Journal of Social Work and Welfare Policy vol. 2 iss. 1 (2024), Article ID: JSWWP-115

https://doi.org/10.33790/jswwp1100115Research Article

The Interaction of Gender Identity and Sexual Assault on Campus

R. Lane Forsman, Ph.D., LCSW1*, and Jennifer Erwin, Ph.D., JD, MSW2

1*Assistant Professor, Department of Social Work, University of Northern Iowa, United States.

2Assistant Professor, Department of Social Work, Southern Illinois University – Edwardsville, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: R. Lane Forsman, Ph.D., LCSW, Department of Social Work, University of Northern Iowa, United States.

Received date: 15th February, 2024

Accepted date: 21st June, 2024

Published date: 24th June, 2024

Citation: Forsman, R. L., & Erwin, J., (2024). The Interaction of Gender Identity and Sexual Assault on Campus. J Soci Work Welf Policy, 2(1): 115.

Copyright: ©2024, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Introduction

Sexual violence is a continued and pervasive problem on college campuses. Among 18 – 24-year-old students cisgender females are 3 times more likely to experience sexual violence than other cohorts of females, cisgender males are 5 times more likely to experience sexual violence than members of their cohort who do not attend college, while ¼ of transgender students will experience sexual violence [1-3]. As such, colleges and universities have done a lot of work in recent years to improve the availability of, and access to, prevention and interventions services. However, aside from prevalence rates, there is still a large gap in understanding the needs and experiences of students other than the cisgender female in reference to sexual violence. This lack of understanding contributes to the differential knowledge and perceptions of campus sexual violence service centers by students on campus [4-5].

Experiences of Sexual Violence and Individual Outcomes

In the extant literature it has been identified that certain types of sexual violence predispose individuals to differential outcomes as compared to alternate forms of victimization. Griffin and Read [6] found that in female college students outcomes related to problem drinking, revictimization, and PTSD differed depending on whether the individual was coerced through violence or incapacitation. Non contact sexual harassment and contact related sexual violence may lead to differences in feelings of safety in the college environment [7]. Further, while variance in the specific type of sexual violence has not been found to have differential effects as of yet, experiencing sexual violence may lead to problems such as lower grade point average and dropping out of university [8].

Gender Identity and Sexual Victimization Outcomes

There is already some literature on how certain gender groups may differ in relation to sexual violence. For instance, cisgender adult males are less likely to seek help than their cisgender female peers [9] and may be more likely to experience feelings of aggression post assault [10]. However, research and formal services for cisgender males are focused primarily on prevention of violence against others leaving much knowledge missing for those who experience sexual violence. For non-cis individuals the available information is even less. Trans persons with a long-term partner pre-transition may be at increased risk for experiencing sexual IPV [11] and trans persons are much less likely to seek formal help than other groups, often waiting a minimum of 2 years if they do [12]. But this is a new line of research and there are still many unanswered questions. While there is a broad amount of research on LGBTQ+ youth as a cohort we contend that the monolithic approach to LGBTQ+ research continues to muddy the waters around the differences and intersectionalities related to sexual orientation and gender identity; as this project does not assess sexual orientation as a variable we chose to focus our attention on what is known about the trans population specifically. However, future research into the relation between gender identity and sexual orientation in this arena is merited and may be further supported by this study.

Responsibility of College Campuses

Considering the increased prevalence of sexual violence on college campuses, the lack of information in relation to the needs of cisgender male and transgender persons after sexual violence, and the amount of resources expended by colleges and universities in relation to sexual violence, it is important that college campuses and the multitude of social workers who provide direct care are prepared to respond to the needs of all of their students [13]. To address this concern this study sets out to examine how both experiences of sexual violence and outcomes after an assault may differ on college campuses by gender identity and type of sexual violence experience.

Research Questions and Hypotheses

This study is guided by four research questions focused on experiences of sexual victimization for cisgender adult men and transgender persons: (1) Is there a relation between gender identity and sexual victimization experience? (2) Is there a relation between type of sexual victimization experience and physical health, mental health, and academic success? (3) Is there a relation between gender identity and physical health, mental health, and academic success? (4) Is the relation between sexual victimization experience and physical health, mental health, and academic success moderated by gender identity?

The associated hypotheses for these research questions are: (1) There will be a relation between gender identity and sexual victimization experience. However, due to the exploratory nature of this question the nature of the relation is not hypothesized at this time. (2) Sexual victimization experiences that are more physically invasive (completed sexual penetration) or potentially prolonged (a sexually abusive romantic relationship) will predict more negative physical health, mental health, and academic success outcomes than other forms of sexual victimization. (3) Transgender students will have poorer physical health, mental health, and academic success outcomes. (4) The interaction of sexual victimization experience and gender identity will predict more negative physical health, mental health, and academic success outcomes for transgender students than for cisgender students.

Study Design

This study consists of a secondary data analysis of a national sample of colleges and universities participating in the American College Health Association’s (ACHA) National College Health Assessment (NCHA). The NCHA is a survey that colleges and universities administer in the fall and spring semester each year. Member institutions self-select participation each year and only those schools who solicit survey participation through random sampling of their student body are included in national data sets. The survey covers a wide variety of topics around student health; of particular interest to this study are questions relating to experiences of sexual victimization, gender identity, and measurement of physical health, mental health, and academic success. The data comes from a national convenience sample of ACHA member institutions over the course of three years of collection.

Survey

The NCHA-IIc is the third update to the NCHA Assessment and has been administered since Fall of 2015. Data retrieved for this study were restricted to collection years that used the IIc version, through Spring of 2018. The decision was made to restrict the data file to only those years utilizing the IIc because of changes in how gender identity is measured allowing for more robust data gathering and separating of participants into the necessary discreet identities for this study.

Sample

The ACHA does not provide recipients of their data with identifying information on the universities in the data set. The sample includes a mix of public and private institutions as well as small and large student bodies and Carnegie Classifications. Membership of the ACHA accounts for about 50% of students attending a college or university in the United States; however, not all member institutions select to participate in the NCHA each year. This makes the overall sample one of convenience based on institutional self-selection. For the survey administrations used in this study, 208 institutions of higher learning participated.

Despite the overall convenience sample of member institutions, the ACHA requires any schools whose data is included in national data sets to utilize one of two sampling methods for survey recruitment. They must either randomly sample their entire student body or randomly sample the classes/classrooms that will be used to administer the survey. Institutions are not required to utilize one of these sampling methods to participate in data collection, but if they do not, they are excluded from national data sets leaving the 208 in the final sample.

Exclusion and inclusion. Only those students who have experienced a sexual victimization, who have undergraduate student standing, and who fall within the gender categories of cisgender female, cisgender male, transgender female, and transgender male were included in analyses for the current study. Those students who have not experienced a sexual victimization, who are graduate or professional students, who did not identify their student standing, who do not fall within the gender identities of interest for the project, or who did not provide their gender identity were excluded. The current study included a sample of 27,411 students who classified as a cisgender woman, 4,500 classified as a cisgender man, 57 classified as a transgender woman, and 101 classified as a transgender man.

Data

Variables and measurement. The main variables of interest in this project are gender identity and sexual victimization experience. The remaining dependent variables in this project all relate to physical health, mental health, and academic success.

Main variables of interest. Gender identity is measured through three items. The first item asked respondents to identify their sex assigned at birth with available response options of “female” or “male.” The second item asked participants if they identify as transgender with available response options of “no” or “yes.” The final item asked participants to describe their gender identity and gave response options of “woman,” “man,” “trans woman,” “trans man,” “genderqueer,” and “another identity.” For use in analyses a new variable was created from the information in these three items. The analysis variable is coded as “cis woman,” “cis man,” “trans woman,” or “trans man.” Any respondent who selected “trans woman” or “trans man” in the original gender identity item will be coded as such. Further, individuals who selected that they identify as transgender and selected a binary gender identity of man or woman were included in appropriate trans samples for analysis.

Sexual victimization experience is measured through two items. The first item asked participants if in the last twelve months, “were you in a physical fight,” “were you physically assaulted (do not include sexual assault),” “were you verbally threatened,” “were you sexually touched without your consent,” “was sexual penetration attempted (vaginal, anal, oral) without your consent,” “were you sexually penetrated (vaginal, anal, oral) without your consent,” or “were you a victim of stalking.” The second item asked participants if they have been in an intimate relationship in the past twelve months that was, “emotionally abusive,” “physically abusive,” or “sexually abusive.” For this project a new variable was created to assess only sexual victimization. Responses will be coded as “sexual touching,” “attempted sexual penetration,” “completed sexual penetration,” “sexually abusive relationship,” and “multiple forms of victimization.”

Physical health. The first two variables addressing physical health have to do with sleep quality and fatigue. Respondents were asked, “on how many of the past 7 days did you get enough sleep so that you felt rested when you woke up in the morning?” Response options include, “0 days,” “1 day,” “2 days,” “3 days,” “4 days,” “5 days,” “6 days,” and “7 days.” They were also asked, “In the past 7 days, how much of a problem have you had with sleepiness (feeling sleepy, struggling to stay awake) during your daytime activities?” The response options include “not a problem at all,” “a little problem,” “more than a little problem,” “a big problem,” and “a very big problem,” with scores ranging from 0 – 4.

The next physical health variable measures substance use. Since chronic substance use and abuse can cause negative physical health outcomes, these behaviors are included here to track participants who are at increased risk for the negative physical health symptoms due to their substance use behaviors. Participants were asked to respond to 18 items rating how often within the last 30 days they had used both legal and illicit substances. Response options included “never used,” “have used, but not in the last 30 days,” “1-2 days,” “3-5 days,” “6-9 days,” 10-19 days,” “20-29 days”, and “used daily.” Two new variables were created from these items. One will sum the number of substances used in the last 30 days and the other will sum the total number of days of substance use.

Mental health. Mental health variables track self-report of mental health symptoms and behaviors and feelings associated with mental and emotional stability. The first variable assesses how safe students feel on campus and in the community. The variable asks respondents, “how safe do you feel: on this campus (daytime)? On this campus (nighttime)? In the community surrounding this school (daytime)?” And “in the community surrounding this school (nighttime)?” For each of the four options they were asked to select between “not safe at all,” “somewhat unsafe,” “somewhat safe,” and “very safe.” For use in the analyses the four variables were recoded as 0 – 3 and summed to create a single continuous variable with a range of 0 – 12 with lower scores indicating feeling less safe.

The next variable assessing mental health asks students if they have ever experienced any of 11 common mental health symptoms related to depression, anxiety, and self-harm. Respondents were asked to select from the options, “no. never,” “no, not in the last 12 months,” “yes in the last 2 weeks,” “yes in the last 30 days,” or “yes, in the last 12 months.” One variable was created from these responses. The variable summed the number of items the student selected as happening, excluding those symptoms that have not been experienced in the last 12 months. This provided a possible score ranging from 0 – 11.

Academic success. Academic success is being assessed through two avenues. One is self-report of grade point average, and the other is through direct questioning of students about their perceptions of impediments to academic performance. First, students were asked to report their “approximate cumulative grade average” using the options “A,” “B,” “C,” “D/F,” and “N/A.” The variable was recoded to indicate the N/A response as missing data and so that higher scores on the new 0 – 3 scale indicate higher grade averages.

The other set of items asks students to rate “within the past 12 months, have any of the following affected your academic performance?” Nine items related to the experience of sexual violence were selected. Two variables were created from these items. The first summed the number of issues from the list that students perceive have affected their academic performance for a score ranging from 0 – 9. The second variable used the original item related to assault (sexual) and the available response options of, “this did not happen to me/not applicable,” “I have experienced this issue but my academics have not been affected,” “received a lower grade on an exam or important project,” “received a lower grade in the course,” “received an incomplete or dropped the course,” and “significant disruption in thesis, dissertation, or practicum work.” Options were recoded as 0 – 5, with higher scores indicating a greater disruption in academic performance.

Analytic Strategy

All statistical analyses in this study were completed using SPSS version 24. Question one was analyzed using a chi square test of independence and companion post hoc tests. Questions two through four were analyzed through three separate multivariate analysis of covariance models (MANCOVA); one model was used for each separate outcome domain between physical health, mental health, and academic success.

Results

Research Question 1

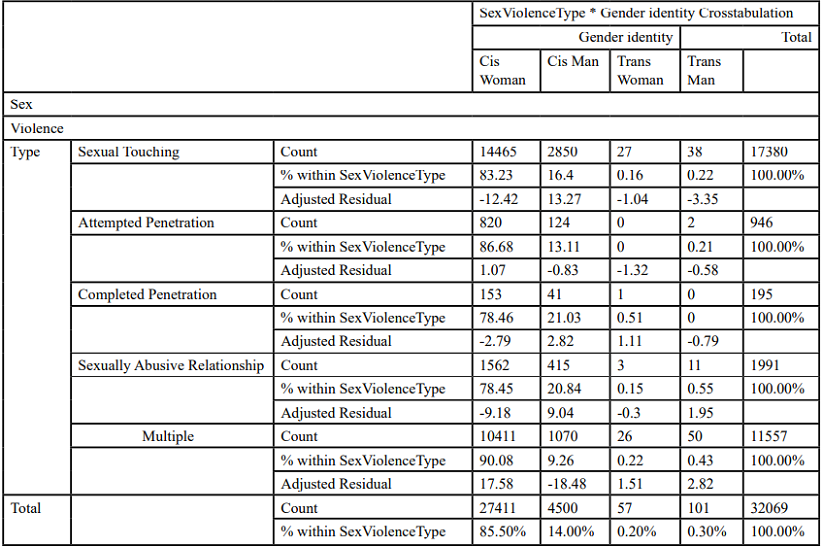

Results for the initial chi square model can be found in Table 1. A statistically significant relationship between gender identity and sexual violence experience was identified (x2(12) = 401.62, p < .001) with a medium effect size based on the degrees of freedom (Cramer’s V = 0.11). To assess for statistical significance within the cells of the chi square model, the adjusted residuals were used in bivariate chi square tests of significance.

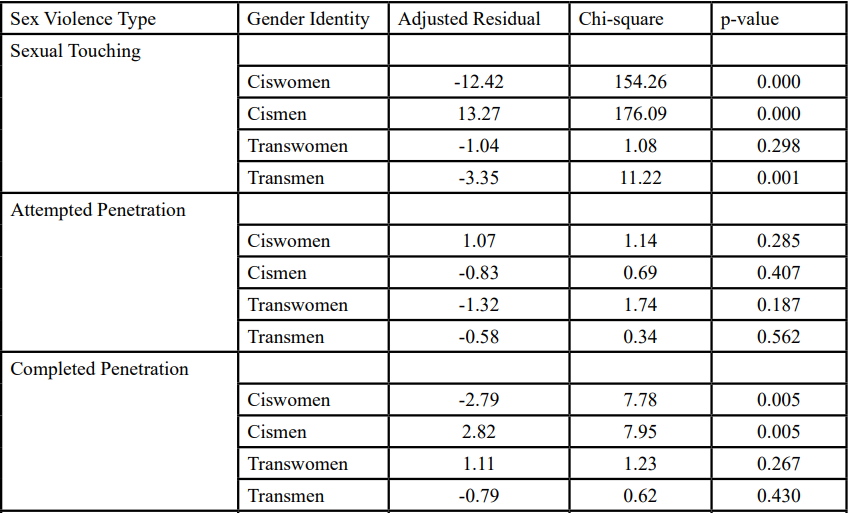

Results for the post hoc analysis can be found in Table 2. Due to the number of analyses being performed a Bonferroni correction was applied providing a final alpha level of 0.003. Based on this cutoff value statistically significant relations were found between the cisgender female identity and sexual touching (p < .001), sexually abusive relationships (p < .001), and multiple forms of sexual violence (p < .001); cisgender male identity and sexual touching (p < .001), sexually abusive relationships (p < .001), and multiple forms of sexual violence (p < .001); and transgender male identity and sexual touching (p < .001).

To further assess for the practical significance of these relationships, 2x2 contingency tables were used to generate odds ratios using the statistically significant cells within the chi square analysis. Results for these analyses can be found in Table 3. Comparisons were done for the following groups: cismen and ciswomen by sexual touching; transmen and ciswomen by sexual touching; transmen and cismen by sexual touching; cismen and ciswomen by sexually abusive relationships; and cismen and ciswomen by multiple forms of sexual violence.

For comparisons of cisgender men and cisgender women, cisgender men were 1.30 times more likely to experience unwanted sexual touching and 1.80 times more likely to experience multiple forms of sexual violence. The remaining odds ratios were not statistically significant.

Research Questions 2 and 3

Due to the statistically significant interaction between gender identity and sexual violence experience in the MANCOVA model direct interpretation of statistically significant results for gender identity and sexual violence experience on the selected outcome variables will not be discussed. However, exploration of the estimated marginal means, in consideration with 95% confidence intervals, provides some useful observations from the data. Only those observations with independently interpretable confidence intervals will be discussed.

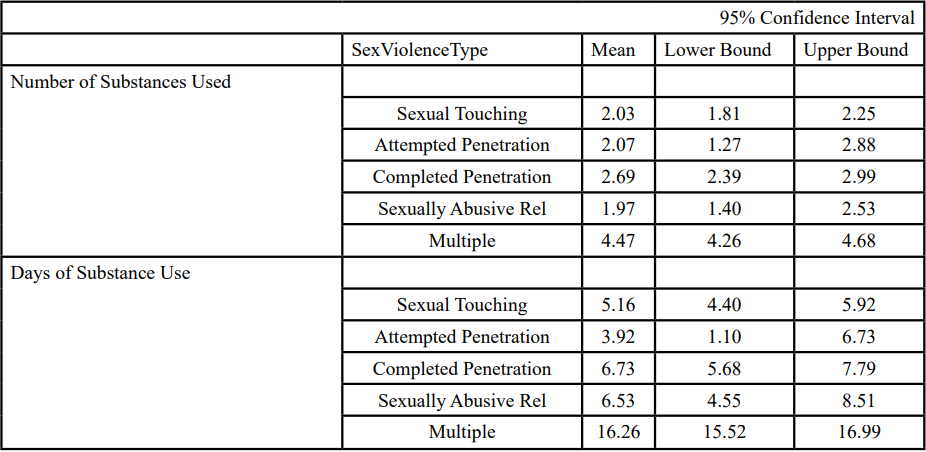

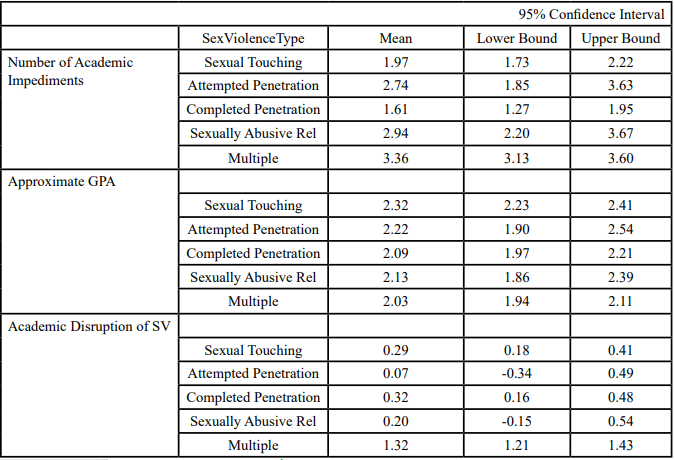

Research question two. Estimated marginal means and confidenceintervals can be found in Table 4. Starting off by examining the relation between type of sexual violence and physical health, the estimated marginal means suggest that in relation to substance use or misuse, experiences of multiple forms of sexual violence led to worse outcomes. Individuals who experienced multiple forms of sexual violence reported using almost double the number of substances (M = 4.47, 95% CI: 4.26, 4.68) as compared to the next closest group of completed penetration (M = 2.69, 95% CI: 2.39, 2.99). They also reported more than double the number of days of substance use in a month (M = 16.26, 95% CI: 15.52, 16.99) as compared to the next closest group of completed penetration (M = 6.73, 95% CI: 5.68, 7.79). Individuals who experienced multiple forms of sexual violence reported the ability to succeed academically as impeded at over four times the level (M = 1.32, 95% CI: 1.21, 1.43) of the next closest group of completed penetration (M = 0.32, 95% CI: 0.16, 0.48). Results can be seen in Table 5.

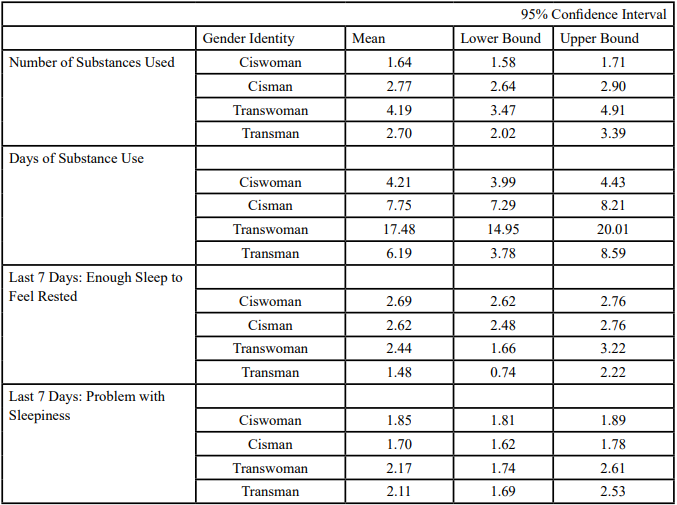

Research question three. Estimated marginal means and confidence intervals can be found in Table 6. Again, starting with the relation between gender identity and physical health outcomes, transwomen reported a greater number of substances used (M = 4.19, 95% CI: 3.47, 4.91) than all other groups. The next closest group was cismen (M = 2.77, 95% CI: 2.64, 2.90). Transwomen also reported using substances more often (M = 17.48, 95% CI: 14.95, 20.01) at over twice the rate of the next closest group, cismen (M = 7.75, 95% CI: 7.29, 8.21).

When assessing the number of mental health symptoms experienced, transgender persons report higher rates of mental health symptomology with transwomen reporting the highest levels (M = 8.40, 95% CI: 7.37, 9.43) followed by transmen (M = 7.92, 95% CI: 6.94, 8.89). This is in comparison to cisgender persons where ciswomen report higher rates of symptomology (M = 6.59, 95% CI: 6.49, 6.68) followed by cismen (M = 5.82, 95% CI: 5.63, 6.00).

When assessing the number of academic impediments post assault, the divide seems to be between transgender students and cisgender students with little variation within these groups. Transwomen report the highest number of impediments to success (M = 3.62, 95% CI: 2.68, 4.57) followed closely by transmen (M = 3.56, 95% CI: 2.79, 4.33). By comparison cisgender students report lower rates of impediment with cismen reporting the highest rate (M = 1.97, 95% CI: 1.82, 2.11) followed by ciswomen (M = 1.91, 95% CI: 1.84, 1.98). Finally, the report of the effect sexual violence specifically on the ability to succeed academically follows previous trends of appearing to be worse for transwomen (M = 0.94, 95% CI: 0.49, 1.38) with little variation among other groups and the next closest group being transmen (M = 0.47, 95% CI: 0.11, 0.83).

Research Question 4

Finally, the interaction was statistically significant across all three models with the outcome variables of number of substances used (p < .001), days of substance use (p < .001), sleep quality (p = .002), experiences of sleepiness (p < .001), feelings of safety (p < .001), number of mental health symptoms (p < .001), number of impediments to academic success experienced (p = .001), average GPA (p = .002), and the specific effect of sexual violence on academic success (p < .001) having p-values below alpha.

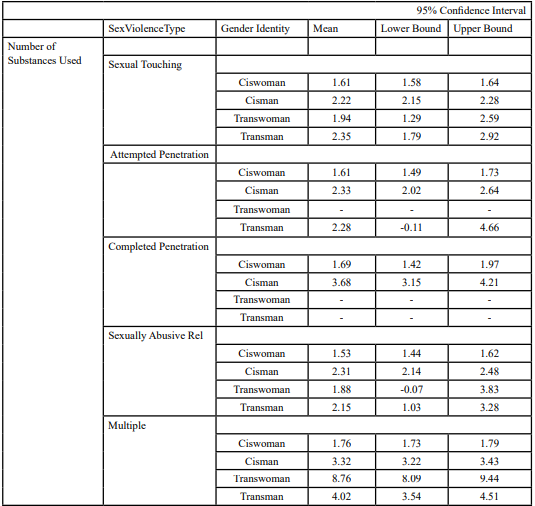

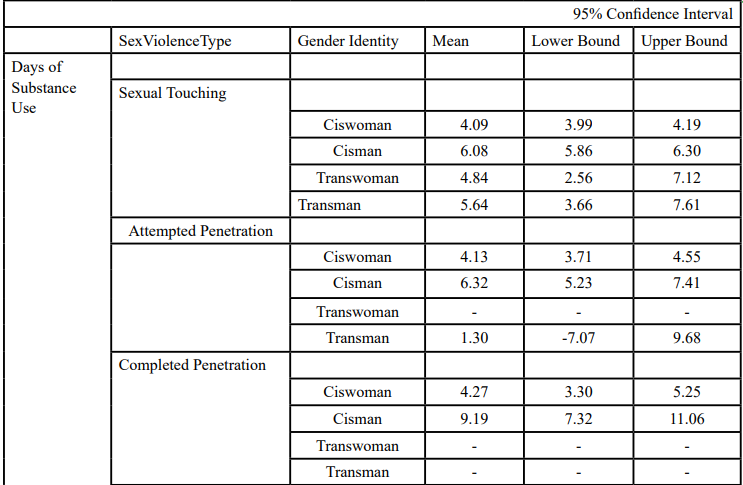

When comparing the estimated marginal means and confidence intervals by gender identity and experience of sexual violence three of the outcomes suggest that transwomen may be the most susceptible to negative outcomes in relation to sexual assault and that experiencing multiple forms of sexual violence may be the most damaging to academic success. A table for number of substances used can be found in Table 7, days of substance use can be found in Table 8, and the academic performance disruption of sexual violence can be found in Table 8. When breaking out the effects of these tables, data suggest that as compared to other members of their same gender identity who have had an experience of sexual violence transwomen who have experienced multiple forms of sexual violence (M = 8.76, CI: 8.09, 9.44) along with cismen who have experienced multiple forms of sexual violence (M = 3.32, CI: 3.22, 3.43) as well as completed penetration (M = 3.68, CI: 3.15, 4.21) may use the highest number of substances.

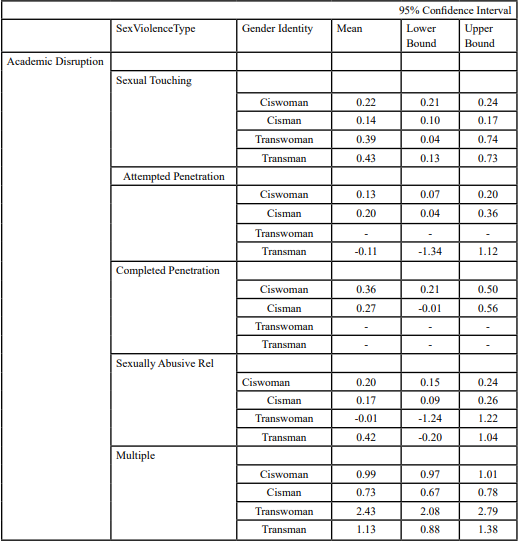

While transwomen who have experienced multiple forms of sexual violence use substances most often (M = 28.92, CI: 26.55, 31.29) as compared to all other groups. Finally, as compared to other members of their gender identity, ciswomen (M = 0.99, CI: 0.97, 1.01), cismen (M = 0.73, CI: 0.67, 0.78), and transwomen (M = 2.43, CI: 2.06, 2.79) who have experienced multiple forms of sexual violence may be at differential risk for experiencing academic disruption in relation to sexual violence with the greatest burden falling on transwomen.

Discussion

Limitations

While we are confident that the information in this study is useful in informing future work it is important to note its limitations. The collection method of the data means that this study is correlational in nature. We can see trends of things happening together, but we cannot be sure of causation. Another large limitation is the final sample size for trans participants. The subsample of trans participants is extremely low, so while the results encourage replication, they should be interpreted with care. Discussion of results should not be used to inform best practices yet, rather to guide future research.

Sexual Violence Experiences

When looking at the experiences of those students who have been subjected to sexual violence, several key takeaways emerge from the data. Acts of unwanted sexual touching, being in an abusive relationship, and experiencing multiple forms of sexual violence all have a statistically significant relation to gender identity. However, because this study is exploratory and we are limited by the study design, we are unable to demonstrate a causal relationship between gender identity and the experience of sexual violence. Using cisgender women as the comparison group, it appears that cisgender men are more likely to experience unwanted sexual touching and multiple forms of sexual violence when on college campuses; this adds to the existing literature that notes cis college men are more likely to have multiple attackers when experiencing victimization [10].

If confirmed by future studies this information may be important when developing prevention programs. It could help providers better utilize their resources by targeting specific groups with education about specific kinds of violence. Interventionists may be better prepared to respond to the needs of a survivor; if a practitioner knows that while cisgender men are less susceptible to experiencing sexual violence but when they do, they are less likely to have been in an abusive relationship and more likely to experience multiple forms of sexual violence than the cisgender female survivor it can help that practitioner be more prepared to respond to the trauma of the survivor in front of them. If all gender identities do not have the same experience of sexual violence, then sexual violence services should be tailored for individual identities.

Outcomes Post Assault

Physical health. When examining the effects of sexual violence on physical health outcomes, the analyses suggest that experiencing multiple forms of sexual violence may have the strongest impact on physical health. Individuals who experienced multiple forms of sexual violence are at increased risk for rates of substance use that are twice as high or higher than other student survivors of sexual violence, which can have both short- and long-term consequences for physical health. These preliminary findings offer a good jumping off point for future research.

This information on substance use rates is doubly important for service providers when someone reports experiencing sexual violence. For mental and behavioral health professionals, it is important to understand that self-medication of trauma through the use of substances is common among individuals who experience sexual violence, but that certain groups of people may be at higher risk for substance use concerns after an experience of sexual violence. For both mental health and physical health providers, it is important to have this information to be able to accurately assess for substance use concerns, to educate the individual on the realities of substance misuse, and to be careful when prescribing medication as interactions between prescribed and nonprescribed substances can have dangerous, and possibly fatal, side effects.

Mental health. When assessing how a particular type of sexual violence experience and gender identity play into outcomes, there does not appear to be much differential effect on mental health. However, individuals reported experiencing anywhere from 6 – 8 mental health symptoms out of a possible 11. This underscores the idea that service providers in the sexual violence field should treat all individuals who seek help as having been through a traumatic experience and not downplay the lived experience or how it may affect the individual regardless of the specifics of their victimization or their identity. Sexual violence, regardless of type, is mentally harmful to all who experience it.

Academic success. This study is focused on experiences of a college cohort of sexual violence survivors. One of the key factors of their experience is their ability to maintain academic success and continue their chosen educational path despite experiencing sexual trauma. When considering GPA in the context of being subjected to sexual violence there does not appear to be much variation by gender identity. However, GPAs for those students who experience sexual violence are across the board rather low with scores at or below the retention line for most universities. This supports previous work in the area indicating that an experience of sexual violence can be a direct impediment to academic success [3,14]. Students who fail to finish an undergraduate degree are at a disadvantage in relation to future financial earnings, and those who have taken out student loans and fail to finish their degree are at increased risk for defaulting on their loans [15].

When looking further into academic success and sexual violence, those individuals who have experienced multiple forms of sexual violence report greater difficulty in remaining successful. This is important for providers to know as cisgender men on campus may be at greater risk for being subjected to multiple forms of sexual violence increasing their chances of experiencing an academic disruption. Being aware of these differences in risk can help campuses better support their students in remaining in school and successfully completing their education after an experience of sexual violence.

Implications for Social Work Practice

Social workers are frequently the front-line employees providing sexual violence related services on college campuses and as such we bring our professional perspective to the table [13]. Further, younger generations are more likely to identify as LGBTQIA+ than older generations and a growing body of research indicates that LGBTQIA+ people continue to experience high rates of sexual violence especially when compared to their cisgender and heterosexual peers across demographic cohorts [1-3]. To help address this disparity, social workers can address stigmatization and discrimination at the community level by confronting the notions of traditional gender roles, developing policies to address transphobic and homophobic language, and implementing programming to help students identify microaggressions, hate speech, and learn how to respond to it.

Additionally, interventions have traditionally focused on heterosexual cisgender females, however results of this study suggest that cisgender males are more likely than cisgender females to experience unwanted sexual touching and multiple forms of sexual violence. This finding indicates a need for any campus-wide programming that is meant to address sexual violence to be inclusive of the fact that cisgender males have differential experiences of sexual violence. Social workers should undergo training to ensure that they are not perpetuating traditional gender norms and stereotypes that might decrease the likelihood of cismen seeking services after experiencing sexual violence and as previously stated, existing research has indicated that many trans people never report their experiences of sexual victimization and when they do they may wait at least 2 years before doing so. As such, protocols around reporting instances of sexual violence should be inclusive (e.g., gender-affirming forms) and those who have initial contact with victims need to avoid assumptions related to the gender and sexuality of either the victim or perpetrator(s) while using proper names and pronouns when talking to the individual and in any documentation or records.

Social workers providing services to those who have experienced sexual violence must be aware of the differential experiences that people have based on a variety of factors, including gender identity and type of sexual violence. Social workers need to make sure that the interventions they are using can be tailored to each subgroup so that they are effective. For example, transgender students in this study reported having more mental health symptoms than cisgender students. Often, experiencing symptoms can lead people to increase their substance use, and this study also found that transwomen reported using more substances and using substances more frequently than cisgender students. Should this finding bear out in future research a social worker would need to be prepared to address both substance use and mental health symptoms, with the knowledge that transgender students are more likely to be dealing with these issues after experiencing sexual violence. In this study, transwomen were more susceptible to negative outcomes than any other group and, while the findings are only exploratory due to sampling issues, social workers working with transgender students need to be conscious of the role that gender identity takes in experiences of, outcomes post, and help seeking decisions for sexual violence.

Conclusion

Much work has been done to assess sexual violence on college campuses, particularly around reducing the number of occurrences, but the extant literature lacks a solid understanding of how gender influences the experiences and outcomes of the violence. This study suggests a relationship exists between gender identity, experiences of sexual violence, and post-assault outcomes. Continued work should be done to tease out the interaction of gender identity in these spaces by replicating this work and expanding the work to include more identities on the gender spectrum. Additionally, due to limitations in sample size and study design, this study is unable to demonstrate causation, but future research can be conducted to determine if a causal relationship exists. Until we can eliminate sexual violence, we need to be ensuring that the work being done is inclusive of all those who may be victimized.

Conflict of interest:

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Black et al., (2011). National Sexual Assault Conference.View

Sinozich, S., & Langton, L. (2014). Rape and sexual assault victimization among college-age females, 1995-2013. US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics.View

Cantor, D., Fisher, W. B., Chibnall, S., Townsend, R., Lee, H., Bruce, C., & Thomas, G. (2015). Report on the AAU campus climate survey on sexual assault and sexual misconduct. Retrieved from www.aau.edu/uploadedFiles/AAU_ Publications/AAU_Reports/Sexual_Assault_Capus_Survey/ AAU_Campus_Climate_Survey_12_14_15.pdfView

Walsh, W. A., Banyard, V. L., Moynihan, M. M., Ward, S., & Cohn, E. S. (2010). Disclosure and service use on a college campus after an unwanted sexual experience. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 11(2), 134-151.View

Franklin, C. A., Menaker, T. A., & Jin, H. R. (2019). University and community resources for sexual assault survivors: familiarity with and use of services among college students. Journal of school violence, 18(1), 1-20.View

Griffin, M. J., & Read, J. P. (2012). Prospective effects of method of coercion in sexual victimization across the first college year. Journal of interpersonal violence, 27(12), 2503-2524.View

Pinchevsky, G. M., Magnuson, A. B., Augustyn, M. B., & Rennison, C. M. (2020). Sexual victimization and sexual harassment among college students: A comparative analysis. Journal of family violence, 35, 603-618.View

Molstad, T. D., Weinhardt, J. M., & Jones, R. (2023). Sexual assault as a contributor to academic outcomes in university: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 24(1), 218-230.View

Light, D., & Monk-Turner, E., (2009).Circumstances surrounding male sexual assault and rape: findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. J Interpers Violence. 24(11):1849-58.View

McLean, I. A. (2013). The male victim of sexual assault. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 27(1), 39-46.View

Hester, M., Williamson, E., Regan, L., Coulter, M., Chantler, K., Gangoli, G., ... & Green, L. (2012). Exploring the service and support needs of male, lesbian, gay, bi-sexual and transgendered and black and other minority ethnic victims of domestic and sexual violence. Bristol: University of Bristol.View

Marine, S. B. (2017). For Brandon, for justice. Intersections of identity and sexual violence on campus, 83.View

Bennett, E. R., Snyder, S., Cusano, J., McMahon, S., Zijdel, M., Camerer, K., & Howley, C. (2021). Supporting survivors of campus dating and sexual violence during COVID-19: A social work perspective. Social work in health care, 60(1), 106-116.View

Jordan, C. E., Combs, J. L., & Smith, G. T. (2014). An exploration of sexual victimization and academic performance among college women. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 15(3), 191 200.View

United States Department of Education. (2015). Fact Sheet: Focusing higher education on student success. View