Journal of Political Science and Public Opinion Volume 3 (2025), Article ID: JPSPO-128

https://doi.org/10.33790/jpspo1100128Research Article

Party Institutionalization and the Effect of Winning and Losing on Satisfaction with Democracy

Julie VanDusky

Associate Professor, Department of Political Science, Boise State University, Boise, ID, United States.

Corresponding Author: Julie VanDusky, Associate Professor, Department of Political Science, Boise State University, Boise, ID, United States.

Received date: 25th August, 2025

Accepted date: 27th October, 2025

Published date: 29th October, 2025

Citation: VanDusky, J., (2025). Party Institutionalization and the Effect of Winning and Losing on Satisfaction with Democracy. J Poli Sci Publi Opin, 3(2): 128.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Introduction

The body of scholarship on satisfaction with democracy has long recognized the influence that voting for a winning party or candidate has on satisfaction with democracy. That is, winners (or voters who vote for winning parties or candidates) are simply more satisfied with democracy than losers (or voters who vote for losing parties or candidates) are [1-7]. Yet, while winning and losing an election may influence how satisfied voters are, certain characteristics of a country’s political system could influence the impact that winning and losing have on satisfaction. In particular, party institutionalization in a country should impact how winning and losing influence satisfaction with democracy.

In countries where parties are highly institutionalized, parties tend to be older, party labels tend to send meaningful signals about parties’ policy preferences, and links between parties and voters are strong [8]. As such, winning should have a strong positive impact on satisfaction with democracy, and losing should have a strong negative impact on satisfaction. In these systems, winners and losers should be confident that the winning party will pursue a policy agenda that the winning voters will support. As a result, the winners will be very satisfied with democratic outcomes, and the losers will be very unsatisfied [9].

In contrast, in countries where parties are less institutionalized, parties tend to be younger, party labels do not send clear, credible signals about parties’ policy preferences, and links between parties and voters are weak. As such, both winning and losing voters may have limited expectations as to which types of policies the winning party will pursue. Since both winners and losers may not know what to expect from newly elected officials once they take office, both winners and losers may not take into consideration the election results when they are determining how satisfied they are with democracy in their country.

In the data analysis section of the paper, I use data on satisfaction with democracy and vote choice from the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES), Modules 2-5. I focus specifically on analyzing data from presidential systems in the Americas between 2002 and 2021. There is a great deal of variation in party institutionalization throughout the presidential democracies in the Americas. As such, this allows me to analyze the impact that party institutionalization has on satisfaction across a range of countries with varying levels of party institutionalization. In the analysis, I also use data on party institutionalization from the Varieties of Democracy dataset [10,11]. The findings suggest that as party institutionalization increases, voting for the winning presidential party has an increasingly positive impact on satisfaction with democratic outcomes. That is, winners become increasingly more satisfied with democracy than losers are. As such, while election results should have a legitimizing effect on democratic institutions [12], as election losers become increasingly dissatisfied with democracy, election outcomes could actually produce delegitimizing effects.

In the next section of the paper, I summarize the literature on satisfaction with democracy. Afterwards, I discuss how party institutionalization conditions how winning or losing impacts satisfaction with democracy. Then I discuss the research design and empirical results. In the conclusion, I provide suggested avenues for future research on party institutionalization and satisfaction with democracy.

Satisfaction with Democracy

Satisfaction with democracy varies a great deal cross-nationally. A variety of factors can explain this variation in satisfaction between countries throughout the world. One of the most consistent factors that influences satisfaction is government performance. While citizens may have general opinions on how satisfied they are with democracy, government performance still influences their evaluations of regime performance. Citizens simply tend to be more satisfied with democracy as the quality of policy outcomes increases. In particular, Armingeon and Guthtmann [13] find that between 2007 and 2011, the economic crisis in Europe had a negative impact on satisfaction with democracy. Similarly, Cameron [14] finds that rising economic pessimism over time has led to a decline in satisfaction with democracy in Australia. Claassen and Magalhães [15] also find that economic performance has a positive impact on satisfaction with democracy in countries all over the world. Beyond economic indicators, Claassen and Magalhães [15] find that crime rates have a negative impact on satisfaction.

Institutions can also play a key role in satisfaction with democracy. Citizens in consensus democracies tend to be more satisfied with democracy than citizens in majoritarian democracies are. Consensus democracies are designed to include multiple interests within the policymaking process. Given that a variety of interests can influence the policymaking process, this increases satisfaction with democracy overall amongst citizens. In contrast, majoritarian democracies tend to only favor the representation of the majority’s interests throughout the policymaking process. Opposition interests tend to be excluded. As a result, opposition supporters are less satisfied with the democratic process, which reduces overall satisfaction with democracy within the population [1,6,7,16-20].

Another key factor that influences satisfaction with democracy is winning or losing an election. After an election, citizens who voted for candidates and parties that won tend to be more satisfied with democracy than citizens who voted for candidates and parties that did not win [1-3,5,6]. The increase in satisfaction is likely driven by a combination of two factors: ideology and affective polarization. With respect to ideology, when a citizen’s preferred candidate or party controls a key policymaking institution, the candidate or party will develop policies the citizen supports, and this should increase satisfaction with democracy. In contrast, when a citizen loses an election, their representative may not pursue policies the citizen supports, and this should decrease satisfaction [4,21,22]. And the satisfaction gap between winning and losing should become bigger as the perceived ideological gaps between parties grow wider. When parties are perceived to be more ideologically polarized, election winners should be more satisfied with democracy. In contrast, losers should be very unhappy with the outcome because the winning parties will likely adopt policies that are far from the losers’ ideal points. Losing in an ideologically polarized system is very costly [4,9].

Of course, although beyond the scope of this article, it is important to note that psychological factors can also influence how winning and losing impact satisfaction with democracy. Often, voters have an affective, or emotional attachment, to parties. Voters could either feel positive emotions towards their own parties, negative emotions towards opposition parties, or a combination of positive and negative emotions towards their own parties and opposition parties. These emotions might influence how winning and losing influence voters’ satisfaction with democracy. When a voter’s party wins, they may feel more positive emotions, and they may be more satisfied with democracy as a result. In contrast, when their party loses, the loss may trigger feelings of inferiority and a low sense of control. This could lead to feelings of distress, anger, and frustration, and could reduce voters’ satisfaction with democracy [9,23-26].

Party Institutionalization and Satisfaction with Democracy

While many studies find that winning or losing an election can have a positive impact on satisfaction with democracy, none of these studies have focused on how party institutionalization could condition how winning and losing influence satisfaction with democracy. In countries with highly institutionalized parties, party labels send strong signals to voters about a party’s policy goals. As such, election results inform voters about the expected ideological direction of public policy. Hence, in countries with highly institutionalized parties, we should expect that election winners should be highly satisfied with democracy, whereas losers should be highly dissatisfied. In contrast, winning and losing should have a weaker impact on satisfaction with democracy in countries with weakly institutionalized parties. Party labels and election results may not send the same signals about the expected ideological direction of public policy. As a result, election results may not have the same impact on voters’ satisfaction with democracy1.

When parties are highly institutionalized in a country, parties tend to be older and exist over time across election cycles. There are also strong, long-term links between parties and voters. Voters tend to vote for the same parties over time. And party labels send voters information about the ideological preferences of political parties. As such, when a party controls a policymaking institution, it is clear which types of policies they will pursue and whether they can govern. There is also more congruence between voters’ preferences and elected officials’ preferences, which means voters are better represented in the policymaking process [27]. Given these conditions, winning and losing an election in a country with highly institutionalized parties should have a strong impact on satisfaction with democracy. Since party labels are meaningful, winners should expect that the parties they voted for will pursue policies that the winning voters support. This should increase winners’ satisfaction with democracy. Alternatively, losing in a system with highly institutionalized parties should reduce satisfaction. If party labels are meaningful, this implies that the winning party will pursue policies that the losing voters do not support. This should decrease satisfaction [8,12,27-30].

Next, when parties are weakly institutionalized, parties tend to be younger and may only exist for a few election cycles. Additionally, party labels send weaker signals to voters about the ideological preferences of political parties. Parties and their candidates may not be able to credibly commit to pursuing any specific types of policies once they are elected. Additionally, there is a disconnect between voters’ preferences and elected officials’ preferences, implying that voters are not well represented in the policymaking process [27]. Hence, even if a voter’s preferred party won office, the voter may not be confident that the party would be willing and able to pursue policies that the voter supported [8,27-30]. As a result, in countries with weakly institutionalized parties, winning and losing an election should have a minimal impact on satisfaction with democracy because voters have limited expectations about which policies parties will pursue in office.

The aforementioned discussion implies that party institutionalization conditions how winning and losing influence satisfaction with democracy. In countries with highly institutionalized parties, winning should have a strong positive impact on satisfaction with democracy, and losing should have a strong negative impact. In contrast, in countries with weakly institutionalized parties, winning should have a limited positive impact on satisfaction, and losing should have a weak negative impact on satisfaction. This leads to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: The positive effect of being an election winner on satisfaction with democracy should increase as party institutionalization increases.

Research Design

In the data analysis, I use data from the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES), Modules 2-5. I include data from 22 presidential elections in the Americas: Brazil (2002, 2006, 2014, 2018), Chile (2005, 2017), Costa Rica (2018), El Salvador (2019), Mexico (2006, 2012, 2018), Peru (2006, 2011, 2016, 2021), the United States (2004, 2008, 2012, 2016, 2020), and Uruguay (2009, 2019). I choose to focus on presidential systems because it is clearer who the winner is after the election. Additionally, previous studies have demonstrated that winning and losing have a stronger impact on satisfaction with democracy in majoritarian democracies than in consensus democracies, and presidential elections are inherently majoritarian.

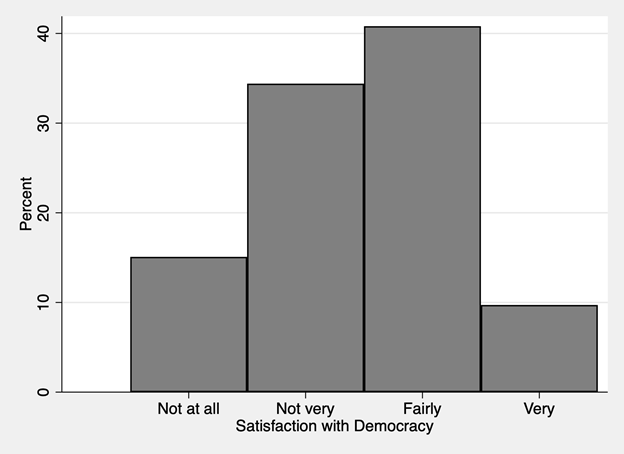

I use the following question from the CSES to measure Satisfaction with Democracy: “On the whole, are you very satisfied, fairly satisfied, not very satisfied, or not at all satisfied with the way democracy works in [COUNTRY]?” I code the answers such that higher values indicate the respondent is more satisfied with democracy. I present a bar chart of the variable in Figure 1. The modal category is 3, “Fairly Satisfied.”

To measure winning an election, I use data from the CSES on who each respondent voted for in the previous election. If they voted for the winning candidate, Winner is coded as 1. If they voted for a losing candidate, Winner is coded as 0. Note that this analysis only focuses on how winning or losing an election influences how satisfied voters are with democracy. Since non-voters did not cast a vote preference for a candidate, there is no way to measure who their preferred candidate(s) were, and therefore no way to assess whether their preferred candidate(s) won or lost. As such, non-voters cannot be included in the analysis.

Also note that several of the countries in the dataset have majority runoff presidential elections. As such, I ran two separate sets of models: (1) “first-round” models that include all the data from the presidential elections with just one round and data from the first round of each presidential election, and (2) “final-round” models that contain data from the presidential elections with just one round and data from the second-round elections (if available). Brazil is the only country in the dataset that consistently includes data for the second round of elections. As such, there are fewer election-years in the “final-round” models.

See Appendix A for summary statistics on actual voter turnout in each country-election-year. Note that the mean of the percentage of respondents in each CSES dataset that indicated they voted in each election for each country-election-year (x̄ First Round = 86.7%; x̄ First Round = 85.0%) was slightly higher than the mean of actual voter turnout (x̄ First Round = 72.0%; x̄ First Round = 69.9%). The mean for the percentage of CSES respondents who said they voted is likely slightly higher than the mean of actual voter turnout because of (1) social desirability bias and (2) voters are more likely to want to participate in an election survey than non-voters are. Nevertheless, while the percentage of people who indicated they voted was higher in CSES, the percentage of respondents who said they voted for the winning candidate (x̄ First Round = 48.1%; x̄ First Round = 56.5%) was generally close to the winning candidate’s vote share in each election year (x̄ First Round = 40.9%; x̄ First Round = 51.6%).

Next, to account for the effect that Winner will have on Satisfaction with Democracy conditional on Party Institutionalization in a country, I use a variable from the V-Dem dataset, party institutionalization, that measures the average institutionalization of all major parties in a country in a given year [10,11,31]. To measure this variable, the authors of the dataset combine five other variables in the dataset: party organizations, party branches, party linkages, distinct party platforms, and legislative party cohesion. For each of these components, the authors of the dataset asked country-expert respondents questions related to (1) whether national parties have permanent organizations, (2) whether parties have local branches, (3) whether parties are clientelistic or programmatic, (4) whether parties have distinct party platforms, and (5) whether legislators vote with their parties on bills in the legislative process. Higher values of this variable indicate that a country has parties that have permanent national organizations, local ties, programmatic linkages with voters, and distinct party platforms. Higher values also indicate that legislators in a country tend to vote along party lines. This variable captures how institutionalized all parties are in general in a country. For this variable, I use data for each country during each election-year. The variable ranges from 0.32 to 0.963 in Models 1 and 3 and 0.38 to 0.963 in Models 2 and 4.

Given that I expect that the Party Institutionalization variable to condition the impact that the Winner variable has on Satisfaction with Democracy, I include an interaction variable in the models between the Winner variable and the Party Institutionalization variable. As per Hypothesis 1, I expect the Winner variable to have a positive impact on Satisfaction with Democracy. But I also expect that effect to become increasingly positive as the Party Institutionalization variables increase [32,33].

I also include several control variables in the models that could also impact respondents’ Satisfaction with Democracy in their respective countries. I include three variables related to economic performance: an individual’s Income, GDP per capita (logged), and the Unemployment Rate. I expect Income and GDP per capita to have a positive impact on Satisfaction with Democracy, and Unemployment Rate to have a negative impact. Several studies have demonstrated that economic performance has a strong impact on citizens’ satisfaction with democracy [13-15].

I also include a control variable in the analysis that accounts for how the Age of Democracy can influence Satisfaction with Democracy. This variable simply measures the number of consecutive years the country had been classified as Free according to the Freedom House dataset as of the year of the election [34]. I expect this variable to have a positive impact on Satisfaction with Democracy.

Lastly, note that ideally, I would include additional individual- level demographic control variables in the analysis, such as age and gender. However, the data for these variables are not available in all country-years in the CSES.

Results

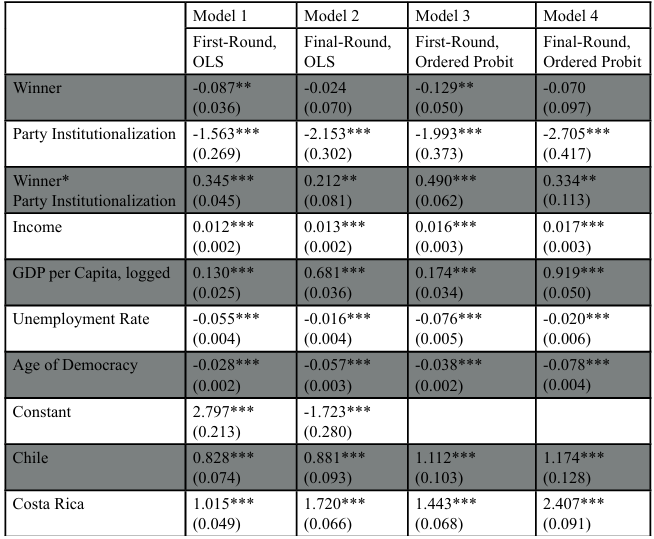

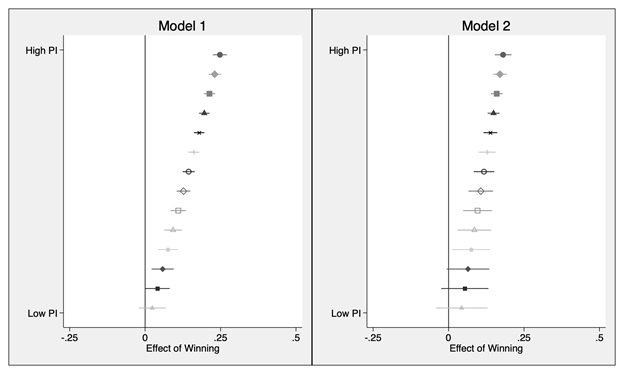

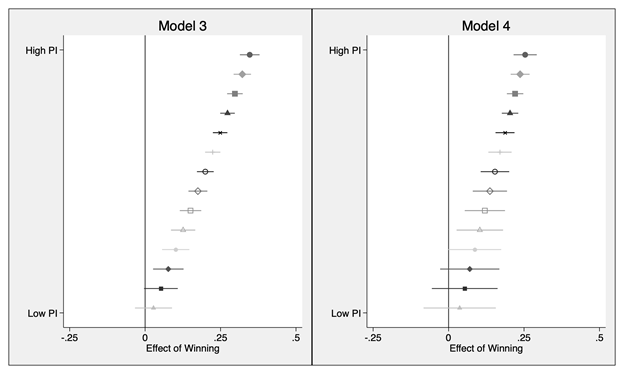

I present the results of Models 1-4 in Table 1 and Figures 2-3. Models 1-2 use ordinary least squares regression. Models 3-4 use ordered probit to analyze the data. All of the models include fixed effects for each country, with Brazil as the base category.

The results from the coefficient plots in Figures 2-3 provide strong support for Hypothesis 1. At the lowest levels of party institutionalization, winning has no statistical impact on satisfaction with democracy. But at the highest levels of party institutionalization, winning has a positive impact on satisfaction with democracy. Substantively, in Models 1-2, at the highest levels of party institutionalization, being a winner leads to about a 0.181 to 0.248 unit increase (or a 5% to 6% increase) in satisfaction with democracy. In Model 3, at the highest levels of party institutionalization, winners have a 32.2% probability of choosing “Fairly Satisfied” with democracy and a 15.9% probability of choosing “Very Satisfied” with democracy, while losers have a 30.0% probability of choosing “Fairly Satisfied” with democracy and a 10.3% probability of choosing “Very Satisfied” with democracy. Similarly, in Model 4, winners have a 36.0% probability of choosing “Fairly Satisfied” with democracy and a 14.6% probability of choosing “Very Satisfied” with democracy, while losers have a 33.9% probability of choosing “Fairly Satisfied” with democracy and a 10.4% probability of choosing “Very Satisfied” with democracy.

Table 1: The Impact of Winner on Satisfaction with Democracy Conditional on Party Institutionalization

Figure 2: The Effect of Winner on Satisfaction with Democracy Conditional on Party Institutionalization, Models 1-2 (OLS)

Figure 3: The Effect of Winner on Satisfaction with Democracy Conditional on Party Institutionalization, Models 3-4 (Ordered Probit)

With respect to the control variables, the coefficient for Income is positive and significant at the 0.001 level in all of the models. As expected, the results suggest that as an individual’s income increases, their satisfaction with democracy increases. The coefficient for GDP per Capita is also positive and significant at the 0.001 level in all of the models. And the coefficient for the Unemployment Rate is negative and significant at the 0.001 level in all of the models. As expected, these results suggest that as a country’s overall economic health increases, individuals within that country become more satisfied with democracy. Lastly, Age of Democracy does not have the expected effect.

Robustness Checks

Since a handful of countries only had one election cycle in the dataset, I re-run Models 1-4, only including countries with multiple election cycles. Specifically, I remove the observations from Costa Rica and El Salvador in Models 1 and 3, and the observations from Chile, Costa Rica, and Peru from Models 2 and 4. I present the results for these new models in Appendix B, Table B1, and Figures B1 and B2. The results of the models are substantively the same as the original models. As party institutionalization increases, the effect of winning on satisfaction with democracy becomes increasingly positive. Note that since I removed observations from Models 2 and 4, party institutionalization in those models only ranges from 0.719 to 0.963 (as opposed to the original models, where it ranges from 0.380 to 0.963).

Next, I also re-run the models excluding the United States and only including the Latin American countries. The results for these models are in Appendix C, Table C1, and Figures C1 and C2. The results for Models C1 and C3 are substantively the same as the original models. Winners become increasingly more satisfied with democracy as party institutionalization increases. The results for Models C2 and C4 are different. Winning has a positive impact on satisfaction with democracy regardless of the level of party institutionalization.

Given that the fixed effects were significant in most cases, I re-run the models without the fixed effects. I present the results in Appendix D, Table D1, and Figures D1 and D2. The substantive results for the Winner and Party Institutionalization variables remain the same. As party institutionalization increases, the positive impact that winning has on satisfaction increases. Nevertheless, the R-Square values were lower in the models without the fixed effects, indicating that the fixed effects in the original model account for some of the cross-national variation in satisfaction with democracy. Additionally, the results for the control variables in Models D1-D4 were slightly different. The coefficient for GDP per Capita lost significance in Models D1 and D3, and the coefficient for the Unemployment Rate lost significance in Models D2 and D3. And the coefficient for Age of Democracy became positive. Hence, including the fixed effects affected the results for the control variables, but not the main variables of theoretical interest (i.e. Winner and Party Institutionalization).

Lastly, to assess the general impact of winning on satisfaction with democracy, conditional on party institutionalization, I display the distribution of Satisfaction with Democracy for winners and losers for each election year in the histograms in Figures E1-E15 in Appendix E. I display each country from the lowest average level of party institutionalization (Peru) to the highest average level (Uruguay). I display the first-round models first and the second-round models second. Overall, even without accounting for the control variables, the results suggest that as party institutionalization increases, winners become increasingly more satisfied with democracy than losers are.

Conclusion

While being an election winner or election loser might influence satisfaction with democracy, the exact impact it will have on satisfaction with democracy will depend on other conditions in the political system. In this article, I demonstrate how party institutionalization conditions the impact that winning has on satisfaction with democracy. In countries that have less institutionalized parties, winners tend to be as equally satisfied with democracy as losers are. But as parties become more institutionalized, winners become more satisfied with democracy than losers are.

These findings are not surprising given that the analysis focuses on presidential elections. Majoritarian elections tend to produce clear winners and losers, and as such, it is easy for voters to discern how winning and losing an election can impact policy outcomes. In future studies, scholars could extend this analysis to consensus democracies where the gap between the perceived benefits of winning and losing an election is smaller. Winning and losing may not have as big of an impact on satisfaction with democracy in these countries. As such, party institutionalization may also not play as big of a role in influencing how winning impacts satisfaction with democracy [30].

It is also important to note that in this analysis, none of the countries experienced large changes in party institutionalization. In future research, scholars could focus on how changes in party institutionalization in both the short-run and long-run impact how winning and losing influence satisfaction with democracy. Changes to party institutionalization may indicate broader changes to the overall democratic system in the country, and this might impact how winning influences satisfaction with democracy. If the links between parties and voters become weaker, we should expect the impact that winning has on satisfaction to diminish. Alternatively, if those links become stronger, we should expect the impact of winning on satisfaction with democracy to grow over time.

Additionally, this article focused on how party institutionalization influences satisfaction with democracy for voters after an election. Future studies could also focus on the effect of party institutionalization on satisfaction with democracy in general. Citizens should be more satisfied with democracy as party institutionalization increases. In countries with a high level of party institutionalization, it is easier for citizens to predict which parties will compete from election to election, party labels send more meaningful signals to citizens about what the parties stand for, and voters have an easier time predicting what parties will do in office if they are elected. Nevertheless, as the results of this analysis suggest, even in countries with highly institutionalized parties, where citizens should generally be satisfied with democracy, citizens who do not support the parties in power for ideological reasons may still be less satisfied with democracy. And this may be even more the case in countries with high levels of affective polarization [35].

Lastly, the results of this article are interesting because, generally speaking, party institutionalization should also have a positive impact on the quality of a democracy. When parties are stable from election to election, when party labels communicate meaningful information about parties’ policy preferences, and when links between parties and voters are strong, parties play a key role in representing voters’ interests in government. Yet, the results of this analysis suggest that party institutionalization can negatively impact democratic outcomes if it causes some voters to become dissatisfied with democratic outcomes when they lose an election. This is important to note as it illustrates the complex impact a specific characteristic of a political system could have on the quality of democratic outcomes in a country. Ideally, elections should play a key role in the democratic process, as they help legitimize the rule of public officials in the short run [12]. But if party institutionalization leads to losers becoming unsatisfied with democracy, election outcomes may have a minimal effect on legitimacy, or even a negative effect.

Competing Interests:

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

Anderson, Christopher. (2005). Losers' Consent: Elections and Democratic Legitimacy. New York: Oxford University Press. View

Anderson, Christopher J., and Christine A. Guillory. (1997). "Political Institutions and Satisfaction with Democracy: A Cross-National Analysis of Consensus and Majoritarian Systems." American Political Science Review, 91(1): 66-81. View

Blais, André, Alexandre Morin-Chassé, and Shane P. Singh. (2017). "Election Outcomes, Legislative Representation, and Satisfaction with Democracy." Party Politics, 23(2): 85-95. View

Curini, Luigi, Willy Jou, and Vincenzo Memoli. (2012). "Satisfaction with democracy and the winner/loser debate: The role of policy preferences and past experience." British Journal of Political Science, 42(2): 241-261. View

Singh, Shane, Ekrem Karakoç, and André Blais. (2012). “Differentiating winners: How elections affect satisfaction with democracy.” Electoral Studies, 31(1): 201-211. View

VanDusky-Allen, Julie. (2017). "Winners, losers, and protest behavior in parliamentary systems." The Social Science Journal, 54(1): 30-38. View

Van Dusky-Allen, Julie, and Stephen M. Utych. (2021). "The effect of partisan representation at different levels of government on satisfaction with democracy in the United States." State Politics & Policy Quarterly, 21(4): 403-429. View

Casal Bértoa, Fernando, Zsolt Enyedi, and Martin Mölder. 2024. "Party and Party System Institutionalization: Which Comes First?" Perspectives on Politics, 22(1): 194-212. View

Janssen, Lisa. (2023). "Sweet victory, bitter defeat: The amplifying effects of affective and perceived ideological polarization on the winner–loser gap in political support." European Journal of Political Research. View

Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, David Altman, Michael Bernhard, Agnes Cornell, M. Steven Fish, Lisa Gastaldi, Haakon Gjerløw, Adam Glynn, Sandra Grahn, Allen Hicken, Katrin Kinzelbach, Kyle L. Marquardt, Kelly McMann, Valeriya Mechkova, Pamela Paxton, Daniel Pemstein, Johannes von Römer, Brigitte Seim, Rachel Sigman, Svend-Erik Skaaning, Jeffrey Staton, Eitan Tzelgov, Luca Uberti, Yi-ting Wang, Tore Wig, and Daniel Ziblatt. (2022). "V-Dem Codebook v12." Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. View

Lindberg, Staffan I., Nils Düpont, Masaaki Higashijima, Yaman Berker Kavasoglu, Kyle L. Marquardt, Michael Bernhard, Holger Döring, Allen Hicken, Melis Laebens, Juraj Medzihorsky, Anja Neundorf, Ora John Reuter, Saskia Ruth–Lovell, Keith R. Weghorst, Nina Wiesehomeier, Joseph Wright, Nazifa Alizada, Paul Bederke, Lisa Gastaldi, Sandra Grahn, Garry Hindle, Nina Ilchenko, Johannes von Römer, Steven Wilson, Daniel Pemstein, and Brigitte Seim. (2022). “Codebook Varieties of Party Identity and Organization (V–Party) V2”. Varieties of Democracy (V Dem) Project. View

Spitz, Elaine. (1984). Majority Rule. Chatham, New Jersey: Chatham House Publishers, Inc. View

Armingeon, Klaus, and Kai Guthmann. (2014). "Democracy in crisis? The declining support for national democracy in European countries, 2007–2011." European Journal of Political Research, 53(3): 423-442. View

Cameron, Sarah. (2020). "Government performance and dissatisfaction with democracy in Australia." Australian Journal of Political Science, 55(2): 170-190. View

Claassen, Christopher, and Pedro C. Magalhães. 2022. "Effective government and evaluations of democracy." Comparative Political Studies, 55(5): 869-894. View

Aarts, Kees, and Jacques Thomassen. (2008). "Satisfaction with democracy: Do institutions matter?" Electoral Studies, 27(1): 5-18. View

Bernhard, Michael, Timothy Nordstrom, and Christopher Reenock. (2001). "Economic performance, institutional intermediation, and democratic survival." Journal of Politics, 63(3): 775-803.View

Lijphart, Arend. (1999). Patterns of Democracy: Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries. Yale University Press. View

McDonald, Michael D., Silvia M. Mendes, and Ian Budge. (2004). "What are elections for? Conferring the median mandate." British Journal of Political Science, 34(1): 1-26. View

Powell, G. Bingham, and G. Bingham Powell Jr. (2000). Elections as Instruments of Democracy: Majoritarian and Proportional Visions. New Haven: Yale University Press. View

Ferland, Benjamin. (2021). “Policy congruence and its impact on satisfaction with democracy.” Electoral Studies, 69: 102204. View

Stecker, Christian, and Markus Tausendpfund. (2016). "Multidimensional government-citizen congruence and satisfaction with democracy." European Journal of Political Research, 55(3): 492-511. View

Dias, Nicholas, and Yphtach Lelkes. (2022). "The nature of affective polarization: Disentangling policy disagreement from partisan identity." American Journal of Political Science, 66(3): 775-790. View

Gidron, Noam, James Adams, and Will Horne. (2020). American Affective Polarization in Comparative Perspective. Cambridge University Press. View

Hobolt, Sara B., Thomas J. Leeper, and James Tilley. (2021). "Divided by the vote: Affective polarization in the wake of the Brexit referendum." British Journal of Political Science, 51(4): 1476-1493. View

Reiljan, Andres, Diego Garzia, Frederico Ferreira Da Silva, and Alexander H. Trechsel. (2023). "Patterns of affective polarization toward parties and leaders across the democratic world." American Political Science Review. View

Luna, Juan P., and Elizabeth J. Zechmeister. (2005). "Political representation in Latin America: a study of elite-mass congruence in nine countries." Comparative Political Studies, 38(4): 388-416. View

Dalton, Russell J., and Steven A. Weldon. (2005). "Public images of political parties: A necessary evil?" West European Politics, 28(5): 931-951. View

Lupu, Noam. (2016). Party Brands in Crisis: Partisanship, Brand Dilution, and the Breakdown of Political Parties in Latin America. Cambridge University Press. View

Nemčok, Miroslav and Hanna Wass. (2021). “As time goes by, the same sentiments apply? Stability of voter satisfaction with democracy during the electoral cycle in 31 countries.” Party Politics, 27(5): 1017-1030. View

Bizzarro, Fernado, Allen Hicken, and Darin Self. (2017). “The V-Dem party institutionalization index: a new global indicator (1900-2015).” V-Dem Working Paper, 48. View

Brambor, Thomas, William Roberts Clark, and Matt Golder. (2006). "Understanding interaction models: Improving empirical analyses." Political Analysis, 14(1): 63-82. View

Friedrich, Robert J. (1982). "In defense of multiplicative terms in multiple regression equations." American Journal of Political Science: 797-833. View

Freedom House. (2022). Freedom in the World Dataset. View

Ridge, Hannah M. (2023). "Party system institutionalization, partisan affect, and satisfaction with democracy." Party Politics, 29(6): 1013-1023. View