Journal of Political Science and Public Opinion Volume 3 (2025), Article ID: JPSPO-120

https://doi.org/10.33790/jpspo1100120Research Article

Democratic Resilience or Autocratic Drift? Institutional Challenges in Bangladesh

Omme Habiba MA*, and Ross E. Burkhart

Department of Political Science, Boise State University, Boise, ID, United States.

Corresponding Author: Department of Political Science, Boise State University, Boise, ID, United States.

Received date: 22nd April, 2025

Accepted date: 24th May, 2025

Published date: 26th May, 2025

Citation: Habiba, O., & Burkhart, R. E., (2025). Democratic Resilience or Autocratic Drift? Institutional Challenges in Bangladesh. J Poli Sci Publi Opin, 3(1): 120.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Abstract

Bangladesh stands at a critical juncture where the competing forces of democratic resilience and autocratic drift define its political landscape. Despite impressive economic growth and improved human development indicators, Bangladesh has witnessed a steady erosion of its democratic institutions. While modernization theory suggests that economic development fosters democracy, the country's political trajectory challenges this assumption. The persistence of executive dominance, electoral manipulation, and a lack of judicial independence indicates that institutional strength, rather than economic prosperity, is the decisive factor in democratization.

This paper argues that economic indicators alone do not determine democratic consolidation. Instead, an independent judiciary, electoral integrity, and a politically neutral military play a far more significant role in preserving democratic governance. The study integrates a mixed-methods approach, combining quantitative data from Freedom House, the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Index, and World Bank economic reports with qualitative analyses of Bangladesh's electoral history, judicial reforms, and civil-military relations. The findings underscore the necessity for judicial reforms, electoral accountability, and military oversight to prevent Bangladesh from sliding further into authoritarian governance.

Keywords: Governance, Political Institutions, Executive Dominance, Electoral Legitimacy, Civil Liberties, Judicial Independence, Political Polarization, RegimeTrajectory.

Introduction

Since gaining independence from Pakistan in 1971 [1], Bangladesh has oscillated between democratic openings and authoritarian rule [2]. The nation’s founding was deeply rooted in the ideals of popular sovereignty and parliamentary governance [3], yet the initial years saw a rapid centralization of power. The assassination of the country’s first president, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, in 1975 [4], led to a period of military rule that lasted until 1991. The return to civilian rule through multiparty elections in the 1990s was initially seen as a step toward democratic consolidation [5], yet the promise of democratic stability remained elusive [6]. The past two decades have witnessed an incremental erosion of democratic institutions [7], as political competition has given way to executive dominance, electoral manipulation, and a lack of judicial independence [8].

While economic progress has been a hallmark of Bangladesh’s development trajectory [9], its democratic institutions have struggled to keep pace [1]. Unlike many other countries that transitioned toward democracy as they developed [10], Bangladesh’s political landscape remains dominated by weak institutional frameworks and contested governance structures [11]. The growing authoritarian tendencies of its ruling elite [12], coupled with the diminishing role of independent institutions, raise fundamental questions about the country's ability to sustain democratic governance [13].

This paper seeks to answer whether Bangladesh’s democratization follows the predictions of modernization theory or if institutional factors play a more decisive role in shaping political outcomes. By engaging with both theoretical debates and empirical evidence, this study argues that economic growth alone is insufficient to sustain democracy. Instead, the erosion of judicial independence, the manipulation of electoral processes [10], and the increasing role of security forces in governance have created conditions that favor autocratic drift.

Materials and Methods

This research employs a mixed-methods approach, integrating both quantitative and qualitative data to examine democratic resilience in Bangladesh.

Quantitative data sources include V-Dem electoral democracy indices from 1971-2023, Freedom House democracy scores from 1972-2023, POLITY democracy scores from 1971-2018, and World Bank economic indicators, including GDP per capita from 1971 2023, Human Development Index (HDI) scores from 1990-2023, and Gini coefficients signifying income inequality from 1971-2023. These data help establish a correlation between economic growth and political freedom, allowing for a comparative analysis with other countries facing similar democratic challenges.

Qualitative analyses focus on key political events in Bangladesh’s democratic trajectory, including the controversial elections of 2014 and 2018, the judicial crisis surrounding the removal of Chief Justice Surendra Kumar Sinha in 2017, and the role of security forces in governance.

This study relies on publicly available data, government reports, and academic literature. No human or animal subjects were involved, ensuring compliance with ethical research standards.

Modernization Theory and Bangladesh

The relationship between economic development and democracy has been a central debate in political science [14]. Seymour Martin Lipset’s modernization theory posits that higher levels of economic development led to democratic stability [15], arguing that wealthier societies are better positioned to sustain democratic governance due to factors such as literacy, urbanization, and the emergence of a middle class [16]. This theory posits that higher levels of economic development—measured through income, education, and urbanization—create conditions conducive to democracy. Following Lipset, scholars such as Carles Boix and Daron Acemoglu have explored the linkages between GDPs per capita and the likelihood of democratic transition [17], suggesting that economic development reduces political volatility and incentivizes democratic accountability [18].

In contrast, Michael Ross’s research on authoritarian resilience in resource-rich economies challenges the deterministic assumptions of modernization theory [19]. Ross argues that while economic growth can foster democratic transitions in some cases [20], it can also entrench authoritarian rule if political elites use economic resources to consolidate power [21]. Bangladesh’s experience aligns with Ross’s argument, as economic growth has not translated into a proportional strengthening of democratic institutions [22]. Economic development, they note, can be captured by elites to consolidate authoritarian control, especially when state institutions are weak or co-opted.

In this context, Bangladesh provides a critical case. It has witnessed sustained economic growth (average annual GDP growth over 6% since 2010) and improvements in HDI, yet its democratic institutions have eroded. This study revisits the theory-practice linkage through empirical analysis and institutional diagnostics.

Regression-based studies examining global patterns of democratization have often relied on cross-country comparisons using metrics such as GDP per capita, HDI rankings, and democracy indices. Ferral’s work on institutional models of democracy suggests that economic prosperity alone does not drive democratic outcomes [23]; rather, governance structures and institutional frameworks play a mediating role [24].

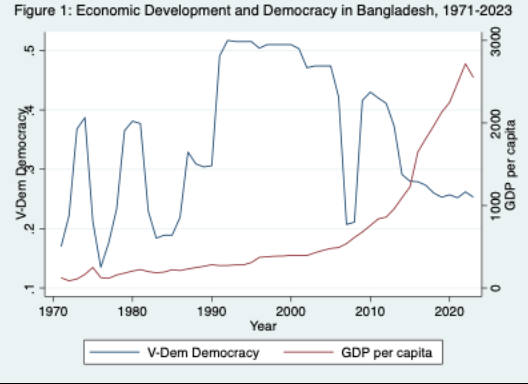

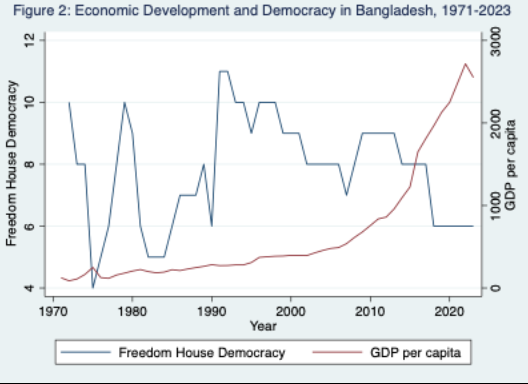

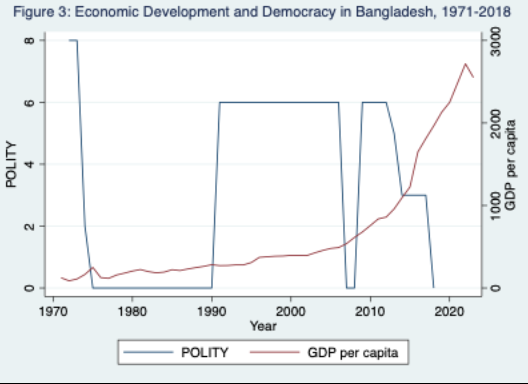

Studies using democracy data from V-Dem, POLITY, and Freedom House suggest that while there is a broad correlation between economic development and democratization, exceptions like Bangladesh illustrate the limitations of a purely economic model of democracy. We directly show the contrary case of Bangladesh using the graphs below, clearly showing the climbdown from democracy’s heights during the past two decades and the rise in economic development and human development during that time frame1.

Bangladesh’s case complicates the traditional modernization narrative [13]. While its GDP per capita and HDI scores have improved over the years, its democracy scores have declined [26]. The country’s political landscape, characterized by executive dominance, weak judicial independence, and a compromised electoral system [27], suggests that economic progress has not necessarily translated into democratic deepening [28]. Instead, the persistence of institutional weaknesses and governance deficits indicates that other factors—beyond economic growth—are shaping the country’s political trajectory [29].

Quantitative Modeling of Modernization Theory in Bangladesh

To assess whether modernization theory explains Bangladesh’s democratic trajectory, this study conducts regression analyses using GDP per capita, HDI, and income inequality (Gini coefficient) as predictors of democratic quality. These variables are commonly used in this literature [18,30-34].

As a prelude to these analyses, we first present descriptive statistics of the measured variables.

Examining the mean and the range of values for each democracy variable, the general conclusion is that Bangladesh scores lower than the global mean value across these measures. Regarding development, the GDP/capita scores for Bangladesh at their highest are generally low to middle income. The HDI scores at their highest are in the medium range for Bangladesh, but are generally low. The Gini coefficients generally indicate lower income inequality levels for Bangladesh than the global average.

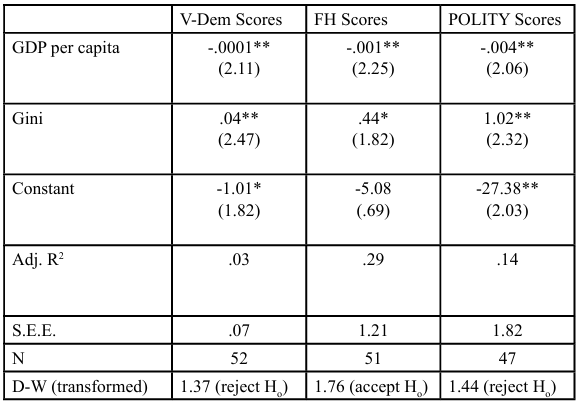

Tables 2 and 3 presents results from models using V-Dem, POLITY, and Freedom House scores from 1971 to 2023. Interestingly, GDP and HDI show negative associations with democracy, while inequality often correlates positively. These findings challenge the core assumption of modernization theory and suggest that Bangladesh’s democratic outcomes may be shaped more by institutional or political factors than by development alone.

Where figures in parentheses are absolute t-ratios, ** indicates statistical significance at the .05 level, two-tailed test, * indicates statistical significance at the .10 level, two-tailed test, Adj. R2 is the adjusted R-squared statistic, S.E.E. is the standard error of estimate, N is the number of cases, D-W (transformed) is the Durbin-Watson statistic transformed by the iterative procedure in the Prais-Winsten AR(1) regression estimation.

(The dataset consists of annual observations in Bangladesh from 1971-2023, though Freedom House democracy data are only available from 1972-2023, and POLITY democracy data are only available from 1971-2018.)

Where figures in parentheses are absolute t-ratios, ** indicates statistical significance at the .05 level, two-tailed test, * indicates statistical significance at the .10 level, two-tailed test, Adj. R2 is the adjusted R-squared statistic, S.E.E. is the standard error of estimate, N is the number of cases, D-W (transformed) is the Durbin-Watson statistic transformed by the iterative procedure in the Prais-Winsten AR(1) regression estimation.

(The dataset consists of annual observations in Bangladesh from 1971-2023, though Freedom House democracy data are only available from 1972-2023, POLITY [36] democracy data are only available from 1971-2018, and HDI scores are only available from 1990-2023.)

In each estimation, the modernization variables, both GDP/capita and HDI, are signed negative and statistically significant at the .05 level, controlling for the GINI coefficient of income inequality. After correcting for autocorrelation, as modernization increases in Bangladesh, democracy scores decrease, no matter if democracy is measured by V-Dem, Freedom House, or POLITY or if modernization is measured with GDP/capita or HDI2.

The results indicate that modernization theory is not confirmed as an explainer of democratization in Bangladesh. Controlling for income inequality, as GDP per capita and HDI increase, democracy scores across the board decrease, whether V-Dem, POLITY, or Freedom House measure democracy. This is the opposite of what the theory predicts, which is that greater wealth and development lead to more democratic performance, not less. We must look to other theories to explain democratization patterns in Bangladesh.

The Qualitative Case For Bangladesh

Beyond economic indicators, the governance structures and institutional dynamics of Bangladesh provide a more compelling explanation for its democratic erosion [37]. While modernization theory suggests that development fosters democratic norms [38], Bangladesh’s experience shows that institutional design and political incentives are more decisive in shaping democratic resilience [39].

The country’s judicial system has been systematically weakened by executive interference, limiting its ability to function as an independent arbiter of political disputes [40]. The forced resignation of Chief Justice Surendra Kumar Sinha in 2017 exemplifies how the judiciary has been subordinated to political interests [41]. Similarly, the passage of the Digital Security Act (DSA) in 2018 has curtailed fundamental freedoms, demonstrating how legal frameworks can be weaponized to suppress dissent [42].

Electoral integrity remains another critical challenge [43]. While elections are formally held at regular intervals, the credibility of the electoral process has been undermined by systematic fraud, voter suppression, and opposition marginalization [44]. The 2014 general election, boycotted by the main opposition, resulted in an uncompetitive political landscape [45], while the 2018 elections were marked by widespread allegations of ballot-stuffing and coercion. The role of the Election Commission, ostensibly an independent body, has been called into question due to its perceived bias in favor of the ruling party [46].

Civil-military relations also play a crucial role in shaping Bangladesh’s governance structure [47]. While the country has avoided direct military rule since 1991, security forces continue to exert significant influence over political affairs [48]. The military backed caretaker government of 2007–2008 demonstrated that the security establishment remains a key political actor [49]. Additionally, the Rapid Action Battalion (RAB), an elite paramilitary force, has been implicated in extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances, highlighting the securitization of governance [50]. The imposition of U.S. sanctions on RAB officials in 2021 underscores the international concerns over the militarization of law enforcement [51].

Taken together, these factors illustrate that Bangladesh’s democratic challenges stem not from economic limitations but from governance deficits [52]. The erosion of judicial independence, electoral credibility, and civilian oversight over security forces suggests that institutional decay [53], rather than economic underdevelopment, is the primary driver of democratic backsliding.

Qualitative Results

Judicial Independence and Executive Overreach

The judiciary in Bangladesh has been significantly weakened by executive interference, which has compromised its ability to function as an independent check on government power [54]. A striking example of this was the removal of Chief Justice Surendra Kumar Sinha in 2017 [55]. Sinha presided over the Supreme Court's ruling that struck down the 16th Amendment to the Constitution, which granted Parliament the power to remove judges [56]. This decision was widely seen as a step toward judicial independence, yet soon after, Sinha was forced to resign and flee the country, citing political persecution. His removal sent a clear message that judicial decisions unfavorable to the government would not be tolerated.

The passage of the Digital Security Act (DSA) in 2018 further demonstrates the judiciary’s failure to protect fundamental rights [57]. The law has been used to prosecute over 2,000 journalists, activists, and opposition figures for alleged anti-state activities [58]. Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have criticized the legislation for being overly broad and for criminalizing dissent [59], yet the courts have largely upheld their provisions, demonstrating a lack of judicial independence [60].

Electoral Integrity and Political Manipulation

Bangladesh’s electoral process has been repeatedly undermined by fraud, voter suppression, and government control over election oversight [61]. The 2014 general election was boycotted by the opposition Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), leading to a one party parliamentary victory for the ruling Awami League [62]. The 2018 elections were marred by allegations of ballot-stuffing, intimidation of opposition candidates, and a lack of transparency in vote counting [63]. Transparency International reported widespread irregularities, while the European Union and the United Nations expressed concerns about the integrity of the electoral process [64].

Civil-Military Relations and Democratic Stability

Although Bangladesh has avoided direct military rule since 1991, the armed forces continue to exert influence over political affairs [65]. The 2007-2008 military-backed caretaker government demonstrated that the security establishment remains a key player in governance [66]. Additionally, the Rapid Action Battalion (RAB), an elite paramilitary force, has been accused of extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances. In 2021, the U.S. government-imposed sanctions on RAB officials for human rights violations, further highlighting the militarization of law enforcement [67].

Discussion and Conclusion

This study challenges modernization theory by demonstrating that economic growth alone does not guarantee democratization. Bangladesh’s experience underscores the importance of institutional resilience in sustaining democracy. Without judicial independence, free and fair elections, and civilian control over the military, economic prosperity cannot prevent democratic erosion.

Bangladesh’s political trajectory increasingly resembles Pakistan’s hybrid democracy, where electoral processes exist but are heavily manipulated, and civilian governance remains subordinate to security forces. Without urgent reforms to restore judicial independence, ensure electoral transparency, and curb executive overreach, Bangladesh risks further democratic decline.

The findings of this study suggest that strengthening institutional safeguards is the only viable path toward democratic consolidation. The next decade will be critical in determining whether Bangladesh fortifies its democratic institutions or continues its slide into authoritarian governance.

Conflict of interest:

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Datta, S. (2003). Bangladesh’s political evolution: Growing uncertainties. Strategic Analysis, 27(2), 233–249. View

Ahmed, N. (2002). The Parliament of Bangladesh. United Kingdom. Ashgate. View

Obaidullah, A. T. M. (2018). Institutionalization of the parliament in Bangladesh: A study of donor intervention for reorganization and development. Institutionalization of the Parliament in Bangladesh: A Study of Donor Intervention for Reorganization and Development, 1–338. View

Van Schendel, W. (2020). History of Bangladesh. Cambridge University Press. View

Naziz, A. (2020). Sustainable development goals and media framing: an analysis of road safety governance in Bangladeshi newspapers. Policy Sciences, 53(4), 759–777. View

Beachler, D. (2007). The politics of genocide scholarship: the case of Bangladesh. Patterns of Prejudice, 41(5), 467–492. View

Chowdhury, N. S. (2025). The Return of Politics in Bangladesh. Journal of Democracy, 36(1), 65–78. View

S.M. Ruhul Amin, Dr. D. K. G. (2024). A DECISIVE INTERVENTION INDIA’S MILITARY ROLE IN THE BANGLADESH LIBERATION WAR. International Journal of Innovation Studies, 8(1), 567–577. View

Bird, J., Li, Y., Rahman, H. Zillur., Rama, M., & Venables, A. (2018). Toward great Dhaka : a new urban development paradigm eastward. World Bank Publication, 160. View

Luís, C. (2021). Free and Fair Elections to Electoral Integrity: Trends, Challenges, and Populism. 271–283. View

Shirah, R. (2015). Electoral authoritarianism and political unrest. 37(4), 470–484. View

Olarinde, M. O., Abiona, A. A., & Ajinaja, M. O. (2024). Electoral System Optimization Through Voting Quorum, Voter Turnout, Candidate Viability, and Electoral Integrity Analysis. Asian Journal of Electrical Sciences, 13(2), 25–35. View

Siddiquee, N. A. (1999). Bureaucratic accountability in Bangladesh: Challenges and limitations. Asian Journal of Political Science, 7(2), 88–104. View

Robinson, J. A. (2006). Economic development and democracy. Annual Review of Political Science, 9(Volume 9, 2006), 503–527. View

Lipset, S. M. (1959). Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy1. American Political Science Review, 53(1), 69–105. View

Leftwich, A. (1993). Governance, democracy and development in the Third World. Third World Quarterly, 14(3), 605–624. View

Boix, C., Miller, M., & Rosato, S. (2013). A Complete Data Set of Political Regimes, 1800-2007. Comparative Political Studies, 46(12), 1523–1554. View

Acemoglu, D., Naidu, S., Restrepo, P., & Robinson, J. A. (2019). Democracy does cause growth. Journal of Political Economy, 127(1), 47–100. View

Ross, M. L. (2015). What have we learned about the resource curse? Annual Review of Political Science, 18(Volume 18, 2015), 239–259. View

Ross, M. L. (2000). Does Resource Wealth Cause Authoritarian Rule? In Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, August. View

Lipset, S. M. (1959). Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy1. American Political Science Review, 53(1), 69–105. View

Hess, S. (2013). From the Arab Spring to the Chinese Winter: The institutional sources of authoritarian vulnerability and resilience in Egypt, Tunisia, and China. International Political Science Review, 34(3), 254–272. View

Carugati, F. (2020). Democratic Stability: A Long View. Annual Review of Political Science (Palo Alto, Calif. Print), 23, 59–75. View

Fu, Q., Stephenson, M., & Ebrahim, A. (2004). Trust, Social Capital and Organizational Effectiveness. Virginia Tech. View

Coppedge, M., J. Gerring, A. Glynn, C. H. Knutsen, S. I. Lindberg, D. Pemstein, B. Seim, S.-E. Skaaning, and J. Teorell. (2022). Varieties of Democracy: Measuring Two Centuries of Political Change. New York: Cambridge University Press. View

Liotti, G., MUSELLA, M., & D’ISANTO, F. (2018). Does democracy improve human development? Evidence from former socialist countries. Eastern Journal of European Studies, 9(2), 69–88.View

Hossain Mollah, A. (2012). Independence of judiciary in Bangladesh: An overview. International Journal of Law and Management, 54(1), 61–77. View

Jahan, R. (2015). The Parliament of Bangladesh: Representation and Accountability. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 21(2), 250–269. View

Mozahidul Islam, M. (2015). Electoral violence in Bangladesh: Does a confrontational bipolar political system matter? Commonwealth & Comparative Politics, 53(4), 359–380. View

Burkhart, R. E., and Lewis-Beck, M.S. (1994). Comparative Democracy: The Economic Development Thesis.” American Political Science Review 88:903-10. View

Burkhart, R.E. (1997). Comparative Democracy and Income Distribution: Shape and Direction of the Causal Arrow. The Journal of Politics 59:148-64. View

Przeworski, A., & Limongi, F. (1997). Modernization: Theories and Facts. World Politics 49:155-83. View

Gerring, J., Bond, P., Barndt, W. T., and Moreno, C. (2005). Democracy and Economic Growth: A Historical Perspective. World Politics 57:323-64. View

Boix, C. (2011). Democracy, Development, and the International System. American Political Science Review 105:809-28. View

Coppedge, M., J. Gerring, A. Glynn, C. H. Knutsen, S. I. Lindberg, D. Pemstein, B. Seim, S.-E. Skaaning, and J. Teorell. (2022). Varieties of Democracy: Measuring Two Centuries of Political Change. New York: Cambridge University Press. View

POLITY Project. (2025). View

Panday, P. K. (2023). Deficits in Democratic Governance in Developing Countries: The Bangladesh Scenario. Journal of Asian and African Studies. View

Kailash, K. K. (2013). The Emerging Politics of Cohabitation: New Challenges. Emerging Trends in Indian Politics: The Fifteenth General Election, 86–113. View

Lewis, D. (2017). Organising and Representing the Poor in a Clientelistic Democracy: the Decline of Radical NGOs in Bangladesh. The Journal of Development Studies, 53(10), 1545–1567. View

Hussain, M. L. (2023). Constituting limits and accountability of the executive power in Bangladesh. A History of the Constitution of Bangladesh: The Founding, Development, and Way Ahead, 129–144. View

Helmich, M. (2022). Using Law to Depoliticize Adjudication?: A Skeptical Thesis. View

Marjan, S. M. H. (2024). Addressing Cyber Deviance in Hybrid Political Systems. The Routledge International Handbook of Online Deviance, 721–736. View

Norris, P. (2022). Challenges in electoral integrity. Routledge Handbook of Election Law, 87–100. View

Panday, P. K. (2023). Deficits in Democratic Governance in Developing Countries: The Bangladesh Scenario. Journal of Asian and African Studies. View

Niaz, N. (2025). Deterioration of Electoral Democracy in Bangladesh and Turkey since the 2010s: Comparative Study of Bangladesh Awami League (BAL) & Justice and Development Party (AKP). View

Akhter, M. Y. (2017). Electoral Corruption in Bangladesh. Electoral Corruption in Bangladesh, 1–294. View

Wolf, S. O. (2013). Civil-Military Relations and Democracy in Bangladesh. SSRN Electronic Journal. View

Siddiqui, K., Ahmed, J., Siddique, K., Huq, S., Hossain, A., Nazimud-Doula, S., & Rezawana, N. (2016). Social Formation in Dhaka, 1985-2005: A Longitudinal Study of Society in a Third World Megacity. Social Formation in Dhaka, 1985-2005: A Longitudinal Study of Society in a Third World Megacity, 1–406. View

Ahamed, A., Rahman, Md. S., & Hossain, N. (2020). Evolution of Civil-Military Relations in Bangladesh: A Comparative Study in the Context of Developing Countries. Technium Social Sciences Journal, 10. View

Karim, M. A. (2019). Political Culture and Institution-Building Impacting Civil–Military Relations (CMR) in Bangladesh, Guns & Roses: Comparative Civil-Military Relations in the Changing Security Environment, 75–96. View

Faroque, S. (2024). Policing green crime in Bangladesh: challenges for law enforcement, environmental agencies and society.View

Reza, S. M. A., Bhuiyan, U., & Mazhar, M. (2025). Analyzing the Role of Key Stakeholders in the July Uprising 2024 in Bangladesh: Actors and Factors Approach. Journal of Political Science, 25, 214–237. View

Siddik, A. B. (2024). Bangladesh’s July Revolution: Analyzing the 2024 Movement for Free Speech and Democracy. View

Jackman, D. (2021). Students, movements, and the threat to authoritarianism in Bangladesh. Contemporary South Asia, 29(2), 181–197. View

Bari, M. E. (2020). The Recent Changes Introduced to the Method of Removal of Judges of the Supreme Court of Bangladesh & the Consequent Triumph of an All-Powerful Executive over the Judiciary: Judicial Independence in Peril. Cardozo International & Comparative Law Review, 4. View

Ghosh, S. C. (2023). Conceptualizing student movements in Bangladesh post-2013: a qualitative and comparative case study of the Quota Reform Movement and the Road Safety Movement. Social Identities, 29(6), 534–554. View

Biswas, B. D. R. Md. M. (2018). Major Challenges of Public Administration in Bangladesh: Few Observations and Suggestions. View

Solaiman, S. M. (2022). Corruption and Judges’ Personal Independence in the Judiciary of Bangladesh: One Bad Apple Can Spoil the Bunch. Cardozo International & Comparative Law Review, 6. View

Hasan, S. (2024). Constitutionalism in Muslim Majority Countries: A Review of the Experiences and Lessons. View

Herbert, S. (2019). Conflict Analysis of Bangladesh. View

Chowdhury, M. S. A. (2024). Challenges to media freedom in election reporting in Bangladesh. View

Chowdhury, M. J. A. (2023b). Parliament of Bangladesh: Constitutional position and contributions. A History of the Constitution of Bangladesh: The Founding, Development, and Way Ahead, 145–160. View

Chowdhury, M. J. A. (2023a). Fifty Years of Electioneering in Bangladesh: The Collapse of a Constitutional Design. In The Constitutional Law of Bangladesh: Progression and Transformation at its 50th Anniversary. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore, 173–193. View

Bangladesh: Contemporary Political History. (2023). Handbook of South Asia: Political Development, 153–178. View

Subedi, D. B., Brasted, H., Strokirch, K. von, & Scott, A. (2024). The Routledge handbook of populism in the Asia Pacific. 425. View

Dos Santos, A. N. (2007). MILITARY INTERVENTION AND SECESSION IN SOUTH ASIA: The Cases of Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Kashmir, and Punjab. Military Intervention and Secession in South Asia: The Cases of Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Kashmir, and Punjab, 1–201. View

Pattanaik, S. S. (2005). Internal Political Dynamics and Bangladesh’s Foreign Policy Towards India. Strategic Analysis, 29(3), 395–426. View