Journal of Political Science and Public Opinion Volume 3 (2025), Article ID: JPSPO-124

https://doi.org/10.33790/jpspo1100124Review Article

The Capacity of the Public: Citizen Participation and the Crisis of Democracy

Sarah M. Smith1* and Treven F. Sekula2

1Associate Professor, Department of Political Science and Criminal Justice, California State University, Chico, California,United States.

2Norman Adrian Wiggins School of Law, Campbell University, Raleigh, North Carolina, United States.

Corresponding Author: Sarah M. Smith, Associate Professor, Department of Political Science and Criminal Justice, California State University, Chico, California, United States.

Received date: 25th March, 2025

Accepted date: 16th June, 2025

Published date: 19th June, 2025

Citation: Smith, S. M., & Sekula, T. F., (2025). The Capacity of the Public: Citizen Participation and the Crisis of Democracy. J Poli Sci Publi Opin, 3(1): 124.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Abstract

In this essay we examine “public opinion”—a core concept of democratic theory—in the United States. We explore a foundational question in democratic deliberation and public opinion scholarship: what is the capacity of the public? We first briefly review the meaning, history and theories of public opinion. We then address public opinion in the modern U.S. sociopolitical context, assessing the “crisis of democracy” vis-à-vis the public, highlighting the impact of rapid changes in media and subsequent changes in public spaces and interaction. We address key scholars’ contributions to the debate surrounding the capacity of the public, how these views lead to endorsement of different conceptions of democracy, and how contemporary empirical studies have contributed to the debate. A general decline in American civic participation notwithstanding, we argue that a fairly robust capacity exists for individual members of the general public to formulate sophisticated opinions and engage in democratic deliberation, collective action, and political participation. We offer some suggestions for increasing opportunities for public opinion formation, citizen deliberation and political participation in the current, polarized U.S. political environment. Expanding access to voting, increasing funding for civics education and forums fostering deliberative democracy, and advancing a media reform program to ensure the independence of news outlets are central to this effort.

The Meaning and History of Public Opinion

Where public opinion connects to voter choice, popular consent confers legitimacy to the controlling regime, and theoretically to the government itself [1]. Study of public opinion helps explain collective behavior, though a public is distinct from masses or crowds. A public is a “group of people (a) who are confronted by an issue; (b) who are divided in the ideas as to how to meet the issue; and (c) who engage in discussion over the issue.” Public opinion is expressed in the public sphere through social interaction, specifically communication. The public sphere has existed throughout history in different forms from the Symposia of Athens, the banquets of Rome, and the longhouses of the Iroquois to coffeehouses, barbershops, and Facebook.

In The Model Case of British Development, Habermas discusses how coffeehouses provided a place for socialization and debate, hence belief formation, political socialization, and democratic deliberation [2]. Habermas develops “how the classical bourgeois public sphere was constituted around rational critical argument, in which the merits of arguments and not the identities of arguers” were debated [3]. A contemporary definition of the public sphere is the “third place.” Oldenburg [4] argues that a place for socialization outside of the home and work is essential for society and individuals. Third places fulfill psychological and social human needs, they are “a great good place to congregate, commiserate, celebrate, dream, and grow together” [4]. They act as engines of democracy, driving political and social change, and have served as the physical location of the public sphere. They expand the orbits of the individual in society, providing space for the development of social capital in communities and engagement in complex socialization with implications for public opinion, political participation, and civic engagement. Oldenburg, examining the public sphere through the past several centuries, finds public and social spheres vary in their setting—such as different historical, social, and technological conditions—which influences how effective these spheres facilitate social benefits including democratic deliberation, civic engagement, and community building.

In the following, we argue that more opportunities for political socialization and deliberation should be provided in the United States in order to develop a more empowered citizenry, aligning with conceptions of the public as capable of impacting policy over those proposing a more limited role of the public and a top-down leadership model. We first review major theoretical debates regarding public opinion and address the role of public opinion in the political environment in the U.S. Assessing the crisis of democracy, we then identify methods for combating the crisis, engendering a more informed and participatory public and a more democratic society.

Theories of Public Opinion

Perhaps the most prominent debate regarding the role of public opinion in democracies is that between scholars Walter Lippmann and John Dewey. Lippmann’s foundational work, Public Opinion, opined for rule by the power elite and the Fourth Estate, reflecting a limited view of the capacity of the public in favor of ivory tower elitism of the academies, elevating the news media of the time, newspapers, to a pedestal [5]. Lippmann raised legitimate questions about the public’s knowledge base and its expertise on specific policies. Yet his rhetoric assumed political and media elites were virtuous and should be appealed to for guidance, conceiving of a definition of public opinion as a reflection of elite and media influence. On the other hand, Dewey’s The Public and Its Problems argues that expert administrators, technocrats, and the rise of the bureaucratic state in the late 19C and early 20C mystified the political system and distanced a capable public from participation in democratic self-government. Dewey rebuts Lippmann’s argument for a more inclusive definition of public opinion as an aggregation of individual opinions.

Dewey and Lippmann’s divergent definitions of public opinion lead to different conceptions of democracy. Where Lippmann advocates top-down rule by the power elite, Dewey appeals to bottom-up direct democracy by democratic deliberation. Dewey contended that political democracy at the time “calls for adverse criticism in abundance” [6]. Dewey advocates for enacting change to correct political structures, such as the Electoral College, that obfuscated the public from the political process and effective participation. Where Lippmann observed the public as simpletons, Dewey argued that individual members of the general public were capable though they were eclipsed from participatory democracy by cronyism, corporate interest, and political exclusion. Transforming public opinion into electoral behavior requires the production of social and political capital, which can be created through thriving public discourse, characterized by social participation, civic engagement, and democratic deliberation in communities. Dewey argued, “The essential need . . . is the improvement of the methods and conditions of debate, discussion and persuasion. That is the problem of the public” [6]. Dewey’s deliberative conception of democracy provides for a more empowered public citizen.

Public Opinion in the U.S. Since 1950

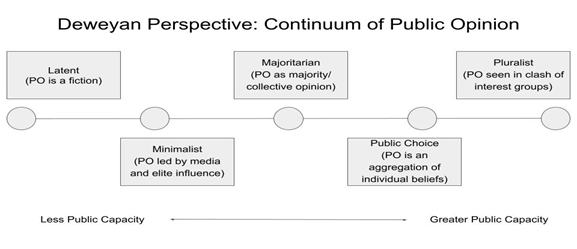

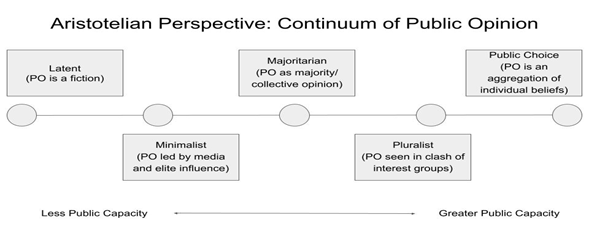

While not every member of the public can be an expert on every given policy topic or be fully informed about every official and candidate for office, a consensus of academic scholarship on public opinion since 1950 has placed the capacity of the public in the stewardship of American democracy. The main divergence in thought on public opinion since this time is that regarding the conceptualization of collective action networks and organizations as depicted in the original infographic below, identifying the two dueling conceptions of categories of public opinion as defined by Glynn et al. [7].

Although limits exist on the influence and capacity of the public, contemporary experimentation has generated empirical research that refutes more pessimistic claims about the citizenry’s ability to make sound judgments [8-11]. While some detractors say, “to hell with public opinion. We should lead not follow” [12], this nihilistic definition of public opinion as a fiction leads to an authoritarian conception of democracy. Within the context of American democracy, dismissals of public opinion are fraught with appeals for strong national leadership, an “energetic” administration, and stability of government. However, such a conception fails to safeguard against demagoguery by overestimating the virtue of political leaders. Should a leader without Machiavellian virtues rise to power, American democracy provides few checks against the executive privilege.

The potential dangers posed by such a conception are elucidated in the No Kings Act (2024) in response to Donald Trump’s success in beseeching the Supreme Court for immunity from crimes, particularly those associated with the January 6 insurrection at the United States capitol in 2021. Trump’s strategy to expand his power and limit efforts to hold him accountable given his anticipated return to the Presidency in 2024 paid off. The Supreme Court decision in the case allows Trump vast, unchecked power, stating that “the President is absolutely immune from criminal prosecution for conduct within his exclusive sphere of constitutional authority” and entitled him to a “presumptive immunity from all prosecution for his official acts” (No Kings Act, 2024, p. 3-4). While many of Trump’s initiatives have become immediately mired in legal challenges, reversals by the Trump administration of policies previously supported by both parties have given rival powers such as Russia and China more influence and put into question the security of the United States and its stance on promoting democracy [13-17].

The importance of expert opinion in specific areas of public policy, specifically foreign policy, constitute a focal point of debate surrounding definitions of public opinion. Empirical studies refute the gross simplification that Americans are too ill-informed to form rational opinions of matters of foreign policy and suggest that American public opinion on the topic is neither volatile nor capricious [18,19]. However, Page and Shapiro [19] concede that the public is susceptible to opinion manipulation, particularly regarding foreign affairs. Yet they demonstrate through multiple examples that the public opines relatively independently of elite persuasion, reacting in a rational manner to world events. Their “central arguments have to do with the capacity of the public to form rational opinions, given the information available” [19]. In other words, they illustrate that the public acts with bounded rationality and reflects consistency in ideology by examining a number of policy preferences deemed rational in light of public understanding of the world stage in real time.

Conceptualizing public opinion as an aggregation of individual opinions and providing the framework for the formation of those opinions, attitudes, and beliefs, Zaller [20] encapsulates the intersection of public opinion and political socialization in four points. Citizens vary in their attention and exposure to political information and arguments in the media, and they react critically to these arguments only to the extent that they are knowledgeable. They construct “opinion statements” as they are confronted with each issue rather than holding fixed attitudes on every issue, and they make these constructions using ideas that are most immediately salient to them [20].

Importantly, problems impacting citizen opinion and reasoning, such as polarization and framing, disappear or are significantly reduced in experimental tests when individuals are able to discuss and debate the task with others [21,22] and when they are induced to form an accurate opinion [23,24]. Deliberative democracy experiments that include opportunities to discuss in groups show ordinary people to be excellent reasoners [25-28]. In the latter sections of this article, we identify opportunities for more political socialization and opinion development and suggest limiting the capacity of privately-owned media to control information dissemination as ways to help address Zaller’s fourth point regarding opinion construction and Page and Shapiro’s concession regarding the potential for manipulation of public opinion. First, we discuss the development of the U.S. democratic system and how contemporary changes to the system inform the contexts in which opportunities to thoughtfully form opinions and deliberate with other citizens occur.

The Crisis of Democracy

The fits and starts of economic modernization since the Italian Renaissance have contributed to a steady ebb and flow of global democratization, from the Enlightenment to the Industrial Revolution and through the second millennium. However, the number of democracies worldwide have recently declined [29]. Noting a fair degree of volatility, in 2013 alone, five countries transitioned to democracy but nine became authoritarian regimes. Worrisome trends include a gradual erosion of freedom of expression and association in several countries, and Menchkova et al. [29] conclude that there is evidence of democratic backsliding since 2011 and of a global democratic recession. Using their methodology, for example, the U.S fell in the world rankings from 12th to 17th of liberal democracies in 2016 [29].

Some leading experts in public opinion research report that citizens and policymakers face a crisis of democracy related to certain aspects of modernism, particularly those associated with technology and mass media. Concerns have been building for some time, with social scientists arguing that Americans’ level of community engagement has been reducing in a number of realms, including political participation, such as low participation in elections, as illustrated in Putnam’s [30] Bowling Alone. Putnam suggests that the multiple markers of community disengagement are not only characteristic of democratic decline but of community collapse altogether. Differences in community involvement lead to consequences in vastly varied social phenomena, including violent crime, which is rarer in “high social-capital states” [30]. While Putnam identified the rise in television watching as the main cause of reductions in community engagement during the late 1990s, the ubiquitous nature of cell phones and the accompanying move to electronic communication as a replacement for traditional forms of political interaction is now a cause for concern given the role of the internet in spreading misinformation.

Social capitalists have demonstrated stark consequences of social and individual political participation for political tolerance [31]. As individuals engage in social political activities, their political tolerance is likely to increase [30-32]. However, not all political or all social participation increases political tolerance. Proposing that individuals who are involved in socially interactive environments will be exposed to a larger diversity of opinions and that political activity involving social interaction is more educative than non- social political behavior, Weber argues and finds that those who engage in political activities that involve social interaction have higher levels of political participation and tolerance, and political tolerance is not related to individual political participation. These results are independent of the influence of political tolerance on both social and individual participation, showing that tolerance is a consequence of social political participation rather than a cause [31]. While interaction in online political discussion may reflect increased engagement in political issues, which typically has a dampening effect on polarization, the reliance on digital media in the United States has been associated with increased polarization [33]. In times marked by low social political engagement or where that engagement is limited to online interaction, American citizens may be ceding control of the political conversation to foreign, corporate or party interests, and debates among these groups have become less civil and deliberative and more opportunistic and partisan, contributing to the “crisis of democracy.”

Technology & New Media

Internet, cell phones and social media are technological examples of intracohort change after the turn of the 21C that became ubiquitous utilities in the United States, and in many other countries. These inventions caused fundamental changes to the processes of political socialization and social participation. The dynamics of these types of spaces are both similar to and different from the generally unmediated interpersonal communication and commiseration that occurs in third spaces in the physical world. Online spaces provide the opportunity to connect with virtual crowds, allowing for social interaction and socialization. However, the Internet also allows people to segregate and isolate more than ever before. Racism, sexism, homophobia, and all other hateful ideologies are easily accessible, and social media provide space for ignorance and hate to breed [34]. Conspiracy theories are prevalent. Internet search algorithms predict and provide search results, leading to a confirmation bias. In addition, Big Data presents real-time mass monitoring of individual behavior from Internet, social media data and website metadata to transaction data, administrative data, and commercially available databases, presenting unique and unforeseen difficulties for media, public administrators, and the public [35].

While surveys and big data have great potential to complement one another to achieve positive changes in society, several concerns have been identified regarding the increased role of commercial and corporate media in democratic deliberation and public opinion and the use of social media to manipulate public opinion, elections and disrupt democracy [36-41]. The role of Russian media interference in the 2016 election of Donald Trump and the United Kingdom’s Brexit referendum serve as examples of social media manipulation [36,41,42]. Regarding the U.S. election, a grand jury indicted thirteen Russian nationals and three Russian entities for crimes related to interfering in the 2016 presidential election, with the purpose of undermining the electoral system and securing the election of Donald Trump. They were charged with conspiracy to defraud the United States through intelligence gathering, identity theft and the operation of fake media accounts, which were used to promote Trump and disparage frontrunner Hillary Clinton [41]. According to the report on the investigation, the Russian government engaged in “information warfare,” interfering with the election “in sweeping and systematic fashion” [43]. However, with the subsequent election of Donald Trump, the Justice Department dropped the prosecution a few weeks before the case was to go to trial, and the British Parliament’s Intelligence and Security Committee reported it was unable to determine if Russia influenced the Brexit referendum through a heavily redacted and significantly delayed report [44]. Nevertheless, the results of a social media study using the Twitter Streaming Application Interface found that effects of social bots’ tweet activity may have been large enough to affect the outcomes of both the Brexit vote and the 2016 United States election [45]. Uncontrolled corporate media monopolies can lead to dis-and mis- information in pursuit of political or financial gain by those who control them as well as a reduction in the diversity of opinions and policy options communicated via mass media. Those in control of media outlets have purposefully and grossly misinformed the public regarding political issues, including photoshopping images of Seattle’s autonomous zone, purposely mislabeling photographs of Minnesota as depicting Seattle, and lying about vote-rigging [46-49].

Overall, the pivot from print news media to online media may have exacerbated citizens’ ability to distinguish credible information from fake news. For example, the results of a study evaluating the ability of students, including Stanford undergraduates, to discern credible online information from biased or fake news, were called “bleak,” and “a threat to democracy” by the authors [50]. Those who are more socially isolated, particularly those in less diverse areas, are particularly vulnerable to being led astray by misinformation [51]. Though the internet has also been used to advocate for democracy and resist autocratic control [52], it appears that the narrowing of socialization to more online interaction in the United States is associated with less sophisticated and more partisan political discussion [9,33] and low-credibility content supported by social bots rather than real people [38]. In order to fully address the role of media in public opinion and citizen engagement in democracies, a deeper consideration of the impact of media on political socialization processes is necessary.

Sources of Public Opinion & the Role of Media

Two characteristics distinguish political socialization processes: (1) childhood learning predominately influences the formation of individual political outlooks; and (2) socialization continues throughout life and its effect is cumulative, meaning “prior attitudes are a screen through which new information is filtered” [53]. Primary socialization occurs through interaction with the family, school, and church, particularly early in life; these are considered the main groups in which political socialization occurs. However, if there is a breakdown in primary socialization processes, secondary socializing sources such as the media may take on more primary roles in shaping beliefs, attitudes and behaviors [54]. Secondary socializing agents include the peer environment, cultural and political leaders, and major events as well as interest groups, traditional news media, and elites. Some secondary socialization sources may be relevant to the development of individual opinion by contributing to belief formation as frames of reference [53]. While once typically considered a secondary socializing agent, social and technological changes in American life and the impact of media on adolescents warrant reconsideration of the media in primary socialization theory [54,55].

According to Oetting et al. [55], although media can have direct effects, media efforts to change behavior or habits are typically successful when they are supportive of already-established norms and enhance transmission of those norms through primary socialization sources. Selection, selective perception and exposure norming processes that occur through primary socialization can enhance media effects. Studies suggest that media messaging should be more effective when it taps into and enhances or extends norm and belief schemas that have already been formed through primary socialization. Second, media should have greater impacts when they can infiltrate primary socialization processes such as through family interactions, for example, watching “family-friendly” television programming prescribing gender norms [56]. Third, given exposure norming processes, media may be more effective when they are strategically placed—on particular websites and television channels, in particular magazines—in order to gain access to target audiences [56].

Given the increase in the amount and types of media accessible to the public and potential breakdowns in political discourse through civic participation and primary socialization routes, media may have a much larger impact on public opinion than in the past. In fact, McChesney [57] argues that the media, once considered a dependent variable in political theory, affected by public opinion and political elites, is now a major player in the control over the political and cultural landscape. Studies have found strong links, for example, between online media and increasing polarization. However, much of the empirical findings do not align with traditional theories of communication and public opinion [33]. Below, we discuss the crisis of democracy, how digital engagement may lead to polarization effects somewhat unique to the U.S., and the role of deliberation in democratic political participation. We then offer a discussion followed by policy suggestions including the importance of independent media and deliberative processes.

Polarized Party Politics

The roots of today’s intensely polarized party politics in the United States lie primarily in the fierce competition for the control of Congress during the 1980 election [58,59]. Klein observes that competitive federal elections and the absence of sustained party control have not only disincentivized bipartisanship in the bicameral legislature, but incentivized gridlock and obstructionism by the minority party [60]. The plausibility of regaining the majority of either or both houses of the Congress for a lawmaker’s party supplants the option to compromise as the choice in his or her self interest because the incentive of achieving bipartisan legislation is outweighed by the costs of potential policy concessions. This is especially the case when a legislative victory for the majority party may adversely affect public opinion of the minority lawmaker’s party and of the lawmaker personally and impact their possibility of reelection. Such zero-sum brands of politics engender “winner takes all” political mentalities and strategies and a significant increase in negative campaigning, which have contributed to “a marked decline in civility and argumentative complexity” [9,61]. In a vicious cycle, “uncivil behavior by elites and pathological mass communication reinforce each other” [9]:

Declining civility in interactions among elected representatives decreases citizens’ trust in democratic institutions. The more polarized (and uncivil) that political environments get, the less citizens listen to the content of messages and the more they follow partisan cues or simply drop out of participating. Declining complexity in arguments means a growing mismatch between the simple solutions offered by political leaders and real complex problems [9].

Polarization has thus not only stifled deliberation within and between governing institutions, but has also hampered deliberative conditions in the national public discourse. The tremendous increase in negative campaigning as well as the media’s penchant for recycling negative campaign rhetoric reinforces people’s suspicions about the other side rather than focusing on the quality of information and encouraging civil debate [61]. Additionally, in online political discussion, the distrust that groups harbor towards digital media aligned with the opposing party facilitates a “sorting” process whereby people become increasingly polarized [33]. Rather than online exposure to media challenging one’s worldviews, resulting in a moderating effect on people, the partisan alignment of online literature is associated with increased polarization. Typically, sorting processes take place locally in geographical spaces or social networks, leading to local alignment of issues, but diversity between regions leads to these alignments cancelling each other out. The cultural diversity between areas typically leads to more cross-cutting incentives, resulting in relatively high social cohesion. Törnberg [33] argues that, instead of cohesion, the increase in consumption of digital media dampens the counterforce and the geographical differences no longer counterbalance partisanship. He argues that this national level partisanship is particularly harmful in places like the United States, where the constitution is founded upon the existence of this counterbalancing:

The US House and Senate were intended to represent not two parties but the nation’s districts and states, allowing regional interests to moderate partisan excesses…such federalism can effectively provide a source for cross-cutting cleavages, thus functioning as a safeguard and counterweight to the national government. However, affective polarization can undermine this system as loyalties to parties become stronger than to the state or region (p. 8).

Increased polarization and zero-sum politics also combine with other aspects of the “modern” moment to contribute to a “citizenship deficit” in the U.S., resulting in the “1) increasing professionalization of civic participation in civil society organizations; and 2) greater individualization of collective action of citizens” [62]. In modern politics, organizations have acknowledged the greater “efficiency” and effectiveness of lobbying and employing experienced technocrats, as well as the role of money, in achieving political goals. Citizen participation has become more individualistic and is more often characterized by financial contributions and consumer boycotts rather than large group action based on in-person deliberation [62]. In addition, some argue that campaigning through television transformed the U.S. from a representative democracy to an “audience democracy” in which politicians are merely media personalities that citizens choose from, limiting meaningful democratic participation among citizens [63].

The election of President Donald Trump in 2016 signaled a peak in polarization in the U.S. [64]. Rather than harnessing the possibilities of populist governance through deliberative democracy, as Peters and Pierre's typology [65] suggests is potentially possible and positive, we argue that the Trump administration’s tactical, partisan politicization of the power of appointment of staff and judges, and its neutralization of the vast depth of norms, knowledge, and oversight of the bureaucracy resulted in an administration more concerned about “rhetoric and possibly winning elections” than giving thought to governance and public administration, as the authors suggest generally characterizes recent populist governments. Dodge [62] notes that it is not clear what is the best path to address the modern tensions between democracy and efficiency to affect more citizen engagement. Below, we review deliberation practices, one area where we believe attention should be focused in an effort to address issues of citizen participation and the capacity of the public in modern U.S. society.

Democratic Deliberation and Deliberative Polling

Deliberative experiments show that information accumulation is increased through participation in democratic deliberation, specifically deliberative polling [66]. Deliberative polls are “the strongest in representativeness, very strong on outcome measurement, and equal to any other in balanced materials, policy links, and quality of space for reflection” (p. 55). They are particularly effective in providing opportunity for discussion with representative groups holding differing opinions and offer a safe space for deliberation, facilitated by moderators. This design avoids social pressure to conform yet also leads to fewer participants taking extreme positions, likely also due to the provision of balanced reference information on the “pro” and “con” positions of an issue. For example, deliberative polls have produced more informed preferences on a wide range of topics and have been successful in promoting cooperation even with groups with a history of violent conflict, such as in the case of a deliberative poll in 2007 in Northern Ireland with Protestants and Catholics regarding education. After only one day of deliberation, community perceptions and policy attitudes changed drastically, with a 16% increase in believing the other group is “open to reason” for both Protestants and Catholics, significant reductions in zero-sum mentalities, and overall knowledge index increases of thirty points, with some questions garnering increases of more than fifty points [27].

Mansbridge argues that deliberative polls may be particularly helpful in providing considered public opinion on issues before primaries or referenda or on legislative action requiring input from the citizenry; the ability to refer back to debate and deliberation by citizens on difficult topics may help provide cover for politicians hoping to address such issues in productive, yet politically unpopular ways, such as through tax increases. Additionally, deliberative polls can significantly reduce the effects of selective attention, processes where citizens subconsciously or consciously pay attention, give more credence to, or choose to consume content supportive of their already held beliefs, processes leading to confirmation bias effects. Studies also find that deliberation helps overcome bias, enabling accurate reasoning [67]. In addition, studies find that citizens’ juries provide a more active form of citizen engagement, requiring respectful, thoughtful deliberation. Applying affirmative measures or drafting a pre-jury contract can minimize issues of unequal representation noted by Sanders [68], or biased selection of jurors by decisionmakers [69,70]. Similar in design to legal juries, citizens’ juries produce a decision or recommendations in the form of a report after analyzing and debating a policy issue, to which the government or agency sponsoring the policy change must respond. Fung [71] identifies several deliberative democracy forums, using the umbrella term “minipublics,” as effective in several different features of evaluation, such as: quantity and quality of engagement; minimization of participation bias; respectful and democratic socialization; increased accountability of officials; the justice achieved and effectiveness of the policy action taken; and civic mobilization of other citizens. Some minipublics highlighted as successful include deliberative polling, town halls such as America Speaks Citizen Summits, the bottom-up budget decision-making Participatory Budget in Porte Alegre, Brazil [71], the Citizen’s Initiative Review in Oregon, and the British Columbia Citizen’s Assembly [72].

As a way to help ensure highly engaged, involved and educated voters, findings in Stucki, Pleger and Sager’s [73] study of a split ballot survey recommend deliberative democratic exercises that offer pro and con opinions, as Mansbridge suggested, including evaluation results surrounding the opinions, and that require a vote. They argue that such techniques to inform and engage voters can quell critiques levied by Lippmann [5] of the public as uninformed and prone to making post-factual decisions. Similarly, Cohen [69] recommends that deliberative democracy must involve equals who reason together and come to a decision with a vote, as reasonable people will disagree on the best method for resolving complex problems in a pluralistic society.

On the balance, the findings suggest the utility in fostering minipublics and other similar deliberative forums that provide balanced and unbiased information on salient issues to the public [72,74]. The literature also suggests that successful outcomes depend on the specific type of deliberative forum and processes and their intended purposes as well as certain principles that lead to successful outcomes [9,71].

Discussion and Conclusion

The expansion of the electorate, and most recently the transformation of the media with the Internet, defines, in part, the historical and socio-political conditions of modern times. These changes coincide with the stark changes in citizen participation, and the near-collapse of American community. Recent public opinion scholarship analyzes the individual rather than minority factions or the power elite. Involvement in deliberative political processes empowers the individual to govern in an informed and reasonable fashion based on the available information at the time. Despite the many limitations, we argue that a fairly robust capacity exists for individual members of the general public to formulate sophisticated opinions and engage in democratic deliberation, collective action, and political participation.

While Druckman [61] asserts that trying to discern what constitutes “quality opinion” is a false start, and Straßheim [75] argues that behavioral public policy’s project of “de-biasing democracy has its own biases” (p. 122), Druckman’s suggestions for increasing the public’s political and policy issue competence implicitly address the capacity of the public. He argues that we should focus on the process of opinion formation, specifically focusing on what motivates the formation of an opinion. Motivation to form an informed and accurate opinion is higher regarding issues that inform presidential evaluations [76]. This is particularly the case for: those issues that people believe impact their self-interests [77]; when they will be directly affected by a policy [78]; or when they experience some pressure from social groups to be knowledgeable, for example, in an instance where the person will need to be prepared to discuss or debate a policy with others [24,79]. Such interaction, encouraged in deliberative settings, can improve individuals’ objectivity in the anticipation of having to justify the opinion. Deliberative processes can overcome partisan group influence effects on opinion, as individuals in American society are primarily part of groups with non-political influences.

Even taking into consideration critiques of deliberation [80], Druckman’s [61] argument regarding the role of anticipation in motivation to form an accurate opinion is well taken, outside of the relatively large body of support for the beneficial outcomes of deliberation [69,72,74,81]. Whether or not deliberation is actually required, the opportunity to and expectation that citizens will deliberate may very well spur them to better prepare for political participation and to participate more frequently, as well as more deeply and at higher levels [69]. Increasing opportunities for citizen deliberation may provide more opportunities for meaningful dialogue on policy issues, prevent extremist posturing among the public and reduce the effect of media misinformation and bias through reduction of the impacts of selective attention. Druckman [61] suggests that some relatively simple electoral reforms, such as same-day voter registration, allowing voting on holidays and weekends and other similar strategies will improve citizen access and increase competition among political communicators, motivating communicators to provide better and more information to prove that their rhetoric rings truer than their competitor’s.

While the Trump administration reflected a decline in democracy in the U.S., a trend seen across several countries, as well as increases in authoritarian political behavior and hate crime [82,83], Trump’s nationalist populism served as an impetus for increased political participation. The 2020 U.S. presidential election produced record turnout, the highest participation since 1912 [84,85]. However, following the unfounded claims of voter fraud in the 2016 and 2020 elections [86-89], questions regarding election security and Republican advocacy have resulted in “an avalanche of legislation” limiting political participation, with several states and counties enacting a wide range of restrictions on voting and representation, efforts an expert on voting and elections called “dangerously antidemocratic” [89]. While gerrymandering has been used by both major U.S. parties to gain political advantage, we argue that voter restrictions such as those passed in Georgia will exacerbate the impacts of voter suppression and inequalities in the U.S., limiting access to minorities and young people [89-91], and they will also have little impact on voter fraud, which was not systemic, widespread or significant in either election [84,88,92]. Similarly, the more recent introduction of the SAVE Act threatens to exclude tens of millions of Americans, impacting most significantly voters of color, married women, and younger voters [93].

These antidemocratic actions limiting political engagement serve to exacerbate the conditions cited by Putnam as pushing the U.S. closer to community collapse. Dual income households are now the norm, with more people working two jobs than in earlier decades when voter participation and community engagement were higher. Wage stagnation and increasing income inequality combined with the limited employee benefits characterizing new service and gig economies have contributed to increased public anxieties and may drive down citizen political participation, particularly among the poor [64,94,95]. The impacts of Covid-19 brought these issues to a fever pitch, spurring high unemployment, particularly among women, pushing them closer to the poverty line [96]. Some Americans picked up new jobs and worked more hours or had to take unpaid leave for various reasons, including attending to sick family members or their changing home economics, yet others who were laid off re-evaluated their careers and priorities, spurring a movement demanding higher wages and better benefits [97,98]. Many of those in the latter camp also became more politically engaged in a variety of ways, including collective action such as movements advocating for a “living wage” or the development of universal basic income programs, or the “democratization” of financial markets [99,100], while the pandemic also resulted in increased isolation and reliance on social media, spurring dissemination of misinformation [38].

As the new administration works to limit political participation through voter suppression [93,101], this a pivotal moment for increasing the community engagement that was seen in some arenas during the pandemic and for addressing the vast inequalities in opportunities to participate that remain problematic. We first implore voters to assert their rights to access the polls amidst threats to circumscribe these rights. We further suggest same-day voter registration, the adoption of a national election day as well as allowing absentee voting and voting on holidays and weekends so that full-time working parents and those who work more than one job can participate in elections without risking their livelihoods should a “tri-epidemic” emerge or another pandemic arise. We also recommend increased use of deliberative polls and other opportunities for meaningful citizen dialogue to inform legislation and political referenda, particularly for politically unpopular issues, such as tax increases [66,71,72]. Forums and bodies such as citizens’ juries and “minipublics” like town halls may increase the capacity of the public by involving them in democratic deliberation and decision making about policies that will impact them [70,71]. We also suggest earlier opportunities for education in citizenship and government in order to encourage deliberation at younger ages that will continue throughout individuals’ lives and allow for more diversity of political socialization [102].

Lastly, we suggest mitigation of partisan and profit-motivated influence in mass media to ensure a pivot to sufficiently “independent” media outlets, as well as judicial remedy where media are exploitatively used to promote misinformation for political or financial gain, by statutory authority prescribed by comprehensive legislation for the regulation of new and traditional media [69,71]. McChesney [57] argues that an entire program and strategic plan for reforming and creating a more democratic media are necessary to a working democracy in the U.S. Such a comprehensive legislative package might begin by addressing the use of media in promoting legislation limiting voting rights as a first step [89]. With more robust engagement and increased citizen participation in the political process, only candidates who do not truly support and promote the interests of their constituents would be concerned about those same constituents learning about the true impact of policymakers’ decisions.

Competing Interest:

The authors of this research declare no competing interest regarding this study.

References

Powlick, P. J. (1995). The sources of public opinion for American foreign policy officials. International Studies Quarterly, 39(4), 427-451. View

Habermas, J. (1989). The structural transformation of the public sphere: An inquiry into a category of bourgeois society. MIT Press. View

Calhoun, C. (1992). Habermas and the Public Sphere. MIT Press. View

Oldenburg, R. (1999). The Great Good Place: Cafés, coffee shops, bookstores, bars, hair salons, and other hangouts at the heart of community. Publishers Group West. View

Lippmann, W. (1922). Public Opinion. Harvard University Press. View

Dewey, J. (1927). The Public and Its Problems. Holt Publishers. View

Glynn, C. J., Herbst, S., Lindeman, M., O’Keefe, G. O., & Shapiro, R. Y. (2015). Public Opinion. 3rd Edition. Routledge. View

Chambers, S. (2018). Human life is group life: Deliberative democracy for realists. Critical Review, 30(1-2), 36-48. View

Dryzek, J. S., Bächtiger, A., Chambers, S., Cohen, J., Druckman, J. N., Felicetti, A., Riskin, J. S. Farrell, D. M., Fung, A., Gutmann, A., Landemore, H., Mansbridge, J., Marien, S., Neblo, M. A., Niemeyer, S., Setälä, M., Slothuus, R., Suiter, J., Thompson, D., & Warren, M. E. (2019). The crisis of democracy and the science of deliberation. Science, 363(6342), 1144-1146. View

Curato, N., Vrydagh, J. & Bächtiger, A. (2020). Democracy without Shortcuts: Introduction to the Special Issue. Journal of Deliberative Democracy, 16(2), 1–9. View

Li, J. & Wagner, M. W. (2020). The value of not knowing: Partisan cue-taking and belief updating of the uninformed, the ambiguous, and the misinformed. Journal of Communication, 70(5), 646-669. View

Cohen, B. (1973). The Public’s Impact on Foreign Policy. Little, Brown and Company. View

Zakaria, F. (2025, March 7). Trump upending world order will cost America deeply. The Washington Post. View

De Luce, D. (2025, February 26). ‘China is the real winner’: Trump’s reversal in Ukraine aids Beijing, Western officials say. NBC News. View

Better World Campaign (2025, February 28) U.S. Foreign Assistance Developments. View

Mateo, L.R. (2020). The changing nature and architecture of U.S. democracy assistance. Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo 63(1). View

Azpuru, D., Finkel, S.E., Pérez-Liñán A., and Seligson, M.A. (2008). Trends in democracy assistance: What has the United States been doing? Johns Hopkins University Press, 19(2), 150 159. View

Kertzer, J. D., & Zeitzoff, T. (2017). A bottom-up theory of public opinion about foreign policy. American Journal of Political Science, 61(3), 543-558. View

Page, B. I., & Shapiro, R. Y. (1992). The Rational Public: Fifty Years of Trends in Americans’ Policy Preferences. University of Chicago Press. View

Zaller, J. R. (1992). The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion. Cambridge University Press. View

Strandberg, K., Himmelroos, S. & Grönlund, K. (2017). Do discussions in like- minded groups necessarily lead to more extreme opinion? Deliberative democracy and group polarization. International Political Science Review, 40(1), 41-57. View

Druckman, J. N. & Nelson, K. R. (2003). Framing and deliberation: How citizens’ conversations limit elite influence. American Journal of Political Science, 47(3), 729-745. View

Bolsen, T., Druckman, J. N. & Cook, F. L. (2014). The influence of partisan motivated reasoning on public opinion. Political Behavior, 36(2), 235-262. View

Sinclair, B. (2012). The social citizen. The University of Chicago Press.View

Clément, R. J. G., Krause, S., von Engelhardt, N., Faria, J. J., Krause, J. & Kurvers, R. H. J. M. (2013). Collective cognition in humans: Groups outperform their best members in a sentence reconstruction task.” PLOS ONE, 8(10): e77943. View

Warren, M. E., & Pearse, H. (2008). Designing deliberative democracy: The British Columbia’s Citizens’ Assembly. Cambridge University Press. View

Fishkin, J. C. (2009). When the people speak: Deliberative democracy and public consultation. Oxford University Press. View

Fishkin, J. C. (2018). Democracy when the people are thinking: Revitalizing our politics through public deliberation. Oxford University Press. View

Menchkova, V., Lurhrmann, A., & Lindberg, S. I. (2017). How much democratic backsliding? Journal of Democracy, 28(4), 162-169.View

Putnam, R. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon & Schuster. View

Weber, L. (2003). Rugged individuals and social butterflies: The consequences of social and individual political participation for political tolerance. The Social Science Journal, 40(2), 335–42. View

Conover, P.J. & Searing, D.D. (2005). Studying ‘everyday political talk’ in the deliberative system. Acta Politica, 3(4), 269-283. View

Törnberg, P. (2022). How media drive affective polarization through partisan sorting. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences – PNAS, 119(42): 1-11. View

Korvela, P. (2021). From utopia to dystopia: Will the internet save or destroy democracy?” Redescriptions: Political Thought, Conceptual History, and Feminist Theory, 24(1), 1-3. View

Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K. H., Seifert, C. M., Schwarz, N., & Cook, J. (2012). Misinformation and its correction: Continued Influence and successful debiasing. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 13(3), 106-131. View

Weng, Z. & Lin, A. (2022). Public opinion manipulation on social media: Social network analysis of Twitter bots during the Covid-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 19(24): 1-17. View

Eck, A., Cazar, A. L. C., Callegaro, M., & Biemer, P. (2019). Big Data meets survey science. Social Science Computer Review, 39(4), 484-488.View

Shao, C., Ciampaglia, G.L., Varol, O., Yang, K., Flammini, A., & Menczer, F. (2018). The spread of low-credibility content by social bots. Nature Communications, 9: 1-9. View

Callegaro, M., & Yang, Y. (2018). The role of surveys in the era of ‘Big Data. In D. L. Vannette & J. A. Krosnick (Eds.), Palgrave handbook of survey research (pp. 175–192). Springer International. View

Baker, R. (2017). Big data: A survey research perspective. In P. P. Biemer, E. D. de Leeuw, S. Eckman, B. Edwards, F. Kreuter, L. E. Lyberg, N. C. Tucker, & B. T. West. (Eds.), Total survey error in practice, (p.p. 47–70). Wiley. View

United States of America v. Internet Research Agency (2018). United States District Court for the District of Columbia. Case No 1:18-cr-00032. View

Bradshaw, S. & Howard, P.N. (2018). The global organization of social media disinformation campaigns. Journal of International Affairs, 71(15), 23-32. View

Mueller, R. S. (2019). Report on the investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election. U.S. Department of Justice. View

Dwyer, C. (2020, July 21). U.K. “actively avoided” investigating Russian interference, lawmakers Find. NPR. View

Gorodnichenko, Y., Pham, T. & Talavera, O. (2018). “Social media, sentiment, and public opinions: Evidence from #Brexit and #USElection.” (Report No. 24631). View

Brunner, J. (2020, June). Fox News runs digitally altered images in coverage of Seattle’s protests, Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone. The Seattle Times. View

Barr, J. (2020, December 21). Newsmax issues sweeping ‘clarification’ debunking its own coverage of election misinformation. Washington Post.

Levinson, M. (2021, May 1). Newsmax apologizes for false claims of vote-rigging by a Dominion employee over election claims. The New York Times. View

Bauder, D. Chase, R and Mulvihill, C. (2023, April 18). Fox, Dominion reach $787 million settlement over election claims. AP News. View

Wineburg, S., McGrew, S., Breakstone, J. & Ortega, T. (2016). Evaluating information: The cornerstone of civic online reasoning. Stanford Digital Repository. View

De Freitas, J, Falls, B. A., Haque, O. S., & Bursztain, H. J. (2013). Vulnerabilities to misinformation in online pharmaceutical marketing. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 106(5), 184-189. View

Pang, H. (2018). Is mobile app a new political discussion platform? An empirical study of the effect of WeChat use on college students’ political discussion and political efficacy. Public Library of Science (PLoS ONE), 13(8), 1-16. View

Patterson, T. E. (2019). We the People: An Introduction to American Government. McGraw-Hill Education. View

Kelly, K., & Donohew, L. (2009). Media and primary socialization theory. Substance Use and Misuse, 34(7), 1033-1045. View

Oetting, E. R., Donnermeyer, J. F., & Deffenbacher, J. L. (1998). Primary socialization theory: The influence of the community on drug use and deviance. Substance Use & Misuse, 33(8), 1629-1665. View

Perse, E. M. (2001). Media effects and society. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. View

McChesney, R. W. (2015). Rich Media, poor democracy: Communication politics in dubious times. The New Press. View

Lee, F. E. (2016). Insecure Majorities: Congress and the Perpetual Campaign. Chicago University Press. View

Larson, B. (2018). [Review of Insecure majorities: Congress and the perpetual campaign, F. E. Lee]. Party Politics, 25(1), pp. 89-90. View

Klein, E. (2020). Why We’re Polarized. Simon & Schuster. View

Druckman, J. N. (2014). Pathologies of studying public opinion, political communication, and democratic responsiveness. Political Communication, 31(3), 467-492. View

Dodge, J. (2013). Addressing democratic and citizenship deficits: Lessons from civil society? [Review of New participatory dimensions in civil society: Professionalization and individualized collective action, edited by J. W. van Deth & W. A. Maloney]. Public Administration Review, 73(1), pp. 203-206. View

Hardin, R. (2009). Deliberative democracy. In T. Christiano & J. Christman (Eds.), Contemporary debates in political philosophy (pp. 231-246). Wiley. View

West, D. M. (2019). Divided politics, divided nation: Hyperconflict in the Trump era. Brookings Institution Press. View

Peters, B. G., & Pierre, J. (2019). Populism and public administration: Confronting the administrative Administration & Society, 51(10), 1521-1545. View

Mansbridge, J. (2010). Deliberative polling as the gold standard. The Good Society, 19(1), 55-62. View

Bago, B., Rand, D. G., & Pennycock, G. (2020). Fake news, fast and slow: Deliberation reduces belief in false (but not true) news headlines. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 149(8), 1608-1613. View

Sanders, L. M. (1997). Against deliberation. Political Theory, 25(3), 347-376. View

Cohen, J. (2009). Reflections on deliberative democracy. In T. Christiano & J. Christman (Eds.), Contemporary debates in political philosophy (pp. 247-263). Wiley. View

Smith, G., & Wales, C (2000). Citizens’ juries and deliberative democracy. Political Studies, 48(1), 51-65. View

Fung, A. (2003). Recipes for public spheres: Eight institutional design choices and their consequences. The Journal of Political Philosophy, 11(3), 338-367. View

Warren, M. E., & Gastil, J. (2015). Can deliberative minipublics address the cognitive challenges of democratic citizenship? The Journal of Politics, 77(2), 562-574. View

Stucki, I., Pleger, L. E., & Sager, F. (2018). The making of the informed voter: A split-ballot survey on the use of scientific evidence in direct-democratic campaigns. Swiss political science review, 24(2),115-139. View

Weeks, E. C. (2000). The practice of deliberative democracy: Results from four large-scale trials. Public Administration Review, 60(4), 360-372. View

Straßheim, H. (2020). The rise and spread of behavioral public policy: An opportunity for critical research and self-reflection. International Review of Public Policy, 2(1), 115-128. View

Krosnick, J. A. (1998). The role of attitude importance in social evaluation: A study of policy preferences, presidential candidate evaluations, and voting behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 55(2), 196-210. View

Boninger, D. S., Krosnick, J. A., & Berent, M. K. (1995). Origins of attitude importance: Self-interest, social identification and value relevance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(1), 61-80. View

Campbell, A. L. (2002). Self-interest, social security, and the distinctive participation patterns of senior citizens. American Political Science Review, 96(3), 565-574. View

Gerber, A. S., Green, D. P., & Larimer, C. W. (2008). Social pressure and voter turnout: Evidence from a large-scale field experiment. American Political Science Review, 102(1), 33-48. View

O’Malley, E., Farrell, D. M., & Suiter, J. (2020). Does talking matter? A quasi-experiment assessing the impact of deliberation and information of opinion change. International Political Science Review, 41(3), 321-334. View

Freeman, S. (2000). Deliberative democracy: A sympathetic comment. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 29(4), 371-418. View

Abramowitz, M. J., & Repucci, S. (2018). Democracy beleaguered. Journal of Democracy, 29(2), 128-142. View

Edwards, G., & Rushin, S. (2018). The effect of President Trump’s election on hate crimes. Social Science Research Network, 652. View

Persily, N., & Stewart III, C. (2012). The miracle and tragedy of the 2020 U.S. election. Journal of Democracy, 32 (2), 159-178. View

McDonald, M. P. (2020). National general election VEP turnout rates, 1789-present. U.S. Election Project. View

Canon, D. T., & Sherman, O. (2021). Debunking the “Big Lie”: Election administration in the 2020 presidential election. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 51(3), 546-581. View

Corasiniti, N., & Epstein, R. J. (2021, March 27). In Georgia, G.O.P. Fires First Shots of Voting Battle. The New York Times. View

Cottrell, D., Herron, M. C., & Westwood, S. J. (2018). An exploration of Donald Trump’s allegations of massive voter fraud in the 2016 general election. Electoral studies, 51, 123 142. View

Wines, M. (2021, February 27). In Statehouses, stole-election myth fuels a G.O.P. drive to rewrite rules. The New York Times. View

Brennan Center for Justice. (2021, May). Voting laws roundup: May 2021. View

Bentele, K. G., & O’Brien, E. E. (2013). “Jim Crow 2.0? Why states consider and adopt restrictive voter access policies,” Perspectives on Politics, 11(4), 1088-1116. View

Lieberman, D. (2012). Barriers to the ballot box: New restrictions underscore the need for voting laws enforcement. Human Rights, 39(1), 2-14. View

Weiser, W. R. & Garber, A. (2025, February 11). SAVE Act would undermine voter registration for all Americans. Brennan Center for Justice. View

Levin-Waldman, O. (2019). Income inequality and disparities in civic participation in the New York City metro area. Regional Labor Review, 15(2), 2-29. View

Levin-Waldman, O. (2012). Rising income inequality and declining civic participation. Challenge, 55(2), 51-70. View

Bleiweis, R., Boesch, D., & Gaines, A. C. (2020, August 3). The basic facts about women in poverty. Center for American Progress. View

Kaplan, J., & Winck, B. (2021, May 30). The truth behind America’s labor shortage is we’re not ready to re-think work. Business Insider. View

Lund, S, Ellingrud, K., Hancock, B., & Manyika, J. (2020, April). Covid-19 and jobs: Monitoring the US impact on people and places. McKinsey Global Institute. COVID-19 and jobs: Monitoring the US impact on people and places (mckinsey. com). View

Oncu, A., & Oncu, T. S. (2021, March 13). The battle of GameStop. Economic and Political Weekly (India). View

Northfield, S. (2000, October 21). Do-it-yourself investors demand fair disclosure. The Globe and Mail.

Matto, E.C. (2025, March 7). The SAVE Act would make it harder to vote—and not just for noncitizens. The Hill. View

Lee, P. D. (2022). American Bar Association advances civic education.” Human Rights, 47(2), 12-14.