Journal of Public Health Issues and Practices Volume 8 (2024), Article ID: JPHIP-230

https://doi.org/10.33790/jphip1100230Research Article

Job Tenure and Mental Health in the Mongolian Workplace

Ochirbat Batbold1,2, Christy Pu2*

1Medical School, Ach Medical University, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia.

2Department of Public Health, National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University, Taipei Taiwan.

*Corresponding Author Details: Christy Pu, PhD, Department of Public Health, National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University, Taipei Taiwan.

Received date: 08th November, 2024

Accepted date: 03rd December, 2024

Published date: 05th December, 2024

Citation: Batbold, O., and Pu, C., (2024). Job Tenure and Mental Health in the Mongolian Workplace. J Pub Health Issue Pract 8(2): 230.

Copyright: ©2024, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Background: Depression is a global mental health problem with major economic repercussions, affecting workplace productivity and individual well-being. In Mongolia, where the workforce is predominantly young and faces unique stressors, understanding the relationship between job tenure, depression, and occupational factors is essential. In this study, we evaluated the relationship between job tenure and depression in the Mongolian workplace.

Methods: Data were collected through a survey conducted among 1700 full-time employees in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, across 11 economic sectors. The study period was July to September 2018. Purposive sampling was used. Depression status was determined using Patient Health Questionnaire-9. Job tenure was defined as the duration (in months) for which an employee has been working for their respective company at the time of the survey. Statistical analyses included linear regression and chi-square tests, with a significance level set at P < 0.05.

Results: Compared with other individuals, blue-collar workers exhibited higher levels of depression, with 41% of female bluecollar workers experiencing moderate depression compared with 27% of male blue-collar workers. Overall, our results revealed a gender-specific difference. Compared with male workers, female workers experienced higher levels of depression throughout shorter job tenure (<150 months). However, this gender-specific difference diminished with increasing job tenure, indicating the potential role of job experience in mitigating gender-related differences in depression. Our result shows that longer job tenure is associated with lower depression scores.

Conclusion: Our results indicate the importance of addressing the mental health requirements of blue-collar workers and female employees in the Mongolian workforce. To mitigate mental health problems at the workplace, policies aimed at fostering a supportive work environment should account for job tenure among different workers.

Key words: Job tenure; Depression; Occupation

Introduction

Depression is a common mental health disorder that affects millions of people worldwide, and it has a major global burden [1]. According to estimates of the World Health Organization (WHO), depression and anxiety lead to the loss of approximately 12 billion working days worldwide every year, resulting in approximately US$1 trillion in lost productivity annually [2]. Depression has substantial economic repercussions, with implications for individuals, employers, and society as a whole [3].

Workplace depression is a major occupational health concern because it is associated with adverse outcomes such as functional disability and work impairment [3, 4]. Previous studies have reported mixed results regarding the prevalence rates of depression among different industries and occupational ranks [5-7].

Few studies have focused on workplace depression in Mongolia. Batbold and Pu [7] argued that compared with blue- and pink-collar workers, white-collar workers have a higher risk of depression. This elevated risk may be attributed to organizational injustice, defined as the perceived unfairness of workplace practices, and the heightened sensitivity of white-collar workers to changes such as business restrictions and downsizing. Increased sensitivity, characterized by greater emotional awareness and responsiveness, may make whitecollar workers more susceptible to workplace stressors and perceived instability. In contrast, blue- and pink-collar workers in Mongolia tend to benefit from greater job stability, which may contribute to lower levels of depression.

The objectives of this study were to investigate the relationship between job tenure and depression among different occupational groups and industries in Mongolia and to examine how gender may influence this relationship. We hypothesized that shorter job tenure would be associated with higher levels of depression, particularly among younger workers and women, due to their unique workplace challenges.

To the best of our knowledge, no study has yet examined the relationship between job tenure and depression across various occupation types. Changing jobs may affect mental health [8, 9]. Previous research has indicated that frequent mobility in the labor market increases the risk of common mental disorders. Other studies have indicated that job mobility may have a positive effect on job satisfaction and may reduce fatigue, particularly among self-employed individuals [10]. According to research, certain occupations are associated with an increased risk of psychological distress, and older and more experienced employees have higher levels of job satisfaction and lower levels of burnout than their younger counterparts. This level of distress may have a profound effect on productivity, workplace environment, physical health, employee satisfaction, and employee retention [11-13]. Some studies have indicated that financial satisfaction or strain is associated with mental well-being [14]. Nevertheless, these studies are limited to homogeneous groups working in a single field or organization [13-15].

Because workplace depression may be influenced by local culture, the results of studies conducted on Western or high-income countries may not be applicable to low- or middle-income countries. As a low- to middle-income country, Mongolia has distinct characteristics that lead to distinct workplace environments from that in higherincome Western countries. Mongolia also has distinct cultural norms, values, and organizational practices, which result in unique stressors and challenges. Both economic disparities and limited access to health-care services, which are common problems in Mongolia, may contribute to mental health problems [16, 17]. Therefore, these cultural and socioeconomic factors must be considered when examining workplace depression and designing tailored interventions [7, 13].

In this study, we investigated the relationship between job tenure and depression among different occupational groups and industries in Mongolia. Occupational rank was classified into three groups [18]: white collar (administrators, professionals, engineers, semiprofessionals, office workers, and business owners), pink collar (service workers, sales workers, and flight attendants), and blue collar (farmers, machine operators, assembly workers, and simple laborers) [19, 20]. This classification enabled a comparison of work characteristics between workers with privileges (e.g., white-collar workers) and those with low-wage, low-prestige jobs (e.g., blueand pink-collar workers). Certain challenges exist for the younger population in Mongolia. According to the Mongolian National Statistical Office, Mongolia has a relatively young population, with an average age of 26 years [21]. According to a study by the WHO, the workplace may provide opportunities and increase the risk of mental health disorders for workers, and certain workers, such as health, humanitarian, and emergency workers, are likely to be exposed to adverse experiences at work, with mental health problems being a major cause of death among younger individuals [2]. Compared with older workers with longer tenure, younger workers with shorter tenure are more likely to experience depression, and workplace violence and harassment are often enabled by structural factors such as gender bias, thus fostering a negative workplace culture [2]. In Mongolia, many young workers seek to emigrate to pursue educational and employment opportunities abroad [2]. This brain drain phenomenon may influence the composition of the local workforce and create unique stressors for industries that heavily rely on young talent. It may also affect job tenure for the workers remaining in Mongolia.

Another gap in the literature is the lack of research on the role of gender in the relationship between job tenure and depression. Compared with men, women are more likely to experience depression, and they are also more likely to have jobs that are associated with higher levels of stress [22]. In addition, women have shorter job tenure than men [23, 24]. This study addresses these gaps by exploring the interaction between job tenure, gender, and depression in Mongolia, considering cultural and workplace-specific factors.

Methods

Participants and sampling method

The study was conducted in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, from July to September 2018. A purposive sampling strategy was employed to ensure representation from diverse industries, including mining, manufacturing, electricity, construction, wholesale and retail, transportation, information and communication, insurance, public administration, education, and healthcare. Organizations were selected based on their market share and prominence within their respective sectors.

Invitations were sent to 35 organizations, of which 22 agreed to participate. Within these organizations, all employees were invited to participate in the survey. Employees were eligible for inclusion if they were full-time workers aged 18 or older and consented to participate. Participants who provided incomplete responses or had missing data for key variables were excluded from the analysis.

Response Rate and Final Sample

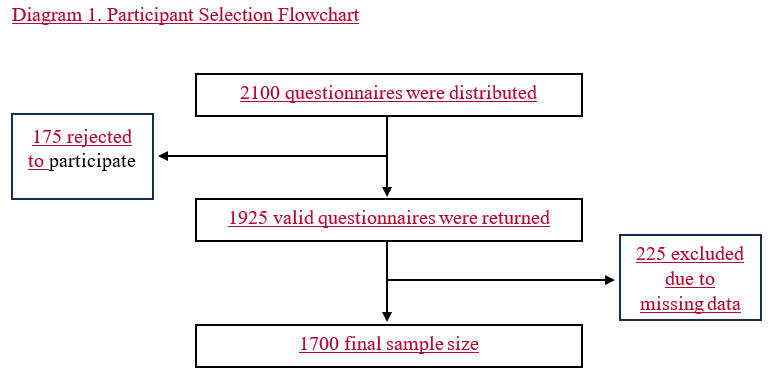

Of the 2,100 employees invited, 1,925 completed the survey, resulting in a response rate of 91.7%. After excluding 225 participants with incomplete or missing data, the final sample consisted of 1,700 respondents. The final sample included 49.8% blue-collar workers, 36.9% white-collar workers, and 13.3% pink-collar workers, providing balanced representation across occupational groups. (Figure 1.).

Depression Measure

Depression was evaluated using the Mongolian version of the (9- item) PHQ-9, a widely used self-report questionnaire for screening, diagnosing, monitoring, and measuring the severity of depression [7]. The PHQ-9 consists of nine simple questions, whose answers are scored on a scale with endpoints ranging from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating a larger number of symptoms of psychiatric disturbance [25, 26]. The total score for major depressive disorders or other depressive disorders ranges from 0 to 27.

Tenure Measure

Job tenure was evaluated and measured using a combination of self-report measures and based on employment records. Each participant was asked to report their length of service by months (job tenure) in their current occupation and organization. The data were subsequently cross-referenced with employment records obtained from participating organizations or companies to validate and verify the reported job tenure. The tenure categories—<12 months, 12–60 months, 61–120 months, and >121 months—were selected to reflect different stages of employment, which may have varying effects on mental health outcomes. Using this comprehensive approach, we obtained an accurate and reliable assessment of job tenure for our sample, thus enabling a robust analysis of the relationship between tenure and mental health outcomes across various occupational groups and industries in Mongolia.

Other Variables

In addition to occupational rank, several other variables were included as predictors of depression. For example, age and self-rated health (Generally, would you say your health is very good, good, fair, poor, or bad?) were included as measures of general health status. In addition, educational level (primary, secondary, college, university, or postgraduate), gender (male or female), and marital status (single, married, cohabitating, divorced, or widowed) were included as variables. These variables were selected using a modelbuilding process.

Statistical Analysis

To ensure that our sample, which was aimed at representing the working population of Ulaanbaatar, was adjusted for imbalances between probability and nonprobability samples, we used a modelbased weighting technique proposed by Valliant [27]. This technique involves using a set of covariates to adjust for differences between the sample and nonsample, with the availability of population totals being required. We obtained the population totals for different age brackets and sex proportions for each industry from the national labor statistics from the National Labor Department. Following the instructions of Valliant [27], we assumed a linear model for the analysis variable y and used Taylor’s linearization to calculate standard errors. Because our sample represented only a small fraction of the entire population, the prediction estimator was the approximate summation of the predictions for each unit in the population [27].

After the PHQ-9 was modeled as a continuous variable and a linear regression accounting for survey weight was applied, a modelbuilding strategy was used, which included an exploratory bivariate analysis to determine the relevant variables. These variables were required to be scientifically relevant to the outcome variable (PHQ-9) and to have a statistical significance of P < 0.25 based on bivariate analysis. To make the model parsimonious, Wald’s tests for multiple coefficients were conducted to remove redundant variables. However, we retained the variable of educational level, despite its nonsignificance, because of its strong scientific relevance. We also included an interaction term between gender and job tenure to determine whether the effect of job tenure on depression is influenced by gender. The final model was selected according to the Akaike information criterion [28].

Results

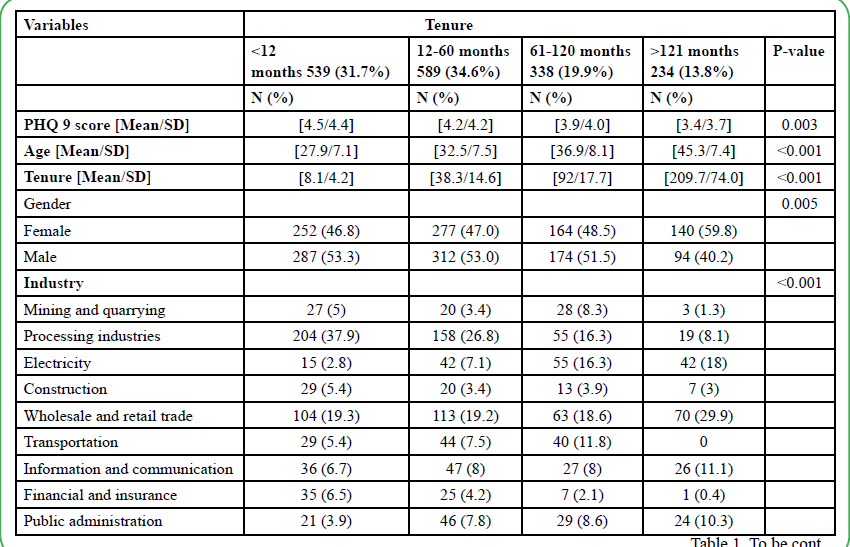

Table 1. lists the sociodemographic characteristics of the study sample by job tenure. We classified the participants into four groups, namely <12 months of job tenure (31.7%), 12–60 months of job tenure (34.6%), 61–120 months of job tenure (19.9%), and >121 months of job tenure (13.8%), with 51% of the sample being men. The mean PHQ-9 score was 4.1 (standard deviation [SD] = 4.2), and the mean job tenure was 63.0 (SD = 72.1) months. In terms of the educational level, more than 50% of workers in the first three groups had university-level education. For workers with >121 months of job tenure, 33.8% had university-level education, and 20.5% had postgraduate-level education. For workers with <12 months, 12–60 months, and 61–120 months of job tenure, 5.8%, 11.0%, and 12.4%, respectively, had postgraduate-level education. For workers with <12 months of job tenure, 14.5% reported having financial difficulties (reported “not enough” for the financial status question), whereas among workers with >121 months of job tenure, only 2.6% reported having financial difficulties. Occupational groups were divided by collar. Workers with <12 months of job tenure comprised a large proportion of blue-collar workers (54.4%), whereas workers with >121 months of job tenure comprised a large proportion of pink-collar workers (18.8%). In terms of marital status, 65.4% of the participants were married, 25.7% were single, and the remaining were divorced, widowed, or cohabitating.

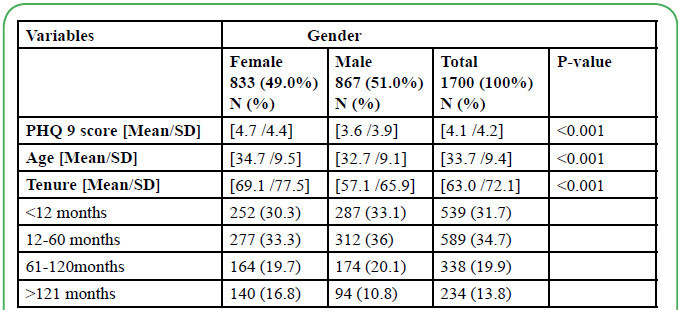

Table 2. presents the distribution of sociodemographic variables stratified by gender. The average age of the participants was 33.7 years, with women being slightly older (34.7 years, SD = 9.5) than men (32.7 years, SD = 9.1). Compared with the average PHQ-9 score of men (3.6, SD = 3.9), women had a higher score (4.7, SD = 4.4). On average, women had longer job tenure (69.1 months, SD = 77.5) than men (57.1 months, SD = 65.9). Female workers with >120 months of job tenure comprised 16.8% of the sample, whereas male workers with >120 months of job tenure comprised only 10.8% of the sample.

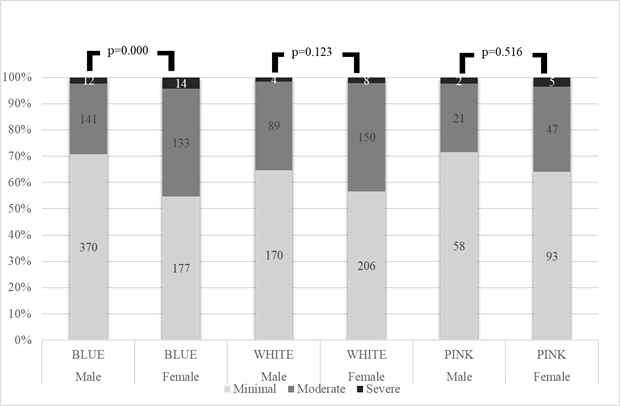

Figure 2. provides the prevalence of depression by gender among different occupational groups. Among all occupational groups, female workers exhibited higher levels of moderate and severe depression than their male counterparts. In the blue-collar occupational group, 41% of female workers experienced moderate depression compared with only 27% of male workers. In the white-collar occupational group, 41% of female workers experienced moderate depression compared with only 34% of male workers. In the pink-collar occupational group, 32% of female workers experienced moderate depression compared with only 26% of male workers.

Figure 2: Prevalence of depression levels stratified by gender among different occupational groups (collars).

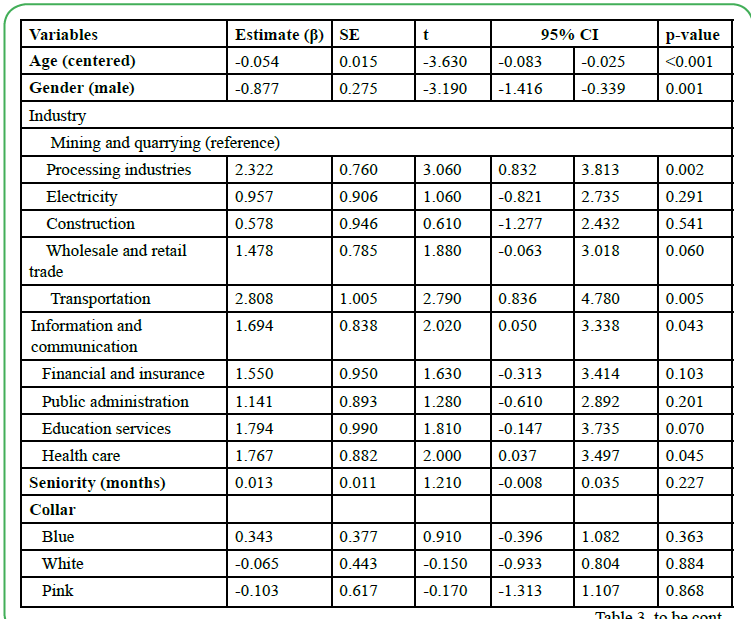

Table 3. presents a full model of interactions based on the aforementioned model-building process. Age was negatively correlated with a lower PHQ-9 score (β = −0.054, P < 0.001). In terms of industry, processing, wholesale and retail, transportation, information and communication, and health care were associated with a higher average PHQ-9 score than mining. Married individuals had a lower PHQ-9 score than single individuals (β = −1.063, P < 0.001). Although job tenure itself was not significantly associated with depression, it exhibited a certain interaction with the three groups of occupational rank (collar). Specifically, the PHQ-9 score of blue-collar workers decreased with job tenure, but this effect was nonsignificant for both white- and pink-collar workers. No significant interaction was observed between job tenure and industry.

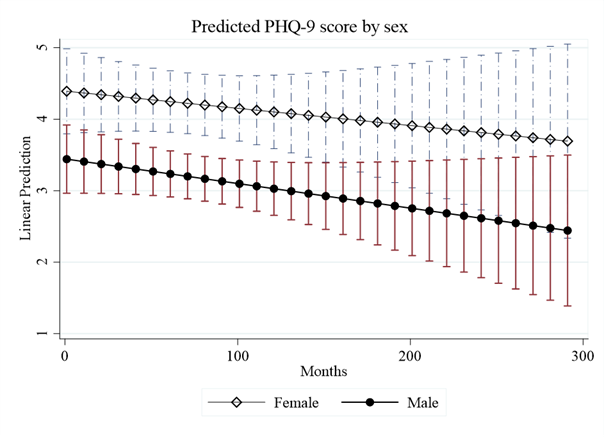

To facilitate the interpretation of job tenure and its interaction with gender, we calculated the marginal effects of tenure over 10-month intervals. Figure 3. shows the effect of job tenure on depression scores stratified by gender. Compared with men, women had higher predicted PHQ-9 scores, and the differences between their predicted scores stratified by gender were more prominent with shorter job tenure. For both male and female workers, the predicted marginal effects revealed a slight decline in their depression scores as their job tenure increased.

Discussion

In the current study, we examined the relationship between depression, job tenure, and occupational characteristics among the working population of Mongolia. The following are the key findings of this study. First, depression levels decrease as job tenure increases among blue-collar workers, but not among white- or pinkcollar workers. Second, depression scores differ by industry, but no significant interaction exists between industry and job tenure. Third, compared with men, women experience higher levels of depression with shorter job tenure, but no gender-specific difference exists for longer job tenure.

Although previous studies have investigated the relationship between different industries or occupations and the risk of depression, these studies have certain limitations [29]. Specifically, none of these studies has examined the relationship between job tenure and depression or has focused on the differences between collars and industries. Thus, data on occupation-related depression are currently lacking, especially in developing countries such as Mongolia [7].

This study underscores the need for occupational justice by highlighting mental health disparities linked to job tenure, gender, and occupational roles. To address these disparities, we propose actionable policy recommendations aimed at improving working conditions, such as promoting workplace mental health support and offering career development opportunities, particularly for blue-collar workers and early-career women. Addressing these inequalities requires targeted support for disadvantaged groups, such as blue-collar workers and early-career women, through inclusive policies that promote equitable access to mental health resources and supportive work environments. Moreover, strengthening links between the findings and occupational justice can guide the implementation of policies aimed at reducing occupational disparities and fostering mental well-being across various sectors.

In this study, we discovered that among the Mongolian working population, the risk of depression is high among blue-collar workers; however, the levels of depression decrease with increasing job tenure This may be explained by the unique challenges faced by blue-collar workers in Mongolia. Unlike white-collar workers, blue-collar workers often experience physically demanding work conditions, lower income, and limited access to resources such as workplace mental health support or career advancement opportunities. These factors may contribute to increased stress, financial insecurity, and a lack of professional fulfillment, all of which are linked to higher rates of depression. This research outcome is consistent with previous research indicating higher depression scores among blue-collar workers than among white-collar workers [6, 7, 13]. Overall, our findings have major implications for policymakers, highlighting the necessity of tailored interventions and support structures for bluecollar workers in Mongolia, who may be susceptible to depression development because of their long working hours and few promotion opportunities [20]. To promote mental well-being among this vulnerable workforce segment, labor conditions must be improved [30], and job-related stressors inherent to blue-collar sectors must be mitigated [6].

Overall, the variations observed in depression scores across different industries suggest the presence of unique stressors and challenges inherent to specific occupational sectors in Mongolia. Certain industries such as transportation and processing have high work demands, increased job strain, or other factors that may contribute to elevated levels of depression among workers [7]. Both the repetitive nature of tasks and the subjective monotony of work are regarded as key stressors [31]. Understanding these industry-specific differences is crucial for developing targeted interventions and support systems aimed at addressing the mental health requirements of workers in vulnerable sectors. However, these findings are specific to the context of Mongolia and may not be directly applicable to other countries with different economic and labor conditions. The generalizability of these findings to populations outside of Mongolia should be considered with caution. Future studies should focus on the unique challenges, such as remote work, aging, and health-care disparities, faced by different occupational groups and industries and should explore effective interventions aimed at improving the psychosocial environment at the workplace [32].

Compared with male workers, female workers experience higher levels of depression during the early stage of their job tenure. However, as job tenure increases, the difference observed in the levels of depression between men and women diminishes, indicating that job tenure plays a role in mitigating gender-specific differences in the levels of depression. These gender-specific differences associated with short job tenure indicate the need for targeted support systems and interventions aimed at addressing the mental health requirements of female workers, especially during the early stage of their careers [33]. Overall, our findings can be explained as follows. First, many women face additional caregiving responsibilities [34], which may occur at a younger age, thus explaining the higher levels of depression among women with shorter job tenure, which is likely also associated with younger age. Second, as job tenure increases, female workers tend to gain more experience, which may decrease the work disadvantages that they may face. Previous studies have indicated that increased work experience is positively associated with job satisfaction [35, 36]. This finding highlights the need for interventions tailored for women during the early stage of their careers, helping them adjust to their work conditions in the long term.

This study has some limitations. First, the data were obtained using a self-report survey, which may have resulted in response bias. In addition, because this study had a cross-sectional design, we were able to examine only the relationship between depression and occupational status and could not examine causal relationships. Second, the generalizability of the findings is limited to the working population of Mongolia and may not be applicable to other regions with different socioeconomic or cultural contexts. Third, we were unable to identify the mechanisms underlying the relationship between job tenure and depression. Future studies should focus on understanding the unique challenges, such as remote work, aging, and health-care disparities, faced by different occupational groups and industries and exploring effective interventions aimed at improving the psychosocial environment at the workplace [32]. We acknowledge that selection bias may have influenced our findings. While purposive sampling ensured diverse representation across sectors, certain groups, such as employees with severe depression or heavy workloads, may have been underrepresented. Although we invited all employees from selected organizations, future studies should adopt probabilty sampling methods to reduce potential bias. In addition, there may be misclassification of depression; this study employed the PHQ-9, a validated self-report tool, to assess depression. However, self-reported data can be subject to biases such as underreporting due to social desirability. Additionally, the PHQ-9 may not capture all dimensions of depression.

Conclusion

In the framework of this study, we examined the relationship between job tenure and depression among the working population of Mongolia. Our results provided valuable insights into the complex relationship between depression scores, job tenure, and occupational factors. Specifically, we discovered that depression scores differ by industry, indicating the presence of industry-specific stressors, but the effect of job tenure on depression remains constant across different sectors. We also observed a gender-specific difference in depression, with higher levels of depression among women with short job tenure than among men. However, this gender-specific difference diminishes with increasing job tenure, indicating the potential role of job experience in mitigating gender-related differences in depression.

Notably, our results revealed an increased risk of depression among blue-collar workers, which may be attributable to their physically demanding work, economic stress, and limited access to mental health resources. Cultural factors, including the stigma surrounding mental health, could exacerbate these issues, further complicating efforts to improve mental health outcomes in the workplace. Therefore, addressing the mental health requirements of this vulnerable worker population through targeted interventions is essential to improve their mental well-being in the workplace.

Based on the aforementioned findings, both policymakers and employers should implement inclusive workplace policies that support both blue-collar workers and female employees during the early stage of their job tenure. Creating a more supportive work environment, offering targeted mental health resources, and considering organizational factors such as job tenure may mitigate depression disparities and yield improved mental health outcomes for all employees in Mongolia.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical approval:

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of National Yang-Ming University, Taipei, Taiwan (YM107064E-2) and the Medical Ethics Committee of Ach Medical University, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia (12/23).

Funding:

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Author contributions:

OB collected the data. CP analyzed the data. Both authors wrote the manuscript and approved the manuscript together.

References

World Health Organization (2017). Depression and other common mental disorders: global health estimates, World Health Organization.View

World Health Organization. (2022). "Mental health at work." View

Shin, Y. C., D. Lee, J. Seol and S. W. Lim (2017). "What Kind of Stress Is Associated with Depression, Anxiety and Suicidal Ideation in Korean Employees?" J Korean Med Sci 32(5): 843- 849.

Reddy, M. S. (2010). "Depression: the disorder and the burden." Indian journal of psychological medicine. 32(1): 1-2. View

Nakamura-Taira, N., S. Izawa and K. C. Yamada (2018). "Stress underestimation and mental health literacy of depression in Japanese workers: A cross-sectional study." Psychiatry Res. 262: 221-228. View

Elser, H., D. H. Rehkopf, V. Meausoone, N. P. Jewell, E. A. Eisen and M. R. Cullen (2019). "Gender, depression, and bluecollar work: A retrospective cohort study of US aluminum manufacturers." Epidemiology, 30(3): 435-444. View

Batbold, O. and C. Pu (2021). "Disparities in Depression Status Among Different Industries in Transition Economy: A Cross-Sectional Study of Mongolia." Asia Pac J Public Health: 10105395211001171. View

De Raeve, L., I. Kant, N. W. H. Jansen, R. M. Vasse and P. A. van den Brandt (2009). "Changes in mental health as a predictor of changes in working time arrangements and occupational mobility: Results from a prospective cohort study." Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 66(2): 137-145. View

Aydıntan, B. and H. Koç (2016). "The Relationship between Job Satisfaction and Life Satisfaction: An Empirical Study on Teachers." 7. View

Hougaard, C. Ø., E. Nygaard, A. L. Holm, K. Thielen and F. Diderichsen (2016). "Job mobility and health in the Danish workforce." Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 45(1): 57- 63. View

Liljegren, M. and K. Ekberg (2008). "The longitudinal relationship between job mobility, perceived organizational justice, and health." BMC public health 8: 164. View

Liljegren, M. and K. Ekberg (2009). "Job mobility as predictor of health and burnout." Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 82(2): 317-329. View

Laditka, J. N., S. B. Laditka, A. A. Arif and O. J. Adeyemi (2023). "Psychological distress is more common in some occupations and increases with job tenure: a thirty-seven year panel study in the United States." BMC psychology, 11(1): 1-11. View

Hassan, M.F., Kassim,N. M., & Said,Y.M.U., (2021).Financial Wellbeing and Mental Health: A Systematic Review. Studies of Applied Economics, 39(4). View

Wulsin, L., T. Alterman, P. Timothy Bushnell, J. Li and R. Shen (2014). "Prevalence rates for depression by industry: a claims database analysis." Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology, 49(11): 1805-1821. View

Knapp, M., M. Funk, C. Curran, M. Prince, M. Grigg and D. McDaid (2006). "Economic barriers to better mental health practice and policy." Health policy and planning, 21(3): 157- 170. View

Lhamsuren, K., T. Choijiljav, E. Budbazar, S. Vanchinkhuu, D. C. Blanc and J. Grundy (2012). "Taking action on the social determinants of health: improving health access for the urban poor in Mongolia." International Journal for Equity in Health,11(1): 15. View

Segal, L. M., & Sullivan, D. G., (1997).The Growth of Temporary Services Work. Journal of Economic Perspectives.11(2). View

Lips-Wiersma, M., Wright, S., & Dik, B. (2016). Meaningful work: Differences among blue-, pink-, and white-collar occupations. The Career Development International, 21(5), 534–551. View

Yoon, Y., J. Ryu, H. Kim, C. W. Kang and K. Jung-Choi (2018). "Working hours and depressive symptoms: the role of job stress factors." Annals of occupational and environmental medicine,30: 46-46. View

National Statistics Office of Mongolia. (2018). "Mongolian Statistical Information Service." Retrieved 12 Jan, 2020. View

World Health Organization (2022). "World mental health report: transforming mental health for all." View

Kang, H.-R. and C. Rowley (2013). Women in management in South Korea: advancement or retrenchment? Women in Asian Management, Routledge: 73-91. View

Cook, A. and C. Glass (2014). "Women and top leadership positions: Towards an institutional analysis." Gender, Work & Organization, 21(1): 91-103. View

Kohrt, B. A., N. P. Luitel, P. Acharya and M. J. D. Jordans (2016). "Detection of depression in low resource settings: validation of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and cultural concepts of distress in Nepal." BMC psychiatry, 16: 58-58. View

Manea, L., J. R. Boehnke, S. Gilbody, A. S. Moriarty and D. McMillan (2017). "Are there researcher allegiance effects in diagnostic validation studies of the PHQ-9? A systematic review and meta-analysis." BMJ open, 7(9): e015247-e015247. View

Valliant, R. and J. A. Dever (2018). Survey weights: a step-bystep guide to calculation, Stata Press College Station, TX.

Cavanaugh, J. E. and A. A. Neath (2019). "The Akaike information criterion: Background, derivation, properties, application, interpretation, and refinements." Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Statistics, 11(3): e1460. View

Battams, S., A. M. Roche, J. A. Fischer, N. K. Lee, J. Cameron and V. Kostadinov (2014). "Workplace risk factors for anxiety and depression in male-dominated industries: a systematic review." Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine: an Open Access Journal, 2(1): 983-1008. View

Liu, L., L. Wang and J. Chen (2014). "Prevalence and associated factors of depressive symptoms among Chinese underground coal miners." BioMed research international 2014. View

Melamed, S., I. Ben-Avi, J. Luz and M. S. Green (1995). "Objective and subjective work monotony: effects on job satisfaction, psychological distress, and absenteeism in bluecollar workers." Journal of Applied Psychology, 80(1): 29. View

Rudolph, C. W., B. Allan, M. Clark, G. Hertel, A. Hirschi, F. Kunze, K. Shockley, M. Shoss, S. Sonnentag and H. Zacher (2021). "Pandemics: Implications for research and practice in industrial and organizational psychology." Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 14(1-2): 1-35. View

Petrongolo, B. and M. Ronchi (2020). "Gender gaps and the structure of local labor markets." Labour Economics, 64: 101819. View

Revenson, T. A., K. Griva, A. Luszczynska, V. Morrison, E. Panagopoulou, N. Vilchinsky, M. Hagedoorn, T. A. Revenson, K. Griva and A. Luszczynska (2016). "Gender and caregiving: The costs of caregiving for women." Caregiving in the illness context: 48-63. View

Kavanaugh, J., J. A. Duffy and J. Lilly (2006). "The relationship between job satisfaction and demographic variables for healthcare professionals." Management Research News, 29(6): 304-325. View

Peiró, J. M., S. Agut and R. Grau (2010). "The relationship between overeducation and job satisfaction among young Spanish workers: The role of salary, contract of employment, and work experience." Journal of applied social psychology, 40(3): 666-689. View