Journal of Public Health Issues and Practices Volume 4 (2020), Article ID: JPHIP-165

https://doi.org/10.33790/jphip1100165Review Article

Experiences of social exclusion and inclusion among emerging adult refugees from African Great Lakes Region

Victory Osezua, MPH1*, Doroty Sato2, MBA, MSc, Lesley M. Harris2, PhD, MSW

1School of Public Health and Information Sciences, University of Louisville, KY, 40292, USA.

2School of Kent Social Work, University of Louisville, KY, 40292, USA.

Corresponding Author Details: Victory Osezua, Master of Public Health, University of Louisville, KY, 40292, USA. E-mail: victoryosezua@gmail.com

Received date: 10th April, 2020

Accepted date: 18th May, 2020

Published date: 22nd May, 2020

Citation: Osezua, V., Sato, D., & Harris, L.M (2020). Experiences of social exclusion and inclusion among emerging adult refugees from African Great Lakes Region. J Pub Health Issue Pract 4(1):165.

Copyright: ©2020, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Abstract

This study explores and describes social exclusion and inclusion among emerging adult refugees from the African Great Lakes region fleeing the war in the Democratic Republic of Congo. A constructivist grounded theory approach was employed to conduct twelve in-depth interviews with emerging adult refugees aged 18–25 years old. Findings suggest that emerging adult refugees experience discrimination, dehumanization, and loss of identity during pre- and post-migration in the US. In response, social inclusion is promoted through resilience and establishing a community. The findings suggest that young refugees value mentorship to establish social inclusion through community building. This study also suggested that programs and future research build on the existing strengths of young refugees and communities to achieve sustainable refugee programs and initiatives.

Keywords: Social Inclusion, Social Exclusion, Refugee, Qualitative Research, Africa, youth, Grounded Theory

Introduction

In 2003, fifteen African countries were involved in conflicts and civil wars leading to eight million people seeking refuge or asylum in other countries [1]. The Great Lakes Region in Africa which includes the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Rwanda, Uganda, Burundi, Kenya, and Tanzania has been affected by civil strikes for decades [2]. According to the International Rescue Committee [1], approximately 2.3 million people from the African Great Lakes Region were displaced internally, and 70,000 crossed the borders to neighboring countries. Although the African Great Lakes Region refugees reside in different countries in sub-Saharan Africa, Rwanda, Uganda, Burundi, and Tanzania are the leading host countries providing asylum [3]. For most displaced individuals, resettlement followed a period of transition spent in either an urban or rural refugee camp. These camps varied in educational and job opportunities for refugees. Depending on the country in which the camp was situated, policies contributed to the refugees’ experiences of inclusion or exclusion within the camp. For some refugees unable or not desiring to return to their home country, the United States is a resettlement country of choice. Since 2000, the United States resettled nearly 410,000 from African Countries, 11,000 coming from the Great Lakes Region [4]. Of the refugees resettling in the US, 55% were young adults aged 15-44 years and 40% were children under 15 years old [4].

Not surprisingly, successful resettlement into the United States is difficult. Obstacles presented in the refugee camps make transition to the United States challenging both in finding a sense of inclusion within the refugee camp, and in developing skills that could be transferable to the resettlement country. This lack of inclusion, while difficult for all refugees, is particularly difficult for emerging adults, defined as individuals in late adolescence to young adulthood, generally between the ages of 18-25 [5]. Many emerging adult refugees have experienced war and conflicts in their home countries, therefore psychological and cognitive development are often interrupted, increasing the risk of adverse health outcomes [6-8].

This research study focuses on the experiences of 12 emerging adults from the Great Lakes Region of Africa who spent time in a refugee camp before resettling in the United States. This qualitative study examines the factors that contributed to social inclusion and social exclusion both within the refugee camp and within the resettlement country.

Social exclusion and inclusion among refugees

Social exclusion results when a complex set of variables, often present within an organized system, prevents an individual or group from accessing the resources necessary to maintain social, economic, cultural and political wellbeing [9]. Social exclusion occurs when inadequacies within the society fail to ensure that all individuals and communities fully participate within their society [10-12]. Studies have shown that immigrants experience culture shock and a feeling of powerlessness due to a limited understanding of their new environment [13]. This is true whether the environment is restricted, as in refugee camps, or chosen, as in a resettlement country. Discrimination is a substantial form of social exclusion for immigrants [14-16]. For emerging adult refugees, discrimination can be more harmful because these years are essential in the exploration of identity and establishing a place within society [16,17].

In contrast, social inclusion is the degree to which people feel integrated into a variety of relationships, participate in dynamic organizations, sub-systems, and are connected to structures that establish everyday life [18]. Social inclusion includes social justice and human rights but also enlarges the full potential of each human being [19]. For emerging adults, social inclusion requires opportunities to participate in society and belong to their cultural community [20]. For African refugees, the experience of social inclusion depends on a range of factors offered by the host country,such as the climate, cultural and linguistic competency resources, educational opportunities, proximity to members of one’s own ethnic group, and job locations [21].

In this grounded theory study, three theories are used as theoretical sensitizing concepts: symbolic interactionism, pragmatism, and bourdieu’s theory of social capital and cultural reproduction. Applying these theories to the study provides a lens by which to understand how emerging adult refugees approach the concept of social exclusion and inclusion. In symbolic interactionism, the interpretive process becomes clear when participants’ meanings/and or actions become enlightening or their situations change [22]. For the 12 study participants, migrating to the US presented a situational change whereby social exclusion or inclusion resulted. Applying the symbolic interactionism provided the opportunity to explore participants’ meanings of social exclusion.

Also, pragmatism was used to explore the practical difference resettlement makes and ascertain what resources emerging adult refugees find useful. Pragmatism allowed for a better understanding of the emerging adults’ experience with social exclusion and which strategies were most effective in promoting social inclusion in their everyday lives [23]. In addition, we applied Bourdieu’s theory to understand how participants apply their experiences, beliefs, and values to promote social inclusion. This theory explores dimensions of capital (economic, cultural, and social capital) in relation to one’s class, including how the social capital that emerging adult refugees acquire through experiences became a resource in dealing with social exclusion and promoting social inclusion [24].

Since each emerging adult refugee interprets their personal experiences in a way that makes sense to the individual, each young person has a unique perspective about what it means to be socially excluded or included. This is true of their experiences living in a refugee camp as well as their experiences once transitioned to a resettlement country. Therefore, the focus of this research is limited to emerging adult refugees from the Great Lakes Region of Africa, who have spent a minimum of one year in a refugee camp, and resettled in the United States for a minimum of 12 months. This study aims to explore and describe the experience of social exclusion and inclusion among emerging adult refugees. Two research questions were developed:

What are the meanings ascribed to the experiences of social exclusion and inclusion?

What are the strategies engaged in overcoming social exclusion and promoting inclusion?

Methods

Study Design

We conducted a qualitative study informed by Constructivist Grounded Theory [22] to develop a context-specific framework whereby accessing the meanings and strategies that emerging adult refugees associated with social exclusion and inclusion. The Constructivist Grounded Theory approach enabled the research team to explain the processes, actions, or the internal and external interactions shaped by the participants’ views. [22].

Recruitment

For this research study, participants within 18-25 years old were considered emerging adults. Recommendations from community partners such as resettlement agencies and community organizations serving refugees from the Great Lakes region resulted in a participant pool of emerging adults who were fluent in the English language, resettled in the United States at least one year, but no longer than ten years. The length of residence was determined based on refugee status, which runs for five years with recipients eligible to apply for citizenship after this period. Two potential participants were unable to participate due to to time constraints and the age group in the inclusion criteria.

Sampling

Purposive sampling strategies were used to identify and select participants resulting in 12 interviews with emerging adult refugees from the African Great Lakes Region. Refugee resettlement offices, community health centers, and clinics posted flyers describing the study. During the recruitment process, purposive sampling was assisted by community partners who assisted with study recruitment by providing a list of potential participants to increase the sample size. Participants were also recruited through snowballing sampling. Lastly, theoretical sampling added another layer of sampling to develop the core categories of social exclusion and social inclusion.

Data Collection

This research was conducted in a mid-sized US city. Data was collected via open-ended interviews using a semi-structured interview guide. Informed consent was obtained before data collection. The survey and in-person interviews were conducted by a researcher at partner community centers, refugee resettlement services office, and in a private location of the participants’ choosing, including their own home. All interviews were audio-recorded and lasted between 90 to 120 minutes. Participants were not compensated for their involvement in the study. Immediately after each interview, observational field notes were written.

Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted using Constructivist Grounded Theory analytic techniques [22] and Dedoose software was utilized as an organizational tool. All interviews were transcribed verbatim and checked for accuracy. Four phases of coding-initial, focused, axial and theoretical were employed to develop a context-specific framework [22,25]. Authors began initial coding by examining the interview transcripts line by line for gerunds or actions that described how participants interpreted and handled situations [26]. A series of focused codes were drawn from open codes that appeared frequently and suggested significance. Authors then conducted axial coding by identifying relationships between categories derived from the initial coding. By using peer debriefing and consensus-building around themes [27], the research team built a codebook consisting of 37 code families with definitions. After the codebook was established, research team members coded half of the transcripts and conducted intercoder reliability (κ = 0.98) to ensure code agreement.

On Deedose, the focused codes were collapsed into families with descriptions. Then, theoretical coding was done by coding the data set to saturate the theory of social exclusion and inclusion. Besides coding, other analytical tools were used to conceptualize the data. Memo writing was used to examine the research experience, positions, and interpretations. Observational field notes included events seen or heard during the interview, interpretations of the interview, early hunches, self-reflection, and self- critique of the interview [28]. Also, situational analyses were conducted to describe the situational factors related to emerging adult refugees’ experience using a messy and ordered map [29]. In order to achieve theoretical saturation, three participants were selected and re-interviewed. We then explored areas where our data were thin and had not reached saturation. New participants were sampled theoretically to fully understand the social process.

Rigor

The criteria for rigor were employed to ensure a rigorous study [30]. Credibility was enhanced through member checking and peer debriefing. Data was collected and coded separately by research team members who met regularly to discuss and identify themes and meanings. Member checking was also conducted to authenticate study findings with participants [30]. To improve transferability, multiple methods were used for data collection: interview, observational field notes, and follow-up interviews. Also, the research team met to review negative cases and re-interviewed individuals as necessary when data collection methods required clarification in order to deeply understand participants’ answers to interview questions.

All study procedures were approved by the University of [blinded for review]. Research team members engaged in reflexivity to incorporate a continuous examination of bias through the research process. Also, research team members (V.O and D.S), who are both immigrants, approached this study as outsiders to the African Great Lakes region. Researchers engaged in reflexivity by writing comprehensive observational field notes and memos during and after interviews to address possible bias.

Results

Participant Characteristics

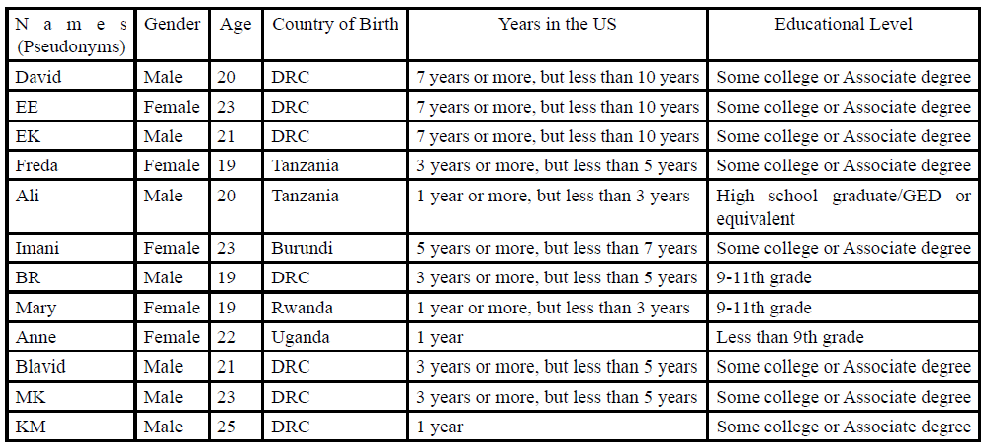

A total of twelve emerging adult refugees were interviewed. Table 1 details the demographic of the sample. There were 58.3% female and 41.7% male participants ranging in age from 19 – 25 years (mean = 21.25, S.D = 1.96). They had lived in the US from one to five years (Mean = 3.1, S.D = 1.44). 50 percent of the participants were born in DRC, 25% in Tanzania, while the rest were born in Burundi, Rwanda, and Uganda. With respect to educational level, most respondents had some college or associate degree (66.67%) or were high school students (16.67%).

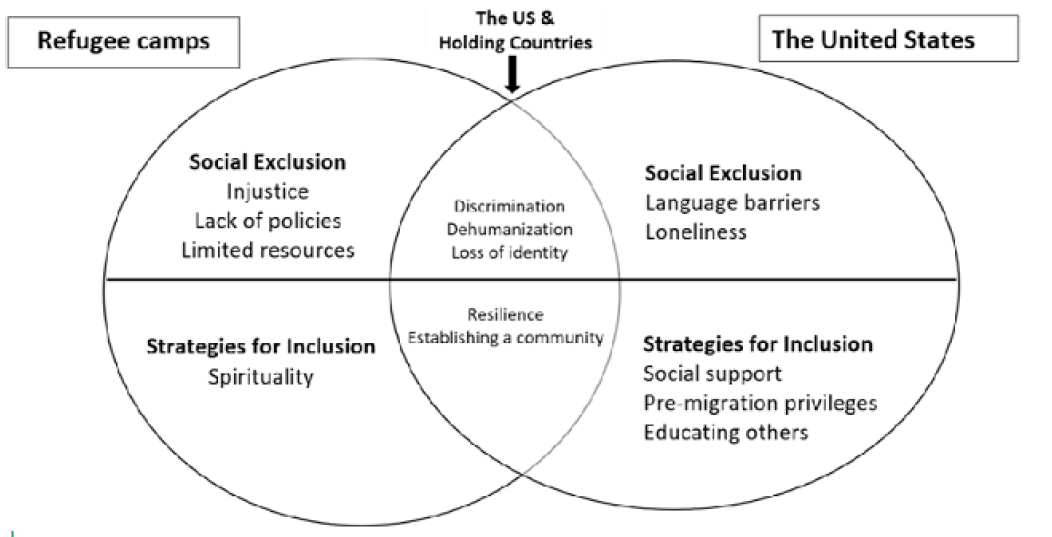

The findings of this study are explained below using the context specific framework (Figure 1). The analysis of participants’ stories reveals the experience of social exclusion, and how social inclusion was promoted. The framework is explained in three main categories: participants’ experiences before migration in refugee camps or holding countries, after migration to the US, and shared experiences common among most participants during pre-and post-resettlement. For the purpose of this research, the holding country is defined as the temporary location of participants while awaiting resettlement in the US.

Participants described their experiences of social exclusion in holding countries as injustice, limited policies, and few resources to support assimilation. Among varying coping mechanisms, spirituality was noted as a primary strategy to promote social inclusion within the holding countries. Once resettled in the US, social exclusion took several forms, including a limited ability in interpretation and use of the English language, loneliness, and culture shock. Participants developed and utilized strategies to promote social inclusion in the US such as pre-migration privileges, social support, and educating others. Although each participant shared distinct experiences of exclusion and inclusion, all participants voiced commonalities regarding exclusion in both the holding country and the resettlement country. These shared experiences were discrimination, dehumanization, and loss of identity. Two strategies employed by all participants who found success with inclusion, whether pre- and post-settlement were resilience and the ability to establish a community with friends, family relatives, and teachers.

Social Exclusion in Holding Countries

Based on participant feedback, emerging adults described common experiences in holding countries regarding social exclusion. Three forms of social exclusion emerged, regardless of whether the camp was rural or urban: injustice, lack of equitable policies, and limited resources.

Injustice: Most participants described what they experienced as unfair enforcement of government power and control as instances within the camp leading to social exclusion. Participants in this study expressed prejudice from the government, police force, and workers in the refugee camp who were locals. All emerging adults who lived in refugee camps, regardless of the time spent there, stated that opportunities were limited because of their refugee status. For example, if treated unfairly by an unjust police officer or locals, they were unable to report to the government authorities or stand up for their rights. Blavid, a 21-year old male Burundian who lived in a Tanzanian refugee camp shared an example of injustice in refugee camps:

We just followed the order until we get out of the refugee camp. If you go outside of the camp area, you’ll get in trouble and go to jail. They set you up on different stuffs; they can accuse you of stealing or being in a gang. You may end up with 25 to 30 years in jail or maybe killed the moment they're taking you (Blavid, 21).

Lack of equitable policies: The policies that applied to refugees in the camps were different from the policies that applied to citizens outside of the camp. Most participants expressed that the absence of equitable policies for refugees in the camp led to social exclusion. Some participants were unable to work, obtain education beyond primary school, or afford basic social needs due to their refugee status. Anne, a 22-year old female, who grew up in a Ugandan refugee camp said social exclusion occurred when her family was unable to continue her education due to cost and their inability to work as refugees. She explained, “I could not go to complete my secondary school education. We were chased out of school because my parents could not afford to pay the school fees. You can be home for weeks when you don’t have school fees.”

The lack of fair policies favoring quality education for refugees made it difficult for refugees to afford to continue their education. Therefore, exclusion within education created wide educational gaps among emerging adult refugees upon arrival to the US.

Limited resources: Compared to the citizens of holding countries, refugees experienced severe inadequacies in terms of resources. These resources included jobs, health care services, support from teachers, financial resources, and food supplies. Young refugees were often unable to find jobs because of their non-citizenship status. MK, a 23-year old refugee explained how the limitations of refugee status made him feel excluded. “There are not so many jobs in the refugee camp, and we are not allowed to work outside the camp”. Especially in rural camps, refugees were unable to find jobs and provide for their families as most jobs were for citizens. The inability to work contributed to social exclusion and feelings of being an outsider. Further, obtaining resources is linked to financial stability, continuing one’s education, and securing basic necessities added to social exclusion.

Strategies for inclusion in holding countries

Spirituality: While experiencing social exclusion as a refugee, many participants developed strategies to promote inclusion within their community. Also, they expressed the role faith played in overcoming challenges associated with living in refugee camps. EK is a 21-year old Congolese. Growing up in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Christianity helped him find strength through the challenges of fleeing the war with his family. He explained, “I am a religious person. This is what makes me stronger. My faith means a lot to me. In Africa, my dad was a pastor, so we learned to thank God in everything” (EK, 21). Many participants gathered for prayers as individuals, families, and communities during hard times. EK’s faith played an important role in handling the challenges of the war and the feeling of exclusion in a holding country. Emerging adult refugees also explained that other strategies stemmed from survival; these included: bargaining with camp workers, working for a local, having a benefactor who is a citizen, and learning the local language.

Social Exclusion in the United States

Social Exclusion continued once emerging adult refugees entered the United States. Although factors differed from exclusion experiences within refugee camps, social exclusion continued, taking the forms of loneliness, language barriers, and culture shock.

Loneliness:Participants expressed how the experience of being a new refugee was isolating. The educational system, one of the primary forms of exclusion in refugee camps, continued to create social exclusion for emerging adult refugees in the US. Participants reported that being a new refugee student could be lonely as the educational system was different from what they were used to. EK described his experience about being disoriented and lonely in his high school. He said, “I felt like I didn’t belong there. Like, I go to the classroom, sit down, and do not understand anything” (EK, 21). Ali, a 20-year old male described his experience with loneliness as a new refugee student in a US school:

When I started going to school, I felt very lonely because I did not know anybody, and I could not speak to anybody. Everything was new to me when I looked around. Sometimes, I go into the cafeteria and do not get any food because there was nobody to show me around to say you have to go here, you have to do this (Ali, 20).

Ali also explained: “it is like you’re born twice.” The process of learning new social skills felt like one was starting over as a newborn.

Language barriers: Although emerging adult refugees were required to be fluent in the English language to participate in the study, they entered the US with varying language skills, including no English at all.

Limited English proficiency made participants feel “silenced.” A participant explained, “The first time I started to speak English was difficult. Taking the bus home and going places was so difficult because if I tell somebody something, they would not understand me because I do have an accent” (KM, 25). Also, participants described feeling silenced due to language difficulties. Although there were school programs and services, utilizing them appeared difficult due to language barriers and cultural competency. Some participants were unable to receive help because of the difficulty in expressing themselves. A participant explained, “If you don’t speak English, there is no way for you to speak up about something or to ask for something. You’ll just be quiet. In that case, you won’t get any support because they don’t know what problem you have” (Ali, 20).

Culture shock: Although language barriers and isolation created conflicts, participants explained that in their cultures, certain actions that are deemed respectful are interpreted differently in the US. David (20) explained, “In my culture if an older person walks into the room, the younger person has to offer a seat if there are no chairs to sit. This is something you won’t see here.” (David, 20). The difference in behaviors in the US was unfamiliar to young refugee adults and reinforced the feeling of social exclusion and culture shock. Experiences with culture shock led to feelings of not belonging which was reported as a form of social exclusion.

Strategies for inclusion in the United States

All participants developed strategies to promote social inclusion within the US, which made the resettlement process easier. These strategies included pre-migration privileges, social support, ignoring discrimination, educating others, and motivation to succeed.

Pre-migration privileges: Most participants believed pre-migration privileges were strategies to promote inclusion. These included earning a high school diploma and learning the English language or a vocational skill prior to resettlement. For example, Blavid’s father taught school in a Tanzanian refugee camp. He explained, “My daddy taught me English in camp. I used to pretend like I was going to help him out in school, but he taught me English. When I came here, I completed one year of ESL and transferred to a normal high school (Blavid, 21). He was able to enroll in college sooner than his less English proficient classmates. For Blavid and other emerging adult refugees, arriving in the US with some privileges made the post-migration easier. Other skills mentioned were having money, automobile repair skills, reading and writing proficiency in Swahili, Kibeembe, or Kinyarwanda.

Social support: All participants in this study agreed that a strong social support network promoted social inclusion. Support received from teachers, church communities, organizations and friends helped young refugees learn about American culture. Participants voiced high regard for resettlement agencies for offering social support. Mary, a 19-year old high school student explained. “As a refugee here, I did not have a hard time because of [the refugee resettlement organization]. They were always there for me and always offered to help. When you need help, they are always there for you” (Mary, 19). In addition, most participants found strength through the social support they received from friends and family whether it be encouragement, motivation or problem sharing. BR, a 19-year old male agreed that his support system made him stronger. He said, “Being around people I am familiar with makes me strong. Anytime I have a problem, I am strong because I have friends and family. To have these people in my life makes me strong”. (BR, 19).

Educating others: The lack of knowledge about refugees’ past experiences added to discrimination and bias. Many young refugees educated their friends, teachers and classmates about their refugee status. Ali, a 20-year-old male explained an experience in high school that made him realize the importance of educating his peers.

I remember I did a project on the refugee crisis. I asked students, what came to mind when they hear the word refugee. Most of them were like hmmm this was their first time or did not know what it meant. So, I was like hmm! we are living in a place with people who don’t know us. We just feel like we are alone (Ali, 20).

For Ali and other emerging adults, educating their classmates and communities about what it means to be a refugee created a safe space for their existence, reduced stigma, limited experiences of discrimination and became a successful strategy for inclusion.

Shared experiences of social exclusion and strategies for social inclusion in the US and holding countries

Although participants told different stories, researchers noted that commonly shared themes emerged. Specific phrases and word choices were repeated throughout the interviews alerting researchers of the significance of these shared experiences. These were discrimination,dehumanization, and loss of identity for social exclusion and experiences are resilience and establishing a community for social inclusion.

Shared experiences of social exclusion in the US and holding countries

Discrimination: Participants explained that while living in a refugee camp, they shared the experience of discrimination and were not welcome in holding countries. Imani, a 23-year-old Burundian female who lived in South Africa before resettling in the US explained the feeling of being socially excluded. “South Africa was the worst! They didn’t like refugees. They tell you to your face, we don’t want you guys!” (Imani, 23). For KM, a 25-year old Congolese male, he explained that “in the US equal doesn’t mean entirely equal”. He described an experience where he lost his job due to racism and nepotism. Even though he put his best forth at work, he was replaced by his supervisor’s son who knew nothing about the job. He explained: “I felt it was discrimination. This guy knew nothing on the job, but he was White and the manager’s son. Statement about equal employment was on the company’s wall but not actually practiced” (KM, 25).

Also, emerging adult refugees believed that dwelling on discrimination caused it to persist. Some participants explained discrimination was in the form of social stigmas such as mockery and racism. Freda, a 19-year old female believed that ignoring bullies and discrimination made it cease. She explained: “I have a friend who doesn’t like people talking behind her. I tell her not to worry about this thing. When you ignore them, they’ll leave you. Just be quiet and they will quit what they are doing” (Freda, 19). Young refugees ignored discrimination to maintain psychological well-being and protect themselves from pain. EK, a 21-year-old Congolese male described how ignoring discrimination helped: “If I go to a place that I do not feel welcome, I just ignore" (EK, 21). For some participants, ignoring discrimination was a strategy to manage social exclusion.

Participants described how some immigrants looked down on newly arrived refugees due to their inability to speak the English language fluently. Many participants arrived in the US expecting to be received by other African immigrants but to their surprise, some immigrants were not friendly to them. “Even among us immigrants, some put other people down. We are all immigrants but when they learn the language, they feel like they are better” (Freda, 19). Discriminatory experiences as such led to participants feeling excluded and not part of society.

Dehumanization: Emerging adult refugees described the experience of dehumanization as being regarded as an animal. The shared experience of dehumanization in the US was likened to racism and bullying. Some participants described these experiences in school and social media. EE, who is currently a college student, described a dehumanizing experience in high school and social media. She recalled, “a girl from school took a picture of my sister’s hair and put it on Facebook and captioned it “African Monkey.” We were so mad about the picture and that they called us monkeys” (EE, 23).

Participants felt dehumanizing experiences led to social exclusion. The inability to afford healthy meals, take care of one’s family or be likened to animals provoked feelings of social exclusion whether during pre- or post- resettlement.

Loss of Identity: Losing one's identity was a pertinent category in the shared experience of young refugees from the African Great Lakes Region. Many emerging adult refugees were either born in refugee camps or fled their home countries at a young age, and some participants had few memories of the culture of their countries of origin. In such situations, they neither identified with their naturalized country nor were they recognized citizens of their country of birth. Ali (20) explained: “My parents are Congolese, so I’m a Congolese citizen. I wasn’t born there and never been there. It is confusing to be a citizen of a country where I’ve never been. I was born in Tanzania, but I’m not a Tanzanian”. In many African countries, citizenship is attained by one’s parent country, this could be beneficial when a person is born and raised in the same country as their parents. Being born and raised in another country where one is not accepted as a citizen can result in feelings of being an outsider or losing one’s ethnic identity.

Among the repeated experiences participants shared was that being resettled in the US was also accompanied by the loss of identity. In order to understand the American culture, African emerging adult refugees tried to fit in. According to participants, it was difficult as American values were substantially different from African values. M.K. described an exhaustive experience of explaining where he is from, which for him was a signal of not being accepted. “I feel like I do not belong here, and I am out of the place. Every time I meet a new person, the first question is where I am from just because of my accent. I'm tired of it (MK, 23)”.

Shared strategies for social inclusion in the US and holding countries

Participants’ described two shared strategies, resilience and establishing a community, to promote social inclusion regardless of whether the camp was rural or urban, whether in the Great Lakes Region of Africa or the US.

Resilience: Finding strength through past negative events and determining to succeed while facing difficult times, enabled participants to build resilience. Imani, a 23-year old Burundian single mother who resettled in the US from South Africa found strength through her past experiences.

My experience with wars, the way my aunt treated me and moving to the US without my parents make me very strong. I am strong because I have been through a lot. Nothing can hurt me. When you’ve been through a lot, your heart gets tired of being hurt and whatever happens, feels normal. (Imani, 23).

Imani and other participants repeatedly shared stories where they found strength through past negative experiences, thereby developing resilience to overcome social exclusion experiences in the US.

Emerging adults achieved resilience by having the motivation to succeed. Having a sense of purpose and exhibiting self-motivation mitigated the experience of social exclusion. For instance, Freda, a 19- year old Congolese refugee shared that she was motivated to succeed by helping people in need. She stated, “Success is not about doing something big but accomplishing something you're passionate about. It's important that I do something that really pushes me to succeed not just as a businesswoman, but what I am really passionate about” (Freda, 19). Although participants experienced social exclusion and difficulties during the resettlement process, they showed resilience through a zeal to succeed and achieve their dreams.

Establishing a community: The second shared strategy for inclusion was establishing a community. Participants revealed the importance of a community in the US to feel connected to their new community. For some, making friends in schools was an outlet for participants to forget past experiences with the war by joining a school sports team, or school club brought about feelings of belonging to the new home. “Going to school was a way to forget the wars. There was peace and I could go to school. I was always smiling, made friends, and felt smart again because I liked Math” (MK, 23). Study participants established new communities in schools, churches, or community centers.

Discussion

This is the first study that addresses the experiences of social exclusion and social inclusion among emerging adult refugees from the African Great Lakes Region, a geographic area that contains 6 African countries. These regions share similar identities and ethnic dimensions and experiences of political violence in the past [31]. The study participants described limited ability in interpretation and use of the English language, loneliness, and culture shock as experiences of social exclusion. Our findings are in agreement with a study on cultural shock and adaptation in immigrant populations [13]. Social exclusion occurred as a result of difficulties in managing the new environment in the US. Many participants in our study employed intrinsic strategies to promote social exclusion while in the refugee camps. These strategies included bargaining with camp workers, having a benefactor who is a citizen, leaving the camp to work in the city or working for a local citizen. However, some of these strategies were considered illegal practices in the refugee camps but were employed as survival strategies to promote social inclusion.

Emerging adult refugees explained that social inclusion can be linked to empowering people to achieve their full potential by engaging fully in their respective communities. Our participants valued mentorship to establish social inclusion through community building. For these emerging adults, social support played a major role in cultural adjustment in the US. The literature suggests that social support aids the adjustment of refugees and immigrants resettling in the US [14,19,31].

While some participants had articulated their experience with discrimination in American schools after migrating to the US, many others continued to be attracted to the opportunity to attend and receive an excellent education in these US schools, thus resulting in an interesting antithesis in the lives of most of these participants. Going to school was an outlet for participants to forget past experiences with the war by joining a school sports team or school club generated feelings of belonging to their new community. Even though literature revealed that discrimination is a significant form of social exclusion [14-16], this study revealed that some immigrants who have resettled in the US for a longer time than our study participants looked down on newly arriving refugees who were getting settled in their new environment. This experience caused young refugees to have unexpected feelings of exclusion from fellow African immigrants.

Although a breath of research exists about emerging adult refugees on the immigration and acculturation experience, this is the first study that focuses on a particular geographic region of Africa, the Great Lakes Region. The findings from this study add to the existing body literature on refugee and immigrant studies.

Limitations

The strength of this study lies in gaining a culturally specific understanding of social exclusion and inclusion of emerging adult refugees from the African Great Lakes Region of Africa. However, some limitations were observed. The participant pool was limited to emerging adult refugees who were fluent in the English language. This criterion excluded a significant portion of this population who had valuable information to share but were not fluent. Another limitation was the current US political climate regarding immigration in the era of the Trump administration that created distress in the refugee community. As a result, many potential participants were scared to be interviewed which negatively impacting recruitment. Of the original pool of 50 potential participants, 12 met the study criteria.

Conclusion

A great deal of research is available about the refugee population. Certain geographic areas, North Africa, the Middle East and parts of Southeast Asia, etc. have captivated attention from researchers, educators and philanthropists alike. However, the African Great Lakes Region, a complex political, economic and geographic region has not, until this project, been singled out for study on social exclusion and inclusion. Researchers interest in emerging adults (aged 18-25) promoted a qualitative study exploring questions of exclusion and inclusion in both the holding countries (refugee camps) and the US settlement country.

The analysis of social exclusion experienced by emerging adult refugees from the African Great Lakes Region suggested distinct forms of social exclusion pre-and post-migration to the US,including injustice, inequitable policies, limited ability in interpretation and use of the English language, loneliness, and culture shock. Study participants also employed different strategies to establish a sense of belonging during each phase of their migration process. A foundation of spirituality was rated highly as a positive strategy for several participants. In addition to the individual coping strategies and exclusionary behavior, participants identified similar/ shared behaviors that helped them gradually shift from being excluded to experiencing inclusive activities and attitudes. Resilience and building social supports were strategies mentioned by the majority of participants as essential to feelings of inclusion and belonging. For many participants, accessing positive educational opportunities made the difference between social exclusion and social inclusion. Of primary concern was the need for language accommodation for refugees who were not fluent in the English language.

As educational institutions provide both barriers and opportunities, future research could examine the development of additional strategies for social inclusion during post-resettlement. Given the reality that the majority of emerging adults spend some time in high school once moving to the US, further studies could consider the specific forms of discrimination present in the school system, and how instructors and administrators could examine bullying from the perspective of refugee students. We believe it is also essential for researchers to examine how young refugees situate themselves within a new community in an attempt to acquire social resources and gain a sense of belonging. Finally, it would be valuable for future research to examine the influence of inclusive communities, refugee resettlement organizations, centers for equity, and diversity programs on the well-being of emerging adult refugees.

Although emerging adult refugees experienced various challenges pre-and post-resettlement; they developed strategies to face and often overcome these barriers of resettlement. Building on the intrinsic strengths of young adult refugees who have been successful in navigating the resettlement process can be helpful to newly arriving refugees. Furthermore, participants recommended that educational and community-based programs employ cultural competency when creating the program design and implementation. Participants expressed the need for youth mentors to assist them upon arrival to the country. Mentorship programs with young people who are knowledgeable of the culturally specific experience of an African refugee can help alleviate the feeling of social exclusion. Therefore, this study suggests that programs and future research build on the existing strengths of young refugees and communities to achieve sustainable refugee programs and initiatives. Acknowledging that social exclusion and inclusion are strong determinants for success in the US, research focused on exploring and describing the experience of social exclusion and inclusion among emerging adult refugees will advance the body of research about this resilient population and engage their participation in developing policies, programs, and incentives to promote social inclusion for emerging adult refugees.

Conflict of interest:

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

References

IRC- International Rescue Committee (2014). Experiences of refugee’s women and girls from The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC): Learning from IRC’s women protection and empowerment programs in DRC, Tanzania, Burundi, and Uganda. View

Bussy, J. M., & Gallo, C. J. (2016). The Great Lakes Region of Africa: Local Perspectives on Liberal Peacebuilding from the Democratic Republic of Congo. In The Palgrave Handbook of Disciplinary and Regional Approaches to Peace (pp. 312-324). Palgrave Macmillan, London.View

USA for United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), 2019. Who is refugee.View

Office of Refugee Resettlement. (2016). FY 2015 served populations by state and country of origin (refugees only).

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469-480.View

Bischoff, A., Denhaerynck, K., Schneider, M., & Battegay, E. (2011). The cost of war and the cost of health care-an epidemiological study of asylum seekers. Swiss medical weekly, 141, w13252.View

Dubois, J. L., Huyghebaert, P., & Brouillet, A. S. (2007). Fragile States... An analysis from the capability approach perspective. In Ideas Changing History Conference.

Kirmayer, L. J., et al. (2011). "Common mental health problems in immigrants and refugees: general approach in primary care." Cmaj 183(12): E959-E967.View

Pierson, J. (2002). Tackling social exclusion (Vol. 3). Psychology Press.View

Power, A., & Wilson, W. J. (2000). Social exclusion and the future of cities. LSE STICERD Research Paper No. CASE035.View

Abrams, D., Hogg, M. A., & Marques, J. M. (Eds.). (2004). Social psychology of inclusion and exclusion. Psychology Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469

Mkanta, W. N., Eustace, R. W., Reece, M. C., Alamri, A. D., Davis, T., Ezekekwu, E. U., & Potluri, A. (2018). From images to voices: A photo analysis of medical and social support needs of people living with HIV/AIDS in Tanzania. Journal of Global Health Reports, 2. View

Winkelman, M. (1994). Cultural shock and adaptation. Journal of Counseling & Development, 73(2), 121-126.View

Herz, M., & Johansson, T. (2012). ‘Doing’ social work: Critical considerations on theory and practice in social work. Advances in social work, 13(3), 527-540.View

Fangen, K. (2010). Social exclusion and inclusion of young immigrants: Presentation of an analytical framework. Young, 18(2), 133-156.View

Wray-Lake, L., Syvertsen, A. K., & Flanagan, C. A. (2008). Contested citizenship and social exclusion: Adolescent Arab American immigrants' views of the social contract. Applied Development Science, 12(2), 84-92.View

Flanagan, C. (2003). Trust, identity, and civic hope. Applied Developmental Science, 7(3), 165-171.View

Balenzano, C., Moro, G., & Cassibba, R. (2019). Education and Social Inclusion: An Evaluation of a Dropout Prevention Intervention. Research on Social Work Practice, 29(1), 69-81.View

Gidley, J. M., Hampson, G. P., Wheeler, L., & Bereded-Samuel, E. (2010). From access to success: An integrated approach to quality higher education informed by social inclusion theory and practice. Higher Education Policy, 23(1), 123-147.View

Correa-Velez, I., Gifford, S. M., & Barnett, A. G. (2010). Longing to belong: Social inclusion and wellbeing among youth with refugee backgrounds in the first three years in Melbourne, Australia. Social Science & Medicine, 71(8), 1399-1408.View

Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.View

Charmaz, K. (2017). The Power of Constructivist Grounded Theory for Critical Inquiry. Qualitative Inquiry, 23(1), 34–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800416657105View

Bourdieu, P. (1973). Cultural reproduction and social reproduction. London: Tavistock, 178.View

Corbin, J. M., & Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative sociology, 13(1), 3-21.View

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2015). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory 4th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Erlandson, D.A. (Ed.). (1993). Doing naturalistic inquiry: A guide to methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage.View

Schatzman, L., & Strauss, A. L. (1973). Field research: Strategies for a natural sociology. Prentice Hall.View

Clarke, A. E., Friese, C., & Washburn, R. S. (2017). Situational analysis: grounded theory after the interpretive turn. Sage Publications.View

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry (vol. 75). In: Sage Thousand Oaks, CA.View

Kanyangara, P. (2016). Conflict in the Great Lakes Region: root causes, dynamics and effects. conflict trends, 2016(1), 3-11.View

Kim, M. A., Hong, J. S., Ra, M., & Kim, K. (2015). Understanding social exclusion and psychosocial adjustment of North Korean adolescents and young adult refugees in South Korea through Photovoice. Qualitative Social Work, 14(6), 820-841.View