Journal of Political Science and Public Opinion Vol. 2 iss. 2 (Jul-Dec) 2024, Article ID: JPSPO-110

https://doi.org/10.33790/jpspo1100110Research Article

Do Punitive Politicians Have a Better Chance of Getting Elected? A Secondary Analysis of Survy of Politicians and Voters in Japan

Tomoya Mukai

Department of Psychology, Faculty of Human Culture and Sciences, Fukuyama University, 985-1, Sanzo, Higashimura-machi, Fukuyama-city, Hiroshima, 729-0292, Japan.

Corresponding Author Details: Tomoya Mukai, Senior Lecturer, Department of Psychology, Faculty of Human Culture and Sciences, Fukuyama University, Japan.

Received date: 30th April, 2024

Accepted date: 04th July, 2024

Published date: 06th July, 2024

Citation:Mukai, T., (2024). Do Punitive Politicians Have a Better Chance of Getting Elected? A Secondary Analysis of Survy of Politicians and Voters in Japan. J Poli Sci Publi Opin, 2(2): 110.

Copyright: ©2024, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Abstract

The theoretical framework of penal populism posits that the trend towards punitive penal policies is driven by a process whereby voters tend to elect punitive politicians and once elected, these politicians push for policies that are in line with their personal attitudes. However, the existence of such a mechanism has not yet been confirmed by empirical evidence. This study aims to clarify this mechanism by conducting a secondary analysis of Politician and Voter Surveys collected in Japan during the 2009 House of Representative elections: proportional representation and single-member constituency elections. The study seeks to answer the following three research questions: (1) Are politicians who support punitive policies more likely to be elected? (2) Do voters who support punitive policies tend to vote for political parties that also support punitive policies? and (3) Who tends to be more supportive of punitive policies, politicians or voters? The analysis of the study showed that: (1) politicians who were more supportive of punitive policies had a greater chance of being elected, (2) voters who supported punitive policies tended to vote for political parties that also supported them, and (3) voters were generally more supportive of punitive policies.

Key words: Penal Populism, Death Penalty, Punitiveness, Election, Japan

Introduction

Penal populism has been a key theoretical framework that is used to understand the recent developments in penal policies [1,2]. Put simply, penal populism refers to ‘policies that favor a “tough” stance on crime and crime control issues’ [3]. Originally coined by Bottoms [4] as ‘popular punitiveness’, this framework has primarily been applied to Western societies such as New Zealand and Australia [5], Scandinavian countries [6,7], and the UK and Norway [8]. However, later scholars have also rigorously applied this framework to Asian countries such as Japan [3,9,10], South Korea [11,12], China [13], and the Philippines [14], although some of them have questioned the straightforward applicability of the framework [11,13].

Despite the widespread influence of the penal populism framework and the efforts of researchers to apply it to specific contexts, there are relatively few empirical (quantitative) studies that have tested the assumptions of this framework. Moreover, as discussed below, one of the basic assumptions of penal populism is that public punitiveness influences the decisions of politicians. However, while some scholars argue that mass incarceration in the United States is the result of increased public punitiveness [15], there is currently no direct evidence to support this assumption, and the relationship between politicians’ attitudes towards penal policies and their electoral success has not been empirically examined. The current study aims to provide empirical evidence for the penal populism framework by investigating whether politicians’ attitudes towards penal policies have an impact on their likelihood of being elected.

In the following sections, the theoretical framework of penal populism and its assumptions will be briefly explained and the data source used in this study to test these assumptions will be presented. Then, it will present three research questions (RQs) that are the focus of this study, and the results of a series of three analyses conducted to answer the questions.

Penal Populism as a Theoretical Framework

Although the emphasis varies among scholars, penal populism generally explains recent developments in penal policy as follows: In modern societies, criminal justice system was primarily controlled by experts and insulated from public influence [16]. However, due to various social changes, such as declining trust in authority and politicians, globalization and increased fear of crime [17], the hegemony of experts in the system is weakening in contemporary societies. This ‘dramatic reconfiguration of the axis of penal power’ [5] has resulted in more punitive penal policies being adopted based on the preferences of the public, who tend to be more punitive than experts [18] and who have a more prominent role in shaping penal policy.

While the penal populism framework is useful for understanding recent developments in penal policy in many societies, one of its caveats is that its emphasis is not consistent among its proponents. Existing studies of political populism can be divided into two main strands: those that focus on political elites, typically politicians, who are on the ‘supply side’ of populism, and those that examine the public, who are on the ‘demand side’ in the sense that they have a choice about whether to accept the populist ideas offered by these political elites. For example, studies that primarily examine the attitudes and behaviors of specific politicians [19,20] can be classified as 'supply-side' studies, while those that develop scales to measure public support or approval of populist ideologies [21,22] are considered ‘demand side’ studies.

This difference in emphasis can also be seen in studies of penal populism, although they often overlap and are difficult to distinguish. As an example of a ‘supply side’ study, Roberts et al. [18] define populism as ‘a political response that favors popularity over other policy considerations’ (p. 3) and, based on this definition, argue that penal populism is characterized by ‘the pursuit of a set of penal policies to win votes rather than to reduce crime rates or to promote justice’ (p. 5). As this definition and characterization focuses primarily on policy and politicians, the work of Roberts et al. [18] can be seen as a ‘supply-side’ study.

Pratt [5] ’s work, on the other hand, can be seen as a study that focuses mainly on the ‘demand side’ of penal populism. Although it does not provide a simple definition, it focuses on the social transformations that are thought to underpin penal developments. These transformations include various social factors, such as declining trust in ‘establishments’, including academics, the judiciary and some sections of the media, and the transformation of the media and society at large. As Pratt’s [5] arguments are not limited to the political arena and focus mainly on changes in society at large, this study can be considered a ‘demand side’ study.

Despite the variations in emphasis, examining the effects of politicians’ attitudes on the likelihood of being elected can provide valuable insights in the sense that it fills a research gap that exists in both strands of research. In the ‘supply side’ research, penal populism is characterized as ‘the pursuit of a set of penal policies to win votes’ [18] and this is seen as a driving force behind more punitive policies. Thus, this line of research seems to assume a mechanism whereby the public votes for politicians who hold (or present themselves as holding) punitive attitudes. Empirical testing of this assumed mechanism is therefore highly relevant to this line of research. On the other hand, the study of politicians’ attitudes is less relevant to ‘demand-side’ research because it is primarily concerned with broader social configurations that are not limited to politics or elections [5], and testing the validity of the above mechanism does not affect the validity of ‘demand side’ studies. However, Pratt himself, who focuses mainly on the ‘demand side’, repeatedly refers to elections in a study of penal policy in New Zealand [23], suggesting that elections have at least some relevance to this line of research. Thus, the study of politicians’ attitudes is relevant within the theoretical framework of penal populism.

However, it has not been a focus of empirical studies. Many studies have been conducted to explore public attitudes towards penal policy and their determinants in both Western [24-27] and Asian contexts [28-32], and some of them [33-35] even refer to the late modernity perspective [36], which shares basic assumptions or world views that societies have been destabilized and people living in such societies have become more anxious [1,37]. In addition, Enns [15] has argued, based on an analysis of time series data on incarceration and public opinion, that mass incarceration in the US was caused by an increase in public punitiveness. However, as far as is known, no studies have directly examined the attitudes of politicians. Given the centrality of this issue to punitive populism, this research gap needs to be filled with empirical evidence.

Data Source

The lack of research on this topic is understandable, especially given that as access to politicians can be a challenge for researchers. In Japan, however, there is a publicly available dataset named the ‘UTokyo-Asahi Survey’ [38] that can be used for this purpose. This dataset, a collaboration between researchers at the University of Tokyo and Asahi Press, one of Japan’s largest press companies, includes data collected for 14 elections between 2003 and 2022, and the data for each election include responses from political candidates (politicians) and voters. Many items are identical between the Politician and Voter Surveys, but a few are different.

In addition, although the majority of questions in the surveys are not directly related to penal policy, there are some questions that gauge the respondents’ (i.e. politicians’ and voters’) attitudes towards penal policy. These include questions measuring support for punitive policy and the death penalty (for further details, see Analytical Strategy), as well as a question relating to the support for restrictions on private rights or the perceived importance of public safety (‘It is natural for privacy and private rights to be restricted in order to protect public safety’).

However, while the third item (support for restriction of private rights) is included in most waves of the survey, including the most recent 2022 survey, the other two items (support for punitive policies and the death penalty), which are more relevant to the current study, are only included in the 2009 survey. Therefore, in order to examine these items, the analysis was limited to the data collected in 2009.

Given the time gap between 2009 and now, and the fact that the survey was conducted in Japan, a country that is sometimes considered to have an ‘exceptional’ criminal justice system and crime rate [39], the research using this dataset is unlikely to be applicable to the current system and may not be of interest to researchers who do not have a specific focus on the Japanese context. Nevertheless, research in the Japanese context may offer unique perspectives that may not be available in other contexts. In particular, Japanese society is often characterized by relatively low rates of reported crime and incarceration [40]. While there was a temporary increase in both rates in the late 1990s and early 2000s, they have been steadily decreasing since 2003 [41]. In addition, there were other pressing issues in 2009, such as the reform and privatization of the postal service, the change of government from the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) which is often regarded as conservative and therefore punitive, to the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ), and the reform of the pension system. Therefore, overshadowed by other pressing issues, crime was not a major electoral issue in 2009, and it is likely that penal policy was not a central consideration for most voters during the decision-making process in 2009. In this context, research on trust and cooperation has shown that the effect of value similarity on trust and cooperation is stronger when the issue is more salient to the respondent [42,43]. Given this evidence, it can be expected that the relationship between voters’ and politicians’ values at this time and society is less close, and thus the effects of politicians’ attitudes on their likelihood of being elected are weaker than in other times and society where penal policy is a more salient issue. Considering these, an investigation in the Japanese context can serve as a ‘hard case,’ meaning that the assumption of the penal populism framework is less likely to hold valid than in other societies, for investigating the relationship between voters’ and politicians’ attitudes. Thus, if this relationship is found in the current study, it is likely to be applicable to other contexts and societies.

Current Study

The current study aimed to contribute to the existing literature by testing a mechanism that: 1) the public tends to be more punitive than politicians; 2) among them, those with more punitive attitudes tend to vote for more punitive parties; and accordingly, 3) politicians with more punitive attitudes have a greater chance of being elected. In order to test this assumed mechanism, the corresponding three research questions (RQs) were examined.

RQ1: Did support for punitive policy, support for the death penalty and restriction of private rights increase a candidate’s likelihood of being elected?

RQ2: Did voters who support the death penalty and restriction of private rights vote for a political party with the same tendencies as themselves?

RQ3: Who was more supportive of the death penalty and restriction of private rights, politicians or voters?

The reason for examining RQ1 was that this is the basic mechanism assumed in the theoretical framework of penal populism (especially in ‘supply side’ studies) [18], and clarifying this mechanism would provide some insights into the framework. However, answering RQ1 does not reveal how voters’ attitudes affect their voting behavior. Therefore, RQ2 was also investigated. In contrast to RQ1, RQ2 does not include support for punitive policies, as this item is not included in the Voter Survey. In addition, this RQ focused on voting behavior for parties rather than for politicians themselves. This was due to data availability. There are two types of election for the House of Representatives in Japan: the proportional representation and the single-member constituency elections. In the former, voters vote for political parties rather than politicians, so there is no data on which politicians they voted for; and in the latter, the original dataset did not include data on which politicians respondents voted for. RQ3 was examined using the combined data from politicians and voters. The theoretical framework of penal populism argues that the influence of the ‘establishment’, including politicians and others, is weakened and instead the influence of citizens is strengthened, leading to a more punitive criminal justice system [5]. Such arguments assume (though do not necessarily explicitly argue) that citizens are more punitive than ‘experts’ such as politicians. In this regard, Roberts et al. [18], who examined the attitudes of citizens, showed that most citizens are generally punitive, but they did not present data directly comparing politicians and citizens using the same items. Therefore, RQ3 was examined to complement this point.

Analytical Strategy

In order to answer the above RQs, three analyses were conducted using the data from the 2009 Politician and Voter Surveys. Analysis 1 examined RQ1 regarding the probability of politicians being elected, using data from the Politician Survey. First, to get an overview of the data, the means of each item measuring politicians’ punitive attitudes were calculated and their correlations and the difference between political party affiliations were examined. Then, to answer RQ1, a logistic regression analysis was conducted with the election result as the independent variable and politicians’ punitive attitudes as the dependent variable. Analysis 2, which addressed RQ2, examined whether voters’ punitive attitudes influenced their voting behavior mainly using data from Voter Survey. Specifically, voters’ scores on the items regarding support for the death penalty and restriction of private rights were regressed on the corresponding scores for each political party obtained in Analysis 1. In Analysis 3, addressing RQ3, data from the Politician and Voter Surveys were combined and their differences were tested using t-tests. All analyses were conducted using R ver. 4.2.1.

Analysis 1

Methods

Participants

The 2009 Politician Survey included responses from 1,303 candidates. However, this included responses with missing values. Excluding the incomplete responses, data from 1,261 candidates were used in the analysis. The questionnaire was sent to all candidates on 13 July 2009 and returned upon completion. The response rate was 94.8%.

Variables

(1) Election result: The Japanese electoral system uses parallel voting, a mixed electoral system combining proportional representation and single-member constituency elections. Accordingly, politicians who were elected under either electoral system are coded as 1 and those who were not are coded as 0.

(2) Support for punitive policy: For this item, respondents were first presented with two opposing views: ‘A: Social safety is deteriorating and we should promote harsher punishment for crime / B: Social safety is not deteriorating and we should be cautious about harsher punishment for crime’. They were then asked to rate which view they were closer to. Responses were coded as Close to A (5), Somewhat closer to A (4), Neither close to A nor B (3), Somewhat closer to B (2) and Close to B (1), with higher scores indicating greater support for the punitive policy.

(3) Support for the death penalty: Respondents were asked whether they agreed or disagreed with the statement: ‘The death penalty should be abolished.’ Respondents were coded as disagree (5), somewhat disagree (4), neither agree nor disagree (3), somewhat agree (2) and agree (1), with higher scores indicating greater support for the death penalty.

(4) Support for restriction of private rights:Respondents were asked whether they agreed or disagreed with the statement ‘It is natural for privacy and private rights to be restricted in order to protect public safety’. Responses were coded as agree (5), somewhat agree (4), neither agree nor disagree (3), somewhat disagree (2) and disagree (1), with higher scores indicating greater emphasis on security and support for restrictions on private rights.

In addition to these independent and dependent variables, the following variables were treated as controls. In terms of party affiliation, there were a total of 12 parties at the time of the 2009 elections. However, three of these parties— ‘Japan Renaissance Party (Kaikaku Kurabu)’ (n = 1), ‘New Power DAICHI (Shinto Daichi)’ (n = 2) and ‘New Party Nippon (Shinto Nippon)’ (n = 6)—had fewer than 10 respondents. Including parties with such a small number of respondents could make an estimate unreliable. Therefore, along with the options other parties and no party affiliation, respondents belonging to these three parties were coded as others. Other variables controlled for were number of times elected, experience of being elected, gender and age. Regarding gender, men were coded as 1 and women as 2. Regarding experience, three options were dummy coded: none, elected in the last election and elected in the older election(s). The other two variables (number of times elected and age) were treated as continuous.

Results

Preliminary Analysis

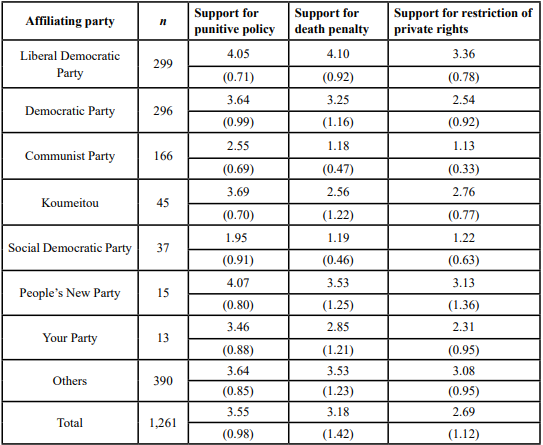

In order to get an overview of the data, the mean for each independent variable was calculated according to the parties to which the politicians were affiliated (Table 1). The correlations between the dependent variables were then examined. The correlation between support for the death penalty and punitive policy was r = .54, that between support for the death penalty and restriction of private rights was r = .54, and that between support for punitive policy and restriction of private rights was r = .48. All were highly significant (p < .01).

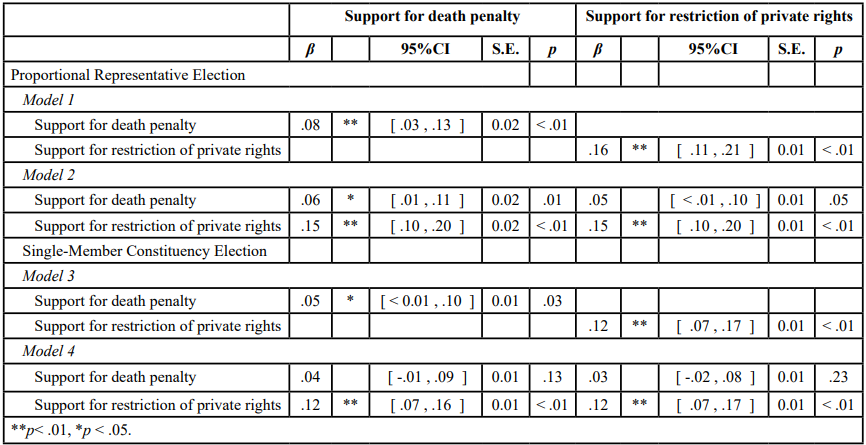

Logistic Regression Analysis

To address RQ1, a logistic regression analysis was conducted with the election result as the dependent variable. As the dependent variables were found to be highly correlated, their separate effects were estimated in Models 1 to 3. Model 4 included all variables including controls. As shown in Table 2, the estimation revealed that support for the death penalty and penal policy had significant effects on the election result, suggesting that a one standard deviation increase in support for the death penalty and punitive policy increases a politician’s likelihood of being elected by 21% (11%-32%) and 28% (14%-45%), respectively. In contrast, support for the restriction of private rights did not show such an effect. In addition, in Model 4, which controls for all variables, support for the death penalty and penal policy did not show significant effects.

Analysis 2

Methods

Participants

The 2009 Voter Survey included responses from 2,086 voters (aged older than 20). However, this included responses with missing values. Excluding the incomplete responses, data from 1,579 voters were used in the analysis. Respondents were selected using a two stage stratified random sampling technique. The questionnaire was sent to respondents on 29 August 2009, one day before the elections, and collected by 31 October. The response rate was 69.5%.

Variables

Parties for which respondents voted in the proportional representation and single-member constituency elections were used as dependent variables. Respondents who voted for parties not listed in the options were coded as others. Also, those who chose the option ‘blank vote, invalid vote, etc. (abstained at the polling station)’ were excluded from the analysis as missing values.

The items measuring support for the death penalty and the restriction of private rights were coded in the same way as in Analysis 1. Support for punitive policy was not examined because the voter survey did not include this item.

Results

Preliminary Analysis

As in Analysis 1, the mean for each independent variable was calculated by voting party (Table 3). The correlation between support for the death penalty and restriction of private rights was r = .13 (p < .01).

Table 3: Sample sizes and means (standard deviations) by voters' voting parties and type of elections

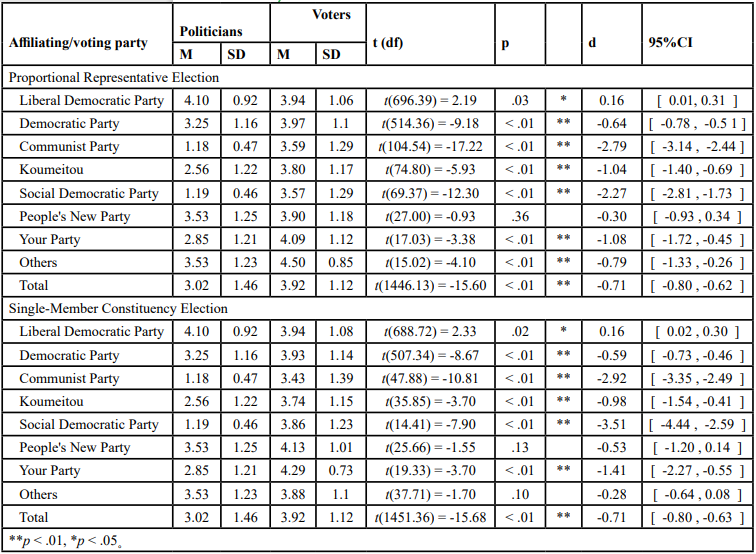

Regression Analysis

First, the respondent’s party vote was matched to the mean party support for the death penalty and restriction of private rights scores obtained in Analysis 1, and these scores were treated as dependent variables in the regression models. For example, if a voter voted for the LDP, since the mean score for the death penalty was 4.10, this score was matched and treated as the dependent variable. In Models 1 and 3, only variables corresponding to the independent variable in each model (either support for the death penalty or restriction of private rights) were included in the models. In Models 2 and 4 another dependent variable (either restriction of private rights or support for the death penalty) was added to control for its possible effects.

As shown in Table 4, the estimation results show that in Models 1 and 3, which include only one dependent variable, the effects of each dependent variable are consistently significant (βs > .05, ps < .03). Furthermore, these effects remained significant when controlling for another dependent variable (βs > .06, ps < .01), with the exception of Model 4 (β = .04, p = .13).

Analysis 3

Methods

Participants

The Politician and Voter Surveys used in Analyses 1 and 2 were analyzed again. Excluding responses with missing values, data from 1,261 politicians and 1,579 voters were used in the subsequent analysis.

Variables

The items measuring the support for the death penalty and restriction of private rights were used. They were coded in the same way as in Analyses 1 and 2.

Results

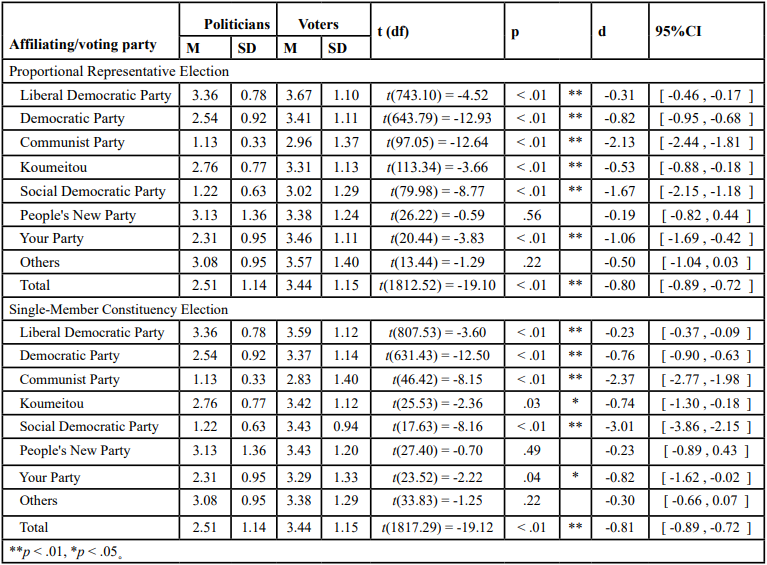

Welch’s t-tests were used to examine the differences between politicians’ and voters’ support for the death penalty and the restriction of private rights. As the data for voters included two variables on voting party (those who voted in proportional representation election and those who voted in single-member constituency election), these were matched with politicians’ party affiliation and tested separately.

As for support for the death penalty (Table 5), voters’ scores were significantly higher for all parties except the LDP and the People’s New Party (PNP). The differences for the latter were not significant in either the proportional representation election (t(27.00) = -0.93, p = .36, Hedges’ d = -0.30) or the single-member constituency election (t(25.66) = -1.55, p = .13, d= -0.53), probably due to the small sample size (15 for politicians and 29 for voters). The result for the LDP in the PRE was unique in that it was the only party in which politicians scored significantly higher than voters (t(696.40) = 2.19, p = .03, d = 0.16).

Regarding the support for the restriction of private rights (Table 6), voters’ scores were higher than politicians’ scores in all parties except the PNP. The difference with the PNP did not reach a significant level in either election (PRE: t(26.22) = -0.59, p = .56, d = -0.19; SMDE: t(27.40) = -0.70, p = .49, d = -0.23).

Table 6: Difference between politicians' and voters' support for restriction of private rights by parties

Overall Discussion

Drawing on the arguments of penal populism as a theoretical framework, the present study aimed to examine how punitive attitudes of politicians affect their likelihood of being elected and how they are related to the attitudes of the public. As a result of a series of three analyses using data from Politician and Voter Surveys, three findings were obtained. First, an analysis of the politician data showed that politicians who supported the death penalty and punitive policy were more likely to be elected. Specifically, a one standard deviation increase in support for the death penalty and punitive policy increased the probability of being elected by about 21% and 28%, respectively. Second, an analysis of voter data shows that respondents who support the death penalty are more likely to vote for a party that supports the death penalty. Third, a comparison of politicians and voters shows that, with few exceptions, voters are more supportive of the death penalty and restriction on private rights than politicians. Taken together, these findings suggest that voters, who are generally more punitive than politicians, tend to vote for parties with attitudes similar to their own, thereby facilitating the election of more punitive politicians.

The current study contributes to both strands of the penal populism literature, as distinguished in the introduction. The findings of the present study contribute to the ‘supply side’ line of research [18], which focuses mainly on electoral and political behavior and attitudes, in the sense that the findings provide some of the first empirical (quantitative) evidence for their arguments that punitive politicians are more likely to be elected. In addition, the present findings also contribute, albeit not directly, to the second line of research—the ‘demand side’ study—which focuses not only on the political arena but also on wider social situations [5], as the findings show that the election of a politician can be a way through which public attitudes are introduced into the political arena, thereby influencing penal policies and social situations at large. To sum, the present study contributes to the both strands of existing literature by suggesting the possibility of a political mechanism by which voters’ punitive attitudes are translated into the political arena by increasing the likelihood that punitive politicians will be elected.

Limitations

However, this suggestion should be balanced and tempered by the three considerations. First, it should be noted that the present study does not claim to have provided direct empirical support for this framework or to have lent support to either side of the ongoing debate between those who argue that Japan is in a penal populist situation and those who question it [10,44]. To provide such support, further theoretical work on the definition of penal populism itself and empirical studies are warranted. Secondly, as a major caveat of the present study, it is worth noting that the relationship between politicians’ and voters’ attitudes could be influenced by the third variable. That is, in Analysis 1, the effects of support for penal policy and the death penalty were not significant after controlling for party affiliation in Model 4. Since individual politicians are expected to choose to belong to a particular party because of similarities in their attitudes, it is quite natural for the effect of party to override the effect of attitudes, and therefore this does not seem to seriously reduce the validity of the proposition. However, it is still possible that politicians’ decisions to affiliate with a particular party are influenced by other factors and that their attitudes towards penal policy do not play a major role. In order to isolate the effects of attitudes towards penal policy from other factors, more controlled studies or qualitative studies of small cases may be needed.

Another limitation worth discussing is the generalizability of the present findings. As discussed in the Introduction, the crime issue was not a salient election issue at the time of the 2009 elections, and under such circumstances, voters were unlikely to emphasize value similarity on the crime issue [42,43]. Therefore, the targeted study case — the 2009 elections in Japan — can be regarded as a hard case in which the relationships between politicians’ and voters’ attitudes are less likely to be observed than in other situations and times. However, the results of the series of three analyses have consistently shown that politicians’ and voters’ attitudes are closely related. Given this, it may be the case that the present findings can be applied to other situations and times when the crime is a more salient issue. However, as this prediction is speculative, it should be read as a suggestion that raises an important research question for future studies, rather than a conclusion.

The third limitation is mainly due to the secondary nature of the present analysis. Specifically, while the present study examined the relationship between politicians' attitudes and their chances of being elected, it is questionable whether voters had detailed knowledge about the politicians they voted for. In addition, the item used in the present study to measure punitive attitudes was slightly double barreled, meaning that it confounded punitive attitudes and fear of crime. Since punitive attitude and fear of crime are closely related [45], it may be acceptable to ask for both constructs in the same item. Nevertheless, it is more desirable in future studies to clearly distinguish these constructs. In addition, while the present study did not distinguish whether politicians won in PRE and SMCE in Analysis 1 and aggregated individual politicians' and voters' attitudes at the group (i.e., party) level in Analyses 2 and 3, it should be recognized that the meaning of winning in PRE and SMCE is different and that there are variations in attitudes even among politicians and voters who belong to and voted for the same party, so the present study may have failed to uncover potentially interesting findings by ignoring these variations. Finally, while support for punitive policies and the death penalty showed a significant relationship with election outcome, their effect was insignificant once variables such as party affiliation, experience, and number of elections were controlled for. This fact may challenge the present conclusion by implying that the relationship between punitive attitudes and electoral result may be influenced by other factors.

Future Research Orientations

In conclusion, this study contributes to the existing literature by empirically suggesting the existence of a mechanism consistent with the penal populism assumption, with some limitations that are mainly due to the secondary nature of the present study. Based on the present findings and limitations, some future research orientations can be envisaged.

The first direction for future research is to examine the determinants of both politicians’ and voters’ attitudes. Although studies have been conducted in Japan [34] and other Asian countries [32] on the determinants of the attitudes of voters (the general public), no studies have been conducted on politicians. Second, conducting a time series analysis may be a promising future direction. The data set includes not only the 2009 data analyzed in this study, but also data collected during other elections. In the future, it would be useful to use the same dataset to examine, in particular, the determinants of politicians’ attitudes and how they have changed over time.

Running Head:

Do punitive politicians have a better chance of getting elected?

Acknowledgements

Open data from the UTokyo-Asahi Survey [38] were used in this study.

Competing Interest:

The author declares that he has no competing interests.

References

Garland, D. (2001). The culture of control: Crime and social order in contemporary society. University of Chicago Press.View

Simon, J. (2007). Governing through crime: How the war on crime transformed American democracy and created a culture of fear. Oxford University Press.View

Fenwick, M. (2013). ‘Penal populism’ and penological change in contemporary Japan. Theoretical Criminology, 17(2), 215 231.View

Bottoms, A. (1995). The philosophy and politics of punishment and sentencing. In C. Clarkson & R. Morgan (Eds.), The politics of sentencing reform (pp. 17–50). Oxford University Press.View

Pratt, J. (2007a). Penal populism. Routledge.View

Pratt, J. (2007b). Scandinavian exceptionalism in an era of penal excess: Part I: The nature and roots of Scandinavian exceptionalism. British Journal of Criminology, 48(2), 119 137.View

Pratt, J. (2008a). Scandinavian exceptionalism in an era of penal excess: Part II: Does Scandinavian exceptionalism have a future? British Journal of Criminology, 48(3), 275–292.View

Green, D. A. (2008). When children kill children: Penal populism and political culture. Oxford University Press.View

Kyo, S. (2021). A quantitative analysis of legislation with harsher punishment in Japan. Asian Journal of Law and Society, 9(1), 81–107.View

Miyazawa, S. (2008). The politics of increasing punitiveness and the rising populism in Japanese criminal justice policy. Punishment and Society, 10(1), 47–77.View

Choo, J. (2009). Critical review of punitiveness universality: Trends and issues in literatures. Korean Criminological Review, 28(2),155-179. (In Korean with English abstract)View

Lee, H. Y. (2020). A punitive but non-punitive society: An explanation of the specificity of penal populism in South Korea. Victoria University of Wellington.View

Li, E. (2017). Penological developments in contemporary China: Populist punitiveness vs. penal professionalism. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, 51, 58–71.View

Kenny, P. D., & Holmes, R. (2020). A new penal populism? Rodrigo Duterte, public opinion, and the war on drugs in the Philippines. Journal of East Asian Studies, 20(2), 187–205. View

Enns, P. K. (2014). The public’s increasing punitiveness and its influence on mass incarceration in the United States. American Journal of Political Science, 58(4), 857–872.View

Garland, D. (1985). Punishment and welfare: A history of penal strategies. Quid Pro Books.View

Pratt, J. (2008b). Penal scandals in New Zealand. In A. Frieberg & K. Gelb (Eds.), Penal populism, sentencing councils and sentencing policy (pp. 31–44). Routledge.View

Roberts, J. V., Stalans, Loretta, J., Indermaur, D., & Hough, M. (2003). Penal populism and public opinion: Lessons from five countries. Oxford University Press.View

Judis, J. B. (2016). The populist explosion: How the great recession transformed American and European politics. Colombia Global Report.View

Taggart, P. (2000). Populism. Open University Press.View

Akkerman, A., Mudde, C., & Zaslove, A. (2014). How populist are the people? Measuring populist attitudes in voters. Comparative Political Studies, 47(9), 1324–1353.View

Wettstein, M., Schulz, A., Steenbergen, M., Schemer, C., Müller, P., Wirz, D. S., & Wirth, W. (2020). Measuring populism across nations: Testing for measurement invariance of an inventory of populist attitudes. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 32(2), 284–305.View

Pratt, J., & Clark, M. (2005). Penal populism in New Zealand. Punishment and Society, 7(3), 303–322.View

Hirtenlehner, H., Groß, E., & Meinert, J. (2016). Fremdenfeindlichkeit, Straflust und Furcht vor Kriminalität: Interdependenzen im Zeitalter spätmoderner Unsicherheit. Soziale Probleme, 27(1), 17–47.View

Silver, J. R., & Silver, E. (2017). Why are conservatives more punitive than liberals? A moral foundations approach. Law and Human Behavior, 41(3), 258–272.View

Tyler, T. R., & Boeckmann, R. J. (1997). Three strikes and you are out, but why? The psychology of public support for punishing rule breakers. Law and Society Review, 31(2), 237 265.View

Unnever, J. D., & Cullen, F. T. (2010). Racial-ethnic intolerance and support for capital punishment: A cross-national comparison. Criminology, 48(3), 831–864.View

Gideon, L., & Hsiao, Y. G. (2012). Stereotypical knowledge and age in relation to prediction of public support for rehabilitation: Data from Taiwan. Asian Journal of Criminology, 7(4), 309 326.View

Huang, H. fen, Braithwaite, V., Tsutomi, H., Hosoi, Y., & Braithwaite, J. (2012). Social capital, rehabilitation, tradition: Support for restorative justice in Japan and Australia. Asian Journal of Criminology, 7(4), 295–308.View

Jou, S., & Hebenton, B. (2020). Support for the death penalty in Taiwan? A study of value conflict and ambivalence. Asian Journal of Criminology, 15(2), 163–183.View

Lambert, E. G., & Jiang, S. (2006). A comparison of Chinese and US college students’ crime and crime control views. Asian Journal of Criminology, 1(1), 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11417-006-9006-8View

Wu, Y. (2014). The impact of media on public trust in legal authorities in China and Taiwan. Asian Journal of Criminology, 9(2), 85–101.View

King, A., & Maruna, S. (2009). Is a conservative just a liberal who has been mugged? Exploring the origins of punitive views. Punishment and Society, 11(2), 147–169.View

Mukai, T., Fukushima, Y., Iriyama, S., & Aizawa, I. (2021). Modeling determinants of individual punitiveness in a late modern perspective: Data from Japan. Asian Journal of Criminology, 16(4), 337–355.View

van Marle, F., & Maruna, S. (2010). “Ontological insecurity” and “terror management”: Linking two free-floating anxieties. Punishment and Society, 12(1), 7–26.View

Giddens, A. (1990). The consequences of modernity. Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University.View

Roberts, J., & Hough, M. (2005). Understanding public attitudes to criminal justice. Open University Press.View

Taniguchi, M. (2022). The UTokyo-Asahi survey. Retrieved January 22, 2023, from http://www.masaki.j.u-tokyo.ac.jp/utas/ utasindex.html (in Japanese)View

Brewster, D. (2020). Crime control in Japan: Exceptional, convergent or what else? British Journal of Criminology, 60(6), 1547–1566.View

Rennó Santos, M., Weiss, D. B., & Testa, A. (2022). International migration and cross-national homicide: considering the role of economic development. International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, 46(2), 119–139.View

Research and Training Institute, M. of J. (2021). White paper on crime 2021.View

Mukai, T., Nozawa, Y., Ohta, T., Miyagawa, R., & Nakagawa, K. (2020). Determinants of support for the “recycling demonstration project for the soil generated from decontamination activities” in postdisaster Fukushima, Japan. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 24(2), 252–260. View

Nakayachi, K., & Cvetkovich, G. (2010). Public trust in government concerning tobacco control in Japan. Risk Analysis, 30(1), 143–152.View

Hamai, K., & Ellis, T. (2008). Genbatsuka: Growing penal populism and the changing role of public prosecutors in Japan. Japanese Journal of Sociological Criminology, 33, 67–92. View

Singer, A. J., Chouhy, C., Lehmann, P. S., Stevens, J. N., & Gertz, M. (2020). Economic anxieties, fear of crime, and punitive attitudes in Latin America. Punishment and Society, 22(2), 181–206.View