Journal of Political Science and Public Opinion Vol. 3 iss. 1 (Jan-Jun) (2025), Article ID: JPSPO-118

https://doi.org/10.33790/jpspo1100118Research Article

Visual Analysis of National Security Economics Based on Bibliometrics

Kaixuan Wang1, Bo Chen2, and Yu Song3*

1School of Economics, Central University of Finance and Economics, Beijing, China.

2Institute of Defense Economics and Management, Central University of Finance and Economics, Beijing, China.

3Institutes of Science and Development, Chinese Academy of Sciences, No. 15,North One, Zhongguancun, Haidian District, Beijing, China.

Corresponding Author: Yu Song, Institutes of Science and Development, Chinese Academy of Sciences, No. 15, North One, Zhongguancun, Haidian District, Beijing, China.

Received date: 13th January, 2025

Accepted date: 13th March, 2025

Published date: 17th March, 2025

Citation: Wang, K., Chen, B., & Song, Y., (2025). Visual Analysis of National Security Economics Based on Bibliometrics. J Poli Sci Publi Opin, 3(1): 118.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Abstract

Using bibliometric methods based on the CiteSpace, and employing keyword co-occurrence analysis, keyword clustering analysis, and timeline analysis, this paper summarizes the hotspots of the national security economics in different periods, the differences between China and worldwide potential causal mechanism. The main findings of this paper are: (1) The themes primarily focus on national security, Sino-U.S. relations, major power competition, and economic growth; (2) Under the background of great power competition, the national security economics combine with international trade, industrial policy and technological competition have become research frontiers; (3) There are differences between China and the worldwide, with China’s research being characterized by stage-specific due to Sino U.S. strategic interactions, while research from worldwide focus on certain areas and dynamic in some issues; (4) There are hidden casual paths among them, suggesting possible casual mechanisms. This paper enriches discussions on the national security economics using bibliometric methods, and reveals some potential casual links, contributing to a better understanding of the field’s internal logic and policy-making.

Keywords: National Security Economics, Bibliometric, Research Hotspots, Research Differences, Potential Causal Mechanism.

Introduction

National security is the foundation and prerequisite for ensuring a country’s economic development and social stability. It is also an inherent requirement in forming a national strategic competitive advantage. At present, the geopolitical situation is complex and changing. At the meanwhile, the strategic competition among major powers is accelerating, and the uncertainty of the global economy is increasing. National security issues have not only become a severe challenge in reality but also a hot topic in the academic. Therefore, it is necessary to focus on the research status of national security economics.

As the international situation evolves, current research on the national security economics differs from the past. It now focuses on new issues and hotspots. Where are the current research hotspots concentrated? What distinctions exist between China and the worldwide in this field, and what characteristics define these divergences? Furthermore, what potential causal mechanisms interconnect research themes within the national security economy? To gain a comprehensive understanding of this field, it is essential to analyze research from both vertical and horizontal perspectives. This includes exploring the underlying causal mechanisms between different research themes, a gap in current bibliometric research. To address these needs, this study utilizes bibliometric methods based on CiteSpace. In view of this, based on the CNKI and WoS databases, this paper employs the bibliometric method by using of CiteSpace to statistically analyze and content mine the literature on national security economics. Furthermore, according to the knowledge map, analyzing the hotspots and frontier, clarifying the trend of national security economics research, which is conducive to providing a reference for further research by scholars.

Theoretical Foundations and Literature Review

The theories on national security economics primarily come from the fields of international relations, politics, and economics. Since Adam Smith, economic analysis of security has been around [1]. Neoclassical Economics sees defense as a pure public good, shown in arms races, alliances, and defense burden studies [2-3]. Among the theory on national security, Realism posits that the motivation for maintain national security stems from the pursuit of military and economic power [4]. It argues that conflicts among states are inevitable unless a dominant hegemonic power exists. Liberalism highlights interdependence and cooperation among states to reduce conflict risks and promote mutual gains [5]. Recently, the theory of weaponized interdependence notes that economic interdependence can have negative effects and be used as coercion tools [6,7]. Constructivism explains the expansion of national security’s scope from the military domain to political, economic, technological, and the environmental [8,9]. Economic statecraft emphasizes governments using economic policies to ensure national security and boost economic development. With accelerating technological revolutions and industrial transformations, countries are increasingly leveraging trade and industrial policies to drive technological innovation and industrial upgrading, thereby gaining strategic advantages in great-power competition. This is a key manifestation of contemporary economic statecraft [10,11].

There are already many achievements in the form of literature reviews themed on national security. Early studies primarily focused on the relationship between war and the economy, based on defining the scope of research in national security economics. Review studies by Lincoln [12], Hitch [13], and Dunne [14] clarified traditional topics such as defense budgets, war-related economic strength, and economic warfare, providing a clear analytical framework and laying the foundation for subsequent research. As times evolved, scholars began to examine national security economics from a broader perspective, no longer focusing solely on wartime economic phenomena but expanding the research scope to include military alliances and economic foreign policies closely related to national security [15,16]. Some scholars further reviewed prior research, systematically analyzing the bidirectional causal relationships between the economy and national security, providing important references for subsequent studies [17,18]. In recent years, review studies on national security economics have expanded from traditional security fields to non-traditional security areas, increasingly focusing on specific issues related to national security and the economy. These include financial security [19], energy security [20], climate change [21], supply chain flexibility [22,23], and cybersecurity [24].

Early research in national security economics have laid a solid groundwork for understanding these relevant topics. While the evolving global landscape and emerging interdisciplinary approaches present opportunities to better understand the field. Existing reviews, through their historical background, offer valuable insights into the field’s development. However, the limited use of bibliometric tools may constrain interdisciplinary connections. Additionally, as research themes diversify with contemporary challenges, further exploration of potential relationship between security and economic factors could strengthen theoretical coherence. Besides, combined quantitative literature review with qualitative causal inference may deepen understanding.

Methodology

Bibliometrics is a traditional method for analyzing literature quantitatively. It helps grasp research hotspots and trends in a certain field. Its applications have expanded to medicine [25], biochemistry [26], environmental resources [27,28], etc., with strong universality and applicability. Recently, using knowledge map tools for visual bibliometric analysis of research dynamics and trends in specific fields has become common. Some scholars have applied this to visual analysis of specific areas in non-traditional security economics, such as energy security [29,30], climate change [31], financial stability [32], as well as traditional security domains like defense spending [33]. However, these specific-field studies can’t show the overall research status and trends in national security economics. Therefore, combining bibliometric tools for an overall analysis of national security economics is necessary. Which will help scholars understand the evolution of research themes, current hotspots, and frontiers.

Currently, common bibliometric tools include CiteSpace and VOSviewer. CiteSpace can generate knowledge maps through keyword co-occurrence, clustering, and timeline, showing the evolution of research hotspots and possible causal mechanisms. In contrast, VOSviewer cannot track research evolution, calculate betweenness centrality, or identify key nodes and causal relationships. Therefore, this paper uses CiteSpace for visual bibliometric analysis. However, the CiteSpace has limitations. First, its results depend on the database. Web of Science is English-biased, missing Chinese literature. So, this paper uses both China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) and Web of Science (WoS) databases. Second, knowledge maps from CNKI in CiteSpace are in Chinese, leading to mixed-language figures, which is also a limitation of this paper. Despite this, CiteSpace remains a classic bibliometric tool.

This paper primarily employs bibliometric methods to analyze the current research of literature related to national security economics. Utilizing the CiteSpace and bibliometric analysis tool, which integrates social network analysis and cluster analysis, this study explores the hotspots, research trends, and intrinsic connections among hotspots at different periods. Consequently, based on the CiteSpace visualization tool, aiming to provide references for future studies, through keyword co-occurrence analysis and cluster analysis, and constructs a knowledge map of its research trends, this paper explores the research hotspots of national security economics.

Data Sources

The data sources of this paper mainly come from two databases. The Chinese literature is from the CNKI database, while the English literature is from the WoS database. When searching in the CNKI database, this paper sets the theme as “national security”, limiting the discipline to economics-related fields, and restricts the journal sources to those from Peking University’s core journals, CSSCI, AMI, CSCD, EI, and SCI. In addition, considering that national security is a research subject at the intersection of international relations and economics, we manually screen the retrieved data to retain only the economic research. This resulted in 293 valid data entries, spanning the years from 2015 to 2024. When searching the WoS database, this paper confined the search scope to the WoS Core Collection and limited the journal sources to SSCI. Furthermore, by using the keywords “national security” and “economic*” for thematic search, the relevant economic analyses were filtered out. After removing duplicate literature, 321 English literature records were obtained, covering the years from 2002 to 2024.

Co-occurrence Analysis of Keywords

Keywords are a concise summary of a paper, and the frequency of their occurrence can reflect their importance in the network. Therefore, analyzing the keywords of literature can grasp the research hotspots in this field to a certain extent. Based on this, this paper uses CiteSpace to draw the co-occurrence map and clustering map of keywords. Among them, the co-occurrence map of keywords can reflect the frequency of the appearance of keywords, represented by nodes. The larger the node, the higher the frequency, the lines between nodes represent the relationships between keywords. The clustering map of keywords can reflect the similarity between keyword nodes, and cluster nodes with similar keywords according to certain standards, thereby depicting the cutting-edge hotspots over a period of time. Furthermore, this paper also draws a ten-year timeline of national security economics research to analyze the hot topics and trends in different periods.

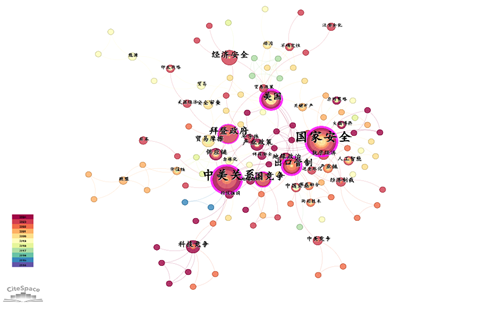

Co-occurrence Analysis of Keywords in the China’s Research

Figure 1 presents the co-occurrence map of keywords from the CNKI from 2015 to 2024, which includes 182 nodes and 262 connections. Each node represents a keyword, and the size of the node reflects its significance. As shown in Figure 1, the node for “national security” is the largest. Given that “national security” is a crucial keyword in the search criteria, its high frequency of occurrence is expected. The keywords Sino-U.S. relations and great power competition rank second and third in frequency, indicating that they represent key research directions in this field. Additionally, keywords such as Biden administration, United States, export control, economic security, industrial policy, technological competition, trade friction, geopolitics, and supply chain also have high frequencies, suggesting that they are at the forefront and hotspots of current research.

In terms of centrality, the centrality value of “national security” is the highest at 0.39, indicating that it occupies a central position in the network and serves as a link to other hotspots. The centrality values of “Sino-U.S. relations” and “United States” are also relatively high, ranking second and third at 0.33 and 0.30, respectively, suggesting that they play a strong role in connecting different aspects within the field of national security economics research. This also reflects that under the backdrop of Sino-U.S. strategic competition, the game between the two countries are not only key factors affecting national security but also important subjects of national security economics.

By comparing the frequency of keyword occurrences with their centrality, it can be observed that there are inconsistencies between the two. This is because these two indicators can characterize the distribution of current hotspots from different perspectives, thereby allowing for a further understanding of the hotspots in national security economics research. For example, the keyword great power competition has a low centrality of only 0.11, but a high frequency of occurrence, reflecting the attention and emphasis that scholars place on the study of great power competition. Additionally, the keyword export control has a relatively high centrality of 0.21, indicating that it plays a strong connecting role among different hotspots. However, its frequency of occurrence is only 8, which is relatively low. This suggests that the current level of attention from scholars towards this aspect still needs to be improved. There is a need to further strengthen the emphasis on export control research within the field of national security economics, in order to promote the perfection of the research content and system.

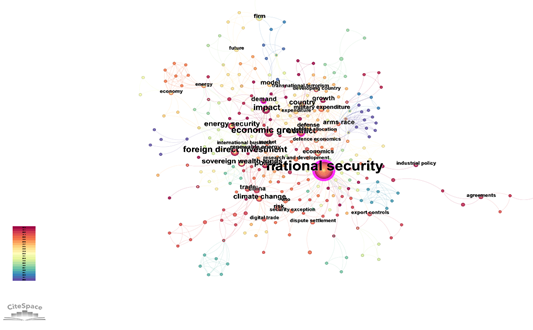

Co-occurrence Analysis of Keywords in the International Research

Figure 2 presents the co-occurrence of keywords in the WoS database from 2002 to 2024. As shown, the larger the circle node, the higher the frequency. The keyword national security has the largest node, occurring 70 times. Additionally, economic growth and foreign direct investment also have high frequencies, ranking second and third, respectively, and are mainly concentrated in studies in 2002 and 2007. In the past decade, keywords such as conflict, climate change, renewable energy, defence economics, export control, and industrial policy have received more attention from scholars. It is worth noting that although “renewable energy” has a high frequency in recent years and is a hot topic among scholars, its centrality is low, indicating a weaker connection with other themes in national security economics.

Cluster Analysis of Keywords

Cluster Analysis of Keywords in the China’s Research

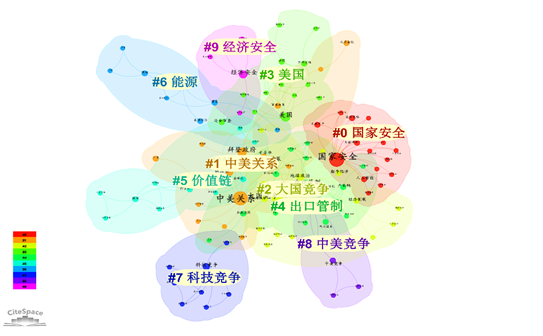

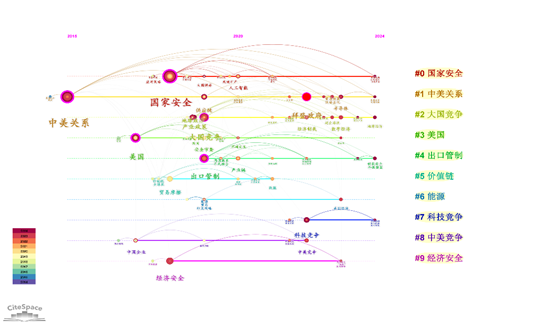

To further analyze the keyword combinations in national security economics, we conduct a clustering analysis of high-frequency keywords, resulting in a keyword clustering map as shown in Figure 3. Generally, a clustering map with a modularity value Q > 0.3 is considered to have significant community structure, and an average silhouette value S > 0.7 indicates that the clustering is highly efficient and convincing. In Figure 3, Q = 0.7357 and S = 0.909, which suggests that the clustering map has research value. Figure 3 shows the formation of 9 clusters, that is, #0 National Security, #1 Sino-U.S. Relations, #2 Great Power Competition, #3 United States, #4 Export Control, #5 Value Chain, #6 Energy, #7 Technological Competition, #8 Sino-US Competition, #9 Economic Security.

Further, we focus on the top 6 clusters with the largest scales. Specifically, cluster #0 National Security is the earliest cluster to reach the threshold, which includes keywords such as great power technological competition, Sino-U.S. strategic competition, and great power games. These indicate that, compared to traditional national security economic research, scholars have expanded their understanding of national security-related issues over the past decade. Most studies are based on the interactions between China and the United States, highlighting the strategic significance of economic variables, and exploring the relationship between development and security through the games among great powers. Cluster #1 Sino-U.S. Relations includes keywords such as trade policy, securitization, and technological containment strategy. Under the influence of uncertainties in the international environment, the perception of securitization threats has deepened and expanded in the practice of Sino-U.S. relations. The U.S. has intensified its technological competition with China by generalizing export controls and investment reviews, forming the main thread of Sino-U.S. strategic competition. Consequently, there is a wealth of literature on Sino-U.S. strategic competition in the field of technology from the perspective of national security. Cluster #2 Great Power Competition includes keywords such as geopolitics, industrial policy, and economic sanctions. Great power competition, a traditional topic in international relations and politics, has now essentially shifted to competition in industrial policy. As industrial policy becomes a tool for great power competition, competitive confrontation among great powers has intensified. Geopolitical risks have rapidly increased, drawing widespread attention from scholars, as well.

Cluster #3 the United States includes keywords such as the Trump administration, security reviews, and uncertainty. Current research primarily focuses on the interactions between China and the United States, especially the series of economic and strategic interactions since the Trump administration. Cluster #4 Export Control includes keywords such as industrial chains, dual-use technologies, and military-civilian integration. The rapid rise of Chinese technology has challenged the U.S. dominance in the global industrial chain and broadened its security implications, using export controls as a key policy tool to implement technological containment against China. Scholars’ research on export controls mainly focuses on the political intentions and economic impacts behind them. Cluster #5 Value Chains includes keywords such as trade friction, globalization, and the Sino-U.S. trade war, focusing on the analysis of the impact of trade friction on global value chains in the context of globalization.

Cluster Analysis of Keywords in the International Research

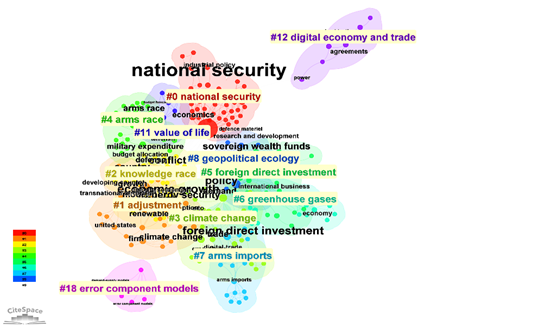

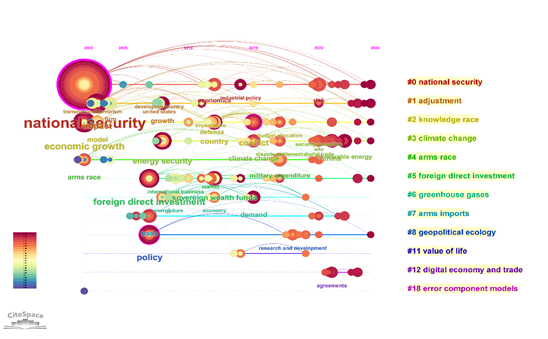

Figure 4 presents the keyword clustering of research on national security economics from the worldwide. As shown in Figure 4, 19 clusters were formed with Q = 0.7903 and S = 0.9301, indicating a reliable clustering result. The clusters are #0 National Security, #1 Adjustment, #2 Knowledge Race, #3 Climate Change, #4 Arms Race, #5 Foreign Direct Investment, #6 Greenhouse Gases, #7 Arms Imports, #8 Geopolitical Ecology, #11 Value of Life, #12 Digital Economy and Trade, #18 Error Components Models.

Among them, cluster #0 National Security includes keywords such as export controls and economic security, with the average year of research appearance being 2014. Cluster #1 Adjustment mainly involves keywords like economic adjustment, uncertainty, and developing country. Cluster #2 Knowledge Race primarily includes keywords such as Schumpeterian growth, hostile external threat, and foreign military threat, with the main year of appearance being 2015. Cluster #3 Climate Change includes main keywords like cluster analysis and energy efficiency, with research concentrated around 2019. Cluster #4 Arms Race includes main keywords such as defence burden, defence expenditure, defence economics, and arms trade, with the average year of research appearance around 2008. Cluster #5 Foreign Direct Investment related research mainly appeared in 2013, including keywords like emerging markets. Cluster #6 Greenhouse Gas mainly includes keywords such as federal subsidy policy and vehicle electrification. Cluster #7 Arms Import mainly includes keywords like military expenditures and international trade. Cluster #8 Geopolitical Ecology includes main keywords such as R&D expenditure and oil supply. Cluster #11 Value of Life includes keywords such as national security and terrorism, with the average year of research appearance being 2016. Cluster #12 Digital Economy and Trade includes main keywords such as globalization and data privacy, with the average year of research appearance being 2022. Cluster #18 Error Components Models appeared on average in 2002, including main keywords such as crowding-out, defence R&D spending, and investment.

Differential Analysis of National Security Economics

Through co-occurrence analysis, cluster analysis, and timeline analysis of keywords, it is evident that there are distinct emphases and significant differences in the research content on national security economics between the two databases. Overall, domestic Chinese literature primarily focuses on the strategic interactions between China and the United States, with hotspots related to the U.S. government’s national security strategy and international situation. In contrast, scholars from worldwide have a broader research scope, often starting from the concept of national security and the practical interactions among major economies, covering a wider range of aspects including military security, economic security, climate change, energy security, and human security.

Characteristics of China’s Research on National Security Economics

Based on the analysis of keyword frequencies and clustering presented above, we can identify that, in China’s national security economics research, the current hotspots are primarily focused on the following three areas.

First, the manifestations of Sino-U.S. strategic competition (clusters #2, #4, #7). In the era of globalization, the close interdependence among nations has not promoted economic cooperation but instead increased sensitivity and vulnerability, leading major powers to shift from cooperation to confrontation. As the United States has designated China as a primary strategic competitor, trade and economic frictions and competition between the two countries have intensified, which characterized by the weaponization of interdependent relationships and justified a series of actions to sever networked rights, such as decoupling in high-tech fields, investment security reviews, and financial economic sanctions, in an attempt to contain and suppress the rising power based on asymmetric dependencies to achieve so called security goals.

Second, the economic effects of Sino-U.S. strategic competition (clusters #5, #6, #9). The current international situation is complex and volatile, with great power competition increasingly focusing on key resources, product production, and important nodes in the global industrial and supply chains. The global value chain has restructured the global industrial structure, leading to deindustrialization in some developed economies, which have begun to exert pressure on emerging countries to control the global value chain. Third, factors influencing Sino-U.S. strategic competition (clusters #0, #1, #3). This primarily involves discussions and analyses of the motivations behind Sino-U.S. strategic games, such as the reasons for industrial policy competition between the two countries, the impact of technological gaps on strategic competition, and the influence of coercive power and the weaponization of interdependence on strategic competition.

Characteristics of International Research on National Security Economics

Similarly, based on frequency and clustering analysis, we can also summarize the current hotspots from worldwide, which are mainly focused on the following four areas.

First, the economic effects of traditional security (clusters #4, #7, #8). International research primarily focuses on the economic effects of traditional security factors, with an emphasis on defense economics. This includes the impact of defense on national innovation systems [34], the spillover effects of defense expenditure on economic growth [35,36], the impact of defense expenditure on employment [37], and the economic security effects of arms trade [38]. Additionally, research examines the economic impacts of traditional insecurity factors, such as the effects of interstate wars and conflicts on domestic and neighboring countries’ economic growth and development [39,40], the impact of terrorism on foreign direct investment [41,42], the impact of terrorism on international trade [43], and the effects of other insecurity factors on business operations and innovation [44], human capital [45,46], and social welfare and preferences [47,48].

Second, the impact of economic and quasi-economic factors on national security (cluster #5). This is mainly manifested in two aspects. The one is the study of the impact of foreign direct investment (FDI) on national security, and the other is about the international practices of the concept of national security, such as increased foreign investment security reviews and restrictions on investment entry, exploring the impact of these quasi-economic factors on national security and development. Rosecrance and Thompson [49] argue that FDI has a high opportunity cost, and FDI links between two countries are more likely to reduce the occurrence of conflicts than trade links. Becker and Muendler [50] investigate the relationship between FDI and employment security, finding that hindering enterprises’ outward FDI leads to more unemployment. Bussy and Zheng [51] argue that rising geopolitical risks and uncertainties hinder FDI. while Aiyar et al. [52] show that geopolitical coordination plays an important economic role in promoting bilateral investment.

Third, the economic analysis of non-economic variables and national security (clusters #3, #6, #11). This area primarily involves research on issues related to climate change, energy security, and human security. Goldberg et al. [53] study the impact of climate change on food security, finding that climate change can affect food systems in multiple ways, including direct impacts on crop production and indirect effects on markets, food prices, and supply chain infrastructure. Barnett and Neil [54] explore the relationship between climate change, human security, and violent conflict, concluding that the direct and indirect impacts of climate change on human security may increase the risk of violent conflict. Regarding energy security, Ang et al. [55] and Radovanović et al. [56] define and measure energy security indices. Additionally, studies have examined the stability of energy supply [57] and price volatility [58,59]. In terms of human security, Wolfendale [60] investigates the impact of terrorism on national security and citizen welfare. Krueger and Jitka [61], and Korotayev et al. [62] study the causal relationship between education and terrorism, finding that higher education levels do not reduce support for violent attacks, and that an increase in years of education in the least educated countries is significantly correlated with an increase in the intensity of terrorist attacks.

Fourth, national security economic analysis in the context of the periods (clusters #0, #1, #2, #12). Most literature on national security economics is analyzed within specific contemporary contexts or based on current practices of various countries. Eventt et al. [63], in the context of current great power industrial policy competition, constructed the Industrial Policy NIPO database and used textual analysis to examine the practices, motivations, and potential impacts of industrial policies in major economies. Ju et al. [64] also concentrate on the Sino-U.S. economic conflict, quantitatively assessing the impacts and interactions of the Sino-U.S. trade war and industrial policy competition. Balbaa et al. [65], in the context of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, study its impact on the world economy, finding that the uncertainty of the conflict, particularly its impact on global supply chains, reduce expectations for global economic growth. Furthermore, sanctions imposed by Western countries on Russia had negative spillover effects on the global economy, contributing to global inflation.

Timeline Analysis of Keywords

Timeline Analysis of Keywords in the China’s Research

Based on the previous analysis on keywords, this paper further employs CiteSpace to generate a timeline of keyword clusters to examine the trends of hotspots over different periods. As shown in Figure 5, the timeline map of the CNKI database from 2015 to 2024 intuitively displays the evolution of research themes. The larger the outer ring, the stronger the centrality of the keyword and the higher the density of keywords, the more research in that period. Based on the start time and duration of each keyword cluster, the research can be divided into the following five categories. First, themes of studies that started early and have a long duration, such as #0 National Security, #1 Sino-U.S. Relations, #3 United States, which have always been hot topics among scholars. Second, themes that started late, have a long duration, and have many recent keywords, such as #2 Great Power Competition, #4 Export Control, which are recent research hotspots that can be further followed. Third, themes that started late, have a long duration, but produce fewer keywords, such as #6 Energy, #8 Sino-U.S. Competition, and #9 Economic Security, are of great importance to scholars but have relatively fewer research outputs. Fourth, themes that started late, have a short duration, but produce many keywords, such as #5 Value Chain, indicating that research related to the value chain was a hot topic in the past but has relatively decreased in recent times. Fifth, themes that started late, have a short duration, and produce few recent keywords, such as #7 Technological Competition, which are recent hot topics worth further attention and discussion.

Based on the timeline in Figure 5, we can further trace the evolution of research paths in national security economics, which has roughly gone through two developmental stages, that is, “2015-2020” and “2021 to present”. It is evident that the evolution of national security economics research over the past decade largely aligns with the terms of successive U.S. presidents and international practices. This indicates that the national security strategies and Sino-U.S. strategic interactions of each U.S. administration have consistently been a focal point of academic interest and a key and important theme.

The “2015-2020” period. This phase primarily coincides with the administrations of Obama and Trump, during which research on national security economics largely aligned with the strategies and actions of the U.S. government, focusing on the following four areas. First, studies on the impact of U.S. investment restrictions on Chinese enterprises, which mainly concentrated in 2019. This was due to the Trump administration’s introduction of the “Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act of 2018 (FIRRMA)” in August 2018, aimed at strengthening regulatory reviews of foreign investment cooperation in the U.S., particularly to increase scrutiny and restrictions on Chinese investments in the U.S. This led to widespread scholarly attention and a gradual increase in research on the impacts of investment restrictions.

Second, research on trade frictions and value chains, which also peaked in 2019, driven by contemporary events that sparked extensive discussions among scholars. Globalization reshaped industrial structures, propelling emerging powers to climb the global value chain and prompting its reconfiguration. Meanwhile, established powers faced increasing domestic deindustrialization, leading to social tensions and external shifts. In 2018, the Trump Administration initiated trade conflicts with major global trading partners, including China, making trade frictions a hot topic in academia during this period.

Third, studies focused on Sino-U.S. relations and strategic competition. The Trump administration’s first “National Security Strategy” declared a new era of great power competition, where interstate strategic rivalry replaced terrorism as the foremost U.S. national security concern, identifying China as a strategic competitor. The strategic competition between China and the U.S. emerged against the backdrop of China’s rapid development and the U.S.’s attempt to maintain its hegemonic status. This competition is significant in terms of interests, long-term in duration, comprehensive in scope, and global in impact. Consequently, discussions on Sino U.S. strategic competition will remain a key topic in academia for an extended period.

Fourth, research on great power technological competition and the securitization of economic issues, which also became prominent around 2020. As China’s technological advancements continued to break through, the U.S. experienced “status anxiety”, justifying its hegemonic behavior in the economic domain by expanding the concept of national security, particularly through comprehensive containment strategies against China in technology and other fields. In 2020, the Trump administration released the “National Strategy for Critical and Emerging Technologies”, outlining the protection of technological advantages in 20 areas, including advanced manufacturing and artificial intelligence, to enhance external competition and maintain global dominance. These U.S. technological containment measures have had negative impacts on international trade and global economic development, attracting widespread scholarly attention.

The “Early 2021 to Present” period. This phase primarily coincides with the Biden administration, during which hotspots in national security economics are closely linked to the strategic measures and international practices of the Biden era, focusing on the following four areas. First, discussions on geopolitics and industrial policies under the backdrop of great power competition. In the era of globalization, as the global industrial competition landscape accelerates its reconstruction, the essence of great power competition has shifted to competition in industrial policies, with strategic industrial security becoming a significant consideration in a country’s national strategy. Consequently, scholars have conducted in-depth explorations of industrial policy competition and its impact on geopolitical patterns under the context of great power competition. Second, economic analyses of deglobalization in academia, with related research averaging in 2021. Deglobalization coexists with globalization, and current scholars have conducted comprehensive analyses and explorations on themes such as the drivers of deglobalization, its impact on global value chains, and socio-economic effects.

Third, studies on technology containment, export controls, and industrial chains, mainly emerging in 2022. In recent years, technology has been one of the most important and prominent challenges in Sino-U.S. strategic competition, with a country’s ability to win in the competition largely depending on its technological innovation capabilities. As China has made rapid progress in the field of science and technology, the U.S. has gradually initiated a series of technological containment measures against China, such as export controls. Since 2017, the U.S. has continuously expanded the number and scope of Chinese entities on its export control entity list, and from an industry distribution perspective, these listed entities have a certain targeting in high-tech fields. Although research on the impact of export controls has long existed, it has mostly focused on micro-level impact analyses. In recent years, the forefront of related research has increasingly focused on the macroeconomic impacts of export controls.

Fourth, analyses of Sino-U.S. strategic games surrounding technological power and technological competition, with such studies averaging in 2023. Sino-U.S. strategic competition and games have been hot topics in academia for nearly a decade, but recent research has mainly focused on the analysis of technological competition between great powers. This primarily involves comparative analyses of competitive strengths and advantages in key technological fields between the two countries, or the identification of key core technologies at the forefront of great power competition through social network analysis based on patent data, analyzing their competitive situations.

It is evident that over the past decade, research on national security economics by Chinese scholars has primarily exhibited three characteristics. First, the research content is closely related to the national security strategies and practices of successive U.S. administrations. Second, the research perspective is mainly based on the context of great power strategic competition, focusing on explaining and analyzing the economic phenomena that arise under this context. Third, there is a greater emphasis on analyzing technological and industrial policy competition under the backdrop of great power rivalry, although current research is limited to theoretical analysis due to data constraints. Therefore, further tracking and discussion of these research topics is warranted, as they represent an important direction for future research.

Timeline Analysis of Keywords in the International Research

Figure 6 presents the timeline of keyword clusters in the WoS from 2002 to 2024. Combining Figure 6 with the keyword clusters, we can further organize the research hotspots. As shown in Figure 6, clusters #0 National Security, #1 Adjustment, and #2 Knowledge Race have consistently been hot topics among foreign scholars, covering key issues such as economic security, energy security, industrial policy, economic adjustment in developing countries, defense expenditure, and conflict. Additionally, issues such as arms race have been a focus of discussion in the international academic community, with a concentration of studies around 2002 and 2020.

As global warming leads to an increase in the frequency of extreme climate events, it has a significant impact on people’s production and daily life. Foreign scholars have gradually begun to quantify the impact of climate change on the global economy and security-related issues. For example, some studies attempt to establish a causal relationship between climate change and violent conflicts, while others discuss the potential impact of climate change on agricultural production and the energy industry, which may threaten economic stability and, in turn, affect national security. Therefore, economic issues related to climate change have become an emerging topic and a hotspot of discussion in the worldwide in recent years. In addition, from 2008 to 2019, economic research on greenhouse gases related to national security was also a hot topic among foreign scholars.

FDI has long been a significant topic of interest for international economists. FDI can bring employment opportunities, promote technological innovation, and stimulate economic growth in the host country, but it can also pose threats to national security. Consequently, foreign scholars have studied both the macro and microeconomic effects of FDI, as well as its implications for national strategy and security. This includes the potential impact of FDI on strategic industries, its effects on a country’s economic security, and how geopolitical factors influence the flow of FDI.

In addition, some clusters of keywords emerged early but generated relatively few keywords and have a small scale, such as #7 Arms Imports and #8 Geopolitical Ecology. The latter, although with fewer formed keywords, has seen three peaks in research, around 2007, 2014-2020, and 2023, which are closely related to the current international situation and practices of various countries. The remaining three clusters, given their limited size and the lukewarm interest from international scholars, will not be delved into further in this analysis.

Research Trends of National Security Economics

National Security Economics and International Trade

International economic relations are, to some extent, a reflection of international political relations, and the state of international economic relations is also reflected in a country’s foreign economic policies. Some trade restrictive measures can be seen as an extension of national security policies, and some national security policies can also be attributed to trade policies. A country may use trade policies to persuade its trading partners to change their behavior, thereby achieving diplomatic goals through trade policy manipulation. As trade links between countries become increasingly close and interdependence grows, trade also acquires externalities related to security. Any event that disrupts trade flows and thereby reduces the welfare of trading countries poses a threat to their national security. Similarly, any action that promotes trade liberalization and brings gains to a country in trade is conducive to national security.

Rational states weigh relative gains and security when formulating foreign policies. Given the high opportunity costs, a country is unlikely to engage in military or diplomatic actions that would disrupt trade order and harm its own social welfare [66]. Of course, trade does not always manifest as positive security externalities. It can also lead to the occurrence of interstate conflicts [67]. Countries facing higher opportunity costs tend to rely more on trade, whereas those with relatively lower opportunity costs may disrupt bilateral trade relations, thereby causing significant social and economic losses to their trading partners. These countries often use trade policies as economic instruments to pursue non-economic goals, employing trade sanctions to enhance their international power status and achieve short-term non-economic objectives. Consequently, in the current context, trade dependence is increasingly being used by hegemonic states as a weapon. By leveraging the asymmetric dependency relationships between countries to launch economic warfare, they aim to contain and suppress rising powers in order to achieve what they call national security [68].

National Security Economics and Industrial Policy

In the context of great power competition, the international environment is increasingly characterized by a close interconnection between economic activities, national security, and foreign policy, leading to the politicization and weaponization of some international economic activities [69-71]. Consequently, some countries adopt economic statecraft strategies, with industrial policies being a key manifestation. Currently, an increasing number of countries are using industrial policies not just to enhance market performance but also to safeguard industrial security and address geopolitical competition, thereby emphasizing their strategic significance.

Economic analyses of industrial policies often focus on specific policy instruments and their economic impacts. For example, studies have examined the global welfare effects of industrial subsidies [72]. However, only a few scholars have analyzed industrial policy competition in the context of great power rivalry, where such policies can lead to spillover effects, trade tensions, and retaliatory actions from other countries [73]. Bown [74] and Goldberg et al. [75] suggest that domestic subsidies can alter international competitive environments through trade, prompting other governments to retaliate and potentially leading to subsidy wars. Evenett et al. [63] confirmed these findings, noting that industrial policies can have negative spillover effects on trading partners, with 75% of such policies causing trade distortions. Additionally, long-term industrial policies must continuously adapt to changes in domestic and international situations, emphasizing coordination and consistency with macroeconomic policies [76,77]. Given the limited research in this area, further exploration of national security economics and industrial policies in the context of great power competition is warranted.

National Security Economics and Technology Competition

Technology is an endogenous driving force for global political and economic development. Major powers enhance their economic capabilities through continuous technological innovation to promote industrial structure upgrading, which in turn provides them with strong bargaining power and competitiveness in the contest for economic privileges [78]. Currently, technological competition and the reconstruction of global value chains have become increasingly important and prominent aspects of global economic interactions. Even in the context of the broadening of economic security, they cannot be divorced from national security [79]. The Biden Administration’s 2022 National Security Strategy also pointed out that “technology is the core of today’s geopolitical and geo-economic competition, as well as the core of national economic security. Future key and emerging technologies will reshape the world’s economic, military, and political landscape.”

Consequently, technological innovation plays a crucial role in the interactions among major powers, and securing a technological lead in strategically competitive industries has become the high ground in the Sino-U.S. strategic competition. The U.S. government has also initiated a new Cold War against China, regarding China as its primary adversary in geopolitical and technological aspects [80]. Triolo [81] found that as Sino-U.S. economic and trade relations developed, long-term cooperation between the two countries was locked into advanced technologies, and competition between them led to technological decoupling. Khan et al. [82] discussed the causal relationship between geopolitical risks and technology, finding that divergent national interests drive technological competition and that geopolitical risks enhance a country’s technological level. Against the backdrop of great power competition, technology is a key driving factor for economic, political, and military power, and is also at the forefront and center of current Sino-U.S. strategic competition. It will significantly alter the future economic operations and national security status, posing a challenge to global stability. Discussions on the power transition between China and the U.S. have also sparked academic debates on great power technological competition, with many scholars recognizing that technological capabilities are becoming increasingly important factors in a country’s overall strength [83].

Mechanism Analysis of Potential Casual Mechanism

Further, the bibliometric method based on CiteSpace primarily relies on keyword co-occurrence maps, clustering maps, and timeline maps to reveal the evolution and intrinsic connections among research themes. These visualizations allow for the inference of potential causal mechanism.

First, in the keyword co-occurrence map, each node represents a keyword. Its frequency shows the keyword’s importance in the field. Betweenness centrality reflects a node’s importance in the network, measures this significance. It not only has statistical significance but also helps identify and infer potential causal pathways among keywords or themes, which is often overlooked in traditional CiteSpace-based bibliometric research. From a causal inference perspective, a high betweenness centrality suggests the keyword may be a key mechanism connecting two research themes, aiding new theory development. Second, the keyword clustering timeline graph shows the evolution of keyword clusters over time and can reveal potential causal relationships based on their emergence order. For example, if one keyword cluster appears earlier than another, it might influence the latter. However, rigorous causal inference needs econometric validation.

Using these graphs, we can identify common causal mechanism in the economics of national security, such as those between national security and export controls, Sino-U.S. relations and geopolitics, and climate change and energy security. These have been recognized and tested in existing literature. We can also find some potential causal mechanism with theoretical foundations but not yet empirically validated. For instance, as the Figure 5 shows, the cluster of Sino-U.S. relations is linked to the clusters of securitization and technological power. Since the Sino-U.S. relations cluster formed earlier and later intersected with the technological power cluster, we can infer that research on Sino-U.S. relations has driven studies on the causal mechanism of technological power competition between the two. Realism posits that in an anarchic international system, the great power pursues power maximization to secure its dominance [84]. The technological competition between China and the United States fundamentally reflects a struggle for techno-power between a rising challenger and an incumbent hegemon—an inevitable manifestation of structural contradictions arising from U.S. hegemonic preservation and China’s ascendance [83,85].

As shown in Figure 6, industrial policy formed a separate cluster later than national security, and the two are associated. This implies industrial policy is becoming a driver for national security. In today’s globalized world with deepening economic interdependence, hegemons turn economic reliance into political coercion [68]. Currently, key industries such as semiconductors face security threats. To address these challenges, major powers use industrial policies to control key industrial chains and supply chains and weaponize them for policy competition with other major powers [86,87].

Conclusion

In recent years, from climate change to global pandemics, from regional conflicts to national strategic competition, countries around the world have increasingly placed national security issues on a more prominent and important position. How are the research hotspots in national security economics? What are the differences between China and the worldwide? Are there exist any potential causal mechanism among the research themes?

In light of this, this paper systematically combs and summarizes the literature on national security economics using bibliometric methods and CiteSpace tools, based on the CNKI and WoS databases. Through keyword co-occurrence analysis, keyword clustering analysis, and keyword clustering timeline diagrams, it analyzes the hotspots in different periods, constructs a knowledge map, discusses the differences between China and worldwide, and looks forward to future research trends. The main conclusions are as follows.

First, through the analysis of keyword co-occurrence, we can identify the hotspots in national security economics. Initially, the hotspots in China’s research are primarily focused on national security, Sino-U.S. relations, and great power competition, with Sino-U.S. relations having a high centrality among various research themes, indicating a strong internal connection in the study of national security economics. Subsequently, the hotspots from the worldwide are mainly concentrated on national security, economic growth, and foreign direct investment, with research on themes such as conflict, climate change, defense economics, export controls, and industrial policies also being hot directions in recent years.

Second, through the analysis of keyword clustering, we can also identify the key areas of the research. According to the keyword clustering map, issues related to national security such as great power technological competition and Sino-U.S. strategic competition, issues related to Sino-U.S. relations such as trade policy, securitization, and technological containment, and issues related to great power competition such as geopolitics, industrial policy, and economic sanctions are the key issues studied by Chinese scholars. In addition, issues related to national security, economic adjustment, and knowledge competition are also key areas of research for international scholars.

Third, through the analysis of the keyword clustering timeline, we can further identify the trends in the research. In terms of China’s research, it has roughly gone through two developmental stages “2015—2020” and “2021 to present”. The research evolution stages in China over the past decade have largely coincided with the terms of U.S. presidents, indicating that the strategic interactions between China and the U.S. are an important direction. In the international research aspect, issues related to national security, economic adjustment, knowledge competition, and foreign direct investment have always been key areas of research, while issues such as arms races, climate change, greenhouse gases, weapons imports, and geopolitical ecology have certain period-specific characteristics.

Fourth, based on the analysis of research differences, we find that the literature on national security economics in the CNKI database mainly focuses on the strategic game between China and the U.S., with significant relevance to the U.S. government’s national security strategy and international situation. In contrast, the research scope of WoS scholars is broader, often starting from the concept of national security and the contemporary background of interactive practices among major economies. Additionally, this paper summarizes and analyzes the frontiers of future research from three aspects, that is, national security economics and international trade, industrial policy, and technological competition. Overall, under the current context of great power competition, the theoretical analysis of national security economics is already quite rich, but it lacks quantitative analysis and empirical testing, which need to be further expanded in the future.

Fifth, based on the keyword co-occurrence and keyword clustering timeline analysis, we can identify potential causal mechanism between keywords by analyzing betweenness centrality, chronological order, and trend intersections. In this paper, we focus on the potential causal mechanism among Sino-U.S. relations, securitization, technological power, as well as the latent causal pathways between national security and industrial policy, integrating realism and the theory of weaponized interdependence.

Appendix A

Considering that, the CiteSpace has limitations. Specifically, it outputs maps in Chinese when the data source is Chinese database. Thus, this paper provides Chinese-English glossary for figures presented in Chinese in the main text, such as Figure 1, Figure 3, Figure 5, as shown in Table A1.

Acknowledgment in the Funding Section:

This work was supported by the Strategic Economy Interdisciplinarity (Beijing Universities Advanced Disciplines Initiative, No. GJJ2019163)

Competing Interest:

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

References

Coulomb, F. (1998). Adam smith: A defence economist. Defence and Peace Economics, 9(3): 299–316. View

Hummel, J.R. (1990). National goods versus public goods: Defense, disarmament, and free riders. The Review of Austrian Economics, 4(1):88-122. View

Hummel, J.R. & Lavoie, D. (1994). National Defense and the Public-Goods Problem. Journal des economistes et des études humaines, 5(2-3): 353-378.View

Walt, S.M. (2010). Realism and security. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of International Studies. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of International Studies. View

McMillan, S.M. (1997). Interdependence and conflict. Mershon International Studies Review, 41(1):33-58. View

Polachek, S.W., Robst, J., Chang, Y.C. (1999). Liberalism and interdependence: Extending the trade-conflict model. Journal of Peace Research, 36(4):405-422. View

Burchill, S. (2005). Liberalism. Theories of international relations, 3, 55-83.View

Varadarajan, L. (2004). Constructivism, identity and neoliberal (in) security. Review of International Studies, 30(3):319-341. View

Reus, S. C. (2005). Constructivism. Theories of international relations, 3, 188-212.View

Mastanduno, M. (1999). Economic statecraft, interdependence, and national security: agendas for research. Security Studies, 9(1-2): 288-316. View

Baldwin, D. A. (2020). Economic statecraft: New edition, Princeton University Press.View

Lincoln, G. A., William, S. S., Thomas, H. H. (1950). Economics of national security, Cambridge University Press. View

Hitch, C. J. (1960). National security policy as a field for economics research. World Politics, 12(3): 434-452. View

Dunne, J. P. (2007). The Changing Economics of Security, 1-23. View

Luciani, G. (1988). The Economic Content of Security. Journal of Public policy, 8(2): 151-173. View

Friedberg, A. L. (1991). Power, Economics, And Security, Oxford University Press. View

Kapstein, E. B. (2002). Two Dismal Sciences Are Better Than One--Economics and the Study of National Security: A Review Essay. International Security, 27(3): 158-187. View

Engerer, H. (2009). Security economics: Definition and capacity. Economics of Security Working Paper, 1-30. View

Giglio, F. (2021). Fintech: A literature review. European Research Studies Journal, 24(2B): 600-627. View

Żuk, P. & Żuk, P. (2022). National energy security or acceleration of transition? Energy policy after the war in Ukraine. Joule, 6(4):709-712. View

Von, U. N.& Buhaug, H. (2021). Security implications of climate change: A decade of scientific progress. Journal of Peace Research, 58(1):3-17. View

Iftikhar, A., Ali, I., Arslan, A., Tarba, S., (2024). Digital innovation, data analytics, and supply chain resiliency: A bibliometric-based systematic literature review. Annals of Operations Research, 333(2):825-848. View

Bednarski, L., Roscoe, S., Blome, C., Schleper, M.C. (2025). Geopolitical disruptions in global supply chains: a state-of-the-art literature review. Production planning & control, 36(4):536-562. View

Zhang, Z., Ning, H., Shi, F., et al. (2022). Artificial intelligence in cyber security: research advances, challenges, and opportunities. Artificial Intelligence Review, 1-25. View

Kokol, P., Blažun, V. H., Završnik, J. (2021). Application of bibliometrics in medicine: a historical bibliometrics analysis. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 38(2): 125-138. View

Liu, X., Zhao, S., Tan, L.L., Tan, Y., Wang Y., Ye, Z.Y., Hou, C.J., Xu, Y., Liu, S., Wang, G.X. (2022). Frontier and hot topics in electrochemiluminescence sensing technology based on CiteSpace bibliometric analysis. Biosensors and Bioelectronics, 201,113932. View

Wei, J., Liang, G., Alex, J., Zhang, T., Ma, C. (2020). Research Progress of Energy Utilization of Agricultural Waste in China: Bibliometric Analysis by CiteSpace. Sustainability, 12(3):812. View

Kut, P., & Pietrucha-Urbanik, K. (2024). Bibliometric Analysis of Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM) Methods in Environmental and Energy Engineering Using CiteSpace Software: Identification of Key Research Trends and Patterns of International Cooperation. Energies, 17(16): 3941. View

Zhou, W., Aiqing, K., Jin, C., Bingqing, D. (2018). A retrospective analysis with bibliometric of energy security in 2000–2017. Energy Reports, 4, 724-732. View

Jiang, Y., & Liu, X. (2023). A Bibliometric Analysis and Disruptive Innovation Evaluation for the Field of Energy Security. Sustainability,15(2):969. View

Sharifi, A., Simangan, D., Kaneko, S. (2021). Three decades of research on climate change and peace: a bibliometrics analysis, 16,1079–1095. View

Zabavnik, D., & Miroslav, V. (2021). Relationship between the financial and the real economy: A bibliometric analysis. International review of economics & finance, 75,55-75. View

Sandip, S., Achuta, R. P., Seema, S. (2023). Exploring the dynamics of defense expenditure and economic development: A bibliometric analysis. International Journal of Business and Society, 24(3): 1314–1343. View

Mowery, D. C. (2009). National security and national innovation systems. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 34(5): 455-473. View

Yildirim, J., Selami, S., Nadir, Ö. (2005). Military expenditure and economic growth in Middle Eastern countries: A dynamic panel data analysis. Defence and Peace Economics, 16(4): 283 295. View

Yildirim, J., & Öcal, N. (2016). Military Expenditures, Economic Growth and Spatial Spillovers. Defence and Peace Economics, 27(1): 87-104. View

Azam, M., Khan, F., Zaman, K., Rasli, A. M. (2016). Military expenditures and unemployment nexus for selected South Asian countries. Social indicators research, 127, 1103-1117. View

Christensen, J. (2015). Weapons, Security, and Oppression: A Normative Study of International Arms Transfers. Journal of Political Philosophy, 23(1): 23-39. View

Kang, S., & Meernik, J. (2015). Civil war destruction and the prospects for economic growth. The Journal of Politics, 67(1): 88-109. View

Minhas, S., & Radford, B. J. (2017). Enemy at the gates: Variation in economic growth from civil conflict. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 61(10): 2105-2129. View

Osgood, I., & Simonelli, C. (2020). Nowhere to go: FDI, terror, and market-specific assets. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 64(9): 1584-1611. View

Powers, M., & Choi, S.W. (2021). Does transnational terrorism reduce foreign direct investment? Business-related versus non-business-related terrorism. Journal of Peace Research, 49(3):407-422. View

Mirza, D., & Thierry, V. (2008). International trade, security and transnational terrorism: Theory and a survey of empirics. Journal of Comparative Economics, 36(2): 179-194. View

Collier, P., & Duponchel, M. (2013). The economic legacy of civil war: firm-level evidence from Sierra Leone. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 57(1): 65-88. View

Chamarbagwala, R., & Morán, H. E. (2011). The human capital consequences of civil war: Evidence from Guatemala. Journal of Development Economics, 94(1): 41-61. View

Lai, B., & Thyne, C. (2007). The effect of civil war on education, 1980—97. Journal of Peace Research, 44(3): 277-292. View

Coutts, A. (2024). The age of consequences: Unraveling conflict’s impact on social preferences, norm enforcement, and risk-taking. Journal of Economic Behavior Organization, 218, 48-67. View

Glick, R., & Taylor, A. M. (2010). Collateral damage: Trade disruption and the economic impact of war. The Review of Economics Statistics, 92(1): 102-127. View

Rosecrance, R., & Thompson, P. (2003). Trade, foreign investment, and security. Annual Review of Political Science, 6(1): 377-398. View

Becker, S. O., & Muendler, M. (2008). The Effect of FDI on Job Security. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 8(1):1-46. View

Bussy, A., & Huanhuan, Z. (2023). Responses of FDI to geopolitical risks: The role of governance, information, and technology. International Business Review, 32(4): 102136. View

Aiyar, S., Davide, M., Andrea, F. P. (2024). Investing in friends: The role of geopolitical alignment in FDI flows. European Journal of Political Economy, 83, 102508. View

Goldberg, P. K., Juhász, R., Lane, N. J., Forte, G. L., Thurk, J. (2024). Industrial policy in the global semiconductor sector (No. w32651). National Bureau of Economic Research. View

Barnett, J., & Neil, A. (2007). Climate change, human security and violent conflict. Political Geography, 26(6): 639-655. View

Ang, B. W., Wei, L. C., Tsan, S. N. (2015). Energy security: Definitions, dimensions and indexes. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 42, 1077-1093. View

Radovanović, M., Sanja, F., Dejan, P. (2017). Energy security measurement–A sustainable approach. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 68, 1020-1032. View

Shaffer, B. (2013). Natural gas supply stability and foreign policy. Energy Policy, 56, 114-125. View

Kilian, L. (2008). The economic effects of energy price shocks. Journal of Economic Literature, 46(4): 871-909. View

Chen, Z. M., Chen, P. L., Ma, Z., Xu, S., Hayat, T., Alsaedi, A. (2019). Inflationary and distributional effects of fossil energy price fluctuation on the Chinese economy. Energy, 187, 115974. View

Wolfendale, J. (2006). Terrorism, Security, and the Threat of Counterterrorism. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 30(1):75–92. View

Krueger, A. B., & Jitka, M. (2003). Education, Poverty and Terrorism: Is There a Causal Connection? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17 (4): 119–144. View

Korotayev, A., Vaskin, I., Tsirel, S. (2019). Economic Growth, Education, and Terrorism: A Re-Analysis. Terrorism and Political Violence, 33(3): 572–595. View

Evenett, S., Jakubik, A. M., Fernando, Ruta, Michele. (2024). The Return of Industrial Policy in Data. IMF Working Paper, 1-31.View

Ju, J., Ma, H., Wang, Z., Zhu, X. (2024). Trade wars and industrial policy competitions: Understanding the US-China economic conflicts. Journal of Monetary Economics, 141, 42-58. View

Balbaa, M. E., Eshov, M. P., Ismailova, N. (2022). The Impacts of Russian Ukrainian War on the Global Economy in the frame of digital banking networks and cyber-attacks. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Future Networks & Distributed Systems, 137-146.View

Levy, J. S. (2023). Economic interdependence, opportunity costs, and peace. Economic Interdependence International Conflict: new perspectives on an enduring debate, 127-147. View

Rosecrance, R., & Peter, T. (2023). Trade, foreign investment, and security. Annual Review of Political Science, 6(1): 377-398. View

Farrell, H., & Newman, A. L. (2019). Weaponized interdependence: How global economic networks shape state coercion. International Security, 44(1): 42-79. View

Hasnat, B. (2015). US national security and foreign direct investment. Thunderbird International Business Review, 57(3): 185-196.View

Moisio, S. (2018). Towards geopolitical analysis of geoeconomic processes. Geopolitics, 23(1): 22-29. View

Thirlwell, M. P. (2010). Return of Geo-economics: Globalisation and National Security. Lowy Institute for International Policy Sydney,43.View

Lashkaripour, A., & Lugovskyy, V. (2023). Profits, scale economies, and the gains from trade and industrial policy. American Economic Review, 113(10): 2759-2808. View

Rotunno, L., & Ruta, M. (2024). Trade Implications of China’s Subsidies. IMF working paper, 1-61. View

Bown, C. P. (2023). Modern industrial policy and the WTO. Peterson Institute for International Economics Working Paper, 23-15. View

Gregory, P. J., Ingram, J. S., Brklacich, M. (2005). Climate change and food security. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 360(1463): 2139-2148. View

Chang, H. J., & Antonio, A. (2020). Industrial policy in the 21st century. Development and Change, 51(2): 324-351. View

Oqubay, A., Cramer, C., Chang, H. J., Kozul-Wright, R. (2020). The Oxford handbook of industrial policy, Oxford Press. View

Wu, X. (2020). Technology, power, and uncontrolled great power strategic competition between China and the United States. China International Strategy Review, 2(1): 99-119. View

Glenn, R. W. (2018). New Directions in Strategic Thinking 2.0. ANU Strategic & Defence Studies Centre’s Golden Anniversary Conference Proceedings, ANU Press. View

Yao, Y. (2021). The new cold war: America’s new approach to Sino-American relations. China International Strategy Review, 3(1): 20-33. View

Triolo, P. (2019). Geopolitics and technology U.S.-China competition: The coming decoupling? RSIS Commentaries, 214. View

Khan, K., Su, C. W., Umar, M., Zhang, W. (2022). Geopolitics of technology: A new battleground? Technological and Economic Development of Economy, 28(2): 442-462. View

Ding, J. (2024). The diffusion deficit in scientific and technological power: re-assessing China’s rise. Review of International Political Economy, 31(1): 173–198. View

Mearsheimer, J.J. (2021). The inevitable rivalry: America, China, and the tragedy of great-power politics. Foreign Aff., 100, 48. View

Wu, X. (2020). Technology, power, and uncontrolled great power strategic competition between China and the United States. China International Strategy Review, 2(1):99-119. View

Juhász, R., Lane, N., Rodrik, D. (2023). The new economics of industrial policy. Annual Review of Economics, 16, 213-242. View

Bulfone, F. (2023). Industrial policy and comparative political economy: A literature review and research agenda. Competition & change, 27(1): 22-43. View