Journal of Social Work and Welfare Policy Volume 3 (2025), Article ID: JSWWP-138

https://doi.org/10.33790/jswwp1100138Research Article

Exploring Community Gardens and Race in The Deep South

Jennifer F. Jettner, PhD, MSW

Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology, Anthropology and Social Work, Auburn University, 7064 Haley Center, Auburn, Alabama 36849, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Jennifer F. Jettner, PhD, MSW, Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology, Anthropology and Social Work, Auburn University, 7064 Haley Center, Auburn, Alabama 36849, United States.

Received date: 24th September, 2024

Accepted date: 17th March, 2025

Published date: 21st March, 2025

Citation: Jettner, J. F., (2025). Exploring Community Gardens and Race in The Deep South. J Soci Work Welf Policy, 3(1): 138.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Community gardens are promising interventions to address a host of issues; however, little is known about those in the Deep South. Given the history of slavery and racial divides in the South, it is important to understand how race, white privilege, and historical trauma might impact the success of these interventions. Using racial capitalism and black geographies as a the theoretical framework, the purpose of this qualitative study was to explore community gardens in Alabama, US. Ten garden leaders were interviewed representing nine community gardens that were a mix of urban and rural. Interviews were transcribed and analyzed for themes. Main findings were health-focused efforts were white-led while justice-focused efforts were BIPOC-led. Still, all community gardens had difficulty engaging a racially diverse community garden reflective of the neighborhood. Importing racial diversity rather than celebrating BIPOC leadership and knowledge appeared to be the main impediment for white-led efforts. BIPOC-led efforts had differing interpretations of the impact of historical trauma which may be related to a “rural imaginary”. All struggled to engage youth and feared losing food and growing knowledge generationally. Implications for practice, policy, and research are discussed.

Keywords: Sustainable Agriculture, Diversity, Race and Racism, Black Geographies, Racial Capitalism, Historical Trauma

Introduction

Community gardens are ideal and idealized interventions. They are ideal because research has found that community gardens can increase food access, promote mental health and community cohesion [1,2], reduce crime and blight [3], and mitigate the effects of climate [4]. They are idealized because they have captured the interest of a wide range of groups. Community gardens are not only initiated by concerned citizens (e.g., grassroot efforts) but increasingly by nonprofits and local municipalities and receive support from national foundations and federal funding [5]. Furthermore, community gardens are now a global phenomenon, particularly as important components of a sustainable food system [6]. One could argue that community gardens have entered a new age, given the current global crises of climate change, income inequality, and the seeming inability of government to provide solutions due to highly divisive politics.

Defining Community Gardens

Community gardens are broadly defined as places where a group of people garden that are in some way “public in terms of ownership, access, and degree of democratic control” [7]. This definition can encompass a wide array of community gardens. Often, they are in neighborhoods typically initiated by a core group of citizens using vacant or dilapidated lots. They can have individual plots that individuals rent or be communal gardens where people garden collectively. However, given catholic interests, some are part of nonprofit initiatives who wish to address food insecurity in low-income neighborhoods [8,9].

Social Work: Disentangling Critiques & Contradictions

Community gardens have also been critiqued for perpetuating neoliberalism, white privilege, and gentrification while also lauded as transformative spaces to develop a community care ethic based on a moral economy [10,11]. Roman-Alcala [12] has commented on the “unbearable whiteness” in these efforts and McClintock [13] has even argued that “who” initiates these efforts will likely determine the social justice impact they might have. Community gardens have also been deemed as examples of environmental social work [14]. However, social work must have a greater and more nuanced understanding of how white privilege operates within community gardens and other alternative food initiatives to promote social, economic, and environmental justice.

Literature Review

Racial Capitalism & Black Geographies

Critical research has used racial capitalism and black geographies as part of its theoretical framework, generating insights about the contradictory nature and processes of race and privilege within community gardens and other alternative community food projects. Racial capitalism helps focus attention on the unequal development of space and place in which racially marginalized people are commodified, made “place-less”, and relegated to the “worst” places. Given this long history, White epistemologies regarding nature and land have developed differently from BIPOC folk. Black geography de-centers the white actor and examines black survival and liberatory practices within racial capitalism. This section will first discuss racial capitalism and black geographies, and then situate this framework and empirical evidence within the context of community gardens (and other community food projects) to discuss what is known about how white privilege operates, the challenges of black liberation given a capitalist market and historical trauma, and finally, what might white allyship look like in this context?

Racial Capitalism

Racial capitalism refers to “the idea that capitalist accumulation requires human difference and, in the process of exploiting it, reifies socio-spatial differentiation” [13]. There are several points to clarify here. First, race and class are not viewed as static concepts [15]. Instead, racism and capitalism are viewed as ideological processes that work in concert that have material and cultural consequences. Racial capitalism has produced, and still produces, a global capitalist system in which Black, Brown, and Indigenous people have experienced dispossession, erasure, and outright genocide. London and colleagues (2021) argue that “racial capitalism understands that capitalism is racial, was never not racial; and that racism enabled capitalism’s rise to dominance in Europe via a globalized system of chattel slavery and settler colonialism” (p. 206).

The other point to clarify is exploiting and reifying socio-spatial differentiation. Racial capitalism is a social system in which people are deemed inferior based on skin color to justify the exploitation of their land and/or labor. It is also a physical system in which places are coded as “good” and others as “bad”. In other words, racism is literally built into the physical environment. On a global scale, the world is divided into so-called First World and Third World nations, remnants of imperial colonialism. In the US, racist policies have relegated a host of racialized subjects into impoverished places. This history is so vast that it is difficult to summarize. Please see Lipsitz’s [16] Possessive Investment in Whiteness for a comprehensive account. Still, briefly discussing Black History in the US is necessary to illustrate this point and provide historical context.

We begin with the Trans-Atlantic slave trade and chattel slavery, which occurred throughout the colonies, but by the time of the Civil War, chattel slavery was practiced mainly in the rural Deep South. Despite the abolishment of slavery, Black people endured the Black Codes, which criminalized black life providing cheap labor through the convict leasing system, and legalized racial apartheid during Jim Crow [17]. Reduced to sharecropping or domestic servitude in the rural South, approximately six million Black people left for opportunity in urban cities up North, the Midwest, and the West during the Great Migration which occurred after WWI [18]. Racism, however, existed everywhere in the US, not just in the rural South. Black people (as well as other BIPOC folk) faced discrimination in employment and housing (e.g., racial covenants, redlining) which in effect, warehoused Black people in specific neighborhoods with tenement housing stock, already dilapidated from previous Irish and Italian immigrants, former racialized subjects [13]. White flight to suburbia and subsequent disinvestment in urban housing created inner-city neighborhoods, often code for black and brown urban poverty, that lacked access to decent employment, housing, schools, and other basic amenities [18].

We can still see the impact of this historical, structural, and state-sanctioned violence to this day, differentiating urban and rural poverty – socially and spatially. Rural poverty is greatly concentrated in the deep South, disproportionately impacting black communities who also face greater environmental racism that negatively impact human health [19], and even lack basic amenities such as sanitation systems [20]. In terms of urban poverty, one can easily overlay historic redlining maps of cities with urban food deserts today to see how redlined areas then, are the food deserts of today. Food deserts are not ahistorical but symptomatic of historic and racialized disinvestment.

Black Geographies

Rooted in critical race theory, black geography is concerned with the production of “race and racism via the production of space” [15]. Scholars have used black geography to examine the Black diaspora, carceral geographies, as well as racial capitalism [15]. However, black geography does not simply seek to understand the processes of racial oppression vis a vis the uneven development of space (e.g., land) that displace, erase and marginalize black bodies and black places. Critically, black geography also seeks to de-center the white actor and instead highlight black agency in everyday placemaking, survival strategies, political acts, and liberatory practices [15,21]; plantation futures and black agrarianism are exemplars of this type of scholarship [15].

Plantation futures situates black agrarianism within a framework that juxtaposes the slave plot with the plantation [15,21,22]. Slave plots are evidence of plantation survival strategies, black autonomy and agency, and provide hope for black liberation while living within an oppressive regime. Thus, what can we learn from this history that provides strategies and possibilities for today – that is, “make a way out of no way” [22]? Enslaved women were particularly valuable for their agricultural knowledge; they were the ones who cooked and fed during the Middle passage, they were the ones who knew how to grow rice, they were the ones who primarily cultivated slave plots and fed their community, and they were the ones with the medicinal knowledge who grew herbs to care for the sick among black and white folk [22]. As Malik Yakini states, a black urban farmer and activist, Black people were enslaved because they were the best farmers in the world [23]. Perhaps Yakini’s statement is hyperbole. The point of this scholarship, however, is to reclaim black agricultural knowledge as a source a pride and that black lives had value – so valuable, they had to be dehumanized to be commodified. Given that black lives currently tend to be treated as disposable, this statement of pride and having value can be powerful indeed.

Land, food, and farming have long been a part of black liberation theory and movements. During the Civil Rights era, the Black Panthers provided free breakfast to children [24] as a community-led survival strategy, which Ramirez [21] argues is reminiscent of plantation survival strategies, and political activity that arguably led to the federal government providing free and reduced school meals to poor children decades later. Several Black-led farming movements occurred during this time, where growing food was a way to produce community “self” sufficiency, Black autonomy, and economic wealth [21,22,24]. There are several historical examples of these farms, such as those developed by the Nation of Islam [25]; however, McCutcheon’s [22] fine-grained analysis of Fannie Lou Hamer’s Freedom Farms in rural Mississippi is especially germane to this discussion.

Fannie Lou Hamer was a Civil Rights activist largely known for her work on voting rights; however, she developed the Freedom Farms Cooperative in 1969, the purpose of which was to provide freedom from hunger, poverty, and inadequate housing for the black community [22]. This coop provided land to black families to grow their own food and cash crops, land for housing and helped families apply for FHA loans, financial assistance to students and local school systems, and start-up loans for black businesses. Land ownership, specifically collective land ownership, was crucial for black liberation. According to Hamer, community ownership enabled “group development of economic enterprises” that benefited the entire community whereas individual ownership facilitated “monopolies that monopolise the resources of a community” [22]. Members were not required to pay into the coop, since Hamer knew that those most in need likely wouldn’t have the funds. While the Freedom Farms made use of federal grants, Hamer did not want to rely on federal funding suspicious of how long they would be available or even if they would receive this assistance. Hamer relied mostly on donations and income generated from her speaking engagements in the hope that in time, Freedom Farms would be self-sufficient. Sadly, McCutcheon [22] observes that perhaps so much emphasis was placed on the Freedom aspect and not enough on the Farming aspect that Hamer’s “social justice work was effectively crippled by the demands of agribusiness” (p. 219). In short, it was difficult to make Freedom Farms profitable enough to sustain the black community given the need for large capital investments, a reliance on an under-resourced community, and the vagaries of federal assistance.

Application to Current Alternative Food & Farming Context

Based on their in-depth qualitative analysis of urban agriculture than spanned several years in Sacramento, CA, London and colleagues (2021) develop a useful framework – market-rooted, health-rooted, and justice-rooted – to organize their results around race and privilege. Notably, questions around race and privilege were not part of their original research agenda; however, this topic was so prevalent that they turned to racial capitalism and black geographies as their theoretical framework to make sense of their findings. These “taproots” represent the primary orientation or purpose of these alternative community food projects; however, these “roots” can be entangled in practice. Thus, this next section uses their framework as an organizing tool for current empirical literature but highlights different forms of white privilege and approaches to entrepreneurship within each to help disentangle these “roots”.

Market-Rooted: Farming Pioneers in the New Food & Farming Frontier

Market – rooted projects focus on using the power of capital to develop local and regional food systems that are organic, sustainable, and commercially successful [26]. There is little to no engagement with multiple social justice issues that span the production to consumption continuum within conventional agriculture. Due to a naïve sense of colorblindness, there is no awareness or critical analysis that questions the causes of food insecurity, the environmental harms (e.g., pesticides) that farmworkers often face, and it is universally assumed that this new alternative food system will be equally beneficial to all.

Because the focus is on being green and profitable, these projects tend to grow high-value products (e.g., niche specialty crops) sold at boutique restaurants, usually at exorbitant prices. Further, these projects often use growing methods that require high capital investments (e.g., automation) in the short-term but reduce labor costs in the long-term. As such, these projects do not produce affordable food or living wage employment. Instead, they “adopt a neo-liberal stance” [26] that encourages entrepreneurship and self-reliance; and, as far as politics goes, the focus is on consumer politics via “vote with your fork” [27] where it is on the individual to “pay the true cost of food” [28]. Pudup [29] has observed that even community gardens – which may not be profit-focused – can produce “neoliberal subjectivities” where individuals govern themselves by taking responsibility for growing their own food, and often, these “community” gardens can simply be places where individuals garden in the same place – there is no sense of community or connecting their activity for social change. In short, these market-rooted projects end up producing a two-tiered food system – one for the wealthy and one for the poor [30].

Much of the critique around white privilege has focused on this new alternative food system that predominantly serves an affluent white class by a relatively affluent white class – those who tend to be environmentally conscious, educated, white, and young [31]. Alkon and McCullen [28] found in their study of farmers’ markets and community-supported agriculture (CSA) that the main reason white participants gave for the lack of racial diversity was that racial minorities either did not care about environmental issues or needed to learn how to budget so they too could pay the “true cost of food”. Even though black and brown folk historically and currently (e.g., migrant farmworkers) have more than paid the “true cost of food” [32]. Recent scholarship has focused on the “unbearable whiteness” within urban farms and community gardens finding that white-led organizations tend to have more resources, such as grants and donors [33-35] white urban farmers have easier access to capital, such as loans [18], and that affluent white community gardeners simply have more time [34].

This strain of white privilege, characterized by naïve colorblindness and universalistic assumptions, also reinforces a “white imaginary” [26] alternatively described as a “white imagination of the farm” [21] or a “white pioneer imaginary” that envisions the “wild frontier as empty” (ignoring Indigenous peoples), can perpetuate a bootstrap mentality and create new forms of dispossession [13]. Echoing the past, these white pioneers view themselves as modern homesteaders successfully converting dilapidated vacant lots – the new food and farming frontier – into its highest use value. As for perpetuating a bootstrap mentality – if I can do it, anyone can – while ignoring systematic advantages due to white privilege, the ease in which capital can be accessed is shocking. For example, Riordan and Rangarajan [18] share how a white family who had just moved to a predominantly Black urban neighborhood were able to obtain 25 vacant lots to homestead for only a few dollars. McClintock (2018) describes this process as a “settler-colonial” logic that creates a new form of dispossession, because community gardens and urban farms in low-income neighborhoods are associated with gentrification [36] that push black and brown residents from their homes.

According to Ramirez [21], this “white imaginary of the farm” also erases BIPOC presence in food, farming, and even nature in the past and the present. Indeed, a Latino participant expressed puzzlement over the “historical amnesia” demonstrated by the white led alternative food movement in California who valorize eating locally and growing one’s own food as if it were something new – even though multiple racial minorities (e.g., Asians, Latinos, etc.) have been key contributors to California’s well-known agricultural system. In short, why are they not seen? Further, when they are seen, they are viewed as intruders. Several studies have documented the dangers of “gardening while black” referring to instances when black gardeners were arrested or stopped by the police when entering their community garden [18,26]. This “white imaginary of the farm” is a romanticized version of a “white farm” that also erases and excludes racial minorities from the environment or “nature”. “BIPOC folk do not care about the environment” is an oft cited rationale for the lack of racial diversity across many environmentally conscious projects (e.g., farmers’ markets), venues (wilderness parks), and advocacy groups [37]. Critically questioning this stereotype is the basis for the Environmental Justice movement, in which scholars highlight that BIPOC folk do care about environmental issues, may relate to nature differently due to historical trauma, and often interpret “nature” as where we “live, work, and play” – not as an “empty wilderness out there” that white environmentalism seeks to protect [38].

Health-Rooted: Missionaries in the New Food & Farming Frontier

Health-rooted projects share the overarching goal in creating a local and regional food system using organic and sustainable means; however, the focus is mainly on addressing public health concerns, by reconnecting people to “real” food via community gardens, gardening and healthy eating education, and changing public policy [26]. There is greater awareness that racial minorities are disproportionately impacted by food insecurity and live in food deserts (areas without easy access to major grocery stores) that contribute to racialized health disparities (e.g., obesity, diabetes, etc.). Nevertheless, proponents often lack a structural analysis of racism and instead focus on increasing access [24,26], often described as a “missionary zeal” to “bring good food to others” [32].

This missionary zeal is another form of white privilege, also characterized by colorblindness and universal assumptions; however, universalistic tendencies are moralistic and eating healthy food is framed as a personal choice once the problem of access is “solved” [21,24,32]. In short, “white” food is the “right” food. Activists in this vein have been particularly successful and creative in increasing access for low-income groups: SNAP benefits are now widely accepted at farmers markets, fresh produce is sold in convenience stores, and/or farmers’ stands operate in food deserts. However, white-led organizations often initiate community gardens in low income neighborhoods with little to no consultation with residents and unfamiliar food is grown, such as arugula vs collards [39], largely due to pervasive stereotypes that BIPOC folk do not have “healthy” food [40]. Furthermore, when the lack of racial diversity is noted, the problem is one of education (e.g., “if only they knew”) rather than structural constraints that comes with living in poverty (e.g., lack of time or kitchen appliances), or even the stigma that surrounds charity. As Guthman [32] notes, one woman simply wanted to shop at a “regular” grocery story like everyone else.

Not only is “white” food the “right” or moral choice, so too is “white” knowledge or formal knowledge the correct knowledge [18,21,24]. Multiple studies have documented how BIPOC folk are excluded from leadership and employment in white-led nonprofits due to lacking a university degree, relevant experience (often obtained via unpaid internships), or low entry-level salaries [18]. For example, Bradley and Herrera [24] describe a white manager of a large community garden in a predominantly Black and Brown community in California. This garden manager was “pleasant” and had completed his apprenticeship at a university specializing in alternative sustainable agriculture. Notably, “he talked about the Latino gardeners growing plants he did not recognize, that they then sold in street markets about which, he said, he knew nothing” (p. 98). And yet, he was in a position of leadership – which begs the question of whose knowledge is valued?

This form of white privilege, secure in its “knowledge” to be in a position of authority to “bring good food to others” can lead to erroneous assumptions even when trying to collaborate across race and class. Leaders in predominantly white-led organizations have expressed frustrations in collaborating across race, citing “cultural” differences rather than understanding structural barriers to “meeting deadlines” when relying on little to no resources such as volunteers [21]. More often, the desire for inclusion is defined solely as the participation of those they wish to serve. Some naively assume that they simply need to find the “right” messaging or outreach strategies [21] instead of decision-making power or ownership of the means of production. Consequently, many are bewildered by the lack of participation of racial minorities. They do not “see” how they create spaces encoded as “white”, described as white viscosity, meaning these places are often more comfortable for a white middle class to traverse, such as high-end tasting dinners as a fundraiser [21,26]. They do not “see” how their top-down approach can be viewed as “invading” or “colonizing” black and brown neighborhoods, often leading to well-founded fears of gentrification among residents [13]. Indeed, they do not “see” how their missionary zeal can also lead to dispossession paved on the road of good intentions.

Justice-Rooted: Liberation in the New Food & Farming Frontier

Justice-rooted projects also share the overarching goal in creating a local and regional food system using organic and sustainable means; however, strategies are grounded in a historical analysis of racial capitalism that explains present oppressive conditions for black and brown bodies. Often led by BIPOC folk, food and farming are viewed as means of liberation for empowerment and community transformation. To that end, these efforts combine the entrepreneurial and educational aspects from the previous “rooted” projects, but also includes a focus on ownership, leadership, and decision-making power. Further, these spaces are venues to “excavate historical traumas” while de-centering the “white actor” to demonstrate that BIPOC folk have been and still are integral to feeding the nation because of their knowledge and skills [21,26,41].

The goal of community transformation is interesting because empowering the “self” and the “community” are intertwined [41], which can be seen in how entrepreneurial and educational efforts are combined to build wealth and independence communally. For example, several Black-led community gardens have used Ubuntu, an African collectivist philosophy that emphasizes our “shared humanity, generosity, and common effort” as their framework to guide their activities [26]. These community gardens or urban farms grow food and value-added products (e.g., medicinal herbs, etc.), provide education and training, focus on youth development, and host social events. All of which are geared towards feeding the community, building a sense of community, and creating opportunities for employment and micro-businesses that can provide a viable path out of poverty for youth and adults [23,26]. Indeed, in one case, a Black community gardener highlighted how their communal plot was evidence of their rejection of individualism [41], as opposed to the individual plots one can rent typically found in community gardens.

There are historical reasons that the “self” and the “community” are interconnected. In a case study of Black community gardeners in public housing in DC, Reese [41] found that examinations of the “self in self-reliance almost always reflect(ed) an interest and commitment to community” (p. 412). Leaders were not necessarily rejecting individualism or even capitalism. Some simply began to grow for themselves but also become invested in the community because they too knew the struggle [26]. Hence, aspirations for community transformation as well as food justice – the right to food that is culturally appropriate, sustainable, and humanly produced – and food sovereignty – having control over one’s food system – are tied to the idea of human rights and the desire for self-determination [26,18]. When one has been historically dehumanized and denied freedom, to claim food as a human right is to claim to be human. To claim sovereignty and self-determination is to claim agency and freedom. Albeit, justice, sovereignty, and even self-determination can be viewed as academic or activist terms. The black gardeners in Reese’s [41] case study used “self-reliance” and “community reliance” to highlight their desire for black agency, as well as not relying on white charity, which is very reminiscent of Hamer’s Freedom Farm [22].

Nevertheless, these efforts can also struggle with engaging BIPOC folk due to historical trauma. In her case study of a black-led community garden in Seattle, Ramirez [21] found that even when leaders were members of the community themselves, gardening was perceived to be demeaning, especially among black adolescents [21]. Engaging black teens typically was short term and they had to be paid; although younger children were more easily engaged [21]. These black leaders worried over youth developing a “collective memory” based on horror stories shared by previous generations but they themselves have no direct connection to growing – “instead of blaming the system…they blame the land” [21]. In a study of community gardens in Virginia, Black leaders stated that connecting community gardening to slavery was “stinking thinking” and that there was “no short cut” to this issue, they simply needed to “talk about it” [10]. In these cases, “excavating historical trauma” needs to discuss how the “plot” was a plantation survival strategy that has been connected to black liberation efforts (e.g., Black Panthers, Hamer’s Freedom Farms, etc.). Relatedly, another case study of black community gardeners in DC found that older residents noted that they used to have gardens everywhere and wondered why they were gone [41]. Without this historical knowledge which engenders a sense a pride, one can lose the agricultural knowledge, and in effect, become dependent on a conventional food system that is killing them. This is why representation matters [13,18,21,26].

There are challenges, however, with integrating entrepreneurship to build wealth and economic independence. Studies have found that these efforts can also be “pushed towards” focusing on growing high-end, value-added products (e.g., herbs, medicinal tinctures, etc.) or niche crops to sell to restaurants and other boutique clientele [18]. This push towards a higher end market is necessary for these efforts to subsidize their own efforts as well as create meaningful microbusinesses opportunities. And yet, in doing so, these efforts end up producing food that is not affordable for a low-income community thus, reducing or minimizing the impact on food access, nutrition, and health. Indeed, as Riordan and Rangarajan [18] aptly state, their “success ends up being rooted in the privilege that food justice activists seek to dismantle” (p. 532). In many ways, this challenge mirrors the same challenges that Hamer faced in her Freedom Farm. The question remains, how to be “anti-capitalist” in a capitalist system?

Solidarity in the New Food & Farming Frontier: Possibilities & Pitfalls

To summarize, market-rooted efforts emphasize entrepreneurship and profit. White privilege in this context looks like the “white pioneer” bravely farming in the new, typically urban, frontier to create a local and regional sustainable food system. White privilege enables these “pioneers” to more easily access capital and other resources, making financial success more likely. However, unawareness of their privilege enables a bootstrap mentality, ignores BIPOC presence in agriculture, and when social justice is thought of at all, it is narrowed to environmental protection of the Earth while disregarding, farmworkers, food insecurity, and potential displacement through gentrification. Health-rooted efforts emphasize food access and education to improve health. White privilege in this context looks like a “missionary zeal” to address food insecurity often with “invading” neighborhoods with top-down approaches where “white knowledge” is presumed to be the correct knowledge. Social justice is narrowed to increasing “participation” while ignoring power, ownership, and decision-making control. Justice-rooted efforts emphasize both entrepreneurial opportunities and health education, however, these activities are geared towards building economic independence at the individual- and community level. However, efforts are stymied by historical trauma and trying to build community wealth in a neoliberal capitalistic market.

It is helpful to disentangle these “roots” to see the ways in which white privilege can impede social justice efforts, even with good intentions, for as McClintock [11] aptly argues, community gardens can encompass multiple contradictions ranging from perpetuating the neoliberal status quo to imagining the radical possibilities of “making a way out of no way”. However, McClintock [13] has also stated that “who” initiates these efforts may matter the most in terms of outcomes. Not to deliberately misunderstand McClintock, but this almost essentializes race – which is not conducive to working across difference if one is in a privileged position. Instead, Roman-Alcala [12] cautions those with privilege to listen first and act second. While this provides room for those with privilege to act in solidarity, there is little concrete detail as to what this looks like in practice, other than vague extortions that it takes time to build trust.

Further, Ramirez [21] has wondered if a black “urban imaginary of farming” might differ from a “rural black imaginary of farming” (p. 758). Scholars who have done studies specifically with black community garden leaders [10,21,41] have found that (1) they were all older (60+), most of whom have had experience with the Civil Rights movement; (2) came from the Deep South where agriculture was not solely pejorative, but also a way of life to promote self- and community-reliance; and, (3) worried that Black youth were losing their heritage due to oral stories of trauma (accurate) but without the direct experience of “growing” sufficiency, individual or collective. Ramirez [21] poignantly asks, to what extent has the Great Migration erased “alternative memories and relationships with the land” (p. 758)?

Research Purpose

The aim of this article is to describe the ways race plays a role in community gardens in the Deep South, given its history with slavery. The original purpose of this study was to explore community gardens in Alabama (a predominantly rural state in the Deep South) – largely because most of the research has focus on metropolitan areas in the Northeastern. Midwest, and Western parts of the US. However, like London et al., [26], race played such a prominent role that it made sense to focus on that aspect.

Methods

This study employed a qualitative approach to explore community gardens in Alabama. To recruit, a list of community gardens in AL was developed using online searches (i.e., Google, Facebook) and snowballing. The following contact information was collected: community garden name, location, and contact information (i.e., name, phone, email) as available. The initial list was vetted to ensure community gardens were still active (e.g., recent Facebook posts) and assess whether they were public, meaning anyone could join, based on information available online. Hospital, prison, and school gardens were excluded as these typically are only for a specific clientele and operate within institutions that are qualitatively different from civil society (e.g., grassroots efforts, nonprofits). The researcher then contacted each community garden contact, verifying active and public status and identifying the garden leader(s). Garden leaders were those who managed the day-to-day operations of the community garden. Of note, a military community garden was included in this study because, while only military personnel (and approved civilians) could access this garden, it was a large military base and the garden was located in a military neighborhood (i.e., base housing). In short, it was public to active and retired soldiers and their dependents.

Identified garden leaders were asked to participate in interviews conducted and recorded using Zoom and informed that questions would be around why the community garden started, how it operates, who tends to participate, and key challenges and successes. Specific prompts related to diversity and rural considerations were also included. Participants received $35 Amazon e-gift cards as an incentive. Snowballing occurred at the end of interviews. Recruitment occurred during summer 2024 using the Dillman method meaning potential recruits were not contacted more than three times and subsequent efforts (e.g., emails or phone messages) were more personalized. Based on this process, a total of 27 community gardens were identified that met criteria (19 online; 8 snowball). Ten garden leaders agreed to participate representing nine community gardens; response rate by garden was 33%. Interviews lasted an hour long on average, ranging from 40 mins. to 1.5 hrs. Qualitative data was transcribed, coded, and analyzed for themes [42]. Participants were provided study details during recruitment via email and/or phone. Study details were reviewed again at the time of interviews and participants provided verbal consent. IRB approval was obtained from Auburn University.

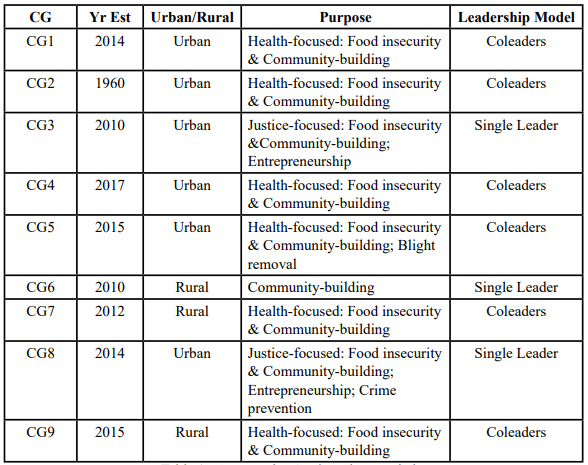

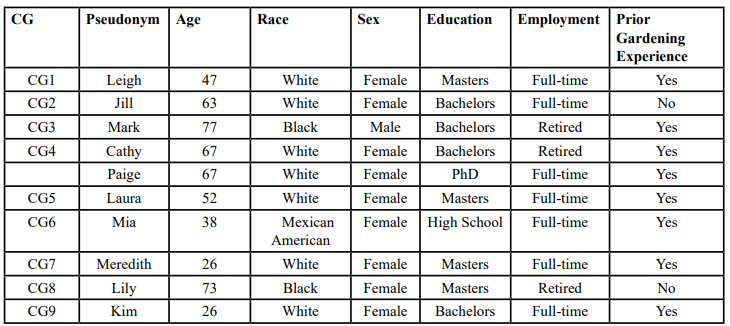

Of the nine community gardens, 33% (n=3) were in rural areas while the remaining 67% (n=6) were in urban areas. They were also well established; one began in 1960. Excluding that outlier, the other eight had been operating for 10.6 years on average, ranging from seven to fourteen years. Most community gardens (67%) had a co-leadership model (e.g., multiple garden leaders and collective decision-making). With respect to the garden leaders, the majority were women (90%), white (70%), worked fulltime (70%), and highly educated: 40% had bachelor’s degrees and 50% had master’s degrees or higher. The average age was 53.6 years, ranging from 26 to 77 years old, and 80% had grown up with gardening to some degree (see Tables 1 & 2).

Results

Results are organized using the theoretical framework of health focused and justice-focused efforts and leadership: (1) health focused efforts and white leadership and (2) justice-focused efforts and BIPOC leadership. Notably, there were no market-focused community gardens. These “roots” are indeed difficult to disentangle in practice; however, white leaders were involved with primarily health-focused efforts while BIPOC leadership were involved with primarily justice-focused efforts. In each of these broad themes, issues of race will be discussed, specifically motivations and purpose, the presence or lack of racial diversity, and the degree to which white privilege and/or historical trauma has played a role in these efforts.

Health-focused Efforts & White Leadership

Community gardens led by white leaders had a focus on addressing health issues, food insecurity, and community building – although, the degree of emphasis on each of these did differ. For example, Paige, a nurse who felt so strongly about health, explained that starting a community garden was to prevent cardiovascular disease.

And cardiology is my background. I would see, you know, when people have cardiac disease as an adult. You know… it’s a disease. We can treat it, but the best way to handle it is to prevent it. It made sense that… particularly with fresh organic produce, you know, that we grow ourselves can have a huge role in improving our health. The other thing is, I figured out, well, things are improving so much in cardiovascular disease. We're going to cure cardiovascular disease. People are going to live longer. So, they're going to have to have food to eat, so I better figure out how to grow food for myself and for others – Paige (White, 67)

All shared a desire to address food insecurity, but there were no grand claims of bringing good food to others largely for practical reasons. Most of these community gardens were simply places where people could rent a plot and grow food for themselves and their families. Laura, especially, was very careful to stress that the purpose of her community garden was blight removal and not overstate the ability of their community garden to provide food to those in need.

But because we were a blight removal, and because I work, you know. We needed people to maintain their own beds, so everybody grows their own food, and they have to maintain their own bed … like we couldn't. I couldn't. I can't maintain their beds for them, so we weren't. We're not. There is a, there is another model in (urban area) where some or one person grows food, and then just shares it. Ours is a model where you grow for yourself. And then you feed your family or your household. – Laura (White, 52)

One community garden was communal where volunteers grew produce to donate to various food banks, rather successfully, over 2,000 lbs. of produce was donated the previous year. However, most of these community gardens operated under the model of “grow for yourself” and sharing extra produce was informal via social media announcements and boxes left out for people to take as they wished.

Parry and colleagues [43] have stated that “community gardens may be more about community than they are about gardening” (p. 180) and this study was no different. By far, the main desire or purpose of the community garden was to build community. Often inspired by other efforts they had heard about, community gardens were viewed as a “neat” idea that was feasible and a positive way to bring people together. Leigh shares a story that is illustrative of this point.

The idea came about from community members, and there was a mill in town that was just vacant. And so, it’s just piece of land in the middle of town. And so, they came up with the idea to start a community garden and rent out the plots…. And so, people had heard about it... and they're like, that's a neat idea to bring the community together…But the first, like founding people were like - some of them were just civic people and some were like master gardeners and stuff like that. So, it was just a bunch of random people who came together and started it. – Leigh (White, 47)

There was little evidence of a “missionary zeal” of bringing good food to others in top-down approaches in these efforts. Perhaps because most of these community gardens were not associated with large nonprofits. All had nonprofit status (e.g., 501c3) mostly to obtain small grants and receive donations (e.g., seeds, plants, etc.) from businesses (e.g., tax write-off); however, these community gardens developed based on a small group of people with land not being used (e.g., vacant lots) or donated (e.g., church land). As such, they were reliant on community buy-in and engagement to start a community garden. All shared stories of having multiple community meetings to discuss if people wanted a garden there, how it should operate, and how to get involved. Similarly, all hosted community events to maintain engagement such as workdays, seed swaps, festivals, and workshops.

Race & Racial Diversity

Despite these many attempts to be inclusive and engage the community, garden leaders in urban areas admitted that it was predominantly older, white, middle-class women involved. Cathy (White, 67) joked saying “we are predominantly old ladies”. Granted, racial diversity is a function of the neighborhood; however, these community gardens were in areas that leaders reported to be racially and socioeconomically diverse and yet, the garden did not reflect the community.

I mean, it's a fairly diverse neighborhood where as far as (urban area) goes, but as far as our specific garden. Yeah, it's more age diversity than race/ethnic diversity. I mean, we've had. We've had African American gardeners before. – Laura (White, 52)

As Leigh described it, “most of us can buy our overpriced produce at Publix” and that they “would love for those people who need the vegetables to come to us and volunteer and harvest their own”. Admittedly, transportation could be an issue for some of these gardens; however, one community garden was located right next to a predominantly African American church who, despite proximity to racial diversity, had not been successful in engaging them thus far.

The core group is very… not diverse, and we've tried to work on that, like right next to our church is an African American church. We've invited them in. Every once in a while, we'll get a volunteer from there, you know their groundskeeper like keeps, I mean, you know, mows the grass right up to the garden, and we, you know we've tried to invite them in and let them know. You know they're welcome to come over, and if anybody's in need they can get. But they really just don't want to participate, you know, if that makes sense and they're right there. Um. It just is. – Leigh (White, 47)

When asked why, garden leaders were puzzled over the difficulty of building relationships across race in the garden, stating that it “just is” and that they keep “trying”. Saldana’s concept of white viscosity may help explain these results; however, these garden leaders seemed to intuitively understand that racial representation was important if they wanted to the community garden to feel welcoming to diverse racial groups. They consciously “imported racial diversity” by bringing in diverse racial groups and organizations for volunteer events, such as the Boys and Girls club, Bridge Builders, and so on. Historical trauma may also play a role here. Notably, white-led community gardens in rural areas did not report any challenges with racial diversity stating that it was a “pretty healthy mix” and about “50/50 in terms of White and Black gardeners”. It seems possible that agriculture and growing is viewed more positively in rural areas than they might be in urban areas.

Historical Trauma

The issue of slavery came up explicitly for one garden leader, Paige, who was much more aware of why bridging across race could be challenging. Her community garden model was interesting because it involved community gardens she and her co-leaders were directly managing as well as mentoring other community gardens who asked for their help. Thus, she could provide a broader perspective about racial diversity across her city.

“Unfortunately, in our area…There is a lot of racial divide. We've worked very hard to break that barrier. And it has come from, you know, it's come from some deep rooted ideas on… in both directions. We have a lot to do to break down these racial barriers and you just have to plug away at it and recognize that it's there, you know? And the garden is a great place to teach that; this garden doesn't care if you're white, black, old, young, green, yellow, LGBTQ. It doesn't care. It's gonna love you if you love it.” – Paige (White, 67)

One community garden they work with is in a youth center that primarily serves Black youth in a low-income urban neighborhood. While gardening with youth, Paige was told by residents that “only slaves do that!” Troubled by this, Paige reported taking time to pause and reflect. She also highlighted a conundrum that white allies face. One the one hand, they are told that “there's not enough community gardens in African American communities. We're not engaging them” referencing critiques of white privilege. On the other hand, they are told that “when we encourage gardening, particularly with children, you're encouraging children to pursue a vocation of agriculture or gardening, then you're taking them away from vocations that would earn them more money.” Her solution to this dilemma was to highlight and celebrate Black agricultural knowledge.

“Oh, my gosh! I need to rethink this. So, we did. We had a period where we did a freedom garden. I had read, there was a place, I think, either Louisiana or Mississippi. They grew what was called a freedom garden, and it was, they grew things that the slaves would have eaten because their rations were minimal, and so, to supplement their rations, they would either forage or that some of them brought seeds over from their native African communities, their areas. They would braid them in their hair or and so, some of those, some of the things that we have now in our gardens actually came from slaves bringing them to America. So, we did a freedom garden one time, and we introduced the children to the, to the impact that African Americans, particularly in our state, with George Washington Carver and all the all the groundbreaking work that he did… – Paige (White, 67)

Paige went on to share other efforts they continue to do with Black youth, all of which highlight BIPOC folk as knowledgeable leaders. Perhaps that is why she does not hear comments of “slavery” any more at that location and that the community garden is more supported by residents. Indeed, celebrating BIPOC agricultural knowledge seems to be crucial in building trust across race rather than “importing racial diversity” to simply labor in the garden which could be viewed as culturally insensitive.

Justice-Focused Efforts & BIPOC Leadership

Community gardens led by BIPOC leaders had a focus on health and food insecurity, community building, and entrepreneurship – although, similarly, the degree of emphasis on each of these differed. One anomaly was Mia whose primary goal was community building. Given that her community garden was on a military base, this made sense as this is a highly transient population. For her, the community garden was a place to welcome and orient newcomers; increasing food access while beneficial was secondary and entrepreneurial efforts did not make sense since military personnel were already employed.

The other two community gardens were in low-income, predominantly Black urban neighborhoods led by Black leaders who had grown up in the neighborhood, had substantial experience with community organizing and policy advocacy, and were established leaders of their community. Interestingly, while both emphasized healthy eating and entrepreneurship, the way these community gardens operated were almost diametrically opposed, especially when it came to views of “charity”. For example, Lily started her community garden to prevent crime stating that they “were known as the most crime-riddled community in the State of Alabama. We would have at least one murder every month in my neighborhood” that has since evolved into feeding the community due to health concerns.

So, when I got involved with the food crisis in the neighborhood, because the people my age were dying out from probably eating too much of pork and eating everything they said we're not supposed to eat, and all the stuff we're not supposed to drink. We eat and drink it, anyway. So, I got on this soapbox to try to improve the health and the eating patterns of people, as well as stopping the crime in the community… Gonna have to do a community garden and let everybody know this is for anybody in the community who needs food. – Lily (Black, 73)

In short, Lily started a communal garden where she and core volunteers grew food for the neighborhood. Entrepreneurial efforts were largely paying stipends, based on grant availability, and youth skill development, such as having youth sell produce at a farmers’ market. Remarkably, community-building has been successful where more “eyes on the street” has reduced crime to where they have not had a “murder in the past ten years”.

Alternatively, Mark, an economist, viewed the community garden as a “community-building intervention” to provide viable pathways out of poverty to promote self- & community-sufficiency. He started with a “typical” community garden that rented individual plots for nominal fees. It has evolved into a hybrid community garden and urban farm that grows “value-added” products that can be sold to restaurants and farmers markets providing a viable source of income to growers. For Mark, charity did not make sense economically, nor did it provide a way to make a living for those doing the growing.

I'm not a big giveaway type of organization. It's fine. I mean, there's nothing wrong with it. It's just that you can't be sustainable giving everything away. You just can't last. You'll run out of money and I’m an economist first when it comes to this kind of thing. And so, you can decide to grow it, or you can decide to encourage somebody else to grow it and buy it from them. So, my system is more on the side of encouraging folks by giving them some money to add to their sufficiency to do this. – Mark (Black, 77)

Now, Mark was sensitive to food access and poverty. To be more economically sustainable, individual plot fees had grown from $25 to $250. But then, Mark stated, “how do I deal with folks in poverty?” Mark’s solution was to implement a sliding scale based one people’s income and accepting SNAP benefits when selling their produce. However, Mark was still faced with the challenge of being profitable (via urban farming efforts) to have the financial resources to pay growers to produce value-added products until they were financially solvent on their own. In short, Mark needed to make enough of a profit to provide the capital and resources (e.g., be the bank) to help “incubate” entrepreneurship, as well as maintain current operations. This challenge aligns with previous studies where justice-oriented efforts faced the same difficulties.

Race & Racial Diversity

Despite being “of the community,” BIPOC leaders also had challenges with racial diversity in their community gardens. Mia, again, was another anomaly. She had inherited the military community garden, meaning she agreed to take over leadership when the previous person was stationed elsewhere. For Mia, the lack of racial diversity was due to its location – it was where the officers’ lived and not where enlisted personnel lived (officer vs enlisted housing are typically segregated). In the US, officers must have a college degree which, due to historic and structural white privilege, officers tend to be white and affluent whereas enlisted personal tend to be more racially and socioeconomically diverse. Mia also shared her experience feeling unwelcome in garden-related events off-base that were predominantly white.

Everywhere I go, I noticed it, but I guess I really don't talk openly too much about it. Because generally it is Caucasian older women. So, I've been going to the seed swaps outside of the installation, and I get a table. And I actually was talking to my friend, and I always tell them. I'm the only freaking person with any melanin in this area, and not just that. I was the youngest person there because of… And I'm not gonna lie. Some of them, I don't think I was welcomed too much, and they knew I was a service member. I'm like, I'm here. The same interests, same love as you guys…But I have not been welcomed in all the places I've been representing the community (garden) which is sad. – Mia (Mexican American, 38)

Indeed, Mia went on to share that she actively seeks racially diverse community gardens to promote representation and wonders what a higher visibility would do for youth of color. She even highlighted another BIPOC led community garden that participated in this study as an example.

I was like, there's not a lot of community gardens, but that is a community garden run by people of color. So, you guys could see that not only the white community is part of this. I'm like, there's a lot of people, a lot of diversity. Well, not a lot of diversity. But we exist, too, you know. – Mia (Mexican American, 38)

As for the other two Black leaders, both stated that it was difficult for them to engage their own community. Indeed, they were unable to do so consistently unless “something was in it for them” meaning they received payment. For Mark, this was very disappointing and somewhat perplexing.

My experience when it comes to diversity support is, I get more support from the majority (white) community than I get from the minority (black) community. It's hard, because it's more disappointing for me being of color to say that than anything else. I can't. Okay. Like, I get a lot of support from majority churches than minority churches. – Mark (Black, 77)

When asked if he thought poverty might be related to the lack of racial diversity, Mark thought that being in poverty would “encourage you to do more”. That is, why wouldn’t you grow your own food to reduce food costs and if you could, sell some to make extra income? Lily, on the other hand, while expressing disappointment did not seem surprised, instead she relied on her faith to keep her going; however, given her age, her fears around sustainability seemed justified.

It's been an interesting journey, trying to figure out how to maintain a garden. Now I've done it for 10 years and I'm about burnout. And I've had 2 or 3 different groups saying they were gonna help me, and I haven't seen any help yet. Everybody helping me with the prayer but manpower. If you don't have anything in place to make it continue and you just have a person like me, one person, 73 years old. How much longer can I provide this for the community? I'm not sure. And my spirits are really low on this… So, when you're working in a low-income neighborhood. Just remember the story of what Jesus said when he healed 10 lepers. One person came back and told Jesus, thank you. So, if one person comes back and says, thank you, be grateful. – Lily (Black, 73)

Historical Trauma

When asked if they thought the history of slavery might have anything to do with the lack of racial diversity and community engagement, Mark and Lily had very different responses. Mark appeared to be dumbfounded by the thought, pausing to reflect, before stating that “No, I can't say that's it. I can't really make that connection.” Lily, on the other hand, reported hearing comments about gardening being viewed “as slavery,” especially among youth of color. However, Lily indicated that she has only heard that comment “Oh, this is slave labor” from justice-involved youth doing community service hours in the garden, reminiscent of “stinking thinking” from other studies [10].

And that group, which the reason they have to do community service is because they broke the law. Those were the groups saying, “This is slave time work you got me doing.” See? They're thinking is different from the ones who have not broken the law. They're thinking differently. – Lily (Black, 73)

Lily, who tended to speak in parables, then shared a story of taking in a teen girl who needed community service hours for her probation. Lily then worked with the judge to have the teen girl’s hours count as double so she could meet her hour requirements by end of summer. This teen girl worked with other non-justice involved youth, who, according to Lily were “typical” and able to show the teen girl “normal behavior”. Nevertheless, at the end of the summer, every child received a certificate and a goodie bag, except for the justice involved teen girl.

I did not give her anything because she was a community service worker. She had to be there to get her hours. She started crying. And the other kids, all of them got around and started hugging her. And that was a surprise to me... She was just a normal kind of person to them…And one of the guys who's a volunteer said, ‘Well, I don't think it's right.’ I said, ‘Listen. She is a thug. She has to work off her time. That's the problem now, her mom and her dad, all of them, let her do what she wanted to do. That's why she’s in the trouble. I said, you don't know what she did, and I'm not gonna tell you.” – Lily (Black, 73)

Is this an example of harsh consequences, internalized oppression, or restorative justice? It is unclear. What is clear is that Lily only heard the comment “Oh, that’s like slavery” from justice-involved youth who had grown up in environments where breaking the law was the norm and there was a sense of entitlement rather than a value for individual hard work, which could be daunting to engender in the face of structural poverty and racism.

Still, despite their discrepant reactions to the question of slavery as an impediment, both Mark and Lily shared that they grew up with farming – it was a way of life. Indeed, even though both were now in “urban” areas, it was not long ago when their community had gardened or had animals (e.g., chickens, cattle) to support the community. Mark, especially, was concerned that his community was losing touch with their heritage and knowledge.

What you got is most households generationally don't know how to cook. Households with…one, two, three generations in it and nobody really knows how to cook. All they can do is go to the grocery store and buy things that they can warm up, or they will get to fast food. And you would think that community gardens in low-income communities in Alabama would be stronger than the ones in urban areas. That base knowledge of how to cook and grow is there. But in general, most folks have never seen their food harvested before you. [We are making] some assumptions about Alabama [because it is a rural state] that don't hold up.

The concern in losing this heritage and skill aligns with previous studies where Black gardeners noted that they used to have gardens throughout the neighborhood growing up, but they seem to have disappeared [21,41]. This hints at the “rural imaginary” that Ramirez [21] spoke of where agriculture may not be viewed negatively given the close history of farming as a way to survive, provide, and even thrive. The decline in gardening knowledge did not appear to be solely a BIPOC concern. A white-led community garden in a rural area had also noticed a similar decline in generational gardening knowledge. That is, younger people did not seem to know how to grow food for themselves, despite growing up in a rural area.

They've never planted anything or any, you know it's just them learning how to do it. Just kind of teaching them, cause they never done it before, whether it's planting vegetables at the garden or it's I didn’t grow up with it. It was definitely something like, “we don’t know how to do that”. – Kim (White, 26)

Discussion

Despite being an exploratory study with a convenience sample, both white and BIPOC folk were involved in community gardens (urban and rural) in the Deep South. Both struggled with racial diversity but for different reasons. White-led gardens tended to be health-focused; however, they did not appear to employ “top down” approaches as previous studies have found. The lack of racial diversity might be better attributed to culturally insensitive practices (e.g., importing racial diversity). BIPOC-led gardens also struggled with the same issue. However, interpretations of “justice-efforts” were not monolithic and interpretations varied in terms of charity, entrepreneurship, and perceptions of historical trauma. Still, Black leaders did not equate gardening with slavery. Perhaps this is because Black leaders were older (e.g., Civil Rights era) and had grown up with agriculture to support their community (e.g., plot/plantation). Indeed, the common element across these gardens was the fear of losing food and farming knowledge, particularly among youth. Future research should explore if there is a “generational” viscosity as suggested by Ramirez [21] and incorporate theories and histories from other BIPOC groups (e.g., Indigenous, Asian, Hispanic/Latinx). Given the exploratory nature of this study, it would be presumptuous to provide policy recommendations. The author can only echo previous scholars who have advocated for community land trusts to promote democratic community-based economic development [18]. In terms of social work practice, celebrating BIPOC agricultural knowledge and contributions appears to be crucial to building trust across race, especially for those with white privilege. This point cannot be emphasized enough. Community gardens are approachable and romanticized. As such, they attract a wide range of individuals who want to come together to grow and garden together. Given the current climate of division and fear, social workers can use these interventions to build relationships that cross difference to help birth a world based on understanding our shared humanity.

Competing Interests:

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

Hume, C., Grieger, J. A., Kalamkarian, A., D’Onise, K., & Smithers, L. G. (2022). Community gardens and their effects on diet, health, psychosocial and community outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 1247. View

Alqurashi, E. (2019). Predicting student satisfaction and perceived learning within online learning environments. Distance Education, 40(1), 133-148. View

Teig, E., Amulya, J., Bardwell, L., Buchenau, M., Marshall, J. A., & Litt, J. S. (2009). Collective efficacy in Denver, Colorado: Strengthening neighborhoods and health through community gardens. Health & Place, 15(4), 1115-1122.View

Okvat, H.A., & Zautra, A.J. (2011). Community gardening: A Parsimonious path to individual, community, and environmental resilience. American Journal of Community Psychology, 47, 374-387.View

Draper, C., & Freedman, D., (2010).Review and Analysis of the Benefits, Purposes, and Motivations Associated with Community Gardening in the United States. Journal of Community Practice,18(4). View

Raneng, J., Howes, M., & Pickering, C. M. (2023). Current and future directions in research on community gardens. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 79, 127814. View

Ferris, H., Bongers, T., , de Goede, R. G. M., (2001). A framework for soil food web diagnostics: extension of the nematode faunal analysis concept. Applied Soil Ecology,18(1),13-29. View

Guitart, D., Pickering, C., & Byrne, J. (2012). Past results and future directions in urban community gardens research. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 11(4), 364-373. View

Milburn, L.A.S., & Vail, B.A. (2010). Sowing the seeds of success: Cultivating a future for community gardens. Landscape Journal, 29(1), 71-89. View

Jettner, J. F. (2017). Community gardens: Exploring race, racial diversity and social capital in urban food deserts. Virginia Commonwealth University, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, 10274649. View

McClintock, N. (2013). Radical, reformist, and garden variety neoliberal: Coming to terms with urban agriculture’s contradictions. Local Environment: The International Journal of Justice and Sustainability. View

Roman-Alcalá, A. (2015). Concerning the unbearable whiteness of urban farming. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, 5(4), 179-181. View

McClintock, N. (2018). Urban agriculture, racial capitalism, and resistance in the settler‐colonial city. Geography Compass, 12(6), e12373. View

Miller, T., et al. (2012) Ethics in Qualitative Research. 2nd Edition, SAGE Publications Ltd., London. View

Hawthorne, C. (2019). Black matters are spatial matters: Black geographies for the twenty‐first century. Geography Compass, 13(11), e12468. View

Lipsitz, G. (2006). The possessive investment in whiteness: How white people profit from identity politics. Temple University Press. View

Loewen, J. W. (2007). Lies my teacher told me: Everything your American history textbook got wrong. Simon and Schuster. View

Riordan, M., & Rangarajan, A. (2024). Healing the racial divide in urban agriculture. In Planning for Equitable Urban Agriculture in the United States: Future Directions for a New Ethic in City Building (pp. 525-540). Cham: Springer International Publishing. View

Bullard, R. D. (2000). Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class, and Environmental Quality. 1990. Boulder: Westview. View

Flowers, C. C. (2020). Waste: One woman’s fight against America’s dirty secret. The New Press. View

Ramírez, M. M. (2015). The elusive inclusive: Black food geographies and racialized food spaces. Antipode, 47(3), 748 769.View

McCutcheon, P. (2019). Fannie Lou Hamer's Freedom Farms and Black agrarian geographies. Antipode, 51(1), 207-224. View

White, M. M. (2011). Environmental reviews & case studies: D-town farm: African American resistance to food insecurity and the transformation of Detroit. Environmental Practice, 13(4), 406-417. View

Bradley, K., & Herrera, H. (2016). Decolonizing food justice: Naming, resisting, and researching colonizing forces in the movement. Antipode, 48(1), 97-114. View

McCutcheon, P. (2013). “Returning home to our rightful place”: The Nation of Islam and Muhammad Farms. Geoforum, 49, 61-70. View

London, J. K., Cutts, B. B., Schwarz, K., Schmidt, L., & Cadenasso, M. L. (2021). Unearthing the entangled roots of urban agriculture. Agriculture and Human Values, 38(1), 205 220. View

Hinrichs, C.C., & Allen, P. (2008). Selective patronage and social justice: Local food consumer campaigns in historical context. Journal of Agriculture and Environmental Ethics, 21(4), 329-352. View

Alkon, A.H., & McCullen, C.G. (2010). Whiteness and farmers markets: Performances, perpetuations…contestations? Antipode, 43(4), 937-959. View

Pudup, M.B. (2008). It takes a garden: Cultivating citizen-subjects in organized garden projects. Geoforum, 39(3), 1228-1240. View

Allen, P. (1999). Reweaving the food security safety net: Mediating entitlement and entrepreneurship. Agriculture and Human Values, 16(2), 117-129. View

Hoover, B. (2013). White spaces in black and Latino places: Urban agriculture and food sovereignty. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, 3(4), 109-115. View

Guthman, J. (2011). “If they only knew”: The unbearable whiteness of alternative food. In A.H. Alkon & J. Agyeman (Eds.), Cultivating food justice: Race, class and sustainability (pp. 263-281). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. View

Ghose, R., & Pettygrove, M. (2014). Urban Community Gardens as Spaces of Citizenship. Antipode, 46(4), 1092-1112. View

Meenar, M.R., & Hoover, B.M. (2012). Community food security via urban agriculture: Understanding people, place, economy, and accessibility from a food justice perspective. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, 3(1), 143-160. View

Reynolds, K. (2014). Disparity despite diversity: Social injustice in New York City’s urban agriculture system. Antipode. View

Crossney, K.B., & Shellenberger, E. (2012). Urban food access and the potential of community gardens. Middle States Geographer, 44, 74-81. View

Agyeman, J. (2005). Sustainable communities and the challenge of environmental justice. New York, NY: New York University Press.View

Taylor, D. (2011). The Evolution of environmental justice activism, research, and scholarship. Environmental Practice, 13(4), 280-301. View

Kato, Y. (2013). Not just the price of food: Challenges of an urban agriculture organization in engaging local residents. Sociological Inquiry, 83(3), 369-391. View

Slocum, R. (2006). Anti-racist practice and the work of community food organizations. Antipode, 38(2), 327-349. View

Reese, A. M. (2018). “We will not perish; we’re going to keep flourishing”: Race, Food Access, and Geographies of Self Reliance. Antipode, 50(2), 407-424. View

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. View

Parry, D.C., Glover, T.D., & Shinew, K.J. (2005). ‘Mary, Mary quite contrary, how does your garden grow?’: Examining gender roles and relations in community gardens. Leisure Studies, 24(2), 177-192. View