Journal of Political Science and Public Opinion Volume 3 (2025), Article ID: JPSPO-121

https://doi.org/10.33790/jpspo1100121Research Article

The Relationship Between Conflict Avoidance and Support for Speech Restrictions

Mark Ramirez

Professor, School of Politics and Global Studies, Arizona State University, P.O. Box 873902, Tempe, AZ 85287-3902, United States.

Corresponding Author: Mark Ramirez, Professor, School of Politics and Global Studies, Arizona State University, P.O. Box 873902, Tempe, AZ 85287-3902, United States.

Received date: 21st February, 2025

Accepted date: 24th May, 2025

Published date: 26th May, 2025

Citation: Ramirez, M., (2025). The Relationship Between Conflict Avoidance and Support for Speech Restrictions. J Poli Sci Publi Opin, 3(1): 121.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Abstract

Mass publics often express a desire for public and private institutions to place restrictions on speech. This research proposes a personality-based explanation of support for such censorship focusing on the trait of conflict avoidance. For people who seek to avoid conflict, restrictions on speech serve as a mechanism to reduce social disagreements when speech is conflict-laden. I test this theory using a national survey of U.S. adults. OLS regression estimates show conflict avoidance relates to greater calls for public and private institutions to restrict controversial speech. Moreover, conflict avoidance increases people’s susceptibility to censorship related counterarguments. When informed about the effectiveness of banning certain types of speech, free speech advocates who wish to avoid conflict exhibit greater attitude change towards censorship than those who embrace conflict. When informed that censorship is unlikely to reduce conflict, people who wish to avoid conflict can become more supportive of free speech.

Keywords: Personality, Expression, Censorship, Political Tolerance, Attitude Change, Public Opinion

Introduction

Free speech is a hallmark of U.S. democracy. Citizens routinely proclaim the First Amendment as a centerpiece of U.S. government. A 2021 Knight Foundation poll reports 68% of Americans “strongly agree” and another 23% “mildly agree” that “free speech is an important part of American democracy.”1 A 2019 Pew study found 96% of U.S. adults believe being able to say what you want without government censorship is “very” or “somewhat” important to them2. The almost unanimous support for free speech, in the abstract, mirrors some of the earliest public opinion polling on the subject [1].

Yet, many citizens also express support for censorship. Censorship is defined here as the suppression of speech, public communication, or other information. The Knight Foundation poll found that only 42% of Americans agree with a recent Supreme Court ruling to protect certain forms of offensive speech3. People are also expressing support for private companies to censor speech deemed objectionable, offensive, or dangerous. A mere 29% of Americans state they oppose censorship by privately-owned social media companies with citizen reporting or flagging of other people’s speech a key form of speech regulation on social media [2].

This indicates discussions have grown beyond concerns about government authorities restricting speech and into how private companies and citizens engage in censorship. Thus, there is a need to understand the degree people tolerate different types of speech [3] and whether the sources of tolerating different kinds of speech are similar across public and private institutions. The First Amendment applies only to government institutions leaving private enterprises free to regulate content as they see fit. Of course, citizen conceptualizations of free speech can extend far beyond what constitutional framers, legislative bodies, and courts have guaranteed. Recent discussions of public “canceling” and demands to place limits on speech enforcement by private enterprises (i.e., social media companies, the National Football League) suggest that many people erroneously believe free speech rights extend to private institutions or desire to extend such rights to these institutions.

Empirical analyses of public support of different kinds of speech have focused on government censorship and fallen under broader examinations of political toleration. The focus of these studies has been on the role of learned beliefs (i.e., education, cultural values, norms, and perceptions of threat) in altering support for a range of civil liberties that include free speech [4,5,6]. For instance, people are less tolerant of supporting civil liberties for groups they dislike when they feel threated by the group [7,8]. People that are less inclined to endorse democratic norms and values are also less willing to be tolerant of speech from groups they dislike [9,10]. Yet, how to use these beliefs in a manner that promotes further toleration has been elusive thereby pushing scholars to seek new factors that shape tolerance judgments [11].

A few studies have examined the role of personality traits in increasing support for free speech. Marcus et al. [5] combines measures of dogmatism and trust into a composite “psychological insecurity” variable. Although the idea that those who are psychologically insecure are more likely to restrict speech was promising, adequate tests of the theory have been elusive. Factors such as dogmatism and social trust are typically used as measures of psychological insecurity despite having an unclear relationship to the concept. Moreover, such factors might be more representative of learned cultural beliefs rather than an inherent personality trait suggesting we still don’t know whether these personality traits relate to toleration [12]. Harell, Hinckley, and Mansell [13] provide an exception showing that empathic people are more likely to reject various forms of hate speech. This latter research shows the potential fertility of examining personality traits in this domain.

The purpose of this research is to 1) examine a personality-based explanation of who tolerates divisive speech and 2) describe the extent such beliefs have undergone a conflict extension---shifting beyond government restrictions of speech and into both public and private restrictions on various types of speech. Specifically, it argues that conflict avoidance should relate to both people’s toleration of various types of speech and their willingness to conceded to censorship related counterarguments. For people who seek to avoid conflict, speech prohibition serves as a mechanism to reduce social or psychological conflict when speech is controversial. People with little appetite for conflict should also be more willing to back down in the name of civility when confronted with a censorship-related counterargument. Finally, these relationships should hold for beliefs about the toleration of divisive speech across both public and private institutions as minimizing disagreement is an overriding goal for conflict avoidant personality types irrespective of context. Thus, the need to reduce conflict provides an explanation of why people are less tolerant of different types of speech in both the public and private sphere.

These arguments are tested using a large, national survey. Rather than regulating personality to an intervening role [5], the study provides a direct test of the relationship between conflict avoidance and support for speech regulations. The results show that people who prefer to avoid conflict are more likely to support the censorship of divisive speech by the government and private social media companies. Moreover, conflict avoidance is shown to be a viable moderator of persuasive counterarguments within this context. Thus, the findings extend our knowledge of why some people oppose the toleration of divisive speech as well as highlights a mechanism to understand attitude change.

Conflict Avoidance

Conflict avoidance is a personality trait where a person tends to remove themselves from unpleasant situations, and in particular, discussions that involve disagreement. It is one-half of a dual motivational system consisting of avoidance of threat (avoidance motivation) and reward seeking (approach motivation) [14]. This approach-avoidant motivational system is found in organisms across evolutionary history [15] helping them adapt to their environment by pulling them toward beneficial, and away from potentially harmful, outcomes [16]. People’s approach and avoidant reactions are often automatic and unconscious [17] although they can also represent more instrumental cognitive and goal-oriented processes [18].

Individual differences in approach-avoidant temperaments are both heritable and learned. There is a broad network of neurophysiological mechanisms (e.g., brain stem, cortex, spinal cord; hormonal activity) that shape individual approach-avoid temperaments [19]. Approach avoidant temperaments also develop as a coping strategy from childhood socialization and trauma [20]. They remain relatively stable across a person’s lifespan and harden through maturation [21,22].

Approach and avoidant temperaments produce automatic affective, cognitive, and behavioral responses to both real and imagined stimuli and help create consistency in people’s thoughts and behaviors across a wide range of contexts [10,23]. People who are conflict avoidant---defined as a general neurobiological sensitivity to disagreement---engage in a wide range of coping strategies in order to reduce stress, dissonance, and other forms of discomfort. People with a conflict avoidant temperament often tell jokes during a contentious conversation or situation, change the subject of conversation away from unpleasant or controversial subjects, table the discussion for a later date, avoid disagreement with other people through false affirmation, or simply refuse to engage in a discussion [24].

Conflict avoidant strategies align with the regulation of conversations. A person with a conflict avoidant temperament is motivated to reduce their own stress that arises when encountering conflict. Eliminating the topic from conversation might be seen as a solution to minimizing a conflict. For non-conflict avoidant people, debate and conflict might serve some larger goal such as providing information or winnowing out weak arguments. Conflict avoidant people are more likely to let such goals go unfulfilled in order to satisfy their desire to minimize conflict---an objective at the top of their personal goal hierarchy [25]. Avoidant personality types have also been shown to view discussion of conflictual topics as “futile” believing that debate and deliberation rarely bring resolution to a conflict [25]. Since debate creates stress and discomfort for an avoidant personality, and no clear benefit in resolving a conflict, avoidant personalities should be more accepting of censoring the conflict. Censorship might also provide a sense of control for conflict avoidant personalities over their environment [26]. This leads to the following expectation,

H1: Conflict avoidance should increase the desire to censor divisive speech.

Conflict Avoidance and Attitude Change

Conflict avoidance is also likely to moderate an important aspect of expressions of support for censorship---its malleability. Some scholars have depicted survey responses as an initial response or a starting position [27]. When provided with a counterargument, some people are willing to update their opinions from this starting position. In this framework, survey responses do not represent a fixed attitude, but a sampling of potential acceptable responses [28]. The counterargument introduces a new pool of potentially acceptable considerations that the respondent can either reject or accept. Accepted counterarguments are then integrated into an updated opinion.

In such situations, counterarguments highlight conflict between the person’s initial attitude and the new information. A person who does not mind conflict should have less difficulty sticking with their original response and, in some cases, might dig into their initial position hardening their attitude, i.e., the common backlash effect to persuasive arguments [29]. A conflict avoidant personality type, in contrast, should be more likely to choose the easiest path to minimize conflict. In the case of a counterargument, this might be to shift their position in the direction of the counterargument. Shifting a position toward the counterargument minimizes the discrepancy between the initial attitude and the new information. This leads to the following expectation,

H2: Counterarguments should have a greater effect on conflict avoidant personality types.

Given that conflict avoidant personality types are more likely to desire restrictions on conflictual speech, it also seems possible that such people would be more responsive to counterarguments in favor of speech restrictions than counterarguments opposed to the expansion of conflictual speech. Thus, a conflict avoidant person receiving a pro-censorship argument is expected to move their opinion in the direction of the counterargument (as a means to avoid immediate conflict within the interview context) and be more receptive to the argument itself (censoring future conflictual political speech). This leads to the following expectation,

H3: The effect of conflict avoidance on attitude change should be greater when arguments are in favor of censorship relative to arguments opposed to censorship.

Methodology

These hypotheses are tested using a sample of 1,000 US adults from the 2020 Cooperative Election Study (CES). The CES is a two-wave pre and post-election panel study administered by YouGov. YouGov uses the U.S. Census American Community Survey to generate a target population representative of all U.S. adults. A random sample is drawn from the target population selected by stratification by gender, race, age, education, and voter registration along with simple random sampling within strata [30].

In the pre-election wave of the survey, respondents were asked about their orientations toward conflict. Two questions ask about conflict avoidant orientations (feeling uneasy in when people argue and comfort in expressing beliefs during an argument) and two questions about conflict approach orientations (enjoy disagreement and actively seek out conflict). These questions explicitly omit references to political conflict due to the desire to measure non political conflict avoidant temperaments that should apply across a range of political and non-political contexts. An exploratory factor analyses shows responses to the four questions load on a dominant latent factor (Eigenvalue=1.79) with individual factor loadings ranging from .45 to .78. Responses on the variable range from 5 (high conflict avoidance) to 1 (the absence of conflict avoidance).

An initial measure of support for speech regulations derives from a pre-election wave question asking respondents if they approve of “hate speech” rules by “public colleges and universities” that prohibits “speech that offends or threatens.” Responses to this “hate speech” question range on a five-point scale from “strongly approve” to “strongly disapprove.” Public colleges and universities are state institutions and have implemented various speech codes under the Supreme Court’s “compelling interest” for educational purposes argument in United States v. O’Brien (1968). Subsequent court rulings have ruled against such speech codes (e.g., Doe v. University of Michigan) creating a controversial and potentially grey area in free speech rights.

A second measure of support for speech restrictions uses the least-liked measures of political toleration [31]. The pre-election survey asks respondents to select their least-liked group from a list of both right-leaning and left-leaning groups. The selected group is then inserted into two questions on the post-election survey asking the respondent how much they agree or disagree with, “the government should guarantee that [least-liked group) be allowed to give a speech in your community” and “the government should guarantee that [least-liked group] be allowed to speak at any college or university.” Responses range on a five-point scale from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.” An exploratory factor analysis shows single latent factor (Eigenvalue = 1.88) with factor loadings for both questions equal to .97. These items are combined into an additive government “least-liked” censorship index.

Support for speech restrictions by private sector companies is measured from six questions asking respondents if social media companies should remove certain types of speech: “false information about election processes,” “sexual harassment speech,” “hate speech toward racial minorities,” “hate symbols and racist images,” “speech that directly incites violence,” “false information about COVID-19.” Responses range on a five-point scale from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.” An exploratory factor analysis shows responses load on a single factor (Eigenvalue=5.32) with factor loadings ranging from .91 to .96. These questions are combined in an additive “social media” censorship index.

The pre-election wave of the survey contained various measures of concepts described in previous studies as correlated with support for either free speech directly or political intolerance more broadly. People are generally more willing to restrict free speech when they feel threatened by out-groups, hold ethnocentric or prejudicial beliefs, or lack support for democratic values [5,32].

Support for democratic values is measured by combining responses to four questions. The questions asked respondents “how important” they view each of the following traits in a government: “competition among many political groups,” “participation in politics is limited to people who understand the issues,” “citizens in the minority should have the same rights as citizens in the majority,” and “everyone should support the government’s work rather than criticize it.” Higher values indicate more support for democratic values.

Racial resentment is measured by combining respondent’s responses to the standard racial resentment and denial of racism questions: “Generations of slavery and discrimination have created conditions that make it difficult for blacks to work their way out of the lower class,” “I resent when Whites deny the existence of racial discrimination,” “Whites get away with offenses that African Americans would never get away with,” and “White do not go to great lengths to understand the problems African Americans face.” Higher values indicator greater racial prejudice.

Threat perceptions of extremist groups is measured by combining responses to questions asking respondents “how much do you agree with each statement?” … “Extremist groups are” … “dangerous to society,” “a threat to the American way of life,” “gaining power in American politics,” and “infiltrated American institutions of power.” Higher values indicate a perception that extremist groups are more threatening.

Ethnocentrism is measured by combining two questions asking respondents if they agree that “our culture would be much better if we could keep people from different cultures out,” and “there are many cultures in which life is as good as ours.” Responses are coded where higher values indicate greater ethnocentrism or out-group hostility.

The role of partisanship and ideology is less defined in the literature with people on the left and right exhibiting intolerance in different contexts [11,31]. Partisanship is measured with the question, “generally speaking, do you think of yourself as a Republican, Democrat, an Independent, or something else?” A question branch places respondents into one of seven categories ranging from “strong Democrat” to “strong Republican.” Higher values on the partisanship scale indicate greater affiliation with the Republican Party.

Political ideology is measured by asking respondents, “how would you describe your own political viewpoint?” Responses range on a five-point scale from “very liberal” to “very conservative.” Higher values on the ideology measure indicate greater conservatism.

All models control for each of these factors along with the respondent’s gender, age, educational level, race (white, non Hispanics are the baseline category), and social media use. Gender is coded 0=woman and 1=man. Educational level is a six-point scale ranging from no high school degree to a graduate degree. Social media use variable ranges from 0 to 5 with higher values indicating greater daily social media usage.

Findings

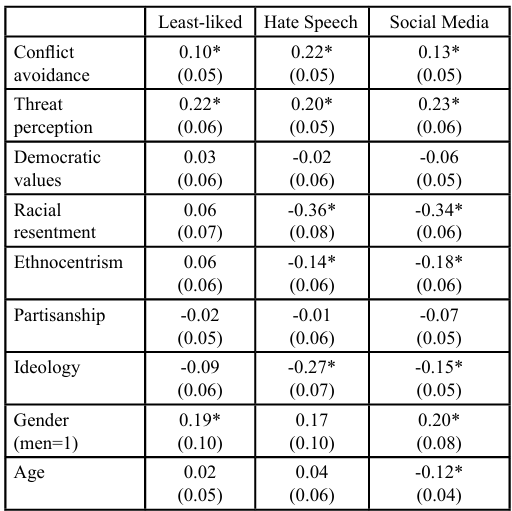

Table 1 reports ordinary least squares regression estimates for each type of speech restrictions. All variables are standardized to ease comparison of coefficients.

Support for government censorship of the respondent’s least-liked group is correlated with conflict avoidance. The conflict avoidance coefficient is positive and statistically significant indicating that people who have little appetite for conflict are more likely to support censorship by the government. Moreover, the coefficient estimate suggests the effect of conflict avoidance on support for censorship is about half of the size of the threat variable, which many view as the most important factor that drives political intolerance [5]. Racial resentment and ethnocentrism show no relationship with censorship in this context. This is consistent with existing studies using the least like methodology and likely due to the questions asking about many groups that lack racial content.

Hate speech rules by public universities also fall within the domain of government censorship, but this question is more general and doesn’t reference the respondent’s least-liked group. The conflict avoidance coefficient is positive and statistically significant indicating that support for public colleges and universities to place restrictions on speech increases the more someone prefers to avoid conflict. The conflict avoidance coefficient shows a similar effect on support for censorship as threat perceptions and political ideology. The latter shows conservatives are less likely than liberals and moderates to support regulations on hate speech.

Calls for social media companies to censor speech represent a departure from speech that is protected by the First Amendment. Yet, conflict avoidant people continue to be more likely to support censorship in this context. The conflict avoidance coefficient is positive and statistically significant indicating people who avoid conflict are more likely to support the censorship of speech by private social media companies. Table SI2 in the Supporting Information shows this is the case for each social media censorship question except for censoring sexual harassment speech which does approach statistical significance (p<.07). Overall, we find support for the idea that conflict avoidant personality types are more likely to support the censorship of speech.

Counterargument Response

Asking respondents to reconsider their initial position began at the end of the post-election wave of the 2020 CES by asking respondents, “Do you favor or oppose the government banning of symbols that represent hatred toward racial and religious groups?.” Responses range on a six-point scale from “strongly favor” to “strongly oppose.” Responses to this question serves as the respondent’s initial opinion. A majority (69%) of Americans support the ban. Those supporting the ban held strong opinions with 36% strongly favoring it compared to 14% who somewhat favored it. Among those opposed, only 10% strongly opposed it.

A respondent’s initial opinion-serves as a starting point in an attempt to push respondents in another direction. Those answering in support of censoring hate symbols were then given a counterargument to their initial opinion and asked to reconsider. Sniderman and Grob [33] refer to this as a post-decision research design since the counterargument treatments are specific to the respondent’s initial response.

The counterargument stated that “the banning of symbols” would “be ineffective since people would create new hate symbols.” Those who initially opposed the censoring of hate symbols were given a different counterargument and ask to reconsider. This counterargument stated that “the banning of symbols” would “be effective at strengthening traditional values or morality and respect.” Given that information emanating from an in-group is more persuasive than uncredited information [34], each counter-argument is attributed to the respondent’s self-selected partisan in-group identified in the pre-election wave of the survey. Analyses show that the in-group does not shape the propensity for attitude change among respondents. Following each counterargument, respondents were asked the identical question that measured their initial response, “Do you favor or oppose the government banning of symbols that represent hatred toward racial and religious groups?.” This is their post-argument opinion or second thought.

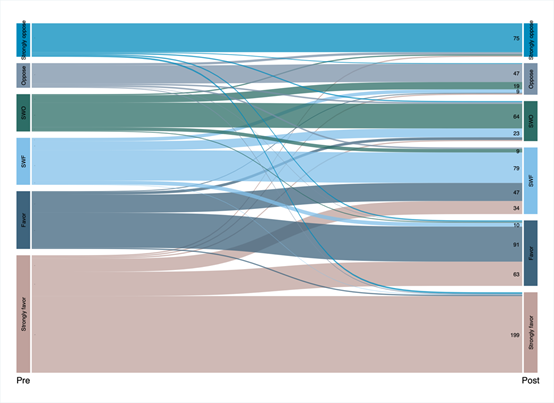

Figure 1 shows the movement from people’s initial response (pre) and their response after given a counterargument (post). Although most people stay in their original position, there is movement across categories. For instance, 63 respondents with the most intense or hardened initial response move from the “strongly favor” category into the “favor” category after a counterargument suggesting censoring hate symbols would be ineffective. Another 34 move into the “somewhat favor” category, while another 30 moves into one of the three oppose responses. The most movement comes from respondents initially responding that they “somewhat favor” the ban who give a “somewhat oppose” or “oppose” response after the counterargument. Overall, 32% of respondents changed at least one category following the counterargument with only 5% of respondents experiencing a backlash against the counterargument. Of those experiencing a backlash, further probing shows it is equally common among those that initially favor the ban (5%) as it is among those initially opposing the ban (5%).

The difference in the distributions of the ordinal responses to the initial thought and second thought are compared using a non parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The test shows a statistically significant difference in the distribution of responses among those initially favoring censorship (z=12.51, p<.00). Respondents initially giving a more favorable response to the question about banning hate symbols (Mean=1.68, SE=.03, n=577) became less favorable toward the ban (Mean=2.13, SE=.04, n=577) after receiving a counterargument, z=7.41, p<.00. Although most of the attitude change are shifts to an adjacent category, 8.6% of those initially favoring censorship moved into a position of opposing censorship.

A second Wilcoxon sign-ranked test fails to show a statistically significant difference in the overall distribution of initial and second responses among those who initially opposed censorship (z=1.02, p<.30). However, respondents initially giving a less favorable response to the question about banning hate symbols (Mean=4.95, SE=.05, n=249) became slightly more favorable toward the ban (Mean=4.77, SE=.07, n=248) after receiving a counterargument that suggested a ban would be effective, z=1.92, p<.05. Similar to those who favor censorship, most of the movement is to an adjacent category with 10% of respondents initially opposing censorship moving toward favoring it.

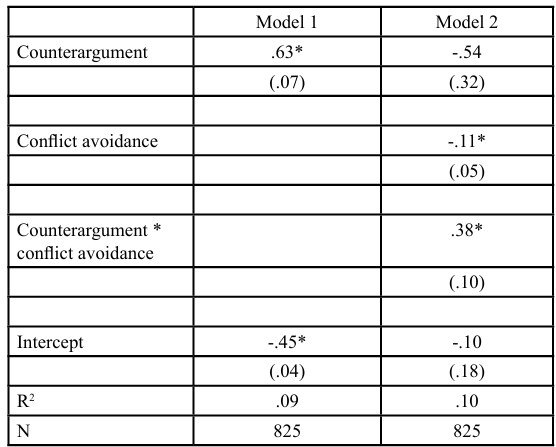

Table 2 shows estimates of the degree of attitude change (pre counterargument opinion– post-counterargument opinion). The outcome variable ranges from -5 (a 5-category shift toward free speech) to 5 (a 5-category shift toward censorship) with 0 representing respondents experiencing no attitude-change. The counterargument variable indicates whether the respondent received a counter attitudinal argument that favors censorship (1) or an argument that opposes censorship (0).

Model 1 shows an estimate of the counterargument. Respondents receiving an argument that censorship would be effective at restoring civility and morality (the favors censorship counterargument) increased support for censorship relative to respondents receiving the counterargument against censorship. In other words, it has the intended effect of increasing support for censorship. However, the model provides estimates of the polarizing effect of both counterarguments in relation to each other which may accentuate the effect of either argument.

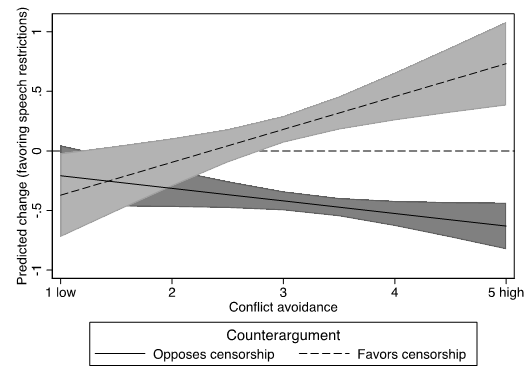

Table 2, model 2 examines the moderating role that conflict avoidance has on the relationship between the counterargument and attitude change. The insignificant intercept indicates that at the lowest levels of conflict avoidance, respondents receiving a counterargument that censorship is ineffective do not experience attitude change. This is confirmed in Figure 2 where the relationship between each argument and respondent’s change in expressed support for censorship is plotted across the conflict avoidance variable. In the absence of conflict avoidance (or lowest levels on the variable), respondents receiving an argument opposing censorship fail to experience attitude change. People who do not have a problem with conflict have little reason to change their belief to avoid conflict with the counterargument.

The conflict avoidance coefficient shows the effect of conflict avoidance among respondents receiving the argument opposing censorship. The coefficient is negative and statistically significant consistent with the expectation that conflict avoidance is associated with a greater susceptibility to attitude change. Respondents receiving an argument to oppose censorship increased their expressed opposition to censorship. This is shown in Figure 2 for values of conflict avoidance of 2 and above.

The results suggest something different for respondents receiving an argument in favor of censorship. The counterargument coefficient is negative (-.57) and approaching statistical significance (p<.08) suggesting respondents at the low end of the conflict avoidance variable who receive the argument in favor of censorship are less likely to favor censorship. Instead, they move in the opposite direction opposing censorship. The marginal effect of the backlash effect is statistically significant (p<.03) as shown in Figure 2. Moreover, the favor argument has no effect on respondents with values between 1 and 3 on the conflict avoidance variable. Once past the midpoint of the conflict avoidance variable, the argument in favor of censorship has its intended effect of moving respondents into changing their attitude toward favoring censorship. This is consistent with the positive and statistically significant interaction coefficient in Table 2. Overall, conflict avoidance relates to a more pronounced degree of attitude change in the presence of the counterargument.

In order to test if conflict avoidance has a greater effect on attitude change when respondents receive the argument opposing censorship versus the argument favoring censorship, an equality of coefficients test is performed on the difference in the slopes shown in Figure 2. The test confirms H3 that conflict avoidant types are more willing to move in favor of censorship than against it, F(1, 821)=12.51 (p<.00).

Conclusion

The study of free speech and tolerance more broadly has focused on the role of democratic norms and whether citizens feel threatened by groups they dislike. This study extends our knowledge of support for free speech by describing the role that a conflict avoidant personality can play in orientating someone toward the regulation of speech. The regulation of controversial speech has been argued to be a means by which a conflict avoidant person can minimize their exposure to conflict. Empirically, all three models show support for this argument. When each component of the dependent variables used in this study are examined individually, conflict avoidance relates to censorship in 8/10 models (see supporting documentation). Thus, the association between conflict avoidance and censorship appears robust.

The relationship exists for both instances when censorship is by the government and in instances when censorship is by private sector actors. Although the latter is not protected under the First Amendment, public thinking about free speech and censorship appears to have extended beyond government restrictions of speech and into approving/disapproving of how private actors regulate speech. This again points to free speech attitudes that are not grounded in principles---such as the Bill of Rights---but instead driven by immediate fears, needs, and goals.

The results also shed new insight into attitude change. There is evidence that conflict avoidant personality types are more likely to express a change in their attitude when given a counterargument to their initial opinion. The least conflict avoidant types receiving the counter-attitudinal argument in favor of censorship demonstrated a slight backlash. The desire to engage rather than avoid conflict might help explain why some people experience a backlash in political discussions more broadly---an explanation that has eluded scholars [35,36]. One remaining puzzle from this study is the extent the observed attitude change represents real attitude change or merely an expressed preference meant to quell conflict. Theoretically, the latter seems more plausible given that the goal of conflict avoidant people is to eliminate the immediate conflict. But the willingness of conflict avoidant people to support censorship---which seems like a permanent solution---might suggest enduring attitude change.

Competing Interest:

The authors of this research declare no competing interest regarding this study.

References

Stouffer, Samuel Andrew. (1955). Communism, conformity, and civil liberties: A cross-section of the nation speaks its mind. Transaction Publishers. View

Feezell, Jessica T., Meredith Conroy, Barbara Gomez Aguinaga, and John K. Wagner. (2023). “Who Gets Flagged? An Experiment on Censorship and Bias in Social Media Reporting.” PS: Political Science & Politics, 56(2): 222-226. View

Harell, Allison. (2010). “The Limits of Tolerance in Diverse Societies: Hate Speech and Political Tolerance Norms Among Youth.” Canadian Journal of Political Science, 43(2): 407-432. View

Chong, Dennis, Jack Citrin, and Morris Levy. (2024). “The Realignment of Political Tolerance in the United States.” Perspectives on Politics, 22(1): 131-152. View

Marcus, George E., Elizabeth Theiss-Morse, John L. Sullivan, and Sandra L. Wood. (1995). With Malice Toward Some: How People Make Civil Liberties Judgments. New York: Cambridge University Press. View

Schleiter, Petra, Margit Tavits, and Dalston Ward. (2022). “Can Political Speech Foster Tolerance of Immigrants.” Political Science Research and Methods, 10(3): 567-583. View

Djupe, Paul A., and Brian R. Calfano. (2013). “Religious Value Priming, Threat, and Political Tolerance.” Political Research Quarterly, 66(4): 768-780. View

Peffley, Mark, Omer Yair, and Marc L. Hutchison. (2024). Political Research Quarterly, 77(1): 30-44. View

Gross, Kimberly A. and Donald R. Kinder. (1998). “A Collision of Principles: Free Expression, Racial Equality and the Prohibition of Racist Speech.” British Journal of Political Science, 28(3): 445-471. View

McClosky, Herbert and Alida Brill. (1983). The Dimensions of Tolerance: What Americans Believe about Civil Liberties. Sage Foundation. View

Neuner, Fabian G. and Mark D. Ramirez. (2023). “Evaluating the Effect of Descriptive Norms on Political Tolerance.” American Politics Research. View

Eisenstein, Marie A. and April K. Clark. (2014). “Political Tolerance, Psychological Security, and Religion: Disaggregating the Mediating Influence of Psychological Security.” Politics and Religion, 7: 287-317. View

Harell, Allison, Robert Hinkley, and Jordan Mansell. (2021). “Valuing Liberty or Equality? Empathetic Personality and Political Intolerance of Harmful Speech.” Frontiers in Political Science, 64. View

Barker, Tyson V., Buzzell George A., and Fox Nathan A. (2019). “Approach, avoidance, and the detection of conflict in the development of behavioral inhibition.” New Ideas Psychology, 53(April): 2-12. View

Elliot, Andrew J. (1999). "Approach and avoidance motivation and achievement goals." Educational Psychologist, 34(3): 169 189. View

Tooby, John, and Leda Cosmides. (1990). "The past explains the present: Emotional adaptations and the structure of ancestral environments." Ethology and Sociobiology, 11(4-5): 375-424. View

Zajonc, Robert. (1998). “Emotion.” In Daniel T. Gilbert, Susan Fiske, and Gardner Lindzey (Eds), The Handbook of Social Psychology, (4th ed., pp. 591-632). New York : McGraw-Hill. View

Cain, Christopher K. (2019). "Avoidance problems reconsidered." Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 26(April): 9-17. View

Elliot, Andrew J., and Todd M. Thrash. (2010). "Approach and avoidance temperament as basic dimensions of personality." Journal of Personality, 78(3): 865-906. View

Hofmann, Stefan G. (2007). "Treating avoidant personality disorder: The case of Paul." Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 21, no. 4: 346-352. View

Bates, J. E. (1987). Temperament in infancy. In J. D. Osofsky (Ed.), Handbook of infant development (2nd ed., pp. 1101 1149). John Wiley & Sons. View

Henderson, Heather A., and Theodore D. Wachs. (2007). "Temperament theory and the study of cognition–emotion interactions across development." Developmental Review, 27(3): 396-427. View

Roth, Susan, and Lawrence J. Cohen. (1986). "Approach, avoidance, and coping with stress." American Psychologist, 41(7): 813-819. View

Dailey, Rene M., and Nicholas A. Palomares. (2004). "Strategic topic avoidance: An investigation of topic avoidance frequency, strategies used, and relational correlates." Communication Monographs, 71(4): 471-496. View

Afifi, Walid A., and Laura K. Guerrero. (2000). "Motivations underlying topic avoidance in close relationships." In Sandra Petronio (ed), Balancing the Secrets of Private Disclosures, (pp.165-180). New York: Psychology Press. View

Berger, Charles R. (1993). "Uncertainty and Social Interaction." Annals of the International Communication Association, 16(1): 491-502.View

Olson, James M., and Mark P. Zanna. (1993). “Attitudes and Attitude Change.” Annual Review of Psychology, 44(1): 117-154. View

Zaller, J. R. (1992). The nature and origins of mass opinion. Cambridge University Press. View

Watt, Susan E., Gregory R. Maio, Geoffrey Haddock, and Blair T. Johnson. (2008). "Attitude functions in persuasion: Matching, involvement, self-affirmation, and hierarchy." In William D. Crano and Radmila Prislin (eds), Attitudes and attitude change, (pp. 189-211). New York: Taylor and Francis. View

Schaffner, Brian, Stephen Ansolabehere, and Sam Luks. (2021). “Cooperative Election Study Common Content, 2020. View

Sullivan, John L., James Piereson, and George E. Marcus. (1979). “An Alternative Conceptualization of Political Tolerance: Illusory Increases 1950s-1970s. American Political Science Review, 73(3): 781-794. View

Carlos, Roberto F., Geoffrey Sheagley, and Karlee L. Taylor. 2023. "Tolerance for the Free Speech of Outgroup Partisans." PS: Political Science & Politics 56(2): 240-244. View

Sniderman, Paul M. and Douglas B. Grob. (1996). “Innovations in Experimental Design in Attitude Surveys.” Annual Review of Sociology, 22: 377-399. View

Tankard, Margaret E., and Elizabeth L. Paluck. (2016). “Norm Perception as a Vehicle for Social Change.” Social Issues and Policy Review, 10(1): 181-211. View

Lau, Richard R. (1985). "Two explanations for negativity effects in political behavior." American Journal of Political Science, 29(1): 119-138. View

Roese, Neal J., and Gerald N. Sande. (1993). "Backlash effects in attack politics." Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 23(8): 632-653. View