Journal of Political Science and Public Opinion Volume 3 (2025), Article ID: JPSPO-123

https://doi.org/10.33790/jpspo1100123Research Article

Hamas & Islamist Radicalism: The Problem of Hamas/ISIS Comparisons

Brian Mello*, Spencer Hallagan, Drew Hynes and Natalie Winters

Department of Political Science, Muhlenberg College, 2400 Chew Street; Allentown, PA 18103, United States.

Corresponding Author: Brian Mello, Professor, Department of Political Science & Associate Dean of Faculty Development, Muhlenberg College, 2400 Chew St. Allentown, PA 18104, United States.

Received date: 08th April, 2025

Accepted date: 05th June, 2025

Published date: 07th June, 2025

Citation: Mello, B., Hallagan, S., Hynes, D., & Winters, N., (2025). Hamas & Islamist Radicalism: The Problem of Hamas/ ISIS Comparisons. J Poli Sci Publi Opin, 3(1): 123.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Abstract

After the Hamas attack on Israel in October 2023 comparisons between Hamas and ISIS were often part of political rhetoric. This paper examines similarities and differences between the versions of Islamist radicalism that inform the ideology and praxis of Hamas and ISIS in order to provide sound empirical reasons to be skeptical the rhetorical equivalency between the two groups. By examining core elements of radical Islamist political ideologies including jihad, takfir, and anti-colonialism, as well as conducting analysis of the ways in which Hamas and ISIS publicly represented violence, we highlight important ways the Islamist practices of Hamas and ISIS differ. In the end, this analysis points to more productive ways for studying Islamist political ideologies.

Keywords: Hamas, ISIS, Islamism, Jihad, Anti-colonialism

Introduction

Since Hamas attacked Israel on October 7, 2023 a number of high-profile American and Israeli political figures have framed Hamas by equating the Palestinian organization with the Islamic State. Former US Secretary of Defense, Lloyd Austin, for example, described Hamas’s violence as “worse than what I saw with ISIS.” Prime Minister Netanyahu declared, “Hamas is ISIS. And just as the forces of civilization united to defeat ISIS, the forces of civilization must support Israel in defeating Hamas.” Influential commentators on foreign policy and international relations, too, have advanced ISIS/Hamas comparisons. Max Boot, for example, said, “Hamas is emulating ISIS’s horrors,” and former Israeli intelligence official Avi Melamed declared, Hamas, like al-Qaeda and ISIS, advances a genocidal agenda.”

While these comparisons may serve clear political purposes, and are deemed appropriate by some [1], they have also been the subject of a number of academic and intellectual critiques [2]. We explore the radical Islamist ideologies and political practices developed by both Hamas and the Islamic State in order to provide a more nuanced understanding of the ways in which radical Islamist ideologies and practices operate–and in the process explore important similarities and differences that might contribute both to more nuanced and forms of public discourse, and point to better ways for political science to study radical Islamist politics.

In this paper, we take up several linked research questions including: How are core practices that define radical Islamist politics present/ represented in Hamas and ISIS? How, for example, does each group understand the concept of jihad (and its limits)? How does ideology and praxis operate to shape national or transnational political identity? How do questions of colonialism shape the ideologies and practices of Hamas and ISIS? Does anti-colonialism function in similar or different ways? In addressing these questions the analysis here focuses on several core texts produced by Hamas, and by Abu Musab Zarqawi and Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, key ideological leaders in the rise of what became the Islamic State but first emerged in the insurgency that responded to the US invasion of Iraq in 2003. In addition, we analyze a variety of images and videos produced by both Hamas and ISIS. Our analysis, thus, blends interpretive analysis of images and texts with elements of more positivist content analysis examining consistency and change in way these groups frame themselves and their political projects.

We begin by outlining the ways in which Hamas and ISIS display some of what has been identified in literature on Islamist radicalism as its core features. One element of this is the way in which contemporary Islamist radicalism represents an example of an anti-colonial ideological project. Subsequently, we turn to a key element of anti-colonialism that permeates most forms of Islamist radicalism since the mid-twentieth century, the waging of violent resistance. Here, we unpack both the different conceptions of jihad that emerge within Hamas and ISIS thinking, and examine the ways in which both groups write about, carry out, and depict their own violent practices. In the final section we outline some implications of the similarities and differences that emerge from such a close reading of the ideological practices of ISIS and Hamas, and discuss both limitations of this analysis, as well as areas for expanding this research.

Understanding Islamist Radicalism as Political Ideology

Radical Islamist ideologies have been defined by commonly identified traits that occur in many groups but are not limited to the following: concepts like traditionalist understandings of Islam as a binding form of identity, practices like jihad and takfir, and a focus on anti-colonialism. These concepts are broad common themes that radical Islamist groups share to some degree. Yet, since various Islamist groups like Hamas and ISIS have different goals and histories, specific forms of Islamist ideology differ in many ways.

In the introduction to his book Salafi-Jihadism: The History of an Idea, Maher identifies concepts that are common in radical Islamist ideologies, including:

five essential and irreducible features of the Salafi-Jihadi movement: tawhīd [the belief that there is no god but Allah], hakimiyya [the belief in the sovereignty of Allah] , al-wala' wa l-baraa' [loyalty to Islam and the rejection of all that disavows Islam], jihad [a conception of Islamic‘just war’], and takfir [the ability to excommunicate from the Islamic community, or to define individuals or groups as apostate]. These five features appear repeatedly in literature from both ideologues and groups that espouse a Salafi-Jihadi ideology. The literature consistently references these ideas and demonstrates they have undergone significant ideational mutation in Salafi-Jihadi understanding. While all of these ideas exist within normative Islamic traditions, and nothing is particularly unique or special about them, they are relevant in this context because the contemporary Salafi Jihadi movement has interpreted and shaped them in unique and original ways [3].

While we use this as a base framing to better understand the difference between Hamas and ISIS, Hamas is not part of the Salafi jihadist movement. Nonetheless, we draw on this framing because we believe this overview of common elements proves useful for thinking about radical Islamism more broadly, not just the Salafist versions of it. Absent from Maher’s understanding of the key elements of Salafi- jihadism is a focus on anti-colonialism as a core element of radical Islamist ideologies and practices. A good deal of scholarship on the resurgence of radical Islamism beginning in the mid-20th century, however, points us toward adding this essential element [4].

Consequently, the four concepts that define radical Islamist ideologies and practices that we concentrate on here include: Islam as a binding form of identity; takfir (or the practice of identifying good/ bad Muslims); anti-colonialism; and jihad. Throughout, our analysis provides a comparison of Hamas and ISIS that focuses on similarities and differences in the way these four elements define ideological beliefs and political practices. This comparative approach enriches our understanding of the unique and shared characteristics of radical Islamist ideologies, and points toward ways for future scholarships to explore continuity and change in radical Islamist politics. Table 1 provides an initial overview of the key ways Hamas and ISIS differ along these four concepts.

Islam, Identity, & the Application of Takfir

Islam is a binding form of identity for Hamas and ISIS. For ISIS, a particularly conservative, Salafist version of Sunni Islam was the primary identity they sought to advance, and that underpinned their violent efforts to upend the state system in the Middle East. When it emerged first in Iraq and later in Syria, ISIS aimed to revive the historical Caliphate, positioning itself as a global focus for Muslims. Early ISIS ideologues expressed a desire to become the location for Muslims around the world to go and relocate. In the “Declaration of Caliphate” al Baghdadi declared:

O Muslims everywhere, glad tidings to you and expect good. Raise your head high, for today - by Allah's grace - you have a state and khiläfah, which will return your dignity, might, rights, and leadership. It is a state where the Arab and non-Arab, the white man and black man, the easterner and westerner are all brothers. It is a khiläfah that gathered the Caucasian, Indian, Chinese, Shãmi, Iraqi, Yemeni, Egyptian, Maghribi (North African), American, French, German, and Australian. . . Therefore, rush O Muslims to your state. Yes, it is your state. Rush, because Syria is not for the Syrians, and Iraq is not for the Iraqis . . . . O Muslims everywhere, whoever is capable of performing hijrah (emigration) to the Islamic State, then let him do so, because hijrah to the land of Islam is obligatory.” [5]

For Hamas, Islam is important to identity, but it is understood as an essential marker of Palestinian, rather than transnational, identity. Palestinian national identity is their main focus as they pursue Palestine's "liberation," not the "liberation" of all Muslims. This distinction between Islam as a marker of shared national identity versus Islam as a form of transnational identity marks an important difference in the way religious identity functions.

The shared, transnational identity of religion plays a unifying role for ISIS as a tool to support ISIS’s goal of countering Western colonial influence globally. ISIS used religion not only as a unifying role in supporting their ideology but also for identifying who is a “true believer” and a “good” Muslim; good Muslims support and declare allegiance to the Islamic State. In their ideology, ISIS defines for itself a lead role for Muslims globally. ISIS uses the concept of takfir to identify, group, and define people who are good Muslims and differentiate them from "bad" Muslims or "nonbelievers." This categorization is pivotal for ISIS as it frames its global identity, segregating supporters from opponents within the Muslim community. Maher describes it in this manner: “For the global jihad movement, it has become a valuable tool for the protection of Islam, a means of expelling those from the faith who are thought to be subverting it from within. As such, in its current constructions, the concept is used to license intra-Muslim violence particularly in highly sectarian environments [6].”

The use of takfir is a tool that ISIS used to justify violence against Muslims that do not support them by putting them into the categories of “nonbeliever”, “bad Muslims”, “good Muslim”, and “true believer.” Thus, for example, in his letter to al-Qaeda leaders, Abu Musab al Zarqawi explained not only how the Americans occupying Iraq were a concern and focus of violence, but he also emphasized that concerns about other Muslims were going to remain regardless of when the Americans left:

They know that, if a sectarian war was to take place, many in the [Islamic] nation would rise to defend the Sunnis in Iraq. Since their religion is one of dissimulation, they maliciously and cunningly proceeded another way. They began by taking control of the institutions of the state and their security, military, and economic branches. As you, may God preserve you, know, the basic components of any country are security and the economy. They are deeply embedded inside these institutions and branches. I give an example that brings the matter home: the Badr Brigade, which is the military wing of the Supreme Council of the Islamic Revolution, has shed its Shi‘a garb and put on the garb of the police and army in its place. They have placed cadres in these institutions, and, in the name of preserving the homeland and the citizen, have begun to settle their scores with the Sunnis. The American army has begun to disappear from some cities, and its presence is rare. An Iraqi army has begun to take its place, and this is the real problem that we face, since our combat against the Americans is something easy. The enemy is apparent, his back is exposed, and he does not know the land or the current situation of the mujahidin because his intelligence information is weak. We know for certain that these Crusader forces will disappear tomorrow or the day after [7].

Here, Zarqawi suggests that western military forces were a fleeting enemy who did not have the support of the Islamic nation and were a temporary thorn in their side. The difference is that Muslims in the Islamic nation understand Middle East politics and have support, and if they challenge the Salafi-jihadists, they will be a more enduring concern: “Bad” Muslims to early ISIS ideologues were more dangerous and therefore justified application of the concept takfir as a policing mechanism for Muslims and justification for internally focused violence.

When we examine important foundational documents, or even Hamas’s positions after moments of intra-Palestinian conflict, it becomes clear that Hamas does not use takfir when it comes to other, even more secular, Palestinian nationalist groups. When Hamas won national council elections in 2006, they did not attack their secular political opponents, who had power before them, for being apostates. Violence that erupted in Gaza was less about who was a who wasn’t a good Muslim than it was about who would control the security apparatus in the Gaza Strip, and once Hamas emerged as the clear victor internal violence was largely curtailed. More recent conflicts between Hamas and Salafist groups in Gaza, which included the raid of a Mosque in 2009 that ended with 24 deaths and around 130 wounded, were also not characterized by the application of takfir, but by Hamas concerns about the emerging appeal of Salafi-jihadist groups within Gaza [8]. If Hamas exhibited the same tendency to deploy takfir doctrine as ISIS, we might reasonably expect a more enduring and violent internal contestation within Palestinian society.

Hamas's ideology seeks, fundamentally, to Islamize Palestinian national identity or to re-center Islam within Palestinian nationalism. Hamas does not use the concept of takfir in support of their cause, and they have generally focused their violent resistance against Israel. From its founding document to its revision in 2017, Hamas outwardly emphasized unity across difference: “The Palestinian people are one people, made up of all Palestinians, inside and outside of Palestine, irrespective of the religion, culture, or political affiliation [9].” The concept of takfir does not align with their movement. Litvak summarizes, “Hamas rejects the Salafi- jihadist concept of declaring Muslims as apostates (takfir), if they fail to follow the strict Salafi interpretation, and the declaration of jihad against irreligious Muslim rulers [10].”

Anti-colonialism in Hamas & ISIS

The deployment of anti-colonial rhetoric varies significantly between ISIS and Hamas, influencing their respective ideological narratives and operational strategies. ISIS advocated for the establishment of a caliphate to unify the Muslim world, positioning itself as a force erasing the legacy of colonialism across the Middle East. Islamic State leaders dedicated a good deal of thinking and propaganda (including an English-language video bulldozing the border between Iraq and Syria), for example, to the erasure of ‘the Sykes-Picot borders.’ Hamas emerged out of and is affiliated with the Muslim Brotherhood, which since its emergence in Egypt in 1928 has advanced a version of anti-colonialism that has been rooted more within national contexts—seeking to promote Islam within particular societies as a pathway toward Islamicizing states. As the case of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt demonstrates, anti-colonialism has variously involved advocacy of violent practices, as well as their rejection in favor of broader social, political, and educational tactics.

Anti-colonialism is more narrowly, less globally focused in Hamas’s case, and whereas ISIS’s anti-colonialism was defined by a consistent focus on artificial borders drawn at the end of World War I, Hamas’s framing of anti-colonialism has changed in some notable ways across time. In Hamas's original charter in 1988, anti- colonialism took on more clearly anti-Semitic rhetoric, but this was somewhat tempered in its "2017 Document of General Principles and Policies.” Some of the change may owe to differences in the audience for each ideological document; while the original charter was internally focused, the revision may have in mind a broader, international audience as well. Keywords consistently used in the charter concerning how Hamas framed and wrote about Israel/ colonialism include: Zionist (sixteen times), Jew (fourteen times), Nazi (four times), enemy (nineteen times), and invasion (ten times). This suggests that the framing in the charter focused more centrally on Jewishness and religious difference as a source of colonial invasion. In the original charter, Hamas leaned into anti-Semitic conspiracy theories of how Jewish people control the media:

The enemy planned long ago and perfected their plan so that they can achieve what they want to achieve, taking into account effective steps in running matters. So they worked on gathering huge and effective amounts of wealth to achieve their goal. With wealth they controlled the international mass media—news services, newspapers, printing presses, broadcast stations, and more. With money they ignited revolutions in all parts of the world to realize their benefits and reap the fruits of them. They are behind the French Revolution, the Communist Revolution, and most of the revolutions here and there which we have heard of and are hearing of. With wealth they formed secret organizations throughout the world to destroy societies and promote the Zionist cause; these organizations include the Freemasons, the Rotary and Lions' clubs, and others. These are all destructive intelligence-gathering organizations. With wealth, they controlled imperialistic nations and pushed them to occupy many nations to exhaust their (natural) resources and spread mischief in them [11].

In the “2017 Document of General Principles and Policies” keywords that were used in identifying the enemy were: Jew (six times) and Zionist (nineteen times). In other words, the 2017 document focused on Zionism rather than Jewishness, and this may be explained by efforts to gain external legitimacy as it suggests it is Zionism as a colonial nationalism, rather than Jewishness and religious difference that is the driving source of anti-colonial grievance. Nonetheless, across time, the primary focus of anti-colonialism for Hamas has to do with Israel rather than western interference in the region or Islamic world more broadly.

Understanding the different focus of anti-colonialism helps foreground a critical difference between ISIS and Hamas. The idea of a global caliphate follows from ISIS’s transnational identity and belief that western-drawn borders need to be erased in order to achieve global religious unity. Hamas, on the other hand, has confined its territorial ambitions to the establishment of a Palestinian state, which has meant at various points the desire to control all of the space in Israel and the Palestinian territories, and at times the acceptance of a Palestinian state based on a variety of negotiated agreements [12].

Resistance is Always Violent

One of the main reasons why anti-colonial movements often engage in violent measures is due, in part, to understandings about the way colonialism operates that were most notably advanced by Fanon in The Wretched of the Earth. For Fanon, decolonization is always a violent process because the colonizer almost never gives up their power voluntarily, and the violence of colonial rule shapes, in turn, the violence of anti-colonial resistance. Colonization, Fanon argues, involved the violent negation of the very humanity of the colonized. Violent anti-colonialism throws this system entirely on its head; it offers a rejection of colonialism and helps re-establish the agency and humanity of the colonized.

These ideas are amplified by the violence that takes place from groups such as ISIS and Hamas, which often takes the form of terrorism. Anti-colonial violence advances a number of goals simultaneously. On the one hand, anti-colonial violence serves to draw in more supporters by demonstrating a capacity to effectively resist. The logic of anti-colonial violence is also designed to raise the costs on the colonizer and incentive decolonizing changes. More recently, with the publication of the Jihadist text, The Management of Savagery, violence was designed to provoke a response from western powers that would unmask their real, violent colonial nature [13]. We can see each of these aspects of anti-colonial violence at work in Hamas’ attack on October 7. Indeed, the attack was simultaneously designed to enhance internal legitimacy; to provoke the Israeli government to respond violently; to raise the costs on Israel for abandoning the two state solution; and to disrupt broader Arab normalization with Israel without first addressing Palestinian claims to statehood. This is somewhat different than the way the violence of the Islamic State works. While both groups sought to recruit new members and gain legitimacy through their violence, ISIS sought to recruit new fighters who are inspired to take up arms and join the caliphate. They deployed violence against foreigners, Yazidis, Kurds, Shi’ite Muslims, the Syrian and Iraqi militaries, etc. with goals of causing people to flee or capitulate. And, they relished western military campaigns as a means to castigate colonialism and build popular support, a trope at the center of their 23-minute video on the execution of a Jordanian air force pilot [14].

For virtually any anti-colonial movement, Fanon suggests there is often a desire to return to the world that existed before the colonial entity took power that defines search for a viable post-colonial identity politics. The Islamic State and Hamas both share this desire to return to the world that existed before the onset of colonialism, but what that looks like for these groups is vastly different. ISIS’s vision was one based on the rejection of the modern state system, the erasure of borders, and the establishment of a caliphate based on an interpretation of how society was and ought to be organized to resemble the time of the Prophet Muhammed. For Hamas, the goal is to return to a time of Palestinian sovereignty prior to the establishment of Israel, but this neither entails a rejection of modern forms of governance (e.g. democracy) nor full rejection even of the possibility of a solution that leaves a state of Israel in place, and it certainly doesn't entail a full rejection of the modern state system in the broader region.

Understanding the Role of Jihad & Violent Practices

The concept of jihad is central to both Hamas and ISIS, however it gets articulated in differing ways. As Maher suggests, "As an idea, jihad is iridescent and opaque [15].” What types of actions define the focus and scope of jihad depends on who is using it and their goals; Hamas's use of jihad is different from ISIS. Jihad, for ISIS was unbound by constraints, aimed at enemy civilians and militants with equal ferocity, and almost exclusively militant, whereas Hamas has outlined (if not always followed) some limitations on permissible violence, engaged in a variety of violent practices, demonstrated an ability to suspend certain violent practices, and offers nom-militant pathways for engaging in jihad.

In one of his narrative defenses of executions, Al-Zarqawi frames conflict as an existential struggle for the soul of Islam, emphasizing ISIS's approach to jihad. True believers are depicted as needing to commit fully to defending their faith and way of life against perceived threats. His discourse seeks to mobilize support by appealing to religious conviction, historical grievance, and a sense of urgency about the perceived dangers facing the Muslim community. One’s authentic Islamic bona fides depend on collective engagement in ISIS violence [16]. In terms of martyrdom, ISIS intertwines this concept with jihad, believing that those who die in the fulfillment of obligations to wage jihad will achieve martyrdom and eternal bliss, thus fulfilling their spiritual destiny. This belief is a core component of their narrative, justifying acts of extreme violence.

Similarly, Hamas views jihad as essential, arguing in foundational documents that "There is no solution to the Palestinian question except through Jihad." Hamas's goals have changed and evolved over time, though. The jihad pursued by Hamas has both short- and long-term goals. On the strategic level, it aspires to drain the energies of “the Zionist enemy,” humiliate it, sow fear among its ranks, and eventually bring about the disintegration and total collapse of the Zionist state. In the short run, it seeks to deprive Jews of a life of comfort when Palestinians live as dispossessed refugees and to take revenge for the killing of Palestinians [17]. Hamas’s violence has taken on a variety of forms over time including the deployment of suicide bombing (both in the early 1990s and with much greater frequency during the second—post-2000—intifada), the use of rockets (a tactic that was first widely deployed between 2006 and 2014 after the Israeli blockade of Gaza and building of security fences), and the kidnapping of Israeli soldiers used to bargain for the release of Palestinians detained in Israel (most famously the case of Gilad Shalit, who was detained from 2006 until 2011). Moreover, unlike ISIS, Hamas has, at times (such as during the early Oslo peace process) demonstrated a willingness and ability to suspend violent jihadist tactics based on political calculations [18].

The existing literature on the methods of violence and the strategy behind its mass deployment used by the Islamic State, Hamas, and other jihadist groups focuses on the symbolic and strategic nature of an individual group's actions. By carefully examining, analyzing, and comparing different methods of violence employed by both Hamas, particularly during the October 7 attack, and ISIS, we can gain valuable information on the groups' ideological differences.

Displaying the atrocities and violence of war is not unique to the 21st century. In fact, the first known attempt at war photography was in 1853 during the Crimean War [19]. Since then, publics thousands of miles away from a physical war have had access to the imagery of violence and suffering of wartime. However, in recent years, this imagery has evolved with new media technology and the growth of visual interconnectivity around the world [20]. This is exemplified by the widespread distribution of ISIS’s beheading videos and the media innovations extremist groups are using to display their violence to millions of people around the world. With the growth in Jihadist media and propaganda came a new wave of access to these groups for researchers to explore. Whiteside [21] and Dauber and Robinson [22] offer interesting research on the video production of propaganda and the Islamic State’s media boom in the 2000s. Whereas Friis, Mello, and Nanninga [23] focus on the symbolic nature and visibility of the Islamic State’s beheading videos. Increasingly researchers look closely the propaganda of jihadist groups as a gateway to their ideology and practices [24].

While not showing the actual killing, screen grabs from various beheading videos became a recurring visual representation of ISIS, despite initial debates on how to document these events without reiterating the crime and exposing the victim. Friis and Mello contend that ISIS distinguishes itself through innovative, high-quality execution video productions designed to attract viewers worldwide. The videos, depicting the executions of Western civilians and enemy soldiers, are meant to “entertain as much as to instill fear, depending on the viewing audience [25].” ISIS focuses on symbolic violence depictions and uses social media to broadcast its violent successes, perfecting the practice of displaying violence.

Nanninga notes that the main reason provided for the execution videos are the American and British airstrikes in the Middle East, but adds that the group’s violent practices have been heavily influenced and ritualized by the Quran. He explains that “in the case of the Islamic State’s executions, it is important to note that the organizers have selected a means of execution that is established in Muslim tradition… Decapitation can be legitimized by Quran verses such as SURA 47:4, which states, “when you meet those who disbelieve, strike their necks [26].” Nanninga also proclaims that the Islamic State’s beheadings resemble the prominent Muslim tradition of the sacrificial slaughter of animals. The rituality and formality of the execution videos can be seen as a distinguishing this element of ISIS violence from its other violent acts.

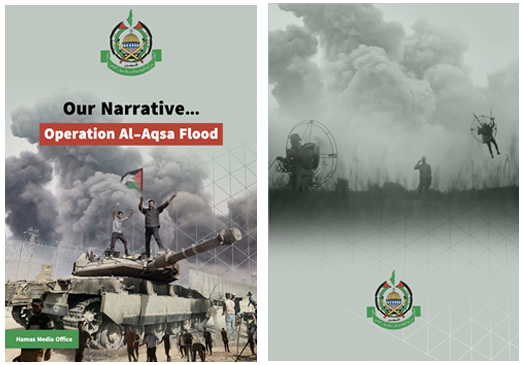

In order to further explore the ideological and practical differences between Hamas and the Islamic State, we focus on images from violence-related media released by each group. First, we examine the front and back cover of “Our Narrative… Operation Al-Aqsa Flood,” an 18-page memo released by Hamas explaining and justifying the October 7 attack on Israel. The cover page features dark smoke rising behind a tall barbed wire fence. The main image shows an abandoned Israeli tank enlarged over unarmed Palestinian men, with two men holding up a “V,” for victory with their fingers, and waving the flag of Palestine on top. The back cover depicts the same smoke clouds and two men landing on makeshift motorized parachutes, with a silhouette of a man saluting in the background. These images, along with the text, provide insight into Hamas’s ideology and desired image.

The imagery chosen by Hamas in this memo vividly captures the essence of the Palestinian struggle for freedom from Israeli oppression. The billowing black smoke in the background of the front cover evokes the relentless air assaults and bombings endured by Palestinians at the hands of Israel. The imposing image of an abandoned tank superimposed over unarmed civilians serves as a stark reminder of Israel's overwhelming economic and military superiority in the region. These symbols encapsulate the broader militarization of the area and the pervasive violence inflicted on Palestinians, portraying Israel as a Western-backed superpower engaging in what some perceive as genocidal [27] actions against the Palestinian people. Hamas extends Palestine’s suffering beyond Israel's use of violence, emphasizing the “open-air prison” narrative imposed by Israel's occupation of Palestine. Through militarized borders, physical barriers, and restrictions on humanitarian aid, Hamas argues that Israel's presence in Palestinian territory is inhumane, leading to the suffering of innocent civilians. This theme is evident in both text and imagery throughout “Our Narrative…” The front cover features a large fence with a hole, symbolizing the barriers Palestinians face. The sixth page shows unarmed Palestinian men confined to a small open-air prison cell, highlighting the plight of those living under occupation. The tenth page depicts a bulldozer tearing through the Israeli border fence, representing the strength of Palestinians to overcome these perceived injustices. These images are intended to galvanize activists and Palestinians worldwide in solidarity against Israeli occupation.

While deliberately resembling the colonial struggle of Palestine, the images also represent and honor the strength of the Palestinian people despite their economic and military disadvantages. The foreground of two unarmed men conquering and proclaiming victory on an Israeli tank on the front cover serves as a symbol of the determination, strength, and power of the Palestinian people and their capabilities. One of the men atop the tank is waving a Palestinian flag, instilling a sense of nationalism and patriotism in all Palestinian viewers. The makeshift paramotors on the back cover boast the group's ability to adapt and overcome the lack of resources instilled upon them by Israel. By showcasing the ability to rise against a Western-backed power despite the lack of resources, Hamas creates a David vs Goliath narrative that instills a sense of pride in all Palestinians and generates sympathy from activists, politicians, and voters in Europe and the United States. After deliberately victimizing themselves and all of Palestine, Hamas seeks sympathy from “free peoples across the world, especially those nations who were colonized… (and) to initiate a global solidarity movement with the Palestinian people and realize the suffering of the Palestinian people [28].” The symbolism of the images used in Hamas’s propaganda justifying their October 7 attacks constructs Palestinians as victims, suffering under colonial Israeli occupation, and instills a sense of pride and nationalism in all Palestinians by asserting an ability to resist this colonialism, all while grasping for sympathy from Western publics.

The choice of imagery released in the memo is deliberate and meaningful, yet it contradicts the civilian videos and eyewitness accounts of the events that occurred that day. While public witness reports depict unrelenting violence and disregard for civilian life, Hamas emphasizes its commitment to avoiding harm to civilians, especially children, women, and the elderly, placing blame on Israel as the main instigator of violence in the region. Hamas states, “Avoiding harm to civilians... is a religious and moral commitment by all the Al-Qassam Brigades’ fighters... Palestinian fighters only targeted the occupation soldiers and those who carried weapons against our people [29].” The group claims that any civilian deaths happened “accidentally” and were coincidental in the action of the war, which is a somewhat dubious assertion when one considers that these very images were synonymous with the assault on the Re’im music festival, where 364 Israeli civilians were killed. It is, in the end, noteworthy that Hamas’s imagery is not designed to amplify their most brutal forms of violence—a stark contrast from ISIS’s execution videos, and even a stark contrast to its own past celebration of its ability to puncture Israeli security through bombings and rocket attacks.

Hamas’s claim to avoid killing civilians and refusal to take responsibility for moments when the targeting of civilians in this post-hoc justification for the October 7 attack is not something likely to emerge from other radical Islamist groups [30]. The Islamic State and Al-Qaeda, for example, justify and deliberately target civilians because they participate in Western democracy, which means they act in a system that inherently discriminates and abuses Muslims worldwide [31]. By claiming to only target military personnel and locations in the October 7 attack, Hamas may be seeking to set itself apart from the image of Islamist organizations in the eyes of Western media and public consideration—particularly given the risk of losing external support were they to emphasize the more brutal forms of violence that occurred during the attack. After all, Hamas believes that in order to overcome the challenges of occupation, Western political actors must stop funding and supporting Israel. Next to a picture from a Free Palestine protest in the United States, Hamas calls upon the US, the UK, and France to “stop providing the Zionist entity with cover from accountability, and to stop dealing with it as a country [32].” Claiming the civilian casualties of October 7 were a mere accident exposes a major difference in ideology and practice between Hamas and the Islamic State.

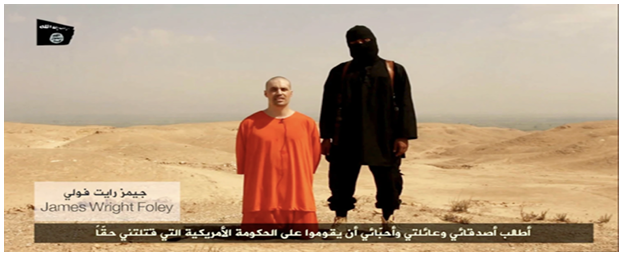

To analyze the Islamic State's use of symbolic violence, here we examine the execution video of American journalist James Foley. The video, titled “A Message to America” and released on YouTube in August 2014, is a visual representation of ISIS’s perceived anti colonial struggle against United States military role in the Middle East. The video opens in silence with a quote from the Quran and quickly transitions to a quote in Arabic and English explaining President Barack Obama’s authorization of military operations and targeted airstrikes to protect American troops. Suddenly the screen goes dark with an electrical surge cutting to the sights and sounds of American ammunition, airstrikes, and engines depicting “American Aggression against the Islamic State [33]” before the screen goes black and the sound silences and “A Message to America” slowly appears.

At the two-minute mark, the video shows a clear, high-resolution image of James Foley. He is kneeling beside his executioner, who is dressed in black with a leather gun holster under his left arm. Foley, with a shaved head and face, barefoot and with his wrists cuffed behind his back, is dressed in an orange jumpsuit. The setting is outdoors, on a bright day, in a dry and arid location. Foley begins to speak a script, presumably written by his executioners, stating “I call on my friends, family, and loved ones to rise up against my real killers: the U.S. government. For what will happen to me is only a result of their complacency and criminality… All in all, I wish I wasn’t American.” After this monologue the screen briefly cuts black again before the next scene where Mohammed Emwazi, known as Jihadi John, speaks in a British accent proclaiming that American military operations interfering with the affairs of the Islamic State is an attack against all Muslim’s worldwide. Emwazi begins to cut Foley’s head in a sawing motion and the video cuts off before any blood is drawn. The video fades out of darkness to the corpse of James Foley lying stomach down in the sand with his severed head resting atop his back. While holding the collar of Steven Sotloff, an American-Israeli journalist and the Islamic State’s next beheading victim, Emwazi directly addresses President Obama stating “the life of this American citizen, Obama, depends on your next decision.” The video ends in similar fashion to the way it started showing frightening images and sounds of American airstrikes and artillery in the Middle East.

The production of this video and the content it contains was deliberately planned and executed by the Islamic State to symbolize the struggle of all Muslims from Western occupation and military operations in the Middle East and to declare themselves as a legitimate global actor equivalent to the United States. The last scene of the Foley video functions as a “horrifying cliff-hanger… showing the executioner together with the next hostage who would be executed if the West would not ‘back off and leave our people alone [34].” Of all forms of executions, ISIS deliberately chose beheadings as it is established in Muslim tradition. The Qur’an states in verse sura 47:4 “when you meet those who disbelieve, strike necks.” While intentionally targeting the West to retaliate and instill fear, the group is also targeting Muslims worldwide by the use of religious tradition and defending their honor as Muslims.

As Clare Gillis notes, the execution of James Foley represents a contrasting moral hierarchy between both target audiences. Gillis writes that “for ISIS, the evil is coalition bombs, (and) the execution of a U.S. or U.K. citizen is barely a drop in the bucket comparison [35].” For the West, the image of a selfless, public serving, and indifferent journalist kneeling helplessly as their government refuses to negotiate with terrorists to save their life is particularly poignant [36]. Decapitation is an extremely personal and intimate form of execution that deliberately “targets the part of the human body responsible for thought, personality, and expressiveness [37].” The choice of beheading as a means for execution goes beyond the Muslim tradition to resemble the stark contrast between the anonymous and reckless Western surgical airstrikes and the courage and heroic act of executing an enemy face to face. The symbolism does not only resemble the specific airstrikes of the US military, but also the persecution of Muslims worldwide and on American soil. The connotation of abuse that the Foley video depicts, intends to unite Muslims worldwide in support of ISIS’s cause and to legitimize their power en route to establishing a caliphate that claims authority over all Muslims.

The portrayal of violence deliberately calculated and deployed by both Hamas and ISIS serve as a gateway for analysis of the similarities and the differences between the groups’ ideology and practices. The Islamic State is a transnational organization with the end goal to establish a caliphate ruling over all Muslims worldwide. Hamas is a nationalistic organization with the end goal of Palestinian liberation. In order to achieve these respective goals, both ISIS and Hamas seek internal and external legitimacy through their violent practices and how they portray them. While they are both seeking legitimacy, they pursue this in different ways. For Hamas, the proclamation that “avoiding harm to civilians, especially children, women and elderly people is a religious and moral commitment by all the Al-Qassam Brigades’ fighters… and that the Palestinian fighters only targeted the occupation soldiers and those who carried weapons against our people [38]” is a declaration of military status. By claiming to avoid civilian casualties and not depicting violent imagery in the memo, Hamas is seeking to alter their perceived image from Islamic extremists recklessly killing innocent people to a legitimate military operation acting on behalf of the Palestinian resistance. Hamas knows that their image in the West must be perceived as such in order achieve liberation.

For ISIS, the “claim of statehood serves as a declaration of equivalence between the US and ISIS [39].” Similar to Hamas, ISIS asserts themselves as an army and state. In the James Foley execution video Enzwami asserts that the US is “no longer fighting an insurgency; we are an Islamic Army and a state that has been accepted by a large number of Muslims worldwide.” By posing as state actors, ISIS equates itself to a global superpower and seeks legitimacy from Muslims worldwide and political actors in the West. Unlike Hamas, ISIS is extremely upfront with their use of violent imagery. Like other Islamist extremist groups, ISIS justifies their targeted killing of Western civilians by iterating the fact that all civilians in a democracy participate in a system that funds and operates the persecution of Muslims worldwide.

In the pursuit of legitimacy as resistance movements and would be state actors, Hamas and ISIS both portray themselves as victims suffering from Israeli or Western occupation and abuse. While Hamas is seeking sympathy from the West, ISIS is seeking sympathy from Muslims worldwide. Both groups create a narrative of heroic struggle in their portrayal of violence. We might surmise that Hamas is deliberately targeting sympathy from political actors in the West because they include an image from a Free Palestine protest in the West and call upon them to speak on behalf of Palestinian liberation. This exposes a key difference between the ideologies and practices of Hamas and ISIS. Hamas is seeking allyship from political actors in the West, whereas ISIS proclaims all political actors in the West as enemies. ISIS achieves the same anti-colonial rhetoric by symbolizing the contrast between the cowardliness of anonymous airstrikes and the intimacy of a beheading. Similar to Hamas, ISIS shows that they do not need many resources to inflict fear and strike back against global superpowers. Using just a knife and a camera, ISIS is able to induce physical harm to a handful of victims but psychological harm to millions of Western viewers.

Both Hamas and ISIS symbolize the anti-colonial struggle and resistance against technologically, economically, and politically superior states. Despite the similarities, the way both groups portray their violent practices in their propaganda greatly differs. ISIS is unmercifully abrupt with their portrayal of violence, while Hamas seeks to hide their harm to civilian life. Every participant in a Western democracy is considered an enemy of ISIS, while Hamas calls upon them to realize the suffering of colonialism and act in sympathy with the Palestinians. As the violent practices of Islamist extremists continue to evolve, it is crucial for activists, politicians, researchers, and others to use the propaganda released by these groups to further analyze differences in the ways in which radical Islamist groups deploy and portray the ways in which they engage in anti-colonial forms of jihad.

Implications & Pathways for Future Research

The analysis in this project takes up suggestions for taking political ideologies as important factors for understanding politics. In her introduction to Dogmas and Dreams, for instance, Nancy Love argues that we can study ideologies as causal structures, focusing on how they explain and cause particular political practices. We can examine, she suggests, how core and supporting concepts flesh out a coherent basis for political action. Alternatively, we can study ideology in order to understand difference and change [40]. For Michael Freeden, political ideologies are a ubiquitous element of political life shaping groups as dynamic, power-wielding, identity bestowing, cultural entities [41]. Yet, Freeden outlines an argument for considering ideologies not as monolithic, but as contested; as changing over time. Political science research, then, ought to be particularly interested in understanding variations in understandings of key political concepts and practices. This analysis of Hamas and ISIS has taken this research agenda seriously.

By focusing on changes in understandings and practices within both groups across time, as well as on the differences between understandings and practices adopted by Hamas and ISIS, this paper contributes to political science scholarship focusing on how points of difference provide critical ways for understanding ideologies and ideological change. Differences in Hamas’s anti-colonialism, for instance, helps us understand how Hamas has changed over time. In addition, despite Hamas’s textual rejection of violence against women and children, the nature of its violence on October 7 highlights the influence of innovative, albeit brutal, violent practices that contributed to ISIS’s battlefield and political successes.

This analysis also highlights the need for scholarship on Islamist radicalism to complicate political and popular interpretations that reduce or obscure the complexity of Islamist politics. The Islamism of Hamas is rooted in Palestinian nationalism, and its anti-colonial struggle is focused on Israel. ISIS, on the other hand, adopts a transnational identity with an anti-colonialism that is more globally focused on the role of the west. Intra-Muslim conflict, which features prominently in the thinking and violent practices of ISIS is markedly absent from Hamas, which instead adopts a narrative of national unity, even despite moments of civil conflict with Fatah. For ISIS, violence is unfettered and the unleashing of savagery is seen as essential for creating the conditions in which the Islamic State could emerge. For Hamas, the reality of moments of violence aside, ideological commitments to the rejection of violence against women, children, and the elderly are repeatedly incorporated into key public documents. In other words, Hamas is not ISIS, and ISIS is not Hamas.

Finally, this analysis suggests that focusing on the relationship between ideology and praxis allows us to contextualize and understand radical Islamist politics in more nuanced ways. We come to understand that particular practices are related to and reinforce beliefs and identities, and that, while all radical Islamist politics share some core elements, the nature of these elements differs quite importantly. The ability to effectively respond to radical Islamist ideologies depends on us having better, more nuanced understandings of the different versions of radical Islamism that underpin political groups.

While we’ve explored this question in a way that seeks to foreground a number of key elements and practices that inform the radical Islamist ideologies of Hamas and ISIS, there are still other areas that are beyond our scope. For example, the understanding of ideological difference and change within radical Islamist politics might fruitfully consider differences in forms of Islamist governance across Hamas and ISIS. In addition, much has already been written about, though not incorporated here, changes in radical Islamism between al Qaeda and ISIS. Finally, it is beyond our scope to fully think about the role of Salafi-jihadist organizations that have emerged as challengers to Hamas, but which take positions closer to ISIS, in shaping Hamas’s violence on October 7 [42].

Competing Interest:

The authors of this research declare no competing interest regarding this study.

References

Prowant, Max. (2024). “Why the Hamas-ISIS Comparison is Appropriate.” Providence. View

Federman, Josepf (Nov. 29, 2023). “Israel likens Hamas to the Islamic State group. But the comparison misses the mark in key ways.” Associated Press. View

Maher, S. (2016). Salafi-Jihadism: The History of an Idea. New York: Penguin Books, 14. View

Strindberg, A. and M. Warn. (2011). Islamism: Religion, Radicalization, and Resistance. Malden, MA: Polity and Sen, S. (2020). Decolonizing Palestine: Hamas between the Anticolonial and the Postcolonial. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. View

Al-Baghdadi, A.B. (2016). “Declaration of a Caliphate.” In Ideals and Ideologies: A Reader, 10th edition. T. Ball, R. Dagger, & D. O’Neill (eds). New York: Routledge, 576-577. View

Maher, 71.

Al-Zarqawi, A. M.(2020). “Letter to al-Qaeda Leadership.” In The ISIS Reader: Milestone Texts of the Islamic State Movement. H. Ingram, C. Whiteside, & C. Winter (eds). London: Hurst & Company, 40.

Levitt, M. and Y. Cohen. (2010). “Deterred but Determined: Salafi-Jihadi Groups in the Palestinian Arena.” Washington Institute for Near East Policy. View

Hamas. (2017). “A Document of General Principles & Policies.” View

Quoted in Solomon A.B. (2025). “Experts say Hamas and ISIS cooperating to fight their new common enemy: Egypt.” Jerusalem Post 17 Dec. 2015.

Hamas. (2009). “Charter of the Islamic Resistance Movement (Hamas) of Palestine.” In Princeton Readings in Islamist Thought. R. Euben and M. Q. Zaman (eds). Princeton: Princeton University Press, 377.

On the tacit acceptance of the 1967 borders and even borders as agreed upon in international negotiations see Hamas’s 2017 charter revision.

Naji, A.B. (2003). The Management of Savagery: The Most Critical State Through Which the Umma Will Pass. Trans. W. MCants, 10.

See Mello, B. (2018). “The Islamic State: Violence and Ideology in a Post-Colonial Revolutionary Regime.” International Political Sociology. 12: 139-155. View

Maher, 32.

Al-Zarqawi, A.M. (2004). “Al-Zarqaki Message Defends Executions, Calls for Jihad”. View

See, Litvak, M. (2010). “’Martyrdom is Life’: Jihad and Martyrdom in the Ideology of Hamas.” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 33(8): 716-734.View

On the internal discussions that lead Hamas to suspend attacks on Israel for fear of losing popular support during the early stages of the Oslo peace process see: Mishal, S. and A. Sela.(2000). The Palestinian Hamas: Violence, Vision, and Coexistence. New York: Columbia University Press.

See, O’Hearn, M. (2016). “Seeing is believing: early war photography.” View

See Friis, S.M. (2015). “Beyond Anything We Have Ever Seen: Beheading Videos and the Visibility of Violence in the War against ISIS.” International Affairs, 91(4): 725-746. View

Whiteside, C. (2016). “Lighting the Path: The Evolution of the Islamic State Media Enterprise (2003-2016). International Centre for Counter Terrorism – The Hague. View

Dauber, C. and M. Robinson. (2015). “ISIS and the Hollywood Visual Style.” Jihadology. View

Nanninga, P. (2017). “Meanings of Savagery.” In The Cambridge Companion to Religion and Terrorism. J. Lewis (ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. View

Winter, C. (2019). “Researching Jihadist Propaganda: Access, Interpretation, & Trauma.” RESOLVE Network.

Mello, 141.

Nanninga, 177.

Activists and Palestinian resistance supporters often use the word “genocide” when referring to Israeli policy and military action.

Hamas Media Center.(2023). “Our Narrative . . . Operation al Aqsa Flood.”View

Ibid.

It is important to note that this later effort to underplay the significance of civilian targeting runs somewhat counter to declarations made by Mohammed Dief, head of Hamas’s military wing, immediately after the October 7 attack. Deif’s statement suggests that the attack responded to Israeli violence in the West Bank, violence at the site of the al Aqsa Mosque, and Arab normalization with Israel, and demonstrated the capacity of Palestinians militants even calling for others to join in the armed struggle.

Bin Laden, 0. (2007). “Why we are Fighting You” in The al Qaeda Reader. R. Ibrahim (ed.). New York: Broadway Books, 200.

Hamas Media Center.

This message appears in Arabic and English in text during the video's introductory scene. View

Nanninga, 174.

Gillis, C. (2020). “Brutality and Spectacle: Beheading in the age of its Technological Reproducibility.” The Baffler, 51. View

Ibid.

Euben, R.L. (2017). “Spectacles of Sovereignty in Digital Times: ISIS Executions, Visual Rhetoric and Sovereign Power.” Perspectives on Politics, 15(4): 1017.

Hamas Media Center.

Euben, 1016.

Love, N. (2011). “Introduction: Ideology and Democracy.” In Dogmas & Dreams: A Reader in Modern Political Ideologies. N. Love (ed). Washington: CQ Press, 8. View

Feeden, M. (2006). “Ideology and Political Theory.” Journal of Political Ideologies, 11(1), 10. View

The emergence of Salafist groups within Gaza presented a challenge to Hamas in ways, for example, that might have contributed to forms of competitive behavior contributing to the October 7 attack. Clarke, C. (2017). “How Salafism’s Rise Threatens Gaza: What it Means for Hamas and Israel.” Foreign Affairs. View