Journal of Political Science and Public Opinion Vol. 3 iss. 1 (Jan-Jun) (2025), Article ID: JPSPO-119

https://doi.org/10.33790/jpspo1100119Research Article

Finding Common Ground: The Foundation of Community

Theresa Marchant-Shapiro*, and Andrew Marchant-Shapiro

Southern Connecticut State University, 501 Crescent Street, New Haven, United States.

Corresponding Author: Theresa Marchant-Shapiro, Professor, Department of Political Science, Southern Connecticut State University, 501 Crescent Street, New Haven, United States.

Received date: 13th February, 2025

Accepted date: 29th April, 2025

Published date: 01st May, 2025

Citation: Marchant-Shapiro, T., & Marchant-Shapiro, A., (2025). Finding Common Ground: The Foundation of Community. J Poli Sci Publi Opin, 3(1): 119.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Abstract

The concept of community is at the heart of discussions about democracy and political efficacy. The question for this research project is how civil society organizations go about developing a sense of community among their members. This paper takes a qualitative case study approach to analyzing a community organization in an urban setting. Books and Company is a small bookstore in Hamden, Connecticut, that places community building at the heart of its mission. By interviewing the owner and frequenters of the store, we address the techniques this organization has used to build and strengthen community and to empower those who frequent it. In the face of increasing conflict at the local, national, and international levels, understanding how communities come together has the potential to establish a foundation to bridge divides.

Introduction

Almost two centuries ago in 1831, a young French noble, Alexis de Tocqueville, set off from France with his friend Gustave de Beaumont. The pair had been commissioned by the French government to report on the prison system in America. But de Tocqueville had bigger plans for the trip. In addition to touring the major prisons of the day, the pair also took the time to meet with Americans, some of whom were well-known (former president John Quincy Adams, Sam Houston, current President Andrew Jackson), but most of whom were not. De Tocqueville had been born to an aristocratic family still reeling from the French Revolution. Although he saw democracy as inevitable, he wanted to make its manifestation in France more stable. His trip to the United States was an opportunity to study a stable version of democracy in hopes of taking the lessons he learned home to France.

One of de Tocqueville’s [1] major takeaways was that democracy worked in the United States because of the ubiquity of voluntary organizations. Whereas Europeans relied on the wealth of the aristocracy to solve social problems, he saw Americans, when confronted with a collective need, forming voluntary associations and working together to achieve their goals. He concluded that American democracy was stable because its reliance on such associations inculcated a sense of equality and encouraged political engagement.

De Tocqueville’s depiction of voluntary organizations formed the basis of our modern understanding of civil society as the space between an individual and the state. 20th century pluralists based their praise of this middle space on the understanding that groups, not individuals, perform vital roles in democracy. In part, this can be attributed to their focus on stability [2]. This is not to deny the individual impact that groups can have in teaching the kinds of skills relevant to social capital and through it on democracy. As with E. E. Schattschneider’s [3] observation that “the flaw in the pluralist heaven is that the heavenly chorus sings with an upper-class accent,” identifying groups as the foundation of civil society privileges the already empowered [4,5]. But regardless of that privilege, the importance of voluntary associations has remained central to American political thought.

De Tocqueville’s explanation of the political importance of voluntary organizations reverberated in the 1980s in international support for civil society organizations. In the face of authoritarian regimes in Eastern Europe and Latin America, non-governmental actors organized to push for political change [6]. Since then, it has become commonplace for political organizations (such as the UN, the EU, OECD, World Bank and so forth) to couch their efforts to support freedom and democracy in terms of “structures that seek to support civil society.” The general belief is that such organizations are essential to build free societies.

In the face of widespread acceptance of the notion that voluntary organizations form a necessary foundation for democracy, it was with grave concern that political scientist Robert Putnam [7] found them beginning to decline in the United States in the 1980s and 1990s. The trajectory that he documented in Bowling Alone has accelerated. Since then, American men, unmarried adults, and teens ages 15-19 have reduced the time they spend in face-to-face socializing by 30 percent, 35 percent, and 45 percent respectively [8]. At one level, the consequences are personal: Loneliness, depression, and anxiety have increased to record highs [9]. The trend began well before the COVID pandemic, with the growth of social media and virtual interaction, but was certainly exacerbated by it, with Surgeon General Vivek Murthy calling loneliness “an epidemic” that poses a significant public health threat [10].

The consequences are not only personal; they are also social. For example, the trend has included a decline in church attendance and membership. Whereas throughout the 20th Century, around 70% of Americans reported belonging to a church, synagogue, or mosque [11], by 2021 membership declined to less than 50% [12]. The decline of this major aspect of civil society has had the consequences that de Tocqueville and Putnam would have predicted: Those Americans who no longer think of themselves as church members are much less likely to be politically engaged than other Americans. Specifically, in addition to being more likely to feel lonely, they are also less likely to vote, to volunteer, and to be satisfied with their local community [13].

We come to our research concerned about the decline in political participation, the deterioration of civil society, and the fading of social connectedness that is at the root of the problem. What can be done to reverse the trend? How do we go about building community? To answer these questions, we conducted a case study of a local bookstore where relationships thrive. Although generally accepted definitions of civil society organizations exclude businesses, in our individual lives, community can be built anywhere people come together.

Thus, a business (especially a small local business) can become a “third place”—a location other than home or work where people come together, a place that can serve as an anchor for the community by hosting frequent informal gatherings of residents who otherwise might not meet or interact [14]. Such spaces serve as incubators for relationships within communities—building relationships that can be transformed into social capital and civil society.

Community and Society

Over the past thirty years, and particularly since the period of isolation brought about by the COVID pandemic, we have seen an increasing concern with the impact of loneliness on human behavior. As the population of the United States has grown, it has simultaneously become increasingly disconnected and rootless. If, as Ira Katznelson argued in City Trenches (1981), cross-cutting workplace and residential political spheres once immobilized the American working class, a parallel sort of individual disengagement from civic life began in the 1970s.

Some viewed the withdrawal from social engagement as a necessary counterpart to the turmoil of the prior decade. In Candide [15] Voltaire tells us that we must each tend our own garden and, indeed, the 1970s were often hailed as the “me” decade, as interior and spiritual concerns seemed to replace societal. But half a century later, we are beginning to see the consequences of a longer-term turn from public life. Disengagement has led to distrust, and that distrust has led, not monotonically but increasingly, to the popularity and electability of candidates who themselves see our sociopolitical system as less than legitimate. Whether encompassed in Ronald Reagan’s jibe that “The nine most terrifying words in the English language are: I'm from the Government, and I'm here to help” (News Conference, August 12, 1986) or Donald Trump’s (2016 and 2024) promises to “drain the swamp,” appeals by charismatic “outsiders” to “outsider” electors who distrust our system [16] is concerning. What, then, has reduced us all to “outsider” status?

The Impact of Society on Community

Sociologists have long been fascinated with what they saw as the modernizing movement from simplicity to complexity. Emile Durkheim focused on the transition from a civilization in which most people are fundamentally similar to one another, as if mass- produced parts (what he termed mechanical solidarity) to one in which individuals differentiate and specialize, filling different and (importantly) interdependent roles (his organic solidarity). One might broadly conceptualize this as the transition from subsistence farming to an economy where some people farm, some people engage in manufacture, others practice law, and the lawyer (for example) need not go home to tend the cattle.

In a related vein, Ferdinand Tönnies analytically [17] counterposed Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft—typically translated as community and society. The former is the older mode of interaction, closely associated with Durkheim’s mechanical solidarity. In such a setting, as Waters [18] writes, “Gemeinschaft-based relationships tend to be affectual, while Gesellschaft relationships tend to be instrumental.” While the former is characterized by a solidarity based on emotion, the latter is mediated by money.1

Thus in contemplating the relationship between the older community and the evolving society we often picture the former as characterized by rural villages and (sometimes) urban ghettos, but principally by a kind of undifferentiated mass. Like paperclips in a drawer, individuals in a Gemeinschaft partake of mechanical solidarity. Society, on the other hand and, is all about urbane urbanism—freedom to experiment and to participate in the organic solidarity that differentiates a modern civilization from a collection of mud huts.

Acknowledging that this characterization is more than a little tongue in cheek, it may be worthwhile to turn from the business of merely contrasting community and society toward considering instead their chronological relationship. If we do that, it seems clear that if society can be said to have a foundation, then that foundation can only be located in the mud huts of community.

Yet is nearly axiomatic that, in the face of modern society, community has been undercut. From Bowling Alone to the decline in religious participation, we seem to see increasingly the dissolution of the very communal ties that once enabled us to build nations.2 Society has become too large, too domineering. Even at the cultural level, we no longer communally partake of the 6:00 evening news broadcast or read the same morning paper; instead, everyone is free to “browse alone.”

Where Everybody Knows Your Name (Without Cookies)

The same processes that have led us to specialized (virtually individualized) consumption of news and opinion, namely the replacement of mechanical by organic solidarity, have created in parallel a world in which many of our interactions with human beings (outside of workplace and family) are stochastic. Barristas are interchangeable. Store clerks and cash register operators and waiters—in all of these cases, the role being performed is more important than the person performing it. The same is true, from a customer’s perspective, of the organizations that we interact with. Organic solidarity necessarily leads to specialization, but (at least in a market economy) that same specialization leads to fungibility. Starbucks and Peet’s Coffee, for example, McDonald’s and Burger King, Walgreen’s and CVS. Within each pair, either can supply coffee, either can supply burgers, either can fill your prescription. The organizations that fill each of these specialized roles seek to distinguish themselves one from another. But they are ultimately interchangeable with others in the same category (coffee, fast food, drug stores). These are large places.

Late in the 19th century, Lafcadio Hearn published a translation of a Japanese folk tale titled “The Boy Who Drew Cats.” Advice given to the titular boy is crucial to the story: “Avoid large places;3 keep to small.” If society is a large place, then perhaps it behooves us to look for community in the small. In the “third place.” The theme song from the sitcom Cheers (1982-1993) tells us that:

Sometimes you want to go

Where everybody knows your name

And they're always glad you came

You want to be where you can see

Our troubles are all the same

You want to be where everybody knows your name.

The Cheers bar is an example of Oldenberg’s (1989) “third place.” Third places, as opposed to Gesellschaftian organizations, are emphatically not fungible. They can generally have the following characteristics:

• Third places are neutral ground that people frequent voluntarily;

• Because interactions in third places ignore external status, they are egalitarian in nature;

• In third places, light-hearted conversation is the main activity;

• Third places are accessible to, and accommodating toward, their habitues;

• In third places, “regulars” play an important role in creating a welcoming environment;

• Third places are generally characterized by a playful mood, where banter is highly valued;

• Third places provide a sense of belonging.

Building Community in Books and Company

In 1995, America discovered the Internet. In 1995, a Seattle startup specializing in selling books changed its name from “Cadabra” to “Amazon.” And in 1995, a transplant from the San Francisco Bay area opened Books and Company, a used bookstore and café in Hamden, Connecticut.

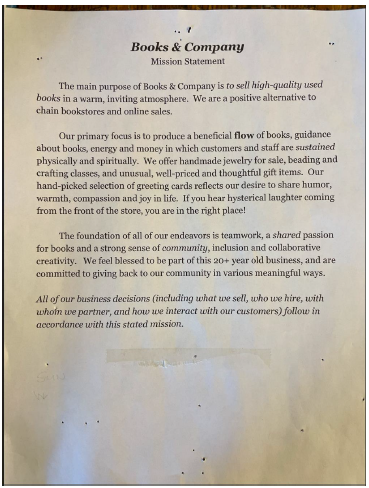

On a corkboard behind the bookstore’s cash register is pinned a yellowing mission statement:

Since 1999, Books and Company has been a neighborhood fixture. In 2009, the owner, Linda M., partnered with Teresa F., owner of Legal Grounds, a displaced local coffee shop then in search of new space. Legal Grounds took over the café duties in the back of the bookstore. In keeping with the mission statement of Books and Company, Legal Grounds sees itself as an inclusive community oriented business. While the two are separate economic enterprises, they are partners, spatially intertwined, and for most purposes we treat them as a single entity.

Books and Company clearly qualifies as a third space under Oldenberg’s criteria: Nobody is obliged to go to this bookstore for either books or coffee (Barnes and Noble is not far away). But if they do walk into Books and Company, regardless of status, clothing, or age, they find themselves on equal footing with the regulars—and addressed by name. Both the staff and the regulars make a point of learning as soon as possible who people are and where they come from.

Regulars include arborists, bureaucrats, engineers, environmental scientists, deadheads, employees of the town’s public works department, users of the nearby bus stop, professional photographers, yoga teachers, historians, artists, attorneys, social workers, retirees, college and high school students, and neighbors. Regulars may (or may not) be customers of either of the businesses. (One person regularly simply stops by to use the bookstore’s restroom while in between bus lines. He, too, is known and greeted by name). While most of the regulars live within a few miles of Books and Company, they are not geographically concentrated.

There is generally (but not universally) a liberal/left lean to the politics of the employees and the regulars, similar to that of the neighborhood. While the talk—and there is a lot of talk—can turn serious from time to time, particularly around elections, humor (often political) is prized, and it is rare for a regular to take (and perhaps more importantly, give) offense. One employee regularly teams up with a particular habitue to collect memes for posting at the rear entrance. Finally, the atmosphere is as home-like as possible, and the store generally has at least one canine occupant (Linda’s tiny poodle Lily recently died; Teresa’s dog Lucy known by the regulars as Lucifer) presently holds things down in the Legal Grounds area. Prior to COVID, the bookstore hosted and managed a neighborhood fall festival. Both before and after the pandemic, the bookstore hosted book clubs, gardening clubs, lessons in knitting and other fabric arts, and served as an office for office-less co-workers.

Last year one of the employees expressed anxiety regarding being alone in the shop on Friday afternoons after the coffee shop closed. In response a pair of regulars committed to bringing their guitars in during that period for a jam session at the back of the store. This has grown to include four guitars, a drum, a harmonica and a fluctuating group of vocalists in a full-on afternoon’s entertainment.

Crucially, one of the ways that the bookstore fosters this kind of behavior is simply by not charging for the use of the space. It provides an environment in which informal conversation has led to activities. Many of these would continue even if Books and Company burned to the ground—but they would not have begun without the incubating environment the bookstore provides gratis.

A word is in order here regarding Oldenberg’s “accommodation” criterion. When COVID struck Connecticut, stores like Books and Company were necessarily forced to close their doors. But beginning with the second month of the shutdown, the bookstore posted photos of its wares online, and customers could call or email the shop with “concierge” requests, whether for books, toys, bags, or other needs. A masked concierge would bring purchases to the door. Legal Grounds began accepting phone orders, coffee being carefully placed in disposable cups on the back steps of the shop, payments made by credit card or accounts kept. (Even before the pandemic, Legal Grounds allowed customers to set up prepaid accounts against which to charge their orders, and this probably eased the transition into pandemic mode somewhat).

Most importantly, during the first months of the pandemic, Linda, Teresa, and Fran (the bookstore manager) used their skills as fabric artists to manufacture multi-layered cloth masks in sizes for adults and children at a time when medical masks were all but unattainable. These masks were sold for $3-5, depending on size. In this way, Books and Company literally took care of its regulars, of its community.

Regulars also take care of one another. Near the front door is a bookshelf originally intended to help the bookstore rid itself of books that didn’t fit its market. The shelf was initially loaded with books free for the taking—frequently unsaleable donations to the store. But over time, regulars (and others) began to bring in reading glasses, unused notebooks and pens, folders, bags, and small (and sometimes large) electronics. These are all free for those who can use them.

Because Books and Company has regulars, it also provides a crucial forum for the exchange of information à la Mark Granovetter’s [19] work on the strength of weak ties. This operates in two related fashions. First, there is direct peer-to-peer exchange, in the sense that regular A mentions to regular B that they need a particular good or service, or recommendation, and regular B supplies the needed information. Or B will know someone who can help A. Alternatively, the information may pass through shop staff. In general, staff will have a wider range of knowledge about the regulars. If you’re having a problem with a sewing machine, the barista is likely to know that one of the regulars is a sailmaker with extensive knowledge of sewing machines. Need a plumber? A painter? A mechanic? Regulars and staff alike will be happy to recommend people they trust. And, importantly, regulars and staff trust each other.

Trust emerges from daily exchanges and banter within the shop. Face-to-face interactions generally carry more weight than on-line interactions or advertising on social media. Regulars in third places like Books and Company are also, due to this trust, willing to share tools and work. When bulbs in a storeroom fixture needed replacing, one regular replaced them while another held the ladder.

Long-term regulars talk about the time early in the last decade when a speeding car crashed through the front window of the shop and plowed its way nearly to the rear wall. While the driver and passengers escaped uninjured, the store lost inventory and required extensive repairs. Regulars showed up immediately to assist where they could, carrying wreckage out and new stock in. As Linda described, “Even when the crash happened—a friend from the apartments next door came in with lemonade and I forget what all else to offer to us as we were assessing the damage.” With everyone chipping in, the store was back in full operation within a few weeks. It is hard to imagine that a Starbucks or McDonald’s suffering a similar fate would have experienced the same kind of community response.

Conclusion: Third Places and the Restoration of Community

As a commercial third place, Books and Company strengthens the social fabric of its regulars while the regulars support the business. The owner made a conscious decision to prioritize community building for its own sake in tandem with creating a business enterprise. As a small business owner, she was free to do that, whereas corporate fiduciary responsibilities require big businesses to prioritize profits. Instead, she makes business decisions with a view to making people feel like they belong. No sign indicates that the rest room is available only to customers. Space is available to organizations free of charge. Regulars feel comfortable staying all day, whether or not they regularly purchase coffee. Visitors regularly cuddle up for a good read without buying a book. The owner makes sure to have low priced items ($1-5) available so that everyone who wants to buy something can. She ensures that all of her employees are invested in getting to know the habitues. As a result, the regulars get to know each other too. This is truly a place where everyone knows your name.

Just as Books and Company is not the only place to get books and/ or coffee, neither is it the only provider of a “third place” sociability. Its personalization distinguishes it from businesses that primarily sell books and/or primarily sell coffee (e.g., Barnes & Noble, Starbucks) as well as from organizations that primarily provide physical space for sociability (e.g., community centers). Rather, it is representative of a type of business that binds its customers to itself through affect as well as merchandise. Thus, one might observe similar third place characteristics in other businesses where “regulars” gather.4

In the face of the retreating presence of traditional structures (such as churches), it is such third places that provide the base-level community foundation necessary to the growth of social capital. But it takes conscious effort to replace the atomizing instrumental relationships inherent in modern society. The explicit decision to prioritize affectual relationships and community building allows Books and Company to create a welcoming space that encourages visitors to build connections. Together, they cultivate an ecosystem where individuals thrive as members of a community. Because sometimes, you really do want to go where affectual relationships override the instrumental; where everybody knows your name.

Such micro-level communities begin within third places and nurture the interpersonal resources central to social capital. At a time when voluntary associations are on the decline, when society is polarized, and everyone feels alone, third places play an important role in maintaining civil society, encouraging community engagement, and ultimately supporting democracy.

Conflict of interest:

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

de Tocqueville, Alexis. [1835] 1945. Democracy in America. Trans. and ed. Phillips Bradley. New York: Vintage Books. View

Shapiro, Michael J. (2002). “Post-Liberal Civil Society and the Worlds of Neo-Tocquevillean Social Theory.” In Social Capital: Critical Perspectives on Community and ‘Bowling Alone, eds Scott L. McLean, David A. Schultz, and Manfred B. Steger. New York: New York University Press, 99-124. View

Schattschneider, E.E. (1960). Semi-Sovereign People. New York: Holt.View

Shapiro, Michael J. (1997). “Bowling Blind: Post Liberal Civil Society and the Worlds of New-Tocquevillean Social Theory.” Theory and Event, 1 (1). View

Young, Iris Marion. (1989). “Polity and Group Difference: A Critique of the Ideal of Universal Citizenship.” Ethics, 99 (January): 250-74. View

Cooper, Rachel. (2018). “What is Civil Society, Its Role and Value in 2018?” K4D Helpdesk Report. Brighton, UK: Institute of Development Studies. View

Putnam, Robert D. (2000). Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon and Schuster.View

Thompson, Derek. (2024a). “Why Americans Suddenly Stopped Hanging Out.” The Atlantic, 14 February. View

Thompson, Derek. (2022). “Why American Teens Are So Sad.” The Atlantic, 11 April. View

Office of the Surgeon General. (2023). Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community. View

Thompson, Derek. (2024b). “The True Cost of the Churchgoing Bust.” The Atlantic, 3 April. View

Jones, Jeffrey M. (2021). “U.S. Church Membership Falls Below Majority for the First Time.” Gallup. View

Smith, Gregory A., Patricia Tevington, Justin Nortey, Michael Rotolo, Asta Kallo, and Becka A. Alper. (2024). “Religious ‘Nones” in America: Who They Are and What They Believe.” Pew Research Center, 24 January. View

Oldenberg, Ray. (1989). The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Community Centers, Beauty Parlors, General Stores, Bars, Hangouts, and How they Get You Through the Day. New York: Paragon House. View

Voltaire. [1759] 1930. Candide. Williams, Belasco and Meyers. View

Post, Jerrold M. and Stephanie R Doucette. (2019). Dangerous Charisma: The Political Psychology of Donald Trump and His followers. Pegasus Books. View

Tönnies, Ferdinand. [1887] 2002. Community and Society: Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft. Trans. Charles P. Loomis. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications. View

Waters, Tony. (2014). “Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft Societies.” Entry prepared for the Encyclopedia of Sociology, 2nd Ed. (2015). View

Granovetter, Mark S. (1973). "The Strength of Weak Ties." American Journal of Sociology, 78 (6): 1360-80. View