Journal of Public Health Issues and Practices Volume 9 (2025), Article ID: JPHIP-247

https://doi.org/10.33790/jphip1100247Research Article

Comparing Online Synchronous and In-Person Motivational Interviewing Instruction: Learning Outcomes, Preferences, and Satisfaction Among Public Health Professionals

Mary Larson1*, and Shannon David2

1Associate Professor, Department of Public Health, North Dakota State University (NDSU), NDSU Dept. 2662, PO Box 6050, Fargo, ND 58108-6050, United States.

2Professor, Department of Health, Nutrition, and Exercise Science, North Dakota State University, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Mary Larson, Associate Professor, Department of Public Health, North Dakota State University (NDSU), NDSU Dept. 2662, PO Box 6050, Fargo, ND 58108-6050, United States.

Received date: 25th September, 2025

Accepted date: 27th November, 2025

Published date: 29th November, 2025

Citation: Larson, M., & David, S., (2025). Comparing Online Synchronous and In-Person Motivational Interviewing Instruction: Learning Outcomes, Preferences, and Satisfaction Among Public Health Professionals. J Pub Health Issue Pract 9(2): 247.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Motivational interviewing (MI) is an evidence based communication method used by public health professionals to promote health behavior change. Traditionally, MI instructors used in person pedagogical methods for training learners, but geographical disparities necessitated the development of distance learning, and the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic further motivated a shift to online, virtual pedagogical methods. This study evaluated the feasibility and acceptability of online synchronous versus in person pedagogical methods for MI instruction among public health professionals.

Forty professionals were randomly assigned to an online synchronous or in-person MI training group. Both groups received 14 hours of training from the same instructor using an identical curriculum. A mixed-method evaluation approach was used to measure the learning and acceptability of the training. Attrition following randomization led to participant dropout. Participants (n=16) submitted a recorded MI session for evaluation by trained MI coders using the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity 4.2.1 (MITI 4.2.1) instrument were included in the analysis to determine MI skill and spirit competence. Pre- and post-training surveys were used to evaluate training preferences and satisfaction.

MITI 4.2.1 global rating scores did not differ significantly between the two training modalities. The only behavioral count that differed was "giving information," which was statistically higher in the online group. Overall satisfaction was significantly greater among the in-person training group. Participants also expressed a stronger preference for in-person MI training. Several participants dropped out of the study, especially among the participants assigned to the online group, which impacted the robustness of the results.

Maintaining fidelity is crucial when delivering evidence-based training. While online synchronous and in-person MI training pedagogy produced similar MITI 4.2.1 outcomes, participants were more satisfied with and preferred the in-person pedagogical approach. These findings support the feasibility of using synchronous online MI training methods to produce acceptable training outcomes for geographically remote participants.

Keywords: Online Synchronous Pedagogy, In-Person Pedagogy, Randomization, Mixed Method Evaluation, Motivational Interviewing Training, Preference Assessment

Introduction

Motivational Interviewing (MI) is an evidence-based conversational approach where a practitioner embodies a way of being that increases a person's intrinsic motivation for change. It is used in a variety of settings, such as primary care, public health, social services, etc., with patients or clients to promote positive behavior change (e.g., tobacco cessation, dietary improvement) [1-5].

MI is taught through participation in workshops, supervised practice, coaching, and other opportunities where learners receive feedback from an experienced instructor. Historically, MI training opportunities begin with in-person workshops that are conducted for one to several days, although more recently, online sessions have also been designed and delivered with more frequency since the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 [3,6-9]. Educational opportunities in MI are offered at various levels, starting with an introduction and progressing to those that advance learners to become instructors themselves [3,9]. Following an educational workshop, learners may record a practice MI interaction with another participant, a patient actor, or a patient. The audio recording is coded by someone qualified to use an assessment instrument. Learners may also receive additional coaching and targeted feedback from an experienced MI coach based on the assessed audio recording, preferably one who is a member of the Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers (MINT) [3]. A valid and reliable instrument for assessing a person’s skill using MI is the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity (MITI) coding system [10-12]. The MITI is composed of behavior counts and global rating scores used to assess learners’ competence and proficient use of MI [12]. Whether the recorded interaction documents a real-life patient interaction or a scenario with a patient actor, MITI coding and feedback from an experienced MI instructor regarding technical skills and interaction style are effective methods to enhance learners' skill development.

Before the onset of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, MI training was typically provided via in-person events. However, even before SARS CoV-2 restrictions were in place, other factors prevented some public health professionals from attending in-person MI workshops, such as difficulty getting time off from work and family obligations, and affording the costs associated with travel. Therefore, efforts to make high-quality MI instruction more accessible have increased, and online opportunities have become common [8,13-17]. While online instruction may improve the ease of access to MI workshops, there remains a variety of approaches (e.g., asynchronous or synchronous instruction), which may create disparities in levels of learner engagement and skill acquisition [7,18-21].

Due to the acceptance and increasing use of online MI instruction, it is necessary to evaluate and report on the effectiveness of different pedagogical methods to ensure the fidelity of the teaching and learning outcomes. Currently, there is limited research comparing the effectiveness of in-person MI workshops to that of online MI instructional opportunities. Data from two relevant studies [15,22]compared the learners’ knowledge, skills, and spirit of groups attending MI training workshops using in-person, online pedagogies, or a control group. Their results showed that the two groups that participated in training obtained comparable outcomes, despite the differences in instructional delivery.

However, these results are somewhat limited as participants were not placed in their groups using a randomized process. Therefore, a participant’s self-selected learning preference for in-person versus online instruction played a role in which of the groups they joined and likely had an impact on their learning outcomes. As online MI learning options become more common, there may be fewer in- person opportunities. Therefore, it is important to ascertain whether a meaningful difference in MI skill acquisition exists between online and in-person experiences. The current study attempted to control for self-selection bias for learning preferences by randomizing participants into two different instructional groups.

The primary aim of this study was to compare the MI technical skill and relational skill proficiency of two groups who were randomized into in-person and synchronous online training experiences as measured by MITI 4.2.1. The secondary aim was to compare preferences between instructional formats pre- and post-training, as well as to compare participant satisfaction. This study aims to establish the fidelity of online MI instruction using a standardized measure along with self-reported preferences and satisfaction. This will then enable MI instructors to provide evidence-based distance education and offer learners in geographically rural or low-resource areas across the country more opportunities to develop high-quality MI skills.

Materials and Methods

This experimental study evaluates differences in learning outcomes, preferences, and satisfaction between learners who were randomly assigned to one of two MI educational groups. Institutional review board approval was obtained #HE17103.

Procedures and Participants

All recruitment materials, emails, and electronic fliers included information about the total number of accepted participants, training schedules (days, times, and locations), and all potential participants were informed that training group assignments would be randomly created rather than based on personal preference. The first 40 registrants who completed both the consent to participate and the initial survey were randomized into two instructional groups (n = 20 per group) using a sequential numbering system. The remaining individuals were placed on a waitlist for the study. A cap of 20 participants per instructional group was pre-established based on the expectation of attrition and the desired ratio of learners to instructors. Training was provided as scheduled. A member of the research team regularly communicated with participants through email to respond to questions and remind them of training dates, times, and locations.

After finishing their training sessions, participants were immediately asked to complete a post-training survey. Online participants completed a Qualtrics survey, and in-person participants completed a paper survey. In addition to items from the pre-survey, participants were asked about their level of satisfaction with the training.

After their training sessions, learners were randomly paired with other group members so that they could each conduct practice MI interviews with one another. Once they completed their post-training survey, learners were then asked to demonstrate their new skills. They were given one hour to complete a recording of their interview session. Each learner had thirty minutes to be the “Motivational Interviewer” and thirty minutes to be a “patient/client.” Participants were instructed to choose a behavior about which they were ambivalent (something they might want to change but have been unable to do so). The online group was then put into virtual breakout rooms. Each pair was responsible for recording their interactions and submitting a completed recording. Recording devices were given to the in-person group and returned when they finished. Recordings were then randomly assigned to one of two, MITI coders who were blinded to the instructional method. Coders used the MITI 4.2.1 to measure the proficiency of participants’ MI skills [12,23].

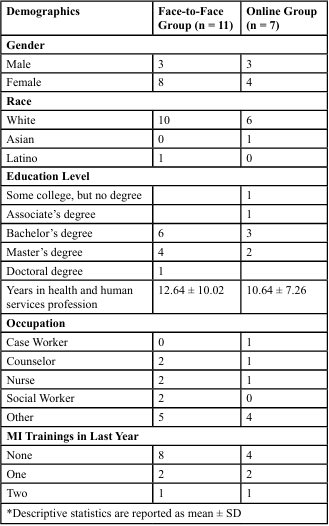

The initial sample for this study was 40, however after several participants dropped out, the final sample included eighteen participants, with six males and twelve females. Participants were at least 18 years old (mean ± SD: 39.5 ± 11.75), and all worked in public health or related professions. Participants included individuals in the following professions: nurse (3), counselor (3), social worker (2), case manager (1), and other (9). See table 1 for additional demographic information. Participants were recruited through email and word-of-mouth from several local and state public health agencies.

A total of 69 individuals registered to take part in this study. All registered individuals were randomly placed into one of two instructional groups: online or in-person, and the first twenty for each instructional group were informed that they would receive training (n=40) and the rest were placed on a waitlist (n=29).

Of the 20 individuals who were placed in the in-person MI training group, 18 completed the initial survey. Between the time of completing the initial survey and their first training session, three dropped out. An additional four participants did not attend the first training session, which left 11 participants. All 11 participants completed both days of MI training. The rate of completion through the final recording exercise for the in-person group was 55%.

Of the 20 participants in the online MI training group, 15 completed an initial survey. Three participants did not attend the first training session, two dropped out after completing one training session, and an additional two dropped out after completing four of the six sessions. Of the remaining eight participants, three completed five out of the six training sessions, and five people completed all the sessions. Three participants who completed most, but not all, of the sessions were not able to record practice interviews. One of the remaining three participants was dropped from the study, having not completed a recording or the post-training survey. Ultimately, the five participants who completed most or all the training and submitted audio recordings are included in this MI analysis, whereas seven participants are included in the survey data analysis. The rate of completion through the recording for the online group was 20%.

MI Instructional Description

Both MI groups completed 14 hours of instruction. The in-person sessions were conducted over two days; each day was eight hours with a one-hour lunch break. We used Cisco WebEx to facilitate our synchronous online sessions. This platform choice was important to maintain a high degree of consistency in the pedagogical methods (e.g., instructor and/or learner interactions) between the groups as much as possible. Online sessions were conducted over six days and spaced every other day (Monday, Wednesday, and Friday), over three weeks. The first and last sessions were three hours in length, while the other four sessions lasted two hours each. Both training courses were conducted by an experienced professional who completed the Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers (MINT’s) Train New Trainers (TNT). This person developed and used a similar curriculum and pedagogy for both groups, including didactic material, interactive discussion, demonstration, and skill practice. When practicing skills, the trainer divided learners into small groups and visited each group to coach participants.

Evaluation Measures

Questionnaire

A pre-instruction survey (n=22 closed-ended items) included demographic (11 items), prior MI instruction (4 items), online or in- person learning preference (2 items), and self-reported knowledge of, confidence in, and MI skills (3 items). Immediately following completion, participants were asked about their instructional satisfaction (5 items), their learning preference (online versus in person), and to self-report their knowledge of, confidence in, and MI skills (3 items) as well as their participation comfort (1 item). Survey items were created under the supervision of two MI content experts and were further reviewed by two individuals with expertise in survey methodology.

MITI 4.2.1.

Audio recordings were evaluated by experienced coders using MITI 4.2.1. This tool consists of four global scores based on a five- point Likert scale. The four global scores were categorized into two summary scores, which evaluated the technical and relational aspects of MI. The technical portion of MI includes the degree to which learners are engaging with their partner to cultivate change talk and soften sustain talk. The relational portion includes the degree to which learners engage with their partner to build a therapeutic partnership and express empathy. The MITI 4.2.1 also facilitates the assessment of the number of times learners engaged in ten unique behaviors: giving information, persuading, persuading with permission, asking questions, simple reflection, complex reflection, affirming, seeking collaboration, emphasizing autonomy, and confronting. Lastly, coders determined summary scores for the relational and technical sections by averaging the two components within each category. The summary scores also included a calculation of the percent of complex reflections, the reflection-to-question ratio, the number of times MI adherent interactions occurred, and the number of times MI non adherent interactions occurred. Standards for several of the summary scores are embedded in the MITI 4.2.1 instrument. MITI thresholds for competency are categorized as “Fair” or “Good” based on the average score, calculated percent, and ratio. These scores are based on “expert opinion.” See Moyers et al., [10], for more information about the MITI instrument and its use.

Data Analysis

Demographic information for each participant was gathered and analyzed using SPSS (Version #29). An independent t-test was used to evaluate pre- and post-training scores on the MITI 4.2.1 four global scores, six summary scores, and ten behavioral counts. Additional dependent t-tests were conducted to evaluate pre-post test scores related to participant preference and satisfaction scores. An alpha level of p< 0.05 for each t-test was used to determine statistical differences.

Results

Global Ratings and Summary Scores

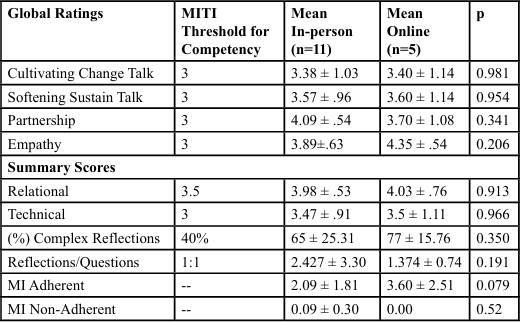

The mean MITI global rating and summary scores and independent sample t-test results for both groups are reported in Table 2. There was no significant difference in global rating scores (cultivating, softening, partnership, or empathy) between the two training groups. The in-person group did have a higher global partnership mean (4.09 ± .54) as compared to the in-person group (3.70 ± 1.08). Whereas, the online group had a higher global empathy mean score (4.35 + .54) when compared to the in-person group (3.89 ± .63).

Relational scores for the in-person group were 3.98±.53 while the online group was 4.03±.76. The technical scores for the in-person group were 3.47±.91 while the online group score was 3.5±1.11. There was no significant difference between the relational (t(14)= .017, p=.913) and technical scores (t(14)= .010, p=.966) in either group’s recorded interactions. Additionally, both groups had mean scores above the established MITI threshold for competence (“Fair”=3.5) for relational (M=3.59 ± .87) and (“Fair”=3.0) for technical (M=3.79 ± .84) global scores. The mean MITI percentage of complex reflections, reflections to questions, MI adherent, and MI non-adherent for both groups, along with the results of an independent sample t-test, are reported in Table 2. MITI proficiency thresholds are also represented in Table 2. Both training groups scored over the “good” MITI thresholds for competence based on the percentage of complex reflections. The in-person group had a higher ratio of reflections to questions when compared to those in the online group. The online group had more MI-adherent behaviors, such as emphasizing autonomy, seeking collaboration, and affirming, compared to the in-person group.

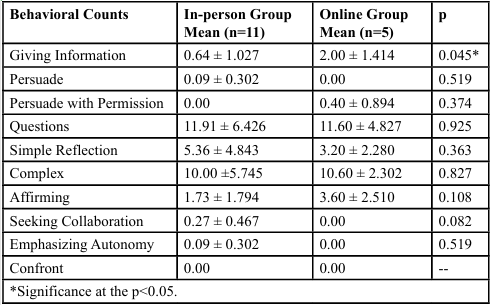

Behavior Counts

Table 3 shows mean MITI behavior counts as well as the results of an independent t-test for both groups. Giving information was the only behavior count with statistical significance (t(14)= 2.19, p=0.045). The online group demonstrated a higher frequency of giving information, affirming, and persuading with permission as compared to the in-person group. The in-person group showed a higher rate of simple reflections, seeking information, and autonomy.

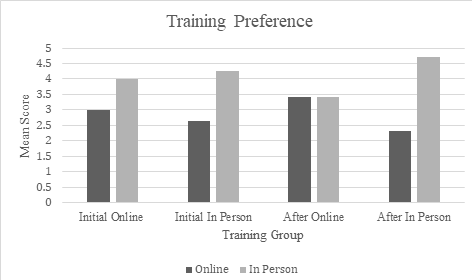

Preference and Satisfaction

Participant training modality preferences are reported in Figure 1. When comparing means, the in-person group preferred in-person over online training in both the pre- and post-surveys with an increase in preference for in-person training after completing the training (4.27 + .90, 4.7 + .67). The in-person group preference for online training decreased from baseline to post-training (2.64 + .81, 2.3 + .95). The online group preference for online training increased slightly from baseline to post-training (3+ 1.29, 3.43 + .98). Whereas, the online group preference for in-person training decreased from baseline to post-training (4 + .82, 3.43 + .98).

When comparing the overall means of both training groups from baseline to post-training, there is a marked, albeit stable, preference for in-person training. The mean preference pre training score for the online group was 2.78±1.0 while the post training score was 2.76±1.09. The mean score for the pre training for the in-person group was 4.17±0.86 while the post training score was 4.18±1.01.

Lastly, the overall mean satisfaction score was 4.59 ±.71. In-person learners (5.0±0.0) were more satisfied when compared to online learners (4.0±.81) t(15) =3.9; p = .001). The online group were less satisfied (3.86 ± .69) with the length of training when compared to the in-person group (4.40±1.07) t (15) =-1.17; p=.260).

Open-ended questions were asked about participation satisfaction. Both groups provided mixed feedback. Many in-person participants reported enjoying the training. One participant wrote, “I needed this training,” while another wrote, “I really enjoyed the in-person training as it gave me an opportunity to ask questions and interact with participants,” and “the trainer was extremely prepared and knowledgeable.” Another participant said the in-person method was best based on the type of skills being taught. They felt that, “when it comes to skills and learning like what was taught at this training, I would definitely prefer an in-person training over online.” On the other hand, one in-person participant felt that they needed more time to digest all of the information they were presented. Another person wrote, “I wish it would have been spread out (over more) days instead of two intense eight-hour days - easier to learn and practice.” Another person agreed writing, “eight hours was way too long” for a single training session. The online group shared both positive and negative feedback as well. Many participants liked the online option due to its accessibility. One participant wrote, “I liked that we were able to do this online because it was more convenient for me during my work schedule to not have to drive to the classroom. I liked the online format and interactions.” Another was surprised by their positive experience and wrote, “I actually kind of liked the way we did it online with other people from other locations.” Having the online training broken up over the course of six sessions was also popular with respondents. Still, half of the online training respondents indicated that they would prefer in-person training. One wrote, “It would have been better doing face-to-face.” Another agreed and noted, “Online was a little more difficult because I felt like people ended up leaving and people didn't interact as much.” An additional participant said that this type of training would be better in person since it involves non-verbal communication cues that are difficult to discern when online. Another issue mentioned by online participants was technical challenges that felt like a waste of training time.

Discussion

Motivational interviewing, an evidence-based practice used with patients or clients to promote health, relies on a complex set of interpersonal communication skills. This study aimed to evaluate the learning and skill outcomes in MI among participants randomized into either an online, synchronous, or in-person learning group. A secondary aim of this study was to evaluate learning preferences and participant satisfaction.

For the primary aim, the results from this study are similar to the results from previous work [15], even after randomization of participants. Comparable outcomes were observed in the acquisition of MI skills between in-person and online synchronous learners. These findings are promising in light of the growing trend toward delivering evidence-based training in health promotion, such as MI, through online modalities. One difference that was notable is the behavioral count of giving information. The online synchronous group had significantly higher counts for giving information. This difference may be caused by the loss of many visual cues and non verbal exchanges when interacting with someone online. As the demand and use of telehealth increases, MI trainers and practitioners will need to pay more attention to giving unsolicited information to patients.

Interactions between practitioner and patients or clients rely on both verbal and non-verbal communication. When interacting in-person, non-verbal cues—such as body language, facial expressions, and gestures—tend to be more prominent than in virtual interactions. These verbal and non-verbal elements are integral to the effective use of MI, and missing a large portion of communication through a virtual interaction may hinder the practitioner’s effective use of MI. A potential notable concern in using the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity (MITI) 4.2.1 coding system to assess practitioner competence is its sensitivity to variations in these communicative behaviors. Specifically, the nuanced interplay between a practitioner’s language, tone, and non-verbal cues may be difficult to accurately capture and evaluate without direct observation. This challenge may hinder the ability to discern subtle yet meaningful differences in MI skill proficiency.

While MITI 4.2.1 remains a useful tool for measuring foundational or entry-level competencies of the practitioner, the tool does not consider a patient or client's non-verbal communication [12]. Identifying a client's non-verbal language can help coders assess how the practitioner's approach and skills are affecting the client [12]. Another limitation of MITI 4.2.1 is that it consists of one fewer and broader global ratings and one fewer behavioral category than the previous version (MITI 3.1) used by Mullin et al. [15]. This makes comparisons between studies published using previous versions difficult [12]. However, a practitioner's overall style, MI fluency, and ability to develop therapeutic relationships can still be assessed and compared. Using a Likert scale to measure how successfully a practitioner performs is a subjective practice, which is why behavioral counts are also assessed to provide another vantage point and to further measure practitioner competence. While the MITI coding system may not provide as detailed an assessment as another validated instrument, the Motivational Interviewing Skill Code (MISC), which utilizes multiple recorded segments and coding sessions [12], the MISC is substantially more burdensome. Therefore, the MITI is more frequently used to expedite assessments and provide more timely feedback to learners. Additional research is needed to determine if the MITI 4.2.1 is sensitive enough to identify variances within an audio recording. Such an evaluation of the MITI coding system might help substantiate the validity of the comparison between synchronous online and in-person training methods.

For the secondary aim of this study, we hypothesized that most participants would prefer in-person instruction. The pre-training survey supported our hypothesis. However, it is interesting to note that our post-training survey showed that those who completed their training virtually reported an increased preference for online sessions. This response, along with elevated levels of satisfaction with the sessions, was indicative of a good participant experience and is consistent with other research reported on this topic [24]. However, it is also important to note that our participants' learning preferences may have influenced our study's high dropout rate. Anecdotally, several emails received during the registration process were related to whether a participant could select their training group despite the recruitment materials specifically stating that participants would be randomized into one of the two groups. Yet some participants may have registered with the hope that they would end up being randomized into their preferred training group. If that did not happen, these individuals may have decided to drop out [7,20,21].

An important factor when considering training modalities is the variety of learning styles demonstrated by individuals (e.g., auditory, visual, kinesthetic, and reading/writing). Learner preferences for instructional methods (e.g., in-person, synchronous, or asynchronous online) must also be carefully considered [18,19]. Participant learning preferences may conflict with logistical factors such as cost, time, and accessibility, and while learning preferences are very important, the benefits of accessibility of instruction in evidence- based practices such as MI may outweigh the costs of not matching learning preferences [8,13-17].

Other important considerations for online synchronous training are the length of the training sessions, the number of days spaced between the training sessions, the learners’ interaction with the other participants and the trainer, and the ease of using the technology [24]. In this study, the first and last training sessions were three hours and the other sessions were two hours. Due to the trainers schedule we had a one week break between the first set of trainings and the second set. This may have contributed to the attrition in the online group.

MI Training Opportunities

In-person workshops have traditionally been the preferred method of instruction among MI instructors. However, there is a growing need to extend access to qualified MI training for public health professionals in geographically isolated or underserved areas. Given the critical importance of evidence-based training in rural settings, online instructional methods have been increasingly developed and adopted. The emergence of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic further accelerated this shift, prompting a rapid and widespread transition to online training modalities. This pedagogical shift has introduced both challenges and opportunities for trainers and learners, reshaping the delivery and accessibility of MI education [6,7,18,21,25].

Strengths

This study demonstrates several strengths. First, randomization eliminated self-selection bias in terms of training modality. Another advantage was the pedagogical consistency between the learning groups. The same instructor taught both and all of our participants completed the same number of training hours. Therefore, the confidence in the comparison of outcome measures between groups is more likely related to the difference in training modality versus other factors. The Cisco WebEx platform allowed all participants to access and use the same system simultaneously. The use of web cameras also facilitated improved interactions between participants and their instructor. Additionally, the breakout room feature was essential as it enabled participants to practice their interview skills with each other, similar to the in-person group experience.

Limitations

This study did have limitations. Our sample size was intended to be like that of the Mullin et al. study [15]. However, though we attempted to oversample, our dropout rate was higher than expected and reduced the number of participants. The high number of dropouts might be due to training times/availability, or learners may have preferred one learning modality over the other and were disappointed when randomly placed into the other group. The small sample size in this study limited the power to detect significant differences between MITI scores, modality preference, and satisfaction with the course. Another limitation of this study was not having participants perform an audio recording of themselves using MI with a client prior to beginning their training. Having a pre- and post-assessment of each participant's skills would have been beneficial in measuring a change in MI skills because of the training. It would have also helped us further determine any differences in skill development between groups. This study is reflective of public health professionals and is not generalizable to other professionals.

Further Research

Further research on whether online synchronous training is an equally effective modality for delivering MI training needs to be conducted, especially studies involving larger sample sizes and randomization. Longitudinal comparisons between online and in-person MI skills retention are also important. Furthermore, as asynchronous training methods continue to advance, another study in which participants are randomized into three experimental groups— asynchronous, synchronous, and in-person, and a control group would be helpful. More generally, research into further developments of the maintenance of MI training reliability would be especially useful so that more public health professionals are able to access high-quality, evidence-based training.

Conclusion

This study provides evidence that public health professionals can acquire Motivational Interviewing (MI) skills through both in-person and synchronous online training formats. Several factors contribute to the success of online synchronous and in-person learning, including session length and duration, curriculum, and the ability of a web platform to engage online learners using similar techniques to those used during in-person training. Many learners preferred and were more satisfied with in-person training compared to online synchronous training; however, when access (travel, time away from work/family, cost, etc.) is a concern, online synchronous training may be an adequate substitute. Expanding online training opportunities may enhance access to MI education for practitioners in rural or geographically remote areas, while also addressing barriers such as cost, scheduling conflicts, and time away from home. However, as this is only the second known study comparing these two training modalities, further research is warranted—particularly longitudinal studies with larger and more diverse samples—to better understand the long-term effectiveness and feasibility of online MI training.

Competing Interests and Source of Funding

The authors declare no competing interests with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments:

We would like to acknowledge Amanda Fairweather Campbell, MS, for her valuable contributions to this work as a graduate assistant during her master’s studies at NDSU. We are also grateful to Scott Nyegaard, MS, a member of the Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers, for providing excellent training in motivational interviewing.

References

Emmons, K. M., & Rollnick, S. (2001). Motivational interviewing in health care settings: Opportunities and limitations. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 20(1), 68-74. View

Mangabady, H., Khosravi, S., Nodoushan, A. J., Mahmoudi, M., & Shokri, A. (2014). Study on efficacy of group Motivational Interviewing in reducing impulsivity among drug users on methadone treatment. Journal of Community Health Research, 2(4), 301-308. View

Miller, W., & Rollnick, S. (2023). Motivational interviewing: Helping people change and grow (4th ed.). Guilford Press. View

Morton, K., Beauchamp, M., Prothero, A., de Bruin, M., Demarteau, N., Sniehotta, F. F., & Pedersen, L. (2015). The effectiveness of Motivational Interviewing for health behaviour change in primary care settings: A systematic review. Health Psychology Review, 9(2), 205-223. View

Söderlund, L. L., Madson, M. B., Rubak, S., & Nilsen, P. (2011). A systematic review of Motivational Interviewing training for general health care practitioners. Patient Education and Counseling, 84(1), 16-26. View

Billett, S., Leow, A., Chua, S., & Boud, D. (2023). Changing attitudes about online continuing education and training: A Singapore case study. Journal of Adult and Continuing Education, 29(1),106-123. View

Cassidy, D., Edwards, G., Bruen, C., Delaney, L., & Flaherty, G. (2023). Are we ever going back? Exploring the views of health professionals on postpandemic continuing professional development modalities. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 43(3), 172-180. View

Fontaine, G., Cossette, S., Heppell, S., Boyer, L., Mailhot, T., Simard, M., & Tanguay, J. (2016). Evaluation of a web-based e-learning platform for brief Motivational Interviewing by nurses in cardiovascular care: A pilot study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(8), e224. View

Madson, M., Loignon, A., & Lane, C. (2009). Training in Motivational Interviewing: A systematic review. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 36, 101-109. View

Moyers, T., Martin, T., Manuel, J. K., Hendrickson, S. M., & Miller, W. R. (2005). Assessing competence in the use of Motivational Interviewing. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 28(1), 19-26. View

Moyers, T., Martin, T., Manuel, J. K., Miller, W. R., & Ernst, D. (2010). Revised global scales: Motivational Interviewing treatment integrity 3.1.1 (MITI 3.1.1). Draft manuscript. View

Moyers, T., Rowell, N., Manuel, J. K., Ernst, D., & Houck, J. M. (2016). The Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity code (MITI 4): Rationale, preliminary reliability and validity. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 65, 36-42. View

Khanna, M. S., & Kendall, P. C. (2015). Bringing technology to training: Web-based therapist training to promote the development of competent cognitive-behavioral therapists. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(3), 291-301. View

Mitchell, S., Heyden, R., Heyden, N., Schroy, P., Wiecha, J., & Deloria-Knoll, M. (2011). A pilot study of Motivational Interviewing training in a virtual world. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 13(3), e77. View

Mullin, D. J., Saver, B., Savageau, J. A., Forsberg, L., & Forsberg, L. (2016). Evaluation of online and in-person Motivational Interviewing training for healthcare providers. Families, Systems, & Health, 34(4), 357-366. View

Schechter, N., Butt, L., Wegener, S. T., Haines, K. J., Kharrazi, H., & Lehmann, L. S. (2021). Evaluation of an online Motivational Interviewing training program for rehabilitation professionals: A pilot study. Clinical Rehabilitation, 35(9), 1266-1276. View

Singh, T., & Reyes-Portillo, J. A. (2020). Using technology to train clinicians in evidence-based treatment: A systematic review. Psychiatric Services, 71(4), 364-377. View

Fernandez, C. S., Green, M. A., Noble, C. C., Steffen, L. E., & Slattery, E. L. (2021). Training "pivots" from the pandemic: Lessons learned transitioning from in-person to virtual synchronous training in the clinical scholars leadership program. Journal of Healthcare Leadership, 13, 63-75. View

Giesbers, B., Rienties, B., Tempelaar, D., & Gijselaers, W. (2014). A dynamic analysis of the interplay between asynchronous and synchronous communication in online learning: The impact of motivation. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 30(1), 30-50. View

Lawn, S., Zhi, X., & Morello, A. (2017). An integrative review of e-learning in the delivery of self-management support training for health professionals. BMC Medical Education, 17(1), 1-16. View

Sujon, H., Uzzaman, M. N., Banu, S., Hossain, M. M., & Alam, M. Z. (2022). Professional development of health researchers during the COVID-19 pandemic: Challenges and prospects of synchronous online learning. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 42(1), e1-e2. View

Schaper, K., Woelber, J.P., & Jaehne, A.. (2024). Can the spirit of motivational interviewing be taught online? A comparative study in general practitioners. Patient Education and Counseling., 125. View

Owens, M. D., Rowell, L. N., & Moyers, T. (2017). Psychometric properties of the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity coding system 4.2 with jail inmates. Addictive Behaviors, 73, 48-52. View

Chaker, R., Hajj-Hassan, M. & Ozanne, S. (2024). The Effects of Online Continuing Education for Healthcare Professionals: A Systematic Scoping Review. Open Education Studies, 6(1), 20220226. View

Martin, P., Kumar, S., Abernathy, L., Browne, M., Quinlan, F., & Kozan, K. (2018). Good, bad or indifferent: A longitudinal multi-methods study comparing four modes of training for healthcare professionals in one Australian state. BMJ Open, 8(8), 1-8. View