuart Hall regarding cultural identity and diaspora, Paul Gilroy on the Black Atlantic, and Brubaker & Cooper's critique of 'identity' as an analytic category. This framework serves to caution against essentialism and facilitates the interpretation of claims pertaining to 'African lineage' through the perspectives of hybridity, translation, and power.

Methodology

Integrating evidence derived from population genetics, including ancient DNA, along with historical scholarship and clinical epidemiology. I prioritize the use of high-quality, peer-reviewed sources and employ triangulation across disciplines to ensure coherence among genetic signals, documented histories of contact, and contemporary health data.

This study initially examines the historical context of Irish and Italian immigration, as well as their experiences with racial hierarchies. It subsequently explores underestimated African influences in Ireland and Italy, analyzes the evolution of racial stereotypes and identity, discusses scientific evidence concerning genetic connections, and considers aspects of cultural integration, social pressures, and the role of eugenics. Ultimately, the conclusion evaluates the impact of these themes on the denial of African ancestry within these communities.

Historical Context of Irish and Italian Immigration

Irish and Italian immigrants came to America in the 19th and early 20th centuries, driven by economic hardship and seeking better opportunities. The Irish were propelled by the Great Famine, while Italians left due to limited industrial prospects and agricultural struggles [9]. Upon arriving in America, both Irish and Italian immigrants encountered a complex and often unwelcoming social environment. They were perceived as outsiders, and their presence was met with significant prejudice and discrimination. This societal bias was deeply entrenched and manifested in both social attitudes and formal policies, including immigration laws that were enforced with fervor during this period, reflecting the broader American sentiment against the influx of immigrants. Despite these obstacles, Italian Americans in particular undertook concerted efforts to address and alleviate these racial and ethnic barriers. In the 1950s and 1960s, they actively campaigned for immigration reforms aimed at reducing the discriminatory practices hindering their acceptance and integration. These reforms were crucial in reshaping the social landscape, allowing Italian Americans to assert their place in American society and seek equitable treatment [10].

Over time, Irish and Italian immigrants successfully integrated into the American cultural fabric, albeit through a partially Americanized lens. This adaptation process exemplifies the intricate interplay between immigration patterns and cultural identity, emphasizing how individuals and groups must navigate and adjust to new societal structures while preserving their unique heritage. The experiences of the Irish and Italians in America underscore the enduring impact of immigration on cultural identity and the assimilation processes within diverse social contexts.

Societal and Racial Hierarchies in the United States of America

Class and racial disparities posed significant obstacles for Irish and Italian immigrants in the United States. Upon arrival, both groups entered a society structured along strict racial hierarchies, where ethnic minorities were routinely subjected to discrimination [8]. The Irish, though European, often faced intense prejudice due to their religious differences, while Italians suffered from stereotypes that painted them as foreigners resistant to assimilation [9]. Despite these challenges, both groups developed strategies to cope with the existing hierarchies and gradually improved their social standing, though their progress required navigating persistent social attitudes and institutional biases.

Stereotypes played a decisive role in shaping the social perceptions of Irish and Italian immigrants in the United States. The Irish were frequently labeled as 'disorderly,' 'lower class,' or 'criminal,' which created barriers to their acceptance in American society [8]. Italians faced similar challenges, as they were often characterized as inherently violent or unassimilable. These stereotypes were rooted in racist theories about Southern Europeans and contributed to the institutional discrimination both groups experienced. As they attempted to reestablish their identities in a new environment, Irish and Italian immigrants had to balance the expectations of the dominant culture with their traditions, making upward mobility a challenging process.

The persistence of these stereotypes not only affected the social positions of Irish and Italian immigrants but also influenced institutional attitudes toward them. Discriminatory beliefs shaped their economic prospects and reinforced barriers to integration. As a result, both groups were forced to operate within the boundaries set by these negative perceptions while striving to maintain elements of their original cultures.

Socio-Economic Challenges in the New World

Both Irish and Italian immigrants were primarily confined to poorly paid, low-skilled, and often dangerous jobs due to widespread discrimination [9]. The buildings where both communities lived were often dilapidated compared to other neighborhoods, and immigrants frequently lacked access to basic facilities and services [10]. Despite these hardships, the drive for socio-economic mobility led to the formation of labor unions and culturally distinctive neighborhoods that aided their integration into American society.

Additionally, the socio-economic conditions encountered by Irish and Italian immigrants involved complications surrounding the industries and labor markets in which the immigrants were involved. Irish immigrants primarily participated in labor markets associated with construction, railroads, and dock labor, typically in unsafe conditions where discrimination limited their access to better-paying careers [9]. The Italian labor force was more seasonal, with employment concentrated in agriculture (from farm to factory) and the emergence of new factories in the United States, where low-skilled and low-wage work was prevalent. This reflected the discrimination and economic competition for available positions in an already uncertain market [10]. Italian Catholic churches promoted community development, but this had varying impacts on the developmental outcomes for the immigrant group; in some cases, church activities had a negative impact on the educational progress of certain immigrant families across generations [11]. These socio economic roles that resulted from employment-market availability due to discrimination served as a continuous line of reasoning for the Irish and Italians working towards integration into the economic America, furthering the challenges to both mobility and acceptance experienced by these immigrant groups.

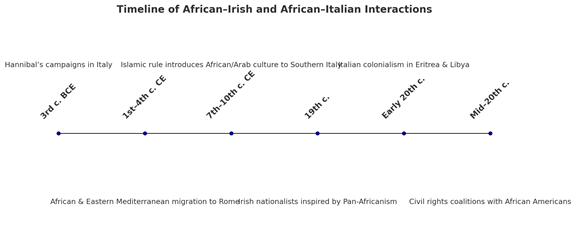

Having outlined the historical context and challenges of Irish and Italian immigration, it is now essential to consider the overlooked connections these groups share with African leadership and influence (see Figure 1). This next section explores how colonial histories and transnational relationships have shaped both communities on a global scale.

Overlooked Historical Connections

Mainstream historical narratives often overlook the significant ideological exchanges between Irish, Italian, and African movements, particularly their shared anti-imperialist sentiments. During their colonial struggles, the Irish forged pivotal alliances with African leaders, contributing to a shared anti-colonial ideology. These connections strengthened resistance efforts against imperial domination and influenced national identity. However, many popular historical accounts tend to gloss over or ignore these connections, prioritizing a more insular focus on internal conflicts, such as the partition that emerged prominently in the history of the Irish Republic. Such narratives often fail to consider the significant ideological exchanges that occurred as Ireland drew inspiration from a larger, global dialogue on resistance and sovereignty, in particular, embracing the ideals of Pan-Africanism championed by African leaders. This shared ideological heritage influenced Ireland's perspective on imperialism and national identity.

Similarly, Italy's historical interactions with Africa are rooted in its imperial ambitions as the nation sought to establish its colonies on the continent of Africa. Despite their colonial aspirations, Italian history also reflects a more nuanced legacy, one that extends beyond political and military endeavors to encompass cultural exchanges and interactions. The Italians, in their pursuit of empire, left behind a complex social legacy, fostering a certain mutual respect and acknowledging the profound impact that African societies had on shaping Italian political, cultural, and social landscapes. This has led historians to explore not only the direct implications of imperialism but also the more subtle cultural influences that lingered long after overt political ambitions had faded.

These intertwined narratives of Ireland and Italy highlight the importance of recognizing the complex and often overlooked influences of African leadership within broader histories of colonialism and imperialism, underscoring the need for a more inclusive analysis that acknowledges these global intersections.

African Leadership and Influences in Irish History

Africa, as a region, has had a profound influence on specific aspects of Ireland's history and the Irish identity. The similarity in anti-imperial movements in Ireland and various African nations highlights a relationship that is often excluded from popular discourse [12]. As the Irish independence movement against imperialism unfolded, intellectuals and leaders within the movement drew inspiration from African anti-colonial movements and their leadership. The ideas exchanged in both directions created a transnational experience, and the trajectory through which Ireland gained independence, implemented its ideas, and established itself as a nation was influenced by such exchanges [13]. Therefore, such analyses are important not only for revealing the complexities of Ireland's political history but also for demonstrating the global and interconnected nature of historical themes concerning colonization and resistance.

Beyond the ideological impact, particular African leaders also left their mark on the historical narrative of Ireland. One example is Kwame Nkrumah. The Ghanaian leader's approach to independence was used as a model for Irish leaders fighting British imperialism. Notably, "Nkrumah's use of mass mobilization alongside nonviolent protests to demand Ghanaian independence" was an inspiring learning for the Irish fighters, paving the way to ultimate success [14]. The African leaders' connection to the Irish opposition's approach to colonialism was also asserted through various events regarding their shared leaders, such as parallels in conferences, meetings on self-determination, and colonial resistance strategies among them. Therefore, these assertions, echoing the mutual-transnational relations of African and Irish resistance, can be considered evidence for the connection between Ireland's dismantling of colonialism and the overall experience, highlighting the shared past of colonial resistance while enriching the narrative of anti-imperialist solidarity.

African Leadership and Influences in Italian History

African influence is evident in Italian architecture, especially in the south, and in the enduring legacy of figures such as Hannibal Barca [15]. The development of political thought in the Italian government was also shaped in part by African leaders' resistance to colonization. These relationships have challenged Eurocentric narratives and contributed to the formation of Italian identity.

Similarly, the history of significant African figures has significantly impacted Italy's perception of its political and cultural history. The most significant figure is General Hannibal Barca of Carthage, who employed his military tactics during the Punic Wars, forging and still influencing Italian military strategy and cultural identity. The above mentioned historical details illustrate the interconnectedness of our history. The trans-Mediterranean connections enriched Italian politics and culture, which affected geopolitical transformations. North African governance during the period of Islamic rule in Southern Italy also influenced intellectual and architectural achievements, which were crucial to unification and the formation of Italy as a nation-state [15]. These details helped to understand complex interconnected processes in African and Italian history. The importance of such relationships and their components challenged Eurocentrism, helping to understand the complex structures and components that shaped Italy's identity in the modern world.

While the histories of colonialism and African influence are significant, how Irish and Italian communities formed their racial identities and responded to stereotypes in America are equally crucial. The following section examines how these communities navigated social boundaries and constructed their identities in response to shifting racial dynamics.

Racial Identities and Stereotypes

The formation of racial identity for both Irish and Italian immigrant groups in America during the late 19th and early 20th centuries was shaped by prevailing stereotypes and prejudices. Both groups faced the challenge of navigating a society deeply entrenched in racial hierarchies, leading the Irish to align themselves more closely with whiteness and distance themselves from African Americans. At the same time, Italians countered stereotypes by adopting Anglo-Saxon behaviors to gain acceptance [7]. These efforts reflected broader attempts to secure a place within the American racial hierarchy and achieve societal acceptance.

Ultimately, the racial identities of both Irish and Italian Americans were deeply influenced by the racial mechanisms that valued lighter skin tone and adherence to Anglo-Saxon norms. These mechanisms enforced a system where proximity to whiteness often determined one's social standing and acceptance within society, making the quest for racial identity an ongoing struggle heavily dictated by the dynamics of race and power.

Development of Racial Stereotypes

Literature and media reinforced stereotypes of Irish and Italian immigrants, perpetuating their marginalization in American society [8]. Irishness was constructed as both inside and outside the realm of racial whiteness [7], while Italians faced constant exposure to group stereotypes asserting their otherness. These stereotypes, rooted in racist theories, complicated both groups' responses to their African lineage.

The construction of racial stereotypes on Irish and Italian immigrants was indeed heavily dependent on their representation. The portrayal of Irish people as drunken and disorderly and of Italians as either organized crime bosses or as strange outsiders repeated the stereotypes that housed Irish and Italian immigrants within an aligned hierarchy. These stereotypes were propagated in literature and film, encouraging a tight racial hierarchy that called for the peculiarity of either group's ethnicity [8].

The portrayal of Irish and Italian immigrants in literature and the media continued to enforce the stereotypes that had been established before, and it also legitimized their use by society, making it hard for the groups to create a separate identity unfettered by their oppressive confines. The role that media played in perpetuating stereotypes highlights their power in strengthening racial structures and dynamics across a defined society as they echoed institutional modes of racism within literature and art. The media's portrayal of the Irish and Italian immigrants further accentuated their distancing from an African heritage and helped them reconcile their cultural rift through the construction of identity [8].

Impact on Perceptions of African Ancestry

Stereotypes associated with Irish and Italian immigrants regarding African roots have had a long-lasting impact on community perceptions. Both groups experienced stigma that resulted in anxiety about being associated with African identity, leading to the denial of their African ancestry [7]. For the Irish, this denial was a strategy to gain political recognition and favor with white supremacy, while Italians faced similar pressures, resulting in identity issues that persisted across generations [9]. The dual need to fit into dominant white communities and avoid exclusion shaped how both communities internally and externally negotiated their identities.

Building on the discussion of racial identity, it is important to address the genetic and scientific evidence that further complicates traditional narratives. The following section investigates genetic links and shared heritage, challenging common assumptions about racial boundaries.

Genetic Evidence

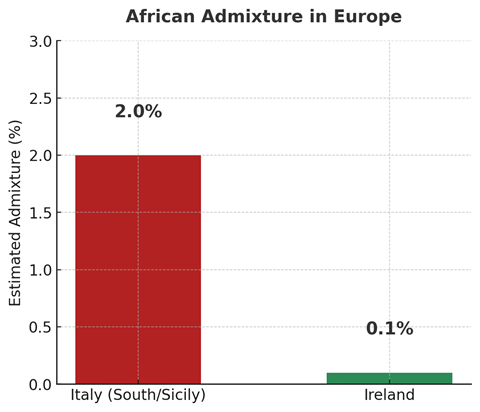

Italy: Southern and Sicilian Patterns

• Multiple lines of evidence suggest long-standing connections between the Afro-Mediterranean regions in Southern Italy and Sicily.

• Genome-wide studies detect ~1–3% North/West African admixture on average in southern Europeans, dated to late antiquity and early medieval times [16].

• Ancient DNA from Imperial Rome confirms the influx of individuals from the Eastern Mediterranean and North Africa, consistent with Rome's cosmopolitan demography [17].

• Uniparental markers reinforce this pattern: Y-chromosome haplogroup E-M81, characteristic of Northwest Africa, occurs at low frequencies in Sicily and mainland Italy, suggesting male-mediated gene flow [18,19].

• Other E1b1b lineages, such as E-M78/E-V13, trace additional routes from the Balkans and Eastern Mediterranean [20].

• Biomedical data align with these findings: The distribution of β-thalassemia and the presence, at low but non‑trivial frequencies, of the sickle-cell trait in Sicily and southern Italy mirror the historical ecology of malaria.

• Clinical surveys confirm that most cases of sickle-cell disease (SCD) in Italy are concentrated in these southern regions [21].

• Complementary evidence comes from livestock: Sicilian and Podolian-lineage cattle breeds show introgression from African and Indic sources, attesting to sustained trans-Mediterranean exchange of animals alongside human movement [22].

• While livestock cannot be used as direct proxies for human ancestry, they corroborate the same maritime networks that facilitated human genetic exchange.

Ireland: Continuity and Recent Shifts

• In contrast, Irish genetic patterns emphasize continuity with Western and Insular Europe (see Figure 2).

• Ancient and modern genomes reveal three major ancestry components: Mesolithic hunter-gatherers, Neolithic Anatolian farmers, and Bronze Age Steppe herders, with minimal evidence of African admixture [23,24].

• Fine-scale analyses reveal subtle regional differences across Ireland and Britain, but no significant contribution from sub Saharan Africa before the modern era [25].

• Clinically, sickle-cell disease was historically absent in Ireland.

• The rising prevalence since the 2000s reflects recent migration and the growth of Irish residents of African descent, rather than deep population inheritance [26,27].

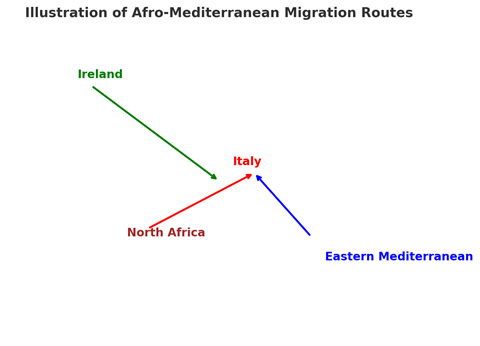

• These Afro-Mediterranean corridors are depicted in Figure 3.

Haemoglobinopathies and Malaria Ecology

The contrast between Italy and Ireland is evident in biomedical patterns. In the Mediterranean basin, malaria historically selected for β-thalassemia alleles and, in specific regions, for the sickle‑cell variant. Italy's modern clinical landscape reflects this ecological legacy. Ireland, which lacks endemic malaria, exhibits SCD almost exclusively among recent migrant populations. These patterns demonstrate that disease distributions track ecology and mobility, not simplified categories of "African descent."

Livestock Genetics as Contextual Evidence

While not evidence of human ancestry, genetic studies of Italian cattle highlight African taurine and indicine contributions in southern and insular breeds. These findings independently confirm the corridors of exchange across the Mediterranean that also shaped human population histories [22]. Taken together, the human and non human genetic data align with archaeological and historical records of sustained connectivity.

Note: Inference Limits

Genetic evidence must be interpreted with caution. Haplogroups trace only paternal or maternal lines; haemoglobinopathies reflect localized ecological pressures; and livestock introgression demonstrates ecological networks, not direct human descent. Population-level averages cannot substitute for individual ancestry. For this reason, genetic signals are best understood probabilistically and contextually, integrated with socio-historical data rather than framed as deterministic proof.

Interpretation

The evidence reveals a spectrum of Afro-European connectivity. Southern Italians and Sicilians exhibit modest but consistent African-linked signals across multiple genetic markers, ecological contexts, and historical layers. Ireland, by contrast, exhibits slight African admixture at the population scale, with most African lineage emerging through recent migration and social networks rather than deep genetic inheritance.

This synthesis highlights a central argument of the study: identity is shaped as much by historical contact, ecology, and political solidarity as it is by genetics. Italian connections illustrate enduring Afro Mediterranean exchanges; Irish connections highlight cultural and political solidarities that transcend minimal biological admixture.

Overview

Genetic research indicates long-standing, multidirectional gene flow between Africa and southern Europe, with detectable signals in Italy and far smaller, often negligible signals in Ireland. These patterns reflect geography (the Mediterranean as a 'bridge'), imperial and maritime networks (Phoenician, Roman, Byzantine, Arab, Norman), and selection pressures linked to malaria. Crucially, genetic ancestry is distributed along clines and varies by region; no single population is exclusively 'of' any continent.

Multiple lines of evidence show African-related ancestry in parts of Italy, especially the south and Sicily:

• Genome-wide studies have detected minor North/West African admixture in southern Europeans, typically around 1–3% on average, dating back to late antiquity/early medieval times [16].

• Ancient DNA from Imperial Rome reveals influxes from the Eastern Mediterranean and North Africa, consistent with Rome's cosmopolitan demographic [17].

Uniparental Markers reflect these Connections:

• Y-chromosome haplogroup E-M81—characteristic of North-West Africa—occurs at low frequencies in Sicily/ continental Italy, indicating episodes of North African male-mediated gene flow [18,19]. Other E1b1b lineages (e.g., E-M78/E-V13), common in the Balkans and eastern Mediterranean, also appear in Italy via complex Mediterranean routes [20].

Haemoglobinopathies and Malaria Selection:

• The distribution of hemoglobin disorders (notably β‑thalassemia) and the presence—at low but non-trivial frequencies—of sickle-cell trait in Sicily and parts of southern Italy track historical malaria ecology and gene flow; contemporary clinical data show that SCD cases in Italy remain concentrated in Sicily and the south [21].

Corroboration from livestock genetics:

• Genomic analyses of Italian cattle—especially those of Sicilian and Podolian-lineage breeds—reveal non-European influences, including African and Indic introgression, which aligns with the known trans-Mediterranean exchange of animals and people [22].

• These livestock patterns do not directly prove human ancestry, but they independently attest to sustained Afro-Mediterranean connectivity along the same corridors used by humans.

Irish Signals of African-Related Ancestry in Ireland: Comparatively Limited

• Ancient and modern genomes from Ireland highlight continuity with Atlantic/Insular Europe, shaped by three major components: Mesolithic hunter-gatherers, Neolithic Anatolian farmers, and Bronze Age Steppe ancestry, without strong African admixture signatures [23,24].

• Fine-scale studies of Britain and Ireland reveal subtle regional structures, but there is little evidence of a substantial non European influx prior to the modern era [25].

• Clinically, sickle-cell disease was historically rare in Ireland; the rising case numbers since the 2000s largely reflect recent migration and the arrival of new Irish of African descent, rather than deep population-wide inheritance [27,28].

• Nonetheless, Europe-wide analyses show trace African ancestry in many populations, usually declining with distance from the Mediterranean [16].

• Given Ireland's position at the northwest edge of Europe, any older African gene flow would be expected to be minimal at the population level—though individual and local exceptions can occur.

Interpretation

The evidence supports a spectrum: southern Italians/Sicilians show clearer African-related genetic signals (although at a low percentage, consistent across methods), whereas present-day Irish populations generally exhibit very low levels at the population scale. This does not negate the potent cultural and political solidarities linking Irish communities to African and African diasporic histories; it clarifies that, biologically, Italian connections tend to be stronger and more localized in the south and islands, while Irish connections are weaker and often more recent. Framing ancestry probabilistically—rather than as essentialist categories—aligns the genetic record with the socio-historical narratives developed in this article.

Note: Inference Limits

Haplogroups and disease alleles trace only parts of ancestry (paternal, maternal, or specific loci) and should be interpreted in conjunction with genome-wide data and historical context. Livestock genetics corroborate corridors of human movement but cannot substitute for direct human DNA or autosomal studies. Irish et al. [29] demonstrate that dental nonmetric traits correlate with neutral genomic distances at continental scales; however, the study does not assert direct links to Irish/Italian/African ancestry. Accordingly, this manuscript cites Irish et al. [29] solely to support the methodological point about proxy measures rather than as evidence of direct ancestry. Nonmetric dental characteristics and genetic markers provide evidence of shared ancestry, and studies of cattle breeds further support the presence of African genetic material in Italian populations [22].

Scientific research demonstrates a definitive correlation between nonmetric dental characteristics and genetic distance, revealing deep-rooted connections that defy traditional racial categorizations [29]. Studies have also revealed genetic links between African, Irish, and Italian populations, with evidence from cattle breeds supporting the presence of African genetic material in Italian populations [22]. These findings challenge the concept of exclusive ethnic identities and point to a more interconnected heritage.

This body of evidence advocates for the acknowledgment of both genetic and cultural evidence as crucial components in validating the historical interconnectedness of these populations. These findings call for a more nuanced understanding of shared genetic histories that transcend traditional racial divides, providing a deeper insight into how these diverse communities have evolved. As the discussion shifts to cultural integration, it becomes clear that a dynamic interplay of historical, social, and genetic factors continually shapes identity.

Cultural Integration of African Influences

Irish and Italian cultures, when examined through the lens of African influences, reveal a tapestry of cultural exchanges that are often overlooked in traditional historical narratives. Italy, with its rich visual culture, presents clear examples of African influences in art and architecture. At the same time, Irish music and folk traditions show adaptations that hint at connections to African rhythms and motifs [15]. These integrations foster unity and highlight the intertwined pasts of these diverse cultures.

These interactions between Irish and Italian cultures, influenced by African culture, serve as microcosms that illustrate broader historical dynamics. They invite us to consider the potential for a unified representation of cultural identity. As I turn to the discussion of social pressures and assimilation, it is important to recognize how these pluralistic cultural exchanges intersect with the desire for societal acceptance and the forces that shape group identity in America.

Understanding cultural integration sets the stage for examining the social pressures and assimilation processes that Irish and Italian immigrants faced. The following section examines how these communities negotiated their identities in response to external expectations and the impact of racial theories.

Art and Literature

African motifs in Italian visual culture—such as architectural influences from Islamic North Africa in Southern Italy—demonstrate enduring cultural exchanges. Irish literature, particularly postcolonial works, has explored themes of oppression and solidarity that resonate with African struggles against colonialism.

Music and Performance

Rhythmic patterns in Irish folk traditions bear striking resemblances to African musical structures, suggesting cultural borrowing through Atlantic networks. Italian Mediterranean music, likewise, reflects African tonalities and instruments, underscoring centuries of intercultural fusion.

Culinary Traditions

Sicilian cuisine incorporates African-introduced crops and spices, such as citrus and couscous, reflecting its deep-rooted Afro Mediterranean ties. Irish diasporic cuisines, though less directly influenced, display adaptations shaped by contact with African American communities in urban environments. These examples illustrate how heritage is expressed not only through genetics and politics, but also through everyday practices such as art, food, and performance.

Social Pressures and Assimilation

Social factors played a significant role in the integration of Irish and Italian immigrants into American culture. Both groups faced external pressures to conform to American norms; however, the formation of robust ethnic enclaves provided supportive environments for negotiating and maintaining their distinct identities while gradually incorporating American cultural practices. This blend of retaining ethnic customs and embracing new ones enabled a smoother entry into American life and prosperity.

The Italians, to a certain extent influenced by the functions of their Catholic churches, encountered a complex trajectory towards integration. These religious institutions played a crucial role in promoting literacy among Italian children, providing them with the educational foundation that would be advantageous for their future as adults. Nevertheless, this rise in literacy was accompanied by restrictive cultural mores, such as prohibitions against intermarriage outside the Italian community, which presented obstacles to full assimilation and naturalization within American society [11].

Similarly, the Irish faced a challenging journey towards assimilation. They encountered significant resistance rooted in prevailing prejudices against their unique form of Catholicism and perceived differences from Anglo-Saxon norms. Native-born Americans often viewed the Irish with suspicion and were keenly observant of how they adopted American customs and values, particularly those associated with the Anglo-Saxon Protestant majority.

Role of Eugenics and Racial Theories

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, eugenics and racial theories promoted a rigid racial hierarchy, emphasizing racial purity and superiority. These ideologies worked to marginalize Irish and Italian immigrants, positioning them ambiguously within the social order and challenging their ethnic identities [7].

The adaptable application of racial theories resulted in the social standing of Irish and Italian immigrants varying according to prevailing societal attitudes. At times, they were regarded as white and capable of assimilation, while at other times, their supposed racial shortcomings were accentuated. As eugenics-based theories gained prominence, these groups were frequently portrayed as racially degenerate relative to the Anglo-Saxon majority, thereby complicating their endeavors to preserve a unique cultural identity and rendering societal integration an arduous process [30].

Discussion: Integrating Genetic and Socio-Historical Evidence

The evidence suggests a geographically graded pattern of African-related ancestry in Europe that corresponds with historical patterns of connectivity. Southern Italy and Sicily demonstrate modest yet consistent signals from North/West Africa and the eastern Mediterranean across various lines of analysis, including genome-wide data, uniparental markers, and haemoglobinopathies. Conversely, Ireland exhibits minimal population-level signals. These biological findings are consistent with factors such as proximity to the Mediterranean, imperial routes, malaria ecology, and historical records of mobility.

Urban Positionality and Black Community Identification: Baltimore, Boston, New York City, and Philadelphia

The determination of identity membership extends beyond genetic factors to include negotiation through ancestry, kinship, neighborhood socialization, political allegiance, and lived experiences. In cities across the United States, such as Baltimore, Boston, New York City, and Philadelphia, some individuals of Irish or Italian descent perceive themselves as members of the Black community—due to mixed African and European ancestry; upbringing in predominantly Black neighborhoods and kin networks; marital interconnections; or adoption of a political and cultural identification rooted in anti-racist solidarity. Conversely, many in suburban environments emphasize whiteness, distance themselves from Blackness, or deny any Black heritage. This contrast exemplifies how racial and ethnic boundaries are constructed and redefined through quotidian 'boundary work,' institutional incentives, and place-based histories.

The analysis of urban identity negotiation in Baltimore, Boston, New York City, and Philadelphia can be strengthened with the addition of expanded case studies. In New York City, for instance, Irish and Italian parishes bordering Black neighborhoods facilitated both solidarities and conflicts, as intermarriage and labor alliances coexisted with efforts to maintain boundaries. In Boston, while the busing crisis illuminated ethnic-racial conflict, working-class coalitions between Irish and African Americans demonstrated the potential for shared struggles.

Philadelphia offers another case of political coalition-building, where civil rights activism intersected with white ethnic politics in parishes and labor unions. Baltimore, with its proximity to Little Italy and historically Black neighborhoods, provides an instructive example of daily contact shaping interracial solidarities and tensions.

Suburban dynamics further complicate these narratives. As Irish and Italian families moved from urban cores to suburbs, symbolic ethnicity increasingly substituted for lived multiculturalism. This shift underscores how geography influences identity: urban environments have fostered intergroup negotiation, while suburbanization has often reinforced whiteness and separation.

Baltimore

The proximity between Little Italy, historically recognized as an Italian enclave, and neighboring Black neighborhoods facilitated frequent daily interactions within docks, parishes, and public schools. These environments fostered intermarriage, interracial solidarities, and also exerted pressures to conform to white ethnic respectability. Consequently, there exists intra-family variation: some relatives identify as Black, based on ancestry and community affiliation, whereas others deny such identification.

Mechanisms behind divergence. First, 'ethnic options' permit many white ethnics to express Irishness or Italianisms as a symbolic, low-cost identity, whereas Blackness in the United States is more consistently racialized and subject to surveillance. Second, suburbanization and social mobility diminish intergroup contact and increase incentives to emphasize whiteness. Third, U.S. rules of descent—ranging from the 'one-drop' norm to contemporary multiracial categories—both facilitate and limit identification with the Black community. Fourth, local institutions such as parishes, unions, and neighborhood associations serve to mediate belonging and boundary-setting across generations.

Boston

While the busing crisis rendered ethnic–racial conflict visible, Irish Boston also fostered currents of anti-racist activism and labor based coalitions. Urban Irish individuals who resided, worked, and organized alongside Black Bostonians occasionally embraced solidaristic identities; conversely, those who migrated to suburban areas often shifted towards 'white' symbolic ethnicity and boundary maintenance, supported by property regimes, educational institutions, and geographical separation.

New York City

In multiethnic districts such as East Harlem, Harlem, specific sectors of Brooklyn, and the Bronx, Irish and Italian Catholic parishes, labor unions, and neighborhoods have traditionally bordered Black and Afro-Caribbean communities. Shared workplaces, educational institutions, and civic organizations have historically fostered both conflict and solidarity. Some individuals with Irish, Italian, or African ancestry, or those socialized within Black neighborhoods, identify with the Black community; others utilize their white-ethnic status to distinguish themselves from Blackness in pursuit of upward mobility.

Philadelphia

Civil rights activism in the urban North promoted the formation of Black-ethnic coalitions within workplaces, parishes, and ward politics. Concurrently, boundary enforcement by white ethnic groups also intensified in certain districts. Individuals of mixed Irish/Italian and African descent, or those with extensive socialization within Black neighborhoods, often identify with the Black community; however, some oppose such identification as they relocate to suburban environments that favor assimilation into whiteness.

Interpretive Caution

Claims regarding 'genetic heritage' should not be accepted at face value: verification of individual ancestry requires genomic data, and signals at the population level vary by region (more pronounced in Southern Italy and Sicily; minimal at the Irish population scale). In practice, identification with the Black community in these cities is often based less on genetics and more on kinship, neighborhood socialization, intermarriage, and political solidarity. This interpretation is consistent with diaspora and postcolonial theory, which posits that identity is relational, historically situated, and contested rather than fixed.

Illustrative Vignette A (New York City)

A respondent of mixed Irish and Afro-Caribbean ancestry, raised in a Brooklyn parish and public schools, describes "being read" as Black by peers and teachers and participating in Black student unions and civic groups. Her Irish surname and kin networks were sources of pride, but they did not outweigh the everyday racialization that she experienced. Community belonging—encompassing church life, neighborhood mentors, and political organizing—made identification with the Black community both intuitive and strategic, even as she maintained her Irish family identity.

Illustrative Vignette B (Boston)

A multigenerational Italian American family relocated from the North End to a suburban town in the 1980s. Relatives recount oral history hints of African ancestry from Sicily, but emphasize "being Italian" and, increasingly, "being white." Physical distance from the city, school zoning, and property ownership reinforced a boundary between their symbolic ethnicity and the Black neighborhoods where earlier generations had worked. Younger members express curiosity about family stories but feel social pressure to deny any Black heritage in suburban peer settings.

Crucially, identity formation in the Irish case remains profoundly shaped by socio-political solidarities with African anti-colonial movements, despite the limited presence of African genetic signals at the population level. This validates a non-essentialist approach: culture and politics can produce durable affiliations and shared imaginaries even where genetic exchange is minimal. Conversely, the Italian/Sicilian case demonstrates how repeated trans-Mediterranean contacts left modest but detectable genetic traces that complement cultural exchanges. On the 'cattle' evidence, genomic introgression observed in Italian breeds (i.e., Sicilian and Podolian-lineage cattle) provides independent confirmation of long-term Afro-Mediterranean exchange along the same maritime and overland corridors humans used. While not direct evidence of human ancestry, these signals triangulate with human genetic and historical data, strengthening the inference of sustained connectivity.

Together, these findings integrate genetics with postcolonial and diaspora theories, demonstrating that admixture and mobility complicate fixed ethnic boundaries. At the same time, solidarities and racial hierarchies shape whether communities acknowledge or deny their African ties. Both biological and cultural linkages inform contemporary debates on identity and belonging.

Conclusion

The ongoing impact of historical, social, and scientific factors significantly shapes current discussions surrounding identity, belonging, and the acknowledgment of African heritage in Irish and Italian communities. Historically, various migrations and cultural exchanges have left indelible marks on these communities, contributing to the complex mosaic of identities that exist today. For instance, the migration patterns over centuries have introduced diverse cultural elements, leading to the unique blend of traditions found within Irish and Italian cultures.

As the urban analysis ("Urban positionality and Black community identification") demonstrates, membership in the Black community among people of Irish and Italian descent in cities such as Baltimore, Boston, New York City, and Philadelphia is negotiated through kinship, neighborhood socialization, intermarriage, and political solidarity as much as—often more than—through genetics. This complements our genetic synthesis (especially the findings from Southern Italy and Sicily) and underscores that ancestry, history, and lived experience co-produce identity.

Social factors also play a crucial role in shaping modern conversations about heritage and identity. The evolving nature of social norms and increased awareness of multiculturalism push these communities to reexamine and sometimes redefine what it means to belong. As global interactions increase, people from all backgrounds find themselves questioning traditional notions of identity, leading to richer, more inclusive definitions that recognize diverse ancestries. Meanwhile, scientific advancements, particularly in the fields of genetics and anthropology, provide new insights into the interconnectedness of diverse populations. DNA testing and studies in population genetics reveal evidence of mixed ancestry, prompting many within these communities to reassess their understanding of their lineage and cultural heritage. This scientific evidence supports a more nuanced understanding of how African heritage is intertwined with Irish and Italian identities, fostering a broader sense of belonging and acceptance.

Together, these historical, social, and scientific factors create a dynamic framework that continues to influence and enrich the dialogues regarding identity and the recognition of African heritage in these communities, encouraging ongoing exploration and celebration of their multifaceted cultural landscapes.

Future Research

Future research should build on this interdisciplinary approach by expanding both scope and method. Genome-wide studies across diverse European regions can refine understandings of African admixture patterns, while ancient DNA studies continue to reconstruct long-term population movements. Ethnographic research with Afro Irish and Afro-Italian communities can provide insight into the lived experiences of individuals with hybrid identities, complementing the genetic record with cultural and political narratives.

Comparative studies beyond the United States are also vital. In Canada and Australia, for example, Irish and Italian diasporas navigate African heritage in different political and racial contexts, offering important contrasts to U.S.-based dynamics. Ultimately, cross-disciplinary collaborations—bringing together geneticists, historians, anthropologists, and cultural theorists—are crucial for developing a comprehensive understanding of identity, mobility, and heritage.

Competing Interest:

The authors of this research declare no competing interest regarding this study.

References

Hall, S. (1990). Cultural Identity and Diaspora. In J. Rutherford (Ed.), Identity: Community, Culture, Difference (pp. 222–237). London: Lawrence & Wishart. View

Gilroy, P. (1993). The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. Harvard University Press. View

Brubaker, R., & Cooper, F. (2000). Beyond 'Identity'. Theory and Society, 29(1), 1–47. View

Ignatiev, N. (1995). How the Irish became white. New York: Routledge. View

Jacobson, M. F. (1998). Whiteness of a different color: European immigrants and the alchemy of race. Harvard University Press. View

Guglielmo, T. A. (2003). White on arrival: Italians, race, color, and power in Chicago, 1890–1945. Oxford University Press. View

O'Malley, P. R. (2023). The Irish and the imagination of race: White supremacy across the Atlantic in the nineteenth century. University of Virginia Press.View

Spickard, P., Beltrán, F., & Hooton, L. (2022). Almost all aliens: Immigration, race, and colonialism in American history and identity. In taylorfrancis.com. Routledge. View

Alba, R. D. (2023). Italian Americans: Into the Twilight of Ethnicity. In Plunkett Lake Press. View

Battisti, D. (2019). Whom we shall welcome: Italian Americans and immigration reform, 1945-1965. View

Gagliarducci, S., & Tabellini, M. (2021). Faith and assimilation: Italian immigrants in the US. Aeaweb.Org. View

McVeigh, R., & Rolston, B. (2023). Ireland, Colonialism, and the Unfinished Revolution. In Haymarket Books. View

O'Leary, B. (2019). A treatise on Northern Ireland, Volume Iii: Consociation and Confederation. In Oxford University Press. View

Lynch, R. J. (2019). The partition of Ireland: 1918–1925. In Cambridge University Press. View

Giuliani, G. (2019). Race, nation, and gender in modern Italy: Intersectional representations in visual culture. In Palgrave Macmillan, London. View

Moorjani, P., et al. (2011). The history of African gene flow into Southern Europeans, Levantines, and Jews. PloS Genetics, 7(4), e1001373. View

Antonio, M. L., et al. (2019). Ancient Rome: A genetic crossroads of Europe and the Mediterranean. Science, 366(6466), eaay6826. View

Semino, O., et al. (2004). Origin, diffusion, and differentiation of Y-chromosome haplogroups E and J: Inferences on the Neolithization of Europe and later migratory events in the Mediterranean area. American Journal of Human Genetics, 74(5), 1023–1034. View

Di Gaetano, C., et al. (2009). Differential Greek and northern African migrations to Sicily are supported by genetic evidence from the Y chromosome. European Journal of Human Genetics, 17(1), 91–99. View

Cruciani, F., et al. (2007). Tracing past human male movements in northern/eastern Africa and western Eurasia: New clues from Y-chromosomal haplogroups E-M78 and J-M12. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 24(6), 1300–1311. View

Colombatti, R., Casale, M., & Russo, G. (2021). Disease burden and quality of life in children with sickle cell disease in Italy: Time to be considered a priority. Italian Journal of Pediatrics, 47, 163. View

Mastrangelo, S., Tolone, M., Ben Jemaa, S., Sottile, G., Di Gerlando, R., Cortés, O., Senczuk, G., Portolano, B., Pilla, F., & Ciani, E. (2020). Refining the genetic structure and relationships of European cattle breeds through meta-analysis of worldwide genomic SNP data, focusing on Italian cattle. Scientific Reports, 10. View

Cassidy, L. M., et al. (2016). Neolithic and Bronze Age migration to Ireland and establishment of the insular Atlantic genome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(2), 368–373. View

Gilbert, E., et al. (2017). The Irish DNA Atlas: Revealing fine‑scale population structure and history in Ireland. Scientific Reports, 7, 17199. View

Leslie, S., et al. (2015). The fine-scale genetic structure of the British population. Nature, 519(7543), 309–314. View

McMahon, C., et al. (2001). The increasing prevalence of childhood sickle-cell disease in Ireland. Irish Journal of Medical Science, 170(2), 116–118. View

Ryan, E., Allen, A., Ngwenya, N., Sheehan, C., Manning, C., Byrne, B., Lynch, C., Regan, C., & Tuohy, E. (2023). Pregnancy outcomes in women with sickle cell disease in Ireland: A retrospective review. Hemasphere,7(Suppl), 20. View

McMahon, C. (2001). Collective rationality and collective reasoning. Cambridge University Press. View

Irish, J. D., Morez, A., Girdland Flink, L., Phillips, E. L. W., & Scott, G. R. (2020). Do dental nonmetric traits actually work as proxies for neutral genomic data? Some answers from continental-and global-level analyses. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 172(3), 347–375. View

Turda, M., & Balogun, B. (2023). Colonialism, eugenics, and 'race in' Central and Eastern Europe. Global Social Challenges Journal, 2(2), 168–178. View