Journal of Political Science and Public Opinion Volume 3 (2025), Article ID: JPSPO-130

https://doi.org/10.33790/jpspo1100130Research Article

Religious Governance and Human Rights Compliance: Developing Assessment Indicators from ICCPR and ICESCR

Chih-Chieh Chou

Professor, Department of Political Science, National Cheng Kung University, No.1, University Road, Tainan City 701, Taiwan.

Corresponding Author: Chih-Chieh Chou, Professor, Department of Political Science, National Cheng Kung University, No.1, University Road, Tainan City 701, Taiwan.

Received date: 04th November, 2025

Accepted date: 09th December, 2025

Published date: 11th December, 2025

Citation: Chou, C. C., (2025). Religious Governance and Human Rights Compliance: Developing Assessment Indicators from ICCPR and ICESCR. J Poli Sci Publi Opin, 3(2): 130.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Abstract

This article develops a comprehensive framework for assessing religious governance regulations against international human rights norms, drawing primarily on the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). It first analyzes the provisions and general comments concerning freedom of religion or belief, and identifies three foundational principles: comprehensiveness and autonomy in religious practice, permissible limitations and proportionality, and freedom of religious education. It then proposes eight indicators to evaluate whether domestic religious governance legislation complies with international human rights standards: religious financial autonomy, religious land use, legal status of religious organizations, scope of religious education, democratic governance within religious bodies, non-discrimination, adherent-organization relations, and religion-environment relations. Using examples from Japan, the United States and broader comparative practice, the article illustrates how these indicators can guide legislative design and policy evaluation. Finally, it sets out core legislative principles and model provisions that translate treaty obligations into operational rules, aiming to help governments balance the protection of religious freedom with the maintenance of public order and other legitimate interests. This research contributes to scholarship on religious governance by translating abstract treaty obligations into concrete assessment criteria, offering practical guidance for policymakers seeking to harmonize religious governance frameworks with international human rights commitments.

Keywords: Religious Governance, Freedom of Belief, ICCPR, ICESCR, Religious Regulatory Framework, State-Religion Relations, Human Rights Compliance

Introduction

The relationship between religious freedom and state governance covering both church-state relations and the interaction between religious organizations and secular society—has long been a central concern in democratic politics. Different countries adopt different institutional designs. The United States uses a combination of constitutional guarantees, tax law, and land-use regulations to structure the public presence of religion, whereas Japan and Taiwan rely more explicitly on dedicated religious corporation legislation or general nonprofit laws [1]. Against this background, religious governance and freedom of religion or belief have become key benchmarks for evaluating democratic quality and human rights performance.

From an international human rights perspective, freedom of religion or belief is unusual in that it is expressly protected in both of the twin human rights covenants: the ICCPR, which codifies mainly civil and political rights, and the ICESCR, which focuses on economic, social and cultural rights. First-generation rights concern civil and political liberties, second-generation rights concern subsistence and social welfare, and so-called third-generation rights highlight collective self determination, intergroup solidarity and environmental protection [2-5]. Religious freedom thus straddles all three generations: it is a civil right to choose, change or reject religion free from coercion; a cultural right to participate in religious rituals, institutions and community life; and, increasingly, a collective right implicated in environmental stewardship and the protection of sacred sites and cultural landscapes [6].

Understanding the alignment between international human rights norms and domestic religious governance frameworks concerns not merely the formal adoption of treaty obligations, but whether and how global human rights standards influence the legitimacy of state action. Scholars of compliance and internalization argue that international norms influence states through processes of socialization, acculturation and legal incorporation; over time, treaty standards come to be treated as legitimate domestic benchmarks for both officials and citizens [7,8]. The central question is how international human rights covenants shape sovereign states and their human rights practices through legalization and domestic implementation. This process involves a dynamic balance between the subjectivity of national sovereignty and the normativity of international norms during their reception and internalization by state authorities.

The aim of this article is twofold. First, it distills from the ICCPR, ICESCR and their general comments a set of core principles for protecting freedom of religion or belief: comprehensiveness and organizational autonomy, permissible limitations and proportionality, and freedom of religious education. Second, it translates these principles into eight concrete indicators and a set of model legislative provisions that can be used to evaluate and reform national religious governance frameworks. The focus is on developing a portable analytical tool rather than providing exhaustive country case studies; nonetheless, illustrative examples from Japan, the United States, Europe and other regions are used where appropriate to demonstrate how the indicators can be operationalized [9].

International Human Rights Law on Freedom of Religion or Belief

Three instruments form the backbone of the global normative framework on freedom of religion or belief: the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), the ICCPR and the ICESCR. Article 18 of the UDHR declares that everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion, a principle subsequently elaborated in binding treaty form. The ICCPR and ICESCR then transform this declaration into binding treaty obligations for states parties [2-4].

ICCPR Article 18(1) protects the freedom to have or adopt a religion or belief of one's choice and to manifest it individually or in community, in public or private. This provision encompasses both the internal forum—the right to hold or change beliefs without interference—and the external forum, which includes worship, observance, practice and teaching. ICESCR Article 15(1)(a) recognizes the right of everyone to take part in cultural life, which includes religious systems, rituals and ceremonies. Together, these provisions establish that religious freedom is both an individual civil liberty and a collective cultural entitlement requiring affirmative state support [10].

General Comment No. 22 of the Human Rights Committee clarifies that the term "religion or belief" covers theistic, non-theistic and atheistic beliefs, as well as the right not to profess any religion at all. It emphasizes that protected manifestations of religion or belief include worship, observance, practice and teaching, and lists concrete examples: building places of worship, displaying symbols, observing holidays, proselytizing, and establishing religious schools and seminaries [6]. General Comment No. 21 of the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights similarly stresses that religious traditions and institutions are integral parts of cultural life, and that states must take positive steps to ensure effective participation in such life, particularly for disadvantaged or minority communities [6].

Both treaties permit limitations on the external manifestation of religion or belief, but only under strict conditions. ICCPR Article 18(3) allows limitations that are prescribed by law and necessary to protect public safety, order, health or morals, or the fundamental rights and freedoms of others. The Human Rights Committee insists that such limitations must be non-discriminatory, directly related to a specific legitimate aim and proportionate to that aim [10]. Limitations must employ the least restrictive means available and must not vitiate the very essence of the protected right. Likewise, General Comment No. 21 requires that limitations on participation in cultural life be strictly necessary, proportionate and based on the least restrictive means available.

These principles also resonate with the broader emerging understanding of the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment, which connects environmental protection and human rights obligations. Religious communities often maintain sacred natural sites, traditional ecological knowledge, and practices that contribute to environmental stewardship, thus linking freedom of religion or belief with third-generation environmental and collective rights [11].

Religious education is an important subset of freedom of religion or belief. ICCPR Article 18(4) explicitly protects the liberty of parents and legal guardians to ensure the religious and moral education of their children in conformity with their own convictions. General Comment No. 22 affirms that this liberty cannot be restricted, while also noting that public education must be neutral and inclusive. The CESCR has emphasized that individuals and communities transmit their values, religion, customs and language through education, and that public schools should teach about religion in an objective and pluralistic way, providing reasonable accommodations or exemptions where confessional instruction is offered [6,10].

Fundamental Principles for Protecting Freedom of Religion or Belief

Synthesizing the treaty texts and general comments, three fundamental principles emerge for protecting freedom of religion or belief. First, comprehensiveness and organizational autonomy: the right covers a wide range of internal and external dimensions and includes the autonomy of religious organizations to manage their basic affairs. Second, permissible limitations and proportionality: restrictions on manifestations of religion are allowed only when they are based on law, pursue a legitimate aim and represent the least restrictive means to achieve that aim. Third, freedom of religious education: states must respect parents' rights and ensure that public education is neutral, pluralistic and accommodating.

Comprehensiveness and Organizational Autonomy

The principle of organizational autonomy recognizes that individuals typically exercise their religious freedom through collective bodies such as churches, temples, mosques and related associations. International norms protect the right of these bodies to select leaders, train clergy, establish seminaries and publish religious texts, free from unjustified state interference. ICCPR Article 18 and General Comment No. 22 confer upon religious organizations the autonomy necessary to fulfill their fundamental religious functions, enumerating several such prerogatives: freedom to select religious leaders, clergy and teachers; freedom to establish seminaries or religious schools; and freedom to produce and distribute religious texts or publications.

At the same time, autonomy is not absolute. It is framed by the requirements of non-discrimination and the protection of other fundamental rights. States may regulate matters such as financial transparency, labor standards or the protection of minors in a way that applies equally to religious and secular organizations, provided that such regulation remains proportionate and respectful of doctrinal independence. ICESCR General Comment No. 21 emphasizes that governments must not directly or indirectly interfere with individuals' rights to participate in "systems of religion or belief, rituals and ceremonies" as components of cultural life, and requires governments to "prevent third parties from interfering with the enjoyment of these rights [12]." Accordingly, the scope of religious organizational autonomy and the calibration of church-state separation should be centered on facilitating and protecting individual freedom of religion or belief and the principle of non-discrimination.

Permissible Limitations and Proportionality

The principles of proportionality and least restrictive means are central to reconciling religious freedom with other public interests. ICCPR Article 18(3) provides that freedom to manifest one's religion or beliefs may be subject only to such limitations as are prescribed by law and are necessary to protect public safety, order, health, or morals or the fundamental rights and freedoms of others. General Comment No. 22 reiterates that even within permissible limitations, restrictions must comply with equality and non-discrimination principles and "must not be applied in a manner that would vitiate the rights guaranteed in article 18." Furthermore, "restrictions must be directly related and proportionate to the specific need on which they are predicated [13]."

These principles require that states consider alternative regulatory options and choose those that interfere least with religious practice, while still effectively protecting public safety, health or the rights of others. This approach has been increasingly adopted in both international and domestic jurisprudence, including decisions of the European Court of Human Rights and national constitutional courts [13]. ICESCR General Comment No. 21 similarly emphasizes that "any limitation must be proportionate, meaning that where several types of limitations may be imposed, the least restrictive measure must be adopted." Moreover, governmental limitations on cultural life must consider whether such restrictions affect rights having "inherent connection" with the right to participate in cultural life, such as freedom of religion or belief.

Freedom of Religious Education

Regarding religious education, ICCPR Article 18(1) guarantees "freedom to teach a religion or belief," and paragraph 4 further emphasizes respect for "the liberty of parents and, when applicable, legal guardians to ensure the religious and moral education of their children in conformity with their own convictions." General Comment No. 22 reinforces that "the freedom of parents or legal guardians to ensure religious and moral education cannot be restricted." Additionally, ICESCR General Comment No. 21 affirms that "individuals and communities transmit their values, religion, customs, language and other cultural references through education." However, public school instruction concerning religion and ethics in general historical education should employ neutral and objective teaching methods. Moreover, within public education systems, particular religions or beliefs should not be taught "unless provision is made for non-discriminatory exemptions or alternatives that would accommodate the wishes of parents and guardians." Furthermore, "those who hold non-religious convictions should enjoy similar protection," without restriction on their education or compulsion to alter their beliefs.

Balancing State Religious Governance with Freedom of Religion

In many constitutional systems, the principles derived from the ICCPR and ICESCR are reflected in doctrines of state neutrality and church-state separation. From the foregoing analysis, governments must balance public interest with constitutional principles of religious freedom when formulating and implementing religious regulations. The principle of church-state separation and neutrality constitutes a foundational norm established by both covenants and national constitutions. Japan's Constitution, for example, guarantees freedom of religion in Article 20 and prohibits the state from engaging in religious activities or providing public funds for religious organizations under Article 89. The Supreme Court's landmark Tsu City Groundbreaking Ceremony judgment developed a "purpose and effect" test to determine whether state involvement in religious ceremonies violates constitutional neutrality [14,15]. In the United States, the First Amendment bars establishment of religion and protects free exercise, and recent Supreme Court decisions have refined the standards for assessing public religious expression and workplace accommodation [16].

Neutrality, however, does not mean that the state must be indifferent to risks arising in religious contexts. Governments retain a duty to protect public order, safety and the rights of vulnerable persons. The challenge is to design regulatory responses that are targeted and proportionate. The 1995 sarin gas attack by the Aum Shinrikyō cult on the Tokyo subway prompted Japan to amend its Religious Juridical Persons Law, introducing enhanced disclosure requirements and oversight powers for religious corporations. These reforms were framed as neutral, generally applicable measures aimed at preventing the abuse of organizational status rather than suppressing religion as such, and thus provide an example of a proportionate regulatory response [17].

Such measures constitute reasonable regulation within legal bounds for public safety rather than religiously motivated intervention. Conversely, governmental regulations exceeding the scope permitted by both covenants—such as discriminating against religious communities or compelling conversion—potentially violate international obligations. Therefore, religious governance legislation should adhere to fundamental principles of "neither favoring any religion nor compelling anyone to change beliefs," with minimal intervention in religious organizational autonomy while ensuring public interest and social order. Governmental limitations on religious activities must satisfy five criteria: "clear legal basis—legitimate purpose—necessity—least restrictive means—reviewability." Procedurally, governments should ensure prior consultation, public disclosure of reasons, and effective remedies.

Comparative jurisprudence further illustrates the delicate balance between religious freedom and competing interests. The European Court of Human Rights has developed a substantial body of case law under Article 9 of the European Convention on Human Rights, including the landmark Kokkinakis v. Greece judgment, which affirmed that the freedom to manifest religion includes proselytism but allows narrowly tailored restrictions to protect the rights of others [18]. Debates over laïcité in France and pluralist secularism in India similarly show that different constitutional traditions seek to reconcile religious diversity, equality and public order in different ways, while still operating under broadly similar human rights constraints [19].

According to ICCPR General Comment No. 22, religious organizations serve as vehicles for religious freedom, enjoying appropriate autonomy including selecting leaders, establishing educational institutions, financial management, and external religious activities. The ICESCR cultural rights perspective supplements that governments must not arbitrarily restrict participation in religious rituals and ceremonies, and should avoid excluding or disparaging particular religious traditions in education and cultural policies. From a proportional perspective, administrative oversight aimed at maintaining public safety and order should first inventory milder yet equally effective measures (such as information disclosure and procedural regulations), avoiding blanket, permanent, or discriminatory limitations.

Regarding public benefits, if governments provide generally available benefits (such as security subsidies, facility improvements, universal education subsidies), they must not exclude recipients solely based on religious identity; if involving direct subsidization of religious ceremonies or missionary activities, stricter scrutiny of purpose and effect is required to avoid constructively "establishing religion." As previously noted, both covenants encourage religious organizations to actively assist individuals in exercising freedom of belief. However, religious organizations, while enjoying autonomy, bear obligations to comply with generally applicable public interest, labor, safety, fiscal, and information disclosure regulations.

Assessment Indicators and Legislative Principles for Religious Governance

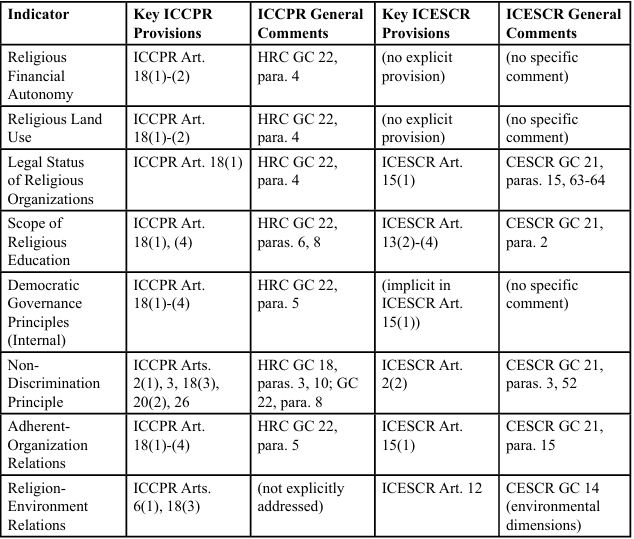

To operationalize these principles, this article proposes eight indicators for assessing whether domestic religious governance frameworks comply with international human rights standards: (1) religious financial autonomy, (2) religious land use, (3) legal status of religious organizations, (4) scope of religious education, (5) internal democratic governance, (6) non-discrimination and equal treatment, (7) adherent-organization relations, and (8) religion-environment relations. Together, these indicators provide an integrated lens for analyzing how laws and policies affect the ability of individuals and communities to exercise freedom of religion or belief.

Table 1 maps each indicator to the relevant provisions of the ICCPR and ICESCR and to key explanatory general comments. For example, religious financial autonomy is linked to ICCPR Article 18 and General Comment No. 22 on organizational affairs; legal status and access to legal personality are linked to ICESCR Article 15 and General Comment No. 21 on participation in cultural life; and non-discrimination draws on ICCPR Articles 2 and 26 and ICESCR Article 2(2). The indicator on religion-environment relations is grounded more indirectly in ICESCR Article 12 on the right to health and the developing recognition of environmental dimensions of human rights. These indicators are not intended as rigid checklists but as analytical prompts. They invite researchers and policymakers to ask systematic questions about the cumulative impact of laws and administrative practices on religious life, and to consider whether apparently neutral regulations might have indirect discriminatory effects on certain communities. The construction and use of human rights indicators as tools for evaluation and policy dialogue has been extensively developed in the scholarly literature and in the practice of international monitoring bodies [20].

For large-scale comparative analysis, the indicators can be complemented by cross-national datasets and typologies of religion-state relations that capture quantitative patterns of religious regulation, discrimination and social conflict [21,22]. Such datasets enable researchers to test hypotheses about the relationships between different forms of state governance and outcomes such as religious freedom, social cohesion and interfaith cooperation. However, quantitative approaches must be combined with qualitative assessments that attend to the specific institutional, cultural and historical contexts in which religious governance operates.

Core Legislative Principles for Religious Governance

Building on the indicators, this article sets out model legislative provisions that embody the core principles derived from the covenants. These provisions include a purpose clause emphasizing the dual goals of protecting freedom of religion or belief and maintaining public order; definitions of religion or belief and religious activity; a strong non-discrimination clause; a proportionality and least-restrictive means clause; rules on state neutrality in funding; recognition of organizational autonomy coupled with general accountability for financial and child-protection matters; provisions on religious education and schools; and guarantees of access to effective remedies and periodic review.

Article 1 (Purpose): To implement freedom of religion or belief and the right to participate in cultural life, ensure state neutrality and proportionality, and establish balance between religious organizational autonomy and public accountability.

Article 2 (Definitions): Religion or belief encompasses theism, non- theism, and atheism; religious activities include worship, observance, proselytism, education, association, and necessary preparatory acts.

Article 3 (Non-Discrimination): No person shall be subjected to differential treatment on grounds of religion or belief; governmental policies and their implementation shall not produce direct or indirect discriminatory effects.

Article 4 (Proportionality and Least Restrictive Means): Limitations on external religious manifestation must be based on law, pursue legitimate aims, and satisfy necessity, least restrictive means, and reviewability requirements.

Article 5 (Neutrality in Public Benefits): Universal public benefits and subsidies shall apply equally to religious and non-religious entities; expenditures directly supporting religious ceremonies or proselytism shall be subject to strict scrutiny to avoid endorsement or advancement.

Article 6 (Autonomy and Accountability): Religious organizations possess the right to manage internal affairs according to their doctrines; governments may establish generally applicable regulations concerning financial disclosure, protection of minors, labor rights, and public interest matters through least restrictive means.

Article 7 (Education and Schools): Religious instruction in public schools shall employ objective, neutral, and pluralistic approaches; students and parents enjoy rights of choice or exemption; teachers' personal religious expression shall be appropriately separated from official duties to avoid de facto coercion.

Article 8 (Religious Land and Facilities): Land use and historic preservation regulations shall be religiously neutral; approval of religious facilities shall not be disadvantaged on religious grounds; however, neutral general conditions may be established for safety, environmental protection, and cultural heritage preservation.Article 9 (Remedies): Those aggrieved by administrative dispositions or subsidy decisions may seek review through administrative litigation and judicial remedies; courts shall apply proportionality and non-discrimination principles in adjudication.

Article 10 (International Alignment): Competent authorities shall periodically review implementation of this law, referring to general comments on the ICCPR and ICESCR and comparative legal developments, and submit improvement reports.

Conclusion

Freedom of religion or belief is a complex right that straddles the boundaries between individual conscience, collective identity and public order. It has both civil and cultural dimensions and increasingly intersects with third-generation rights such as environmental protection and collective self-determination. The ICCPR and ICESCR, together with their general comments and related case law, provide states with a detailed but flexible framework for reconciling religious freedom with other legitimate concerns.

This paper has proposed eight indicators and a set of legislative principles for evaluating and reforming domestic religious governance frameworks in light of international human rights standards. The analytical framework is intended to be generalizable and can be applied to assess how well different systems protect freedom of religion or belief, avoid discrimination, and design proportionate responses to genuine public risks. While the examples have focused mainly on Japan, the United States and selected European and Asian experiences, the underlying principles and assessment criteria are applicable across a wide range of constitutional and cultural contexts.

From an international human rights law perspective, the core of protecting freedom of religion or belief lies in "non-discrimination," "individual freedom of choice and expression," and "religious organizational autonomy within necessary limits." National religious governance legislation should align with these principles. Religious organizations not only possess rights to participate in policymaking affecting their "systems of religion or belief, rituals and ceremonies," but as members of civil society, they also bear obligations to implement these cultural rights. Correspondingly, other individuals, associations, and groups within civil society possess rights to articulate their own positions, perspectives, and concerns.

Effective religious governance requires more than formal compliance with treaties. It demands ongoing engagement between state institutions, religious communities and civil society to interpret and apply human rights norms in context. The indicators and model provisions offered here are intended as tools for that engagement, helping to identify gaps, highlight good practices and support reforms that advance both religious freedom and broader human rights goals.

These analytical syntheses and indicator constructions should facilitate broader and deeper analysis and argumentation regarding alignment between religious governance legislation and international human rights law. Moreover, they can provide governments with evaluative standards and principles for reviewing religious governance systems and decision-making frameworks, enabling balance between protecting religious freedom and maintaining social order, as well as equilibrium in interactions between adherents and religious personnel.

More importantly, formulation or amendment of religious governance regulations requires comprehensive reference to ICCPR Article 18, ICESCR Article 15, and their general comments, incorporating the indicators and principled provisions enumerated above to ensure regulations effectively manage religious activities while protecting exercise of freedom of belief. Governments and legislatures should engage in thorough discussion with civil society and draw upon other nations' legislative and practical experiences, continuously reviewing and perfecting religion-related laws to transform them into genuine instruments for implementing constitutional and covenant-based religious rights protections.

Governments bear obligations and responsibilities to proactively guide mediation and negotiation of disputes among parties. ICESCR General Comment No. 21 specifies that governments' concrete legal obligations under the covenant include respecting everyone's right to "participate freely in an active and informed manner, and without discrimination, in any important decision-making process that may have an impact on [their] way of life and on [their] rights." Therefore, when advancing related legislation, governments should proactively consult with religious organizations, resolve misunderstandings, and foster consensus through inclusive dialogue. Only thus can religious governance legal systems achieve their ultimate objective of balancing individual freedom and public interest, creating conditions for pluralistic coexistence and mutual respect among diverse religious and non-religious communities.

Competing Interests:

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgement:

This work is supported by the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC), Taiwan (NSTC 114-2410 H-006-049). I thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments.

References

Finke, R., & Stark, R. (2005). The churching of America, 1776 2005: Winners and losers in our religious economy. Rutgers University Press. View

United Nations General Assembly. (1948). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. UN General Assembly. View

United Nations General Assembly. (1966a). International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. UN General Assembly. View

United Nations General Assembly. (1966b). International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. UN General Assembly. View

Zhou, Z.-J. (2018). Human rights and international relations. In M. Li (Ed.), International relations (pp. 285–310). Future Culture Publishing.

United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. (2009). General Comment No. 21: Right of everyone to take part in cultural life (Article 15, paragraph 1(a), of the Covenant) (E/C.12/GC/21). UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. View

Goodman, R., & Jinks, D. (2008). Incomplete internalization and compliance with human rights law. European Journal of International Law, 19(4), 725–748. View

Koh, H. H. (1997). Why do nations obey international law? Yale Law Journal, 106(8), 2599–2659. View

Ghanea, N., & Stephens, P. (2017). Religion or belief, international human rights law and politics. Oxford University Press.

United Nations Human Rights Committee. (1993). General Comment No. 22: Article 18 (Freedom of thought, conscience or religion) (CCPR/C/21/Rev.1/Add.4). UN Human Rights Committee. View

Knox, J. H., & Boyd, D. R. (2018). The human right to a healthy environment. United Nations Environment Programme. View

Bielefeldt, H., Ghanea, N., & Wiener, M. (2016). Freedom of religion or belief: An international law commentary. Oxford University Press. View

Evans, C. (2001). Freedom of religion under the European Convention on Human Rights. Oxford University Press. View

Constitution of Japan. (1947). The Constitution of Japan. View

Supreme Court of Japan. (1977). Tsu City Groundbreaking Ceremony Case [Grand Bench judgment, 13 July 1977, 31 Minshū 533]. View

Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, 142 S. Ct. 2407 (2022). View

U.S. Department of State. (2001). International religious freedom report: Japan. U.S. Department of State. View

Kokkinakis v. Greece, judgment of 25 May 1993, Reports of Judgments and Decisions 1993-IV. European Court of Human Rights. View

Baubérot, J. (2013). La laïcité falsifiée. La Découverte. View

Landman, T., & Carvalho, E. (2010). Measuring human rights. Routledge. View

Fox, J. (2015). Political secularism, religion, and the state: A time series analysis of worldwide data. Cambridge University Press. View

Grim, B. J., & Finke, R. (2011). The price of freedom denied: Religious persecution and conflict in the twenty-first century. Cambridge University Press. View