Journal of Public Health Issues and Practices Volume 5 (2021), Article ID: JPHIP-180

https://doi.org/10.33790/jphip1100180Review Article

The Promise of Applying Systems Theory and Integrative Health Approaches to the Current Psychosocial Stress Pandemic

Tamara L. Goldsby1,2*, Michael E. Goldsby1,3, Madisen Haines4, Chiara Marrapodi2, Jesus Saiz Galdos5, Deepak Chopra1,6, Paul J. Mills1.

1Department of Family Medicine and Public Health, University of California, San Diego, United States.

2Department of Psychology, California Institute for Human Science, Encinitas, CA, United States.

3Department of Public Health, University of Louisville, Kentucky, United States.

4Hahn School of Nursing and Health Science, University of San Diego, CA, United States.

5Dept. of Social, Work, and Differential Psychology, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Spain.

6The Chopra Foundation, Carlsbad, CA, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Tamara L. Goldsby, Ph.D., M.A. Department of Family Medicine and Public Health, University of California, San Diego, 9500 Gilman Drive #0725, La Jolla, CA, 92093-0725, United States. E-mail: tgoldsby@health.ucsd.edu

Received date: 31st May, 2021

Accepted date: 10th July, 2021

Published date: 13th July, 2021

Citation:Goldsby, T.L., Goldsby, M.E., Haines, M., Marrapodi, C., Galdos, J.S., Chopra, D., & Mills, P.J. (2021). The Promise of Applying Systems Theory and Integrative Health Approaches to the Current Psychosocial Stress Pandemic. J Pub Health Issue Pract 5(2): 180.

Copyright:©2021, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Abstract

Background: Chronic stress in Western society may currently be characterized as a public health concern at pandemic levels and may be at risk of crossing a tipping point, as evidenced by major societal unrest. While evolutionarily, activation of the body’s sympathetic nervous system (SNS) exists to protect the individual by triggering the ‘fight or flight’ response, this response has been observed to be chronically occurring in a significant number of individuals in Western society. This chronically stressed physiological state has been linked to numerous physical health problems, including cardiovascular disease and diabetes, as well as mental health problems such as depression and anxiety, and behavioral problems such as addictions. When considered in the framework of Systems Theory, the multiple levels of stress – including individual, relationship, and societal levels – may be viewed as interacting and thus compounding features of the system. In this context, this paper also briefly discusses the potential benefits of using Integrative Health treatment approaches as a priority to counter the pandemic’s multiple levels of psychosocial stress.

Objective: This paper strives to examine the pandemic of psychosocial stress in Western society in terms of a Systems Theory and Integrative Health framework.

Conclusion: The next logical step in attempting to avoid and abate more disastrous results of the stress pandemic would include examining effective and promising treatments for chronic stress. Therefore, the present paper recommends the pursuit of extensive research into effective treatments for stress, especially examining treatments that take a whole-person or integrative approach.

Keywords: stress, chronic stress, psychosocial stress, integrative medicine, integrative health, systems theory, whole health.

Introduction

Twelve years ago, an interdisciplinary team of scientists examined the importance of utilizing systems thinking to predict and manage the next global pandemic [1]. This pandemic was realized in 2020 as COVID-19, one of the most devastating global pandemics in the last 100 years [2]. Studies have already documented the severe mental health stress that this pandemic has created [3]. In the face of a potential pandemic, the team of interdisciplinary scientists outlined steps that could be taken to potentially avert or at least abate the many facets of a consequent public health disaster. The ability to gaze down the road to avert potential disasters in public health is one of the factors that makes science a hidden gem in society. The key is not only the prediction, however, but taking the necessary steps that are recommended.

Chronic psychosocial stress is one such looming potential public health disaster which has reached pandemic proportions [4]. While it is widely accepted that stress is a given in Western society, it is challenging to find statistics delineating its actual prevalence, due to its ubiquity. Chronic stress has been found to be extensive in relation to specific careers such as nursing and medicine [5-7] and law enforcement [8,9]. Additionally, stress has been studied extensively in college students [10,11], in regard to work [12] and in relation to gender issues [13]. Western society has become so unaware of this chronic stress that workaholism is viewed as a badge of honor rather than a problematic or even addictive behavior. While many individuals boast regarding working a 60-hour workweek in America, this paradigm has taken a significant toll on us as individuals and as a society and may lead to increasingly adverse outcomes [14].

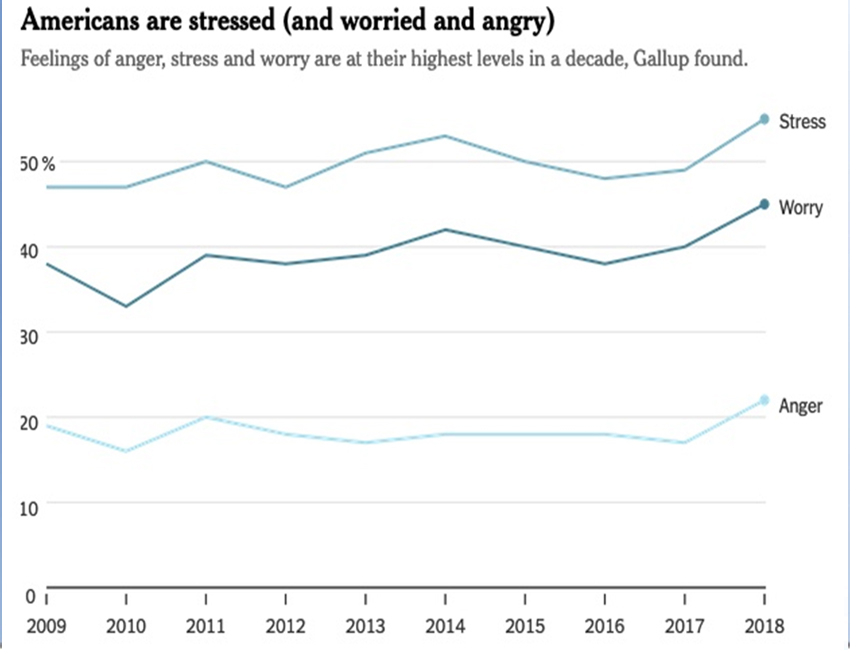

If one asks individuals in Western society if they have stress in their lives, the most likely response is a resounding “Yes”. In fact, a Gallup poll in 2018 found that at least 55% of Americans experienced stress “a lot of the day” compared to 35% globally on the day prior to the poll [15] (see Figure 1). Further, as of 2018, Gallup found that 2017 was the “darkest year for humanity” across the globe, including the highest levels of stress, worry, anger or sadness, and physical pain reported to Gallup since they began the survey in 2005 [15,16]. It is worth noting that this poll was conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, which has further raised global stress levels considerably, and also prior to the severe societal unrest that has surfaced in the U.S. due to abuse of minorities such as African Americans. Regardless of the source of stress, be it work, family, racial trauma, financial, school, economic or political, it is experienced as chronic and unabating by the majority of individuals in Western society. The question is: How do we as individuals and society as a whole combat this further accentuated pandemic of stress? To address this question, it is relevant to examine stress on multiple levels, including its interrelationships and impacts on individual, relationship, and societal, and the manner in which they interact as a system.

Individual Level

To address stress as ‘the elephant in the room’, so to speak, it is relevant to examine our understanding of individual stress in a historical context. Individual stress is widely accepted as endemic and problematic. Chronic stress is an individual level concern; however, it also impacts people at the relationship and societal levels. Chronic stress is interconnected across multiple levels of modern society, creating hidden cyclical patterns that can emerge as seemingly sudden catastrophic events such cancer, divorce, economic failure, and severe societal unrest.

Selye first coined the term ‘stress’ in 1936 and defined it as "the non-specific response of the body to any demand for change” [17,18]. Following numerous experiments, Selye found exposing laboratory animals to varying types of physical and emotional stimuli (be it light, sound, heat, cold, or frustration) the results were the same in terms of pathological changes. These problematic changes included stomach ulcerations, shrinkage of lymphoid tissue, and enlargement of adrenals [19-21]. Selye suggested that stressors are actual or perceived threats to the homeostasis of the organism [17,18].

This interrupted homeostasis may be understood in regard to a physiological response in the human body that has served an evolutionary purpose over time, referred to as the ‘fight or flight’ response. Chronic stress places the body in a continuous state of ‘fight or flight’, engaging the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) in which blood pressure and heart rate are elevated and the body’s immune system becomes less functional. Evolutionarily, this system protected humans by propelling them to fight or flee from danger with the assistance of a burst of cortisol and other neurohormones produced in the body. It could be argued, however, that humans have unknowingly convinced their bodies that this unhealthful and keyed up physiological state is necessary for career and life success. Consequently, Western society has a large proportion of over-worked and chronically stressed individuals, resulting in deleterious physiological effects on the human body, human health, and potentially reverberating through the societal system [22-24].

Exposure to chronic stressors has significant negative neurobiological and psychological effects on the individual. First, as McEwen stated, stress can cause an imbalance in the brain’s neural circuitry that, in turn, affects systemic physiology via neuroendocrine, autonomic, immune, and metabolic mediators [25]. Specifically, stress can lead to neuronal atrophy in frontal cortices (particularly the medial prefrontal cortex), the dorsomedial striatum (caudate), and the hippocampus. Additionally, it also results in neuronal hypertrophy in the dorsolateral striatum (putamen) and amygdala [26,27]. Indeed, research on levels of chronic inflammation measured by inflammatory cytokines and C-reactive protein demonstrates the association between inflammatory dysregulation and stress diagnoses, such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [28].

Further, the effects of chronic stress on humans has been found to not only exist at the physiological level, but have strong associations with mental health challenges, as well. This link between mental health problems and stress has been studied extensively. Specifically, stress shows a significant relationship with depression [29], anxiety [30] and other psychological disorders, including obsessive-compulsive disorder [26]. In addition, acute stress has been linked to antisocial behavior [24]. Recently, in their meta-review, Harvey and colleagues [31] found that the stress of imbalanced job design, occupational uncertainty, and lack of value and respect in the workplace may also contribute to the development of depression and/or anxiety.

While work itself may affect stress levels, lack of employment and the resulting financial burdens have also been associated with significant stress [32]. The American economic downturn and recession in 2008 was shown to result in substantial job loss for workers, which was linked to individual mental health issues (including an increase in mood disorders, depression, and anxiety), as well as physical health problems such as respiratory and cardiovascular disease [33]. Financial stress due to the current pandemic-associated economic downturn is strongly adversely affecting individual stress levels [3], as well as reverberating throughout society in a systemic manner.

Various demographic factors - such as gender and ethnicity - may affect the degree that stressful life events have an effect on mood, depression, and anxiety. In a sample of 5899 American adults, Assari and Lankarani [34] found a stronger association between stressful life events and major depressive episodes for white men as compared to African American men, but no difference in regard to race for women. Thus, while a potential resiliency factor may exist for African American men versus women, it is likely that other factors affected this surprising result, which needs to be further investigated. Racial discrimination is clearly a stressor for minority populations, especially in the U.S. [35,36]. There are protective factors, though, that assist populations dealing with race-related stress, including social support [37]. Additionally, family-centered programs developed for African Americans provide a stress-buffering effect for this population, especially in regard to couple relationships [38].

Larrieu and Sandi [39] addressed the issue of social rank as a mediator of stress-induced depressive behavior and found that individuals in high dominance positions that might lose rank, key resources, or perceived rewards were particularly at risk for the development of chronic stress-induced depressive behavior. The role that neurobiological mediators may play in the interface between chronic stress and the development of mental health problems has also been examined by Maldonado and colleagues [40], who showed that the relationship between acculturative stress and salivary inflammation indicated risk for anxiety in Latino samples. Additionally, Tafet [41] described the possible interaction of functional changes in certain limbic structures and changes in different monoaminergic systems on stress and depression.

Self-efficacy has also been found to be related to reduced stress levels. One study examining three countries (Germany, Russia, and China), found self-efficacy as a mediator of the effects of daily stressors on mental health, with superior effect sizes for well-being compared to depression. Integrative Health (IH) techniques may also assist in the reduction of stress levels and improve self-efficacy, including in high-stress work such as caregiving. In fact, meditation has been found to increase self-efficacy in caregivers [42,43]. Techniques such as Tai Chi also show relationships with improved self-efficacy [44,45]. Moreover, mantrum repetition was found to foster self-efficacy and the management of PTSD [46]. Additionally, yoga was discovered to enhance self-efficacy in stressed individuals [47] and improve self-efficacy, anxiety, and wellbeing in a population of older adults [48].

While the World Health Organization’s (WHO) guidelines [49] for attempting to manage stress in various conditions include strategies such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and relaxation techniques, among others, it is certainly not a ‘one size fits all’ scenario regarding handling stress. Li and colleagues [50] conducted a nine-year longitudinal study in the workplace to study the use of stress management interventions (SMI) and found that the psychotherapeutic techniques of cognitive-behavioral therapy and psychodynamic therapy showed promise in treating individual stress. This study found that these psychotherapeutic techniques were effective in improving stress management abilities (a reduction of perceived stress reactivity) and additionally demonstrated a tendency toward a reduction of psychosocial work stress and an improvement in mental health (depression and anxiety). While this is encouraging a substantial number of individuals are not interested in undergoing psychotherapy for their stress. Thus, it is necessary for society and individuals to have a toolbox of potential stress treatments.

Integrative Health is a wholistic term used to describe the use of complementary and alternative medicine approaches to create “a state of well-being in body, mind, and spirit that reflects aspects of the individual, community, and population.” [51,52]. There are many Integrative Health techniques which have shown promise in easing stress and anxiety, such as yoga [53,54], meditation [55-57] and sound healing methods [58-60]. Moreover, Integrative Health presents a promising approach termed Whole Systems Medicine, which focuses on increasing well-being utilizing a combination of complementary medicine techniques [61,62]. Integrative Medicine tends to take a positive psychology stance in the treatment of depression and stress, including interventions that assist in the promotion of well-being [63,64]. This view addresses the human body as a system rather than addressing merely a problematic symptom such as stress. Due to being in its infancy, this approach is not yet widely accepted in the Western medicine community, however, more research is important to explore the potential healing effects of these combined therapies.

Relationship Level

A wholistic or systems approach is also appropriate when considering that chronic stress not only affects the individual, but also affects interpersonal relationships. Indeed, one’s stress not only carries into marriage and family life, but into friendship and work relationships, as well. Moreover, unfortunately children are also affected by chronic stress, due to stressed parents and unrealistic school demands. Further, patterns of chronic stress in childhood may carry into adulthood and this stressed out state may very well continue as the individual progresses through their life [65,66].

Importantly, the individual does not exist in a bubble, but is interdependent with his/her environment. For many, a great deal of daily life is spent in a work setting. Providing for the needs of self and family is necessary and when employment is merely for financial need, rather than viewed as meaningful and enjoyable, stress may be increased exponentially. Indeed, even in meaningful or enjoyable work, it may be challenging to avoid pitfalls and stressors such as over-commitment, office politics, personality conflicts, and tight deadlines.

The worker’s internal conflict felt by the tug of family life may present challenges in this precarious balance. Once work time spills over into family time, this balance tips the stress scales even further. It may translate into a need for continuous ‘checking in’ with oneself through self-examination and with one’s romantic partner via candid discussions to reestablish balance in the relationship and homeostasis in the relationship system.

There are aspects of marriage and family life that may be affected by this precarious balancing act [67-70]. On the level of romantic relationships, partners may feel slighted and hurt when work appears to take priority over or impede the couple’s relationship. Further, a romantic partner’s work stress often spills into the relationship, which may result in the worker being easily annoyed or angered, or perhaps emotionally withdraw completely in order to decompress from the day’s stressors and entanglements. Much as the spouse may try to be understanding, hurt feelings are oftentimes impossible to avoid. The exhausted individual may return home hoping for quiet and solitude; however, the romantic partner may desire quality time and togetherness. This balancing act may get even more complicated when both partners work outside the home and attempt to juggle their given stressors with the desire to bond with their partner.

The challenges that occur within couples due to the interference of work on marital and family life has been called work-to-family conflict and has been found to have a negative association with marital satisfaction in couples [70]. In addition, this negative association is further amplified when there is also family-to-work conflict, meaning that family demands also encroach on work time [70]. Further complication of this scenario occurs when the couple has children. The child naturally desires and needs time with parents while parents may be too exhausted and stressed to provide quality parenting time.

In addition to relationship challenges, financial stress may place a heavy burden on romantic partners. Financial stress has been linked to individual health problems [71] and has also been examined in the family system. This scenario has been termed the Family Stress Model and recognizes the toll of financial stress on the family, which in turn has been linked to increased conflict in the couple, parental distress, harsh parenting, and behavior problems in children [72]. In addition, the Sociocultural Family Stress Model (SFS) goes further to include cultural and ethnic considerations of additional stress on families, with this model especially intended for particular stress that low socio-economic African American families endure [73]. It has been especially studied in lower-income families and reflects the underlying – and seemingly obvious – strain involved in the scenario of living paycheck-to-paycheck. This stress may include food insecurity and the concern not only regarding the ability to pay monthly bills and expenses, but the very ability to provide basic necessities for the family unit such as food and housing. This extreme end of the financial spectrum exists in far greater numbers than is often recognized. In fact, according to the U.S. government’s 2017 Census report, 12.3% of Americans existed at or below the poverty line [74]. However, even when financial insecurity is not this extreme, the burden of family financial woes – including massive credit card debt and living beyond one’s means – can have a serious impact on the degree of stress in the family.

Certainly, when half of the marital couple team is feeling overly stressed, the romantic partner is affected. Further, the romantic partner’s own challenges – such as addictions or physical or mental health challenges – may place an additional burden of stress on the relationship, with stress further amplified when any of these challenges exist in their children.

Viewing the family as a system is useful in this regard in understanding the interaction and interconnectedness of family members. In Family Systems Theory [75], Bowen posits that the family interacts as a system, in which each member has a particular role to play in the system. Much like a wind chime, the actions of one member affect the feelings and actions of another and each member may take on a specific role, in the manner of a play being performed.

The analogy of a wind chime may be useful when applied to various aspects of the individual’s life in relation to stress. With the individual at the center of the wind chime, work may be one branch of the chime; one’s spouse may be another; children another; finances, physical and emotional health (of self and family) are another; and so on. Thus, the wind chime may be relatively quiet and steady for a period of time until the stormy winds of stress - due to work, financial woes, and so forth - kick up to a high velocity and rattle the chime.

Moreover, systems theory may be characterized as numerous wind chimes in an individual’s life which are lined up and affecting each other. For instance, one’s boss has her own wind chime of family, relationships, and work. At certain times, the family arm of her wind chime creates personal stress for her, thus spilling over into the work branch of her chime. This in turn affects the work chimes of her employee, which the employee carries out to his/her own family. Considering the numerous wind chimes of each individual’s life in this manner assists in viewing the entire system, in which a domino effect may be considered to occur.

Societal Level

On the societal level, stress impacts people in a variety of ways, including financially. Societal economic factors including economic downturns often create a domino effect. For instance, the 2008 economic recession in the U.S. resulted in reduced hospital budgets and spending, translating into reduction in healthcare facilities and medical supply shortages [76]. This placed additional stress on the hospital and healthcare system itself including healthcare workers as well as patients, as they struggled to maintain health in a challenging economy [76]. Thus, a downturn in an economy presents a cyclic challenge and may result in greater numbers of hospitalizations due to individuals who are unable to afford healthcare and who wait until they are in dire need, ending up in the hospital’s emergency room, placing additional stress and strain on the system.

Health insurance coverage is a societal issue that has been debated extensively in recent years and lack of health insurance can be a tremendous individual and societal stressor. Importantly, medical insurance coverage has been linked to financial security, access to – and utilization of – care, management of chronic disease, improved well-being and reported health, as well as reduced mortality rates, according to an article in the New England Journal of Medicine [77]. Conversely, lack of health insurance has been linked to self-reported physical and mental health challenges [78,79]. Additionally, healthcare costs themselves may be a stressor to the individual and to the societal system, even with what may be considered adequate health insurance coverage.

In addition to the societal financial burden of healthcare costs, work-related stress itself places a large financial burden on many countries. In a study examining several European countries, as well as Canada and Australia, work-related stress was found to cost between US $221 million and $187 billion in 2014, depending upon the country. The majority of the financial losses were due to lost productivity and also included healthcare costs [80].

Additionally, factors such as climate change may increase societal stress and place increased financial burdens on individuals and communities. Climate change’s negative impact on farming has been demonstrated the world over, from Madagascar to the American Midwest, for which farmers and the surrounding communities which they supply are experiencing significant adverse effects of climate change. Even societies which have historically been resilient with regard to stress, such as individuals living in the Ganges Delta area of Bangladesh and India (prone to floods, cyclones, and droughts), have shown issues with adaptation when pushed beyond their limits. Such environmental concerns have placed increased stress on these societies due to the dependence of their livelihoods on agricultural lands and the increasing instability of these farmlands [81]. There are certain types of farmers who appear to fare better than others with regard to climate change, including those characterized as ‘environmentalist’ who maintain a higher awareness of the changing earth conditions [82]. Additionally, exposure to information and knowledge appears to change farmers’ perceptions regarding climate change and affords them the ability to make necessary changes, as was found for farmers in Chile [83].

Access to knowledge and information regarding challenging or potentially dire circumstances may empower societies and individuals, which may in turn lower stress levels to a certain degree. In fact, empowerment programs (including those that aim to increase knowledge and skills) geared toward groups that experience discrimination (due to gender, ethnicity, disability, and so on) may assist in tempering stress levels [84-86].

Other societal factors associated with feelings of disempower ment may lead to stress, such as living in an inner city. Lower income inner city neighborhoods tend to have increased crime, noise pollution, and lower quality of schools – stressors for individuals residing in these areas. However, merely walking past a green lot in an inner city neighborhood has been found to decrease heart rate significantly, demonstrating that exposure to green spaces may help decrease stress [87]. Thus, while inner city life appears to place an additional stress on inhabitants, programs involving increased exposure to nature and greenery may assist somewhat in the reduction of stress levels [88]. Moving out of an inner city neighborhood entirely appears to significantly improve individuals’ perspective [89,90].

Many people might consider moving out of the city as not economically feasible. Perhaps, though, residence location may be more of a factor in regard to health and stress level than previously thought. In fact, there are regions that have been termed “The Blue Zones of Happiness” which may support the hypothesized link of a relaxed lifestyle to increased health and longevity. Certain cultures and communities, such as those in Sardinia, Italy, have been found to have exceptionally long-lived citizens and comparatively lower levels of chronic disease [91], as well as lower levels of depressive symptomology and higher levels of perceived wellbeing [92]. It has been theorized that this sociocultural difference may be linked to factors including a slower-paced lifestyle as well as strong community involvement, among other factors [92].

In fact, the health and stress level difference associated with the so-called Blue Zone lifestyle might suggest that a shift from a disease model of health to a model of thriving that takes into account stress levels may provide significant benefits [93]. This model of thriving could be said to be encompassed in the Integrative Health model, including principles such as empowerment, access, and holism [94] and also supports a Systems Theory approach.

Systems Theory and the System of Stress

This paper presents a discussion of stress and its interplay between the individual and relationships, and at the societal level. Examining the interrelationships among these domains using a multifaceted approach may better support our understanding of the far-reaching consequences of stress, individually and collectively [17,18,95].

Systems Theory (ST), or sometimes called Systems Thinking, is one such multifactorial approach that has been proven effective [96]. Simply put, ST involves examining a concept in regard to its interrelated aspects and features. ST has been applied to many disciplines, including biology, medicine [97-100], health systems [101], psychology [102], social policy [103], public health [1,104], [105], education [106], and economics [107].

ST describes the manner in which the natural world and manmade systems are interconnected, producing what may appear to be unexpected events. These unanticipated events emerge from much smaller events that occur over time, creating hidden interconnected feedback loops that produce dynamic cycles or patterns [108]. However, these events do not always lead to problems. In many cases, these cycles and patterns are part of the system’s natural ability to maintain balance and correct issues to avoid system failure. In fact, natural systems such as the human body are capable of self-repair through an intricate set of mechanistic interactions that work together to fix system glitches. However, if numerous human mechanisms are disrupted, the system may decay into disorder, leading to diseases such as cancer and cardiovascular disease as the system is unable to maintain balance. This system of homeostasis occurs in various systems (both natural and manmade) including relationships, communities, the environment, economies, and so on, and at times may involve a precarious balance. Long-term imbalance in the system may create a tipping point that accelerates the decay of the system, which may eventually result in complete system collapse, unforeseen to the preponderance of the population.

The ST approach considers the linkages between the effects of accumulated stressors across a spectrum [109]. ST approaches accept that the effects of stress are not the result of a single factor, rather stress has multi-system effects. These effects are experienced individually on physiological, mental, and emotional levels [109]. Furthermore, ST is inclusive of wider effects such as environmental and societal linkages. Indeed, ST adopts a dynamic rather than linear approach to world problems. It is inclusive of various systems and extends beyond cognitive ideology alone. Rather, it provides a valuable wholistic approach to real world applications.

An open system approach supports the dynamic response between the internal and external environment through bio-feedback loops. This is evident within the biological cycle of stress in the mammalian body. Inflammation has been identified as the pathway between psychosocial stress and health [110]. Stress activates the sympathetic nervous system and hypothalamus pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis. Alterations in HPA axis stress reactivity contribute to allostatic load and have been implicated in ailments including atopic dermatitis, depression, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and childhood cancer [110].

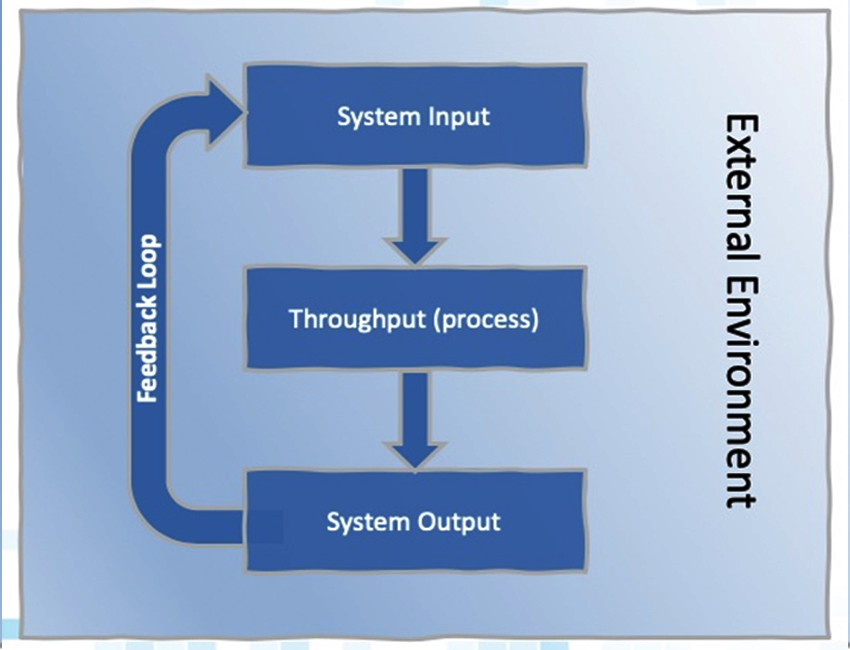

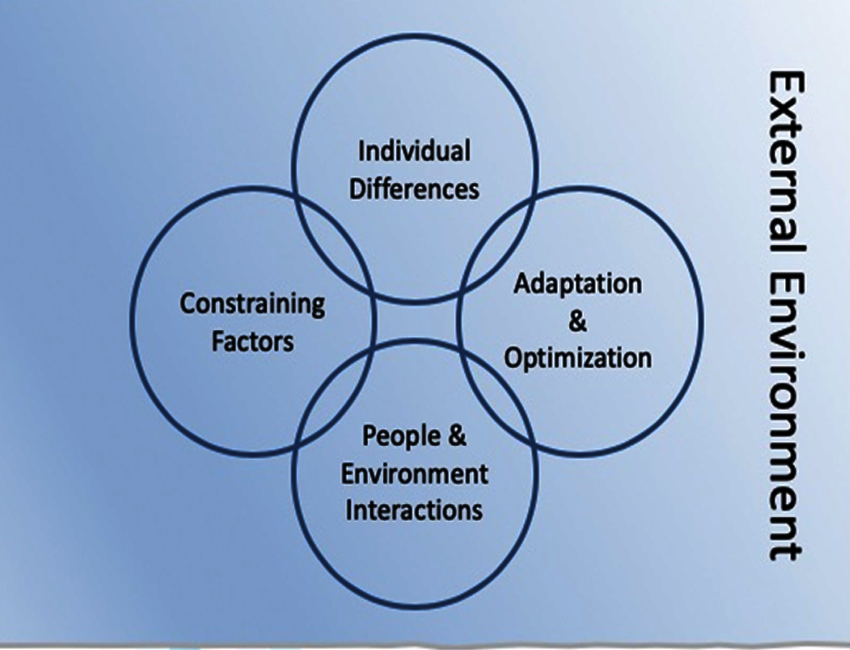

All open systems are comprised of three main components: input, throughput (process), and output [96] (see Figure 2). These interrelationships are a key concept in ST. This interweaving relational web suggests interdependence in contrast to the traditional independent closed system view in which compartmentalization is the norm. As depicted in Figure 3, the interactions between individual factors, environmental factors, constraints, and the ability to adapt and/or optimize are the constituent features of an open system. It further highlights the manner in which this system is embedded within the social, economic, environmental, and societal context within which it resides. This level of complexity poses methodological constraints that are inherently a characteristic of complex systems [96].

As contemporary society becomes more complex, a more refined solution set becomes necessary. Therefore, a call for a change in our thinking and approach is necessary and ST supports this evolution because it is inclusive of the bi-directional environmental and societal links to the individual and collective experience. Adopting this view highlights the effects of stress in society through the lens of an ecological model. Not only does it provide a global view, it is a doorway to providing a whole solution approach to those affected by stress. Examples of ST use in scientific studies abound. For example, a recent pilot study by Rocca and colleagues highlights the manner in which a global meta-analysis of how environmental stressors affect the microbiome [111]. Their findings suggest a more global approach is needed in examining patterns in microbiome response. Additionally, this approach has been successful at identifying the trans-relational trauma effects of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) from veterans to their spouses and offspring [112]. ST supports the accounting of the impact not only on the marital relationship but also the parental subsystem. This provides a richer understanding of the role stress plays in the family unit beyond the individual level alone.

In considering contemporary Western society, the ST approach may be quite beneficial. It is clear that current thinking supports the complexity of experience (ontology) and knowledge (epistemology) embedded in contextual systems (societal, cultural, legal, and so on), natural and/or manmade. This type of thinking supports the understanding of feedback loops between the system and the individual. These feedback loops are dynamic and may be positive or negative (Figure 2). This approach facilitates understanding the complex interplay between microsystem and macrosystem and provides a platform for systematic inquiry. Inherently, systems thinking allows one to assess and investigate through a learning system [113,114].

Thus, ST is appropriate and useful for examining the interconnected system of stress in regard to the individual, relationship, and societal levels. This framework is especially useful when we consider that the system may be teetering toward a tipping point due to multiple system failures.

Sites of Potential System Failures and Solutions

Society is currently displaying signs of potential “system failure” in relation to stress, especially in the U.S. These signs are clear and consistent and are evident at various levels:

- Individual level: The individual may be considered to be at the center of the stress system. Dysfunctional coping methods and symptoms of chronic stress may include addictive behaviors and the worsening of mental health challenges.

- Relationship level: Interpersonal and romantic relationship problems include domestic and sexual violence, as well as high rates of divorce, among other relationship problems.

- Societal level: Economic downturn; increases in healthcare costs; racial and societal inequalities as well as violence against minorities, naturally leading to social unrest; as well as high crime rates and mass shootings.

In present day Western society – and especially in the U.S. – there are fundamental issues of modernity that have likely contributed to the current stress pandemic and current system failures. Specifically, Western society has succumbed to excessive materialism, consumerism, and rampant (or perhaps even toxic) individualism [115]. This unhealthy state of being prioritizes financial rewards and power positions over humanistic psychology, placing individuals on the proverbial hamster wheel in continuous pursuit of the next promotion, expensive automobile, and so on.

The current public health system may be ill-equipped to effectively handle this stress-inducing paradigm, which may be evidenced by epidemics of obesity, substance abuse problems, and mental health challenges, as discussed by the World Health Organization (WHO) [116]. Thus, an integrative framework in public health may begin to offer a solution. Such an Integrative Health framework might consider aspects such as the changing state of science and emergent ethics rather than merely maintaining the status quo in the healthcare system [115]. Moreover, in the Global Happiness and Wellbeing Policy Report 2019, leading wellbeing scientists from around the globe call for a public health and education paradigm shift utilizing an ecosystem focused upon wellbeing and happiness [117].

Perez-Alvarado and colleagues call for just such a paradigm shift in integrative medicine and propose a Five-Sphere Model to address the challenges faced by Western society and allopathic medicine. Their whole person framework addresses the deficiencies in the present system and includes a consideration of Systems Medicine and Systems Biology. Specifically, they present a model emphasizing the interplay and dynamic interdependency between the physical, mental, spiritual and emotional components of the individual. This type of wholistic model is quite relevant to a discussion on stress as it considers the many factors impacting humans and their stress levels rather than assuming a traditional reductionistic view of the individual [118].

Integrative medicine approaches taking a Systems Theory view could benefit by addressing the interplay and interconnectedness of the individual, social, environmental and intergenerational factors to enable wellbeing [119,120]. Additionally, integrative medicine may benefit from systems approaches such as nonlinear dynamic complex systems (NDS) science to address whole systems medicine research [121]. Moreover, an effective integrative medicine approach needs to address health justice issues in public health impacting the individual such as equity, diversity and inclusion [122].

While there are many potential solutions to addressing these sites of system failures, IH endeavors to simultaneously support the creation of wellbeing for the individual and society [51,52]. In the context of Whole Systems Medicine, IH has extensive promise as evidenced by thousands of research studies [61,62].

Discussion

Next Necessary Steps

The stress interaction and connection among individuals, interpersonal relationships, and society may be currently reaching a tipping point. Events of 2020 and 2021, including COVID-19 and racial trauma, have served to bring societal stress to the surface, particularly in the U.S. The authors of the present paper suggest that researchers take the lead in moving toward adopting an ST approach to develop efficacious solutions. Much like the so-called ‘butterfly effect’, making moderate changes at the individual level may reverberate throughout the system and translate into positive changes in the societal system. Thus, addressing stressors and ways to reduce stress should be made a high-level research priority, at least at the individual level. Further, addressing the issue of chronic stress at an in-depth and whole-person level, as characterized by the Integrative Health approach, is additionally called for.

Chronic stress may reasonably be considered at a pandemic level in Western society, particularly in America, with significant negative impact on the individual, relationship, and societal levels. Viewing stress in terms of ST, the interactive effects of stress on these levels becomes clear. Thus, while in-depth discussion of treatments for stress are beyond the scope of the present paper, the next logical step in attempting to avoid and abate more disastrous results of the stress pandemic would include examining effective and promising treatments for chronic stress. Therefore, the present paper recommends the pursuit of extensive research into effective treatments for stress, especially examining treatments that take a whole-person or integrative approach.

Acknowledgments:

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The work was supported by the University of California San Diego’s Center of Excellence for Research and Training in Integrative Health.

Conflict of interests:

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

S. J. Leischow et al., (2008). “Systems Thinking to Improve the Public’s Health,” Am J Prev Med, vol. 35, no. 2 0, pp. S196– S203, doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.05.014.View

“Past Pandemics | Pandemic Influenza (Flu) | CDC,” Jun. 11, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/basics/past-pandemics.html (accessed Jun. 14, 2020).View

C. González-Sanguino et al. (2020). “Mental health consequences during the initial stage of the 2020 Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain,” Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, vol. 87, pp. 172–176, doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.040.View

J. Hassard, K. R. H. Teoh, G. Visockaite, P. Dewe, and T. Cox., (2018). “The cost of work-related stress to society: A systematic review,” J Occup Health Psychol, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 1–17, doi: 10.1037/ocp0000069.View

D. K. Creedy, M. Sidebotham, J. Gamble, J. Pallant, and J. Fenwick., (2017). “Prevalence of burnout, depression, anxiety and stress in Australian midwives: a cross-sectional survey,” BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, vol. 17, no. 1, p. 13, doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-1212-5.View

M. Fawzy and S. A. Hamed, (2017). “Prevalence of psychological stress, depression and anxiety among medical students in Egypt,” Psychiatry Research, vol. 255, pp. 186–194, doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.05.027.View

A.-C. Durand, C. Bompard, J. Sportiello, P. Michelet, and S. Gentile., (2019). “Stress and burnout among professionals working in the emergency department in a French university hospital: Prevalence and associated factors,” Work, vol. 63, no. 1, pp. 57–67, doi: 10.3233/WOR-192908.View

A. F. Allisey, A. J. Noblet, A. D. Lamontagne, and J. Houdmont, (2014). “Testing a Model of Officer Intentions to Quit: The Mediating Effects of Job Stress and Job Satisfaction,” Criminal Justice and Behavior, vol. 41, no. 6, pp. 751–771, Jun. , doi: 10.1177/0093854813509987.View

A. Tyagi and R. Lochan Dhar, (2014). “Factors affecting health of the police officials: mediating role of job stress,” Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, vol. 37, no. 3, pp. 649–664, doi: 10.1108/PIJPSM-12-2013-0128.View

V. K. Nahar et al., (2019). “The prevalence and demographic correlates of stress, anxiety, and depression among veterinary students in the Southeastern United States,” Research in Veterinary Science, vol. 125, pp. 370–373, doi: 10.1016/j. rvsc.2019.07.007.View

R. Beiter et al., (2015). “The prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and stress in a sample of college students,” Journal of Affective Disorders, vol. 173, pp. 90–96, doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.054.View

K. Shoji et al., (2015). “What Comes First, Job Burnout or Secondary Traumatic Stress? Findings from Two Longitudinal Studies from the U.S. and Poland,” PLOS ONE, vol. 10, no. 8, p. e0136730, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136730.View

T. Theorell, A. Hammarström, P. E. Gustafsson, L. M. Hanson, U. Janlert, and H. Westerlund., (2014). “Job strain and depressive symptoms in men and women: a prospective study of the working population in Sweden,” J Epidemiol Community Health, vol. 68, no. 1, pp. 78–82, doi: 10.1136/jech-2012-202294.View

K. Wong, A. H. S. Chan, and S. C. Ngan, (2019). “The Effect of Long Working Hours and Overtime on Occupational Health: A Meta-Analysis of Evidence from 1998 to 2018,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 16, no. 12, Art. no. 12, doi: 10.3390/ijerph16122102.View

N. Chokshi, “Americans Are Among the Most Stressed People in the World, Poll Finds,” The New York Times, Apr. 25, 2019. Accessed: Jun. 14, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www. nytimes.com/2019/04/25/us/americans-stressful.htmlView

N. Chokshi, “It’s Not Just You: 2017 Was Rough for Humanity, Study Finds,” The New York Times, Sep. 12, 2018. Accessed: May 16, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.nytimes. com/2018/09/12/world/humanity-stress-sadness-pain.html View

S. Szabo, M. Yoshida, J. Filakovszky, and G. Juhasz, (2017). “‘Stress’ is 80 Years Old: From Hans Selye Original Paper in 1936 to Recent Advances in GI Ulceration,” Current Pharmaceutical Design, vol. 23, no. 27, pp. 4029–4041, doi: 10 .2174/1381612823666170622110046.View

M. Del Giudice et al., (2018). “What Is Stress? A Systems Perspective,” Integr Comp Biol, vol. 58, no. 6, pp. 1019–1032, doi: 10.1093/icb/icy114.View

G. P. Chrousos, (2009). “The Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal Axis and Immune-Mediated Inflammation,” http://dx.doi. org/10.1056/NEJM199505183322008. https://www.nejm. org/doi/10.1056/NEJM199505183322008 (accessed Aug. 02, 2020).View

G. Fink, (2016). “Eighty years of stress,” Nature, vol. 539, no. 7628, Art. no. 7628, doi: 10.1038/nature20473.View

D. S. Goldstein, (2010). “Adrenal Responses to Stress,” Cell Mol Neurobiol, vol. 30, no. 8, pp. 1433–1440, doi: 10.1007/ s10571-010-9606-9.View

A. Mariotti, (2015). “The effects of chronic stress on health: new insights into the molecular mechanisms of brain–body communication,” Future Sci OA, vol. 1, no. 3, doi: 10.4155/ fso.15.21.View

N. Rohleder, (2014). “Stimulation of Systemic Low-Grade Inflammation by Psychosocial Stress,” Psychosomatic Medicine, vol. 76, no. 3, pp. 181–189, doi: 10.1097/ PSY.0000000000000049.View

S. Bendahan, L. Goette, J. Thoresen, L. Loued-Khenissi, F. Hollis, and C. Sandi, (2017). “Acute stress alters individual risk taking in a time-dependent manner and leads to anti-social risk,” European Journal of Neuroscience, vol. 45, no. 7, pp. 877–885, doi: 10.1111/ejn.13395.View

B. S. McEwen, “Neurobiological and Systemic Effects of Chronic Stress,” Chronic Stress (Thousand Oaks), vol. 1, 2017, Accessed: May 01, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5573220/View

T. G. Adams, B. Kelmendi, C. A. Brake, P. Gruner, C. L. Badour, and C. Pittenger, (2018). “The Role of Stress in the Pathogenesis and Maintenance of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder,” Chronic Stress, vol. 2, p. 2470547018758043, doi: 10.1177/2470547018758043.View

E. Dias-Ferreira et al., (2009). “Chronic Stress Causes Frontostriatal Reorganization and Affects Decision-Making,” Science, vol. 325, no. 5940, pp. 621–625, doi: 10.1126/ science.1171203.View

M. E. Renna, M. S. O’Toole, P. E. Spaeth, M. Lekander, and D. S. Mennin, (2018). “The association between anxiety, traumatic stress, and obsessive-compulsive disorders and chronic inflammation: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” Depress Anxiety, vol. 35, no. 11, pp. 1081–1094, doi: 10.1002/da.22790.View

R. C. Kessler., (1997). “The Effects of Stressful Life Events on Depression,” Annual Review of Psychology, vol. 48, no. 1, pp. 191–214, doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.191.View

R. Finlay-Jones and G. W. Brown, (1981). “Types of stressful life event and the onset of anxiety and depressive disorders,” Psychological Medicine, vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 803–815, doi: 10.1017/S0033291700041301.View

S. B. Harvey et al., (2017). “Can work make you mentally ill? A systematic meta-review of work-related risk factors for common mental health problems,” Occup Environ Med, vol. 74, no. 4, pp. 301–310, doi: 10.1136/oemed-2016-104015.View

N. Mucci, G. Giorgi, M. Roncaioli, J. Fiz Perez, and G. Arcangeli, (2016). “The correlation between stress and economic crisis: a systematic review,” Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat, vol. 12, pp. 983– 993, doi: 10.2147/NDT.S98525.View

N. Mucci, G. Giorgi, S. De Pasquale Ceratti, J. Fiz-Pérez, F. Mucci, and G. Arcangeli, (2016). “Anxiety, Stress-Related Factors, and Blood Pressure in Young Adults,” Front Psychol, vol. 7, doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01682.View

S. Assari and M. M. Lankarani., (2016). “Association Between Stressful Life Events and Depression; Intersection of Race and Gender,” J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 349–356, doi: 10.1007/s40615-015-0160-5.View

Y. Lanier, M. S. Sommers, J. Fletcher, M. Y. Sutton, and D. D. Roberts, (2017). “Examining Racial Discrimination Frequency, Racial Discrimination Stress, and Psychological Well-Being Among Black Early Adolescents,” Journal of Black Psychology, vol. 43, no. 3, pp. 219–229, doi: 10.1177/0095798416638189.View

L. Polanco-Roman, A. Danies, and D. M. Anglin, (2016). “Racial discrimination as race-based trauma, coping strategies, and dissociative symptoms among emerging adults,” Psychol Trauma, vol. 8, no. 5, pp. 609–617, doi: 10.1037/tra0000125.View

M. O. Odafe, T. K. Salami, and R. L. Walker, (2017). “Race-related stress and hopelessness in community-based African American adults: Moderating role of social support,” Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol, vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 561–569, doi: 10.1037/cdp0000167.View

A. W. Barton, S. R. H. Beach, C. M. Bryant, J. A. Lavner, and G. H. Brody, (2018). “Stress spillover, African Americans’ couple and health outcomes, and the stress-buffering effect of family-centered prevention,” J Fam Psychol, vol. 32, no. 2, pp. 186–196, doi: 10.1037/fam0000376.View

T. Larrieu and C. Sandi., (2018). “Stress-Induced Depression: Is Social Rank a Predictive Risk Factor?,” BioEssays, vol. 40, no. 7, p. 1800012, doi: 10.1002/bies.201800012.View

A. Maldonado, A. Preciado, M. Buchanan, K. Pulvers, D. Romero, and K. D’Anna-Hernandez, (2018). “Acculturative stress, mental health symptoms, and the role of salivary inflammatory markers among a Latino sample,” Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 277–283, doi: 10.1037/cdp0000177.View

G. E. Tafet, (2017). “Psychoneuroendocrinological and Cognitive Interactions in the Interface Between Chronic Stress and Depression,” in Psychiatry and Neuroscience Update - Vol. II: A Translational Approach, P. Á. Gargiulo and H. L. Mesones-Arroyo, Eds. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 161–172. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-53126-7_13.View

S. P. Pandya., (2019). “Meditation Program Enhances Self-efficacy and Resilience of Home-based Caregivers of Older Adults with Alzheimer’s: A Five-year Follow-up Study in Two South Asian Cities,” Journal of Gerontological Social Work, vol. 62, no. 6, pp. 663–681, doi: 10.1080/01634372.2019.1642278.View

D. Oman, T. A. Richards, J. Hedberg, and C. E. Thoresen, (2008). “Passage Meditation Improves Caregiving Self-efficacy among Health Professionals: A Randomized Trial and Qualitative Assessment,” J Health Psychol, vol. 13, no. 8, pp. 1119–1135, doi: 10.1177/1359105308095966.View

Y. Tong, L. Chai, S. Lei, M. Liu, and L. Yang, (2018). “Effects of Tai Chi on Self-Efficacy: A Systematic Review,” Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. https://www. hindawi.com/journals/ecam/2018/1701372/ (accessed Sep. 01, 2020).View

G. Y. Yeh, C. W. Chan, P. M. Wayne, and L. Conboy, (2016). “The Impact of Tai Chi Exercise on Self-Efficacy, Social Support, and Empowerment in Heart Failure: Insights from a Qualitative Sub-Study from a Randomized Controlled Trial,” PLOS ONE, vol. 11, no. 5, p. e0154678, doi: 10.1371/journal. pone.0154678.View

D. Oman and J. E. Bormann, (2015). “Mantram repetition fosters self-efficacy in veterans for managing PTSD: A randomized trial,” Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 34–45, doi: 10.1037/a0037994.View

Z. L. Hewett, K. L. Pumpa, C. A. Smith, P. P. Fahey, and B. S. Cheema, (2018). “Effect of a 16-week Bikram yoga program on perceived stress, self-efficacy and health-related quality of life in stressed and sedentary adults: A randomised controlled trial,” Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 352–357, doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2017.08.006.View

K. B. Bonura and G. Tenenbaum, (2014). “Effects of Yoga on Psychological Health in Older Adults,” Journal of Physical Activity and Health, vol. 11, no. 7, pp. 1334–1341, doi: 10.1123/ jpah.2012-0365.View

“WHO | WHO guidelines on conditions specifically related to stress,” WHO. https://www.who.int/mental_health/ emergencies/stress_guidelines/en/ (accessed Jun. 27, 2020).View

J. Li et al., (2017). “Long-Term Effectiveness of a Stress Management Intervention at Work: A 9-Year Follow-Up Study Based on a Randomized Wait-List Controlled Trial in Male Managers,” BioMed Research International, Oct. 18, . https:// www.hindawi.com/journals/bmri/2017/2853813/ (accessed Jun. 27, 2020).View

C. M. Witt et al., (2017). “Defining Health in a Comprehensive Context: A New Definition of Integrative Health,” Am J Prev Med, vol. 53, no. 1, pp. 134–137, doi: 10.1016/j. amepre.2016.11.029.View

D. Melchart, (2018). “From Complementary to Integrative Medicine and Health: Do We Need a Change in Nomenclature?,” Complement Med Res, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 76–78, doi: 10.1159/000488623.View

N. P. Gothe, R. K. Keswani, and E. McAuley, (2016). “Yoga practice improves executive function by attenuating stress levels,” Biological Psychology, vol. 121, pp. 109–116, doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2016.10.010.View

M. C. Pascoe, D. R. Thompson, and C. F. Ski, (2017). “Yoga, mindfulness-based stress reduction and stress-related physiological measures: A meta-analysis,” Psychoneuroendocrinology, vol. 86, pp. 152–168, doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.08.008.View

T. Dada et al., (2018). “Mindfulness Meditation Reduces Intraocular Pressure, Lowers Stress Biomarkers and Modulates Gene Expression in Glaucoma: A Randomized Controlled Trial,” Journal of Glaucoma, vol. 27, no. 12, pp. 1061–1067, doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000001088.View

E. A. Hoge et al., (2018). “The effect of mindfulness meditation training on biological acute stress responses in generalized anxiety disorder,” Psychiatry Research, vol. 262, pp. 328–332, doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.01.006.View

B. S. Oken et al., (2017). “Meditation in Stressed Older Adults: Improvements in Self-Rated Mental Health Not Paralleled by Improvements in Cognitive Function or Physiological Measures,” Mindfulness, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 627–638, doi: 10.1007/s12671-016-0640-7.View

T. L. Goldsby, M. E. Goldsby, M. McWalters, and P. J. Mills, (2016). “Effects of Singing Bowl Sound Meditation on Mood, Tension, and Well-being: An Observational Study,” J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med, doi: 10.1177/2156587216668109.View

J. M. Landry, (2013). “Physiological and Psychological Effects of a Himalayan Singing Bowl in Meditation Practice: A Quantitative Analysis,” American Journal of Health Promotion, vol. 28, no. 5, pp. 306–309, doi: 10.4278/ajhp.121031- ARB-528.View

F. Wepner, J. Hahne, A. Teichmann, G. Berka-Schmid, A. Hördinger, and M. Friedrich, (2008). “[Treatment with crystal singing bowls for chronic spinal pain and chronobiologic activities - a randomized controlled trial].,” Forsch Komplementmed, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 130–137, doi: 10.1159/000136571.View

M. Hunt, F. Al-Braiki, S. Dailey, R. Russell, and K. Simon, (2018). “Mindfulness Training, Yoga, or Both? Dismantling the Active Components of a Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Intervention,” Mindfulness, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 512–520, doi: 10.1007/s12671-017-0793-z.View

P. J. Mills, S. Patel, T. Barsotti, C. T. Peterson, and D. Chopra, (2017). “Advancing Research on Traditional Whole Systems Medicine Approaches,” J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med, vol. 22, no. 4, pp. 527–530, doi: 10.1177/2156587217745408.View

C. Chaves, I. Lopez-Gomez, G. Hervas, and C. Vazquez, (2019). “The Integrative Positive Psychological Intervention for Depression (IPPI-D),” J Contemp Psychother, vol. 49, no. 3, pp. 177–185, doi: 10.1007/s10879-018-9412-0.View

H. Wahbeh, (2018). “Internet Mindfulness Meditation Intervention (IMMI) Improves Depression Symptoms in Older Adults,” Medicines, vol. 5, no. 4, Art. no. 4, doi: 10.3390/ medicines5040119.View

D. V. Papero, (2017). “Trauma and the Family: A Systems-oriented Approach,” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, vol. 38, no. 4, pp. 582–594, doi: 10.1002/ anzf.1269.View

A. S. Masarik and R. D. Conger, (2017). “Stress and child development: a review of the Family Stress Model,” Current Opinion in Psychology, vol. 13, pp. 85–90, doi: 10.1016/j. copsyc.2016.05.008.View

J. A. Simpson and W. Steven Rholes, (2017). “Adult Attachment, Stress, and Romantic Relationships,” Curr Opin Psychol, vol. 13, pp. 19–24, doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.04.006.View

S. M. Flood and K. R. Genadek, (2016). “Time for Each Other: Work and Family Constraints Among Couples,” Journal of Marriage and Family, vol. 78, no. 1, pp. 142–164, doi: 10.1111/ jomf.12255.View

M. K. Falconier, F. Nussbeck, G. Bodenmann, H. Schneider, and T. Bradbury, (2015). “Stress From Daily Hassles in Couples: Its Effects on Intradyadic Stress, Relationship Satisfaction, and Physical and Psychological Well-Being,” Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, vol. 41, no. 2, pp. 221–235, doi: 10.1111/ jmft.12073.View

K. L. Minnotte, M. C. Minnotte, and J. Bonstrom, (2015).“Work– Family Conflicts and Marital Satisfaction Among US Workers: Does Stress Amplification Matter?,” J Fam Econ Iss, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 21–33, doi: 10.1007/s10834-014-9420-5.View

B. R. Whitehead and C. S. Bergeman, (2017). “The effect of the financial crisis on physical health: Perceived impact matters,” J Health Psychol, vol. 22, no. 7, pp. 864–873, doi: 10.1177/1359105315617329.View

T. K. Neppl, J. M. Senia, and M. B. Donnellan, (2016). “Effects of economic hardship: Testing the family stress model over time,” Journal of Family Psychology, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 12–21, doi: 10.1037/fam0000168.View

S. M. Smith and A. M. Landor, (2018). “Toward a Better Understanding of African American Families: Development of the Sociocultural Family Stress Model,” Journal of Family Theory & Review, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 434–450, doi: 10.1111/ jftr.12260.View

“Semega et al. - Income and Poverty in the United States 2018. pdf.” Accessed: Jun. 27, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www. census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2019/ demo/p60-266.pdfView

M. Bowen, Family Therapy in Clinical Practice, 1 edition. Princeton, NJ: Jason Aronson, 1993.View

N. Mucci, G. Giorgi, M. Roncaioli, J. Fiz Perez, and G. Arcangeli, (2016). “The correlation between stress and economic crisis: a systematic review,” Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat, vol. 12, pp. 983– 993, doi: 10.2147/NDT.S98525.View

B. D. Sommers, A. A. Gawande, and K. Baicker, (2017). “Health Insurance Coverage and Health — What the Recent Evidence Tells Us,” N Engl J Med, vol. 377, no. 6, pp. 586–593, doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1706645.View

K. Simon, A. Soni, and J. Cawley, (2017). “The Impact of Health Insurance on Preventive Care and Health Behaviors: Evidence from the First Two Years of the ACA Medicaid Expansions,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 390–417, doi: 10.1002/pam.21972.View

J. Schaller and A. H. Stevens, (2015). “Short-run effects of job loss on health conditions, health insurance, and health care utilization,” Journal of Health Economics, vol. 43, pp. 190–203, doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2015.07.003.View

J. Hassard, K. R. H. Teoh, G. Visockaite, P. Dewe, and T. Cox, (2018). “The cost of work-related stress to society: A systematic review,” Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 1–17, doi: 10.1037/ocp0000069.View

S. Ayeb-Karlsson, K. van der Geest, I. Ahmed, S. Huq, and K. Warner, (2016). “A people-centred perspective on climate change, environmental stress, and livelihood resilience in Bangladesh,” Sustain Sci, vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 679–694, doi: 10.1007/s11625-016-0379-z.View

J. J. Hyland, D. L. Jones, K. A. Parkhill, A. P. Barnes, and A. P. Williams, (2016). “Farmers’ perceptions of climate change: identifying types,” Agric Hum Values, vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 323– 339, doi: 10.1007/s10460-015-9608-9.View

L. Roco, A. Engler, B. E. Bravo-Ureta, and R. Jara-Rojas, (2015). “Farmers’ perception of climate change in mediterranean Chile,” Reg Environ Change, vol. 15, no. 5, pp. 867–879, doi: 10.1007/s10113-014-0669-x.View

F. E. Balcazar, J. Kuchak, S. Dimpfl, V. Sariepella, and F. Alvarado, (2014). “An empowerment model of entrepreneurship for people with disabilities in the United States,” Psychosocial Intervention, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 145–150, doi: 10.1016/j. psi.2014.07.002.View

R. Travis and T. G. J. Leech, (2014). “Empowerment-Based Positive Youth Development: A New Understanding of Healthy Development for African American Youth,” Journal of Research on Adolescence, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 93–116, doi: 10.1111/jora.12062.View

S. G. Turner and T. M. Maschi, (2015). “Feminist and empowerment theory and social work practice,” Journal of Social Work Practice, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 151–162, doi: 10.1080/02650533.2014.941282.View

E. C. South, B. C. Hohl, M. C. Kondo, J. M. MacDonald, and C. C. Branas, (2018). “Effect of Greening Vacant Land on Mental Health of Community-Dwelling Adults: A Cluster Randomized Trial,” JAMA Netw Open, vol. 1, no. 3, pp. e180298–e180298, doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0298.View

R. Berto, (2014). “The Role of Nature in Coping with Psycho-Physiological Stress: A Literature Review on Restorativeness,” Behavioral Sciences, vol. 4, no. 4, Art. no. 4, doi: 10.3390/ bs4040394.View

J. Darrah and S. DeLuca, (2014). “‘Living Here has Changed My Whole Perspective’: How Escaping Inner-City Poverty Shapes Neighborhood and Housing Choice,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 350–384, doi: 10.1002/pam.21758.View

G. Karandinos, L. K. Hart, F. M. Castrillo, and P. Bourgois, (2014). “The Moral Economy of Violence in the US Inner City,” Curr Anthropol, vol. 55, no. 1, pp. 1–22, doi: 10.1086/674613.View

M. Poulain et al., (2004). “Identification of a geographic area characterized by extreme longevity in the Sardinia island: the AKEA study,” Experimental Gerontology, vol. 39, no. 9, pp. 1423–1429, doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2004.06.016.View

P. K. Hitchcott, M. C. Fastame, and M. P. Penna, (2018). “More to Blue Zones than long life: positive psychological characteristics,” Health, Risk & Society, vol. 20, no. 3–4, pp. 163–181, doi: 10.1080/13698575.2018.1496233.View

B. R. Doolittle, (2020). “The Blue Zones as a Model for Physician Well-Being,” The American Journal of Medicine, vol. 133, no. 6, pp. 653–654, doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.12.045.View

B. Barrett et al., (2003). “Themes of Holism, Empowerment, Access, and Legitimacy Define Complementary, Alternative, and Integrative Medicine in Relation to Conventional Biomedicine,” The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, vol. 9, no. 6, pp. 937–947, doi: 10.1089/107555303771952271.View

N. Mucci, G. Giorgi, M. Roncaioli, J. Fiz Perez, and G. Arcangeli, (2016). “The correlation between stress and economic crisis: a systematic review,” Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat, vol. 12, pp. 983– 993, doi: 10.2147/NDT.S98525.View

B. V. Adkoli and S. C. Parija, (2019). “Systems approach in medical education: The thesis, antithesis, and synthesis,” Trop Parasitol, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 3–6, doi: 10.4103/tp.TP_7_19.View

A. O. Goushcha, T. O. Hushcha, L. N. Christophorov, and M. Goldsby, (2014). “Self-Organization and Coherency in Biology and Medicine,” Open Journal of Biophysics, vol. 04, p. 119, doi: 10.4236/ojbiphy.2014.44014.View

S. Greenblum, P. J. Turnbaugh, and E. Borenstein, (2012). “Metagenomic systems biology of the human gut microbiome reveals topological shifts associated with obesity and inflammatory bowel disease,” PNAS, vol. 109, no. 2, pp. 594– 599, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116053109.View

D. Zakim, (2011). “Reductionism in medical science and practice,” QJM, vol. 104, no. 2, pp. 173–174, doi: 10.1093/ qjmed/hcq173.View

A. C. Ahn, M. Tewari, C.-S. Poon, and R. S. Phillips., (2006). “The Limits of Reductionism in Medicine: Could Systems Biology Offer an Alternative?,” PLoS Med, vol. 3, no. 6, doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030208.View

D. Bishai, L. Paina, Q. Li, D. H. Peters, and A. A. Hyder., (2014). “Advancing the application of systems thinking in health: why cure crowds out prevention,” Health Research Policy and Systems, vol. 12, no. 1, p. 28, doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-12-28.View

B. S. Oken, I. Chamine, and W. Wakeland, (2015). “A systems approach to stress, stressors and resilience in humans,” Behavioural Brain Research, vol. 282, pp. 144–154, doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.12.047.View

J. Hassard, K. R. H. Teoh, G. Visockaite, P. Dewe, and T. Cox, (2018). “The cost of work-related stress to society: A systematic review,” Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 1–17, doi: 10.1037/ocp0000069.View

S. Chughtai and K. Blanchet, (2017). “Systems thinking in public health: a bibliographic contribution to a meta-narrative review,” Health Policy Plan, vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 585–594, doi: 10.1093/heapol/czw159.View

D. De Savigny, T. Adam, Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, and World Health Organization, Eds., Systems thinking for health systems strengthening. Geneva: Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research ; World Health Organization, 2009.View

D. S. Coffey et al., (2017). “A Multifaceted Systems Approach to Addressing Stress Within Health Professions Education and Beyond,” NAM Perspectives, doi: 10.31478/201701e.View

M. Kalia, (2002). “Assessing the economic impact of stress - The modern day hidden epidemic,” Metabolism, vol. 51, no. 6, pp. 49–53, doi: 10.1053/meta.2002.33193.View

D. Cabrera, L. Cabrera, and E. Powers, (2015). “A Unifying Theory of Systems Thinking with Psychosocial Applications,” Systems Research and Behavioral Science, vol. 32, no. 5, pp. 534–545, doi: 10.1002/sres.2351.View

D. S. Coffey et al., (2017). “A Multifaceted Systems Approach to Addressing Stress Within Health Professions Education and Beyond,” NAM Perspectives, vol. 7, no. 1, doi: 10.31478/201701e.View

X. Chen et al., (2017). “HPA-axis and inflammatory reactivity to acute stress is related with basal HPA-axis activity,” Psychoneuroendocrinology, vol. 78, pp. 168–176, doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.01.035.View

J. D. Rocca et al., (2019). “The Microbiome Stress Project: Toward a Global Meta-Analysis of Environmental Stressors and Their Effects on Microbial Communities,” Front. Microbiol., vol. 9, doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.03272.View

R. Bachem, Y. Levin, X. Zhou, G. Zerach, and Z. Solomon, (2018). “The Role of Parental Posttraumatic Stress, Marital Adjustment, and Dyadic Self-Disclosure in Intergenerational Transmission of Trauma: A Family System Approach,” Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, vol. 44, no. 3, pp. 543–555, doi: 10.1111/jmft.12266.View

P. Checkland, Systems Thinking, Systems Practice: Includes a 30-Year Retrospective. Wiley, 1999.View

P. M. Senge, The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. Doubleday/Currency, 2006.View

P. Hanlon, S. Carlisle, M. Hannah, A. Lyon, and D. Reilly, (2012). “A perspective on the future public health: an integrative and ecological framework,” Perspect Public Health, vol. 132, no. 6, pp. 313–319, doi: 10.1177/1757913912440781.View

World Health Organization and M. Van Ommeren, Guidelines for the management of conditions specifically related to stress. 2013. Accessed: Sep. 02, 2020. [Online]. Available: http://www. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK159725/View

J. Sachs, “Global Happiness and Wellbeing Report, 2019.” New York: Sustainable Development Solutions Network, 2019.

C. M. Perez-Alvarado, E. Vargas-Madrazo, E. Montes-Villasenor, A. Valdez-Betanzos, G. E. Aranda, and M. E. Hernandez-Aguilar, (2018). “Integrative medicine review,” Int Res J Med Med Sci, vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 124–131, doi: 10.30918/ IRJMMS.64.18.062.View

M. Koithan, I. R. Bell, K. Niemeyer, and D. Pincus, (2012). “A Complex Systems Science Perspective for Whole Systems of Complementary and Alternative Medicine Research,” CMR, vol. 19, no. Suppl. 1, pp. 7–14, doi: 10.1159/000335181.View

S. Kuruvilla et al., (2018). “A life-course approach to health: synergy with sustainable development goals,” Bull World Health Organ, vol. 96, no. 1, pp. 42–50, doi: 10.2471/BLT.17.198358.View

I. R. Bell, M. Koithan, and D. Pincus, (2012). “Methodological Implications of Nonlinear Dynamical Systems Models for Whole Systems of Complementary and Alternative Medicine,” CMR, vol. 19, no. Suppl. 1, pp. 15–21, doi: 10.1159/000335183.View

M. T. Chao and S. R. Adler, (2018). “Integrative Medicine and the Imperative for Health Justice,” The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 101–103, doi: 10.1089/acm.2017.29042.mtc.View