Journal of Public Health Issues and Practices Volume 4 (2020), Article ID: JPHIP-164

https://doi.org/10.33790/jphip1100164Review Article

In Search of Behavior Change: Cognitive Restructuring Techniques for Increasing Self Efficacy in Older Adults and Physical Activity

Keri Diez Larsen*, Alice B Gibson

Department of Kinesiology and Health Studies, Southeastern Louisiana University, SLU Box 10845, Hammond, LA 70402, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Dr. Keri Diez Larsen, Department of Kinesiology and Health Studies, Southeastern Louisiana University, SLU Box 10845, Hammond, LA 70402, United States. E-mail: keri.larsen@selu.edu

Received date: 21st February, 2020

Accepted date: 09th May, 2020

Published date: 12th May, 2020

Citation: Larsen, K.D., & Gibson, A.B. (2020). In Search of Behavior Change: Cognitive RestructuringTechniques for Increasing Self Efficacy in Older Adults and Physical Activity. J Pub Health Issue Pract 4(1):164. doi: https://doi.org/10.33790/ jphip1100164.

Copyright: ©2020, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Abstract

The ability of health educators, exercise specialists and other health-related professionals to foster participation in physical activity in older adults has been a challenge for many years. Many health professionals have endeavored to develop programs to encourage behavior change in this population, without much success. Most of the programs have avoided the issue of self-efficacy. The purpose of this review is to examine the use of cognitive restructuring as a psycho-educational intervention for behavior change.

This review defines physical activity and exercise, the benefits of physical activity and exercise for older adults, the psychological benefits, the recommended levels of physical activity and exercise for older adults and the current level of physical activity trends and exercise for older adults. It also presents an overview of several behavior change theories along with a detailed review of the selected change theory, Social Cognitive Theory. Finally, factors affecting development of an intervention designed to result in behavior change in regard to physical activity/exercise will be reviewed.

Physical activity has been shown to be advantageous to individuals, regardless of their particular stage in life [1]. More specifically, exercise has been shown to have positive effects on the health of individuals from childhood through individuals in their 80's and beyond [1]. In fact, research indicates that there is no defined age at which individuals stop receiving health benefits from exercise or physical activity [1,2].

In contrast, physical inactivity is one of the major health risks for people of all ages [2]. Moreover, physical inactivity has been selected as the leading health indicator in the Healthy People 2020, which is a set of federal health objectives for the nation to achieve over the first decade of the new century. This program reflects the commitment of the federal government to promoting the health of the U.S. population. The most recent plan has two goals for Americans through the year 2020: increasing the quality and years of healthy life and eliminating health disparities.

Physical Activity and Exercise Defined

According to the World Health Organization, the definition of physical activity includes any movement in everyday life, including work, recreation, exercise, gardening and sporting activities that burn calories. Exercise is described as structured and organized movement of the body [1]. A structured exercise regime is a component of physical activity, which is a much broader term that includes all aspects of a lifestyle that incorporate movement. Light intensity physical activity is physical activity that is performed below 60 percent of maximum heart rate. Moderate intensity physical activity is physical activity that is performed at 60-70 percent of maximum heart rate. Vigorous intensity physical activity is physical activity that is performed at 70 – 85 percent of maximum heart rate [1,3].

Benefits of Physical Activity and Exercise

Although the definitions of exercise and physical activity are distinct, research documenting the physiological benefits of the two have sometimes blurred the distinction. For the purpose of this review, the discussion of the physiological benefits was divided into three distinct categories, exercise-related studies and physical activity-related studies, along with a category for a combination of the two, exercise and physical activity-related studies. The review of psychological studies used only a combined category.

Exercise-Related Studies

Studies have found that older adults who participate in regular exercise have exhibited some of the following benefits: weight management, reduced risk of osteoporosis and diabetes, improvements in perceived health, functional status, mobility and reduced risk of institutionalization, reduced risk of cardiovascular disease and increased longevity [4-6]. Research has shown that there are many physiological benefits of exercise to people of all ages, especially the older population [7].

Regular exercise training reduces the risks of cardiovascular and age-associated diseases [6]. Furthermore, strength training is very important for older adults because it helps slow down the loss of muscle mass that begins in the mid 30’s, which decreases an individual’s strength [7]. This decrease in strength can impact an older adult’s ability to remain functionally independent, and put them at much greater risk for falls and other debilitating injuries [7,8].

One significant factor that affects older persons, particularly postmenopausal women, is osteoporosis. Osteoporosis is a disease in which the bones become extremely porous. Without exercise, bones become increasingly weak with age and can leave an older adult susceptible to fractures [9-11]. This disease occurs predominantly in women following menopause and often leads to severe curvature of the spine due to vertebral collapse [11,12]. Current evidence suggests that exercise slows the rate of bone loss [2,9,11].

Physical Activity-Related Studies

According to the United States Surgeon General’s Report regular physical activity has important positive effects on the musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, respiratory and endocrine systems [12]. Physical activity has been found to contribute to better health, improved fitness, better posture and balance, better self-esteem, weight control, stronger muscles and bones, feeling more energetic, relaxation and reduced stress, and continued independent living in later life [1,7,13,14].

Conversely, physical inactivity is associated with increased health risks for individuals. The health risks of inactivity include premature death, heart disease, obesity, high blood pressure, adult-onset diabetes, osteoporosis, stroke, depression, and colon cancer [7,13].

The importance of physical activity or exercise is extraordinary, not only for the young or athletic, but for the old and aging especially with regard to longevity and a healthy life. Middle-aged men who have been habitually active or become active are more likely to reach old age than if they are sedentary [2,15]. According to the CDC’s National Vital Statistics Report the average life expectancy of American men at age 65 was approximately 18 years and American women at age 65 was approximately 20.6 years, but the more physically active these men and women seem to be, the more their expected lifespan increased over their sedentary counterpart [16]. Studies have shown that a more physically active lifestyle or a greater capacity for exercise is associated with a lower mean arterial blood pressure and a lower prevalence of hypertension in older men and women thus indicating better overall health of the elderly individual [7].

Psychological Benefits of Physical Activity and Exercise

Research shows that physical activity and/or exercise is equally important within the psychological realm of the older individual as it is in the physical realm [7,14]. It is also important to note that the psychological benefits are not dependent on the particular types of activities undertaken.

Participation in regular physical activity has been shown to reduce depression, anxiety and stress, improve mood, and create opportunities for social interactions [12,16]. Studies have found that exercise is as effective as other forms of psychotherapy on depression and seems to have an antidepressant effect on individuals with mild to moderate diagnoses of depression [17]. More than 15 million Americans are affected with symptoms of depression each year [18]. Although there are a number of reasons older adults experience a decline in life satisfaction such as loss of a spouse and forced leisure time, the absence of any type of physical activity and/or exercise may account for some changes noted in the life satisfaction of older adults [19].

Research has found that an increase in activity level increases life satisfaction in the older individual [7,19]. Toseland and Sykes found that one of the most important predictors of life satisfaction was activity level [20]. Ruuskanen & Ruoppila and ACSM also found that while an increase in activity increases life satisfaction of the older person, psychological well-being is an important factor in predicting adherence to physical training at advanced ages [7,21].

Given the illustrated importance of exercise and/or physical activity on counteracting the symptoms of depression along with the documented benefits of exercise and/or physical activity on overall life satisfaction and self-esteem for older adults physical activity and/ or exercise should be an important part of every individual’s life, regardless of age [21].

Recommended Levels of Physical Activity and Exercise

According to the federal guidelines for physical activity, Healthy People 2020, recommends an “increase to at least 30% the proportion of people aged 6 and older who engage regularly, preferably daily, in light to moderate physical activity for at least 30 minutes per day” [1,2,22]. Other exercise recommendations for older adults include at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity throughout the week and in increments of 10 minutes at a time [23]. The World Health Organization states that physical activity for older adults can include leisure time activities such as dancing, gardening, walking, chores, sport, planned exercise and a variety of others [23].

In the past few years, a new way to regard the recommended level of physical activity and/or exercise necessary for older adults has surfaced [1]. There is accumulating evidence that some physical activity, even in small increments of time, is better than no physical activity [1]. According to the US Surgeon General’s Report on Physical Activity and Health, older adults can obtain significant health benefits with a moderate amount (about 30 minutes) of physical activity, preferably daily [12]. According to the US Surgeon General, regular physical activity that is performed on most days of the week reduces the risk of developing some illness and even reduces the rate of death from some types of cancer [12].

Studies have shown that moderate exercise or physical activity, at least half an hour for three times a week is an important aid in controlling weight, keeping bones strong, building muscle strength, conditioning the heart and lungs and relieving stress [2,12,21]. Also, older adults who were previously sedentary and are beginning a physical activity or exercise program should start with short intervals of moderate physical activity (5-10 minutes) and gradually build up to the desired amount as prescribed by their physician [12]. All individuals should consult with a physician before beginning a new physical activity program [12]. Considering the extraordinary benefits of staying active, it is important to consider how many older adults actually participate in physical activity or exercise at any level?

Current Level of Physical Activity and Exercise Levels

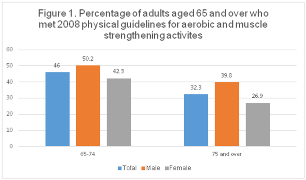

According to Healthy People 2020, by the time adults reach age 75, only one in three men and one in two women engage in regular physical activity and/or exercise [2]. According to the National Center for Health Statistics, 32.3% of adults aged 75 and over performed the recommended amount of physical activity. Figure 1 refers to the illustration of this information [24]. The key concern here is why do older adults not participate in regular physical activity and/or exercise?

Barriers to Physical Activity and Exercise

According to O’Neill & Reid, perceived barriers are the potential negative aspects of a particular health action that may act as a deterrent for undertaking a recommended health promotion behavior [25]. O’Neill and Reid postulate that there are four specific types of perceived barriers to exercise and/or physical activity for older adults: psychological, administrative, physical/health and knowledge [25]. O’Brien Cousins expands the psychological categories to specify four barriers: beliefs about coming to physical harm, beliefs about experiencing negative social outcomes, beliefs regarding negative psychological consequences and other beliefs related to the environment or nature of the activity [9].

Bandura stipulated that the psychological barriers to exercise and/ or physical activity are the most important type of perceived barriers to examine when trying to understand why older adults do not participate in exercise and/or physical activity [26]. O’Brien Cousins concurs with this finding [9]. She found that the main barriers to participation in late-life exercise and/or physical activity are psychological in nature and centered on negative attitudes, feeling foolish, and feeling inferior to other participants [7,9].

Psychological barriers might be formidable obstacles to undertaking activities documented to promote health. O’Brien Cousins found that there is “a conscious resistance to fitness activity in later life even though most older adults agree that physical exercise is “good for you’” [9].

Many older adults believe that they should not participate in any type of physical activity because they are too old and may be injured [25,27]. It is also believed that regular exercise would serve no purpose for them because their body is beyond repair [28]. Some older adults are not aware of the benefits of exercise and/or physical activity and some do not think that they are able to perform the exercises to receive the benefits [29]. These attitudes regarding their involvement in exercise (self-efficacy) construct barriers to their participation and undermine their sense of self-efficacy [30].

It is important to consider whether or not older adults refrain from participating in any type of exercise or physical activity because they believe they are too old, or they are afraid of possible injuries, or they do not believe they can perform any type of physical activity because it helps illustrate the importance of psychological barriers in explaining why older adults are sedentary. Furthermore, sufficient evidence suggests that self-efficacy in regard to physical activity is key to why many older adults are not even attempting to participate [29,30].

There are several theories that have been applied to older adults and regular physical activity or exercise. Each model presented has been researched and their characteristics compared in order to determine the most appropriate method for increasing self-efficacy of older adults regarding exercise and/or physical activity.

Developing a Framework for Theoretically-Based Curriculum Materials Theoretical Overview

The Health Belief Model, Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Change, Theory of Reasoned Action, Locus of Control, and Social Cognitive Theory (formerly known as Social Learning Theory) have all been applied to the problems of explaining, predicting and changing behavior [31]. In one way or another, these models have similar elements and/or foci; therefore, some overlap is expected when examining them for the purpose of developing a sound theoretically based intervention to influence behavior.

Health Belief Model

Within the Health Belief Model three factors must be present for a health-related action to occur. First of all, there must be sufficient motivation present to make that particular healthrelated action seem relevant. Second, the individual must believe that they are susceptible to a serious health problem or illness. Third, the individual must believe that implementing or carrying out a particular health-related behavior or behavior change would actually reduce the risk of that perceived threat [32].

In other words, an older adult who has a heart condition and has no physical activity in his/her daily lifestyle must believe that inactivity is potentially harmful to their health. Then, they must believe that they are personally vulnerable to a heart attack. And finally, they must believe that they will be able to reduce their risk of a heart attack and/or death by the initiation of an exercise regime. These things must take place for behavior change to occur.

Transtheoretical Model

The Transtheoretical Model of behavior change has been used extensively to promote optimal health by promoting behavioral change in the areas such as smoking, diet, alcohol and substance abuse, eating disorders, panic disorders, and others [33].

This model is all-encompassing in that it attempts to evaluate, predict and explain behavior [33]. The main component of this theory postulates that change occurs gradually and is a result of the actual behavior as well as the intention [33].

According to the theory, change occurs in discrete stages beginning with the pre-contemplation stage, which is the period of time before a person recognizes that a health problem exists. The next stage is the contemplation stage, during which an individual realizes a problem exists and contemplates a change. Then, the preparation stage occurs, a stage in which planning for a particular behavior change occurs. The preparation stage is followed by the action stage, which is the actual carrying out of the behavior change. Finally, the maintenance stage is the stage during which an individual works and attempts to maintain the newly acquired behavior change.

It is possible that the stage the person is in (i.e. contemplation, action, maintenance) is related to their efficacy level at that time [34]. It appears that a person’s exercise efficacy could be related to their previous attempts at this behavior. In developing interventions for behavior change, identifying the stages that your participants are in is the first step because the different stages imply that different types of interventions are needed to be successful.

Self-efficacy is an important component of the Stages of Change and necessary for movement from one stage to another [33,35]. There seems to be a very clear relationship between self-efficacy and progression toward behavior change [36]. It appears that self-efficacy is lowest in the precontemplation stage when one does not realize the need for change and highest in maintenance where one has made a behavior change and is trying to sustain that change [34]. So, to encourage a person’s progression through the stages, self-efficacy needs to be increased [34]. However, some may argue that selfefficacy is a by-product of successful movement through the stages.

Theory of Reasoned Action

The Theory of Reasoned Action was developed by Izek Ajzen and Martin Fishbein and is significant because it focuses on the prediction of behavior performance [37]. This theory could be beneficial to health workers when trying to promote behavior change (i.e. implementation of exercise program). This model was designed to predict behavior based on a number of factors. These factors include attitude, social influence, and intention [37]. According to this theory, a person’s intention regarding a particular behavior is the likelihood that they will perform that behavior. Ajzen and Fishbein postulated that an individual’s intention to perform a particular behavior is determined by their attitude about the performance and whether or not that individual believes others think that he/she should perform that particular behavior [37].

An attitude is a person’s belief that is associated with performing a particular behavior. A belief may be positive or negative. Fishbein and Ajzen state that a positive attitude toward performing a particular behavior will be present if the person believes that the performance will lead to positive outcomes [38]. They also state that a negative attitude about performing a particular behavior will be present if that person believes that the performance will lead to negative outcomes [38]. In other words, if a person believes he/she will receive many health benefits from exercising, then he/she will have a positive attitude about performing that behavior. Or, if a person believes that he/she will probably be injured if they exercise, then he/she will have a negative attitude about exercising.

According to Fishbein and Ajzen, subjective norms are the beliefs about whether or not others think they should or should not perform that particular behavior. These subjective norms are also an indication about whether he/she will actually perform that behavior [38]. An example of a subjective norm is a person’s belief that medical professionals do not want them to exercise; therefore resulting in a negative subjective norm, thereby negatively impacting the goal of increasing self-efficacy.

Locus of Control

According to Rotter, locus of control refers to the amount or degree of control the individual believes they have over particular events (internal control) compared to the degree of control that the individual believes resides in external forces (external control) [39]. The theory put forth by Rotter is one of the best known and most thoroughly researched in the area of personal control [39]. When a person is said to have an internal locus of control, they hold the belief that they control the outcome of their own life. People with an internal locus of control usually face problems head on, think that something can be done to work through problems and take responsibility for what happens to them. The person with an external locus of control has the perception that the control and responsibility of outcomes in their life is beyond their control, either by luck, chance, fate, or other people. This type of person usually feels powerless when faced with a dilemma because they think they have no control over their own destiny.

If a person has an internal locus of control and is confronted with the increased likelihood of a heart attack because of physical inactivity, then he/she is likely to believe that he/she can control his/her destiny or outcome and may start exercising to offset the risk. Conversely, if a person has an external locus of control, then when faced with the possibility of a heart attack, he/she is likely to say that his/her fate is not in his/her hands and probably will not take an action such as exercising. Locus of control has been distinguished from selfefficacy, in that locus of control is the control over particular events [39] and self-efficacy is one’s belief about their performance of an action [40].

Social Cognitive Theory

Bandura presented a theory of social development that has been used as a method of influencing individuals to make behavior changes such as implementing exercise or physical activity into one’s lifestyle [27]. Social Cognitive Theory provides specific concepts that influence motivation to adopt a behavior such as physical activity [41].

More specifically, Bandura's theory of social development centers on how people cognitively perceive their social experiences and how these cognitive perceptions influence their behavior and their development [42]. Individuals process information that is gathered from their social experiences. Through this processing of information, individuals categorize their cognitions, and use their cognitions to determine responses to their environment and the type of environment they search out for themselves [43]. This theory is now referred to as Social Cognitive Theory.

Bandura argues that individuals are motivated to act in specific ways depending upon whether or not they believe the action will be beneficial to them. This process is labeled outcome expectancy [44]. Also, individuals must believe that they can perform the intended behavior. The magnitude of their belief in performance is their level of self-efficacy for a task.

According to Social Cognitive Theory, the motivation of individuals to act is largely controlled by their thoughts. This control device involves three different types of expectancies: (1) situationoutcome expectancies - the consequences of an action are cued by environmental events without personal action, (2) action-outcome expectancies - outcomes are derived from personal action, and (3) perceived self-efficacy - the beliefs an individual possesses about their own ability to perform an action to gain the desired outcome [27].

Self-efficacy is defined as a judgment of a person’s capability to accomplish a certain level of performance [41]. The concept of selfefficacy suggests that individuals develop specific beliefs about their own abilities that direct their behavior in terms of which things they try to achieve and the amount of effort they put forth in that particular area [27]. Basically, a person’s perceptions determine how he/she judges information that is gathered from his/her social environment. For instance, if a person has a negative self-perception about a particular situation, and lacks the ability to perform well in that situation, then his/her self-perceptions detour he/she from pursuing and accomplishing that particular activity.

Furthermore, if an individual has a positive self-perception about a situation, he/she is more likely to believe he/she can successfully attempt and complete an activity; thus, he/she puts forth the effort and is more likely to succeed. In effect, his/her perception about a situation plays a large role in whether an activity is completed and possibly if that activity is even attempted.

Self-efficacy affects how people feel, act and think [41]. Low selfefficacy has been associated with anxiety and depression, low selfesteem and negative ideas about personal accomplishments [45]. Those individuals who possess a high self-efficacy are more likely to have a strong sense of competence in regard to their accomplishments and in effect, they choose to attempt more tasks than those with low self-efficacy. Individuals with higher self-efficacy are more likely to set higher goals and are also more likely to bring their goals to fruition than those who possess low self-efficacy [45]. The key component of Bandura's Social Cognitive Theory and the theoretical framework that will be focused on in this paper is the perceived self-efficacy in the context of cognitive behavior modification in terms of exercise or physical activity.

Self-Efficacy

Bandura introduced the concept of perceived selfefficacy in the context of cognitive behavior modification and it has been found that a strong sense of personal efficacy is related to better health, greater social integration, and higher achievement [27, 45]. This concept has become a key component in educational, social, clinical, developmental, health and personality psychology.

Self-efficacy plays an important role in how people think, feel, and act. A person’s level of self-efficacy can enhance or impede their motivation to act [46]. If a person has a strong sense of competence, his/her cognitive processes are elevated and consequently, so are his/her performance, both physically and academically [27]. People who have a low sense of self-efficacy are more prone to depression, anxiety, low self-esteem and harboring pessimistic thoughts about their personal accomplishments, achievements and development [27].

In contrast, individuals with a high level of self-efficacy set higher goals for themselves and they choose to perform more challenging tasks [47]. An individual’s actions are pre-formed in their thought processes, and whether that individual anticipates an optimistic or pessimistic outcome is related to their level of self-efficacy [27]. Once the action is undertaken, a person with a high level of selfefficacy will invest more time and effort in their commitment to the activity [27].

Furthermore, when setbacks occur, the person that is highly selfefficacious will recover more quickly and redirect his/her energies to his/her commitment. Self-efficacy is not based on illusions that are unrealistic, but on personal experience. And, it does not lead to risk taking, but adopting healthier behaviors and refraining from healthimpairing behaviors [48].

Perceived self-efficacy embodies the belief that an individual can change risky health behaviors by taking personal action. This behavior change is seen as dependent upon an individual’s perceived capacity to cope with stress and to utilize one’s resources to pursue certain courses of action successfully [45]. For example, a highly efficacious older person would be more likely to try to implement better nutrition or an exercise program into their lives than a person with lower self-efficacy. Dzewaltowski, Noble, and Shaw found perceived self-efficacy to be a major force in shaping intentions to exercise and in maintaining those intentions for an extended period of time [49]. Bandura, in his social cognitive theory, put forth that if a person’s self-efficacy can be increased, then that person would be more inclined to pursue healthy behaviors when given the opportunity [46]. This concept suggests that interventions to increase self-efficacy may be particularly important in changing to desirable health behaviors.

Selection of Theories

Of all the theories researched, Social Cognitive Theory represents the best choice for this application. This theory places a great deal of emphasis on self-efficacy, one of its key elements. In fact, the most studied mechanism within the social cognitive framework is self-efficacy [50]. As reviewed previously, self-efficacy represents an important construct for inducing behavior change.

In an attempt to determine which of the following two theories: Social Cognitive Theory or the Theory of Reasoned Action are most effective in predicting behavior, Dzewaltowski found that the Theory of Reasoned Action did not account for any unique variance in exercise behavior not accounted for by the Social Cognitive Theory [50]. In fact, Social Cognitive Theory accounted for more of the variation in behavior than the Theory of Reasoned Action. Social Cognitive Theory was found to be a better predictor of exercise behavior. These findings are consistent with past research and demonstrate that Social Cognitive Theory has been more useful in predicting exercise behavior [41].

Physical Activity, Exercise and Self-Efficacy

Clark and McAuley found that self-efficacy or one’s own belief regarding their ability to carry out certain tasks has been shown to play a key role in the adoption and maintenance of exercise programs [51,52]. This finding is important in health promotion since the attrition rate from exercise programs is approximately 50% within the first 6 months [53]. McAuley found that self-efficacy plays more of a role in the adoption phase of exercise than in the maintenance phase, suggesting that interventions that focus on self-efficacy may be more effective for those older adults beginning to exercise, but less effective for those in the maintenance stage [54]. Different factors may have more importance in the maintenance of the program, such as the person’s health or resources [54].

Self-efficacy, more specifically, is concerned about the judgments an individual makes about whether he/she can do a particular skill but does not actually measure or evaluate the skill level of that individual [40]. Beliefs about efficacy can affect thought patterns that can enhance performance or provide a barrier to performance [44]. McAuley argues that as a person adapts physiologically and psychologically to an exercise regime and it becomes a part of his/ her life, the role of self-efficacy in exercise maintenance is lessened [52]. The person, through experience, demonstrates that he/she can successfully adopt an exercise program and his/her negative cognitions or perceptions about not having the ability or capability of attempting and completing this task will have been restructured through performance. This is parallel with Bandura’s position that our attitudes/beliefs play a large part in what we attempt and what we do not [55].

It has been demonstrated that a person’s beliefs and perceptions regarding the adoption of a particular behavior will greatly enhance or undermine that person’s chances of successfully achieving that behavior change or movement from one stage to another. Furthermore, his/her beliefs or feelings of self-efficacy in successfully completing a task will, in turn, affect his/her level of readiness [55]. For instance, if an older person thinks that he/she is too old to benefit from regular physical activity, then that person will probably not even attempt an exercise program. His/her readiness to begin the adoption phase will be decreased. Through education, this person may learn that older people do in fact benefit from regular physical activity and then his/ her level of readiness will be increased. If he/she knows that he/ she should exercise, but believe that he/she cannot do the exercises properly or safely, then his/her level of readiness will be lower [40].

According to Lachman et al., interventions to increase a person’s sense of control over his/her physical functioning in later life as well as his/her level of self-efficacy in regard to physical activity and/or exercise should be focused on more than simply teaching new skills to enhance physical functioning [55]. These interventions should consider attitudinal and motivational elements as well. In fact, it has been proposed that the most effective way to meet these goals is via a cognitive-behavioral framework focusing on beliefs, motivation, emotions, knowledge, and skills simultaneously [27,57].

Lachman and colleagues suggest that the combination of education and cognitive interventions designed primarily to increase selfefficacy for physical activity can raise an individual’s level of readiness sufficiently for that person to attempt behavior change [56]. Cognitive misconceptions held by older adults appear to interfere with their willingness to attempt an exercise program by lowering their self-efficacy. Can these misconceptions, mostly negative, bring about a change in self-efficacy that would increase the willingness of older adults to undertake an exercise program? The purpose of this study is to explore whether changing negative perceptions will increase the likelihood of older adults engaging in an exercise program. In addition, will it also contribute to the maintenance of that behavior? One of the key techniques used to change negative thinking is cognitive restructuring. Cognitive restructuring is a technique of cognitive therapy that enables one to identify negative, irrational beliefs and replace them with truthful, rational statements [58].

Other concerns facing older adults and education. With these characteristics in mind while developing the psycho-educational intervention, there are several other factors that need to be addressed. Any one of these factors, or a combination of them, could possibly interfere with class attendance of the older learner. The most prevalent of these are their fear of the unknown, transportation, and parking [59-62]. Some older adults fear the competition involved with taking classes and they are afraid that their insufficient training will be exposed [59, 61]. Some elderly individuals report being intimidated by higher learning. A small percentage report trouble with hearing lectures and seeing the visual materials. Some report a desire to learn by listening to presentations with visual aids, but most indicate there are only a few problems associated with older adults attending educational programs [60-62,64].

Research indicates that older adults are as capable of learning as younger people [65]. In fact, their academic performance compares favorably with that of the entire university population [64]. Although older adults do attend university campuses, they have indicated that they prefer to attend educational programs in other settings. These settings are as follows: senior centers, church halls, public schools, town halls and lastly, colleges [60].

The teachers that are most successful in facilitating learning in older adults are knowledgeable about the field of gerontology, flexible and imaginative [59]. These characteristics are very important in keeping the older learner involved in educational programs. Overall, there has been a failure on the part of educators to effectively serve the older learner because less than 5% participate in educational opportunities [61]. The lack of participation by older adults is a problem that gerontologists and health professionals still seek to answer.

The Intervention

A psycho-educational intervention was designed with the older adult in mind since the students were all older adults [66]. Tuition was free, the purchase of textbooks was not required, and the course was not graded. These factors, along with the curriculum design and the cognitive restructuring component, were important in the continuing education of our older population. An overview of cognitive restructuring and its applications are needed at this time.

Cognitive Restructuring

Cognitive restructuring is the process of systematic identification of maladaptive cognitions and attitudes, followed by a focus on the errors in thinking that they exemplify and then by the generation of alternate and more realistic explanations. When applying the technique of cognitive restructuring, participants are taught to systematically replace unrealistic thoughts with more realistic and motivating cognitions through positive self-talk.

One particular area in which cognitive restructuring has proven to be very effective is in the area of psychological aging, and more specifically, memory. Lachman, et al. found that memory strategies and cognitive restructuring were effective in improving older adults’ beliefs about their degree of control in terms of their memory [67]. Caprio-Prevette and Fry found that teaching cognitive restructuring techniques resulted in significantly greater memory performance than teaching traditional memory strategies [68].

Caprio-Prevette and Fry developed a memory enhancement program for older adults aimed at encouraging positive beliefs and behaviors about memory [68]. They also evaluated the effectiveness of cognitive restructuring techniques as an avenue to foster positive beliefs regarding memory. Cognitive restructuring techniques were found to help older adults gain control over their beliefs about their memory [68].

Research has established that certain irrational thoughts or perceptions are related to factors such as low self-esteem, low selfefficacy and locus of control [39,69,70]. Horan found that general cognitive restructuring could have a positive impact on individuals with low self-esteem [71]. Rotter found that both internal and external locus of control is represented by the way in which an individual views their outcome expectancies [39]. Therefore, if a person had an external locus of control and cognitive restructuring was able to modify this locus of control, a likely result would be a change in behavior.

Behavior change is facilitated by an individual’s personal sense of control and whether or not they believe that they can take a particular action. If they do have the belief that they can take a particular action, then they become more interested in doing so. Outcome expectancies are an individual’s perception of the possible consequences of an action. This is directly related to their level of self-efficacy [55]. These outcome expectancies, along with perceived self-efficacy play prominent roles in adopting healthy behaviors, eliminating unhealthy behaviors and maintaining those changes [45]. In this study, the technique of cognitive restructuring will be used to help older adults modify their perceptions or irrational thoughts about physical activity or exercise.

Curriculum Design

The classification of beliefs about the purpose, goals, and objectives of instruction for this psycho-educational course is essential for the development of the curriculum [7]. The purpose of this course was multifaceted. It was designed to incorporate knowledge about physical activity and aging, attitudes about physical activity, and cognitive restructuring techniques to address erroneous beliefs about a person’s ability to exercise.

Goal setting is a function of most national governments and is the building blocks of educational planning [72]. Goals related to the health of the population of the United States have been prepared and are collectively called Healthy People 2010 [73]. Goals relevant to this curriculum design were taken from Healthy People 2010 and an example of this is: Increasing the level of physical activity for older adults [73].

bjectives, or intended learning outcomes, are statements of what the student is to learn which may be facts, ideas, principles, capabilities, skills, techniques, values or feelings” [74]. An objective of this curriculum is to incorporate knowledge regarding physical activity and aging and attitudes about physical activity, and cognitive restructuring techniques to address irrational beliefs about the person’s ability to exercise. Constructivists posit that knowledge is created through the learner’s interaction with a social and physical environment. Learners construct information from prior experiences and modify current thought processes that are inconsistent with their new experiences [75]. Given the principles underlying the curriculum development, as indicated above and the attention to pursue Constructivist forms of instruction, the course was designed to teach cognitive restructuring techniques while engaging in small group format. Small group format allows the maximum amount of individual engagement and learning in a class setting.

Summary

There are many documented benefits of physical activity and exercise, regardless of age. Unfortunately, many older adults do not exercise or participate in any type of regular physical activity. In the above-mentioned intervention, attitudes toward physical activity/exercise and self-efficacy showed positive results. This intervention was sufficient to increase physical activity [66]. Based on the literature, the design of an intervention that utilizes cognitive restructuring techniques is one way to effectively address behavior change.

Conflicts of Interest (COI) Statement

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

References

American College of Sports Medicine (7th Ed.). (2006). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Healthy People 2020 (December, 2010). U. S. Department of Health and Human Services. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers.View

Haskell, W. L., Lee, I. M., Pate, R. R., Powell, K. E., Blair, S. N., Franklin, B. A., Macera, C. A., Heath, G. W., Thompson, P. D. and Bauman, A. (2007). Physical activity and public health: Updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association, Circulation, 116, p. 1081-1093.View

Donnelly, J. E., Jacobsen, D. J., Heelan Snyder, K. S., Seip, R. and Smith, S. (2000). The effects of 18 months of intermittent vs continuous exercise on aerobic capacity, body weight and composition, and metabolic fitness in previously sedentary, moderately obese females. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders, 24, p. 566-572.View

Fitzgerald, S. J., Barlow, C. E., Kampert, J. B., Morrow, J. R., Jackson, A. W. and Blair, S. N. (2004). Muscular fitness and allcause mortality: prospective observations. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 1, p. 7-18.View

Braith, R. W. & Stewart, K. J. (2006). Resistance exercise training. Its role in the prevention of cardiovascular disease. Circulation, 113, p. 2642-2650.View

American College of Sport Medicine: Exercise for Older Adults (1st Ed). (2014). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.View

Hootman, J. M., Macera, C. A., Ainsworth, B. E., Addy, C. L., Martin, M. and Blair, S. N. (2002). Epidemiology of musculoskeletal injuries among sedentary and physically active adults. Medicine Science Sports & Exercise, 34, p. 838-844.View

O’Brien Cousins, S. (1998). Exercise, aging and health: Overcoming barriers to an active old age. Alberta: Taylor & Francis.View

Vuori, I. (2001). Dose-response of physical activity and low back pain, osteoarthritis and osteoporosis. Medicine Science Sports & Exercise, 33(6 Suppl): p. S551-S586.View

Augestad, L. B., Schei, B., Forsmo, S., Langhammer, A. & Flanders, W. D. (2006). Healthy Postmenopausal women – physical activity and forearm bone mineral density: the Nord- Trondelag Health Survey. Journal of Women & Aging, 18(1), 20-240.

U. S. Surgeon General. (1996). Report on physical activity and health.View

Health Canada Active Living Coalition for Older Adults & Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. (1999). Canada’s physical activity guide to healthy active living for older adults. Ottowa, Canada.View

McAuley, E., Elavsky, Sterani, Motl, R. W., Konopack, J. F., Hu, L. and Marquez, D. X. (2005). Physical activity, self-efficacy and self-esteem: Longitudinal relationships in older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 60, p. P268-P275.View

Pekkanen, J. B., Marti, A., Nissinen, J., Tuomilehto, S., Punsar, Karvonen, M. (1987). Reduction of premature mortality by high physical activity: Twenty year follow-up of middle aged Finnish men, Lancet, 1136, p. 1463-1477.View

CDC 24/7: Saving LIves, Protecting People, April, 2020;View

Lee & Park (2008). Does physical activity moderate the association between depressive symptoms and disability in older adults? International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 23(3), 249. 256.View

Dionigi, R. (2007). Resistance training and older adults’ beliefs about psychological benefits: The importance of self-efficacy and social interaction. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 29(6), 723-746.View

Ku, P. W., McKenna, J. & Fox, K. R. (2007). Dimensions of subjective well-being and effects of physical activity in Chinese older adults. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity, 15(4), 382- 397.View

Toseland, R. & Sykes, J. (1977). Senior citizens center participation and other correlates of life satisfaction. The Gerontologist, 17(3), 235-241.View

Ruuskanen, J. M. &Ruoppila, I. (1995). Physical activity and psychological well-being among people aged 65 to 84 years. Age and Aging, 24: 292-296.View

Pate, R. R., Pratt, M., Blair, S. N., Haskell, W. L., Macera, C. A., Bouchard, C., Buchner, D., Ettinger, W., Heath, G. W., King, A. C., Kriska, A., Leon, A. S., Marcus, B. H., Morris, J., Paffenbarger, R. S., Patrick, K., Pollock, M. T., Rippe, J. M., Sallis, J., Wilmore, J. H. (1995). Physical activity and public health: A recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Sports Medicine. Journal of the American Medical Association, 273, 402-407.

World Health Organization Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health: Physical Activity and Older Adults (2011).View

National Center for Health Statistics, National Health Interview Survey, Sample Adult Core component (2018).View

O’Neill, K. & Reid, G. (1991). Perceived barriers to physical activity by older adults. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 82: 392-396.View

Bandura, A. (1977) Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman.

Resnick, B. &Spellbring, A. M. (2000) Understanding what motivates older adults to exercise. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 26, 34-42.View

Rhodes, R. E., Martin, A. D., Taunton, J. E., Rhodes, E. C., Donnelly, M et al. (1999). Factors associated with exercise adherence among older adults: An individual perspective. Sports Med, 28, 397-411.View

McAuley, E., Blissmer, B., Katula, J., Duncan, T. E., & Mihalko, S. L. (2000). Physical activity, self esteem, and self-efficacy relationships in older adults: A randomized controlled trial. Annuals of Behavior Medicine, 22(2), 131-139.View

Lachman, Jette, Tennstedt, Howland, Harris &Peterson.(1997). A cognitive-behavioural model for promoting regular physical activity in older adults, Psychological Health & Medicine; 2(3): 251-61.View

Rosenstock, IM, Strecher, VJ & Becker, MH (1988) Summer, Social learning theory and the Health Behavior Model. Health Education Quarterly, 15(2): 175-83.View

Rosenstock, IM. (1974). The health belief model and preventive health behavior, Health Education Monographs, 2, 328-335.View

Prochaska, JO &Velicer, WF. (1997). The transtheoretical model of health behavior change, American Journal of Health Promotion, 12(1), 38-48.View

Marcus, BH, Rossi, JS, Selby, VC, Niaura, RS & Abrams, (1992). The stages and processes of exercise adoption and maintenance in a worksite sample. Health Psychology, 11(6), 386-95.View

Brug., J., Glanz, K. &Kok. (1997). Applying the transtheoretical model to eating behaviour change challenges and opportunities. Nutrition Research Review, 12(2), 281-317.View

Prochaska, DiClemente & Norcross. (1992). In search of how people change; Applications to addictive behaviors. American Psychologist, 47(9), 1102-1114.View

Ajzen, I. & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes & predicting social behavior. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.View

Fishbein, M. & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention & behavior. An Introduction to Theory and Research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.View

Rotter, J. (1966). General expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcements Psychological Monographs, 80(1), 1-28.View

Bandura, A. (1978). The self-system in reciprocal determinism. American Psychologist, 344-358.View

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. American Review of Psychology, 52, 1-26.View

Bandura, A., Adams, N.E. & Beyer, J. (1997). Cognitive processes mediating behavioral change. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35(3), 125-139.View

Grusec, J.E. (1992). Social learning theory and developmental psychology: The legacies of Robert Sears and Albert Bandura. Developmental Psychology, 28(5), 776-786.View

Bandura, A. (1989). Social Cognitive Theory. In R. Vasta (Ed.), Annals of Child Development, vol 6. Six theories of child development (pp. 1-60). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.View

Schwarzer, R. & Fuchs, R. (1995). Predicting health behavior. Research and practice with social cognition models. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37, 122-147.View

Locke, E A., & Latham, G. P. (1990). A theory of goal setting and task performance, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.View

Schwarzer, R. (1992). Self-efficacy in the adaptation and maintenance of health behaviors: Theoretical approaches and a new model. In R. Schwarzer (Ed.). Self-efficacy: Thought control of action(pp. 217- 242). Washington, DC: Hemisphere.View

Dzewaltowski, D. A., Noble, J. M. & Shaw, J. M. (1990). Physical activity participation: Social cognitive theory versus the theories of reasoned action and planned behavior. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychologist, 12, 388-405.View

Dzewaltowski, D. A. (1989). Toward a model of exercise motivation. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 11(3), 251-269.

Clark, D.O. (1995). Racial and educational differences in physical activity among older adults. The Gerontologist, 35, 472-480.View

McAuley, E. & Jacobsen, L. (1991). Self-efficacy and exercise participation in sedentary adult females. American Journal of Health Promotion, 5(3), 185-207.View

Dishman, R. K., Sallis, J. F. & Orenstein, D. R. (1985). The determinants of physical activity and exercise. Public Health Report, Mar-Apr 100(2), 158-171.View

McAuley, E. (1992). The role efficacy cognition in the prediction of exercise behavior in middle aged adults. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15(1), 65-87.View

Bandura, A. (1989). Perceived self-efficacy in the exercise of personal agency. 4th Annual Conference of the Association for the Association for the Advancement of Applied Sport Psychology, Seattle WA. September 7, 1989.View

Walen, H. R. and Lachman, M. E. (2000). Social support and strain from partner, family and friends: Costs and benefits for men and women in adulthood. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 17(11), 5-30.View

Elliott E, Lachman M. (1989). Enhancing memory by modifying control beliefs, attributions, and performance goals in the elderly. In: Fry PS, editor. Psychological perspectives of helplessness and control in the elderly. North-Holland; Oxford, England: 339–367.

Ellis, A. (1973). Humanistic psychotherapy: the rationalemotive approach.View

Fishtein, O. &Feier, C. D. (1982). Education to older adults: Out of the college and into the community. Educational Gerontology, 8(3), 243-49.View

Price. W. F. & Lyon, L. B. (1982). Educational orientations of the aged: An attitudinal inquiry. Educational Gerontology, 8, 473-484.View

Kingston, A.J. &Dotter , M. W. (1983). A comparison of elderly college students in two geographically different areas. Educational Gerontology, 9,399-403.

Peacock, E. W., & Talley, W. M. (1985), Developing leisure competence: A goal for late adulthood. Educational Gerontology, 11,267-276.View

Theis, S. L. & Merritt, S. L. (1992). Learning style preferences of elderly coronary artery disease patients. Educational Gerontology, 18(7), 677-89.View

Long, H. B. (1983). Academic performance, attitudes, and social relations in international college classes. Educational Gerontology, 9, 471-481.View

March, G. B., Hooper, J. O. & Baum, J. (1977). Lift span education and the holder adult: Living is learning. Educational Gerontology, 2, 163-172.View

Larsen, K. D., Shrestha, S. & Jones, K. ( 2019). The effects of cognitive restructuring techniques on physical activity in older adults. Journal of Public Health Issues and Practices, 3, 141.View

Lachman, M. E., Weaver, S. L., Bandura, M., Elliott, E., Lewkowicz, C. J. (1992). Improving memory and control beliefs through cognitive restructuring and self generated strategies. Journal of Gerontology, 47(5), 293-299.View

Caprio-Prevette, M.D. and Fry, P. S. (1996). Memory enhancement program for community-based older adults: development and evaluation. Experimental Aging Research, 22, 281-303.View

Daly, M. J. & Robert, L.,(1983). Self efficacy& irrational beliefs: An exploratory investigation with implications for counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 30(3), 361-66.

Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of self regulation. Organizational behavior and human decision processes, 50, 248-287.View

Horan, J. J. (1996). Effects of computer- based cognitive restricting on rationally mediate self esteem. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 43(4). 371-375.View

Wiles, J. and Bondi, J. (1998). Curriculum Development: A Guide to Practice (5th.). Upper Saddle River NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc.View

Healthy People 2010; Understanding and improving health. (November, 2000). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett.View

Posner, G. J. &Rudnitsky, A. N (1986). Course Design: A Guide to Curriculum Development for Teachers (3rd Ed.). New York: Longman, Inc.View

Mcneill, J. D. (1999). Curriculum: The Teachers Initiative (2nd Ed.) Los Angeles, Merrill.