Journal of Public Health Issues and Practices Volume 9 (2025), Article ID: JPHIP-248

https://doi.org/10.33790/jphip1100248Research Article

Biopsychosocial and Economic Consequences of Long COVID: A Four-Year Longitudinal Analysis

Ibrahim Alliu1*, Dr.PH, Subash Thapa2, MPH, Samuel Opoko3, PhD, and Lili Yu4, PhD,

1Assistant Professor, Jiann-Ping Hsu College of Public Health, Department of Biostatistics, Epidemiology and Environmental Sciences, Georgia Southern University, Statesboro, Georgia, United States.

2Doctoral Candidate, Jiann-Ping Hsu College of Public Health, Department of Biostatistics, Epidemiology and Environmental Sciences, Georgia Southern University, Statesboro, Georgia, United States.

3 Professor of Health Policy & Community Health, Jiann-Ping Hsu College of Public Health, Health Policy & Community Health, Georgia, Southern University, Statesboro, Georgia, United States.

4Professor of Biostatistics, Jiann-Ping Hsu College of Public Health, Department of Biostatistics, Epidemiology and Environmental Sciences, Georgia Southern University, Statesboro, Georgia, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Ibrahim Alliu, Assistant Professor, Jiann-Ping Hsu College of Public Health, Department of Biostatistics, Epidemiology and Environmental Sciences, Georgia Southern University, Statesboro, Georgia, United States.

Received date: 24th September, 2025

Accepted date: 13th December, 2025

Published date: 15th December, 2025

Citation: Alliu, I., Thapa, S., Opoko, S., & Yu, L., (2025). Biopsychosocial and Economic Consequences of Long COVID: A Four-Year Longitudinal Analysis. J Pub Health Issue Pract 9(2): 248.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Background: The multi-year consequences of Long COVID remain incompletely characterized, particularly with respect to healthcare utilization and economic burden.

Methods: We conducted a prospective longitudinal analysis of 4,038 respondents from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) Panel 24 (year 2019–2022). Participants were classified into three groups: Long COVID (symptoms ≥3 months), COVID-recovered, and no COVID. Hierarchical linear models were used to estimate four-year trajectories of perceived health, psychological distress (K6 scale), and inflation-adjusted healthcare expenditures, adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, insurance status, baseline self-rated health, and comorbidity burden.

Results: After full adjustment, COVID-19 status was not independently associated with perceived health or psychological distress over time, and no evidence of differential symptom progression was observed between the groups. In contrast, healthcare expenditures diverged significantly by COVID status. Individuals with Long COVID experienced a substantially faster rate of spending growth compared with COVID-recovered and No-COVID respondents, confirmed by a strong time-by-group interaction (p < 0.0001), independent of baseline health and sociodemographic factors.

Conclusions: In this nationally representative cohort, baseline health status explained most variation in long-term health and psychological outcomes following COVID-19 infection, whereas Long COVID was independently associated with escalating healthcare costs. These findings suggest that, in this cohort, the dominant long-term sequela of Long COVID is economic rather than symptomatic, with important implications for healthcare financing, disability policy, and post-acute care planning.

Keywords: Health Expenditures; Psychological Distress; Hierarchical Linear Modeling; Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC); Chronic Illness.

List of Abbreviations: MEPS, PASC, HLM, K6, COVID

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, initiated by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, has precipitated a global health crisis of unprecedented scale. Despite extensive research and public health responses to the acute phase, a massive secondary epidemic – Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC), also known as Long COVID has followed in the footsteps of the acute epidemic [1]. It is characterized by a symptom profile of over 200 recurring and often recurring symptoms, including profound fatigue, neurocognitive impairment ("brain fog"), and cardiorespiratory dysfunction. Long COVID happens in a high percentage of individuals regardless of the severity of the initial illness [2,3]. This condition is not a simple and prolonged recovery, but a complex, multisystemic disease which is likely driven by several overlapping pathophysiological mechanisms, including viral persistence, immune dysregulation, autoimmunity, and endothelial dysfunction [2,4].

A large body of literature highlights the profound consequences of Long COVID. Cross-sectional and short-term cohort studies have consistently described its disproportionate impact across different domains. From a biological standpoint, Long COVID patients have high rates of new onset of chronic illness, including cardiovascular, metabolic, and neurologic disease, with substantially enhanced utilization of medical care [5,6]. Psychologically, the condition is strongly associated with elevated rates of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder, driven by the burden of chronic illness and uncertainty [7]. Socially and financially, Long COVID related work limitation has caused a huge loss of workforce participation, by the millions, due to the inability to work, creating tremendous economic insecurity on the family level, as well as financial instability on the broader level [8].

Current literature lacks a comprehensive longitudinal analysis of health, financial stability, employment, and disability outcomes. With most studies limited to one year of follow-up, the multi-year trajectory of Long COVID remains unmapped, specifically whether associated health and financial losses improve, worsen, or remain stable overtime. This knowledge is essential for predicting future healthcare needs, planning efficient social support, and determining the pandemic's actual, long-term societal cost.

This study fills this crucial knowledge gap through one of the first multi-year, nationally representative, longitudinal studies of the outcomes of Long COVID. Using four years of Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) data, we go beyond short-term, static measures. We use hierarchical linear modeling to specifically model and compare over time the paths of perceived physical health, psychological distress, and healthcare spending for three different groups: persons with Long COVID, persons who recovered from acute COVID, and a No COVID control group. By doing so, our goal is to characterize the long-term burden of Long COVID, determining whether its impact represents a persistent deficit, a gradual recovery, or an accelerating crisis.

Materials and Methods

Research Design and Data Source

This study utilized a prospective longitudinal cohort design to examine the MEPS Panel 24 data. MEPS is a nationally representative survey of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population conducted by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).

Panel 24 was selected specifically for its unique timing: data collection spanned from 2019 to 2022, capturing the pre-pandemic baseline (2019), the acute emergence of COVID-19 (2020), and the subsequent post-pandemic period (2021–2022). Unlike electronic health record studies based on clinical encounters, MEPS utilizes a panel design with fixed rounds of interviews (five rounds over two years) regardless of healthcare utilization. This design minimizes selection bias associated with healthcare-seeking behavior and ensures the capture of outcomes for individuals who may not frequently visit medical providers.

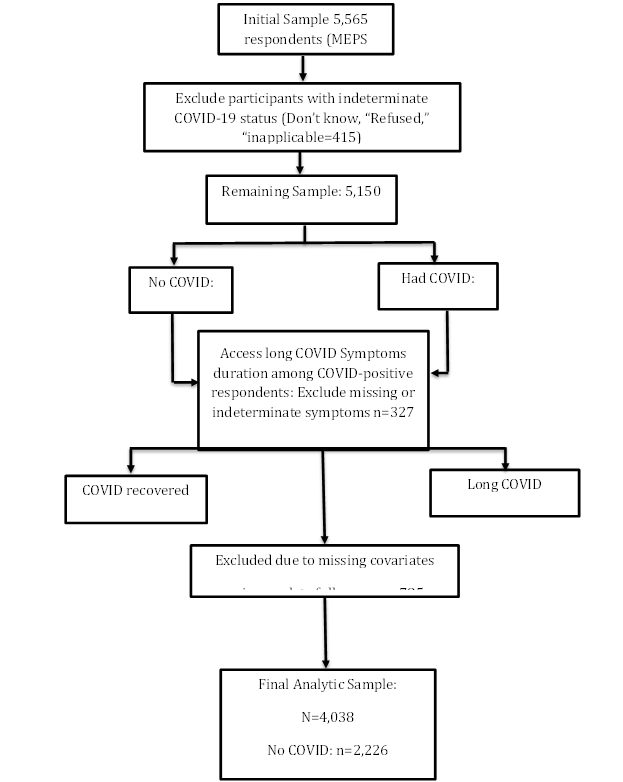

Study Population and Cohort

All respondents enrolled in MEPS Panel 24 were eligible for inclusion regardless of age if they had valid information on COVID-19 history and contributed at least one outcome measure during follow-up. Individuals with indeterminate COVID-19 history (e.g., “don’t know,” “refused,” or “not ascertained”) were excluded. Among respondents reporting COVID-19 infection, individuals with missing or indeterminate symptom-duration information were also excluded. The analytic sample was classified into three mutually exclusive cohorts: (I) No COVID (II) COVID-recovered, and (III) Long COVID, latter defined as persistent symptoms lasting at least three months or longer. A participant flow diagram summarizes sample inclusion, exclusion, and Participant inclusion, exclusions, and final cohort assignment are summarized in Figure 1.

Measures

COVID-19 history and symptom persistence were based on self-reported MEPS items. Long COVID was operationalized using a symptom-duration threshold of ≥3 months, consistent with international clinical definitions of post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection [9,10]. Respondents reporting infection without prolonged symptoms were classified as COVID-recovered, and those reporting no infection over the study period formed the reference group.

Outcomes

Three longitudinal outcomes were modeled annually across four waves:

1. Perceived Health Status: In the MEPS, perceived health was measured using the standard five-point Likert scale, where respondents rated their overall health. The scale ranges from 1 (Excellent) to 5 (Poor) with lower scores indicating better perceived health.

2. Psychological Distress: Measured using the Kessler-6 (K6) scale, a continuous score where higher values indicate greater distress. The K6 was selected since it is a well-validated and widely used instrument for assessing non-specific psychological distress in population health surveys.

3. Total healthcare expenditures, adjusted to 2024 U.S. dollars using Consumer Price Index values from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and log-transformed to normalize the cost distribution [11].

Covariates

Covariates were selected a priori based on epidemiologic relevance and prior research. Baseline health status and baseline comorbidities were defined using 2019 data to preserve temporality. A comorbidity index was constructed from diagnoses of hypertension, diabetes, asthma, heart disease, and stroke. Additional covariates included age, sex, and time-varying insurance status. Race/ethnicity was modeled as a categorical variable with Non-Hispanic White as the reference group to enhance interpretability and statistical stability in U.S. population analyses [12].

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were summarized using survey-weighted means and proportions. Group differences were assessed using survey-adjusted chi-square tests for categorical variables and survey adjusted ANOVA for continuous variables.

Longitudinal changes in perceived health, psychological distress, and healthcare expenditures were analyzed using hierarchical linear models (mixed-effects models), with repeated measurements nested within individuals. Random intercepts and random slopes for time were specified to account for within-person correlation and unequal numbers of observations per participant. Time-by-group interaction terms were included to test for differential trajectories across COVID-19 cohorts. Models were estimated using restricted maximum likelihood (REML) with robust (empirical) standard errors, consistent with best practices for longitudinal data analysis [13,14].

Survey weights were applied in descriptive analyses and normalized for mixed-effects regression by dividing each weight by the sample mean, ensuring population-level inference while stabilizing variance [12].

The analysis was conceptualized as a two-level model:

Level 1: Within-person Change

Yti= π0i+ π1i(Timet) + eti (1)

Where Yti is the outcome for person i at time t,

π0i is the baseline outcome,

π1i is the annual rate of change, and

eti is the residual error.

Level 2: Between-person Differences in change

This level models how the individual intercepts and slopes from Level 1 are predicted by the independent variables. The expanded equations are:

π0i= β00+ β01(LongCOVIDi)+β02(Agei) + β03(Sexi) + β04(Racei)+ β05(Insurancei) + β06 (Baseline_Healthi) r0i (2) π1i = β10 + β11(LongCOVIDi) + β12(Agei) + β13(Sexi) + β14 (Racei) + β15(Insurancei) + β16(Baseline_Healthi) r1i (3)

Here, β01 reflects baseline differences across COVID status groups, while β11 captures differences in rates of longitudinal change (time-by-group interaction). Random effects r0i and r1i represent unexplained variability in intercepts and slopes.

Handling of Missing Data

Missing data in outcomes and covariates were addressed using Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) within the mixed effects modeling framework. This approach retains participants with incomplete data under the Missing at Random assumption, reduces bias associated with listwise deletion, and produces efficient and unbiased estimates in longitudinal analyses [15-17].

Results

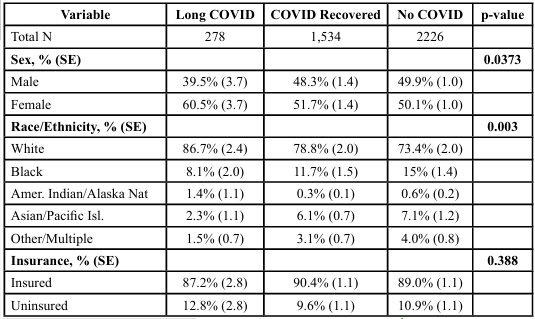

The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the analytic sample by COVID-19 status group are presented in Table 1. The weighted sample represented approximately 336.9 million individuals nationally, of whom 6.89% had Long COVID, 37.99% had recovered from COVID-19 without prolonged symptoms, and 55.13% reported no history of COVID-19. Significant differences were observed across groups for sex and race/ethnicity, while insurance coverage did not differ significantly across COVID categories.

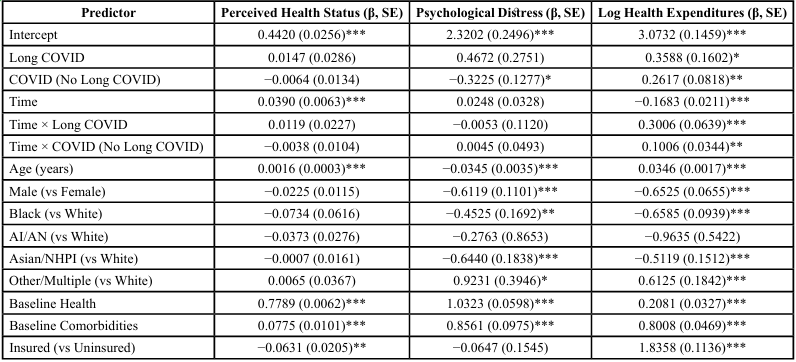

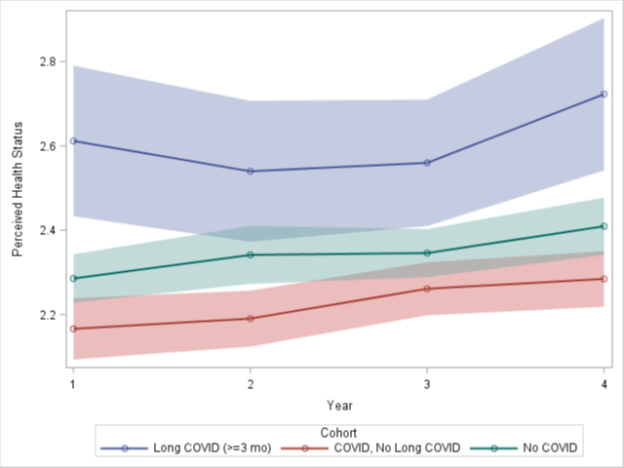

Longitudinal Trajectories of Health and Economic Outcomes Perceived Health Status Over Time

After adjusting for covariates, COVID-19 status was not significantly associated with perceived health (F(2, 9396) = 0.3, p = 0.7415), indicating that perceived health trajectories progressed in parallel across cohorts.

A highly significant main effect of time was observed (F(1, 4704) = 26.69, p < 0.0001), reflecting a general deterioration in self-rated health across all participants during the four-year follow-up period.

Baseline clinical characteristics were the dominant predictors of perceived health. Baseline self-reported health was the strongest determinant (F(1, 9396) = 15,864.2, p < 0.0001), followed by baseline comorbidity burden (F(1, 9396) = 58.78, p < 0.0001) and insurance status (F(1, 9396) = 9.45, p = 0.0021). Age was also independently associated with perceived health (F(1, 9396) = 27.65, p < 0.0001), whereas race/ethnicity was not significant after adjustment (p = 0.516).

Sex showed a borderline association with perceived health (F(1, 9396) = 3.79, p = 0.051) but did not meet conventional significance thresholds. Mean trajectories of perceived health by COVID-19 status over time are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 2: Trajectory of Mean Perceived Health Status (1=Excellent, 5=Poor) over four years, stratified by COVID-19 status group.

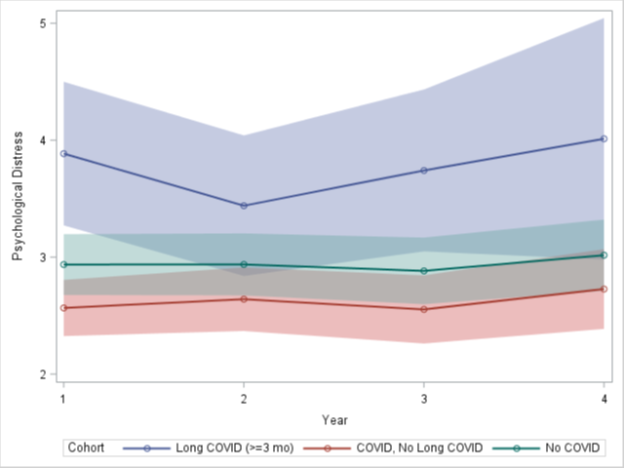

Psychological Distress Trajectories

In contrast to perceived health, COVID-19 status was independently associated with psychological distress in fully adjusted models (F(2, 4406) = 5.91, p = 0.0027). However, there was no evidence of differential change over time by COVID-19 group (Time × COVID interaction: F(2, 4406) = 0.01, p = 0.9936), indicating that distress trajectories evolved in parallel across cohorts.

While COVID-19 classification predicted cross-sectional differences in distress, the effect was not driven by an accelerating burden among individuals with Long COVID. Instead, psychological distress appeared to be shaped primarily by clinical vulnerability and sociodemographic characteristics. Age (F(1, 4406) = 97.63, p < 0.0001), sex (F(1, 4406) = 30.89, p < 0.0001), and race/ethnicity (F(4, 4406) = 6.12, p < 0.0001) were significant predictors, as were baseline health (F(1, 4406) = 297.63, p < 0.0001) and baseline comorbidity burden (F(1, 4406) = 77.10, p < 0.0001). Insurance status was not significantly associated with psychological distress after adjustment (p = 0.675). Group-specific trends in psychological distress over time are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 3: Trajectory of Mean Psychological Distress (K6 Score) over four years, stratified by COVID-19 status group.

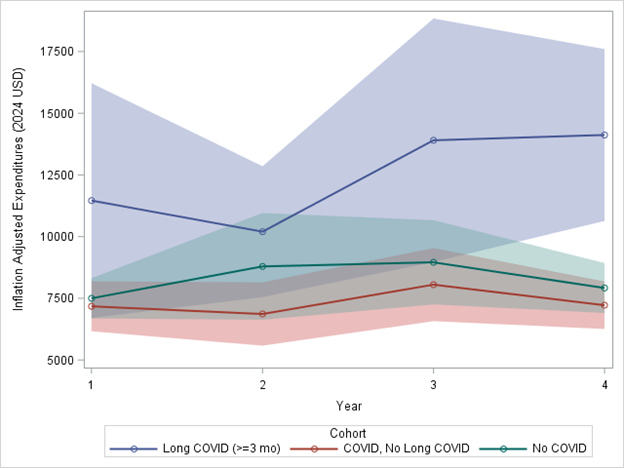

Escalating Economic Burden Associated with Long COVID

In the fully adjusted mixed-effects model of log inflation-adjusted healthcare expenditures, COVID-19 status was independently associated with healthcare spending (F(2, 9412) = 6.45, p = 0.0016). Importantly, a highly significant Time × COVID status interaction (F(2, 9412) = 13.10, p < 0.0001) indicated that expenditure trajectories diverged significantly across cohorts.

Stratified interpretation of the interaction revealed that individuals with Long COVID experienced a progressively accelerating increase in healthcare expenditures over time relative to both COVID recovered and COVID-naive participants. In contrast, no parallel escalation was observed among individuals who recovered without persistent symptoms or among those who were never infected, with largely overlapping 95% confidence intervals across Time as shown in figure 4.

Baseline comorbidity burden was the strongest predictor of expenditures (F(1, 9412) = 291.92, p < 0.0001), followed by insurance status (F(1, 9412) = 261.37, p < 0.0001), age (F(1, 9412) = 423.28, p < 0.0001), sex (F(1, 9412) = 99.19, p < 0.0001), and race/ ethnicity (F(4, 9412) = 19.25, p < 0.0001). Baseline health status also remained a significant independent predictor (F(1, 9412) = 40.63, p < 0.0001). Longitudinal trends in inflation-adjusted healthcare expenditures across COVID-19 status groups are displayed in Figure 4.

Crucially, the persistence of the Time × Long COVID interaction after adjustment for baseline health and comorbidities demonstrates that escalating healthcare utilization among Long COVID patients is not fully explained by pre-pandemic medical vulnerability or socioeconomic status, but reflects a unique longitudinal burden associated with post-acute sequelae.

Figure 4: Trajectory of Mean Inflation-Adjusted Total Health Expenditures (2024 USD), with shaded 95% confidence intervals

Summary of Longitudinal Findings

In this nationally representative cohort, perceived health and psychological distress did not worsen more rapidly among individuals with Long COVID after adjustment for baseline health status, comorbidity burden, and sociodemographic characteristics. In contrast, healthcare expenditures diverged significantly over time, with individuals with Long COVID experiencing persistently accelerating costs relative to COVID-recovered and COVID-naive participants.

These findings demonstrate a clear dissociation between clinical trajectories and economic outcomes. While symptom-based indicators remained largely stable after accounting for pre-pandemic vulnerability, financial burden escalated independently among individuals with Long COVID. Collectively, the results suggest that the dominant long-term consequence of COVID-19 in this national cohort is economic rather than symptomatic, underscoring Long COVID as an emerging driver of chronic healthcare spending with important implications for patients, payers, and health systems. Adjusted fixed-effect estimates from the mixed-effects models are presented in Table 2.

Discussion

This nationally representative longitudinal analysis provides evidence that Long COVID is associated with a persistent and increasing financial burden, rather than with worsening self-reported health or psychological distress after adjustment for baseline health status and sociodemographic determinants. While individuals with Long COVID entered follow-up with poorer health and greater baseline vulnerability, their symptom trajectories did not significantly diverge over time from COVID-recovered or never- infected participants once these baseline factors were controlled. In contrast, healthcare expenditures increased at a significantly faster rate among individuals with Long COVID, indicating a sustained economic penalty associated with the condition.

Our findings extend prior cross-sectional and short-term utilization studies by demonstrating that the economic impact of Long COVID intensifies over time, independent of pre-pandemic frailty and comorbidity burden. Previous investigations have documented increased outpatient visits, prescription utilization, and emergency department use following SARS-CoV-2 infection [5,18]. However, most studies are limited to post-acute windows or health system specific cohorts. By contrast, our analysis reveals an accelerating expenditure trajectory over multiple years within a nationally representative panel.

This pattern is consistent with emerging conceptualizations of Long COVID as a disorder of persistent systems engagement rather than linear disease progression, characterized by diagnostic proliferation, fragmented care, and unresolved symptom clusters [2]. Such conditions generate cost through repeated clinical encounters without resolution, producing what economists describe as diagnostic intensity inflation rather than therapeutic care consolidation.

Importantly, this economic divergence persisted even after adjusting for self-rated baseline health and chronic disease burden, indicating that Long COVID is associated with elevated long-run healthcare costs beyond pre-existing vulnerability. These results suggest that Long COVID likely operates as a distinct health-economic phenotype, consistent with findings from Veterans Affairs cohorts, where cumulative costs have been documented despite controlling for service-connected disability and prior utilization [19].

A key and potentially counterintuitive finding of this study is that baseline health status and multimorbidity burden were the primary predictors of perceived health and psychological distress across all COVID-19 groups. After adjustment, COVID-19 status itself did not independently explain longitudinal symptom deterioration.

This aligns with mounting evidence that Long COVID is a disproportionately risk-concentrated condition, enriched among individuals with poorer pre-pandemic health, metabolic disease, and functional limitations [3,20]. Rather than representing a uniform biological syndrome, Long COVID likely reflects a complex interaction between viral injury and pre-existing vulnerability. In this regard, SARS-CoV-2 may plausibly act as a trigger within pre existing vulnerability pathways.

Our findings reinforce the ecological model of health resilience, in which prior physiological reserve determines post-infection recovery trajectories [21]. The relative absence of worsening symptom slopes among Long COVID participants does not undermine the legitimacy of ongoing illness; rather, it indicates that many symptoms persist without necessarily intensifying—a chronic state rather than a progressive one.

Although psychological distress varied significantly by COVID-19 status cross-sectionally, we did not observe diverging longitudinal distress trajectories by group. This suggests that mental health impacts of COVID-19 are driven largely by social context, economic disruption, and baseline psychosocial vulnerability rather than viral persistence.

This interpretation is consistent with longitudinal mental health research during the pandemic period, which shows that population level distress peaked early and stabilized thereafter [22]. Moreover, differences in psychological distress across COVID-19 groups may reflect survivor bias, health optimism following recovery, or post traumatic growth [23].

Thus, while Long COVID is associated with elevated psychological symptom burden, it does not appear to generate escalating distress independently. This distinction is essential to avoid pathologizing Long COVID as a uniform psychological syndrome and instead recognize mental health outcomes as socially mediated sequelae.

The policy implications of these findings are substantial. Health systems currently emphasize clinical management of Long COVID through specialty clinics, rehabilitation services, and symptom monitoring. However, our results demonstrate that Long COVID also represents a budgetary condition, with cost trajectories that diverge long after acute infection.

In 2022, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services explicitly recognized Long COVID as a major health systems challenge in its National Research Action Plan for Long COVID, yet federal insurance and disability frameworks remain underdeveloped. Our findings support the need for:

1. Expansion of disability eligibility criteria to recognize post-viral cost burden.

2. Long-term reimbursement planning for outpatient service inflation.

3. Employer-based accommodations for sustained productivity loss.

Failure to incorporate Long COVID into actuarial forecasting risks transforming a public health crisis into a prolonged fiscal one.

Further, the economic burden quantified here reinforces international cost modeling studies estimating billions in productivity losses and disability costs annually due to post-COVID conditions [24].

Strengths and Limitations

The study has some important strengths. We drew on a large, nationally representative longitudinal survey with observations beginning before the COVID-19 pandemic, which supports inference to U.S. adults and allows changes to be followed over time instead of inferred from a single wave of data. Key indicators, health, psychological distress and healthcare spending, were observed repeatedly over four years and multilevel models were used to describe their trajectories rather than isolated time points. The expenditure information was inflation-adjusted, which increases the relevance of the results for policy and planning. In addition, use of Full Information Maximum Likelihood to address missing data reduces, though does not fully remove, bias related to incomplete follow-up.

Several limitations should also be kept in mind. The analysis relied on secondary MEPS data. COVID-19 infection status, presence and duration of persistent symptoms, and perceived health were self reported, making them susceptible to recall error and reporting bias. Long COVID was not established based on clinical assessment or laboratory markers, so some misclassification is likely, including the possibility that respondents with chronic pre-existing conditions attributed ongoing symptoms to Long COVID. MEPS does not provide information on COVID viral variants, or severity of the acute episode, and therefore residual confounding is probable even after statistical adjustment. Also, attrition bias, particularly subsequent attrition, is likely if individuals with greater illness burden or socioeconomic instability are less likely to remain under observation. Nonetheless, the findings still provide adjusted associations within an observational design.

Conclusion

In this nationally representative longitudinal cohort, long-term health and psychological outcomes following COVID-19 infection were driven primarily by pre-pandemic health status rather than COVID-19 classification alone. In contrast, healthcare expenditures increased more rapidly among individuals with Long COVID, indicating a persistent and independent economic burden that extends across multiple years.

These findings indicate that pre-existing health vulnerability could shape symptom burden, whereas Long COVID primarily manifests as a sustained financial consequence within the healthcare system. The results, therefore, reposition Long COVID as both a clinical condition and an emerging driver of long-term healthcare costs.

Policy responses should reflect this dual role. Interventions that strengthen baseline population health, particularly among medically vulnerable groups, are essential for reducing downstream morbidity. At the same time, insurance design and disability policies must explicitly account for the sustained cost burden associated with Long COVID, including improved access to benefits, workplace accommodations, and mechanisms to limit out-of-pocket spending.

Notably, these conclusions persisted after adjustment for insurance coverage and inflation-adjusted expenditures, underscoring the robustness of the observed cost divergence. Together, the results highlight the importance of shifting Long COVID policy from a short-term clinical response toward a longer-term economic and social protection strategy.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank colleagues at the Jiann-Ping Hsu College of Public Health for their feedback and support during the development of this study.

References

Nalbandian, A., Sehgal, K., Gupta, A., Madhavan, M. V., McGroder, C., Stevens, J. S., Cook, J. R., Nordvig, A. S., Shalev, D., Sehrawat, T. S., Ahluwalia, N., Bikdeli, B., Dietz, D., Der Nigoghossian, C., Liyanage-Don, N., Rosner, G. F., Bernstein, E. J., Mohan, S., Beckley, A. A., … Wan, E. Y. (2021). Post acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nature Medicine, 27(4), 601–615. View

Davis, H. E., McCorkell, L., Vogel, J. M., & Topol, E. J. (2023). Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. In Nature Reviews Microbiology (Vol. 21, Issue 3, pp. 133–146). Nature Research. View

Sudre, C. H., Murray, B., Varsavsky, T., Graham, M. S., Penfold, R. S., Bowyer, R. C., Pujol, J. C., Klaser, K., Antonelli, M., Canas, L. S., Molteni, E., Modat, M., Jorge Cardoso, M., May, A., Ganesh, S., Davies, R., Nguyen, L. H., Drew, D. A., Astley, C. M., … Steves, C. J. (2021). Attributes and predictors of long COVID. Nature Medicine, 27(4), 626–631. View

Castanares-Zapatero, D., Chalon, P., Kohn, L., Dauvrin, M., Detollenaere, J., Maertens de Noordhout, C., Primus-de Jong, C., Cleemput, I., & Van den Heede, K. (2022). Pathophysiology and mechanism of long COVID: a comprehensive review. In Annals of Medicine (Vol. 54, Issue 1, pp. 1473–1487). Taylor and Francis Ltd. View

Al-Aly, Z., Bowe, B., & Xie, Y. (2022). Long COVID after breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nature Medicine, 28(7), 1461–1467. View

Raman, B., Bluemke, D. A., Lüscher, T. F., & Neubauer, S. (2022). Long COVID: Post-Acute sequelae of COVID-19 with a cardiovascular focus. In European Heart Journal (Vol. 43, Issue 11, pp. 1157–1172). Oxford University Press. View

Renaud-Charest, O., Lui, L. M. W., Eskander, S., Ceban, F., Ho, R., Di Vincenzo, J. D., Rosenblat, J. D., Lee, Y., Subramaniapillai, M., & McIntyre, R. S. (2021). Onset and frequency of depression in post-COVID-19 syndrome: A systematic review. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 144, 129–137. View

Katie Bach; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2022, August 24). New data shows long Covid is keeping as many as 4 million people out of work | Brookings. View

World Health Organization, (2021). World health statistics 2021: monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals. View

Thaweethai et al., (2023). Development of a Definition of Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Saha Cardiovascular Research Center Faculty Publications. 78. View

Manning, W.G. and Mullahy, J. (2001) Estimating Log Models: To Transform or Not to Transform? Journal of Health Economics, 20, 461-494. View

Heeringa, S.G., West, B.T., Heeringa, S.G., Berglund, P.A., & Berglund, P.A. (2017). Applied Survey Data Analysis (2nd ed.). Chapman and Hall/CRC. View

Fitzmaurice, G. M., (2012). Applied Longitudinal Analysis. Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics, 10, doi:10.1002/9781119513469 View

Singer, J. D., & Willett, J. B. (2003). Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis: Modeling Change and Event Occurrence. New York: Oxford University Press. View

McDougall, J., DeWit, D. J., Nichols, M., Miller, L., & Wright, F. V. (2016). Three-year trajectories of global perceived quality of life for youth with chronic health conditions. Quality of Life Research, 25(12), 3157–3171. View

Enders, C. K. (2010). Applied missing data analysis. The Guilford Press. View

Little, R.J. and Rubin, D.B. (2019). Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. Vol. 793, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken. View

Huang, L., Li, X., Gu, X., Zhang, H., Ren, L., Guo, L., Liu, M., Wang, Y., Cui, D., Wang, Y., Zhang, X., Shang, L., Zhong, J., Wang, X., Wang, J., & Cao, B. (2022). Health outcomes in people 2 years after surviving hospitalisation with COVID-19: a longitudinal cohort study. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 10(9), 863–876. View

Xie, Y., Xu, E., Bowe, B., & Al-Aly, Z. (2022). Long-term cardiovascular outcomes of COVID-19. Nature Medicine, 28(3), 583–590. View

Thompson, E. J., Williams, D. M., Walker, A. J., Mitchell, R. E., Niedzwiedz, C. L., Yang, T. C., Huggins, C. F., Kwong, A. S. F., Silverwood, R. J., Di Gessa, G., Bowyer, R. C. E., Northstone, K., Hou, B., Green, M. J., Dodgeon, B., Doores, K. J., Duncan, E. L., Williams, F. M. K., Walker, A. J., … Steves, C. J. (2022). Long COVID burden and risk factors in 10 UK longitudinal studies and electronic health records. Nature Communications, 13(1), 3528. View

Seeman, T. E., McEwen, B. S., Rowe, J. W., & Singer, B. H. (2001). Allostatic load as a marker of cumulative biological risk: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 98(8), 4770–4775. View

Pierce, M., Hope, H., Ford, T., Hatch, S., et al. (2020) Mental Health before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Longitudinal Probability Sample Survey of the UK Population. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7, 883-892. View

Bonanno, G. A., Westphal, M., & Mancini, A. D. (2011). Resilience to Loss and Potential Trauma. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 7(1), 511–535. View

Cutler, D. M. (2022). The Costs of Long COVID. JAMA Health Forum, 3(5), e221809. View