Journal of Social Work and Welfare Policy vol. 2 iss. 1 (2024), Article ID: JSWWP-117

https://doi.org/10.33790/jswwp1100117Research Article

Fear of Crime Among College Students with Disabilities

Tracey Steele1, Ph.D., Sarah E. Twill2*, Ph.D, M.S.W., and Jacqueline Bergdahl3, Ph.D.,

1Associate Professor, School of Social Sciences and International Studies,Wright State University, 3640 Colonel Glenn Highway, Dayton, OH 45435, United States.

2*Professor, Department of Social Work, Wright State University, 3640 Colonel Glenn Highway, Dayton, OH 45435, United States.

3Professor, Department of Sociology, Wright State University, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Sarah E. Twill, Ph.D, M.S.W., Professor, Department of Social Work, Wright State University,3640 Colonel Glenn Highway, Dayton, OH 45435, United States.

Received date: 05th March, 2024

Accepted date: 04th July, 2024

Published date: 06th July, 2024

Citation: Steele, T., Twill, S. E., & Bergdahl, J., (2024). Fear of Crime Among College Students with Disabilities. J Soci Work Welf Policy, 2(2): 117.

Copyright: ©2024, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Abstract

This research explores how temporal factors may differentially affect the experiences of students with and without disabilities regarding their fear of criminal victimization. Prior research has found that college students with disabilities have greater fear of crime during the day when compared with students without disabilities. In this research we confirm this finding and expand the practical implications of this reality for campus Disability Service offices. Possible explanatory mechanisms about causes of this difference and the ways in which universities can work to create a campus environment that is conducive to a sense of safety and security for all students are explored.

Keywords: Disability, University Students, Vulnerability, Campus Safety, Policy

Introduction

Campus administrators face a host of challenges when attempting to provide an accessible and safe environment for students with disabilities, not the least of which is the tendency for persons with disabilities to experience higher rates of criminal victimization than those without [1]. And while large amounts of human and financial resources may be expended on campus safety, these efforts may do little to ameliorate individual-level concerns students may hold about victimization (better known in the literature as ‘fear of crime’).

Some groups have more risk of victimization than others such as the young, males, those in residential locations [2], persons of color [3], and those with disabilities [1,4,5]. Conversely, others have a lower risk of victimization including those who are older, female, white [6], and non-disabled [7]. Fear of crime – the perceived risk of being a victim of crime – is also quite variable and is related to different personal, group, and environmental conditions. For example, as we age, our fear of crime or our anxiety about becoming a crime victim increases, but our risk of criminal victimization actually declines [6,8]. Younger people (18-24) are the most likely to be victims of crime, but the least likely to fear it.

In this study, we use a sample of college students at a Midwestern United States public university to explore temporal differences between the experiences of students with and without disabilities regarding their fear of criminal victimization. Prior research has found that college students with disabilities have greater fear of crime during the day when compared with students without disabilities [5]. The relatively new finding warrants further assessment and consideration as to how campuses, specifically Disability Service offices, might enhance policies and procedures that could help students with disabilities feel safer on campus.

Fear of Crime

A meta-analysis by Collins [9] examined individual and neighborhood characteristics predicting fear of crime and found it was higher for females, those with prior victimization, and those who lived in high-crime neighborhoods or neighborhoods that contained physical incivilities (abandoned buildings, litter and graffiti and other signs of social disorder). Whites reported less fear of crime as did those with higher police satisfaction or higher collective efficacy (the ability of neighborhoods to maintain effective social controls). Sex had the strongest relationship with fear of crime (more so than previous victimization experience), followed by neighborhood-levels factors of collective efficacy and physical incivilities. Education and age had no effect on fear of crime, but nighttime has been found to increase crime fears [10,11]. Collins [9] also points out the unique role of the U.S. regarding fear of crime: we have more fear than other nations and race plays an important part important in those differences. Trust in the authorities is likely a factor.

In addition to these factors, more recent research has utilized a vulnerability framework to explain variations in fear of crime. This framework holds that socially vulnerable and marginalized populations are more likely to be fearful of criminal victimization [12]. Cossman and Rader [13] found that perceived health predicted fear of crime. In that study, reported health status was a precursor to fear of crime as it adds to one’s perception of vulnerability. That is, individuals are fearful of crime because they feel physically vulnerable to victimization. Later, Cossman, Porter, and Rader [14] tested whether physical (gender, age, health) or social (race, education, marital status) vulnerabilities contributed to fear of crime. They found both contributed but were mediated by each other. Being in poor health increased the likelihood of feeling unsafe more frequently, and education, race, and marital status all affected health. The authors suggest that social vulnerabilities as related to fear of crime indirectly influence physical vulnerability, and vice versa.

Fear of Crime on College Campuses

Like fear of crime in the general population, several factors have been shown to effect fear of crime on college campuses. This includes females having more fear of crime than males [15,16] students of color having more fear than whites [17] and prior victimization predicting more fear of crime than those not experiencing victimization [5,18].

The literature finds differences in environmental factors as well. Fear of crime typically differs between on-and off-campus locations with those on-campus generally reporting high levels of fear [19]. Similarly, Steinmetz and Austin [16] found men living off-campus were less fearful than men living on-campus. They also found that some specific physical locations on campus (a tunnelled walkway) elicited more fear of crime than others [16]. Conversely, Crowl and Battin [18] found those living off campus reported more fear of crime although that was only the case for one of the two campuses they studied.

Daigle, Hancock, Chafin, and Azimi [20] compared US college students to Canadian college students’ fear of crime. They found that the Canadian students perceived themselves to be safer in all contexts and settings except on college campuses. The authors hypothesized public policies in the countries may help explain these differences. For example, Canadian students have been raised with stricter gun control policies and have avoided practicing for school shooting incidents, resulting in lower crime fears. However, when they arrive to US college campuses, they receive required Cleary notifications (no similar policy requires Canadian students to be notified of campus crime) and other campus reports of crime which may lead them to believe campus is unsafe.

Disability and Fear of Crime

Pyo and Haeysm [21] studied hate crimes and perceived fear of crime among adults with disabilities. They created a model to determine if the perception of fear of a hate crime was functional or dysfunctional to the lives of peoples with disabilities. They found that people with disabilities were more likely to have a dysfunctional perception of fear of crime, both related to anti disability hate crimes and other hate crimes. Further, those with intersectional identities, such as race/ethnicity and/or sexually identity, along with disability experienced more dysfunctional perceptions of fear of hate crime than those who identified as a person with disability only.

Students with Disabilities and Fear of Crime on Campus

Using a national database that included students from 137 Higher Education Institutions, Daigle and colleagues [5] explored the relationship between students’ disability status, victimization experiences, and fear of crime. They found that across a variety of conditions, students with disabilities were significantly more fearful and more likely to have experienced victimization than their peers. They explored the relationship between victimization experiences and students’ sense of safety however, they found that victims with disabilities felt just as safe as the other students—that is, the intersection of victimization and disability status failed to further abate students with disabilities’ sense of safety. Daigle and colleagues hypothesized this might be because students with disabilities already have such high levels of fear that victimization does not increase their fear. Their research also revealed that students with a disability were 33% more likely to be fearful during the day when compared to students without disabilities.

Using a national database that included students from 137 Higher Education Institutions, Daigle and colleagues [5] explored the relationship between students’ disability status, victimization experiences, and fear of crime. They found that across a variety of conditions, students with disabilities were significantly more likely to have experienced victimization than their peers. While the authors were the first to report the finding of significantly greater daytime fear of crime for students with disabilities, the finding was part of a larger study. The authors gave little attention to what this finding may mean for students with disabilities and how colleges could respond to the fear through social and policy actions. Further, though campuses disability offices recognize and serve students with mental health issues, Daigle et al.’s study did not include mental health conditions within their disability construct and their measure of fear of crime was limited to measures of location (on and off campus) and time of day (night) and did not include other considerations related to fear of crime such as variations in the type of crime considered and the and the nature of the apprehension (i.e., fear of crime versus the expectation or likelihood of being criminally victimized).

This study will attempt to fill this gap and further explore students with disabilities fear of crime on college campus during daytime hours. Our study included mental health as one possibly disabling condition and crime type and the nature of the apprehension. Following data collection and analysis, we interviewed several key informants with disabilities on campus to further understand reasoning for fear of crime during daytime hours. As a result of the data analysis and key informant input, we propose changes campuses could make to help reduce fear of crime for students with disabilities.

Methods and Materials

Participants

The data for this research was part of a larger survey project concerned with evaluating the efficacy of several predictors of college students’ fear of crime. Responses were gathered from anonymous online surveys of 540 students attending a Midwestern United States public university at both its main and satellite campuses.i

The students who participated in this research primarily identified as Caucasian (74.2%), with 10.2% self-identifying as African American and a combined 15.8% selecting another racial/ethnic category. This sample was somewhat more likely (p<.05) to be White (74.2% in sample versus 68.9%) and female (56.6% versus 51.7%) compared to the University as a whole. Additionally, respondents were most likely to classify themselves domestic students (85.4%) holding the rank of college senior (24.5%). Overall, the sample ranged from 16 to 58 years old with an average age just under 26. And, while more of these students identified as socially liberal than socially conservative (45.7 versus 34.1%), they reported significantly greater affinity with fiscal conservatism than fiscal liberalism (45.5 versus 22.7%). Finally, a total of 47 students (8.7% of the sample) were classified as having a disability with the remainder (493) classified as being students without a disability (91.3%).

Measures

Fear of Crime During the Day

In order to assess students with disabilities’ relative apprehension about criminal victimization during the day, we constructed the daytime fear of crime (FOCDAY), as a scale comprised of eight randomized 5-point Likert-scale items representing all possible combinations of three dichotomously-situated contexts that have been utilized in prior work on this topic.ii

The first of these three contexts involves variations in fear of crime that may be related to the kind of criminal activity in question. Ferraro [11,15] was among the first scholars to find evidence that for women, fear of crime is disproportionately linked to the fear of sexual assault (for a review, see [22]). Therefore, it is important to distinguish between a general fear of crime among respondents and fear of the more specific crime of rape or sexual assault [15,23-25].

Location is another important context that has been found to impact victimization concerns. Fisher [26] found that crime fears can be particularly high on college campuses and a host of other researchers have included this consideration within their fear of crime constructs [27,28]. To determine if this holds for students with disabilities as well, we included items that separate location into two measures, one that references on-campus concerns and another assessing victimization fears for off-campus locations.

Finally, because previous research has identified important distinctions between different dimensions of fear of crime including emotional (e.g. worry about crime) and cognitive aspects (i.e., the perceptions of danger and/or the likelihood of criminal victimization), the third context includes measures of both conditions [24,29]. This is a particularly salient issue to consider given that individuals with disabilities are significantly more likely to experience victimization [5,30,31] which may increase their estimates of the likelihood of victimization. Therefore, differentiating between emotional and cognitive dimensions may provide a more nuanced understanding of the underlying mechanisms shaping variations in crime concerns for our sample.

Each of these contexts were constructed with dichotomously ‘toggled’ measures resulting in eight unique conditions. Half of the indicators represent the presence of one condition and the other half of the indicators represents the other. For example, scale item 1 asks: “When you are on campus, how afraid are you of being a victim of crime during the day?” This question reflects the daytime on- campus, fear, and criminal victimization conditions while scale item two: “When you are off campus, how afraid are you of being a victim of crime during the day?” assesses the daytime off-campus, fear, and criminal victimization condition. The items for each of the conditions are rotated out sequentially until every combination has been exhausted.The result is the 8-item, Daytime Fear of Crime scale (FOCDAY) with a Chronbach’s Alpha of .917 which exceeds the accepted minimum standard of .70 (See Appendix X).

Disability Status

The other key study variable was disability status which was constructed from the survey item “I have a disability”iii . Response categories included ‘Yes’, ‘Maybe’, and ‘No’. Responses were recoded into the dichotomous variable SWD (student with a disability) such that responses categorized as ‘No’ were coded as ‘0’, and those listed as ‘Yes’ as ‘1’.iv

Additional Measures

Other measures included in the analysis were the respondents’ self reported age (measured in whole years), race (recoded from eight racial and ethnic categories as ‘NonWhite’ coded as ‘1’ and ‘White’ coded as ‘0’), and biological sex (recoded from five sex categories with ‘Female’ coded as ‘1’ and, ‘NonFemale’, coded as ‘0’.

Results

Descriptive and Mean Comparisons

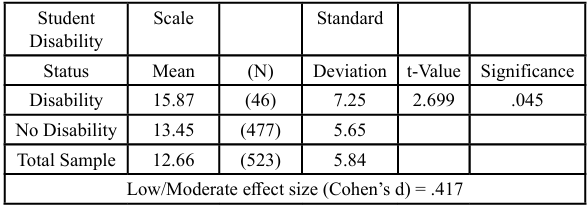

Values for our measure of daytime fear of crime (the 8-item FOCDAY scale). ranged from a possible minimum value of 8 to a maximum of 40 with a midpoint of 24. As shown in Table 1, in our sample, students’ overall mean FOCDAY score was 13.66 (SD=5.84). This reflects low to moderate levels of daytime fear of crime among our student participants.

An examination of bivariate correlations related to disability status confirms the stark contrast in daytime fear levels between students with and without disabilities. FOCDAY scores for students with disabilities in our sample posted a mean of 15.87 (SD 7.25), while their peers notched daytime fear levels of 13.45 (SD 5.65), a difference that is statistically significant (N=523, Pearson Correlation Coefficient (.117), p<.01).

A two-sample t-test was conducted to provide a more robust analysis of the effects of disability status on daytime fear of crime scores. The results confirmed Daigle et al.’s [5] recent finding of significantly higher fear of crime levels during the day for students with disability (M = 15.87, SD = 7.25) compared to students without disability (M = 13.45, SD = 5.65), t (521) =-2.699, p<.01. with small effect sizes (d=-.229).

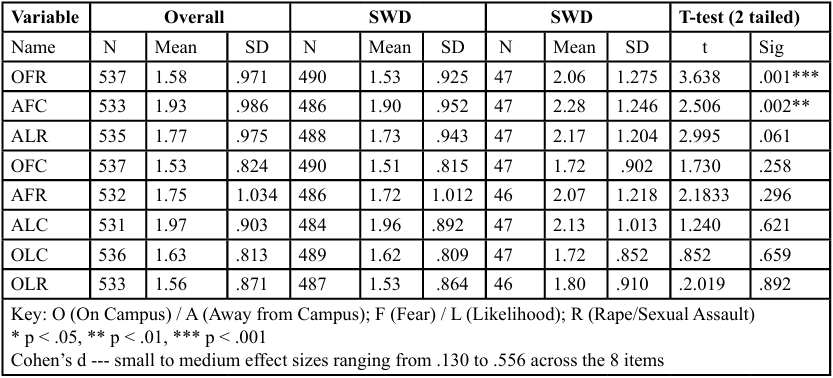

A closer examination of the eight variables comprising the FOCDAY scale (see Table 1) reveals that although overall levels of fear for both students with and without disabilities were relatively low across each of the eight daytime measures, for two of these measures (AFC and OFR), the t-test shows that the difference in fear between students with and those without disabilities was statistically significant. Further, both items shared a focus on fear, rather than the likelihood of crime. In fact, none of the likelihood items attained significance suggesting that prior victimization does not necessarily increase student with disabilities’ sense that the likelihood of crime is higher than it is for students without disability (this result is consonant with Daigle et al.’s [5] findings that prior victimization did not increase fear of crime for students with disabilities beyond levels that could be accounted for by disability status alone).

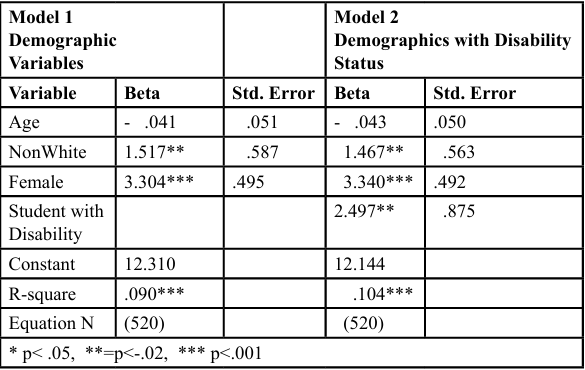

To account for the possibility that other factors related to disability status might be causing the apparent relationship between SWD and FOCDAY, OLS regression analyses were conducted to establish that gender and race, while significant, were insufficient to account for the independent effect of disability on heightened fears of daytime victimization (See Table 3).

Discussion

This study found students with disabilities are more fearful of crime during the day. Our findings suggest that daytime feels more dangerous to students with disabilities when compared to their collegiate peers, supporting Daigle, et al.’s [5] findings. We examined the effects of sex, age, and race in regression analyses and significantly higher daytime fear levels persisted for students with disabilities even when these factors were considered.

Further, examination of the eight items that compose the scale, indicates fear of rape on campus and fear of crime off campus are the main items contributing to this result. Disability status was consistently unrelated to the four likelihood of crime measures despite the fact that the students with disability in our sample had higher rates of prior victimization. Consistent with Daigle et al. [5], it may be the case that that that having a disability may, in and of itself, raise crime fears to such a level that actual victimization experiences fail to move the needle of fear.

In order to learn more about potential daytime crime fear, we consulted four key informants from the university’s Office of Disability Services – two students (both of whom identified as having a disability and used a wheelchair) and two staff members (neither of whom disclosed their disability status, but each of whom had 20+ years’ experience working with students who have disabilities). These informants were not intended to represent our sample or our university, but rather, were approached to provide some face validity to our finding of fear of daytime crime. Their insights helped us develop explanatory mechanisms as to why this pattern may occur.The first possibility is that students living with a disability may be more active during the day; therefore, they have greater exposure to people and contexts that increase their sense of vulnerability than they do at night. For example, the university offers registration preference to some students with disabilities (contingent on need and student’s personal accommodation plans) and all students who are veterans with disabilities. This makes daytime class blocks more readily available. Additionally, students, especially those with physical disabilities, may feel more comfortable negotiating their surroundings during daylight hours. One informant who uses a wheelchair discussed the difficulty of negotiating curb cuts when it is dark; as a result, she reported engaging in as many daily activities as possible (e.g., shopping, visiting friends) while it was light out to decrease the effects of this issue. Another informant expressed that their medical condition made them more tired as the day progressed. Because of this, they tended to return home in the early evening and not go out again. In short, both university policy and student preferences may push students with disabilities into the community during the day, exposing them to unfamiliar people and challenging environments that may increase their sense of vulnerability and fear of crime.

Another explanatory mechanism relates to students with disabilities’ use of personal assistants (PAs) who help with daily living skills including self-care, showering and assistance with toileting. On our campus, students with significant physical disabilities may encounter PAs in two ways. First, students who require daily assistance can either contract with the university or local health care agencies providing trained individuals to assist with care [32]. However, student consumers will likely screen only the agency, not the individual provider of the services. Given the intimate nature of the services rendered and the lack of autonomy in selecting the PA, individuals with disabilities may fear their PA has opportunity to exploit them. Allowing students more autonomy to screen their PAs may increase their self-determination and lesson their fear of crime, especially for students who may have experienced physical bullying or other boundaries violations and inappropriate touch. Such efforts may be one way to increase agency and decrease dysfunctional fear of crime as suggested in the Pry and Haesym [21] research. One of the student informants reported that she worked very hard to keep the same PA from semester to semester given the time and trust that went into the relationship. Secondly, the university provides a personal assistance station for students with disabilities; the staff can assist students in restroom use, body repositioning, and mobility device transfers [33]. In the term this study was conducted, 15 PAs worked at the PA station. This means a student with a disability may have encountered up to 15 different people in an intimate-care situation.

While the aforementioned rationales for fear of crime have focused on students with physical disabilities, there are also reasons that students with mental health diagnosis may experience fear of crime during daytime hours. Students with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and other social anxieties may encounter people and situations on campus and in the classroom that trigger their fears. It should be noted that our data was collected pre-pandemic and the landscape of mental health has changed wildly [34] and additional research about how students with mental health experience fear of crime should be explored to better understand these experiences.

The final mechanism stems from bullying experiences some students with disabilities may have experienced during their K-12 education. In fact, Beadle-Brown and colleagues found that people with learning disabilities listed school as one of the primary places “where bad things happen” [35]. It has been well documented that students with disabilities experience more bullying and harassment than their non-disabled peers [36-39]. Further, it is likely that peer bullying took place during daytime hours as crimes committed by juveniles peak at 3-4 p.m., the end of the school day [40]. As a result, being bullied as a youth may create lingering fears for students with disabilities that endure into adulthood [42]. In short, the trauma associated with prior experiences of daytime bullying may persist and make students with disabilities more fearful of criminal victimization during the day.

Next Steps

On Campus

Previous studies have found that social capital [42] and collective efficacy [43] correlate with local fear of crime. While these studies focused on low-income communities with characteristics such as abandoned buildings, feeling like a disenfranchised community may impact students on campus. Given that Collins [9] found that collective efficacy and incivilities were the third and fourth most impactful predictors of fear of crime, campuses should consider programming designed to increase campus safety and inclusiveness.

There are several steps universities can take to attain these goals. First, campus disability offices could host workshops about campus crime and safety procedures. Knowing how campus police may respond to a call, the availability of campus safety apps, and understanding ways to report campus crime may increase self confidence in students with disabilities. Student informants reported that they received general information about campus safety as part of their orientation for the university and in housing, but that the information was designed for the general student body population and did not attend to the specific risks relevant to this population.

Additionally, campus disability centers may consider facilitating campus discussions about bullying. Providing examples of types of bullying related to disability that have been experienced on campus, and ways to respond, can assist students with how to proceed if such issues arise. Assistance can address both personal responses (e.g., ways for the student to address bullies) and institutional resources (e.g., areas addressed by campus administration including housing, student conduct, and campus police). Further, trainers should be aware that prior victimization and beliefs about vulnerability may complicate a students’ perception of the information being presented in the workshop and be prepared to provide a referral to campus wellness and health services should additional mental health support be needed. Perhaps, a psychoeducational group could be co-offered by disability and wellness centers on campus to decrease fears about vulnerability and increase resilience. Based on the work of Pyo and Haeysm [21] and the knowledge that those with disabilities may overestimate the likelihood of criminal victimization, such policy and procedural efforts undertaken by universities can help students take common sense steps to both take steps to stay safe and realistically help students acknowledge the likelihood of campus crime and personal victimization.

Additionally, because we tend to be apprehensive of those we do not know, a second step would be to infuse greater human connection between students with disabilities and university personnel, particularly those in intimate-care settings such as University PA stations. This could include steps such as a “meet and greet” with the PAs and students likely to use the PA station. Meeting someone and chatting with them before they engage in touching required at a PA station is a simple and reasonable fear-reduction strategy. Students using the PA station should also have a voice in the hiring and retention of PAs. Similarly, including a student on PA hiring committees and creating student-based oversight mechanisms such as a survey of strengths and challenges of PAs could increase student input, and thus agency. In addition, to reduce turnover among staff, universities could examine the pay of the PAs to incentivize worker continuity from semester to semester.

Similarly, ODSs can strengthen students’ comfort on campus during the day by providing training for the campus community about working with students with disability. Modelling wider campus efforts after GLBTQ Safe-Space trainings, may benefit students, faculty, and staff, and allow students with disabilities to identify their campus allies. Efforts such as these would likely improve collective efficacy and decrease incivilities [9] and thereby reduce fear of crime on campus. These programming efforts are easy, typically cost little to implement, and may not only help lessen students with disabilities fear of crime on campus but enhance the full campus experience.

Study Limitations

This study had several limitations that need to be acknowledged when considering the findings. The finding of fear of daytime crime was a post hoc analysis as the data collected was part of a larger study related to campus safety and correlates fear of crime. As such, the survey provided little guidance for reporting or defining disability. Had the original purpose of the study been specifically on crime and disability, the authors would have operationalized a standard definition of disability so that students who were self reporting had guidance on how disability was being categorized for the purpose of the research. Additionally, the university in which the data was collected has a national reputation for serving students with disabilities and students come from across the state and country. It is possible that the participants have unique characteristics when compared to other campuses. Finally, the data was collected pre pandemic and changes in society have been significant.

Future Research

To address the methodological limitations of this (see above) and other studies related to disability and fear of crime, the community of scholars working in this area would be well-served to consider coming to agreement on several measurement issues. Considerations could include whether students have registered their disability with ODS and/or receive academic or student life accommodations. Similarly, definition-based descriptors of disability types may also help to determine if the nature of a disability (e.g. psychological, physical) differentially shapes victimization fears. Exploring the effects of additional types of crime would also help to clarify the relationship between disability, victimization, and fear of crime. In additional the definition of disability, research should consider the role of prior victimization and bullying and the most appropriate way to measure these histories to determine their role in fear of crime. Related, if there is a history of victimization, researchers should consider the timeframe to assess (i.e., one year, most recent, or lifetime) and the severity of the incident (i.e., ongoing bullying, multiple crimes, only ask about most significant event). Finally, researchers should question if difference considerations should be given to visible versus invisible disabilities as a factor in whether someone believes they are identified by others as an “easy” target of crime.

Given the finding of increased fear of crime during the day and its newness, future researchers would be well served to incorporate qualitative interviews with students to learn more about potential concerns. Semi-structured interviews would allow researchers to develop a rich understanding of experiences of students, different kinds of disability, different campus procedures that either reduce or intensify fear of crime, and different perceptions of crime and safety.

The results of this research offer rich possibilities for future research. For example, empirical exploration of the effects of youth bullying, perceived dependence and vulnerability, as well as greater human exposure and the effects of these factors on fear of crime for students with disabilities (as well as other marginalized populations), would help to elucidate important contextual variations in fear of crime. In addition, because our research was limited to university students at a single Midwestern United States public institution, exploration of these measures among other populations would be beneficial.

Beyond issues of measurement, research in this area could be greatly enhanced by partnerships with campus disability offices. These centers could offer informed assistance through solicitation of respondents, advertising research, and working with researchers to decrease the likelihood that issues of accessibility (e.g. the lack of sight, processing disorders) might prevent students with disabilities from research participation. As previously mentioned, it would also be helpful to have a mixed methods design so that university researchers and policy makers could hear directly from students. Focus groups about crime on university grounds and interviews with varying student populations to discuss and offer explanations for findings would further illuminate the experiences of students with disabilities on campus.

Conclusion

Fear of crime influences anyone’s ability to be an engaged and productive member of society. Our finding of students with disabilities having more fear of crime during the day warrants further attention, as fear and anxiety lower academic performance. Attention to these issues would help individual students’ wellness, increase retention and improve campus climate.

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Mueller, C. O., Pratt, A. J. F., & Sriken, J. (2019). Disability: Missin from the conversation of violence. Journal of Social Issues, 75(3): 707–25.View

Meier, R. F., & Miethe, T. D. (1993). Understanding theories of criminal victimization. Crime and Justice,17: 459.View

Lauritsen, J. L., & White, N. A. (2001). Putting violence in its place: The influence of race, ethnicity, gender, and place on the risk for violence.” Criminology & Public Policy, 1(1): 37–60.View

Daigle, L.E., Hancock, K.P., Daquin, J.C. & Kelly, K.S. (2023). The intersection of disability and race/ethnicity on victimization risk. Journal of Ethnicity in Criminal Justice, 21(1), 27-55. View

Daigle, L. E., Maher, C. A., Hayes, B. E., & Muñoz, R. B. (2024). Victimization, disability status, and fear among U.S. college students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 39(7/8), 1519–1542.View

Thompson, A., & Tapp, S. N., (2023). Criminal Victimization. BJS Bulletins.View

Harrell, E. (2017). Crime against Persons with Disabilities 2009-2015: Statistical Tables. U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.bjs. gov /index.cfm?ty=phdetailandid=586.View

Chadee, D., & Ying, N. K. (2013). Predictors of fear of crime: General fear versus perceived risk.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 43 (9): 1896–1904. doi:10.1111/jasp.12207.View

Collins, R. E. (2016). Addressing the inconsistencies in fear of crime research: A meta-analytic review.” Journal of Criminal Justice, 47 (December): 21–31.View

Felson, M., 2002. Crime and Everyday Life (3rd edition). Sage Publishing.View

Ferraro, K. F. (1995). Fear of Crime: Interpreting Victimization Risk. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. View

Franklin, C. A., & Franklin, T.W., (2009). Predicting Fear of Crime: Considering Differences Across Gender. Feminist Criminology 4(1):83-106.View

Cossman, J. S., & Rader, N. E. (2011). Fear of crime and personal vulnerability: Examining self-reported health. Sociological Spectrum, 31(2), 141–162. https:// doi.org/10.1080/02732173. 2011.541339View

Cossman, J. S., Porter, J. R., & Rader, N. E. (2016). Examining the effects of health in explaining fear of crime: A multi dimensional and multi-level analysis. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 41, 565–582.View

Ferraro, K. F. (1996). Women’s fear of victimization: Shadow of sexual assault? Social Forces, 75(2): 667. View

Steinmetz, N., & Austin, D. (2014). Fear of criminal victimization on a college campus: A visual and survey analysis of location and demographic factors. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 39(3): 511–37.View

Boateng, F. D., & Adjukum-Boateng, N. S., (2017). Differential Perceptions of Fear of Crime among College Students: The Race Factor. Journal of Ethnicity in Criminal Justice 15(2):00 00.View

Crowl, J. N., & Battin, J. R. (2017). Fear of crime and the police: Exploring lifestyle and individual determinants among university students. Police Journal, 90(3): 195–214. View

Fisher, B. S. (1995). Crime and fear on campus. Annals of the American Academy Of Political and Social Science, 539(5), 85 101.View

Daigle, L. E., Hancock, K., Chafin, T. C., & Azimi, A. (2022). US and Canadian college students’ fear of crime: A comparative investigation of fear of crime and its correlates. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(15–16), NP12901-NP12932.View

Pyo, J, & Haeysm, B. E. (2023). Assessment of functional and dysfunctional perceived threat of hate crimes among persons with and without disabilities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 38(23-24): 12135-12160.View

Warr, M. (2000). Fear of crime in the United States: Avenues for research and Policy. Measurement and analysis of crime and justice: Criminal Justice 2000 (David Duffee, Ed.) (pp.451 489). Washington, DC: US Department of Justice.View

Ferraro, K., F., & LaGrange, R. (1987). The measurement of fear of crime. Sociological Inquiry, 57(1), 70-101.View

Fisher, B. S., & Sloan, J. J. (2003). Unraveling the fear of victimization among college women: Is the shadow of sexual assault hypothesis supported. Justice Quarterly, 20(3): 633–60.View

Wilcox, P., Jordan, C. E., & Pritchard, A. J. (2006). Fear of acquaintance versus stranger rape as a ‘master status’: Towards refinement of the ‘shadow of sexual assault.’ Violence and Victims, 21(3): 355–70.View

Fisher, B. S., Sloan, J.J., & Wilkins, D. L. (1995). Fear of crime and perceived risk of victimization in an urban university setting. Campus Crime: Legal, Social, and Policy Perspectives (B, S. Fisher & J. J. Sloan, Eds).View

Fisher, B. S., & Nasar, J. L. (1992). Fear of crime in relation to three exterior site features: Prospect, refuge, and escape. Environment and Behavior, 24(1): 35–65. View

Fox, K. A., Nobles, M. R., & Piquero, A. R. (2009). Gender, crime victimization and fear of crime. Security Journal, 22(1): 24.View

Wilcox, P., Jordan, C. E., & Pritchard, A. J ., (2007). A multidimensional examination of campus safety: Victimization, perceptions of danger, worry about crime, and precautionary behavior among college women in the post-Clery era.” Crime and Delinquency, 53(2): 219–54.View

Brown, K. R., Peña, E. V., & Rankin, S. (2017). Unwanted sexual contact: Students with autism and other disabilities at greater risk. Journal of College Student Development, 58(5), 771–776. View

Scherer, H. L., Snyder, J. A., & Fisher, B. (2020). Intimate partner victimization among college students with and without disabilities: Prevalence of and relationship to emotional well-being. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 31(1): 49–80. doi:10.1177/0886260514555126.View

Midwestern State University (n.d.). Office of Disability Services (ODS): Physical support.View

Midwestern State University (n. d.). Office of Disability Services (ODS): Personal Assistance station. https://www.Midwestern. edu/student-affairs/health-and-wellness/disability-services/ personal-assistance-stationView

National Institutes of Health (2023). Mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic.View

Beadle-Brown, J., Richardson, L., Guest, C., Malovic, A., Bradshaw, J., & Himmerich, J. (2014). Living in fear: Better outcomes for people with learning disabilities and autism. Canterbury, UK: Tizard Centre, University of Kent.View

Keith, S. (2018). How do traditional bullying and cyberbullying victimization affect fear and coping among students? An application of general strain theory. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 43(1), 67–84.View

Pinquart, M. (2017). Systematic review: Bullying involvement of children with and without chronic physical illness and/or physical/sensory disability: Meta-Analytic comparison with healthy/nondisabled peers. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 42(3): 245–59.View

Hall, E. (2019). A geography of disability hate crime. Area, 51(2):249-256.View

Stopbullying.gov (n. d.). Bullying and children and youth with disabilities and special health needs. Retrieved from09/ bullyingtipsheet.pdfView

Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. 2014a. Comparing offending by adults and juveniles: What time of day are adults and juveniles most likely to commit violent crimes? Retrieved from: https://www.ojjdp.gov/ojstatbb/offenders/ qa03401.asp?qaDate=2010View

Olkin, R., Hayward, H., Abbene, M. S., & VanHeel, G. (2019). The experiences of microaggressions against women with visible and invisible disabilities. Journal of Social Issues, 73(3): 757–85.View

Covington, J., & Taylor, R. B. (1991). Fear of crime in urban residential neighborhoods: Implications of between- and within neighborhood sources for current models. The Sociological Quarterly, 32(2): 231. View

Gainey, R., Alper, M., & Chappell, A. T. (2011). Fear of crime revisited: Examining the direct and indirect effects of disorder, risk perception, and social capital. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 36(2): 120–37.View