Journal of Public Health Issues and Practices Volume 4 (2020), Article ID: JPHIP-162

https://doi.org/10.33790/jphip1100162Review Article

Gender in Context: A Multilevel Examination of the Effects of Structural Factors on Individual-Level Sentencing Decisions

Tina L. Freiburger

Department of Criminal Justice, University of Wisconsin--Milwaukee, P.O. Box 786, 1119 Enderis Hall, Milwaukee, WI 53201, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Tina L. Freiburger, Department of Criminal Justice, University of Wisconsin--Milwaukee, P.O. Box 786, 1119 Enderis Hall, Milwaukee, WI 53201, United States. E-mail: freiburg@uwm.edu

Received date: 29th January, 2020

Accepted date: 23rd April, 2020

Published date: 27th April, 2020

Citation: Freiburger, T.L. (2020). Gender in Context: A Multilevel Examination of the Effects of Structural Factors on Individual- Level Sentencing Decisions. J Pub Health Issue Pract 4(1):162.

Copyright: ©2020, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Abstract

The extant research has failed to consider how community factors affect women’s sentences. Drawing from the focal concerns perspective and feminist perspectives, the current study examines the possible influence that variations in gender equality at the community level have on the individual treatment of women in the court system. Using data from the Pennsylvania Sentencing Commission and United States Census Bureau, the results indicate that women are less likely to be incarcerated than men. This disparity was found to be smaller in areas with larger disparities in men and women income levels. Gender was not found to be significant for the sentence length decision, but a significant interaction between rate of married women in a community and gender was found, with women receiving longer sentences in areas with higher rates of married women. Theoretical and future research implications are further discussed.

One of the most prevalent findings in the sentencing literature is that gender is significantly related to sentence outcome [1,2]. This research has found that women are less likely to be incarcerated than men [2-9], and when incarcerated, typically receive sentences that are significantly shorter than their male counterparts [3-14]. Although gender disparity has received a great deal of attention at the individual level, prior research has not considered the possibility that the effects of gender could vary by community structure.

Research on community structure and sentencing has largely focused on racial and ethnic disparities that exist across communities. Although the findings of these studies are mixed, these inquiries indicate that in communities where racial minorities appear to be a greater threat, defendants are sentenced more severely (e.g., [15-17]. Despite the fact that women continue to experience gender discrimination and continue to be under represented in positions of power and influence, for example, women consist of half the population but makeup less than 20 percent of Congress, the extant research has failed to consider how community factors affect women’s sentences. The current study examines community structure and the possible influence that variations in gender equality at the community level have on the individual treatment of women in the court system.

Theoretical Perspective

A popular theoretical perspective used to explain gender disparity in sentencing is the focal concerns perspective. This perspective suggests that judges are concerned about three focal concerns when making sentencing decisions [2,18,19]. These concerns are dangerousness, blameworthiness, and practical constraints and concerns.Dangerousness is concerned with the threat that the offender poses to society and the likelihood that the offender will reoffend. Blameworthiness considers how culpable the offender was in the commission of his or her crimes. Practical constraints and concerns include organizational factors and individual characteristics of the defendant. Organizational factors include such things as available jail space and costs of incarceration. Individual factors are concerned with a defendant’s ability to serve his or her term of punishment, which can include such things as family responsibilities, community ties, and a defendant’s health.

According to focal concerns, these three concerns drive judges’ decisions as they attempt to allocate more severe sentences to defendants who are more blameworthy for their offenses, pose the greatest amount of danger to their communities and whose punishments pose the least amount of practical issues. When making sentencing decisions, however, judges often have limited information and time. Because of these limitations, the demographic characteristics of an offender are often used to shape the three focal concerns based on stereotypical images those demographic characteristics evoke. Certain demographic combinations, specifically, age, gender, and race, are especially influential, as judges tend to view younger minority men as more dangerous and more blameworthy, leading to harsher sentences for these individuals (e.g., [2,7,19,20].

For women, judges’ reduced perceptions of dangerousness and blameworthiness, and increased perceptions of practical constraints can be explained by other prior theoretical perspectives that address women’s position in society and society’s views and expectations of women. Chivalry and paternalistic theories argue that women are considered “softer” and more childlike than men. Because of this, society and court actors view women as in need of protection from the system and as less dangerous and less responsible for their actions (e.g., [18]).

Kruttschnitt (1982) and Kruttschnitt and Green (1984) further argued that women’s role in the family shapes perceptions of women. They assert that women are subjected to more informal control than men. This informal control stems largely from two sources. The first is women’s greater tendency to be economically dependent on another,either on their spouse or the state; the second source is due to the high level of supervision involved with being the fulltime caretaker of children. Because female family roles exert more control over women, the risks of women re-offending are viewed by judges as less than that of men and defendants without family. At the individual level, prior research has supported this argument, finding that judges are influenced by the level of informal social control to which women are subjected, and sentence women more leniently when informal controls are greater [21,23].

Other feminist theories have focused on how women who deviate from the traditional female role present a threat to a patriarchal society. The evil woman hypothesis argues that leniency is reserved only for women who meet the traditional female model. Women who do not conform to this model are subjected to harsher treatments, as they are being punished for not only their bad behavior but also for their deviation from their expected role [5] Bernstein et al., 1979;. While these perspectives have been used in the past to explain individual punishment decisions, they offer great insight into the community structural factors that could be expected to influence judges’ perceptions and stereotypes of women in general.

The focal concerns perspective also has been used to understand how structural characteristics can influence sentencing outcomes. According to Steffensmeier, Ulmer and Kramer (1998), judges are influenced by community pressures and consider organizational constraints when making sentencing decisions [19]. The communities in which courts are located vary economically and ideologically. The views and beliefs of community members also vary by court location. Given that courts are a part of the environment in which they are located, decisions made in the courts are believed to be influenced by community beliefs. Judges’ perceptions and stereotypes of offenders are heavily influenced by their community and surrounding environment. Specifically, it is possible that when inequality is great between men and women in a society, women are viewed as “traditional” and chivalry directs court actors’ decision making. In other words, women are viewed as less dangerous and blameworthy, and as presenting higher levels of practical constraints if removed from the family. As women become more equal to men in a community, however, they may be viewed more similarly to men in regard to the three focal concerns.

Literature Review

Structural Factors and Sentencing

Prior research has explored the relationship between county-level demographic factors and the punishment of criminal defendants. This body of research suggests that the social context in which sentencing decisions are made impact sentence outcome. Factors such as racial and ethnic composition of an area, rate of unemployment, political affiliations, and crime rate have been examined in these studies, and produced mixed findings in regard to the impact of structural factors [15,24-33].

Studies on how structural positions of power affects individual sentencing decisions has largely focused on race and the treatment of minorities. These studies have produced mixed results; but overall, indicate that the treatment of defendants is impacted by structural indicators of minority groups in a community (for exceptions see [31]). Myers and Talarico (1987) found that defendants had higher likelihoods of incarceration in areas where unemployment rates were higher. Black offenders also were punished more severely in areas with higher rates of unemployment and crime [16]. When racial income inequality was higher, sentence lengths decreased for all defendants. Britt (2000) also found that all defendants had a higher rate of incarceration in communities with larger Black populations [15]. Bontrager, Bales, and Chiricos’s (2005) examination of felony offenders in Florida further found that race and ethnicity effects varied by the percentage of minorities and the level of concentrated disadvantaged in a county [34].

More recently, Wang and Mears (2010) found that the size of the Black population and racial political threat increased the likelihood of defendants receiving a sentence to prison [17]. Felmeyer and Ulmer (2011) also examined the validity of the racial threat hypothesis in federal courts on the length of sentence received by Black and Hispanic defendants [35]. Their study found that minority populations only affected the treatment of Hispanics; Black defendants’ lengths of sentences did not vary by the number of Blacks in a community. The effect on Hispanics was in the opposite direction as expected, however, with Hispanics receiving the harshest sentences in communities with the smallest Hispanic population.

Prior research on the effects of structural factors has largely focused on how variables affect the treatment of minorities in comparison to Whites. Until now, research has not considered the possibility that the treatment of women in relation to men could vary by community structure. Specifically, this research examines how variations in male and women’s positions in the community impact the amount of social control that is exerted on women, and how the views of women might vary by indicators of structural equality.

Current Study and Hypotheses

The current study examines judges’ decisions to incarcerate defendants and the length of sentence given to defendants who are confined. Both individual and structural factors will be examined to determine the effect that gender has on individual sentences and how the effect of gender varies by structural factors. Prior research has consistently found that gender significantly impacts the sentencing process at both the in/out decision and the sentence length decision. Therefore, the first and second hypotheses state:

Hypothesis 1: Female defendants will be less likely to be incarcerated.

Hypothesis 2L Women will receive shorter sentences than male defendants.

Some measures used to assess minority’s position in a society, such as income and employment variations, also are useful in examining women’s positions in society. Other measures used to assess racial threat, however, should not be expected to be indicators of women’s position. Size of minority population is commonly used as an indicator of minority threat. Like racial minority groups, women are considered a less powerful group that is in need of control, however, women are not in the minority. Therefore, it is not reasonable to consider the number of women in a county as an indicator of female social controls. Instead of the number of women in relation to the number of men, a better indicator of the level of control exerted upon women is the percentage of married women in an area. Informal social control theory argues that women are viewed in less need of formal control when more informal controls are in place to regulate their behaviors. This is supported in previous research at the individual-level, which has found that married women are viewed as being subjected to greater amounts of informal social control and less in need of formal social control [21,22,36,37]. Based on these findings, the third and fourth hypotheses speculate that rates of marriage in a community will also influence perceptions of women at the individual-level. They state:

Hypothesis 3: Female defendants in areas with larger rates of married women will be less likely to be incarcerated and will receive shorter sentences than their female counterparts in areas with smaller rates of married women.

Hypothesis 4: Female defendants in areas with larger rates of married women will receive shorter sentences than their female counter parts in areas with smaller rates of married women.

Female’s income relative to men’s can also be an indicator of power in a society. According to Blalock’s (1967) minority threat perspective, when minorities achieve higher success in employment and income, they are viewed as a threat to Whites’ domination of the economic system [38]. This argument also applies to gender dominance, as men traditionally dominate the economic system. According to the Marxists feminist perspective, it is advantageous for men’s success in the capital market to have an unpaid worker in the home preforming domestic duties (e.g., caring for children, preparing meals). By entering the workforce, women are economically independent and create an alternative to being an unpaid worker in the home. In addition,as women progress into higher positions in the workforce, men no longer monopolize these positions, and instead, must now compete against women for their place of dominance [39,40]. Therefore, hypotheses five through eight focus on female employment and economic success in the workforce. They state:

Hypothesis 5: Female defendants in areas with greater differences in male and female income levels will be less likely to be incarcerated than their female counterparts in areas with less disparity in male and female income levels.

Hypothesis 6: Female defendants in areas with greater differences in male and female income levels will receive shorter sentences than their female counterparts in areas with less disparity in male and female income levels.

Hypothesis 7: Female defendants in areas with greater differences in male and female employment rates will be less likely to be incarcerated than their female counterparts in areas with less disparity in male and female employment rates.

Hypothesis 8: Female defendants in areas with greater differences in male and female employment rates will receive shorter sentences than their female counterparts in areas with less disparity in male and female employment rates.

Data and Methods

This study utilized individual sentencing data compiled by the Pennsylvania Commission of Sentencing (PCS) and structural data collected from the U.S. Census Bureau. The PCS individual data included offense, offender, and sentencing information for all defendants in 2006 and 2007 across the 67 counties in Pennsylvania. The data was limited to only include the most serious offense per judicial process. After cases with missing data were removed (2,438 cases), the final dataset contained 165,366 cases. Data from PCS contains a great deal of information on offense and offender characteristics, and has been used extensively in prior research on state court sentencing decisions (e.g., [28]). The U.S. Census Bureau data was collected for the 67 counties in Pennsylvania from the USA Counties database for 2007 and the 2000 summary files.

Dependent Variables

Following the general practice in the sentencing literature, this study examines the decision to incarcerate a defendant and the decision of sentence length as two separate and independent decision points. The decision to incarcerate is dichotomized to distinguish between a non-incarceration sentence (coded 0) and a sentence of incarceration in either jail or prison (coded 1). Other research has demonstrated a difference in the impacts of variables, such as race and ethnicity, on the decision to sentence defendants to jail or prison (see [6,41,[42]. Given the exploratory nature of the current study, this study uses the conventional measure of “in” as incarceration in either jail or prison. Findings of the current study, however, may be used to theorize possible differences in jail and prison for further inquiries. For sentence length, the minimum sentence length in months was examined. Due to this variable being positively skewed, this variable was transformed into the natural logarithm, which was used in the final analysis.

Individual-Level Variables

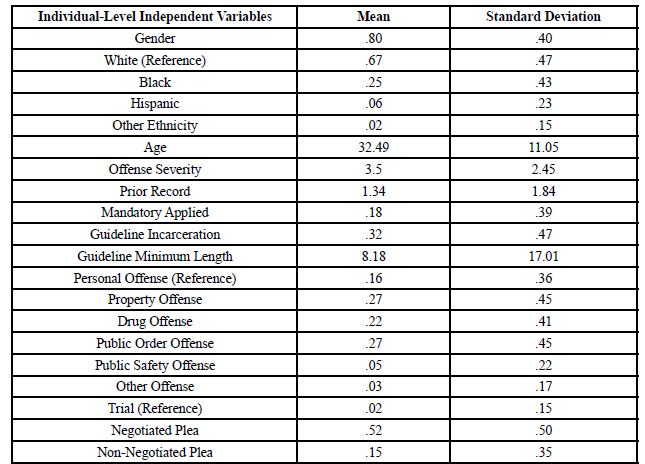

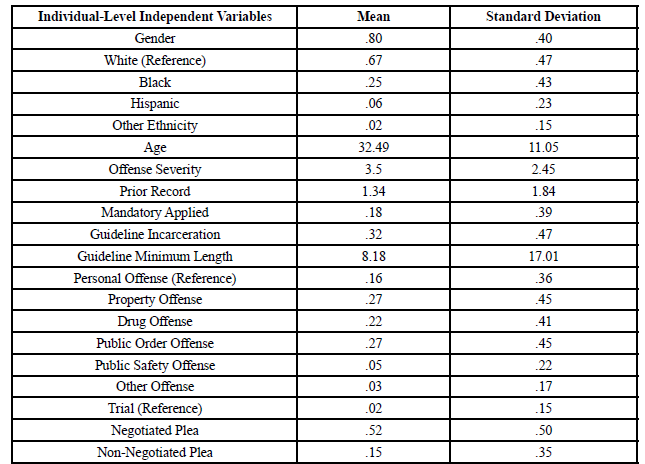

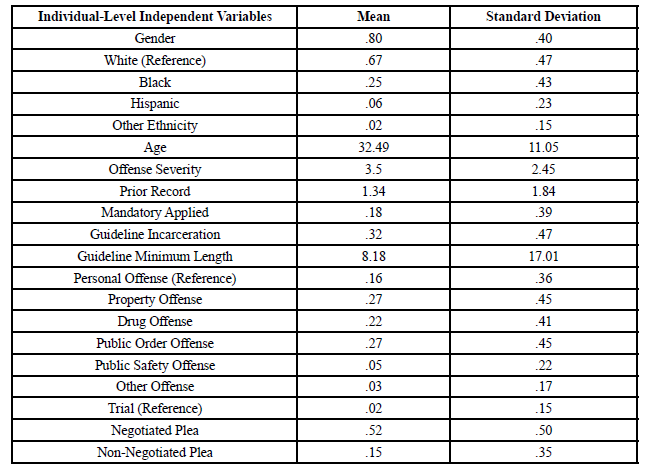

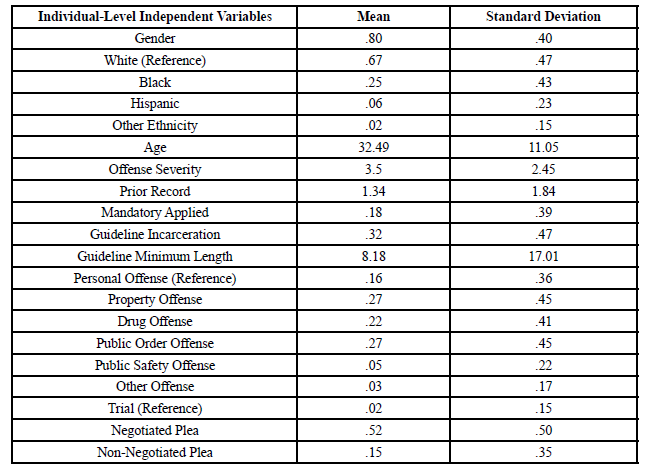

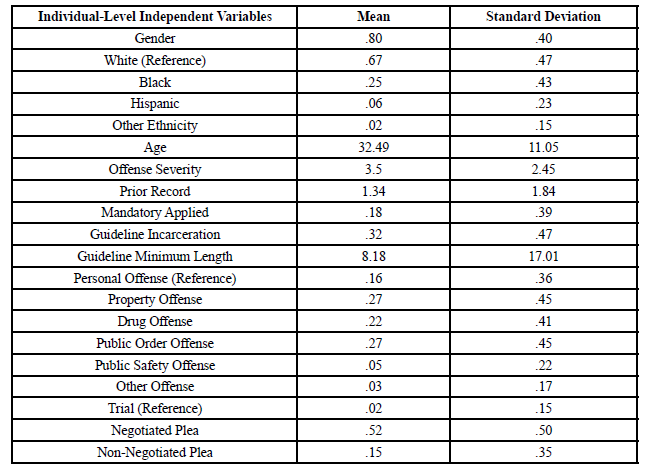

Several legal and extra legal variables that have been demonstrated in prior research as significantly impacting the sentencing decision were included in the analysis. The descriptive statistics for these variables is presented in Table 1. To control for offense severity, the offense gravity score was included. The offense gravity score is determined by a 14 point scale, which was included in the analysis. A defendant’s prior record was controlled using the prior record score which ranges from 0-7. Offense type was controlled with six dichotomous variables for personal offense (reference), property offense, drug offense, public safety offense, public order offense, or “other” offense. Type of conviction was controlled with four dichotomous variables for trial (reference), negotiated plea, non-negotiated plea, and other type of conviction.

The presumptive sentence prescribed by the guideline was included for the in/out decision to distinguish whether the guideline recommended a sentence of incarceration (0 = incarceration is not recommended and 1 = incarceration is recommended). For the sentence length decision, the number of minimum months recommended by the guideline was included. A variable was included to distinguish whether the mandatory sentence was applied. Year of sentence (1=2007) also was included as a control.

Several offender variables also were included. Gender was coded as 0 for women and 1 for men. Race was assessed using four dichotomous variables for White (reference), Black, Hispanic, and other ethnicity. Age was included as a continuous variable to represent the defendant’s age at sentencing. Because age has been found to be curvilinear in prior sentence research (e.g., [19,43]), a term was created by squaring each age and was included in the analysis. For the sentence length models, a selection bias estimate was created using the Heckman two-step method (1976), and was included in the analysis to correct for selection bias that could arise from only examining cases in which the defendant was sentenced to a term of incarceration [44].

Structural Variables

The structural variables of interest were measures collected to reflect women’s positions of power in a county. The descriptive statistics for these variables are presented in Table 1. Similar to prior studies examining racial equality (e.g., [15]), a variable was included to reflect the earnings of women in comparison to men in each community. This figure was obtained by subtracting the median income of women in that area from the median income of men. Because the value was positively skewed, the natural log transformation of this variable was used in the analysis. A variable for the difference in employment rates for men and women also was used as a measure to gauge male and female power variations in a community. This measure was calculated by subtracting the proportion of employed women in a community from the proportion of employed men in a community. Proportion of women in the county who were married also was included to assess women’s level of informal social control.

Population densities, percentage of Hispanics, and court sizes in a county have been found in prior research to affect sentencing decision; therefore, these variables were also included as control variables [27,28]. Court size was determined by dividing the number of cases heard in each court by the number of judges who decide cases in that court. Other variables were collected but were not included in the final models (percentage of Blacks, rates of violent crime, percentage of female headed households, and rate of divorce) due to problems with high collinearity.

Analytical Strategy

Because of the nesting structure of the data, hierarchical linear modeling was used. The two-level hierarchical model assessed the effects of individual-level defendant characteristics as well as the effects of community structural factors. Because the in/out decision was measured as a dichotomous variable, normality could not be assumed; therefore, hierarchical generalized linear models were estimated [45]. The sentence length variable was a continuous measure; therefore, hierarchical linear models were estimated. The analysis is presented in three stages. The first set of models addresses hypothesis one by examining the individual effect of gender on the incarceration decision and the sentence length decision. The next set of models examines the impact of the structural variables on both decision points. The final models address hypotheses two, three, and four by examining whether the gender equality variables intersect with gender to affect sentences.

Results

In all the models, all the individual-level variables were grand mean centered to reduce the estimation bias in the individual-level effect. Although it is possible that this technique can alter the parameter estimates and variance components associated with the intercept, additional analysis demonstrated that grand mean centering the variables did not significantly affect the results or conclusions [46].

Table 2 presents the individual-level model for the decision to incarcerate. The odds ratios indicate, that while controlling for county, with the exception of the three conviction variables (negotiated plea, non-negotiated plea, and other) all of the individual-level offender variables had a relatively strong impact on the incarceration decision, with mandatory applied having the greatest impact. With the exception of other race/ethnicity, the effects of all the independent variables varied significantly across counties. Similar to previous research, women were less likely to be incarcerated than men, with men having a 64% greater likelihood of receiving incarceration than women.

The same independent variables were entered into the sentence length model with the addition of a Heckman’s selection bias correction factor. The results for sentence length (shown in Table 3) indicate that gender did not significantly affect this decision point. In addition to gender, other ethnicity and the quadratic term for age were no longer significant at this decision point (similar to the incarceration model, the three methods of conviction variables also were not significant). With the exception of other ethnicity and other conviction type, the effects of all the independent variables varied significantly across counties.

Table 4 presents the results of the structural variables. Because the individual effects are similar to those presented in the previous models they are not presented for the sake of brevity (available from the author upon request). The results indicate that for the in/out decision none of the structural variables affected the incarceration decision. For the sentence length model, the size of the Hispanic population in an area and the population density of an area significantly impacted length of sentence defendants’ received. As the Hispanic population increased, sentence lengths also increased. Population density had the opposite effect, as the population density increased, the length of sentence decreased.

The results of the interaction model are presented in Table 5. Only one of the structural variables significantly interacted with gender for the in/out decision. The effect of this variable was not as predicted; in areas where a larger gap exists between male and female’s incomes, women were actually more likely to be incarcerated. For the sentence length decision, the interaction for percentage of women married and gender was marginally significant. Again, the effect was not in the predicted direction. As the percentage of married women in a county increased, the length of sentences for women slightly increased.

Discussion

This study examined how structural factors and community indicators of male and female equivalence in a society affects sentencing decisions. Using the focal concerns perspective and other feminist theoretical perspectives, it was predicted that as male and female inequality increased in a community, the sentence severity of women would decrease as views of women in these areas would be more consistent with the chivalry perspective. The results of the study are mixed, with only one hypothesis partially supported. Other findings, although unexpected, provide evidence that some gender disparity found in sentencing decisions may be determined by structural factors.

The first hypothesis that predicted that gender would have an individual effect on the in/out decision was supported. Consistent with prior research (e.g, [1-4,8]) women had lower odds of incarceration. Women did not, however, receive sentences significantly shorter than men. Although this is opposite than predicted, it is consistent with prior research finding that women did not receive sentences that were significantly shorter than men (e.g., [2,47-[52]), inconsistent with the second hypothesis. The second and third hypotheses, which predicted that female defendants would be sentenced more leniently in areas with larger rates of married women, was supported not supported. In fact, when examining sentence length, more married women in an area led to a slight increase in length of sentence for women. The fourth and fifth hypotheses predicted that female defendants would be sentenced more leniently in areas with greater differences in male and female income levels. These hypotheses were, again, not supported. For the incarceration decision, a larger gap in income meant an increase in women’ likelihood of being incarcerated. The six and seventh hypotheses, which predicted that female defendants would be sentenced more leniently in areas with greater differences in male and female employment rates, was not supported at either decision point.

From a feminist theory perspective, it is surprising that greater income disparities do not result in more severe sentences for women. Having a higher income and being able to support oneself and one’s family is a strong indication of power. Women who are financially self-reliant have an alternative to being an unpaid worker in the household. Women who commit crimes in these areas could be viewed as more dangerous; as women are more similar to their male counterparts in financial power, female criminals may be viewed as more equal to men in dangerousness and blameworthiness when they commit criminal offenses. Adler (1975) predicted that as women entered the workforce and achieved equality in the workforce, women would also achieve equality in the criminal environment [53]. Although women still offend at a rate much lower than men, one would expect that achieving equal (or near equal) workplace success would lead to court actors viewing criminal women as more equal to criminal men.

This is not the case, however, as women were actually less likely to be incarcerated in counties that were more equal. This might be an indication that as female power in an area increases (in the form of greater pay); women are in better positions to advocate for better treatment. It is possible that community-level gender disparity operates in a manner similar to community-level racial disparity. In that, when disparity increases, treatment of the disadvantaged group becomes harsher.

The finding of the rate of marriage in a county was also unexpected. Prior research suggests that, at an individual level, court officials view women who are married as less in need of formal control and more in compliance with traditional female roles. Because of this reduced informal control, their behaviors are viewed as in greater need of formal controls [21,22]. These findings, however, do not sustain at the aggregate level. Although only modestly significant, women in areas with high female marriage rates were sentenced to longer terms than women in areas with lower marriage rates. Although not hypothesized, this finding might also be explained with feminist perspectives of punishment. According to the evil women hypothesis, offending women can be viewed as more deserving of punishment due to their violations of their feminine role. Hence, in areas where women fill the traditional role of wife, violations of the female stereotype may be viewed less favorably leading to offending women in these areas being punished more harshly (or at least being granted less leniency) than women in other areas.

Limitations and Future Research

Research examining the effect of race relative to community structures has produced mixed findings. It is possible, therefore, that the same will be found for gender effects. To determine this, similar studies should be conducted in other areas. In addition, utilizing more diverse datasets might allow for larger variations of gender equality to be assessed. The individual data available was also limited. Specifically, measures of informal control and female’s position were not available at the individual level. Future research should examine how these factors affect the sentencing of women and how these effects vary by community indicators. It is possible that being unmarried will have different effects depending on the rate of women married in that area. Similarly, being employed might have a different affect for women in areas with higher levels of female employment than it would on women in areas with lower levels of female employment. It is further possible that characteristics of the judges (especially judge’s gender) affect how women are sentenced and how much influence community factors have on individual sentences [28,54]. Future research should consider a three level analysis, in which community factors are the third level and judge characteristics are the second level (similar to [28]).

It is important that research continue to consider the treatment of women and how perceptions of women impact their treatment. Future research should also explore the possibility that structural factors might differently influence women of different racial and ethnic backgrounds, as well as women of different social economic backgrounds. As prior research has demonstrated (e.g., [55-57]), not all women are treated the same. The effect of gender can vary by an individual’s race, ethnicity, demeanor, and family status. This varying effect of gender is indicative that gender is socially constructed and stereotypical images invoked by gender are dependent on other personal characteristics. Different groups also possess different expectations and perceptions of women. If the goal of punishment is to treated offenders equally, it is important to understand how these processes influence punishment disparities.

Thus far, research examining the effects of community structural variables on sentencing decisions has examined large groups (e.g., Black defendants, Hispanic defendants, and with this study, women) but has not further dissected these groups to explore the possibility that subgroups within these groups may be more or less affected by structural factors. The literature on sentencing at the individual level has produced more precise findings on the effects of gender, race/ ethnicity, and age by examining the intersections of these variables together, and has found that the effect of gender and age varies by a defendant’s race/ethnicity (e.g., [20,58,59]). It is possible that structural factors operate in a similar manner, and have different effects for defendants who better fit stereotypes of blameworthiness and dangerousness, such as young minorities, female minorities, or women of lower social classes.

Conflict of interest:

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

References

Spohn, C., & Beichner, D. (2000). Is preferential treatment of felony offenders a thing of the past? A multisite study of gender, race, and imprisonment. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 11(2), 149-184.View

Steffensmeier, D., Kramer, J., & Streifel C. (1993). Gender and imprisonment decisions. Criminology, 31(3), 411-446.View

Albonetti, C. A. (1997). Sentencing under the federal sentencing guidelines: Effects of defendant characteristics, guilty pleas and departures on sentencing outcomes for drug offenses, 1991- 1992. Law and Society Review, 31(4), 789-822.View

Blackwell, B.S., Holleran, D., & Finn, M.A. (2008). The impact of the Pennsylvania sentencing guidelines on sex differences in sentencing. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 24(4), 399-418.View

Farnworth, M., & Teske, Jr. R.H.C. (1995). Gender differences in felony court processing: Three hypothesis of disparity. Women & Criminal Justice, 6(2), 23-44.View

Freiburger, T.L., & Hilinski, C. (2013). The effects of race, gender and age on sentencing using a trichotomous dependent variable. Crime & Delinquency, 59(1), 69-86.View

Spohn, C., & Beichner, D. (2000). Is preferential treatment of felony offenders a thing of the past? A multisite study of gender, race, and imprisonment. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 11(2), 149-184.View

Spohn C., & Holleran, D. (2000). The imprisonment penalty paid by young unemployed black and Hispanic male offenders. Criminology, 38, 281-306View

Ulmer, J.T., & Kramer, J.H. (1996). Court communities under sentencing guidelines: Dilemmas of formal rationality and sentencing disparities. Criminology, 34, 383-407.View

Bushway, S.D., & Piehl, A.M. (2001). Judging judicial discretion: Legal factors and racial discrimination in sentencing. Law & Society Review, 35, 733-764.View

Huang, W.S., Finn, M.A., Ruback, R.B., & Friedmann, R.R. (1996). Individual and contextual influences on sentence lengths: Examining political conservatism. The Prison Journal, 76(4), 398-419.

Jeffries, S., Fletcher, G.J.O., & Newbold, G. (2003). Pathways to sex-based differentiation in criminal court sentencing. Criminology, 41(2), 329-353. View

Mustard, D.B. (2001). Racial, ethnic, and gender disparities in sentencing: Evidence from the U.S. Federal Courts. Journal of Law and Economics, 44, 285-313.View

Rodriguez, S.F., Curry, T.R., & Lee, G. (2006). Gender differences in criminal sentencing: Do effects vary across violent, property, and drug offenses. Social Science Quarterly, 87(2), 318-339.View

Britt, C.L. (2000). Social context and racial disparities in punishment decisions. Justice Quarterly, 17(4), 707-732.View

Myers, M. & Talarico, S. (1987). The social contexts of criminal sentencing. New York: Springer-Verlag. View

Wang, X. & Mears, D.P. (2010). A multilevel test of minority threat effects on sentencing. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 26, 191-215. View

Steffensmeier (1980). Assessing the impact of the women’s movement on sex-based differences in the handling of adult criminal defendants. Crime & Delinquency, 26(3), 344-358.

Steffensmeier, D., Ulmer, J. & Kramer, J. (1998). The interaction of race, gender, and age in criminal sentencing: The punishment cost of being young, black, and male. Criminology, 36(4), 763- 797. View

Steffensmeier, D. & Demuth, S. (2006). Does gender modify the effects of race-ethnicity on criminal sanctioning? Sentences for male and female White, Black and Hispanic defendants. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 22, 241-261. View

Daly, K. (1987). Discrimination in the criminal courts: family, gender, and the problem of equal treatment. Social Forces, 66(1), 152-175. View

Daly, K. (1989). Neither conflict for labeling nor paternalism will suffice: Intersections of race, ethnicity, gender, and family in criminal court decisions Crime and Delinquency, 35, 136-168. View

Freiburger, T.L. (2011). The impact of gender, offense type, and familial role on the decision to incarcerate. Social Justice Research, 24(2), 143-167. View

Fearn, N.E. (2005). A multilevel analysis of community effects on criminal sentencing. Justice Quarterly, 22(4), 452-487. View

Helms, R. & Jacobs, D. (2002). The political context of sentencing: An analysis of community and individual determinants. Social Forces, 81(2), 577-604.View

Johnson, B.D. (2003). Racial and ethnic disparities in sentencing departures across modes of conviction. Criminology, 41(2), 449-490.View

Johnson, B.D. (2005). Contextual disparities in guideline departures: courtroom social contexts, guidelines compliance disparities in criminal sentencing. Criminology, 43(3), 761-796.View

Johnson, B.D. (2006). The multilevel context of criminal sentencing: Integrating judge- and county-level influences. Criminology, 44(2), 259-298.View

Johnson, B.D., Ulmer, J.T. & Kramer, J.H. (2008). The social context of guidelines circumvention: The case of federal district courts. Criminology, 46(3), 737-783.View

Kautt, P. M. (2002). Location, location, location: Interdistrict and intercircuit variation in sentencing outcomes for federal drug-trafficking offenses. Justice Quarterly, 19(4), 633-671.View

Ulmer, J.T. & Johnson, B. (2004). Sentencing in context: A multilevel analysis. Criminology, 42(1), 137-177.View

Weidner, R.R., Frase, R. & Pardoe, I. (2004). Explaining sentence severity in large urban counties: A multilevel analysis of contextual and case-level factors. The Prison Journal, 84(2), 184-207.View

Weidner, R.R., Frase, R. & Schultz, J.S. (2005). The impact of contextual factors on the decision to imprison in large urban jurisdictions: A multilevel analysis. Crime and Delinquency, 51(3), 400-424.View

Bontrager, S., Bales, W. & Chiricos, T. (2005). Race, ethnicity, threat and the labeling of convicted felons. Criminology, 43(3), 589-622.View

Feldmeyer, B. & Ulmer, J.T. (2011). Racial/ethnic threat and federal sentencing. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 48(2), 238-270.View

Kruttschnitt C. (1982). Women, crime and dependency: an application of the theory of law. Criminology, 19, 495-513.View

Kruttschnitt C. & Green D. E. (1984). The sex-sanctioning issue: is it history? American Sociology Review, 49, 541-551.View

Blalock, H.M. (1967). Toward a minority-group relations. New York: Capricorn Books.View

Benston, M. (1969). The political economy of women's liberation”, Monthly Review, 21 (4), 11-25.View

Fox, B. (1980). Hidden in the Household: Women's Domestic Labour under Capitalism, Toronto: The Women's Press.

Harrington, M.P. & Spohn, C. (2007). Defining sentence type: Further evidence against use of the total incarceration variable. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 44(1), 36-63.View

Holleran, D. & Spohn, C. (2004). On the use of the total incarceration variable in sentencing research. Criminology 42(1), 211-40.View

Steffensmeier, D. & Kramer, J.H., (1995). Age differences in sentencing. Justice Quarterly, 12, 701-719.View

Heckman, J. (1976). The common structure of statistical models in truncation, sample selection and limited dependent variables. Annuals of Economic and Social Measurements, 5, 472-492.View

Radenbush, S., Bryk, A., Cheong, Y.F., Congdon & Toit, M. (2004). HLM6: Hierarchical linear and nonlinear modeling. Lincolnwood, IL: SSI Scientific Software International.

Luke, D.A. (2004). Multilevel modeling. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.View

Crew, B.K. (1991). Sex differences in criminal sentences: Chivalry or patriarchy? Justice Quarterly, 8(1), 59-83.View

Green, P. Mills, C. & Read, T. (1994). The characteristics and sentencing of illegal drug importers. British Journal of Criminology, 34(4), 479-487.

Harper, R.L., Harper, G.C. & Stockdale, J.E. (2000). The role of sentencing of women in drug trafficking crime. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 7(1), 101-115.

Nobling, T., Spohn, C., DeLone, M. (1998). A tale of two counties: Unemployment and sentence severity, Justice Quarterly 15, 459-486.View

Wheeler, S., Weisburd, D., & Bode, N. (1982). Sentencing the white-collar offender: Rhetoric and reality. American Sociological Review, 47, 641-659.View

Zatz, M.S. (1984). Race, ethnicity and determinate sentencing: A new dimension to an old controversy. Criminology, 22, 147- 171.View

Adler, F. (1975). Sisters in crime: The rise of the new female criminal. New York: McGraw Hill.View

Steffensmeier, D. & Britt, C.L. (2001). Judges’ race and judicial decision making: Do black judges sentence differently? Social Science Quarterly, 82(4), 749-764.View

Chesney-Lind, M. (1982). Guilty by reason of sex: Young women and the juvenile justice system. In B. R. Price & N. J. Sokoloff (Eds.), The criminal justice system and women: Offenders, victims, workers (pp. 77-103). New York, NY: McGraw Hill.

Dodge, M. L. (2002). Whores and thieves of the worst kind: A study of women, crime and prisons (1835-2000). Dekalb, IA: Northern Illinois University Press.View

Seitz, T. N. (2005). The wounds of savagery: Negro primitivism, gender parity, and the execution of Rosanna Philips. Women & Criminal Justice, 16, 29-64.

Freiburger, T.L. & Hilinski, C. (2010). The impact of race, gender, and age on the pretrial decision. Criminal Justice Review, 35(3), 318-334.View

Spohn, C. (2013). The effects of the offender’s race, ethnicity, and sex on federal sentencing outcomes in the guidelines era. Law and Contemporary Problems, 76(75), 75-104.View