Journal of Public Health Issues and Practices Volume 9 (2025), Article ID: JPHIP-245

https://doi.org/10.33790/jphip1100245Mini Review

Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Health Workforce Development: Key Insights and Considerations

Tokesha L. Warner1*, Miranda Sanford Terry2, & Brian Calhoun?3

1* Assistant Professor, Department of Public Health, Health Administration & Information and Health Sciences, Tennessee State University, United States.

2 Professor, Department of Public Health, Health Administration & Information and Health Sciences, Tennessee State University,United States.

3 Doctoral Public Health Student, Department of Public Health, Health Administration & Information and Health Sciences, Tennessee State University, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Tokesha L. Warner, Assistant Professor, Department of Public Health, Health Administration & Information and Health Sciences, Tennessee State University, United States.

Received date: 22nd August, 2025

Accepted date: 29th September, 2025

Published date: 03rd October, 2025

Citation: Warner, T. L., Terry, M. S., & Calhoun, B., (2025). Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Health Workforce Development: Key Insights and Considerations. J Pub Health Issue Pract 9(2): 245.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

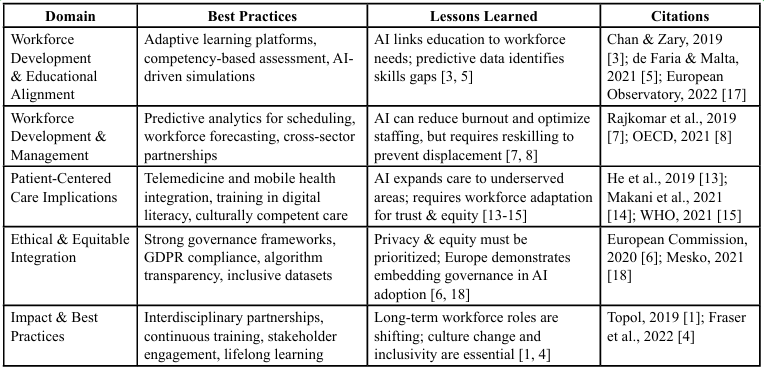

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is reshaping healthcare by enhancing efficiency, improving outcomes, and supporting cost reduction. This manuscript examines how AI integration is transforming workforce development in health professions, particularly in recruitment, training, competency assessment, and workforce management. The analysis synthesizes global perspectives to identify best practices and ethical considerations. We organize findings into five domains: (1) workforce development and educational alignment, (2) workforce development and management, (3) patient-centered care implications, (4) ethical and equitable integration, and (5) impacts and best practices. By situating AI within the broader framework of workforce development, this review highlights opportunities for strengthening healthcare training and delivery while ensuring equity, accountability, and sustainability.

Keywords: Artificial Intelligence (AI), Workforce Development, Public Health, Health Services, Health Education, Global Health, Equity

Introduction

The adoption of Artificial Intelligence (AI) is accelerating across healthcare systems worldwide, reshaping clinical care, administration, and education. In the health workforce context, AI introduces tools for adaptive training, predictive workforce planning, and enhanced patient-centered care. While enthusiasm for AI adoption is high, integration requires thoughtful attention to equity, ethics, and global lessons learned [1,2].

This paper reviews current and emerging uses of AI in health workforce development with an emphasis on educational alignment, workforce management, patient-centered implications, and equity. The structure incorporates global case studies, synthesizes cross sector lessons, and proposes best practices to guide policymakers, educators, and healthcare leaders.

Workforce Development and Educational Alignment

U.S., Canada, and Latin America

AI technologies have transformed health education by enabling adaptive learning, competency-based assessment, and scalable simulations. In the U.S., AI-driven virtual patients and simulation labs support medical and nursing education by replicating complex scenarios while tailoring feedback to learner needs [3]. Canada has similarly integrated AI in competency-based frameworks, using predictive analytics to identify student performance gaps [4]. In Latin America, AI has been deployed to improve access to high-quality training in resource-constrained settings, where adaptive learning platforms address faculty shortages and uneven training capacity [5].

AI’s role in aligning education with workforce needs extends beyond classrooms. Predictive analytics link population health data with training priorities, ensuring curricula adapt to emerging health challenges. For example, AI systems analyzing epidemiological data can inform nursing school recruitment strategies in areas with projected shortages [6].

Workforce Development and Management

AI also enables healthcare organizations to address operational workforce challenges. In the U.S. and Canada, predictive scheduling algorithms improve staff allocation, reduce burnout, and anticipate patient surges [7]. Workforce planning tools use AI to forecast shortages of specialized clinicians, guiding investment in graduate medical education.

Globally, management applications include Brazil’s use of AI- enabled dashboards to redistribute health workers across regions, and Canada’s reliance on machine learning models to simulate retirement patterns in nursing [8]. These innovations underscore that effective AI integration requires cross-sector partnerships and reskilling programs to ensure healthcare workers can adapt to evolving roles.

Artificial intelligence is becoming deeply integrated into essential public health operations, enhancing syndromic surveillance and outbreak analysis by combining conventional reporting methods with digital data streams to improve detection speed and sensitivity [9]. Public health teams leverage machine learning for risk categorization, incorporating social determinants of health to pinpoint high-needs areas and populations for targeted interventions while actively addressing fairness and mitigating bias to ensure equitable model outcomes [10]. Natural language processing tools bolster event-based monitoring by deriving actionable insights from unstructured text—like clinician notes, customer service logs, and media reports—greatly extending situational awareness beyond what is possible through manual review [9]. AI-driven solutions further assist in developing and testing culturally appropriate health messages, as well as tracking misinformation trends, aligning with governance frameworks adopted in AI-focused health projects to uphold transparency, reproducibility, and ethical application [10]. Additionally, public health organizations invest in building expertise around data science and ethical AI by incorporating measures such as equity audits, thorough documentation of models, and continuous oversight following deployment to maintain credibility and responsible use in population health interventions [10,11].

Grant-funded initiatives leveraging AI in workforce development and educational alignment are establishing structured pathways for upskilling, including stackable micro-credentials, hands-on practice and mentored residencies. These efforts aim to enhance competencies in areas such as data stewardship, model interpretation, and ethical AI practices for public health and clinical staff [12]. Increasingly, grant programs mandate the inclusion of curricula incorporating critical skills like fairness auditing, subgroup performance analysis, and bias mitigation strategies, aligning higher education offerings (e.g., MPH, MS, Health Informatics) with practical deployment demands through co-created syllabi and capstone collaborations with health departments [12]. Multi-disciplinary training teams connect data scientists with epidemiologists, nurses, and community health workers to foster shared mental models for ethical AI use, complemented by governance labs that emphasize documentation, transparency reporting, and post-deployment monitoring [12]. Grant- supported workforce pipelines prioritize investments in interoperable data systems and subject matter expertise—spanning data quality control, model versioning, and drift detection—to empower trainees in maintaining and advancing AI tools well beyond a project's lifecycle [12]. Moreover, these grants embed structured career progression frameworks within partner organizations, connecting demonstrated skills in equity-centered AI to advancement and retention mechanisms, with the goal of sustaining organizational capacity after pilot programs are concluded [12].

Patient-Centered Care Implications

China, Japan, and African Countries

In patient care, AI adoption intersects directly with workforce development by altering provider roles. In China and Japan, AI tools support diagnostic accuracy and chronic disease management, offsetting workforce shortages among aging populations [13]. African nations are pioneering AI-enabled telemedicine to extend services to remote and rural areas, simultaneously requiring new competencies for health workers in digital literacy and virtual care [14].

For the U.S., lessons from global rural telemedicine are particularly relevant. AI-powered mobile health solutions can bridge provider shortages in underserved American communities, but require workforce training in culturally competent digital care delivery [15]. Thus, patient-centered AI applications necessitate reimagining provider roles, emphasizing adaptability, and fostering trust with populations historically excluded from technological advances.

To address healthcare gaps amid diverse infrastructure scenarios, African health systems could integrate AI-backed telemedicine and triage tools for prioritizing urgent cases and minimizing travel challenges. Predictive analytics further strengthen health programs focusing on HIV, TB, and non-communicable disease follow-ups. Approaches tailored for connectivity constraints—such as offline first mechanisms with low-bandwidth reliance like SMS or USSD— combined with culturally and linguistically relevant interfaces improve accessibility and usability of solutions [16].

Ethical and Equitable Integration

European Approaches

European countries emphasize governance frameworks to ensure ethical, equitable AI use in healthcare. The U.K. and Germany prioritize robust data privacy protections and algorithmic transparency [17]. France has developed national AI strategies that embed equity into workforce policies, requiring datasets to include diverse populations to reduce bias [18].

Two critical subsections define this domain:

• Data Privacy: Protecting sensitive patient and workforce data is foundational to AI trust. The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) provides an example of balancing innovation with patient rights.

• Equity: Addressing algorithmic bias and ensuring equitable distribution of AI benefits remains essential. Without deliberate inclusion, AI risks reinforcing structural inequities in health systems.

By embedding equity and privacy safeguards, European experiences illustrate how governance can inform global best practices for AI adoption in health workforce development.

Impact and Best Practices

Global Lessons

The impact of AI on health workforce development is transformative. Roles are shifting from routine administrative functions to higher- order tasks requiring empathy, critical thinking, and collaboration with AI systems [1]. The long-term implications include:

• Creation of new professions (e.g., digital health coordinators, AI ethicists).

• Increased demand for data science skills in health education.

• Workforce displacement risks requiring reskilling and lifelong learning programs.

Best practices identified across contexts include:

1. Interdisciplinary Partnerships: Collaboration between technology developers, educators, and health systems enhances AI relevance.

2. Continuous Faculty Training: Upskilling educators ensures AI tools are effectively integrated into curricula.

3. Policy and Governance: Strong guidelines mitigate risks of bias and privacy breaches.

4. Stakeholder Engagement: Inclusion of patients, providers, and policymakers fosters legitimacy and adoption.

Importantly, global case studies reveal that successful integration requires not only technical deployment but also organizational culture change and investments in equity.

Conclusion

AI integration in health workforce development holds transformative potential but must be guided by equity, ethics, and global learning. From adaptive education in North America and Latin America, to patient-centered telemedicine in Africa, to privacy-focused frameworks in Europe, diverse experiences highlight pathways forward. The lessons point to a common imperative: AI must strengthen, not replace, the human-centered mission of healthcare.

By embedding best practices, fostering cross-sector collaboration, and prioritizing equity, the health workforce can harness AI’s capabilities to deliver more effective, inclusive, and sustainable care worldwide.

Competing Interests:

The author declares that they have no competing interests.

List of Abbreviations

AI: Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to acknowledge Dr. Robbie Melton, Provost and Vice President of Academic Affairs, and Vice President for SMART AI/ IOE Applied Technology Innovations Center at Tennessee State University and her amazing team in the SMART Center.

References

Topol, E. (2019). Deep medicine: How artificial intelligence can make healthcare human again. Basic Books. View

Davenport, T., & Kalakota, R. (2019). The potential for artificial intelligence in healthcare. Future Healthcare Journal, 6(2), 94 98. View

Chan, K. S., & Zary, N. (2019). Applications and challenges of implementing artificial intelligence in medical education: Integrative review. JMIR Medical Education, 5(1), e13930. View

Fraser, N., Brierley, L., Dey, G., Polka, J. K., Pálfy, M., Nanni, F., & Coates, J. A. (2022). The evolving role of AI in Canadian health professions education. Canadian Medical Education Journal, 13(3), e1–e6.

de Faria, A. R., & Malta, D. C. (2021). Artificial intelligence in public health training in Latin America: Opportunities and challenges. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública, 45, e112.

European Commission. (2020). White paper on artificial intelligence: A European approach to excellence and trust. Publications Office of the European Union. View

Rajkomar, A., Dean, J., Kohane, I., (2019). Machine Learning in Medicine. N Engl J Med. 380(14):1347-1358. View

OECD. (2021). Artificial intelligence in society. OECD Publishing. View

Santillana, M., Nguyen, A. T., Dredze, M., Paul, M. J., Nsoesie, E. O., & Brownstein, J. S. (2015). Combining Search, Social Media, and Traditional Data Sources to Improve Influenza Surveillance. PLOS Computational Biology, 11(10), e1004513. View

Zou, J., & Schiebinger, L. (2018). AI can be sexist and racist — it’s time to make it fair. Nature, 559(7714), 324–326. View

Beam, A. L., & Kohane, I. S. (2018). Big Data and Machine Learning in Health Care. JAMA, 319(13), 1317. View

Obermeyer, Z., Powers, B., Vogeli, C., & Mullainathan, S. (2019). Dissecting Racial Bias in an Algorithm Used to Manage the Health of Populations. Science, 366(6464), 447–453. View

He, J., Baxter, S. L., Xu, J., Xu, J., Zhou, X., & Zhang, K. (2019). The practical implementation of artificial intelligence technologies in medicine. Nature Medicine, 25, 30–36. View

Makani, J., Oladipo, Y., & Mensah, S. (2021). Artificial intelligence in African health systems: Expanding access through telemedicine. BMJ Global Health, 6(7), e006765.

World Health Organization. (2021). Global strategy on digital health 2020–2025. WHO." View

He, J., Baxter, S. L., Xu, J., Xu, J., Zhou, X., & Zhang, K. (2019). The practical implementation of artificial intelligence technologies in medicine. Nature Medicine, 25(1), 30–36. View

European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2022). Health workforce planning and forecasting. WHO Regional Office for Europe. View

Mesko, B. (2021). The role of artificial intelligence in precision medicine and equitable healthcare. NPJ Digital Medicine, 4(1), 132. View