Journal of Information Technology and Integrity Volume 1 (2024), Article ID: JITI-103

https://doi.org/10.33790/jiti1100103Research Article

Diffusion of Mobile Point of Sales among Small Enterprises in a Metropolis in Northeast Nigeria

Samuel Chiedu Utulu1*, Hyelda Dzamar2, Aisha Lami Hammani3,

1,2 Department of Information Systems, School of Information Technology and Computing, American University of Nigeria, Yola, Adamawa State, Nigeria.

3 Department of Entrepreneurship, School of Business and Entrepreneurship, American University of Nigeria, Yola, Adamawa State, Nigeria.

Corresponding Author: Samuel Chiedu Utulu, Ph.D., Assistant Professor, Department of Information Systems, School of Information Technology and Computing, American University of Nigeria, Yola, Adamawa State, Nigeria.

Received date: 19th September, 2024

Accepted date: 18th October, 2024

Published date: 21st October, 2024

Citation: Utulu, S. C., Dzamar, H., & Hammani, A. L., (2024). Diffusion of Mobile Point of Sales among Small Enterprises in a Metropolis in Northeast Nigeria. J Inform Techn Int, 1(1): 103.

Copyright: ©2024, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Abstract

Stakeholders need to understand the factors influencing the diffusion of mobile point of sale (mPOS) among small enterprises in socio-economically unstable developing contexts. Consequently, the study was conducted in a metropolis in Northeast Nigeria given that it provides a good example of a socio-economically unstable developing context. The inductive reasoning and inferring approach, and subtle realist ontology were used to inform the study. The approach and ontology were combined with the methodological and epistemological assumptions postulated in the constructionist grounded theory. The small enterprises and the people studied, namely, small enterprise owners were selected using the purposive, convenience and snowball sampling techniques. The unstructured in depth interview and participatory observation were adopted as the data collection techniques. The thematic data analysis technique was used to analyze the data collected for the study. The study findings show how socio-technical factors influenced mPOS diffusion among small enterprises and how the factors influenced the extent mPOS served as a means and end to sustainable development in the research context. We conclude that new theoretical insights were derived from the study and recommend that more studies be conducted to provide more information on mPOS diffusion and how it promotes sustainable development.

Keywords: Mobile Payment Systems; Diffusion of Point of Sales; Socio-economically Unstable Developing Contexts; Small Enterprises; Capability Approach; Nigeria

1. Introduction

Small enterprises are pivotal to the socio-economic and sustainable development aspirations of countries across the globe [1]. In Nigeria, small enterprises are usually owned by individuals, established based on a capital-base that is between five million and fifty million naira, and are found in most contexts, including, urban, sub-urban and rural areas [2]. This is the reason why small enterprises are pivotal to job creation, citizens’ livelihood and sustainable development [3]. Also, small enterprises are involved in retail sales and serve as the points for distributing products and services produced by large and medium sized enterprises. Small sized ‘departmental’ stores that sell everyday life products including foods and beverages, toiletries, electronics, medications, clothes, etc. are good examples of small enterprises. Small enterprises also deal in bird and poultry farming, general food farming, including fish farming, eatery and catering services, computer and mobile device sales and repair, and rental services. The important thing about small enterprises is that they serve the socio-economic needs of their owners, the personnel who work in them, larger business ventures and the larger society, and consequently, as drivers of sustainable development [4]. Consequently, countries across the globe develop and implement policies to ensure that small enterprises operate at maximum capacity and within enabling socio-technical business environments [5,6].

The mobile point of sale (mPOS) payment initiative evolved as a fallout of the cashless society initiative. The cashless society initiative is a good example of a monetary policy initiative meant to support businesses including, small enterprises. mPOS runs on hardware that combines the capacity of a smartphone or tablet, software applications including cash register applications, and the internet. mPOS enables those conducting financial transactions to make and accept payments virtually irrespective of the physical locations of the banks where their monies are deposited. The mPOS enables small enterprises to adopt payment systems that have the potential to increase payment efficiency and effectiveness for both local and international transactions [7]. Initiatives meant to promote the diffusion of mPOS by small enterprises are beneficial for driving sustainable development through inclusive and productive payment systems. The initiatives have been heralded as helpful in terms of ameliorating the inefficiency and insecurity that characterizes the Nigerian monetary system and those of many other developing countries [8,9]. Aside supporting trailing and accountability, mPOS also enables ongoing efforts to ensure that key stakeholders have access to reliable business financial transaction data. Business financial transaction data enable stakeholders to gain knowledge on how to use policy frameworks to drive the sustainability of small enterprises and enhance their contributions to sustainable development [10-12]. Several benefits of mPOS to small enterprises have been underscored in the extant literature including, accountability, efficient and effective payment systems, cashless transactions and increase in international transactions and foreign exchange earnings [7,13,14].

Data obtained from the Nigerian Interbank Settlement System (NIBSS) that was made public by the NBS (2020) indicate that mobile payment system transactions’ value in Nigeria grew from 3.2 trillion naira in 2019 to 5.7 trillion naira in 2020. One may, therefore, argue that the mobile payment system, a primary part of which is the mPOS, has been accepted by businesses and is also yielding desired benefits. While the growth is desirable, Masihuddin’s et al. [15] position regarding the extent to which transaction data reflects reality sounds like a call for caution. Given Masihuddin and his colleagues’ position, there seems to be a genuine need for a thorough assessment of the realities surrounding the diffusion of mPOS among small enterprises and how this connects with sustainable development. This need is critical considering the outcomes of recent studies conducted in Nigeria on the challenges to the diffusion of mPOS among small and medium sized enterprises. Some of the studies indicate that in reality there are factors that constitute setbacks to mPOS diffusion among small enterprises namely, infrastructure, awareness and security issues [16,17]. Studies conducted in other countries also indicate that despite the benefits of mPOS, that there has been a slow rate of diffusion, particularly among small enterprises [13,18]. Aside indicating the cogency of Masihuddin and collegues’ call for caution, findings in scholarly studies also raise new questions.

Questions about mPOS diffusion derived from the findings of scholarly studies though critical, confront two challenges. The first challenge is that they are more prevalent in socio-economically unstable developing contexts and require a hybrid methodological stance that suits unstable developing contexts. In this study, socio-economically unstable developing contexts are characterized by limited resources, high rates of social conflicts, exclusion, economic instability, unstructured changes in public policies and weak institutions. Another issue is that the studies were driven by existing formal IT adoption/acceptance theories invented in stable socio-economically developed contexts. This study is based on the notion that formal theories may distort scholarly research outcomes by providing the basis for biased assumptions [19]. Consequently, we adopted the inductive research reasoning and inferring approach to study a socio-economically unstable developing context namely, a metropolis in Northeast Nigeria. The inductive research approach runs with the assumption that there is likely to be one new thing to find out about social phenomenon and the logic that conclusions can be inferred from a sample to a population [20]. The study was driven by the following research questions: What factors influence the diffusion of mPOS among small enterprises in the Yola metropolis and how do they influence the extent to which small enterprises are likely to contribute to sustainable development? The study contributes to further understanding of factors that influence the diffusion of mPOS among small enterprises in socio-economically unstable developing contexts and how mPOS diffusion contributes to sustainable development.

2. Literature Review

2.1. IT Adoption/Acceptance Theories and mPOS Diffusion by Small Enterprises

In general findings in the literature show the benefits of small enterprises to society, the benefits small enterprises and other forms of enterprises are likely to derive from mPOS adoption, and the factors that determine mPOS diffusion. The literature as it currently stands, do not contain a profound revelation on how mPOS diffusion may enable small enterprises support sustainable development [21]. Salder et al. [22] for instance, argue that small enterprises are usually the highest in number among all categories of formal business enterprises across the globe. The notion is applicable to Nigeria where micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) constitute about 96% of business enterprises (PWC, 2020). PWC (2020) also reveals that MSMEs contribute about 48% of the national GDP and employ at least 84% of the employed citizens. The socio-economic value of MSMEs informed the growth in the number of studies that assessed the adoption of mPOS among them. Many studies emerged in the literature that reported various factors that influence mPOS adoption [7,13]. However, a critical look at the extant literature reveals that technology adoption/acceptance theories were used to inform many of the studies that addressed mPOS adoption. The theories include the technology acceptance model (TAM) [23], and extended technology acceptance model [24], the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT) [25] and information systems (IS) success theory [26].

Dastan & Gurler [27] for instance, used Davis's [23] technology acceptance model to drive their study and as a result identified perceived ease of use, perceived trust, perceived usefulness and perceived mobility and attitude as the factors that come to bear in the diffusion of mPOS. Many other studies developed mPOS adoption models that indicate that trust and risk are important to its adoption [18,28,29]. Privacy was also identified as the mPOS adoption factor. Scholars are concerned that mPOS use encompasses procedures that expose users to privacy breaches, and unauthorized access to their personal and bank-related data [30,31]. It follows that privacy is related to perceived risks associated with mPOS adoption. Another study that adopts IT adoption/acceptance theories is de Luna et al. [32]. de Luna and his colleagues propose a behavioral model that describes behavioral factors that influence the intention to use mPOS. An interesting revelation in the study is factors that determine the diffusion of mPOS are contextual and cannot be pinned into a globally relevant model. A study done by Chandra et al. [33] used a trust-based model rooted in technology acceptance models, to assess the diffusion of mPOS. In the end, the study listed perceived reputation, perceived opportunism, perceived environmental risks and perceived structural assurance as factors that determine the diffusion of mPOS. It follows that most studies done and reported in the literature were informed by existing technology adoption/ acceptance theories and the sentiments the theories promote. While the contributions of the studies are encouraging, the studies did not provide novel and context-specific explanations.

2.2. Diffusion of Innovation Theory and mPOS Adoption

The diffusion of innovation theory emanated from rural sociology in the 19th Century when researchers sought to understand the social forces that promote the diffusion new agricultural innovations in rural areas in the United States of America [34]. Innovations are technologies and technologies stands for how people creatively do things or complete tasks [35]. There are a variety of theories that have been propounded to explain the diffusion of innovation [36], Rogers’ variation however, is the most popular among them. Rogers [37] argues that diffusion of innovation is a decision of “full use of an innovation as the best course of action available… (p. 177).” He defines diffusion as “the process in which an innovation is communicated thorough certain channels over time among the members of a social system (p. 5).” Similarly, Kinnunen [36] defined diffusion as the “spreading of social or cultural properties from one society or environment to another (p. 431).” Accordingly, there are five key components of innovation diffusion namely, the innovation, adopters, communication channels, time, and social system. In the context of this study, mPOS is the innovation in question. It denotes a technology, that is, a way of completing financial transactions that is expected to be diffused by small enterprises. Consequently, mPOS, small enterprises, oral and IT driven communication channels, the time when mPOS was invented and now, and the socio-economically unstable contexts where banks, financial service providers, small enterprises, and customers implement mPOS based on enshrined norms, cultures and values constitute the components of mPOS diffusion in the study.

Knowledge, persuasion, decision, implementation, and confirmation are the five stages in the innovation diffusion process identified by Rogers [37]. Rogers [37] opines that there are three types of knowledge that come to bear during the knowledge stage. The types of knowledge are awareness knowledge, how-to-knowledge and principles knowledge. Rogers argued that these knowledge types lead to the next stage in the process namely, persuasion when the adopters are either persuaded to or dissuaded from adopting the innovation. The next stage in the process is the decision stage. The stage when adopters decide to adopt the innovation or reject it. Sahin [34] notes that Rogers [37] identifies two types of innovation rejection. The two types are active rejection and passive rejection. Active rejection occurs when innovation adopters reject an innovation after using it for a while. Passive rejection occurs when innovation adopters reject an innovation before trying it out. The next stage in the innovation diffusion process is the implementation stage when adopters put the innovation into actual use. This is followed by the last stage known as the confirmation stage. Contextual issues come into play in the implementation stage. Contextual issues may lead to reinvention, that is, the reconfiguring of the innovations, based on contextual needs, to suit context-specific requirements. The implementation process can go hand-in-hand with the confirmation in a reiterative way. Reiterative confirmation occurs when innovation adopters consult with one another to confirm the benefits and setbacks of an innovation. With the following explanations, innovation diffusion is a socio-technical process embedded in context [34,38,39]. Despite the contextual nature of innovation, many scholars who study mPOS diffusion did not fully address diffusion as a context-specific process. Nandonde’s [40] advice that the diffusion of innovation theory offers scholars good grounds for evaluating the diffusion of mPOS may not make much impact if scholars study innovation factors without considering its contextual nature.

2.3. Capability approach

An obvious limitation in the literature covering mPOS diffusion is the lack of connection between mPOS diffusion and sustainable development. Small enterprises are believed to be critical to sustainable development of socio-economically unstable developing contexts. Despite this, many studies done to assess the diffusion of mPOS by small enterprises did not factor in how mPOS diffusion can come to bear in sustainable development. The scenario is surprising because of the growing body of literature that assesses the connection between IT and sustainable development [41,42] and given desperate calls made by senior scholars for more studies that address IT and development [38,43]. The state of current literature on mPOS diffusion raises two crucial questions. First is if mPOS diffusion by small enterprises constitutes a critical factor of sustainable development. The second is understanding the factors that come to bear on the extent mPOS may contribute to sustainable development. The capability approach proposed by Amartya Sen is a prominent postmodernist development ideology widely used to assess development from a human freedom perspective. As a development theory that is hinged on postmodernist development ideology, capability approach provides notions that negate those propagated in development theories that are based on classical, neo-classical and modernist notions [44,45]. It rejected the welfarism and utilitarianism approach to human development. The capability approach proposes three primary factors that are critical to human development. The factors are namely, inputs, capability set and functioning. While inputs are resources, both natural and man made, capability sets have to do with the freedom required to work unhindered towards achieving set functionings. Functionings are achieved capability sets usually in the forms of an individual life goal [46,47]. The capability approach also proposes two other adjoining factors that come to bear in sustainable development. The adjoining factors are conversion factors, and choice and agency. The capability approach argues that contexts, social arrangements and how individuals are conceptualized in human development are critical to sustainable development [48].

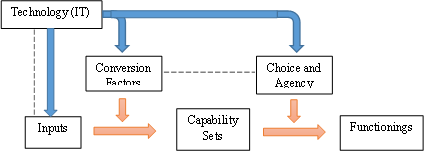

Over the years many scholars have adopted the capability approach to look at sustainable development across diverse social contexts [49,50,51]. Within the development studies circle, the place of IT, within the capability approach framework has been controversial. While some scholars believe that IT should be taken as other inputs [41,52], some other scholars advocate that IT should be treated as a special kind of input [49]. The implication of the later notion is that IT should be accorded characteristics that are similar to that of conversion factors namely, to “amplify, or modify the characteristics of inputs [53].” Haenssgen & Ariana [53] developed a framework that explicates different notions about the place of IT in capability approach. Their framework was an adaptation of Robeyns’ [54] capability approach framework. Haenssgen & Ariana [53] propose three possible cases of how IT can be treated in the capability approach framework. The cases are a) a situation where IT impacts on conversion factors; b) a situation where IT impacts on both conversion factors and choice and agency; and c) a situation where IT impacts on conversion factors, agency and input [53]. We chose to follow the third case namely, the situation where IT impacts conversion factors, agency and input. This is represented in the Figure below.

It follows that in our study we take mPOS as an IT that is different from other in puts given our belief that mPOS is adopted by small enterprises to amplify inputs, conversion factors, and choice and agency. Inputs that are inputted into small enterprises businesses by their owners include money, materials, personnel, strategies and processes. We take it that mPOS are adopted to amply these inputs. The conversion factors are social arrangements including, other types of businesses, service organizations including banks, transportation, and security agencies. Conversion factors are also socio-cultural conditions including, norms, values rules and regulations, cultures, etc. prevalent in the social setups where small business are located. Choice and agency has to do with the extent small enterprise owners could choose and determined, from the diverse ways that are available to implement mPOS, the best possible ways mPOS should be implemented within the business environments where they operate. A further implication of this is the way small enterprise owners are treated, either as passive or active recipients of the mPOS technology.

3. Methodological Assumptions of the Study

The study is based on the inductive reasoning which promotes the notions that: (a) there is always one new thing to learn about any given phenomenon; (b) generalization should be probable and applied to a population based on an observation of a single case in the population and; (c) scientific inquiries should be driven by a priori knowledge [20,55]. The subtle realist ontological stance aligns with the requirements of research studies done with the inductive research approach. The subtle realist ontological stance would have us belief that there is reality out there that is independent of human mind. It went further to argue that the distortions in existing scientific assumptions and methods make the reality difficult to access and studied [56,57]. We took the distortions in existing scientific assumptions and methods to mean the unbridle use of formal theories and the ontological, methodological and epistemological assumptions that they promote and hence, informed our study with a priori knowledge. Therefore, the research process comprises the initial observation we carried out that indicated low diffusion of the mPOS by small enterprises in the study context. This was followed by a more in-depth and structured observation of mPOS diffusion in the study context to gather more data on the factors that determine mPOS diffusion and how it impacts sustainable development. Next, we coined the research question, wrote the introductory part of the paper and developed a study plan. This segment was facilitated by a brief literature review which was done to gain some understanding on what has already been published in the extant literature that are related to the study’s research question. We adopted the enumerative inductive reasoning method, argument from analogy inductive generalization and epistemological stance of the constructionist grounded theory method. The enumerative inductive reasoning allows researchers to develop premises and reach conclusions based on the number of observed cases that align with the premise being investigated and generalize the conclusions to the entire population [58,59]. The epistemological stance of the constructionist grounded theory method allows researchers to carry out preliminary literature review to ascertain the importance of their research questions before they collect data [60,61]. This is given that it will have us belief that researchers should be allowed to consult the literature but should not allow themselves to be unduly influenced by the contents [19]. The preliminary literature review shows that many of the few studies we consulted and the studies the authors cited were driven by technology adoption/acceptance theories. Therefore, we concluded that our choice to adopt the inductive reasoning was in order [62].

Consequently, the next step we followed was to choose appropriate sampling techniques for selecting small enterprises, their owners and the personnel that work in them that participated in the study. The choice of sampling techniques was driven by the subjectivism epistemological assumption of the constructionist grounded theory. The assumption allows for subjectivity namely, researchers’ active involvement in the processes of knowledge construction [19,63]. Consequently, the small enterprises studied were selected using purposive and convenience sampling techniques. Also, the purposive and snowballing sampling techniques were used to select the people who participated in the study. Purposive, convenience and snowballing sampling techniques are subjective techniques [64,65]. Research data were collected through unstructured in-depth interviews and participatory observation. The unstructured in-depth interviews were emergent and conversational discussions between us and the study participants [66]. The element of probing or interrogation that we adopted during the unstructured in-depth interview enabled us to elicit important information about the research problem from study participants [67]. Ten tentative interview questions were used to kick-start each interview session. Each interview session lasted between forty-five minutes and sixty minutes and involved teasing out information relevant to the research question raised in the study. The participatory observation led to observing notice boards and spending time with personnel in offices, and waiting areas and eating places. We also asked questions during the participatory observation and recorded our findings in a field note. After collecting research data, the data were analyzed to come up with codes, themes, concepts, categories and relationships. The research data were analyzed using the thematic data analysis technique. Data derived through interviews were transcribed and uploaded to the Atlas Ti software and were grouped into relevant themes.

The transcribed interview scripts were read many times to understand their contents and possible themes within them. The invivo coding technique was adopted given that the research was based on the inductive research approach. The headings were used as the variables to describe and explain the factors that influence the diffusion of mPOS by small enterprise in the study context. This was followed by a more elaborate literature review during which we related the concepts, categories and relationships identified from the research data with existing formal theories and theoretical insights. Next the research model as developed and its implications on theory and practice were explained. Ethical considerations of the study include institutional permission granted by our university before the study was carried out. The institutional permission was granted after we had made application for ethical clearance, which involves stating the studies objectives, how the study is to be carried out and the group(s) that were involved in the study. We also sought the permission of small enterprise owners. We did an introductory letter where the requirements of the study were outlined. We explained to each participant that they reserve the right to withdraw from the study anytime the deem fit.

4. Presentation of Findings

4.1 Terms and Conditions and mPOS Adoption

The study’s objective is to find out the factors that influence the diffusion of mPOS in socio-economically unstable developing contexts. We used the Jimeta Metropolis, Yola, Adamawa State, Northeast Nigeria as a case of a socio-economically unstable developing context. Our findings show that there are a couple of terms and conditions that constituted challenges to the diffusion of mPOS in the study context. Terms and conditions denote requirements put in place by banks and financial institutions for regulating the diffusion of mPOS. Small enterprises must meet the terms and conditions if they are interested in adopting mPOS. It was gathered through interviews with the study participants that one of the terms and conditions required the payment of deposits. The deposits are amounts of money that must be deposited into the bank account small enterprises will use to run the mPOS. Participant 12 revealed that “You have to pay a deposit into the account connected to the POS”. He reveals that the deposits range between fifty thousand and hundred and fifty thousand naira. The deposit is the minimum account balance small enterprises are to maintain in the account they use to run the mPOS. Participant 8 indicated that “You can’t take a dime from the deposit…even if you are broke and need it badly.” The implication is that small enterprises were unable to withdraw the money as long as they used mPOS connected to the bank accounts. It was gathered that the deposits also served as caution fees and ‘insurance fees.’ The study participants revealed that the caution fees are security fees needed when small enterprises incur liabilities that may affect banks or other financial service providers that collaborate to provide mPOS services. However, banks and other financial service providers are to return the caution fees to small enterprises if they do not incur financial liabilities by the time they decide to stop using mPOS.

The study also revealed some other stringent conditions connected to the amount of money small enterprises must use mPOS to transact mPOS monthly. The condition stipulates that small enterprises must use mPOS to transact payments that range between thirty thousand naira per week and four hundred thousand naira per month. Participant 2 argued “How am I supposed to make that kind of amount with the kind of business I’m into. In this business we may not sell in two months, and once we sell it could run into millions.” Participant 12 argued that “…with what we sell and here in Yola, it could be very difficult to make the huge amount we are obliged to make using POS…it’s challenging and troubling and could take your mind from your business to issues regarding making the money banks require.” Our observation shows that this condition has a more diverse effect on the diffusion of mPOS by small enterprises than the condition that has to do with maintaining a minimum balance of fifty thousand naira. We observed through participatory observation that a couple of small enterprises had mPOS machines but were not using them. Many small enterprises stopped using mPOS due to the transaction requirement. We observed that most small enterprises that stopped using mPOS and those that did not consider mPOS a sustainable financial transaction technology did so, given the condition that required them to use mPOS to complete fixed-value of transactions. Although this factor constituted a diffusion factor, it did not affect all the small enterprises that were studied. The reason is that some small enterprises deal in businesses with high turnover. For instance, Participant 18 noted that “I don’t think about it. I run a business with high turnover. A lot of people buy things here every day and pay using POS.” Participant 12 on the other hand argued that “Meeting the set number of transactions is frustrating. I can’t even remember what the number is. I can’t reach the number with this kind of business.” We observed that the main factor determining how terms and conditions influenced the diffusion of mPOS in the study context is the turnover rate. The small enterprises that used mPOS at the time of the study were those, who due to the nature of their businesses, meet up with the required number of transactions per month.

Another term and condition small enterprises are to adhere to is namely, charging of commissions on every transaction performed using mPOS. The commission is charged against customers’ accounts by banks for any transaction completed with mPOS. The proceeds that are generated from the commissions paid by customers for using mPOS are shared by small enterprises and the financial service providers. Small enterprises have to take decision on if it is rewarding to bear the cost of the commission or for the customers to bear it. The implication is that small enterprises that adopt mPOS may have to take time to explain to customers the reason why commissions are charged against their bank accounts. According to the participants, the scenario resulted in the decline in the number of customers that were willing to transact payment using mPOS. Some small enterprises also lost some of their customers to small enterprises that took the decision to bear the cost of the commission on behalf the customers. This is considered disadvantageous because small enterprises that have not adopted mPOS do not have to go through the challenges those that have adopted mPOS go through due to commission charged against customers’ bank accounts. Participant 15 revealed that, “we have had situations in which we pay commission of about fifty naira or more and the customer whose ATM card was used was charged the same amount of money per transaction. How do you reconcile the charges? It’s not good business.” Study participants noted that charging customers extra on goods and services usually generate conflicts that results into loss of customers and in effect, loss of revenue. The term consequently, work against the diffusion of mPOS.

A practice that one would have deemed positive for small enterprises is the sharing of the commission paid by customers. It was revealed that banks and other financial service providers share the commission paid by customers with small enterprises periodically. The banks and other financial service providers however, get a higher percentage of the of the commission. Some of the study participants expressed displeasure that financial service providers get higher percentage of the commission. For instance, Participant 8, who owns a cosmetics store, complained about the sharing formula: “…the commissions should be looked into. Some platforms collect as much as 60 percent, leaving you with just 40. While you do the bulk of the work for them, that’s not a fair policy (sic). A 50-50 policy is even more understandable”. Participant 8 was frustrated with the reality that allows the service providers (banks and other financial service providers) to get more from the commission than small enterprise owners. The disparity in the commissions sharing formula was observed to have created a sense of unfairness between small enterprise owners and banks. The feeling that the sharing formula is unfair hampered the diffusion of mPOS by small enterprises given that some did not adopt mPOS after considering the commission sharing formula. It was revealed through observation, that small enterprises were interested in the commission because it will enable them to meet up with the obligation of help customers reduce the effects of the charges on their bank accounts. In summary, based on our observation and information derived from the interviews, it is obvious that the terms and conditions set for the acquiring mPOS negatively impacted on its diffusion by small enterprises in study context.

3.2 Types of Small Enterprise, Size of Small Enterprise, Customers’ Payment Preference and mPOS Adoption

The study also revealed three other adjoining factors that influenced the diffusion of mPOS in the study context. They are namely, types of small enterprise, the value of the small enterprises, that is, the value of their investments, and customers’ preferences for making payments. In the context of the study, the types of small businesses were determined by the types of products and services small enterprises deal with. For instance, there were small enterprises that produce and sell everyday life products such as food and beverages, detergents drinks, etc., and those that produce and sell textile materials, construction materials, etc. We categorized those that produce and sell everyday life products as different from those that produce and sell textile and construction materials and so on and so forth. On the other hand, categorization based on value of small enterprises was based on the amount invested by, and ‘size’ of each of the small enterprises studied. We have stated earlier that small enterprises net worth is usually between five million naira and fifty million naira. Consequently, among the small enterprises that we studied, some had about five-million-naira overall investment while some had between twenty-five million to fifty million naira. There are also some of whose investments were between ten and twenty million naira. There is also another factor namely, customer’s preferences for making payments. Customers’ preference for making payments denotes how customers want to make payments for the goods and services they purchase. This implies that customers’ willingness to pay for goods and services using mPOS or cash or any other type of payment impacted on small enterprises diffusion of mPOS.

Given the three adjoining factors, it follows that types of small enterprises, investment value and size of small enterprises and customers’ payment preferences impacted on small enterprises’ ability to meet up with the terms and conditions that were stipulated by banks and other financial service providers for adopting mPOS. For instance, owners of small businesses that were interviewed who deal in everyday products reported that their businesses were able to meet the terms and conditions stipulated by banks and other financial service providers. This is given that the types of small businesses they run promote high turnover rates and in effect, frequent diffusion of mPOS to transact payments. Consequently, these categories of small enterprises did not have any complaint about the terms and conditions that required them to complete stipulated number of weekly and monthly transactions and amount of money required to adopt mPOS. On the other hand, small enterprises that deal in products and services that do not enjoy high turnover found it difficult to meet the terms and conditions. The information we got through interviews corroborates the claims made by study participants on how terms and conditions, types of small enterprises, investment value (size) of small enterprises, and customers’ payment preferences influenced the diffusion of mPOS. Participant 7 for instance, who owns an electrical equipment retail outlet, stated that “My bank offered me a [mPOS] terminal once, but the conditions were too much. The cost and the number of transactions needed to maintain it was something that I can’t meet up with.” Participant 1 also indicated that, “…the banks have stringent conditions like a minimum amount of monthly transactions that must be made to keep their terminal.”

Participant 1’s position on stringent terms and conditions was corroborated by Participant 10: “They [commercial banks] require a minimum number of transactions, I have forgotten the exact number, with the nature of this our business I don’t think we can meet up with the frequency of transactions required. We don’t get customers coming in frequently like those in the supermarkets, so why should the bank require such from us?” It follows that based on the Participant’s claim that the types of small enterprise in question go a long way to determine if they are going to meet the number of transactions that they must complete per month that is stipulated in the terms and conditions for acquiring mPOS. Small enterprises that operate supermarkets and retail business sell everyday life products and services and consequently make a lot of sales per day. The high number of sales enables them to meet the terms and conditions connected to meeting stipulated daily and monthly transactions and in effect, the amount of financial transactions they must complete using mPOS. Small enterprises that deal in goods and services such as building materials and other goods and services that enjoy occasional patronage do not meet the daily and monthly transaction terms and conditions. It follows that the number of customers that patronize small enterprises differs by the products and services they offer and consequently, the likelihood that they will meet required transaction terms and conditions.

Participant 6 also expressed concerns about the terms and conditions relating to transaction frequency. Information provided by Participant 6 through interviews shows that the problem he was considering was not just the transaction frequency terms and conditions, but also customers’ preferences about how they will like to make payments. According to Participant 6: “Our account officer in the bank has been on my neck every time we speak on the phone or meet in person. He has been offering me the terminal, telling me what we could benefit from using it. I am not entirely oblivious of the benefits, but the conditions I feel are a bit not friendly, and considering the fact that most of our consistent customers prefer cash payments, I don’t think we could meet up with the stipulated frequency in transactions”. Information provided by Participant 6 shows how critical customers’ payment preferences are to mPOS diffusion by small enterprises. It follows that the amount of money a customer is required to pay may have also impacted on their preferences to pay for goods and services bought from small enterprises with cash. The more the amount of money required to be paid the likely a customer was willing to use mPOS. Considering this, we gathered that most of the customers that patronize small enterprises that sell everyday life products and services whose prices are between one hundred naira and two thousand naira usually pay in cash. These are amounts of money that can be carried around as cash in customers’ wallets. Consequently, small enterprises that deal in everyday life products and services claimed that most of their customers pay with cash. It follows that this category of small enterprises was able to meet up with transaction related terms and conditions given the high number of customers that patronize them daily. While they have numerous customers paying using cash, the also have a good number of customers who pay using mPOS. With regards to this, Participant 2 revealed during an interview that, “…while we have a good number of our customers pay using mPOS, a lot of them also pay with cash. Those who buy goods worth less than one or two thousand usually pay with cash. It is easy to pay that kind of amount using cash. We have a law, you can’t pay with POS if what you bought is less than five hundred naira”

3.3 Cognitive Structures, Sustainable Development and mPOS Diffusion

Two issues are underlying the information we got through the interviews and participatory observation done during the study. The issues are namely, the cognitive structures held by owners of the small enterprises about mPOS and the connection between mPOS and human development. It follows that a good number of small enterprise owners held negative cognitive structures about mPOS adoption. This is given that the terms and conditions required to adopt mPOS placed burdens that outweighed the benefits they could derive from mPOS adoption. Information provided by Participant 12 is a good indication that small enterprise owners developed negative cognitive structures about mPOS: “Meeting the set number of transaction is frustrating. I can’t even remember what the number is. I can’t reach the number with this kind of business.” During the participatory observation, we gathered that small enterprise owners would have adopted mPOS given that they wanted a payment transaction system that would help them reach set business objectives and goal. They wanted to make payments and manage their proceeds more efficiently using bank accounts. They also want to make profits, expand their customer base, employ more personnel, grow their businesses and enjoy a good and prosperous life. Small enterprise owners saw mPOS as a technology that have the potential to make them achieve set business objectives and goal. An extract from the interview held with Participant 18: “I really don’t think about it. I run a business with high turnover. A lot of people buy things here everyday and pay using POS” confirms this assumption.

However, the stringent terms and conditions which were reinforced by types of small enterprise, size of small enterprises, and customers’ payment preference negatively impacted the diffusion of mPOS among small enterprises and in effect, made their owners to develop negative cognitive structures about mPOS. The negative cognitive structures made small enterprise owners to have negative presumption about the benefits they could drive from adopting mPOS. This led to situations where those that have adopted mPOS stopped its use and those that are yet refused to adopt it. Another very cogent issue is the connection between achieving business objectives and goal and mPOS diffusion by small enterprises. Several business objectives were set by small enterprise owners. They include, efficient and effective payment systems, management of business proceeds, profit making, customer base expansion, employment of more personnel, businesses expansion and enjoying prosperous and good life. Participant 1 revealed that, “technology is good for business. I like to try them that is why I felt that POS will help me make my business to flourish.” Business objectives set by small enterprises are directly connected to sustainable development goals that could benefit small enterprise owners, the personnel they employ and their customers. Unfortunately, conditions surrounding the diffusion of mPOS make it difficult for small enterprise owners to use mPOS to improve on their contributions to sustainable development in the study context.

5. Theoretical Elaboration

In the extant literature, only a few scholars articulated the impact of terms and conditions on IT diffusion [68-71]. Another issue with the extant literature with regards to terms and conditions is that the terms and conditions identified by scholars are mostly those that are connected to transactional cost. This is the cost business owners and customers bear for using mPOS. For instance, Mallat [70] revealed that high commission and processing fee rates are key determinants of the diffusion of mPOS by small enterprises. Transaction cost and commission fee were also assessed in a study done by Mallat & Tuunainen [71] to expose consumers’ perception of mPOS. Onyebuchi [69] reveals that transactional costs are imposed by banks and financial service providers as a way of ensuring returns on investment in the infrastructure that support the operation of mobile payment systems. He also noted that transaction charges imposed by small enterprises on customers are necessitated by the need to cover up for financial gaps occasioned by transactional, processing or commission fees charged by banks and other financial service providers. Revelations in the extant literature indicate that transactional costs, processing fees and commissions can get very high and outweigh the benefits of mobile financial systems diffusion [69,71-73]. However, issues relating to minimum deposit as a term and/or condition for adopting mPOS have not been addressed in the extant literature. Our study however, shows that one of the terms and conditions set by banks and financial service providers that increases the cost of mPOS diffusion is the minimum deposit.

Another type of term and condition for adopting mPOS by small enterprises is the number of transactions to be completed every month. Our findings show that the ability of small enterprises to meet this term is dependent on their types and sizes. Small enterprises that deal in products and services that are needed on a daily basis, e.g. food, beverages and groceries did not find this particular term disturbing. However, small enterprises that deal in products and services that are required on a longer time range, e.g. textiles and clothing and construction products find the term disturbing. There has not been any study that provided a clear cut explanation of how types and sizes of small enterprises may determine if they will be able to meet some terms and conditions. Igudia [74] revealed that financial service providers require constant activity on the mPOS in order for it to be retained by enterprises that use it. However, he did not specify the conditions that made it difficult for the enterprises to meet the term. A study by Mallac [71] also superficially points to periodic requirements as a determinant for mobile payment adoption. Mallac’s study did not provide a clear explanation of what constitutes the periodic requirements. Anic et al. [75] on the other hand provided information that is close to the findings of this study by implying that requirements for constant use of mPOS might not be met by every type of business. Newer studies also point to customer types and turnover as critical factors to mobile payment diffusion [32]. The indication is that types and sizes of small enterprises constitute critical factors that determine the likelihood that small enterprises will meet mPOS diffusion requirements. It follows that there are no studies that directly infer to how types of small enterprises influence diffusion of mPOS. Our study explains how types of small enterprises, types of products and services, turnover rate and frequency of customers’ patronage impact the diffusion of mPOS.

There is another explanation that scholars have not provided namely, the impact of weekly or monthly transaction counts on the diffusion of mPOS. While this paper did not fully explain the scenario, it provides important insights into how requirements pertaining to weekly or monthly transaction counts promoted uneven business context that hampered mPOS adoption. We have noted earlier that we take mPOS as a special kind of IT that amplifies inputs, conversion factors, and choice and agency given Haenssgen & Ariana [53] postulation. Our study reveals that while mPOS has the potential to amplify these three variables, the social systems [37] also known as social arrangements [76], worked against it. In other words, the social arrangements put in place by banks and other financial service providers made it difficult for small enterprises to adopt mPOS. Our findings are consistent with Sen’s [48,52] postulation on how social arrangements could stand against sustainable development efforts. Consequently, despite that mPOS has the potential to amply business inputs, other conversion factors, capability sets and choice and agency, existing realities concerning these variables hampered its ability to amply them. This led to situations in which many small enterprises who have adopted mPOS jettisoned it. It also resulted in a situation where due to the negative reports of those that have adopted mPOS, many small enterprises that would have adopted it refused to adopt it. The scenario is consistent with insights in the diffusion of innovation literature on discontinuance decision which results to active rejection and passive rejection [37,77,78].

There is an important lesson to learn from the insights. First, the diffusion mPOS takes place within specific social systems or setups [34,37]. And because social systems are characterized by communication and interactions among social actors [34,79], active rejection is likely to lead to passive rejection. Consequently, mPOS diffusion is a socially constructed phenomenon. If this claim is anything to go by, mPOS diffusion should be driven by deliberately orchestrated concerted programs that are designed to put into cognizance the needs of all stakeholders. The implication of this will be a deliberate social construction of the social systems where mPOS diffusion is expected to take place. This will promote norms and values that enhance small enterprises’ capability sets and also enable them to freely make choices that are helpful to using mPOS to attaint desired functionings [37,48]. The construction of the social system should be done to give considerations to needs of customers, who patronize small enterprises. Customers have profound influence on the decisions made by businesses including, small enterprises [80]. A business owner may not adopt or incorporate a system if their customers will not use them [81]. Numerous studies have therefore underscored the importance of customers’ demand to the decision to adopt a mPOS [10,71,82]. The findings of this study on the non diffusion of mPOS by small enterprises given customers’ payment preference and the amount of money they are willing to spend during shopping is consistent with insights in the extant literature. This makes customers a critical stakeholder group in mPOS diffusion by small enterprises. The revelation makes the following question relevant. To what extent are small enterprises’ customers incorporated into, and participate in the social system where mPOS diffusion plays out? Are there communication channels available to small enterprises’ customers to communicate issues affecting mPOS diffusion with other stakeholders? And how do key stakeholders know about, and understand customers’ needs with regards to mPOS diffusion by small enterprises? The three questions raised are purely centered on the role of social arrangements in the extent IT can be promoted and in effect, enhance sustainable development [48,52].

There is also the issue of agency [83,84]. The findings of our study indicate that current social arrangements within the framework used to implement the diffusion of mPOS make small enterprise owners passive social actors. This is the reason why they did not have any say in the terms and conditions set to regulate the diffusion of mPOS. One challenge with the social arrangement is that it runs with the notion that all small enterprises are the same. The study’s findings negate this notion given that small enterprises were found to be distinguished by the products and services they deal in and their sizes. Small enterprise sizes are usually measured based on the value of their investments. These later factors are seen as adjoining factors that reinforces the negative impacts of terms and conditions on mPOS adoption. Whether banks and other financial service providers know about how the differences in characteristics of small enterprises negatively impact on mPOS diffusion is a question for another day. There is a deluge of studies that have advocated for participatory development and proposed the rationale for ensuring that participation is appropriately defined and implemented in development programs [85-88]. The philosophy underlying Sen’s concept of agency is that social actors should be treated as active participants in discussions and activities that directly affect their development [46,48]. Goodwin & Goodwin [89] opine that participation has to do with “…actions demonstrating forms of involvement performed by parties within evolving structures of talk [and activity]…[and not just] membership in social groups or ritual activities (p. 222).” It is very clear based on the findings of this study that small enterprises were not accorded the necessary level of participation. Issues related to how small enterprises characteristics affects mPOS diffusion were not given consideration by banks and financial service providers. This also denotes inaction by regulatory financial agencies and development agencies that promote the role of small enterprises in human development. The implication is that conversion factors and choices and agency remained in the negative mode and could not promote the desired social system where mPOS diffusion can thrive and used to spur human development. The findings of the study are represented in the research model below.

Figure 2: Factors Impacting mPOS Diffusion and Its Contribution to Sustainable development(Authors’)

6. Conclusion and Limitations

Our aim in the study was to derive and describe new mPOS diffusion factors as a way of diverting from ongoing tradition where factors inherent in IT adoption/acceptance theories such as TAM, extended TAM and UTAUT dominate ongoing debate. We adopted the inductive research approach given that it allows researchers to generalize based on data collected independent of existing theories. We backed our use of the inductive research approach with the subtle realism ontology. The subtle realism advocates that reality is independent of human mind and that reality can be accessed if distorted scientific methods are not used. Hence, our resolve not to use existing IT adoption/acceptance theories for the study. Consequently, the findings derived from the research data bring to the fore new variables including, terms and conditions of mPOS adoption, types and sizes of small enterprises, and customers’ payment preferences and indicate that we reached the aim of the study. The findings also provide new theoretical implication that shows that diffusion of innovation theory and capability approach theory are relevant to studying mPOS diffusion and its impacts on human development. Consequently, the study provides a novel knowledge that is critical to bridging the gap in knowledge with regards to the factors that come to bear in the diffusion of mPOS and other types of mobile payment systems and their connection with human development. We derive the following premises, mPOS is a special kind of input; mPOS would have amplified conversion factors if the social arrangements in the study context conceptualized small enterprise owners the active social actor status; if small enterprise owners were conceptualized as active social actors, they would have jointly created the conversion factors in ways that would have made it possible for mPOS to amply them. We therefore make the following generalization: mPOS could be used by small enterprise owners to reach their functionings, and in effect, sustainable developmentif the social arrangements in socio economically unstable developing contexts are enabling. The study shows the importance of social systems and arrangement in the diffusion of mPOS among small enterprises. There are a few limitations of the study which however, do not question its validity. The study is mainly descriptive and did not provide an elaborate explanation of the ‘whys’ the factors identified constrained mPOS diffusion and in effect, human development. Longitudinal explanatory study would be required to provide elaborate explanations on the ‘whys’ the factors identified in the study impact mPOS adoption, and in effect, human development. Additionally, the study only investigated mPOS diffusion in a metropolis in northeastern Nigeria adjudged as socio economically unstable context and came up with a generalization based on insights derived from the metropolis. Generalizing from single to broad is one of the main criticisms against the inductive research approach. A study of two or three or more metropolis would have provided avenue for comparison and more robust explanation.

Conflict of Interests:

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

Famiola, M., & Wulansari, A. (2019). SMEs’ social and environmental initiatives in Indonesia: An institutional and resource-based analysis. Social Responsibility Journal, 16(1), 15–27.View

Olagunju, F. & Utulu, S. (2021). Money Market Digitization Consequences on Financial Inclusion of Businesses at the Base of the Pyramid in Nigeria. In Ewa Lechman & Adam Marszk (Eds.), The Digital Disruption of Financial Services: International Perspectives, New York: Routledge View

Adanlawo, E., Vezi-Magigaba, M., & Owolabi, O. (2021). Small and Medium-scale Enterprises in Nigeria: The Effect on the Economy and People’s Welfare. African Journal of Development Studies (Formerly AFFRIKA Journal of Politics, Economics and Society), 11(2), 163–181.

Elijah, S., & Usaini, M. (2021). An empirical investigation of the role of small businesses in economic growth and poverty alleviation in north-western Nigeria. 25(2), 15. View

Shettima, M. B. (2021). Sustainability of micro, small and medium enterprise policies in Nigeria. International Journal of Business and Globalisation, 27(4), 478–491. View

Utulu, S. (2021). Framework for Coherent Formulation and Implementation of ICT Policies for Sustainable Development at the Bottom of the Pyramid Economy in Nigeria. In Walter Leal Filho, Rudi Pretorius & Luiza de Sousa (Eds.), Sustainable Development in Africa: Fostering Sustainability in one the World’s Most Promising Continent, (pp.633-648), New York: Springer. View

Choi, H., Park, J., Kim, J., & Jung, Y. (2020). Consumer preferences of attributes of mobile payment services in South Korea. Telematics and Informatics, 51, 101397. View

Alaeddin, O., Altounjy, R., Abdullah, N., Zaindin, Z., & Kantakji, M. (2019). The future of corruption in the era of cashless society. Humanities & Social Sciences Reviews, 7(2), 454-458.View

Ayoola, T. (2013). The effect of cashless policy of government on corruption in Nigeria. International Review of Management and Business Research, 2(3). View

Oyelami, L. O., Adebiyi, S. O., & Adekunle, B. S. (2020). Electronic payment diffusion and consumers’ spending growth: Empirical evidence from Nigeria. Future Business Journal, 6(1), 14. View

Aithal, P. S., (2015). How an Effective Leadership and Governance Supports to Achieve Institutional Vision, Mission and Objectives. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Development, Volume: 2, Issue: 5, pp. 154-161, e-ISSN: 2349-4182, p-ISSN: 2349-5979 View

Adeoti, O., & Osotimehin, K. (2012). Diffusion of Point of Sale Terminals in Nigeria: Assessment of Consumers’ Level of Satisfaction. Research Journal of Finance and Accounting, 3(1), 6

Park, J., Ahn, J., Thavisay, T., & Ren, T. (2019). Examining the role of anxiety and social influence in multi-benefits of mobile payment service. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 47, 140-149. View

Nwaolisa, E., & Kasie, E. (2012). Electronic retail payment systems: User acceptability and payment problems in Nigeria. Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review (OMAN Chapter) 1(9).View

Masihuddin, M., Khan, B.U.I., Olanrewaju, R.F., et al.,(2017). A Survey on E-Payment Systems: Elements, Adoption, Architecture, Challenges and Security Concepts. Indian Journal of Science and Technology, 10(20),1-19. View

Akerejola, W., Okpara, E., Ohikhena, P., & Emenike, P. (2019). Availability of infrastructure and diffusion of point of sales of selected small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in Lagos State, Nigeria. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 9(1), 137-150. View

Olasojumi, A., Ugwuchi, O., & Partrick, O. (2018). Awareness creation and diffusion of point of sales of selected small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in Lagos State, Nigeria. American Journal of Applied Scientific Research, 4(3), 33-40. View

Qasim, H., & Abu-Shanab, E. (2016). Drivers of mobile payment acceptance: The impact of network externalities. Information Systems Frontiers, 18(5), 1021–1034. View

Charmaz, K., & Belgrave, L. (2012). Qualitative interviewing and grounded theory analysis. The Sage Handbook of Interview Research: The Complexity of the Craft, 2, 347-365. View

Hayes, B., Heit, E., & Swendsen, H. (2010). Inductive reasoning. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews: Cognitive science, 1(2), 278-292.View

Montanari, S., & Kocollari, U. (2020). Defining the SME: A Multi-Perspective Investigation. In A. Thrassou, D. Vrontis, Y. Weber, S. M. R. Shams, & E. Tsoukatos (Eds.), The Changing Role of SMEs in Global Business: Volume II: Contextual Evolution Across Markets, Disciplines and Sectors (pp. 61–82). Springer International Publishing. View

Salder J, Gilman M, Raby S, et al. (2020). Beyond linearity and resource-based perspectives of SME growth. Journal of Small Business Strategy 30(1): 1–17. View

Davis, F. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 319-340.View

Venkatesh, V., & Davis, F. (2000). A Theoretical Extension of the Technology Acceptance Model: Four Longitudinal Field Studies. Management Science, 46(2), 186–204. View

Venkatesh, V. Morris, M. Davis, G. & Davis, F. (2003). User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425.View

DeLone, W., & McLean, E. (1992). "Information systems success: the quest for the dependent variable". Information Systems Research. 3 (1): 60–95. View

Daştan, İ., & Gürler, C. (2016). Factors affecting the diffusion of mobile payment systems: An empirical analysis. EMAJ: Emerging Markets Journal, 6(1), 17-24. View

Mou, J., Shin, D., & Cohen, J. (2017). Trust and risk in consumer acceptance of e-services. Electronic Commerce Research, 17(2), 255-288. View

Zhou, T. (2014). An empirical examination of initial trust in mobile payment. Wireless Personal Communications, 77(2), 1519-1531.View

Sinha, M., Majra, H., Hutchins, J., & Saxena, R. (2019). Mobile payments in India: the privacy factor. International Journal of Bank Marketing.View

Hoofnagle, C., Urban, J., & Li, S. (2012). Mobile payments: Consumer benefits & new privacy concerns. Available at SSRN 2045580.View

de Luna, P., Hahn, C., Higgins, D., Jaffer , S. A., et al. (2019). What would it take for renewably powered electrosynthesis to displace petrochemical processes? Science. 26- 364(6438):eaav3506.View

Chandra, S., Srivastava, S., & Theng, Y. (2010). Evaluating the role of trust in consumer diffusion of mobile payment systems: An empirical analysis. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 27(1), 29.View

Sahin, I. (2006). Detailed review of Roger’s diffusion of innovation theory and educational technology-related theory based on Roger’s theory. The Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 5(2), Article 3.View

Utulu, S. & Sote, T. (2009) African Information Society Initiative, Technology Transfer and the Evolution of Digital Information and Knowledge Management Systems in Africa. A paper presented at the International Conference on Managing Information in the Digital Era, University of Botswana, Gaborone, Botswana, October, 14-16. View

Kinnunen, J. (1996). "Gabriel Tarde as a Founding Father of Innovation Diffusion Research". Acta Sociologica. 39 (4): 431– 442.View

Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations. New York: Free Press.View

Avgerou, C. (2017). Theoretical Framing of ICT4D Research. In J. Choudrie, M. S. Islam, F. Wahid, J. M. Bass, & J. E. Priyatma (Eds.), Information and Communication Technologies for Development (Vol. 504, pp. 10–23). Springer International. View

Mumford, E. (2006). The story of socio-technical design: Reflections on its successes, failures and potential. Information systems journal, 16(4), 317-342. View

Nandonde, F. (2018). Stand-alone retail owners’ preference on using mobile payment at the point of sales (POS): Evidence from a developing country. In Marketing and Mobile Financial Services (pp. 159-177). Routledge. View

Dasuki, S., & Effah, J. (2021). Mobile phone use for social inclusion: the case of internally displaced people in Nigeria. Information Technology for Development, DOI: 10.1080/02681102.2021.1976714.View

Bailey, A., & Ngwenyama, O. (2013). Toward entrepreneurial behavior in underserved communities: An ethnographic decision tree model of telecenter usage. Information Technology for Development, 19(3), 230-248. View

Sahay, S., & Walsham, G. (1995) Information technology in developing countries: A need for theory building, Information Technology for Development, 6(3-4), 111-124. View

Anand, S., & Sen, A. (2000). Sustainable developmentand economic sustainability. World development, 28(12), 2029- 2049.View

Ranis, G., Stewart, F., & Ramirez, A. (2000). Economic growth and human development. World development, 28(2), 197-219. View

Sen, A. (1992). Inequality reexamined. Oxford: Oxford University Press. View

Sen, A. (1976). Poverty: an ordinary approach to measurement. Econometrica, 44(2),219-231. View

Sen, A. (2013). The ends and means of sustainability. Journal of Sustainable developmentand Capabilities, 14(1), 6-20. View

Oosterlaken, I., & Van den Hoven, J. (2011). ICT and the capability approach. Ethics and Information Technology, 13(2), 65-67.View

Walker, M., & Unterhalter, E. (2007). The capability approach: Its potential for work in education. In Amartya Sen’s capability approach and social justice in education (pp. 1-18). Palgrave Macmillan, New York. View

Nussbaum, M. (1993). Social justice and universalism: In defense of an Aristotelian account of human functioning. Modern Philology, 90, S46-S73.View

Sen, A. (2010). The mobile and the world. Information Technologies and International Development, 6(Special issue), 1–3.View

Haenssgen, M., & Ariana, P. (2018). The place of technology in the Capability Approach, Oxford Development Studies, (46)1, 98-112.View

Robeyns, Ingrid. (2005). The Capability Approach: A Theoretical Survey. Journal of Sustainable developmentand Capabilities. 6. 93-117. 10.1080/146498805200034266.View

Klauer, K., & Phye, G. (2008). Inductive reasoning: A training approach. Review of Educational Research, 78(1), 85-123.View

Blaikie, N. (2018). Confounding issues related to determining sample size in qualitative research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 21(5), 635-641.View

Hammersley, M. (2002). Ethnography and realism. In: The qualitative researcher’s companion, Michael Huberman & Matthew B. Miles (Eds.), pp.: 65-80, Sage.View

Paseau, A. (2021). Arithmetic, enumerative induction and size bias. Synthese, 199(3), 9161-9184.View

Harman, G. (1968). Enumerative induction as inference to the best explanation. The Journal of Philosophy, 65(18), 529-533.View

Ramalho, R., Adams, P., & Hoare, K. (2015). Literature review and constructivist grounded theory methodology. In Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 16(3), 1-13.View

Walls, P., Parahoo, K., & Fleming, P. (2010). The role and place of knowledge and literature in grounded theory. Nurse Researcher, 17(4).View

Gioia, D., Corley, K., & Hamilton, A. (2013). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organizational Research Methods, 16(1), 15-31.View

Walls, J.L., Berrone, P. and Phan, P.H. (2012), Corporate governance and environmental performance: is there really a link?. Strat. Mgmt. J., 33: 885-913.View

Sharma, G. (2017). Pros and cons of different sampling techniques. International Journal of Applied Research, 3(7), 749-752.View

Etikan, I., Musa, S., & Alkassim, R. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American journal of theoretical and applied statistics, 5(1), 1-4. View

Low, J. (2007). Unstructured interviews and health research. In: Researching Health: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods, Mike Saks & Judith Allsop (Eds.), pp. 74-89, London: Sage.

Klenke, K. (2008). Qualitative research in the study of leadership (1st ed.). Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Pub. View

Igudia, O. (2018). Electronic Payment Systems Diffusion by SMEs in Nigeria: A Literature Review. Nigerian Journal of Management Sciences Vol, 6(2).View

Onyebuchi, B. (2016). Mobile Banking – Diffusion and Challenges in Nigeria. 11. View

Mallat, N. (2007). Exploring consumer diffusion of mobile payments – A qualitative study. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 16(4), 413–432. View

Mallat & Tuunainen. (2008). Exploring Merchant Diffusion of Mobile Payment Systems: An Empirical Study. E-Service Journal, 6(2), 24. View

Liébana-Cabanillas, F., Molinillo, S., & Ruiz-Montañez, M. (2019). To use or not to use, that is the question: Analysis of the determining factors for using NFC mobile payment systems in public transportation. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 139, 266-276. View

Iman, N. (2018). Is mobile payment still relevant in the fintech era?. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications. 30. 10.1016/j.elerap.2018.05.009. View

Igudia, O. (2016). An Integrated Model of the Factors Influencing the Diffusion and Extent of Use of E-Payment Systems by SMEs in Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Management Sciences 26.View

Anic, I.-D., Radas, S., & Lim, L. K. S. (2010). Relative effects of store traffic and customer traffic flow on shopper spending. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 20(2), 237–250. View

Sen A. (1999). Development as Freedom. New York: Alfred Knopf.View

Dube, C., & Gumbo, V. (2017). Diffusion of innovation and the technology diffusion curve: Where are we? The Zimbabwean experience. Business and Management Studies, 3(3), 34-52. View

Peshin, R., Vasanthakumar, J., & Kalra, R. (2009). Diffusion of innovation theory and integrated pest management. In Integrated pest management: Dissemination and impact (pp. 1-29). Springer, Dordrecht. View

Utulu, S., & Ngwenyama, O. (2021). Multilevel analysis of factors affecting open-access institutional repository implementation in Nigerian universities. Online Information Review, 45(7). View

Plouffe, C. R., Bolander, W., Cote, J. A., & Hochstein, B. (2016). Does the Customer Matter Most? Exploring Strategic Frontline Employees’ Influence of Customers, the Internal Business Team, and External Business Partners. Journal of Marketing, 80(1), 106–123. View

Grønholdt, L., Martensen, A., Jørgensen, S., & Jensen, P. (2015). Customer experience management and business performance. International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences, 7(1), 90–106.View

Abrahão, R. de S., Moriguchi, S., & Andrade, D. (2016). Intention of diffusion of mobile payment: An analysis in the light of the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT). RAI Revista de Administração e Inovação, 13(3), 221–230.View

Miletzki, J., & Broten, N. (2017). An Analysis of Amartya Sen's: Development as Freedom. Macat Library. View

Sen, A. (1981). Poverty and famines: an essay on entitlement and deprivation. Oxford: Clarendon Press View

Mwanzia, J.S., & Strathdee, R.C. (2010). Participatory Development in Kenya (1st ed.). Routledge. View

Kyamusugulwa, P. M. (2013). Participatory Development and Reconstruction: a literature review. Third World Quarterly, 34(7), 1265-1278. View

Singh, J. (2008). Paulo Freire: Possibilities for dialogic communication in a market-driven information age. Information, Communication & Society, 11(5), 699-726. View

Cornwall, A. (2003). Whose voices? Whose choices? Reflections on gender and participatory development. World development, 31(8), 1325-1342.View

Goodwin, C., & Goodwin, M. (2004). Participation. In A companion to linguistic anthropology, A. Duranti (Ed.), (pp. 222-243), Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Limited. View