Journal of Public Health Issues and Practices Volume 4 (2020), Article ID: JPHIP-159

https://doi.org/10.33790/jphip1100159Review Article

Impact of Campus Tobacco-Free Policy on Tobacco and Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems Initiation and Cessation among Students, Faculty, and Staff

Gabriel Macasiray Garcia*, Ph.D., M.A., M.P.H., Joy Chavez Mapaye, Ph.D., Valeria Delgado Lopez, Erin Roxbury B.S., Neelou Tabatabai-Yazdi $ B.S.

Division of Population Health Sciences, University of Alaska Anchorage, 3211 Providence Dr., BOC3-220, Anchorage, AK 99508, United States

Corresponding Author Details: Gabriel Macasiray Garcia, Division of Population Health Sciences, University of Alaska Anchorage, 3211 Providence Dr., BOC3-220, Anchorage, AK 99508, United States. E-mail: ggarci16@alaska.edu

Received date: 05th February, 2020

Accepted date: 25th February, 2020

Published date: 27th February, 2020

Citation: Garcia, G.M., Mapaye, J.C., Lopez, V.D., Roxbury, E., Yazdi, N.T. (2020). Impact of Campus Tobacco-Free Policy on Tobacco and Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems Initiation and Cessation among Students, Faculty, and Staff. J Pub Health Issue Pract 4(1):159.

Copyright: ©2020, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Abstract

Objective: This study examines the effects of having a tobaccofree policy in three University of Alaska campuses two years postimplementation among students, faculty, and staff. It also identifies factors associated with tobacco cessation and ENDS use.

Methods: Self-administered online survey was conducted in spring 2017 and 2018.

Results: Most of the current tobacco users began using tobacco prior to policy implementation, while most current ENDS users in 2018 started using ENDS when the policy had been in place. Students and those who are younger are more likely to quit tobacco during policy implementation; and males, students, and those who are younger and current tobacco users are more likely to use ENDS.

Conclusions: Study findings suggest that campus tobacco-free policy can promote tobacco cessation and help prevent tobacco initiation. However, such a policy does not necessarily affect ENDS use. Specific groups need additional interventions to assist in tobacco and ENDS cessation.

Keywords: Tobacco-Free Campus; Tobacco Use; Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS)

Introduction

The American College Health Association endorses a comprehensive tobacco-free policy on college campuses nationwide [1]. This means that smoking and/or use of tobacco products should not be allowed in buildings and within the premises of the campus and the college/ university cannot accept any sponsorship, gifts, or grants from tobacco companies. While there were only 586 colleges that were completely smoke-free in 2011, more than 2,100 college campuses nationwide in 2018 have either a comprehensive smoke-free or tobacco-free policy [2]. In October 2009, a model tobacco-free policy from Americans for Nonsmokers’ Rights included the prohibition Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS), which includes e-cigarettes and vapes (Char Day, ANR, Personal Communication, May 16, 2019).

Research has shown a comprehensive smoke or tobacco-free policy at college campuses is beneficial to the campus’ health and environment. Studies suggest a comprehensive smoke-free or tobaccofree policy is associated with lower smoking rates among students [3-4]; reduced likelihood in secondhand smoke exposure [5-6];increased preference to socialize in smoke-free environments [6] and lower amounts of cigarette butt litter on campus [7]. While these findings seem promising from a tobacco prevention and control lens, they have some limitations that lead to new research questions. First, outcomes reported from previous studies on campus tobacco-free policies have been limited to data collected from students. Thus, there is lack of knowledge of whether the campus tobacco-free policy has any effects on tobacco-related behaviors among faculty and staff. Secondly, several of the previous studies on the effect of campus tobacco-free policy on tobacco-related behaviors have focused on the outcome of whether students are current tobacco users or formers tobacco users without any reference to when they started using tobacco or when they quit using tobacco [3-4]. It is possible that the decrease in smoking rates on campus in these studies may be due in part to the downward trend of tobacco use nationwide and not necessarily due to the effects of the campus tobacco-free policy. Thus, research is needed to determine whether initiation or cessation of tobacco use among students occur before or after the tobaccofree policy implementation. Finally, colleges nationwide did not start including language on the prohibition of e-cigarettes and vapes in their tobacco-free policy until 2014 (Americans for Nonsmokers’ Rights, e-mail correspondence, May 16, 2019). Thus, current literature is lacking on whether the addition of ENDS prohibition in the tobacco-free policy has any effect on e-cigarette and vape use on the college community.

All of the campuses in the University of Alaska (UA) system— University of Alaska Anchorage (UAA), University of Alaska Fairbanks (UAF), and University of Alaska Southeast (UAS)— officially adopted a comprehensive tobacco-free policy starting January 2016. Their policy specifically includes prohibition of e-cigarettes and vapes, as well as hookah, and other smoking devices or products (see: https://www.alaska.edu/bor/policy/05-12.pdf).

The efforts of making the UA system tobacco-free cannot be understated. It took more than four years of advocacy from students, faculty, staff, and community partners, specifically from UAA, for the entire UA system to become tobacco free. The major turning point came in the spring of 2014 when a referendum to adopt a smoke-free policy was placed on the student election ballot at UAA. At that time, the smoke-free referendum was met with strong opposition from the student government, fraternities, a few faculty, and some staff.

However, UAA’s smoke-free team—made up of students, faculty, and staff—thrived and eventually became successful in their efforts. The team engaged in consistent communications messaging; involved various groups and stakeholders in their decision-making and activities; remained resilient in the face of opposition; and focused on data/evidence-driven actions. In terms of communications, the team’s message and branding was simple: Love UAA. Messaging focused on respecting each other’s health and the campus environment. In mobilizing the campus, the team followed Glassman and colleagues’ framework, which involved the following six steps: (1) create a committee to drive the process; (2) develop initiatives for the committee to work on; (3) allow student debate; (4) generate publicity; (5) draft potential policy; and (6) reach out to decision makers at the university [8]. The referendum won by just two percentage points, but this victory would eventually lead the UA Board of Regents to adopt not just a smoke-free policy but a tobaccofree policy for the entire UA system.

The UAA Smoke and Tobacco-Free Team has been collecting data on tobacco and tobacco-related behaviors among students, faculty, and staff at all UA campuses since the implementation of the campus tobacco-free policy. Using the data collected by the UAA Smoke and Tobacco-Free Team, this current study seeks to address some of the research gaps on campus tobacco-free policy mentioned earlier. Specifically, this study examines the effects of having a tobacco-free policy in three University of Alaska (UA) campuses after two years of implementation with regard to tobacco and Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS) initiation and cessation among UA students, faculty, and staff. Additionally, this study also identifies factors associated with tobacco cessation and ENDS use among this group post policy implementation.

Methods

Study Design

This study used repeated cross-sectional study design. Data was collected among the three UA campuses via a self-administered online survey distributed to students, faculty, and staff at two time points: spring semester 2017 and spring semester 2018. By spring 2017, all three campuses had already implemented the tobacco-free policy for at least a year.

Sampling Design

A list of all student, faculty, and staff email addresses were obtained from each of the UA campuses with the permission of the appropriate administrators of the campuses. From the list of email addresses, 20% of students and 80% of faculty and staff were randomly sampled to be sent the link to the online survey. These sampling proportions were calculated to produce sufficient sample size of students, faculty, and staff for each of the campuses to be able to generalize the results of the study to the university population [9].

Data Collection

In conducting the spring 2017 and 2018 surveys, the following protocol was followed. First, an email letter was sent out to a random sample of respondents, introducing them to our study and telling them to expect a follow-up email with the online survey link. Three days later, the online survey link was sent out. Every two weeks thereafter, for a total of six weeks, a follow-up/reminder email would be sent to those who have not yet completed the survey. The surveys remained open for a total of three months. An incentive for participation involved a drawing to win one of four gift cards of varying amounts ($100 for first place, $75 for second place, $50 for third place, and $25 for fourth place). All the surveys were self-administered, and took five minutes to complete. The university’s institutional review board reviewed and approved the study.

Variables of Interest

This study had six variables of interest. One was tobacco use status, which had seven outcome categories: current cigarette smoker (smoking cigarettes in the past 30 days), current smoker of other tobacco products (smoking other tobacco products like hookah, bidi, etc. in the past 30 days), current ENDS smoker (smoking e-cigarettes and/or vapes in the past 30 days), current smokeless tobacco user (using smokeless tobacco in the past 30 days), former smoker (previously smoked cigarettes and other tobacco products), former smokeless tobacco user (previously used smokeless tobacco), and never tobacco users (never used tobacco user or ENDS smoker). All current tobacco and ENDS users were asked at what age they began using, while all former tobacco users were asked at what age they quit using. The second variable of interest was awareness of tobacco cessation programs either on campus and/or the statewide Alaska Tobacco Quit Line (which is a phone and online coached cessation intervention). The final four variables of interest were demographic characteristics, which included sex (female or male), university status (student, faculty, or staff), age, and campus affiliation (UAA, UAF, or UAS).

Analysis

Frequencies of all the variables of interest were obtained and compared for the two survey years. Then, rates of initiation of tobacco and ENDS use, as well as rates of cessation of tobacco use were assessed and compared for each survey year. Chi-square tests were conducted to determine if there were significant differences in initiation and cessation rates between the two survey years. To identify the factors significantly associated with quitting tobacco post policy implementation, logistic regression was run, with all the demographic items and awareness of tobacco cessation programs as independent variables. Finally, to identify factors significantly associated with ENDS use, logistic regression was also run, with the independent variables being all the demographic items, as well as the respondents’ tobacco status (i.e., whether they are current smokers, smokeless tobacco user, former smoker, or former smokeless tobacco user). SPSS Version 25 was used in all analyses.

Results

Sample Characteristics

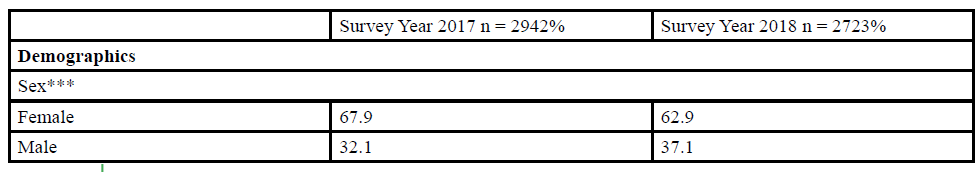

A total of 2,942 students, faculty, and staff at all UA campuses participated in the 2017 survey and 2,723 participated in the 2018 survey. The average response rate for both surveys was 25.8%. For both survey years, more than 60% were females, more than 50% were students, and about 50% were ages 33 years old and above. Most of the participants (59%) were from UAA in 2017, while most (42%) were from UAF in 2018. Overall, the two samples were significantly different in demographic characteristics except for age for the two survey years (see Table 1).

Table 1. Demographics, Health Status, Tobacco and ENDS Use Status, and Awareness of Tobacco Cessation Programs Among University Students, Faculty, and Staff for Survey Year 2017 and 2018

The proportion of current and former tobacco users was not significantly different for both 2017 and 2018. However, ENDS use significantly increased in 2018 (from 3.0% in 2017 to 4.1% in 2018). The proportion of respondents aware of tobacco cessation resources on campus and the Alaska Tobacco Quit Line did not significantly differ for both survey years. However, campus awareness of tobacco cessation resources was lower than awareness of the Alaska Tobacco Quit Line (see Table 1).

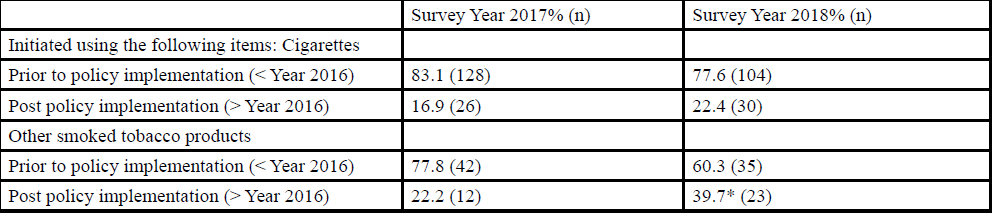

Tobacco and ENDS Initiation and Tobacco Cessation

Current tobacco users and current ENDS users were asked when they began using tobacco and ENDS products, respectively. Most of the current tobacco users in 2017 and 2018 began using tobacco prior to policy implementation (prior to year 2016). The current ENDS user situation, however, is different. While most current ENDS users in 2017 started using ENDS prior to policy implementation, by year 2018, most current ENDS users (71%) started using ENDS in 2016 and thereafter (when the policy has been implemented). With regards to tobacco cessation, when all of those who quit smoking cigarettes and other tobacco products, as well as those who quit using smokeless tobacco products were aggregated, there was a significant increase in tobacco cessation from 18% in 2017 to 24% in 2018. Note that none of the respondents in both survey years reported quitting use of ENDS. For more details, please see Table 2.

Table 2. Proportion of University Students, Faculty, and Staff Initiating Tobacco and E-Cigarette Use and Cessation Prior to and Post Policy Implementation for Survey Year 2017 and 2018

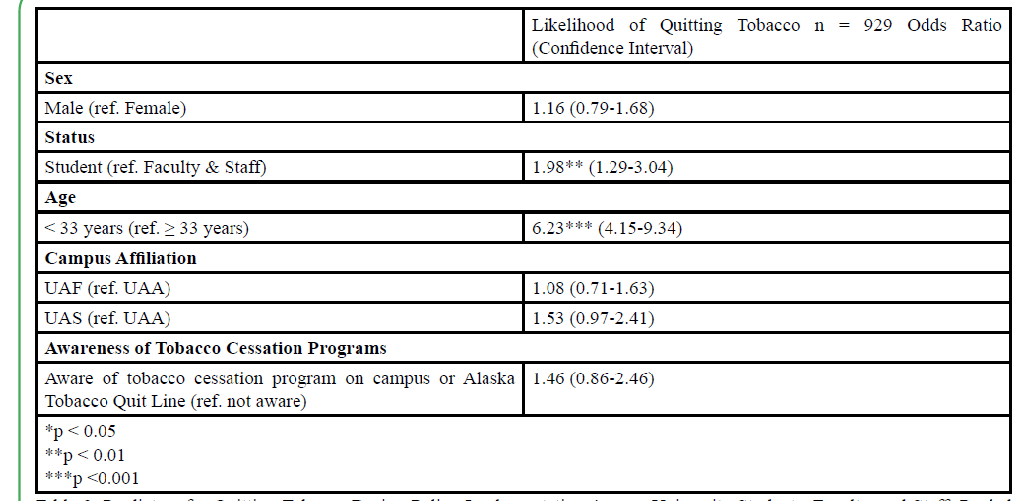

Factors Associated with Tobacco Cessation During Policy Implementation

Logistic regression was used to determine the demographic and awareness factors associated with quitting tobacco use during policy implementation by entering all the demographic and awareness factors altogether. Results show that students compared to faculty and staff had almost twice the odds of quitting during policy implementation. Additionally, those who are younger (less than 33 years old) had more than six times the odds of quitting tobacco during policy implementation compared to their older counterparts (see Table 3). The regression model has a good fit, having a nonsignificant Hosmer-Lemeshow test.

Table 3. Predictors for Quitting Tobacco During Policy Implementation Among University Students, Faculty, and Staff, Pooled Data from Survey Year 2017 and 2018

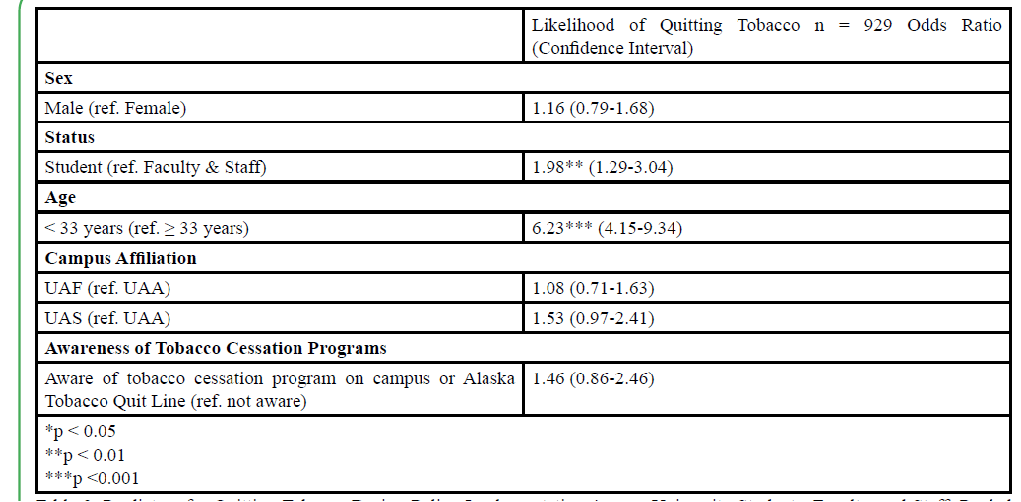

Factors Associated with ENDS use

Logistic regression was also ran to determine demographic factors and tobacco use status associated with ENDS by entering all the demographic factors and tobacco-related behaviors. Results show that males, students, and those who are younger had greater odds of ENDS use compared to their counterparts. In terms of tobacco use status, those who were current smokers and smokeless tobacco users were more likely to use ENDS compared to their non-tobacco using counterparts (see Table 4). The regression model has a good fit, having a non-significant Hosmer-Lemeshow test.

Discussion

Key Findings

Two of the rationales for having tobacco-free policy in college campuses are to prevent the initiation of tobacco use and to promote tobacco cessation among students, faculty, and staff [10]. However, empirical data to support these rationales are lacking, and this study attempts to address them. Unfortunately, this current study cannot completely confirm if the tobacco-free policy has prevented students, faculty, and staff from initiating tobacco use. What this study was able to show, however, is that less than 1 in 3 current tobacco users began using tobacco at the time when UA has already become tobacco free. Tobacco initiation, particularly cigarette smoking, typically occurs due to peer influence [11]. With the prohibition of tobacco use on campus, there is fewer to no opportunities for individuals to engage in tobacco socialization activities on campus and thereby fewer opportunities of choosing to initiate tobacco use on campus. Indeed, surveys conducted at UAA in 2017 show that almost 85% of students, faculty, and staff perceive that since policy implementation, there are fewer or no one is smoking or using tobacco on campus [12].

This study does provide some evidence that tobacco-free policy can potentially promote tobacco cessation among students, faculty, and staff. From 2017 to 2018, there was a significant increase in the proportion of current tobacco users at UA quitting post policy implementation. In terms of the factors significantly associated with tobacco cessation at post policy implementation, there were two: university status and age. Students and those who are younger (younger than 33 years old) are more likely to quit at post policy implementation compared to their counterparts. Unfortunately, this study does not have data that identifies the reason for this association, but it is possible that the reason for this could be that the policy has more effect on the students and those who are younger or perhaps that faculty and staff and those who are older are more resistant to changing their tobacco-related behaviors.

Finally, study findings suggest a growing popularity of ENDS among the UA community. Rates of ENDS use at UA campuses significantly increased from 2017 to 2018. However, rates of ENDS use at UA campuses are still lower than the statewide average (4% at UA vs. 5% Alaska statewide) [13]. Nonetheless, study findings suggest that the tobacco-free policy does not seem to have much of an effect on ENDS use. In 2018, 71% of the current ENDS user in UA campuses began using ENDS at the time the policy has already been in place. In terms of the factors associated with ENDS use among the UA community, this study found that males, students, those who are younger (< 33 years), and those who are current smokers of cigarette or other tobacco products are more likely to use ENDS. Given that smokers of cigarette or other tobacco products are more likely to use ENDS confirms previous findings that e-cigarette use are more likely to promote dual use, as opposed to promoting smoking cessation [14]. With an increasing number of individuals (both current smokers and nonsmokers) initiating ENDS use even with the policy prohibiting ENDS use suggests that perhaps individuals are choosing ENDS as their preferred smoking device on campus because it is easier for them to elude campus policy enforcers (in UA’s case, the university community) when smoking ENDS on campus given that after a few puffs of e-cigarettes or vapes, they could simply and quickly put their ENDS device in their pockets. In contrast, the process of smoking cigarettes takes more time, increasing the likelihood of the smoker being caught by the campus policy enforcer. In other words, for cigarette smokers, they would have to spend some time to finish smoking their cigarette before they get rid of it, risking being caught on campus for not complying with the policy.

Table 4. Predictors for ENDS Use Among University Students, Faculty, and Staff, Pooled Data from Survey Year 2017 and 2018

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, the surveys were selfreports, thus they were subject to social desirability bias. Upon implementation of the tobacco-free policy, survey respondents may feel more comfortable to report behaviors that are pro-tobacco-free policy. Moreover, biological measure (i.e., cotinine) were not used in this study to test if those reporting to be current smokers are actually smokers and the non-smokers are actually non-smokers. Related to problems with self-reports is recall bias. Respondents may not totally remember the exact age or year when they initiated or quit tobacco use.

Another limitation of this study is that it used a cross-sectional study design. Thus, the study is unable to make causal inference between the outcome variables and independent variables assessed in this study. Also, this study did not have a comparison school to serve as a control group nor did it have pre-policy data to compare with. Thus, the changes in tobacco-related behaviors reported by the survey respondents may not necessarily be changes caused by the tobaccofree policy. However, this study was at least able to establish the time when tobacco behaviors were initiated and terminated.

Finally, the study sample may not necessarily be generalizable to the entire student, faculty, and staff population of all the UA campuses. Although the sample for this study was randomly selected and that sufficient sample size was achieved for each survey year [9], the study only achieved around 25% response rate. While this is a low response rate, this is a much better response rate than previous university surveys. According to one university administrator, survey response rate is usually at around 15% when the administration has conducted university surveys in the past (University Administrator, e-mail correspondence). Moreover, this is the first study of its kind to include campus faculty and staff in the sample from the entire UA system.

Conclusions

Having a comprehensive campus tobacco-free policy can help promote tobacco cessation among students, faculty, and staff. It also appears to prevent students, faculty, and staff from taking up tobacco use. However, the campus tobacco-free policy does not seem to have much of an effect in preventing ENDS use, even if the policy includes the prohibition of ENDS. Thus, research is needed to understand the reasons students, faculty, and staff are using ENDS and what it would take to prevent the use of ENDS and promote ENDS cessation. Research is also needed to understand the role of enforcement and compliance in the prevention and cessation of tobacco and ENDS use.

Aknowledgements

This study was funded by the American Lung Association in Alaska. It has been approved by the University of Alaska Anchorage Institutional Review Board, IRB #: 862862-5.

All the authors were involved in the current study. Garcia was the Principal Investigator of the study. He conceptualized the study, managed data collection, analyzed the data, and wrote most of the manuscript. Mapaye was the Co-Principal Investigator of the study. She was involved in conceptualizing the study, co-managing data collection, writing parts of the manuscript, and reviewing and editing the manuscript. Roxbury helped collect data, conduct literature review, and wrote portions of the manuscript. Tabatabai-Yazdi helped manage and collect data, as well as review the manuscript. Lopez helped collect data, conduct literature review, and review the manuscript.

Conflict of interest:

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

References

American College Health Association [ACHA]. ACHA guidelines: position statement on tobacco on college and university campuses. ACHA. View

American Nonsmokers’ Rights Foundation [ANRF]. Smokefree and Tobacco-Free U.S. and Tribal Colleges and Universities. ANRF.View

Seo, D., Macy, J.T., Torabi, M.R., & Middlestadt, S.E. (2011). The effect of a smoke-free campus policy on college students’ smoking behaviors and attitudes. Prev Med 53(4-5): 347-352. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.07.015.View

Lechner, W.V., Meier, E., Miller, M.B., Wiener, J.L., Fils-Aime, Y. (2012). Changes in smoking prevalence, attitudes, and beliefs over 4 years following a campus-wide anti-tobacco intervention. J Am Coll Health 60: 505-511.View

Fallin, A., Roditis, M., & Glantz, S.A. (2015). Association of campus tobacco policies with secondhand smoke exposure, intention to smoke on campus, and attitudes about outdoor smoking restrictions. Am J Public Health 105(6): 1098-1100.View

Ickes M.J., Rayens, M.K., Wiggins, A., & Hahn, E.J. (2017) Students’ beliefs about and perceived effectiveness of a tobaccofree campus policy. Policy Polit Nurs Pract 18(1): 17-25.View

Lee, J.G.L., Ranney, L.M., & Goldstein, A.O. (2013). Cigarette butts near building entrances: What is the impact of smoke-free college campus policies? Tob Control 22(2): 107-112.View

Glassman, T.J., Reindl, D.M., & Whewell, A.T .(2011) Strategies for Implementing a Tobacco-Free Campus Policy. J Am Coll Health 59(8): 764-768.View

Raosoft, Inc. Sample size calculator. Raosoft, Inc. http://www. raosoft.com/samplesize.html. 2004; Accessed May 15, 2018.View

American Nonsmokers’ Rights Foundation [ANRF]. Model Policy for a Tobacco-Free College/University. ANRF. https:// no-smoke.org/wp-content/uploads/pdf/model-policy-for-atobacco- free-college-university.pdf. 2018; Accessed June 1, 2019.View

Varela, A., Pritchard, M.E. (2011). Peer Influence: Use of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Prescription Medications. J Am Coll Health 59(8): 751-756.View

Garcia, G.M., Mapaye, J.C., Roxbury, E., Delgado, V.L., & Tabatabai-Yazdi, N. (2018). Building a tobacco-free culture at a mid-size Public University Poster presented at: American Public Health Association Annual Meeting and Expo; San Diego, CA.

Alaska Department of Health and Social Services. Alaska Tobacco Facts: 2018 Update. http://dhss.alaska.gov/dph/ Chronic/Documents/Tobacco/PDF/2018_AKTobaccoFacts.pdf. 2018; Accessed June 2, 2019.

Glantz, S.A., Bareham, D.W. (2018). E-Cigarettes: Use, Effects on Smoking, Risks, and Policy Implications. Annu Rev Public Health 39(1): 215-235.View