Journal of Social Work and Welfare Policy vol. 2 iss. 1 (2024), Article ID: JSWWP-116

https://doi.org/10.33790/jswwp1100116Research Article

Daca Recipients During a Pandemic: Mixed Method Study of DACA Recipients who Worked as Essential Workers During the Covid-19 Pandemic

Nicole Dubus

Associate Professor, School of Social Work, San Jose State University, San Jose, California, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Nicole Dubus, Associate Professor, School of Social Work, San Jose State University, San Jose, California, United States.

Received date: 15th May, 2024

Accepted date: 01st July, 2024

Published date: 03rd July, 2024

Citation: Dubus, N., (2024). Daca Recipients During a Pandemic: Mixed Method Study of DACA Recipients who Worked as Essential Workers During the Covid-19 Pandemic. J Soci Work Welf Policy, 2(2): 116.

Copyright: ©2024, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Abstract

Background: This paper highlights the experiences of undocumented immigrants who are participants in the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA). The United States has implemented several policies to address immigration issues, focusing on undocumented immigrants. DACA provides a two-year reprieve from deportation for a select group brought to the U.S. as children before they were 16 years old and have lived continuously in the U.S. since 2007. Nearly half of the 1.2 million DACA-eligible immigrants are essential workers. During the Covid-19 pandemic, essential workers were on the frontlines of exposure. This study examines the emotional experiences of DACA recipients who worked as essential workers during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Methods: This study involved 60 DACA recipients. An anonymous survey was available to self-identified DACA recipients, with 60 completing the survey and 12 participants from the survey agreeing to individual interviews. Data was examined using content analysis to capture DACA recipients’ experiences. The ecological theory was used to understand the influence of various systems on the experiences of the participants.

Results: The 60 DACA-recipient participants survey responses and the 12 individual interviews from the survey participants revealed that their immigration status significantly impacted their lives, causing anxiety and depression. The data shows a layered experience of living with DACA during the Covid-19 pandemic years.

Keywords: Covid-19, Forced Migrants, DACA, Essential Workers, Pandemic, Health Inequity

Introduction

The Intersection of COVID-19 and DACA Recipients: Challenges, Contributions, and Implications

The confluence of the COVID-19 pandemic and the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program has generated significant scholarly interest. This section aims to synthesize key findings and research questions related to this critical intersection.

The following reflects recent findings from the Center for American Progress analysis in 2020 [1] on the impact of COVID-19 on DACA recipients and some factors that increased the burden on such recipients. The pandemic has disproportionately affected vulnerable populations, including DACA recipients. Research has explored their health outcomes, economic stability, and access to healthcare. Understanding the pandemic’s differential impact on this group is crucial for informed policy decisions.

DACA is a program meant to correct an inhumane condition created as an unintentional consequence of immigration policies [2]. The following provides the backdrop to understand the economic and social contributions of DACA Recipients. The Center for American Progress [1] analysis highlights the demographic and economic impacts of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) recipients in the United States. Their key national findings show that on average, DACA recipients arrived in the U.S. at age 7, and more than one-third arrived before age 5. The average DACA recipient is now 32 years old, having waited years for Congress to address their situation. 254,000 U.S.-born children have at least one parent who is a DACA beneficiary. DACA recipients and their households pay $5.6 billion in federal taxes annually. After taxes, they have a combined $24 billion in spending power. The key state-level findings from the analysis showed that DACA recipients contribute significantly, paying $3.1 billion in state and local taxes each year. In 42 states and Washington, D.C., they pay over $1 million in taxes annually, with higher contributions in a dozen states. Despite their contributions, efforts to rescind DACA are concerning, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic when many recipients are on the frontlines [1].

Insecure legal status like DACA impact the person’s risks. The Center for American Progress analysis [1] examined healthcare access during the beginning of the pandemic for DACA recipients and their families. According to the CAP analysis [1], barriers to COVID-19 testing, treatment, and vaccination were a concern for DACA recipients. Their immigration status intersects with healthcare eligibility, affecting their ability to seek timely medical assistance during the crisis. In addition, their insecure status impacts their mental health and resilience. Living through both DACA uncertainty and the pandemic has implications for mental health, and researchers have investigated coping mechanisms, stressors, and resilience strategies among this population. Even with these challenges, DACA recipients continue to contribute economically. The CAP report posited that their work authorization had implications for employment outcomes during the pandemic, emphasizing their essential roles in various sectors.

The CAP analysis [1] concluded that even with evidence of DACA’s effectiveness in correcting immigration problems, and the evidence of DACA recipients’ contributions to the US economy, legal battles over DACA have intensified during the pandemic [1,3]. Understanding the impact of legal uncertainty on recipients’ well being and advocating for pathways to citizenship are critical research areas. This present study seeks to better understand the DACA recipient’s experience to inform policy changes. This is a complex situation that affects individuals, communities, states, and the nation. The implications are far reaching for each stakeholder and touch the economy, education, healthcare access and delivery, communities, and present and future immigration policies [2]. This study seeks to move this discussion and understanding deeper by hearing the voices of those caught in this critical intersection of DACA and Covid, and in more general terms, how we as a nation understand and manage healthcare delivery to our most vulnerable communities.

In conclusion, rigorous research on COVID-19 and DACA recipients informs evidence-based policies, underscores their resilience, and highlights the urgent need for stability and protection during these unprecedented times [4]. To establish helpful policies, a deeper understanding of the self-perceived experiences of DACA recipients during the pandemic is needed.

This paper seeks to understand the self-perceived experiences and challenges of DACA recipients who worked in essential jobs during the Covid-10 Pandemic. The data was collected during the pandemic which brings an immediate and personal voice to this topic. The findings from this study are based on the responses from 60 DACA recipients who completed a survey that consisted of multiple choice and short essay answers. Participants of the survey were invited to a one-to-one interview via a video conferencing platform (Zoom). Twelve participants accepted the invitation to an individual interview. The final sample consisted of 60 survey participants, and from those participants, 12 individual interview participants.

Over 1.3 million people in the United States are eligible for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) [5]. Nearly half a million DACA recipients are in California, with 10,000 attending a California State University [6]. DACA was developed to address the needs of children brought to the U.S. when they were young [2]. It is not a path to citizenship and does not protect family members who are undocumented but not eligible for DACA. DACA recipients experience increased anxiety and depression compared to permanent residents. Pre-pandemic, over a third of Latino youth (the majority of DACA recipients) seriously considered suicide [7]. One study reviewed the health concerns of DACA-eligible Latinos aged between 18-and 31 and found that mental health was their primary concern [8].

Although the students viewed DACA as beneficial in promoting belonging, peer support, and increased access to opportunities, this status also presents unanticipated challenges [4]. Individuals with insecure legal status are more susceptible to stress-related disorders due to long-term discrimination and marginalization known to harm mental health [7]. Challenges include a new precarious identity and greater adult responsibilities such as financial and familial obligations [8]. Many immigrant youths are driven by familial obligations including their desire to help their family financially [20]. This need comes from acknowledging that their parents left their home countries for a better living in the U.S., and it is their way of paying back their parents for their sacrifices [9]. Key findings from a report by the Institute of Taxation and Economic Policy completed in March of 2017 found that 11 million DACA-eligible immigrants who live and work in the US contribute more than $11.74 billion in state and local taxes with projected ten-year tax revenue of $103 Billion [10].

DACA provides recipients with permission to work and attend higher education [2]. A third of recipients work and attend higher education because they have family members who are unable to work due to their immigration status [11]. This places more responsibility on the DACA family member to work [12]. Luna and Montoya [12] specifically noted that “family” was the most valuable form of social capital from the DACA applicant's standpoint. DACA provided the leverage required to maximize family capital by providing students with employment and the opportunity to pursue higher education. Their motives are much more complex and are often underlined with dreams of resilience for their families and communities, which can overburden the DACA recipient [13].

The DACA program was a temporary policy until a comprehensive immigration policy is enacted [2]. The DACA recipients and their families fear the end of the policy, family members’ possible deportation, and the stigma associated with "illegal" status [4]. These fears have increased depression and suicidal thoughts among DACA recipients [8]. Despite being more susceptible to stress-related disorders due to long-term discrimination and marginalization which are known to harm mental health [7], discrimination causes depression, anxiety, physical illness, and psychological distress [14]. Access to culturally competent mental health services for DACA recipients is important. Mental health professionals who have knowledge of DACA and/or work with immigrant communities can address the unique situation that DACA recipients experience separate from family and friends [15]. Literature on migration trauma-informed practice indicates individuals who have experienced primary and secondary migration stressors are at increased risk for symptoms of PTSD, depression, anxiety, and severe mental illness [15,16].

DACA during COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated stress and hardships for migrant families. These families are more likely to reside in multigenerational households and work in crowded environments with inadequate ventilation [17]. Interestingly, during the pandemic, many of these workers were considered essential, playing a crucial role in keeping the nation functioning. Sectors such as meatpacking, produce production, grocery stores, factories, and healthcare heavily rely on DACA recipients and others with insecure immigration status [18].

Despite working in unsafe conditions, DACA recipients living in multigenerational homes faced the challenge of supporting their families while also protecting them. Often acting as liaisons for their undocumented family members (many of whom were parents and grandparents at high risk for COVID-19 complications), they navigated the healthcare system [19]. However, finding health information in their primary language (Spanish) was difficult, especially regarding precautionary measures like masking mandates and social distancing [18]. Kusters and colleagues [20] analyzed health department websites from 10 of the largest U.S. cities and found that, while there was great effort to provide information to various communities, Spanish language information was inadequate or missing. When the information was in Spanish, it may not have culturally-effective and accessible language, cultural contexts, and variety of formats that would enable Spanish speaking communities to understand and feel secure in the information [20]. Likewise, lack of information in other languages hindered communication with other immigrant communities [21].

Additionally, forced migrants may distrust governments and fear seeking services due to the risk of discovery and deportation [22,23]. Several factors contribute to the risk of contracting COVID-19, including old age, obesity, male sex, and diabetes [23]. Diabetes affects 22% of the Latino population, making Latinos vulnerable even if they have secure immigration status [23].

Theory

The ecological theory was used to understand the influence of various systems on the experiences of the participants [24]. This core social work theory posits that humans are influenced by biology, psychology, social institutions, culture, and structures of power and privilege. As we are influenced by these spheres, we also influence them and the lives around us. It is a dynamic process that involves the person's stage in life (life course perspective) and the times in which they live. The ecological theory provides the concepts needed to understand human behavior within the social environment [24].

This theory is helpful in analyzing the data because it provides a framework to deepen our understanding of the complexity of the experiences described by the participants. By using the ecological theory, the data can be analyzed considering the biological factors that impact DACA recipient participants. Given that a major objective of the study was to understand the impact of Covid-19 on DACA individuals, using a theory that addresses biological factors is both appropriate and helpful. The theory suggests that as we grow, we are influenced not only by our biology and psychological makeup but also by societal structures, systemic oppression, and cultural identity [25]. Depending on one’s stage in human development, these forces and structures shape who we are and how we respond to disruptions in our environment, thereby suggesting effective interventions.

Studies examining childhood development, resilience, and environmental influences on human development have used the ecological theory to obtain multi-systemic perspectives [26-28]. The ecological theory’s multi-system, person-in-environment approach aids our understanding of the participants’ experiences during the Covid-19 pandemic, illustrating how one phenomenon (Covid-19) can reverberate through the bio-psycho-social-cultural aspects of a person.

Methods

This study explores the experiences of 60 DACA recipients. The findings from this study are based on the responses from 60 DACA recipients who completed a survey that consisted of multiple choice and short essay answers. Participants of the survey were invited to a one-to-one interview via a video conferencing platform (Zoom). Twelve participants accepted the invitation to an individual interview. Each participant of the 12 were interviewed individually, via Zoom in a confidential setting, most often in the office of the principal investigator and the home of the participant. Each interview lasted under an hour and was recorded with participant permission for later transcription and analysis. Descriptive and frequency statistics were applied to the 60 survey responses. For interviews, Content Analysis [29] was used.

Participants

Community partners and agencies supporting undocumented individuals and families disseminated flyers with a web address to an anonymous survey. Additionally, a QR code allowed participants to access the survey via their cell phones. The survey was online, consisting of 20 questions. The questions were a combination of multiple choice and short essays regarding their DACA status and the benefits and difficulties of their DACA status. Questions focused on the participant’s housing, household makeup, work and school experiences, and impact of DACA on their relationships and identity. A final question provided a contact number that the participant could call if they were willing to be interviewed confidentially. Those willing to meet were interviewed via Zoom video conferencing with the investigator and participant in separate and confidential settings, usually the office of the investigator and the home of the participant. The sample consisted of 60 participants providing 60 completed surveys and 12 individual interviews.

Data Collection

The study was conducted virtually. An anonymous survey link was shared on bulletin boards, university social media platforms, and regional Reddit threads using keywords related to DACA, undocumented status, and migration. Key informants could choose video or telephone interviews, with all interviewees opting for video. These semi-structured interviews featured open-ended questions, lasted just under an hour and were recorded and transcribed for analysis.

Data Analysis

The survey data was analyzed using statistical analysis, and the 12 transcribed interviews were analyzed using content analysis to delve into the lived experiences of DACA recipients and identify contributing factors. In-vivo codes were generated from interview transcripts, capturing participants’ experiences in their own words. These codes were then grouped into larger categories to reveal overarching themes—the narrative of participants’ experiences. The short essay survey responses were re-read and compared to the individual interviews data. This review looked for discrepancies or contradictions with the interview data. None were noted. Survey short essay responses that were also reflected in the interview data were coded similarly as the interviews. Content analysis was conducted by the principal investigator and three graduate students. Each investigator read the transcripts, created codes based on in vivo quotes, grouped the codes to organize the experiences, and combined similar concepts into categories as appropriate for clarity and commonalities. These categories were further discussed as a team until there was agreement on the coding, categories, and eventually the themes. The themes were explored until the main themes emerged. The key statistical findings of the survey are presented in the findings section through graphs. The main themes of the 12 interviews are presented in the findings section with in vivo quotes and summaries.

Human Subject Protection

Institutional approval was obtained, and participants were informed of their rights. Survey respondents accessed an anonymous URL link, and no identifying information was collected. Survey respondents were given a contact number to call to express their interest in being interviewed. Interviewees received detailed information about the process and their rights. Interviews were conducted via confidential Zoom links, recorded with consent, and transcribed without identifying details. All identifying materials were securely stored and accessible only to the principal investigator.

Findings

At the conclusion of the data collection, there were 60 completed surveys and from that pool 12 completed interviews. The findings revealed layered factors that contributed to additional hardships for DACA recipients. Their voices relay some of the burdens they faced and the complex roles they held.

Findings from the survey participants (n=60)

The findings from the 60 completed surveys provided information of the participants’ experiences as a Daca recipient during the pandemic.

In the chart above, the colorful lines demonstrate how DACA status affects the participants in various aspects of their lives: mental health, schoolwork, personal relationships, career goals, community involvement, personal goals, and access to healthcare. The responses were on a scale from: not at all, a little, a moderate amount, and a lot. The blue line represents mental health, green schoolwork, purple personal relationships, coral career goals, pink community involvement, light blue personal goals, and pink access to healthcare. Daca status had the greatest impact on participants’ career goals, personal goals, mental health, access to healthcare, and personal relationships. The survey had additional short essay questions that gave participants an opportunity to describe the specific effects for each aspect of their lives mentioned. These responses were statistically analyzed for significance and examined through content analysis and integrated into the main themes that emerged in the 12 in-depth interviews, that are discussed in the interview section later in the paper.

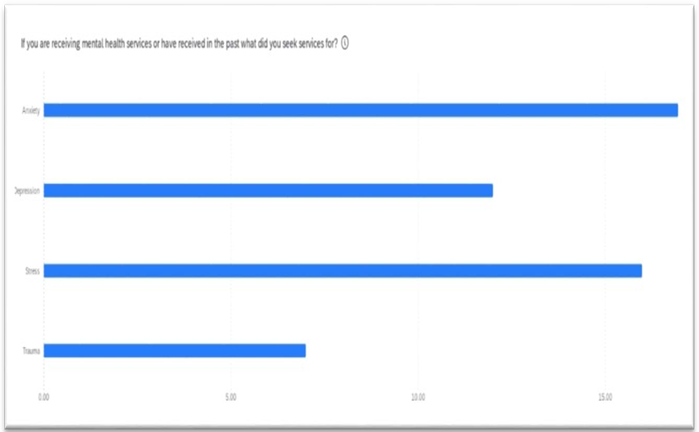

graph showing the utilization of mental health services.

The graph above shows the number of participants that obtained mental health services. The majority of those who responded to this question obtained mental health services for anxiety. Stress was the second highest reason for obtaining mental health services, followed by depression and then trauma.

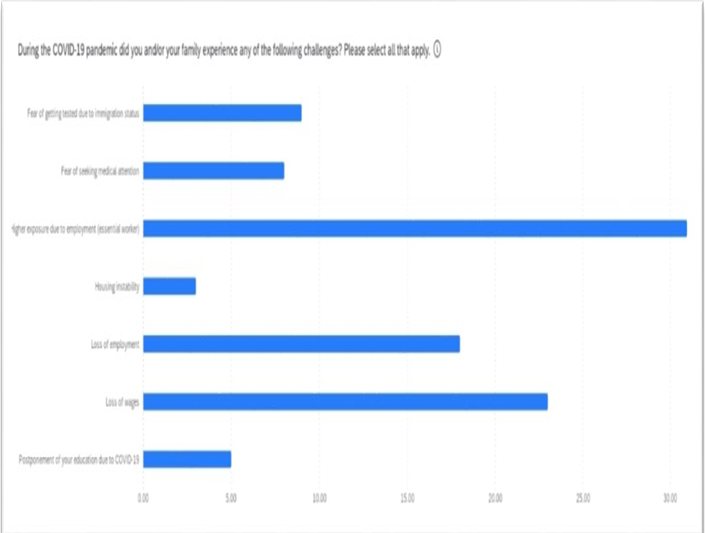

The graph above shows the responses of the survey participants to the questions about challenges experienced. The largest response was to have a higher exposure to Covid-19 due to their employment in essential worker positions. The second greatest challenge was the loss of wages. In the interviewed sample this was also noted with an emphasis on the anxiety this caused their family because they were the primary wage earner due to their ability to obtain work permits due to DACA. The third highest survey response to the challenges question was to the challenge of losing their employment entirely. Fear of seeking medical attention and getting the vaccine due to fear of “outing” their undocumented, non Daca eligible, family members was the next highest challenge, followed by needing to postpone their education and experiencing increased housing instability due to loss wages or jobs and the need to move into their parents’ homes in order to remain “a safe pod” during the pandemic.

Findings from Interviews (n=12)

The 12 interviews revealed further details that fleshed out and deepened the findings. Three major themes emerged from the interviews. These themes were also represented in the short essay questions of the survey. The themes are 1) increased responsibilities to family; 2) increased fear for health and for deportation of self or family members; 3) feeling unvalued as an essential worker, especially due to prejudice regarding their insecure resident status.

Graph depicting challenges reported by survey participants

Increased responsibility to family

The participants reported that throughout their lives they have been the interpreters and cultural liaisons for their family. During Covid-19, they were needed more by their families. The participants felt responsible to read up on the vaccines and encourage their parents to get vaccinated. Employment was challenging.

When vaccines became available, the participants felt caught between their family’s distrust of the government and their requirements to be vaccinated in order to work or attend school. The interviews revealed layers of stress regarding vaccination. The participants often had a different assessment of the vaccine than their families. One participant described it this way:

I work in a health setting so I see how the vaccine helps. When it became available, I was like ‘mom, you gotta go get it’, and she was like ‘I won’t and you shouldn’t either. How do we know they are safe?’ Well, as you can see, I had my work cut out for me. I had to convince my family that I am out in the world and know things they don’t. I also wanted them protected from me bringing home Covid. But the biggest hurdle was getting them to trust that this wasn’t going to get them deported.In the United States, vaccination became a challenge for DACA recipients as families sometimes felt distrustful of the DACA person’s motivations in encouraging vaccination. This participant described well how that felt:

I tell my parents that this isn’t some political conspiracy. It is a virus, and it can kill you. But they have heard so many threats about deportation and so many promises for immigration reform, they think it is another lie. They doubt me. My mom asked why I was pushing her so much to get vaccinated. ‘Because I don’t want you to die!’

Increased fear for health and for deportation of self or family members

While they appreciated being able to work, they feared bringing home the virus to their multigenerational home. When the Center for Disease Control (CDC) [30] advised households to have small pods where the most vulnerable family members are separated from those working in highly transmissible work environments, one participant succinctly stated, “If one in my household gets covid, we all get covid.”

During this time, forced migrants continued to cross the Mexican border to enter the United States illegally [31]. In the news, this crossing was framed as a threat to the health of US citizens. This increased their fear of being discriminated against or deported [31]. This quote from a participant conceptualizes the layers of fear experienced:

It’s been hell. Like we aren’t hated and feared enough? I find out I am not a citizen of the only country I have known. I eventually figure out how to apply to DACA and get it. I start, just start, to feel safer when immigration and customs enforcement (ICE) do these swipes through factories and arrest a bunch of undocumented workers. Then Covid. So yeah, I haven’t felt safe for a long time. I really feel like the US uses us. We are the essential workers during this whole covid thing and yet they don’t make sure our workplaces are safe, or that we have enough masks and tests, or any understanding really about how hard it is for DACA people.

Feeling unvalued as an essential worker

Many felt profoundly hurt by how the public treated essential workers. This participant described the multiple layers of hurt:

This is the only country I have ever known. I cheer the state’s sports teams, I pay taxes, I contribute to the economy. My parents who are not legally here also contribute. They pay sales taxes and work in the agricultural fields. Seriously, it makes me so mad. Every produce people put on their tables at dinner got there because of hard workers like my parents. On the news, we essential workers are like heroes. And then we go into work and feel like sacrificial lambs. I put myself in jeopardy so people can shop, and no one thinks anyone safe from the virus. Don’t get me started on how the customers treated us. The anti-maskers made all of us terrified of approaching anyone. Each morning I ask myself, ‘Will I get punched in the face today or die of covid’. And then, we are still being threatened with deportation. Yeah, sure, they treat us like heroes (stated sarcastically).

There were several missteps that the participants believed made vaccinations more difficult. Participants reported that there was not enough public information in Spanish about the vaccines, especially in places where their family might see, like on television, by celebrities they could relate to, at grocery stores, at bus stops, and other locations that could have reinforced the message. The message was as important as the messenger. As one participant stated, “We needed to hear it (Covid, vaccine) from people we trusted in our own communities.”

Discussion

The findings support existing research regarding the responsibility DACA recipients often have to family members, especially parents, who are not protected by DACA. This is important, especially in the context of a pandemic. As the nation, and the world, reflect on the pandemic and how better to respond to future pandemics, the experiences of those most vulnerable and burdened can inform future policies. While knowledge of the insecurity and burdens of DACA recipients pre-pandemic exists [18,31] it is critical to examine how those insecurities and burdens are exacerbated during chaotic and overwhelming events. It is not only compassion and concern for vulnerable groups that should motivate further research, but also for what that research means to the wider population. Like the canary in the mine, our most vulnerable groups’ experiences foretell the weaknesses of our nation’s policies and institutional systems. The Covid-19 pandemic revealed holes within our systems of healthcare delivery, employee protections and rights, economic safety nets and protective bolsters, and made stark the paradox of the lack of protections we provide immigrants and the responsibilities and burdens we expect from them.

The ecological theory provides multiple lenses to view the pandemic. On the micro level we can view the strengths and challenges of the individual Daca worker who provides for their family and the nation while many others were able to retreat temporarily to a safe pod with remote work. On the mezzo level we can see how schools, communities, and the healthcare system struggled and how these struggles increased the stress, fear, and risks for Daca recipients. On the macro level the Covid-19 pandemic exposed the interdependencies of individuals, systems, and communities and suggests that how we treat the most vulnerable reverberates to our economy, globalized supply chain, vaccine production and distribution, national identity, and regional and global health. We are interconnected and the policies we implement reverberate and reflect how prepared and willing we are to increase global protective forces to counter our world’s growing risks.

The COVID-19 pandemic necessitated a reevaluation of priorities by nations to accommodate public health needs and address supply chain challenges. In this process of adaptation, social disparities and economic inequities have become glaringly evident. While the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United States’ Centers for Disease Control advised people to form small pods and protect those at higher health risk, many workers continued to live in multi-family households [30]. Grocery store clerks and warehouse workers, alongside health professionals, emerged as essential workers during the pandemic, even as remote work became the norm for others. These essential workers continued to face risks to their safety.

The pandemic also brought into focus the disadvantages faced by forced migrants due to insecure immigration status. Limitations in policies, often designed to rectify problems or allocate resources, were laid bare during the global upheaval. Stressful times revealed the prejudices and systemic inequalities perpetuated by policies that deny human rights to specific groups. Individuals eligible for the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program are acutely aware of the social injustices they navigate. Once feeling like legal citizens with implied rights and privileges, they now find themselves part of the essential workforce while simultaneously being discriminated against and denied civil rights.

The pandemic underscored our interconnected world. Rather than viewing social ills and environmental changes as nation-specific, we must recognize them as global challenges. As global citizens, we need to reimagine our world, focusing on collaborative solutions to combat social injustice, unequal resource distribution, war, climate crises, and even microscopic threats like viruses. By perceiving these issues as shared global problems, we move closer to effective solutions and farther from xenophobic policies.

As we contemplate the end of this pandemic, questions arise: How will DACA-eligible individuals and other forced migrants fare? Will they receive recognition for their contributions during COVID-19? Will they be treated as equal citizens with full rights and privileges? If not, how can a country reconcile using them to keep society functioning while simultaneously denying them essential human rights? Forced migrants grapple with multiple stressors and often live in fear. DACA recipients, in particular, inhabit a liminal space between their parents’ country and the United States. Childhood experiences of feeling American give way to the realization that they don’t fully belong anywhere. COVID-19 served as a stark reminder that their temporary DACA protection remains just that— temporary—and they must reapply when needed. And when they need to reapply for DACA, will the program still exist? Will they be forced to leave the only country they have known?

Limitations of the Study

This study captured the experiences of 60 DACA recipients through a survey and 12 individual interviews from the survey participants. Data collection occurred during the pandemic and from one region in California. The confidentiality of the participants was paramount and required special considerations during recruitment and data collection. Recruitment needed to be largely initiated by the future participant so that they had control of self-identifying as a DACA recipient versus someone identifying and approaching potential participants. Interviews needed to be remote due to the virus. The principal investigator (PI) is not an immigrant, nor from the communities represented in this study. Therefore, data might be biased due to the self-selected structure of recruitment. It is possible that those who volunteered to participate were motivated by some experience that may homogenize what could be a more heterogeneous pool of potential participants. The PI might interpret the data through their own cultural view and miss nuances and meanings that someone from the same culture and DACA experiences would perceive. The geographic region being studied is influenced by its strong university presence, a large agricultural labor force that employs many undocumented workers, and liberal politics. Future studies should collect data from other regions and states. The survey provided useful data and could be effectively administered to larger groups.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed the toll inequality takes on poor and marginalized people. Specifically, DACA recipients with insecure immigration status are burdened by their role in caring for their families, being essential workers on the frontline of exposure to COVID-19, and with the threat of deportation looming. Additionally, DACA recipients during the pandemic had to manage their parents’ anxiety regarding COVID-19 precautions and vaccines amidst the onslaught of misinformation and lack of sufficient public health information in Spanish.

The ecological theory provided a broad view of the areas of life impacted by the virus and discrimination. In addition to the participants’ health, they were also affected psychologically, socially, and economically. The ecological theory also enhanced understanding of how one’s life stage can affect the impact of these stressors. The participants of this study were adults under 30 years old, a developmental age when individuals are focusing on advanced schooling and entry-level work. If this sample were older or younger, these results might differ, and the layers of stress vary. For this sample, school, work, and family defined their concerns, and thereby these areas are reflected in the data.

Through the lens of ecological theory, the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact is layered among the various spheres of influence (biological, psychological, socio-economical). For DACA recipients, that adds to an already layered and complicated position. They are not citizens of their parents’ homeland, nor legal citizens of the United States. They once felt a sense of belonging. But once their immigration status was known to them, they felt separate from their parents, friends who have legal status, and from the country they have lived for most of their lives. They experience racial discrimination throughout their lives, even before they discovered their insecure immigration status. Once aware of their noncitizen status, they faced additional discrimination. When President Trump was in office, they felt increased fear from hateful rhetoric by xenophobic politicians. Then, with COVID-19, this increased fear was exacerbated by the stress of working in public, high-risk exposure settings. This was compounded when customers they served would not wear masks, yelled at the worker, and threatened to hit or hurt the worker because the customer was asked to wear a mask.

The toll on DACA recipients is beyond situational events—how will this period shape them a year from now, five years from now, or ten years? Studies have examined the consequences of forced migrants not feeling a sense of belonging [32]. The experience of living DACA during COVID-19 is layered. The first layer is their family’s culture during childhood. For many DACA recipients, their childhood was growing up as American. The second layer is racial discrimination. The third layer is when they discover they are not US citizens and could be deported at any time [33]. The fourth layer is immigration policies that can change with each election cycle or by spikes in xenophobia [34]. And the fifth layer is the global pandemic overlayed over. These layers extend to each sphere of influence in a DACA recipient. The COVID-19 has had a cumulative impact on each layer. The feelings of being on the outside when they first realized that they were undocumented grew in intensity during COVID-19. The confusion and fear they experienced navigating public services before they received DACA resurfaced with fear and confusion during the pandemic. Racist and hateful attacks that they experienced throughout their lives escalated as anti-mask customers attacked them at work. And when the vaccines were available, DACA recipients were in the middle of a familiar space that is divided between their family and their country.

Implications

The implications implied from this study are that to effectively implement a public health campaign, which includes those who have insecure immigration status and a history of being systematically discriminated (not only incidental events of discrimination), must acknowledge these layers discussed and address those they can. When better understood, these layers can be avenues to reach each community member. For example, if a public health entity wanted to outreach to a specific group, knowing the layers in which that member resides can expand the methods to reach them. One might reach out to cultural groups, language interpreters, neighborhoods, youths, adults, and older adults. However, this is not a siloed approach of delivering information or services to different venues but to approach outreach as a holistic system, separate systems operating together as a larger system. Hospitals, community health clinics, schools, and the media can provide a collective response to health crises. Working together, they can inform the public, and in particular marginalized groups, via culturally effective information about Covid-19 regardless of health mandates (mask mandates, proof of vaccination).

This study also presented a stark contrast between the myth that immigrants drain the economy and the reality of these workers being the essential workers that keep the economy going when so much of the nation was shuttered at home. This pandemic will be studied for years. Microbiologists will dive into the virus to learn its architecture, political scientists will discern the influences that created the political reaction to the pandemic, and social scientists will explore the lived experience. This study reflects the voices of sixty who are experiencing Covid-19 within layered lived experiences.

Funding and/or Conflicts of Interests/Competing Interests:

The author reports no funding or conflict of interest with the study or the article’s publication.

References

Center for American Progress (CAP). (2021). The economic and social contributions of DACA recipients: A state-by-state analysis. Retrieved from: DACA Recipients ContributionsView

Becerra, C. (2019). Keep the dream alive: the DACA dilemma. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 40(6), 847-858. View

Aranda, E., Vaquera, E., Castañeda, H., Rosas, G.M. (2023). Undocumented again? DACA rescission, emotions, and incorporation outcomes among young adults, Social Forces, Volume 101, Issue 3, March, Pages 1321–1342.View

Patler, C., Hamilton, E., Meagher, K., & Savinar, R. (2019). Uncertainty about DACA may undermine its positive impact on health for recipients and their children. Health Affairs, 38(5), 738-745.View

Papademetriou, D. G., Benton, M., & Banulescu-Bogdan, N. (2017). Rebuilding after Crisis: Embedding Refugee Integration in Migration Management Systems. MPI, Washington DC. View

Department of Homeland Security. (2019). Retrieved from: DHS Immigration and Customs Enforcement.View

Potochnick, S. R., & Perreira, K. M. (2010). Depression and anxiety among first-generation immigrant Latino youth: Key correlates and implications for future research. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 198(7), 470.View

Siemons, R., Raymond-Flesh, M., Auerswald, C. L., & Brindis, C. D. (2017). Coming of age on the margins: Mental health and wellbeing among Latino immigrant young adults eligible for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA). Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 19(3), 543-551.View

Fuligni, A. J. (2020). Is there inequality in what adolescents can give as well as receive? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 29(4), 405–411.View

Institute of Taxation and Economic Policy. (2022). Retrieved from: ITEP Migrant SearchView

Batalova, J., Fix, M., & Creticos, P. A. (2008). Uneven progress: The employment pathways of skilled immigrants in the United States. Washington, DC: National Center on Immigrant Integration Policy, Migration Policy Institute. View

Luna, Y. M., & Montoya, T. M. (2019). “I need this chance to… help my family”: A qualitative analysis of the aspirations of DACA applicants. Social Sciences, 8(9), 265.View

Amuedo-Dorantes, C., & Antman, F. (2017). Schooling and labor market effects of temporary authorization: Evidence from DACA. Journal of Population Economics, 30(1), 339-373.View

Williams, M. T., Printz, D., & DeLapp, R. C. (2018). Assessing racial trauma with the Trauma Symptoms of Discrimination Scale. Psychology of Violence, 8(6), 735.View

Sanchez, R. E. C., & So, M. L. (2015). UC Berkeley’s undocumented student program: Holistic strategies for undocumented student equitable success across higher education. Harvard Educational Review, 85(3), 464-477. View

Rousseau, C., & Frounfelker, R. L. (2019). Mental health needs and services for migrants: An overview for primary care providers. Journal of Travel Medicine, 26(2), tay150. View

Enriquez, L. E., Morales, A. E., Rodriguez, V. E., et al., (2023). Mental Health and COVID-19 Pandemic Stressors Among Latina/o/x College Students with Varying Self and Parental Immigration Status. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 10:282–295. View

Cholera, R., Falusi, O. O., & Linton, J. M. (2020). Sheltering in place in a xenophobic climate: COVID-19 and children in immigrant families. Pediatrics, 146(1).View

Bishop, S. C., & Medved, C. E. (2020). Relational tensions, narrative, and materiality: intergenerational communication in families with undocumented immigrant parents. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 48(2), 227–247.View

Kusters, I. S., Gutierrez, A. M., Dean, J. M., et al. (2023). Spanish-Language Communication of COVID-19 Information Across US Local Health Department Websites. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 10, 2482–2489.View

Bono, G., Reil, K., & Hescox, J. (2020). Stress and wellbeing in urban college students in the US during the COVID-19 pandemic: Can grit and gratitude help? International Journal of Wellbeing, 10(3).View

Aragona, M., Barbato, A., Cavani, A., Costanzo, G., & Mirisola, C. (2020). Negative impacts of COVID-19 lockdown on mental health service access and follow-up adherence for immigrants and individuals in socio-economic difficulties. Public Health, 186, 52-56.View

Rothman, S., Gunturu, S., & Korenis, P. (2020). The mental health impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on immigrants and racial and ethnic minorities. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, 113(11), 779-782.View

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1992). Ecological systems theory. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.View

Germain, C. B., & Gitterman, A. (1995). Ecological perspective. Encyclopedia of Social Work, 1, 816-824.

Grant, J., & Guerin, P. B. (2014). Applying ecological modeling to parenting for Australian refugee families. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 25(4), 325-333.View

Närhi, K., & Matthies, A. (2016). Conceptual and historical analysis of ecological social work. In *Ecological Social Work: Towards SustainabilityView

Marley, C., & Mauki, B. (2019). Resilience and protective factors among refugee children post-migration to high-income countries: A systematic review. European Journal of Public Health, 29(4), 706-713.View

Vaismoradi, M., Turunen, H., & Bondas, T. (2013). Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing & Health Sciences, 15(3), 398-405.View

Feldmann-Jensen, S., & Kim, A. (2024). The first pandemic of the 21st century: The use of PODs in the 2009 public health response. In Case Studies in Disaster Response (pp. 123-140). Butterworth-Heinemann.View

Garrett, T. M., & Sementelli, A. J. (2022). COVID-19, asylum seekers, and migrants on the Mexico–US border: Creating states of exception. Politics & Policy, 50(4), 872-886.View

Blachnicka-Ciacek, D., Trąbka, A., Budginaite-Mackine, I., Parutis, V., & Pustulka, P. (2021). Do I deserve to belong? Migrants’ perspectives on the debate of deservingness and belonging. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 47(17), 3805-3821.View

Benuto, L. T., Casas, J. B., Gonzalez, F. R., & Newlands, R. T. (2018). Being an undocumented child immigrant. Children and Youth Services Review, 89, 198-204.View

Knopf, A. (2017). DACA shut down by Trump; children and families need help from Congress, providers, and us. The Brown University Child and Adolescent Behavior Letter, 33(S10), 1-2.View