Journal of Social Work and Welfare Policy vol. 2 iss. 1 (2024), Article ID: JSWWP-119

https://doi.org/10.33790/jswwp1100119Research Article

Grit, Social Support, and Academic Success of Youth Formerly in Foster Care

Erin Stevenson1* and Stephanie Saulnier2

Eastern Kentucky University, 521 Lancaster Ave., Keith Building, Richmond, KY, 40475, USA.

Corresponding Author Details: Erin Stevenson, Associate Professor, Department of Social Work, Eastern Kentucky University, 521 Lancaster Ave., Keith Building, Richmond, KY, 40475, USA.

Received date: 28th June, 2024

Accepted date: 29th July, 2024

Published date: 31st July, 2024

Citation: Stevenson, E., & Saulnier, S., (2024). Grit, Social Support, and Academic Success of Youth Formerly in Foster Care. J Soci Work Welf Policy, 2(2): 119.

Copyright: ©2024, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Abstract

Youth formerly in foster care (YFFC) often face relational and educational challenges due to their experiences in care. To explore these issues, undergraduates at a 4-year university completed an anonymous survey about their experiences with social support, resilience or grit, and academic challenges. The sample included 47 YFFC student respondents. Compared to other students, YFFC were more likely to be single parents, financially responsible for their family, and to experience very high stress levels. Greater grit and social support ratings were related to higher GPAs among all students, not just YFFC. Recommendations include collaboration between social workers and educators to provide resources that bolster relational and resilience skills for YFFC seeking a college degree.

Keywords: Resilience, Interpersonal Skills, College Students, Out of home care, Stress

Introduction

The transition from high school to college can be daunting for most students but for youth formerly in foster care (YFFC), the challenges can be overwhelming. YFFC include individuals who aged out of the foster care system or spent a significant amount of their childhood in foster care. The foster care system works to provide stability for children whose parents are unable to care for them, yet being in foster care increases the likelihood of experiencing adverse childhood events (ACEs) such as abuse, neglect, multiple placements, and disrupted relationships. These experiences can have long-lasting socio-emotional effects that can create barriers to higher education. These might be academic, personal, or financial challenges like navigating governmental hurdles to access waivers and financial support [1].

Purpose of the Study

There is a need for greater understanding of the strengths of YFFC and the areas where they may benefit from support in order to succeed academically [2]. More information about the specific barriers to retention and graduation experienced by YFFC can result in more effective institutional supports [3]. Without a solid academic background, YFFC are less likely to complete a degree [4] which may have a direct negative impact on employment opportunities and financial stability as an adult [5]. A better understanding of the traits most related to academic retention and success will help us plan better ways to bolster those among YFFC. To gain insight into characteristics that may be helpful for YFFC to succeed in college, researchers explored YFFC ratings of grit, social support, and student grade point average (GPAs) compared with non-YFFC students.

Literature Review

Research consistently shows that college students who have been in foster care have lower performance, retention, and graduation rates compared to the general population of students. In fact, YFFC are less likely to attempt college, and if they do, they are less likely to graduate from college than any other high-risk population [4]. About 10% of foster care youth are estimated to enroll in college but only about 3% to 5% graduate with a bachelor’s degree [6]. Meta-analysis of research shows several key factors related to these poor outcomes: academic difficulties, insufficient financial aid and housing, and the need for more socioemotional support [7,8,9]. Okpych & Courtney reported that economic issues, including the need to work full-time, and being a parent were significant barriers to degree completion by YFFC [3].

Ongoing mental health issues are also a concern, especially as youth aging out of foster care are much less likely to receive mental health services and are at higher risk of substance use as a form of self-medicating [10,11]. A lack of emotional and social support plays a role, as only 34% of those who aged out of care reported having a long-term significant relationship with an adult mentor [10]. Such supportive relationships with adults are often necessary to build social connections that can help them succeed in all life domains, including higher education. In this article, we explore how social support and grit may be predictors of better academic outcomes for YFFC.

Social Support

Having a mentor or caring adult in a child’s life, either at home, school or in the community, can function as a protective factor and increase positive connections with others [12]. In fact, high school dropout rates decrease with adult mentorship [13] and youth are better able to face challenges and overcome difficulties in school [6]. Interviewing foster youth transitioning out of care, Blakeslee and Best examined patterns in networks of social connections for these youth [14]. Strong, stable networks were linked to a wider range of connections with adults and mentors. Interpersonal skill deficits were cited by youth as a limitation in their ability to connect with others. These deficits arise from shifting family and home placements, lack of reliable case worker support, and self-reliance instead of asking for help when needed.

Interpersonal connections can aid youth in learning to access formal and informal resources which in turn help youth develop skills that allow them to persist at challenging tasks and reach out for help when needed [15]. Pincince examined the link between academic success as measured by a student’s grade point average (GPA) and relationships that support a person’s feeling of belonging. Results showed that informal social support, such as taking classes with friends and being involved in extracurricular activities, was related to higher GPAs among students [16].

Further exploring the concept that social support is important to academic success, Orpana and colleagues validated a 10-item Social Provisions Scale (SPS-10) focused on perceived social support [17]. They found this scale accurately measures an individual’s sense of connectedness which is a key element in positive well-being and achievement of goals [18]. Specific types of support include a sense of attachment or connection, guidance, social integration, trust through reliable alliances, and support that provides reassurance of worth. This scale could be a useful tool for social workers or academic advisors to examine young adults' connections to others and to focus on building support as needed.

For YFFC, social support often comes from the same sources as other high-risk college students, namely birth or foster families, peers, and adults who have served as mentors [19]. Unlike other students, YFFC’ relationships with family are often strained or inconsistent. The same can be true of relationships with professional supporters for YFFC such as social workers and case managers, as well as academic advisors, professors, and university staff [20]. When formal supports are lacking, YFFC rely on friends and peers to provide advice, information and at times, material support. However, the ability to form close and long-lasting relationships is often negatively impacted by placement instability and tenuous relationships with caregivers [21]. While these relationships can help YFFC navigate the academic and financial challenges, past negative experiences can lead to resistance in seeking support or refusing offered help [1].

In a recent study interviewing youth aging out of foster care about resources they needed, almost three-fourths (72%) of youth highlighted the need for adults who support them by listening and being non-judgmental [22]. The surveyed youth shared the feeling that adults often assumed they knew what foster care was like for them instead of getting to know them as individuals with unique needs and perspectives. This can exacerbate the lack of trust in authority figures. When asked about social support needs, foster youth wished for adults who are willing to just listen, encourage them to learn ways to self-regulate big emotions and provide guidance when asked [23]. Katz and Geiger found that formal supports available to YFFC in high school tended to drop off when entering college, leaving youth to rely on more informal supports such as friends, peers, and coworkers/supervisors [21]. Youth in that study remarked that the supportive relationships were “versatile, long-term, unconditional, non-judgmental and trusting” [[21], pg. 156]. As YFFC are less likely to have extensive social support networks, they are often left to navigate new situations on their own.

We also know foster care youth have many strengths, are resilient, and often work through obstacles alone rather than seek support in school which can be both a limitation and an asset [2]. For example, youth who enter college with more support are more likely to persevere to graduation [19]. YFFC are more at risk of dropping out if they do not feel like they have people that can help them surmount the various hurdles of financial aid, registering for classes, or buying books [21,24]. Students who feel supported and connected, especially with staff and faculty in the college setting, are more likely to persevere, particularly beyond their first year [19]. Different types of social support serve different purposes and collectively can significantly improve outcomes. For example, informational support can help YFFC navigate financial obstacles such as applying for aid. Instrumental support can provide tangible aid like emergency money or a place to stay during school breaks [1].

Grit

The term “grit” has been used to describe a person’s ability to persist with tasks and the willingness to continue to act toward goals despite challenges. YFFC often struggle with access to academic and financial resources or with interpersonal skills needed to succeed in college [7,8,9]. Learning to persist and finding the inner strength to overcome barriers is a skill YFFC may have developed due to their life circumstances. Duckworth et al. created a scale to measure a person’s level of grit as a construct and found their scale more accurately predicted achievement in academic domains than talent or skill [25]. This is because grit includes the ability to sustain effort and focus on a goal over time [25]. Almeida et al. used social network analysis to compare the impact of grit versus social resources on academic success and found that social resources measured as formal and informal support in relationships with peers and professors at the university were even more predictive of success than grit levels [26]. Grit among YFFC does not appear to be addressed in the research literature and may be a useful variable to explore.

Materials and Methods

This exploratory study focused on characteristics that may be related to academic achievement, such as grit and social support, among a sample of undergraduate college students at a southeastern 4-year public university. The university is located in the Appalachian region and has a large population of first-generation students. The study used a convenience sample of students. The university’s Office of Institutional Research (IOR) pulled a list of currently enrolled full time undergraduate students ages 18-29 from the university registrar. The IOR emailed an invitation to all eligible students that included a link to the anonymous online survey. The researchers did not have access to any identifying information. The survey was conducted in Spring 2022 and approved as an exempt study by the university’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) as protocol #2846. Consent was implied by reading the introduction script to the online survey and agreeing to participate by continuing to the next screen to start the survey questions. Participants were instructed they could stop at any time and quit the survey by exiting the screen.

Participants were offered the opportunity to be included in a raffle for 50 participants to win a $10 Amazon.com gift card. A new window opened after the survey responses were recorded allowing students to add an email address to enter the raffle. Participants were informed their email address was separate from the survey responses with no connection between them. The email was only used to alert randomly selected winners after the survey closed.

Measures

Survey questions included the validated 8-item 5-point Likert-style Grit-S scale [27] to measure focus on tasks and ability to persist toward goals despite challenges. The validated 10-item 4-point Likert-style Social Provisions Scale (SPS-10) was also included to measure perceived social support among respondents [28]. The measure for academic success was a self-reported grade point average (GPA) in the student’s major. Several questions were also asked about student’s confidence in academics and their future academic plans.

Since this was an anonymous survey, we were not able to evaluate other more formal academic success factors matched with the sample (See Appendix 1 for the full survey.). The survey also asked students to self-report if they had ever been in foster care as a child. There are many layers to foster care experiences that are complicated to examine. This exploratory study used the yes/no variable as an indicator that foster care was a childhood experience that touched this participant’s life in some way. Though the self-reported measures are simplistic in relation to overly complex topics, the limitations of an anonymous survey precluded other options.

Results

Sample

The researchers decided to exclude surveys that were less than 75% complete, resulting in a final sample of 1,040 completed surveys. The survey invitation was sent by the university’s Institutional Office of Research (IOR) to 8,206 full-time undergraduate students who met the inclusion criteria, yielding a response rate of 12.7%. Data analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS software version 19. Data analysis included frequencies, crosstabulations, and t-tests to compare responses between YFFC and non-YFFC students. Significance testing used a cutoff p-value of .05. A regression model was employed to examine the potential impact of grit, social support, and YFFC status on GPA. Comparisons between respondents’ groups are provided here and in tables with YFFC percentages listed first followed by non-YFFC responses to reduce repetition of terms.

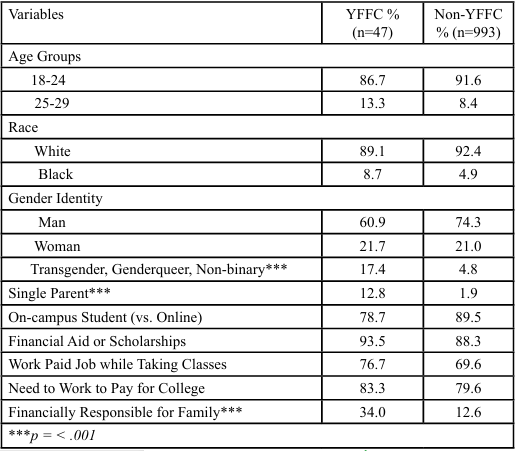

Among the sample, 4.5% (n=47) self-identified as YFFC (See Table 1). Most of the sample comparing YFFC with non-YFFC respondents were white (89.1 vs. 92.4%) or black (8.7 vs. 4.9%) and ages 18- 24 years old (86.7 vs. 91.6%) or 25-29 years old (13.3 vs. 8.4%). Being ages 18-29 was part of eligibility criteria; age responses were grouped rather than collected as individual ages. Examining gender identity, most respondents identified as women (60.9 vs. 74.3%) or as men (21.7 vs. 21.0%). More YFFC (17.4%) than non-YFFC (1.9%) identified as non-binary, transgender, or genderqueer (p = <.001).

The majority of respondents took classes on campus as opposed to online (78.7 vs. 89.5%) and had entered the university as first time college students (61.7 vs. 70.1%).). No individual class data was collected (i.e., first year student, second year). Over 65 different majors were represented in this sample (26 majors just among YFFC) with 22 students who were undecided at the time of the survey. The average GPA in their major area of study was lower for YFFC (M = 3.1, SD = 0.7) than non-YFFC students (M = 3.4, SD = 0.5, p = < 001). [Not in table]

Most students had scholarships or financial aid to help pay for college tuition (93.5 vs. 88.3%). Youth who aged out of foster care or were adopted from foster care may be eligible to use a state-specific waiver for tuition and 21.3% of YFFC reported using this option. The majority of both YFFC and non-YFFC students worked at a paid job while taking classes (76.7 vs. 69.6%) and needed to work to pay for college and living expenses (83.3 vs. 79.6%). More YFFC students (12.8%) were single parents than non-YFFC (1.9%, p = < .001). Additionally, more YFFC (34.0%) were financially responsible for other family members compared to non-YFFC (12.6%, p = <.001). When asked to rate their current levels of stress with balancing work, life, and school two-thirds (66.0%) of YFFC and over half (50.8%) of non-YFFC indicated very high stress levels (p = .032).

Foster Care Youth

Participants self-reported if they had spent any time in foster care as a child. Among these individuals, their average number of placements as a child ranged from 1-13 (M = 2, SD = 2). On average they spent about 5.5 years in care (SD = 5.5). Almost half of YFFC (48.9%) described being raised in a single parent household during middle and high school and 46.8% were the oldest child in the family. Asked about the outcome of their time in foster care, 44.4% were reunited with their parents, 26.7% were adopted, and 28.9% aged out of foster care.Social Support

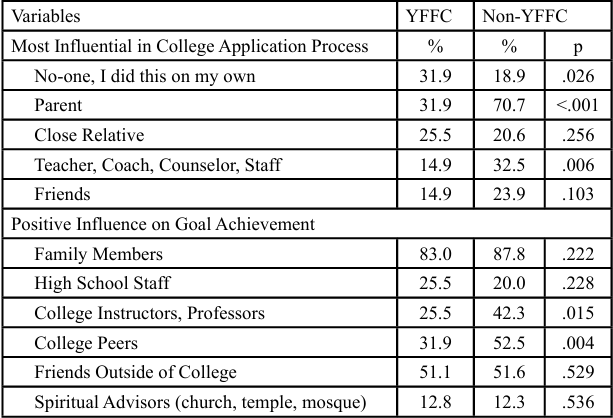

Social connectedness questions asked participants to think about who was most influential in helping with their college applications (See Table 2). More YFFC reported that no-one had helped them apply to college and that they had gone through this process by themselves (31.9 vs. 18.9%, p = < .026). Fewer YFFC than non-YFFC (31.9 vs. 70.7%, p = < .001) had parental assistance or help from teachers, coaches, counselors, or school staff (14.9 vs 32.5%, p = .006).

Respondents were also asked who currently in their life has a positive influence on their academic goal achievement. They could choose multiple responses. The majority of YFFC (83.0%) and non-YFFC respondents (87.8%) pointed to family members. Just over half (51.1 vs. 51.6%) noted that friends outside of college had a positive influence. Positive support from their college peers was selected by fewer YFFC than non-YFFC (31.9 vs. 52.5%, p = .004). The same held true for a positive influence on their goal achievement from college instructors or professors (25.5 vs. 42.3%, p = .015).

Support can also come from within oneself and is often measured as self-confidence levels [not in table]. Respondents were asked to rate their ability to complete a degree from not at all confident to very confident. Just over half of YFFC (53.2%) were very confident they would complete their degree compared to over three-fourths of non-YFFC (78.4%, p = < .001). Just under half of YFFC and just over half of non-YFFC were very confident they would achieve their academic goals (42.6 vs. 57.1%). A similar percentage of both groups were moderately satisfied with their academic careers (40.4 vs. 44.2%) and slightly more YFFC planned to attend graduate school after completing their bachelor’s degree (53.2 vs. 46.0%).

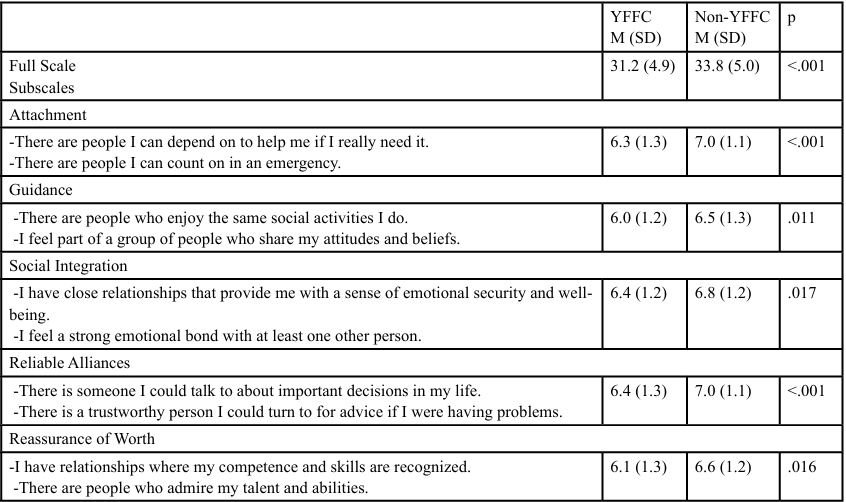

Social Provisions Scale (SPS-10)

The SPS-10 measures perceived support from other people in your social network with responses to statements ranging from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’. Scores are tallied for each of the ten questions with the highest possible score as 40 (very high support) and the lowest at 10 (very low support). YFFC average scores indicated lower social support (M = 31.2, SD = 4.9) than non–YFFC students (M = 33.8, SD = 5.0, p = < .001).

Grit-S Scale

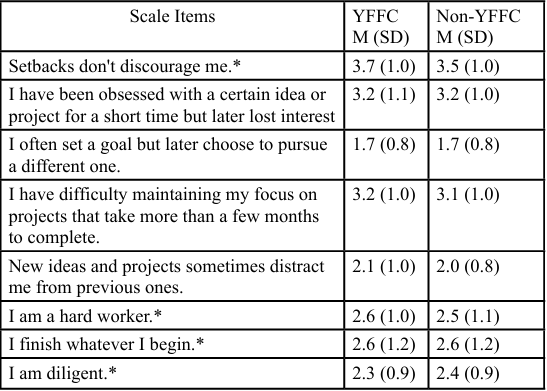

The Grit-S scale includes 8 questions with responses ranging from ‘very much like me’ to ‘not like me at all’. The list of questions and responses are provided in Table 4. After reverse scoring appropriate items, a tallied score was computed with a possible range of 8-40 points. Average scores were similar for YFFC (M = 21.5, SD = 2.9) and non-YFFC (M = 20.9, SD = 2.7).

Regression

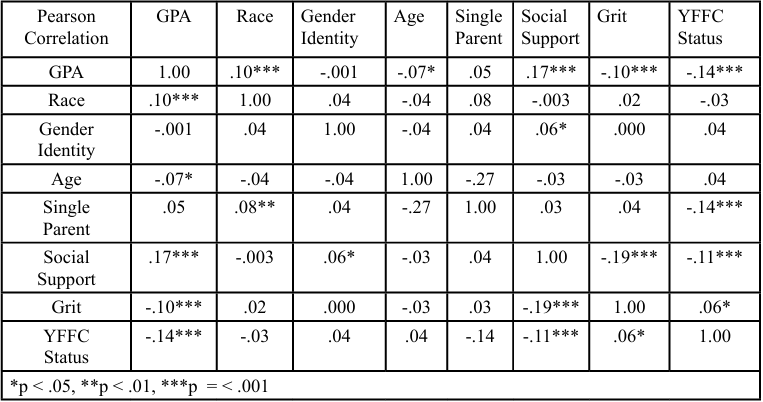

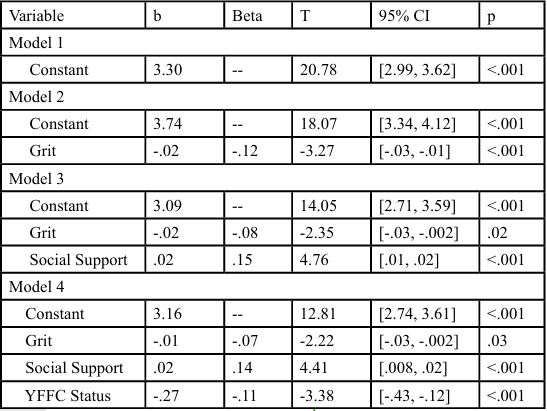

A linear regression model was created to examine the relationship between the dependent variable of GPA with the predictor variables of grit, social support, and YFFC status. Control variables were entered first including gender identity (man, woman, transgender/ nonbinary/ genderqueer), race (white, other), age group (18-24 or 25-29), and single parent status (yes, no, no children). The second model added social provisions scale scores. The third model added grit scale scores. The fourth model added experience in foster care status (yes/no).

Results of the regression model are displayed in Table 6. The R2 values incrementally increase in each model and reflect how much variance in GPA could be related to each predictor variable (i.e., grit, social support, YFFC status). This means as we add each independent variable into our model there is slightly more variation in GPA. Model 2 enters grit scores as the predictor variable. This reflects a 16% increase in GPA. Model 3 adds social support scores which increases the variance to 22%. Model 4 includes YFFC status as a predictor and this increases the explained variance in GPA to 25%.

Each model is statistically significant showing a good fit with the terms. The regression model indicated social support, grit and YFFC status could help explain 25% of the variance in GPAs. Together as a group these variables appear to influence GPA more than individually. With the small variance represented in this model, it would be beneficial to find a more robust measure of academic achievement to include in future studies, as well as a greater sample of YFFC. Adding specific data from academic records for example could help provide more insight.

Discussion

The data from this study found similar levels of resilience measured as grit scores between both groups of students, though YFFC had significantly lower GPAs and social support levels. The data also reflect possible connections between grit, social support, and increased GPAs. This was a very small pilot study sample of YFFC, but it hints at the importance of improving interpersonal skills to support positive relationships. These are skills that can be learned and improved with practice. Exploring the impact of providing YFFC with interpersonal skills training to see if there are beneficial increases in grit and social support is recommended. Building relational and emotional coping skills as well as grit to persist with the difficulties of college might prove an essential part of supporting YFFC as they transition from care to living as a young adult at college.

Another area of interest from this sample of students is youth who identify as LGBTQIA, particularly non-binary, genderqueer, or transgender. Best practices for supporting this community of youth should be specifically included in foster care provider education. Our survey found a small but significantly greater percentage of YFFC identifying as non-binary, genderqueer, or transgender. The stigma and socioemotional challenges faced by this population can add barriers for them when facing the development of positive relationships with others to support their efforts at earning a college degree. The U.S. Children’s Bureau compiled information for foster parents focusing on gender identity and supportive parenting techniques [29] These are resources for college administrators, faculty, staff, and mentors to continue to build the support for YFFC youth and provide a safe haven for them in the educational community. Realizing there may be more non-binary and transgender students in the YFFC population than acknowledged in our small sample is important because we know the overlap between these populations renders them doubly at-risk of struggling in college without proper guidance and support [30].

A very small portion, less than one-fourth, of the YFFC in this sample reported using the state tuition waiver that may be available to them. The state where this study took place provides a tuition waiver for youth who have ever been in the foster care system even if they were adopted. This waiver covers the cost of tuition and mandatory fees at all the state’s public universities and community and technical colleges [31]. The waiver must be used within four years of graduating high school or obtaining a GED and once utilized, the waiver is good for 5 years. This finding is particularly relevant as economic hardships have been linked to significantly reduced retention and graduation rates for this population [1]. In theory, more of the students in the survey that reported aging out or being adopted out of foster care may qualify for tuition help. While there may be various reasons why the students may not have used the state tuition waiver, financial support is an important indicator in college success. The authors are doing further research that will investigate YFFC’s knowledge about and willingness to pursue the use of the state waiver program. It is important that colleges and universities reach out to the incoming YFFC population to share information about this option and support students in navigating access to additional financial resources such as books and supplies. Without understanding the best ways to pay for college, students may be taking on greater loans or financial stressors than necessary. Helping students make solid financial choices can have a positive long-term impact.

As noted earlier, this university is located in Appalachia, an area of the country with a higher percentage of poverty nationally. The university also has a significant population of non-traditional students (i.e., student parents). YFFC were most likely to fit this profile as single parents and financial providers for their families while taking college courses. Though all respondents reported high stress levels with work/life/school balance, YFFC stress was significantly higher than the non-YFFC respondents. This may be due to additional responsibilities and challenges as parents and caregivers. How we address and respond to our young parents in the college environment should be examined with particular focus on YFFC who have fewer role models for both academic success and parenting. Connecting these students to resources or support could impact their ability to earn a college degree and future family stability. Additionally, foster care providers and case managers should be encouraged to talk with foster youth about the possibility of enrolling in college. Coordinated support as youth transition from foster care should include mental health and education planning resources [11]. This study highlighted the fact that almost one-third of YFFC completed the college application process on their own without assistance. They reported limited connections with faculty, staff, or college peers and more reliance on social support from friends and family outside of the university. Making links with campus resources can increase the likelihood of academic success.

Limitations

There are several limitations in the current study that should be acknowledged. First, the response rate was 12.7%, thus students who did not participate in the survey may be significantly different than the study sample. We know from extant literature that YFFC have a higher drop-out rate than non-YFFC. This could mean the sample in our study represents only the small number of YFFC who stayed in college. It is important to also note this study is exploratory and does not address deeper layers that might be found with a wider sample and a greater number of relevant variables. Ideally, there would be a greater number of students included with foster care system experiences to increase the odds of accurately representing their perspectives. Social network analysis would be an excellent way to further examine more details surrounding relationships and connectedness among YFFC before and after college.

Involvement with the foster care system can vary widely for each person depending on factors such as adverse childhood events, the length of time in care, and outcome of the involvement. For this study, we were not able to go into detail about foster care background. We share average number of placements and length of time in care as self-report. Future studies would benefit from elaborating on experiences in care and the impact on academic achievement. The trauma of any removal and placement leaves an impact on the child. This study has promising indicators that need further investigation with a more rigorous research design.

GPA is one commonly used measure of academic achievement, but we know that achievement is more nuanced than one cumulative score. Ideally, measurement would include more specific details from official records. Unfortunately, linking respondent information with institutional data was not a feasible option in this study. We suggest future studies examine respondents' official transcripts or examine more longitudinal measures of academic success to better understand potential relationships.

Implications for Practice and Policy

This research study explores the relationship between grit and social support as it relates to academic success among college students, particularly YFFC. Results suggest there may be an interwoven relationship between personal levels of grit and perception of social support that is worth exploring. Students with grit or the ability to persist through challenges and the skills to connect with others who can encourage educational progress may have more success academically than those without these skills. These skills can be taught and as we better grasp their importance in education, adults who support and work with YFFC should be encouraged to help them develop these resiliency skills.

Though this research study is merely an initial exploration of characteristics like grit and connectedness to social supports for YFFC, there are several takeaways we suggest educators and social workers consider.

1. Expanding awareness of, and access to, the state or federal tuition waivers available for foster and adoptive youth. As of 2021, 24 states had statewide tuition waivers and a total of 31 had some type of statewide postsecondary education tuition waiver or scholarship program for YFFC. By increasing awareness of and accessibility to these financial supports, student success can be positively affected, and long-term stability increased by reducing the financial burden. This information should be provided to youth in high school by trusted professionals to allow adequate time for planning. While state child welfare agencies are already required to provide transition services to older youth in foster care and independent living, policies can be strengthened to ensure youth are aware of their options and have assistance through the process of applying for college and financial aid.

2.Identifying and providing stronger campus-based support connections for YFFC. There is a need to support YFFC who are single parents and who are financially supporting family members while trying to attend college. There are models of campus-based programs in more than 30 states providing valuable resources for colleges and universities that are focused on improving in these areas [3]. This might also include teaching interpersonal skills that help to build and maintain positive relationships. Mentoring is one way to build relational skills. At our university, a pilot program linking YFFC with graduate students in Social Work, Psychology and Mental Health Counseling has shown positive outcomes in its pilot phase. The term “interdependent” care has been used to indicate the ongoing social support for youth transitioning out of foster care to aid in developing interpersonal skills and positive relationships [32].

3. In our data, there were a significant number of YFFC who identified as LGBTQIA. This population already faces socioemotional hurdles. It is incumbent upon schools at all levels to incorporate support for students to safely express their unique strengths and personalities while achieving their academic goals. The Inclusive Schools Network offers guided resources for school professionals and families to learn about the variety of gender expressions and best practices for supporting LGBTQIA identified youth [30].

Conclusion

Post-secondary education is essential to gainful employment and the stability to maintain a household and family. We have identified additional hurdles encountered by YFFC as they pursue higher education. By adding more pre-enrollment and campus based resources to mentor YFFC on building resilience, coping, and interpersonal skills, the odds YFFC can succeed will increase. Future research is encouraged to expand our knowledge of this unique population and the support and resources that provide the best opportunity for academic success.

Competing Interests:

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to the Eastern Kentucky University’s Data Initiatives Team at the Noel Studio for their help with the results section.

References

Okpych, N.J. & Gray, L.A. (2021). Ties that bond and bridge: exploring social capital among college students with foster care histories using a novel social network instrument (FC Connects). Innovative Higher Education, 46, 683-705. View

Kothari, B.H., Godlewski, B., Lipscomb, S.T., & Jaramillo, J. (2021). Educational resilience among youth in foster care. Psychology in Schools, 58, 913–934.View

Okpych, N. J. & Courtney, M. E. (2023). When foster youth go to college: Assessing barriers and supports to degree completion for college students with foster care histories. IRP Focus on Poverty, 39(1), 1-6. View

Day, A., Dworsky, A., & Feng, W. (2013). An analysis of foster care placement history and post-secondary graduation rates. Research in Higher Education Journal, 19, 1–17.View

Abel, J.R., & Deitz, R. (2014). Do the benefits of college still outweigh the costs? Federal Reserve Bank of New York: Current Issues in Economics and Finance, 20(3), 1-12.View

Geiger, J.M. & Beltran, S.J. (2017). Readiness, access, preparation, and support for foster care alumni in higher education: A review of the literature. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 11(45), 487–515.View

Gillum, N.L., Lindsay, T. Murray, F.L., & Wells, P. (2016). A review of research on college educational outcomes of students who experienced foster care. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 10(3), 291-309.View

Huang, H., Fernandez, S., Rhoden, M.A. & Joseph, R. (2018). Serving former foster youth and homeless students in college. Journal of Social Service Research, 44(2), 209-222.View

Randolph, K.A., & Thompson, H. (2017). A systematic review of interventions to improve post-secondary educational outcomes among foster care alumni. Children and Youth Services Review, 79, 602-611.View

Geiger, J.M., Piel, M.H., Day, A., & Schelbe, L. (2018). A descriptive analysis of programs serving foster care alumni in higher education: Challenges and opportunities. Children and Youth Services Review, 85, 287-294.View

White, C.R., O’Brien, K., Pecora, P.J., & Buher, A. (2015). Mental health and educational outcomes for youth transitioning from foster care in Michigan. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 96(1), 3-75. View

Okpych, N.J., & Courtney, M.E. (2017). Who goes to college? Social capital and other predictors of college enrollment for foster-care youth. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 8(4), 563-593.View

Lee, V.E., & Burkham, D.T. (2003). Dropping out of high school: The role of school organization and structure. American Educational Research Journal - Summer, 40(2), 353–393. View

Blakeslee, J.E., & Best, J.I. (2019). Understanding support network capacity during the transition from foster care: Youth identified barriers, facilitators, and enhancement strategies. Child Services Review, 96, 220–230.View

Murphey, D., Bandy, T., Schmitz, H., & Moore, K.A. (2013). Caring adults: Important for positive child well-being. Child Trends Research Brief, Publication #2013-54.View

Pincince, M. (2020). Effects of social capital on student academic performance. Perspectives, 12(3), 1-15. View

Orpana, H.M., Lang, J.J., & Yurkowski, K. (2019). Validation of a brief version of the Social Provisions Scale using Canadian national survey data. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention Canada, 39(12), 323-332. https://doi.org/10.24095/ hpcdp.39.12.02 View

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDCP). (2009). School connectedness: Strategies for increasing protective factors among youth. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/protective/youth connectedness-important-protective-factor-for-health-well being.htmView

Franco, J., & Durdella, N. (2018). The influence of social and family backgrounds on college transition experiences of foster youth. New Directions for Community Colleges, 181, 69-80. View

Salazar, A.M. (2012). Supporting college success in foster care alumni. Child Welfare, 91(5), 139-168. View

Katz, C.C., & Geiger, J.M. (2019). ‘We need that person that doesn’t give up on us’: The role of social support in the pursuit of post-secondary education for youth with foster care experience who are transition-aged. Child Welfare, 97(6), 145-164. https:// www.jstor.org/stable/48626320 View

Geiger, P.J., Aranguren, N., & Dolan, M.M. (2022). Recommendations for child welfare system support from youth currently and formerly in foster care. OPRE Report 2022-84. Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. View

Schroeter, M. K., Strolin-Goltzman, J., Suter, J., Werrbach, M., Hayden-West, K., Wilkins, Z., Gagon, M., & Rock, J. (2015). Foster youth perceptions on educational well-being. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 96(4), 227-233.View

Dumais, S. A., & Spence, N. J. (2021). ‘There’s just a certain armor that you have to put on.’ Child Welfare, 99(2), 135-156. View

Duckworth, A.L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M.D., & Kelly, D.R. (2007). Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92,1087–1101. View

Almeida, D.J., Byrne, A.M., Smith, R.M., & Ruiz, S. (2021). How relevant is grit? The importance of social capital in first generation college students’ academic success. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory and Practice, 23(3), 539-559.View

Duckworth, A.L., & Quinn, P.D. (2009). Development and validation of the short grit scale (Grit-S). Journal of Personality Assessment, 91(2), 166-174. View

Okpych, N. & Courtney, M. (2019). Longitudinal analyses of educational outcomes for youth transitioning out of care in the US: Trends and influential factors. Oxford Review of Education, 45(4), 461-480. View

Child Welfare Information Gateway. (2021). Supporting LGBTQ+ youth: A guide for foster parents. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Children's Bureau. View

Gender Spectrum. (2019). Inclusive schools network: Information guide. Gender Spectrum. https://www. genderspectrum.org/articles/inclusive-schools-networkView

Commonwealth of Kentucky (CoK). (2018). KY RISE: Education. https://prd.webapps.chfs.ky.gov/kyrise/ Home/Education#:~:text=Educational%20Training%20 Voucher,completing%20a%20job%2Dtraining%20program View

Antle, B.F., Johnson, L., Barbee, A., & Sullivan, D. (2009). Fostering interdependent versus independent living in youth aging out of care through healthy relationships. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 90(3), 243-342.View