Journal of Social Work and Welfare Policy Volume 3 (2025), Article ID: JSWWP-134

https://doi.org/10.33790/jswwp1100134Research Article

College Student Sexual Risk Taking Behaviors: Continuum of HIV Prevention Needed on College Campuses

Ali Salman1, Yi-Hui Lee2, Hyejin Kim3, Sarah E. Twill4*

1 School of Nursing, College of Health & Human Sciences, North Carolina A&T State University, Greensboro, NC, 27411, United States.

2 School of Nursing, Wright State University, Dayton, OH, 45435-0001, United States.

3,4 School of Social Work and Human Services, Wright State University, Dayton, Ohio 45435, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Sarah E. Twill, Ph.D, M.S.W., Professor, School of Social Work and Human Services, Wright State University, Dayton, Ohio 45435, United States.

Received date: 18th January, 2025

Accepted date: 20th February, 2025

Published date: 22nd February, 2025

Citation: Salman, A., Lee, Y. H., Kim, H., Twill, S. E., (2025). College Student Sexual Risk Taking Behaviors: Continuum of HIV Prevention Needed on College Campuses. J Soci Work Welf Policy, 3(1): 134.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Abstract

This cross-sectional study investigated the risky sexual behaviors of American college students, focusing on the associations between condom use practices and various risk factors including drinking before sex, history of non-injection drug use, hookup experiences, and one-night stands. Data collected from a total of 325 sexually active American college students recruited via a convenience sampling method was analyzed. This study revealed a significant association between inconsistent condom use and a history of drug use, alcohol consumption prior to sex, hooking up, and one-night stands. Participants who engaged in these behaviors were less likely to use condoms as a protective measure during sexual intercourse. These findings emphasize the need for enhanced sexual health education, campus-level interventions, and stronger partnerships between universities, community public health organizations, and policymakers. The study concludes by advocating for comprehensive sexual education programs, policy reforms, and advocacy efforts to reduce risky sexual behaviors and improve sexual health outcomes for college students.

Keywords: HIV Prevention; Risky Sexual Behaviors; Condom use; Substance Use; Hookups

Introduction

HIV impacts people across all age groups in the United States, but certain age ranges are disproportionately affected. In 2022, individuals aged 13 to 34 made up over 60% of estimated new HIV cases, and young people aged 13-24 account for 21% of new HIV infections annually [1]. The high incidence of HIV infections within younger demographic population underscores the vulnerability of this age group in the context of evolving sexual behaviors.

Risky Sexual Behaviors Among College Students

The majority of the college students in the U.S.A. are young adults aged 20 to 24 [2]. College students are at a critical life period of time transitioning to adulthood. During this phase of emerging adulthood, many of these young people begin living autonomously and making behavioral health choices without direct guidance of their parents [3]. Frequent engaging in many risky behaviors including risky sexual behaviors is common among college students [4,5]. Risky sexual behaviors, such as inconsistent condom use, engaging in casual sex, having multiple concurrent or overlapping partners, and having sex while under the influence of drugs or alcohol, increase one’s susceptibility to sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and are significant contributors to the risk of contracting HIV infection [6,7]. College students' engagement in risky behaviors and sexual practices significantly increases their vulnerability to unintended pregnancies as well as their risk of contracting HIV and other STIs [8].

College Students’ Hookups Behaviors and Sexual Risk-taking

The prevalent "hooking up" culture, which refers to short-term, casual, non-committed sexual encounters between individuals who are either strangers or casual acquaintances, is common among college students and young adults [9-13]. Studies on hookup culture highlight that social events involving alcohol and drug use play a pivotal role in facilitating sexual encounters among college students [9,10,13,14].

As hookups often occur in situations involving consuming alcohol [10], researchers found a link between alcohol use and hooking up among college students [10,15]. Research found that alcohol use was more commonly reported during sexual encounters with casual partners than with steady partners [16]. Increased alcohol consumption linked to a higher frequency of hooking up [10,15]. However, the strength of this association varies depending on whether alcohol consumption was measured globally over a general time period, within hookup situations, or during specific hookup events [10].

Drinking prior to hooking up was associated with meeting partners for the first time that night [17]. Furthermore, more female college students who consumed alcohol before hooking up reported feeling discontent with their hookup decisions (LaBrie et al., 2014). Also, alcohol use was more strongly associated with oral sex, while penetrative sex was influenced by other factors, such as current relationship status [18]. However, heavy alcohol use was associated with an increased likelihood of engaging in penetrative hookup experiences [19].

Literature showed that college students with higher alcohol use and more positive attitudes toward hooking up reported engaging in more hookup experiences [20]. Particularly, female students were less satisfied with their hookup decisions compared to male students [20]. Additionally, college students with high sexual sensation-seeking tendencies were more likely to engage in risky sexual behaviors, such as cybersex, multiple sexual partners, and one-night stands [21].

Substance Use And HIV Risk

Substance use is prevalent among college students [22-26]. Alcohol and cannabis use are the most highly prevalent substance used by college students [3,4,8,24,27,28]. Studies showed that most users of alcohol and cannabis are more likely to use them simultaneously [25,27].

Substance use and misuse including alcohol and other drugs is often associated with increased sexual risk [29]. It can impair judgment and decision-making, leading to behaviors such as unprotected sex and multiple sexual partners, which increase the risk of sexually transmitted infections and unintended pregnancies [30-35]. Substance use is a significant risk factor for HIV transmission, primarily through its association with sexual risk behaviors such as unprotected sex and multiple sexual partners [30].

A strong connection between alcohol consumption and sexual engagements exists among college students [4,32,33]. A recent meta-analysis of 50 studies found that alcohol consumption is a significant factor contributing to risky sexual behaviors, such as early sexual initiation, inconsistent condom use, and multiple sexual partners among adolescents and young adults [32]. Studies generally show a positive association between alcohol consumption and risky sexual behaviors; however, evidence on causation remains mixed across different populations and research methods. It was suggested that the relationship between alcohol and sexual risk behavior is influenced by situational factors, such as partner type and relationship duration should be considered when investigate the association between sexual risk behaviors and alcohol drinking behaviors among college students [4,36,37].

Cannabis (or marijuana) is the most used drug among college students [23,24,27,28,38]. Compared to studies on alcohol use, research on the influence of non-injection drug uses such as marijuana and inhaled nitrite on sexual behaviors is less extensive. However, previous studies indicate that marijuana users are more likely to engage in high-risk behaviors, including alcohol consumption and risky sexual activities [39]. Existing evidence indicates that marijuana users are more likely to engage in risky sexual activities and face a higher risk of STIs [27,37,39]. Researchers discovered that college students who used marijuana reported having more sexual partners and significantly less likely to use condoms during vaginal intercourse compared to those were non-users [27,39,40]. However, other studies reported that regular marijuana use did not predict condom use among college students, and no main effect of marijuana use on condom use was found [37]. While findings on condom use are mixed, most studies suggest that marijuana use is associated with reduced condom use frequency.

Condom Use Among College Students

Condom use is one of the most effective methods for preventing the transmission of HIV and other STIs [41]. When used consistently and correctly, condoms function as a barrier to block the exchange of bodily fluids during sexual activity, significantly reducing the risk of infection [41,42]. According to the American College Health Association [8], 46% of sexually active undergraduate students reported having vaginal sex in the past 30 days. However, only less than half of these students indicated they consistently used a condom or used one most of the time during these encounters within the same time frame [8]. This highlights a gap in protective behavior among students despite their frequent sexual activity.

Literature showed that relationship dynamics, perception of risk, and gender roles may influence college students’ decision related to condom use [43]. Studies found that college students and females in more committed relationships were also less likely to use condoms [18,44,45]. Research also showed that female and white students were less likely to use condoms during hookups. Conversely, students who were uncertain about or uninterested in a future romantic relationship with their hookup partners were more likely to use condoms [11]. Female students seeking romantic relationships with their hookup partners had lower rates of condom use during their last vaginal intercourse [11]. Relationship intentions may influence college students’ condom use during their hookup behaviors [11]. Additionally, previous studies reported that female and older college students were less likely to use condoms [19,46,47]. Other barriers to condom use include misconceptions and negative attitudes, lack of social support and self-efficacy, and insufficient action planning [48,49]. Moreover, previous studies have either not included condom use [20,21] or have examined condom use only as part of risky sexual behaviors [21,32,47]. Also, studies investigating factors affecting condom use often did not account for multiple risky sexual behaviors [46,48,50]. Additionally, many recent studies were conducted in countries where norms around sexual behavior, sexual health education, and risk management could differ from those in the U.S. [47-50].

Purpose of the Study

Given the importance of condom use among young adults in preventing STIs, including HIV, and the need for more up-to-date studies within the U.S., this study examines factors influencing college students’ risky sexual behaviors, with a particular focus on condom use. Specifically, drinking before sex, having history of non-injection drug use (e.g. Marijuana and inhaled nitrite, etc.)), having hooking up experiences, and one-night stands—were analyzed to explore their relationships with condom use among American college students in the U.S. This research aims to explore whether these behaviors influence condom use, providing insights into sexual health practices and risk factors within this population. The purpose of the study was (1) to describe the American college students’ risky sexual behaviors, and (2) to examine the associations between condom use practices and various risky behaviors including drinking before sex, history of non-injection drug use, hookup experiences, and one-night stands among American college students.

Materials and Methods

Study Design, Sampling and Sample

This cross-sectional designed study utilized a convenience sampling method to recruit undergraduate college students enrolled in a university located in Ohio, USA. College students who were 18 to 24 years old, able to speak and read English, and with no self-reported cognitive impairment or diagnosis of a major depressive disorder were eligible to participated in this study. Power analysis used to estimate the sample size for this study. Among 437 college students who completed the study questionnaires, 325 of them reported that they had sexual experiences.

Data Collection Procedure and Ethical Considerations

The institutional review board approval was obtained prior to approaching potential participants and for data collection. The researchers of this study contacted professors and/or course instructors to obtain permission for accessing their students and scheduling class visits. During class visits, students were provided with explanations regarding purposes of the study, inclusion and exclusion criteria, potential benefits, and risks, as well as confidentiality and anonymity measures. Students were also informed about their rights to withdraw at any time.

Students self-assessed their own eligibility to participate in the study based on the provided inclusion and exclusion criteria. Those who consented to participate completed the study questionnaires either in the classroom or in any other location where they felt comfortable. Participants either directly returned their completed questionnaires to the researchers by placing the questionnaires in provided envelopes/ collecting box or submitted them to a secure, locked drop box located on campus.

Measures and Instruments

Demographic and behavioral information sheet was used to collect demographic data and risky-taking behaviors. Demographic data such as age, gender and religion were collected to provide background information about the participants. Questions related to participants’ sexual experience, history of drinking alcohol, history of smoking cigarettes, history of using non-injection drug (e.g. Marijuana and inhaled nitrite, etc.), condom use practice, sexual partners, hooking up experience and so on were also asked to collect information about participants’ risky-taking behaviors related to HIV risk.

Data Analysis

To answer the research questions of the study, data collected from the 325 sexually active students were analyzed using the IBM® SPSS® Statistical package (version 20.0). Descriptive statistical tests were used to provide background of the study participants (N=325). Chi-square analysis was utilized to test the associations between condom use practice and risky taking behaviors which include alcohol drinking, history of drug use, drinking before sex, hookup experience, and one-night stand experience. A p-value ≤ .05 was set to determine statistical significance.

Results

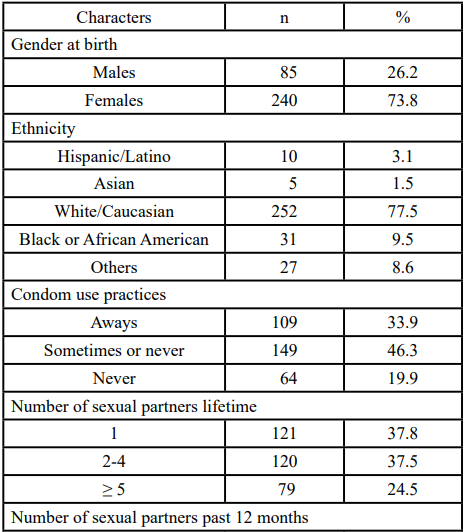

The average age of the 325 college students who had sexual experiences was 19.89 (SD = 1.57). The key social-demographic characteristics of the sexually active participants (N= 325) are presented in Table 1.

The majority of them (77.5%) self-reported their ethnicity as White /Caucasian. Among all sexually active participants (N=325), nearly a quarter of them (24.5%) reported they had at least 5 sexual partners in their lifetime. Moreover, about 30% of these sexually active participants, about 30% of them had multiple sexual partners (≥ 2 sexual partners) during the past 12 months. Only 33.9% of sexually active college students who participated in this study reported that they consistently use condoms during sexual intercourse.

Among the college students who had sexual experience (N=325) in this study, about 83.6 % of them (n=271) reported that they had drinking alcohol behavior and more then half of them (n=165) said they had alcohol drinks before sex. About6.8% of these sexually active participants (n=271) reported they had smoked cigarettes. Also, about 43.8% (n=142) of these sexually active college students in this study (N=325) reported a history of drug use.

Only five college students in this study reported that they had ever been diagnosed with any of the STIs. Most of (70.5%) the sexually active college students in this study had never been tested for HIV. Among all college students who had sexual experiences in this study (N=325), more than half (57.4%, n=138) of them had “hooking up experience” and 29.5% (n=95) had one-night stand experience.

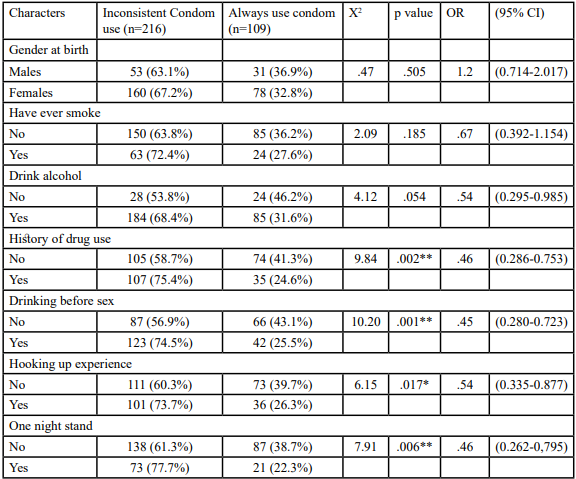

This study also revealed that condom use practice during sexual behaviors among the participants of this study was significantly associated with history of drug use (X2 = 9.84, p = .002), drinking before sex (X2 = 10.20, p = .001), hooking up experience (X2 = 6.15, p = .017), and one night stand experience (X2 = 7.91, p =. 006). Inconsistent condom use is higher among participants who had a history of using non-injection drugs, who drunk alcohol before sexual intercourse, who reported having hooking up experience, and those who had one night stand experience during sexual intercourse. The results of the Chi-square analysis summarized in the Table 2.

Discussion

Consistent with the literatures, this study found that alcohol consumption, drinking before sex, and using non-injection drugs such as marijuana and inhaled nitrite were significantly associated with higher likelihood of inconsistent condom use. In contrast to past studies that found condom use was higher in casual sex relationships than in romantic and monogamous relationships [44,11], this study discovered that college students who engaged in hookups and one-night stand experiences were less likely to use condoms consistently. However, researchers suggested considerations the influence of relationship intentions on condom use during hookups. It was suggested that college students seeking romantic connections were related to less condom use [11]. Although current or future relationship typically are not present or expected among two individuals hooking up, it is uncertain whether the college students who participated in this study were motivated to engage in hookups with the expectation of developing a romantic relationship. As hookups frequently occur in the events where alcohol or drugs are present and usually with unfamiliar partners, in unfamiliar contexts, and may be unplanned, it is not surprised that the occurrence of unprotected sex may increase with hookup behaviors.

The simultaneous effects of alcohol consumption, substance use, and hookup behaviors on condom use practices were not explored in this study. While the findings of this study indicated that drinking before sex was significantly associated with inconsistent condom use, the study did not investigate whether alcohol was consumed specifically during sexual hookup events or whether condoms were used during those encounters. Previous research showed that simultaneous use of alcohol and cannabis was significantly associated with engaging in sexual intercourse following their combined use and higher rates of unprotected sex [27]. Examining these interactions at the event level could provide deeper insights into the situational factors that drive risky sexual behaviors. Future research employing methodologies examining the simultaneous effects of alcohol consumption, substance use, and hookup behaviors on condom use practices is recommended to better capture the complexities of these associations and to inform more targeted sexual health interventions.

The findings of this study highlight important policy implications for addressing risky sexual behaviors among American college students. Given the associations between inconsistent condom use and alcohol consumption, non-injection drug use, hookups, and one-night stands, targeted interventions are essential to reduce sexual health risks and promote safer practices.

Sexual Health Education on Campuses

Colleges and universities should implement evidence-based, comprehensive sexual health education programs that emphasize the risks associated with alcohol and drug use in sexual contexts. Such programs should focus on improving condom negotiation skills, promoting consistent condom use, and addressing misconceptions about substance use and sexual decision-making [51].

It would be nice to think that students arrive on college campuses with some level of universal sexual health knowledge and risk management strategies, but in Ohio, the state in which this research was conducted, that is not possible. Ohio requires K-12 sex education that provides instruction on abstinence, prevention of venereal diseases, healthy relationships, intimate partner violence prevention, laws related to having sex with a minor, and assault prevention [52,53]. As part of the venereal disease education [52], HIV and STD instruction is provided. However, there is no requirement that the information be medically accurate, and abstinence before marriage must be emphasized [54,55]. Further, school districts can create and deliver sexual health content applicable to their local concerns, beliefs, or biases, thus creating disparities in what students across the state learn and know. Finally, the law provides parents an “opt out” option for any sexual health education.

Because of Ohio’s sexual health education laws, students arrive at college campuses with a wide variety of sexual health knowledge ranging from a medically accurate and comprehensive education from schools and parents to google searches, social media posts, and gossip sought on their own to inaccurate education provided by parents and/or educators. Discrepancies in pre-college sex education may contribute to this study's finding of inconsistent condom use. It is possible that some participants lack basic knowledge about how to use a condom or the protection it provides. This leaves colleges and universities in Ohio and 24 other states [55] in a position to both provide for students’ immediate sexual health needs and to advocate for legislative policy changes that would improve sexual health.

On Campus Changes

Campuses are ripe with opportunities to provide sexual health education to students who live on and off campus. Student health centers, typically in conjunction with the campus counseling center, frequently have educational trainings for students about substance use, violence prevention, mental health, alcohol awareness, and suicide prevention. Trainings that pair education about drinking and marijuana usage and condom usage could promote an overall harm reduction strategy for college students’ physical and sexual health. Students, specifically incoming students, often participate in a welcome week or orientation that has a host of activities and trainings for new students, and this may be one way for campuses to increased students’ sexual health education. Similarly, students living in housing participate in both mandatory dorm meetings and voluntary training activities; this may be another way to reach students and improve sexual health knowledge. Finally, some universities have a learning community for new students. While these programs can vary in the amount of academic and social/campus content provided, this may be another opportunity to get sexual health information in front of students.

Time and budgetary restrictions may be a concern for providing or increasing any sort of sexual health education. Universities with medical schools and nursing programs, as well as programs in social work, public health, health education, and gender studies may be able to tap into service-learning opportunities for students to provide sexual health training as part of a course assignment. Not only will this option optimize the time and talents of the emerging professionals, it will also allow for peer-to peer education which has been shown to be effective [56]. There are national organizations who provide free online training for those facilitating sexual health education [57]. Like students who may provide the training as part of their academic training, student groups or clubs with an interest in sexual health (e.g., Women’s Center, GLBTQ+ organizations, Panhellenic organizations with a health mission) could also help provide information to other students through trainings, health fairs, or campus events.

At a minimum, universities should have a robust website linking students to sexual health education. This could be a collaborative effort between units on campus (e.g., student health center, student support services) and linked from the home pages of multiple organization webpages (e.g. Women’s Center, Housing) to provide easy access to students seeking information. The Ohio State University [58] has a robust website that may be used as a model. Updating the information provided could also be a service-learning project for health education courses.

In addition to sexual health education, colleges should expand access to sexual health resources, including free or affordable condoms, STI/HIV testing, and contraception. Condoms and other STD barriers need to be widely available across campus. Obvious locations on campus that should make condoms available include housing, the student health center, public bathrooms, and the spaces occupied by academic programs and student organizations with a public health orientation. This study found inconsistent condom use. It is possible that a contributing factor to inconsistent usage could be assess to condoms or cost barriers. A 36 pack of condoms from Amazon can run a student upwards of $15.50, which could be a financial barrier for some. See the section on partnering with public and community health agencies to provide free condoms and other STD barriers to students for free or low cost. Additionally, establishing campus health centers as judgment-free zones for sexual health consultations can encourage students to seek care and testing. Furthermore, offering mobile health units or pop-up clinics can improve accessibility for students who may not regularly visit campus health facilities.

Policy initiatives are also important and should support campus-based alcohol and drug prevention programs to reduce substance use before or during sexual encounters. Programs should emphasize harm reduction strategies, including safer partying practices, responsible drinking campaigns, and the risks associated with combining substance use and sexual activity. Providing counseling services and confidential support for students struggling with substance abuse is also critical.

Partnerships with Community Public Health

Currently, there is no cure for HIV. However, with appropriate medical care such as antiretroviral therapy, the virus can be effectively controlled [59]. Providing education to promote sexual health and making free condoms available to students are the first steps in preventing HIV and other STDs. Several agencies provide condoms and other STD barriers for free or at low cost. For example, OHIV [60] will mail anyone over 16 free condoms every 30 days. This information could be shared with students at trainings, on the sexual health website, and at any testing day. On our campus, the volunteers of the campus food pantry committed to ordering condoms each month and donating them to the pantry to be included with the hygiene items. Planned Parenthood clinics also offer free and low-cost condoms and birth control [61]. In addition to providing condoms and birth control, Planned Parenthood [57] also has online sexual health training modules that are free to use. These modules rely on best practices in sexual health, are provided in both English and Spanish, and are in short in duration so that they are easy to incorporate into programming.

Some people may have no symptoms after being infected with HIV. The only way an individual to know whether he/she has HIV is to be tested [59]. Ultimately, students need to be tested to know their status. In this study, the majority of sexually active participants had never been tested. Education about the value of testing, as well providing easy and convenient testing, may allow students to increase their agency over their sexual health. State and county departments of public health, as well a non-profit organization may partner with university groups to bring testing to campus. This is popular programing around World AIDS Day on December 1 [62] or Sex Ed for All Month in May [63]. In addition to on campus testing, some groups may provide free at home test [64]. Publicizing this opportunity to students through flyers, social media, as part of sexual health training, and health cares expands access to private testing. Promoting and staffing testing days is also an opportunity for service learning or campus groups to patriciate [65]. Ohio does allow for prosecution of those who know their HIV status and fail to disclose it to their sexual partners [66]. Campuses would want to make sure that any agency they partner with included this information with testing notification. Collaborations between colleges and public health organizations can support large-scale awareness campaigns focused on STI/HIV prevention. These partnerships can also help develop interventions targeting high-risk groups including students with histories of substance use and STIs.

State and Federal Policies and Advocacy

Unfortunately, in Ohio, legislation to educate K-12 students about ways to promote healthy sexual behaviors has gotten more conservative in the past 5 years. Three pieces of legislation have been introduced, but not yet passed, that would have implications for sexual health education. Most notable and most restrictive, HB 616 [67] was introduced in 2022. While primarily directed at removing GLBTQ+ education in K-3 grades, this legislation would limit age-appropriate sexual health education. This compounds the lack of sex education knowledge as Ohio already under educates students; according to the Center for Disease and Control (CDC), only 11.2% of middle schools taught all 22 sexual health education topics [55,68]. Almost 40% of high schools taught all the sexual health topics. Given Ohio Republicans maintained a super majority in the 2024 elections, it is unlikely, the state will have more progressive sexual health legislation [69]. Rather, based on the passage of SB 104 [70] popularly known as the “trans bathroom bill,” sexual health legislation may become more restrictive in the coming years.

At the federal level, the Biden administration proposed a rule change that those with health insurance should be able to access free birth control, including condoms, from pharmacies and storefronts [71]. Promoting free and easy access to all forms of birth control removes barriers. Whether or not the Trump administration continues down this path is yet to be seen. However, based on the past administration [72] and current signaling [73], this rule change may not come to pass.

Further, Trump’s appointments to cabinet positions, specifically the Department of Health and Human Services and the Department of Education, may impact evidence-based dissemination of sexual health research [74]. While Trump has endorsed a proposal to “end HIV,” Republican lawmakers have not provided the CDC and other government health entities the funding to make that possible [75]. Following HIV and sexual health legislation over the next four years will be important for researchers and practitioners working in this area.

Study Limitations

Several limitations of this study must be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to infer causality between condom use practices and risky behaviors, such as alcohol consumption before sex, history of non-injection drug use, hookup experiences, and one-night stands. The findings represent associations observed at a single point in time cannot determine temporal or causal links among these variables. Second, the measures for alcohol consumption, substance use, hookup experiences, and condom use were assessed at a global level rather than an event-specific level. The situational and contextual factors associated with condom use during specific sexual encounters, such as the influence of alcohol or drug use immediately before or during sexual activity and hookup might not be captured. This lack of event-level measurements and analysis limits the ability to determine the direct influence of alcohol and substance use on condom use within specific sexual contexts. Future research using event-based designs is recommended to address these limitations and further explore the dynamic associations between these behaviors. Third, the use of a convenience sampling method may introduce selection bias, as participants who voluntarily chose to participate may differ in key characteristics from those who did not. This non-probabilistic sampling approach limits the generalizability of the findings to broader college student populations or other demographic groups. Fourth, data collection through self-administered questionnaires raises concerns about potential recall bias and social desirability bias. Participants may have underreported or exaggerated their sexual behaviors, substance use, or condom use practices, leading to inaccuracies in the data. Responses may also have been influenced by the sensitive nature of the topics, despite the anonymity provided. Future research should consider employing longitudinal designs, random sampling techniques, and mixed-method approaches to improve reliability and generalizability. Last, some psychological and social factors influencing safe sexual behaviors, such as religious beliefs, perceived social influence, autonomy, peer norms, and sexual socialization variables, were not considered in this study [76,77]. To bridge the gap between HIV knowledge and risky sexual behaviors, further research and interventions should focus on the psychological and social aspects of sexual behaviors among college students, alongside the implementation of comprehensive sexual education programs.

Future Research

Future studies should incorporate event-level data collection methods to examine the specific timing and context of alcohol and substance use in relation to sexual activities and college student’s condom use practices. Event-level analyses would allow researchers to determine whether condom use occurred at the time while alcohol and drug were used during sexual encounters or hookup behaviors and how alcohol and drug use impact condom use decisions during college students’ hookup behaviors. Moreover, gender differences may be important for future research investigating preventions of risky sexual behaviors and promoting condom use among college students. Exploring how gender influences condom use practices, alcohol and drug use before sex, and hookup culture is critical. Investigating whether gender differences moderate college student’s condom use practices during sexual hookups while alcohol and/or non-injection drug are used is suggested in future studies. Qualitative studies, such as in-depth interviews or focus groups, may also suggested for future research as they could provide richer insights into students’ perceptions of sexual risk behaviors, motivations for condom use, and attitudes toward alcohol and substance use in sexual contexts. These approaches may help uncover underlying social and psychological factors influencing decision-making. Understanding personal perceptions and motivations could help inform more effective prevention strategies.

Conclusion

This study highlights critical patterns of risky sexual behaviors among American college students. The findings indicate that students who engage in high-risk behaviors, including non-injection drug use, alcohol consumption prior to sexual encounters, and participation in hookups and one-night stands, are less likely to use condoms, putting them at higher risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and unintended pregnancies. The study also uncovered significant gaps in HIV testing, as demonstrated by the fact that the majority of sexually active students had never been tested for HIV. These findings underscore the urgent need for comprehensive sexual health education and interventions on college campuses, as well as increased collaboration between universities, public health organizations, and policymakers to promote safer sexual practices. Addressing these issues through targeted education programs, policy changes, and campus-level initiatives could help mitigate the risks and improve sexual health outcomes for college students. Policy recommendations aim to create safer campus environments, reduce health disparities, and promote responsible decision-making among college students. Comprehensive and multi-level approaches are essential to reduce the adverse outcomes associated with risky sexual behaviors.

Acknowledgments:

This research was partially supported by an award from the Sigma Theta Tau International Honor Society of Nursing (STTI) Small Grants. The researchers sincerely thank all faculty who grants permissions allowing access to their students for data collection and all students who participated in this study.

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

CDC. (November, 2024a). Fast facts: HIV in the US by age. Retrieved December 28, 2024 from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/ data-research/facts-stats/age.htmlView

National Center for Education Statistics. (2023). Characteristics of Postsecondary Students. Condition of Education. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. Retrieved [date], from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/ indicator/csb.View

SAMHSA. (2016). A day in the life of college students aged 18 to 22: substance use facts. Retrieved on December 29th, 2024 at https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/report_2361/ ShortReport-2361.html View

Brown, J. L., Gause, N. K., & Northern, N. (2016). The association between alcohol and sexual risk behaviors among college students: A Review. Current Addiction Reports, 3(4), 349–355.View

Romm, K. F., Metzger, A., Gentzler, A. L., & Turiano, N. A. (2022). Transitions in risk-behavior profiles among first-year college students. Journal of American College Health, 70(7), 2210–2219.View

CDC (September, 2024b). How HIV Spread. Retrieve from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/causes/index.html View

CDC. (2024c). HIV Risk Behaviors. Retrieved from https:// www.cdc.gov/youth-behavior/risk-behaviors/sexual-risk-behaviors.html View

American College Health Association (2019). American college health association-national college health assessment ii: undergraduate student executive summary spring 2019. Silver Spring, MD: American College Health Association. View

Garcia, J. R., Reiber, C., Massey, S. G., & Merriwether, A. M. (2012). Sexual hookup culture: A review. Review of General Psychology, 16(2), 161–176. View

Garcia, T. A., Litt, D. M., Davis, K. C., Norris, J., Kaysen, D., & Lewis, M. A. (2019). Growing up, hooking up, and drinking: A review of uncommitted sexual behavior and its association with alcohol use and related consequences among adolescents and young adults in the United States. Frontiers in psychology, 10, 1872.View

Hall, W. J., Erausquin, J. T., Nichols, T. R., Tanner, A. E., & Brown-Jeffy, S. (2019). Relationship intentions, race, and gender: student differences in condom use during hookups involving vaginal sex. Journal of American College Health, 67(8), 733–742.View

Hollis, B., Sheehan, B. E., Kelley, M. L., & Stevens, L. (2022). Hookups among U.S. college students: Examining the association between hookup motives and personal affect. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51(3), 1793–1798. View

Pham, J. M. (2017). Beyond hookup culture: Current trends in the study of college student sex and where to next. Sociology Compass, 11(8), n/a-N.PAG. View

Thomson, L., Zeigler, S., Kolak, A. M., & Epstein, D. (2015). Sexual hookups and alcohol consumption among African American and Caucasian college students: A Pilot Study. The Journal of psychology, 149(6), 582–600. View

Claxton, S. E., DeLuca, H. K., & van Dulmen, M. H. (2015). The association between alcohol use and engagement in casual sexual relationships and experiences: a meta-analytic review of non-experimental studies. Archives of sexual behavior, 44(4), 837–856. View

Tucker, J. S., Shih, R. A., Pedersen, E. R., Seelam, R., & D'Amico, E. J. (2019). Associations of alcohol and marijuana use with condom use among young adults: The moderating role of partner type. Journal of Sex Research, 56(8), 957–964. View

LaBrie, J. W., Hummer, J. F., Ghaidarov, T. M., Lac, A., & Kenney, S. R. (2014). Hooking up in the college context: the event-level effects of alcohol use and partner familiarity on hookup behaviors and contentment. Journal of sex Research, 51(1), 62–73. View

Patrick, M. E., & Maggs, J. L. (2009). Does drinking lead to sex? Daily alcohol–sex behaviors and expectancies among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 23(3), 472-481.View

Thorpe, S., Tanner, A. E., Kugler, K. C., Chambers, B. D., Ma, A., Hall, W. J., Ware, S., Milroy, J. J., & Wyrick, D. L. (2021). First-year college students’ alcohol and hookup behaviours: Sexual scripting and implications for sexual health promotion. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 23(1), 68-84. View

Owen, J. J., Rhoades, G. K., Stanley, S. M. & Fincham, F. D., (2010). “Hooking Up” among college students: Demographic and psychosocial correlates. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39, 653-663.View

Lu, H. Y., Ma, L. C., Lee, T. S., Hou, H. Y., & Liao, H. Y. (2014). The link of sexual sensation seeking to acceptance of cybersex, multiple sexual partners, and one-night stands among Taiwanese college students. The Journal of Nursing Research, 22(3), 208- 215. View

American College Health Association. (2022). American college health association—national college health assessment III: Undergraduate student reference group executive summary spring 2022. American College Health Association. View

Arria, A. M., Caldeira, K. M., Allen, H. K., Bugbee, B. A., Vincent, K. B., & O'Grady, K. E. (2017). Prevalence and incidence of drug use among college students: an 8-year longitudinal analysis. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 43(6), 711–718. View

Kivlichan, A. E., Lowe, D. J. E., & George, T. P. (2022). Substance misuse in college students. Psychiatric Times, 39(5), 19–21. View

Hai, A. H., Carey, K. B., Vaughn, M. G., Lee, C. S., Franklin, C., & Salas-Wright, C. P. (2022). Simultaneous alcohol and marijuana use among college students in the United States, 2006-2019. Addictive behaviors reports, 16, 100452.

Skidmore, C. R., Kaufman, E. A., & Crowell, S. E. (2016). Substance use among college students. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 25(4), 735–753. View

Kolp, H., Horvath, S., Munoz, E., Metrik, J., & Shorey, R. C. (2024). Simultaneous alcohol and cannabis use and high-risk sexual behaviors. Cannabis (Albuquerque, N.M.), 7(2), 1–10. View

Schulenberg, J. E., Johnston, L. D., O’Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G. Patrick, M. E. (2019). Monitoring the future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2019: Volume II, college students and adults ages 19-60. View

Robbins, T., Wejnert, C., Balaji, A. B., Hoots, B., Paz-Bailey, G., Bradley, H., & NHBS-YMSM Study Group (2020). Binge drinking, non-injection drug use, and sexual risk behaviors among adolescent sexual minority males, 3 US Cities, 2015. Journal of Urban Health, 97(5), 739–748. View

Berry, M. S., & Johnson, M. W. (2018). Does being drunk or high cause HIV sexual risk behavior? A systematic review of drug administration studies. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 164, 125-138. View

Chen, S., Yang, P., Chen, T. et al. (2020). Risky decision-making in individuals with substance use disorder: A meta-analysis and meta-regression review. Psychopharmacology 237, 1893–1908. View

Cho, H-S, & Yang, Y. (2023). Relationship between alcohol consumption and risky sexual behaviors among adolescents and young adults: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Public Health, 68. View

Scott-Sheldon, L. A., Carey, K. B., Cunningham, K., Johnson, B. T., Carey, M. P., & MASH Research Team (2016). Alcohol use predicts sexual decision-making: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the experimental literature. AIDS and behavior, 20 Suppl 1(0 1), S19–S39.View

Welsh, J. W., Shentu, Y., & Sarvey, D. B. (2019). Substance use among college students. Focus, 17(2), 117–127. View

Liu, Y. & Vermund, S.H. (2017). Non-injecting Drug Users, Epidemiology of HIV/AIDS. In: Hope, T., Richman, D., Stevenson, M. (eds) Encyclopedia of AIDS. Springer, New York, NY. View

Brown, J. L., & Vanable, P. A. (2007). Alcohol use, partner type, and risky sexual behavior among college students: Findings from an event-level study. Addictive Behaviors, 32(12), 2940– 2952. View

Walsh, J. L., Fielder, R. L., Carey, K. B., & Carey, M. P. (2014). Do alcohol and marijuana use decrease the probability of condom use for college women? Journal of Sex Research, 51(2), 145–158. View

SAMHSA (2019). Center for Behavioral Statistics and Quality: National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Table 6.23B—Alcohol Use Disorder in Past Year among Persons Aged 18 to 22, by College Enrollment Status and Demographic Characteristics: Percentages, 2018 and 2019. Accessed December 25, 2024 from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/ default/files/reports/rpt29394/NSDUHDetailedTabs2019/ NSDUHDetTabsSect6pe2019.htm#tab6-23b. View

Chandler, L., Abdujawad, A. W., Mitra, S., & McEligot, A. J. (2021). Marijuana use and high-risk health behaviors among diverse college students post- legalization of recreational marijuana use. Public health in practice (Oxford, England), 2, 100195. View

Schumacher, A., Marzell, M., Toepp, A. J., & Schweizer, M. L. (2018). Association between marijuana use and condom use: A meta-analysis of between-subject event-based studies. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 79(3), 361–369. View

WHO. (2024). Condom. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/ news-room/fact-sheets/detail/condoms View

Stover, J., & Teng, Y. (2022). The impact of condom use on the HIV epidemic. Gates open research, 5, 91. View

Fehr, S.K., Vidourek, R.A. & King, K.A. (2015). Intra- and Inter-personal barriers to condom use among college students: A review of the literature. Sexuality & Culture 19, 103–121 (2015). View

Godinho, C.A., Pereira, C.R., Pegado, A., Luz, R., Alvarez, M-J. (2024). Condom use across casual and committed relationships: The role of relationship characteristics. PLoS ONE 19(7): e0304952. View

Macaluso, M, Demand, M. J., Artz, L. M., & Hook, E. W. III. (2000). Partner type and condom use. AIDS, 14(5), 537-546. View

Kanekar, A., & Sharma, M. (2009). Factors affecting condom usage among college students in South Central Kentucky. International Quarterly of Community Health Education, 28(4), 337-349.View

Menon, J. A., Mwaba, S. O. C., Thankian, L., & Lwatula, C. (2016). Risky sexual behaviour among university students. International STD Research & Reviews, 4(1), 1-7. View

Elshiekh, H. F., Hoving, C., & de Vries, H. (2020). Exploring determinants of condom use among university students in Sudan. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(4), 1379-1391. View

McCarthy, D., Felix, R. T., & Crowley, T. (2024). Personal factors influencing female students’ condom use at a higher education institution. African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine, 16(1). View

Lee, J. (2022). Factors affecting condom-use behaviors among female emerging adults in South Korea. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 15, 1771-1781. View

Whiting, W., Pharr, J. R., Buttner, M. P., & Lough, N. L. (2019). Behavioral interventions to increase condom use among college students in the United States: A systematic review. Health Education & Behavior, 46(5), 877–888. View

Ohio Laws and Administrative Rules (2024a). Instruction in venereal disease education emphasizing of abstinence, Section 3313.6011.

Ohio Laws and Administrative Rules (2024b). Unlawful sexual conduct with a minor.

Sex Ed Collaborative (n.d.). Ohio – state sex education policies and requirements at a glance. View

SIECUS (2023). Ohio state of sex ed. View

Ogul, Z., & Sahin, N. H. (2024). The effect of an educational peer-based intervention program on sexual and reproductive health behavior. Journal of Adolescence, 96(7), 1642–1654. View

Planned Parenthood (2024a). Sex ed to-go for teachers. View

Ohio State University (2024). Sexual health. View

CDC. (2024d). HIV. Retrieve from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/ View

OHIV (2024). Free condoms. View

Planned Parenthood (2024b). How do I get condoms? View

CDC. (2024e). HIV awareness days. View

Healthy Teen Network (2024). Save the date! May is sex ed for all month. View

Ohio Department of Health (n.d.). HIV prevention. https://odh. ohio.gov/know-our-programs/hiv-prevention

Blankenship, B. (2021, September 10). WSU group holds HIV testing and promotes sexual health. The Guardian. View

Schnick, K., & Dissell, R. (2024). How Ohio laws criminalize HIV. The Marshall Project. View

HR 616, 136th General Assembly. (2022).

CDC. (2022). School Health Profiles. View

Trau. M. (2024, November 6). How the 2024 election impacts balance of power in Ohio statehouse. Ohio Capitol Journal. View

Henry, M. (2024, November 27). Ohio Gov. Mike Dewine signs transgender bathroom bill into law. Ohio Capitol Journal. View

Seitz, A. (2024, October 21). White House says health insurance needs to fully cover condoms, other over-the-counter birth control. AP News. View

Planned Parenthood (2018, April 20). Trump—Pence administration seeks to radically remake the teen pregnancy prevention program to now push abstinence only. View

Bernstein, A., Fredric-Karnik, A., & Damavandi, S. (2024). 10 reasons a second Trump presidency will decimate sexual and reproductive health. Guttmacher Institute. View

Lovelack, B., Burns, D. & Srricker, L. (2024, November 2024). Trump picks RFK Jr., anti-vaccine activist, for health and human services secretary. NBC. View

Miller, A. & Whitehead, S. (2023, August 31). Trump launched an ambitious effort to end HIV. House Republicans want to defund it. NPR. View

Kanekar, A., & Sharma, M. (2010). Determinants of safer sex behaviors among college students. Acta Didactica Napocensia, 3(1), 27-38. View

Walcott, C. M., Chenneville, T., & Tarquini, S. (2011). Relationship between recall of sex education and college students’ sexual attitudes and behavior. Psychology in the Schools, 48(8), 828-842. View