Journal of Social Work and Welfare Policy Volume 3 (2025), Article ID: JSWWP-139

https://doi.org/10.33790/jswwp1100139Research Article

A Qualitative Evaluation of Suicide Prevention Course Implemented in the USCG: Results from focus groups of USCG members and affiliates

Brooke A. Heintz Morrissey1,2, Adam K. Walsh1,2, Jennifer K. Bivin1,2*, Sama W. Elmahdy1,2, Miranda C. Meyer1,2, Peter M. Gutierrez4, Marta E. Denchfield3, Paul E. Bertrand4, and Joshua C. Morganstein1,2

1 Center for the Study of Traumatic Stress, Department of Psychiatry, Uniformed Services, University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD, 20814, United States.

2 Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Inc, Bethesda, MD, 20817, United States.

3 United States Coast Guard, CG-1111 Behavioral Health Services

4 LivingWorks

Corresponding Author Details: Jennifer K. Bivin, Research Assistant, Department of Psychiatry, Center for the Study of Traumatic Stress, Uniformed Services University, 4301 Jones Bridge Road,Bethesda, MD 20814-4799, United States.

Received date: 03rd March, 2025

Accepted date: 02nd April, 2025

Published date: 04th April, 2025

Citation: Heintz Morrissey, B. A., Walsh, A. K., Bivin, J. K., Elmahdy, S. W., Meyer, M. C., Gutierrez, P. M., Denchfield, M. E., Bertrand, P. E., & Morganstein, J. C., (2025). A Qualitative Evaluation of Suicide Prevention Course Implemented in the USCG: Results from focus groups of USCG members and affiliates. J Soci Work Welf Policy, 3(1): 139.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Lack of knowledge in suicide intervention and mental health stigma continue to be significant issues within the military, in that they act as hindrances towards providing and seeking help. This project addresses these issues by evaluating the applicability of the safeTALK suicide prevention training in the United States Coast Guard (USCG) population. This project served as an addition to a larger quantitative analysis that observed the effects of the training for trainers (T4T) model on skill retention in participants that participated in Living Works’ safeTALK suicide prevention training course. To provide a different perspective, this project took on a more qualitative approach that focused on participants' experiences with safeTALK itself. Data was collected through virtual focus groups with USCG members and affiliates from both the East and West coasts. Participants ranged in age, rank, geographical location, as well as the times at which they took the safe TALK training. Results revealed that participants’ opinions were slightly mixed, but most agreed that the training was beneficial in teaching them new skills and is applicable to the USCG and its mission. Additionally, participants emphasized the importance of addressing stigma towards help-seeking, providing high quality trainers, and implementing refresher courses. The results confirmed that learning safeTALK skills were seen as beneficial in the USCG community, and may, therefore, inform future training and provide suggestions for areas of improvement and course development.

Keywords: Suicide prevention, safeTALK, U.S. Coast Guard, Stigma, Qualitative Analysis

Introduction

Background

The United States Coast Guard

Established in 1790, the U. S. Coast Guard is a component of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, whose major role is to protect the safety, security, environment, and the economy of the United States. Its military structure, mission focused on humanitarian work, and its law enforcement authority puts the Coast Guard in a unique position within the federal government. Operationally, the Coast Guard supports the Department of the Navy during times of war, as well as ensures maritime safety and security, protects natural resources, and conducts essential search and rescue operations during times of peace. With approximately 40,000 active-duty members, around 7,000 reservists, and about 8,000 civilian employees, this diverse workforce allows the Coast Guard to effectively carry out its critical missions. With its unique blend of military and civilian workforce, the Coast Guard responds to a variety of emergencies, from natural disasters to counter-narcotics operations, while ensuring the safety and security of U.S. waters and facilitating international maritime trade. The phrase Semper Paratus (“Always Ready”) serves as the Coast Guard’s motto and describes concisely the agency’s mission and its increasing responsibility of protecting America’s safety, security, and economic well being [1]. “Coasties" is an informal term used to refer to members of the United States Coast Guard. It projects a sense of camaraderie among Coast Guard personnel (including active-duty members, reservists, and veterans). Coast Guard members, or Coasties, frequently share a strong community bond, emphasizing their commitment to service and teamwork in various missions, from search and rescue to safeguarding U.S. waters.

LivingWorks safeTALK Suicide Prevention Program

LivingWorks safeTALK is a training that is grounded in the adult learning principles developed by Knowles, Holton, and Swanson [2]. safeTALK training recognizes the unique needs of adult learners by respecting and incorporating life experiences into training (particularly through practice), addressing the real-life needs of trainees, and focusing on the development of skills through practice and feedback. The skills taught can be applied in any setting. It is the life experience of the trainees that provide the context for how those skills will be applied in specific settings, such as Coast Guard installations and ships. It is a half-day training aimed at increasing participants’ willingness and ability to recognize when a person might have thoughts of suicide, engage that person in direct and open talk about suicide, and move quickly to connect that person with someone able to provide a suicide first-aid intervention [3]. The program’s slogan, Suicide Alertness for Everyone, asserts that suicide safety is a responsibility shared by the whole community. In this study, that would be all Coast Guard personnel. safeTALK helps learners increase their alertness to suicide in everyday relationships and facilitate safe connections. Independent research conducted in multiple countries and settings consistently finds that safeTALK learners increase their willingness and ability to recognize when a person might be thinking about suicide and to engage in direct and open discussions with them about suicide [4-7]. One study demonstrated that post-training outcomes were maintained through six-month follow-up [5].

Gatekeeper Philosophy

This project utilizes the gatekeeper philosophy as a means to combat stigma and promote comfortability between Coast Guard members when discussing vulnerable topics, such as suicidal ideation. Gatekeeper training is built on the belief that through training, you can influence an individual’s knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes, which may result in that person being willing and able to help someone in need [8]. By increasing the number of people in a community who can recognize and appropriately intervene in the face of such problems, gatekeeper training ultimately aims to increase help-seeking behaviors in the community [9]. These trained helpers should notice when someone with whom they are interacting may be considering suicide, be knowledgeable about local resources to address the reasons why and help connect the person to those resources [10,11]. These helpers can be friends, family members, clergymen, family physicians, or any other trusted individual. Oftentimes, when a distressed person asks for help from a trained helper, they are turning to this individual because they trust them and are friends with them. It is not always the best policy to simply have the helper refer the distressed individual to a psychiatrist, as they will often choose not to follow up on the referral due to stigma or lack of trust in the mental health provider system. Theoretically, well connected networks of trained helpers and community resources make all members safer from suicide [12]. Therefore, training Coast Guard personnel in the evidence-based safeTALK program should lead to more Coasties noticing when their comrades may be in distress, helping to determine what specific type of help and support is most needed, and guiding them to those resources. This model is well suited to success in tight knit communities where members spend significant amounts of time working, living, and playing together.

Purpose

The USCG community continues to be a vulnerable population to suicide risk. This is due to several factors. First, the diverse nature of the Coast Guard’s missions requires a constant need for members to be ready to operate, deploy, and perform at high levels instantaneously. As a result, there is very little recovery time between missions and/or deployments. Secondly, Coast Guard members serve as the nation’s uniformed first responders, a population well-known to be at risk for adverse psychological consequences. As a result, Coast Guard members and families may experience an increased and even inescapable burden of stress. Third, there is a lack of awareness and readiness towards suicide prevention in the Coast Guard community, due in large part towards stigma towards prioritizing mental health. As a way to address these issues, the U.S Coast Guard Living Works Training for Trainers (T4T) project facilitated a roll-out of evidence-based suicide intervention skill training in Coast Guard populations, with a particular focus on mentoring and support of a select group of trainers. One of these trainings implemented by LivingWorks included safeTALK. This project aimed at observing the applicability of safeTALK and gatekeeper philosophy within the Coast Guard community, to help better understand how suicide prevention training can be implemented within the Coast Guard to maximize efficiency and effectiveness.

It is important to note, however, that while effective implementation is important, it is even more crucial to ensure that the training is helpful and relevant to the population it is serving, especially as it relates to a sensitive topic such as suicide. Thus, we chose to take a qualitative approach by conducting focus groups with Coast Guard members who had completed safeTALK training in the recent past. John Ward Creswell [13], a world-renowned scholar and founder of mixed methods research who has written 27 books detailing the importance of mixed method and qualitative research, indicates that the priority of qualitative research is to “achieve, as best as possible, understanding -- what he describes as a deep knowledge of some social setting or phenomenon” (1988). In order to achieve that understanding, more time needs to be spent interacting with the participants. Utilizing focus groups where we engaged in dialogue and discussion with the participants left us with a large amount of rich qualitative data in the form of transcripts. We were able to hear from participants regarding their experiences, perspectives, and ideas for future direction in a way that a traditional survey or numerical response could not capture. Using qualitative analysis, we were able to gain a deeper understanding of participants’ attitudes about the training, and participants were able to share personal anecdotes to further support their points. Participants’ answers were rooted in their own ideals and surrounding context that gave us a more holistic interpretation and perception of what the participants meant to convey.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Participants consisted of both trainers and trainees of LivingWorks’ safeTALK suicide prevention program. Both active-duty USCG members, and civilians affiliated with the USCG, such as spouses and civilian personnel, were interviewed. Participation was purely voluntary and anonymous, and all participants provided a verbal assent to have the interviews recorded and transcribed. USCG member participants ranged in age, ethnicity, and rank, as well as in geographical location. The date on which participants took safeTALK also ranged, with some participants having taken the course one year prior to the focus group, while others only a couple months. Participants were spread across seven virtual focus groups, with three groups and ten participants total representing trainees located on the West Coast, and four groups and 22 participants total on the East Coast. Interviews were conducted on both Coasts to observe any differences in how the safeTALK training was delivered, both logistically and content-wise. Examples of logistical differences include those in methods of training distribution (how did participants become aware of the training?) and types of trainers (USCG member or civilian). Examples of content differences primarily include those in trainer style, such as whether a trainer prefers a more presentation based or discussion-based approach.

Materials

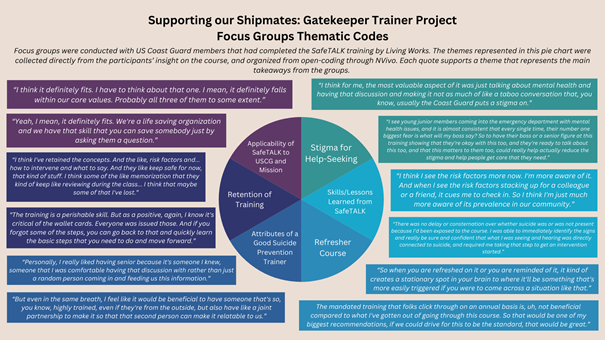

The Google Meets platform was used to conduct all focus groups. The NVivo (version 14.23.0) qualitative data analysis software was used to conduct thematic coding and analysis of the focus group transcripts. The online design platform, Canva, was used to create a pie chart (see Figure 1) for visual representation of the final themes. The pie chart was created for manuscript purposes only. Additionally, as this project is categorized as program evaluation and quality improvement, it was funded through operational and management funds.

Procedure

Data was collected through virtual focus groups led by a researcher on the team. All focus groups followed an open-ended interview format and ran for one hour. The following six questions were asked during each group:

1. Since taking safeTALK, how has your thinking changed about suicide risk and/or about how people might ask for help?

2. Since taking safeTALK, have you used any of the skills you learned with someone in distress or to help another safeTALK trainee/gatekeeper?

3. How does safeTALK fit within the Mission of the Coast Guard?

4. How knowledgeable and prepared was your safeTALK trainer? What did they do to make you feel comfortable to participate? If nothing, what do you wish they had done?

5. What is the most critical thing that Coasties can do to help fellow Coasties deal with thoughts of suicide?

6. How much of the information you learned in safeTALK have you retained, to date?

Each interview was recorded and transcribed through the Google Meets transcription feature. Once the aggregated focus group recording was transcribed, it was immediately deleted.

Data analysis was conducted through NVivo. All seven transcripts were first uploaded into NVivo, with one research assistant analyzing the East Coast transcripts, and another analyzing the West Coast transcripts. The process for thematic coding and analysis was the same for both sets of transcripts. The first step was for both research assistants to read through their respective transcripts while keeping the following themes in mind:

1. Applicability of safeTALK to the USCG mission

2. Retention of training due to safeTALK trainer attributes

Next, the research assistants used NVivo’s manual coding feature to highlight and code any words and phrases that were considered applicable to the aforementioned themes. These words and phrases were labeled as “references” in NVivo, and were then grouped into new, more broad themes according to their relevance to each other. Relevance was determined by several different factors between the research assistants, such as saliency, depth level, and applicability. Saliency refers to how often the references were brought up by participants. For example, when discussing attributes of safeTALK trainers, participants on both Coasts provided many specific examples of attributes they did and did not find to be beneficial, such as membership within the USCG, and a presentation-based approach, respectively. This was significantly helpful in creating one of the final themes “Attributes of a Good Suicide Prevention Trainer”, in that the research assistants were able to clearly recognize that this theme was a contributing factor to how participants received and retained information. Depth level refers to how much detail participants provided in their answers. For example, the issue of stigma within the USCG community towards discussions of mental health and suicide was brought up multiple times throughout interviews. More specifically, participants described the worry that many Coasties felt towards discussing mental health with their senior members, out of fear that they would be risking their position, or would be reprimanded. These details helped shape the creation of the “Stigma for Help-Seeking” theme. Finally, the factor of applicability refers to how participants’ answers related to the two aforementioned themes. For both the East and West Coast transcripts, a total of 13 themes each were developed, with each theme being supported by multiple references. The research assistants then merged the data for both coasts, by determining which themes were found across both sets of transcripts, and, therefore, best represented the data. Themes that only consisted of one or two references, or were only applicable to one focus group, were disregarded.

Results

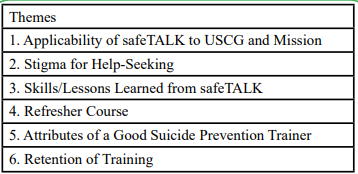

After the thematic analysis and merging process was complete, six themes were developed to represent the main takeaways from both coasts. The themes can be seen in Table 1 below.

Theme 1: Applicability of safeTALK to USCG and Mission

After introducing safeTALK training to the USCG, one of the most important factors to understand is how applicable the program was to the Coast Guard and its members. Participants discussed the applicability of the training, and some noted that suicide prevention doesn’t necessarily need to be tailored as it is a universal skill. There were mixed reactions to the level that participants found the training applicable to USCG life. For example, some participants noted that the example scenarios used in their training sessions were more civilian- focused, while other participants’ stated that their sessions incorporated more military-focused scenarios. However, most agreed that the training was applicable and fit well with the mission. One participant noted that, “Yeah, I mean, it definitely fits. We're a life saving organization and we have that skill that you can save somebody just by asking them a question”.

Theme 2: Stigma for Help-Seeking

Stigma surrounding seeking mental health treatment continues to be a significant barrier not only for civilians, but especially for Coasties. This theme represents the effects that stigma for help-seeking had on participants’ perspectives and receptivity to the safeTALK training. Many participants emphasized their appreciation that the training allowed them to openly discuss mental health. There was also discussion surrounding fear of reprimand caused by stigma when regarding junior members. One participant stated: “I see, um, young junior members of all branches coming into the emergency department with mental health issues, and it is almost consistent that every single time, their number one biggest fear is what will my boss say?...”.

Theme 3: Skills/Lessons learned from safeTalk

SafeTALK training emphasizes the importance of participants not only bringing awareness and recognition to signs of suicidality but adopting the role of a connector who is able to connect those who are struggling to further support. Therefore, it was crucial to discuss with participants the skills they learned from taking the course. Many participants stated that safeTALK helped them feel more confident in approaching peers who they think are showing risk factors. In doing so, participants felt that the skills learned through safeTALK encouraged them to stay vigilant towards recognizing potential risk factors. One participant stated: “It made my response to the situation immediate. There was no delay or consternation over whether suicide was or was not present because I'd been exposed to the course. I was able to immediately identify the signs and really be sure and confident that what I was seeing and hearing was directly connected to suicide, and required me taking that step to get an intervention started”.

Theme 4: Refresher Course

The importance of implementing a refresher course was also discussed amongst participants. Participants shared that a refresher course would be beneficial, although there was discrepancy in how exactly that refresher course should be implemented in terms of course length and repetition of the course. The skills that are taught through safeTALK are crucial and should be revisited to maintain that knowledge. One participant expressed this sentiment and emphasized the benefits of refreshing the learned skills, “So when you are refreshed on it or you are reminded of it, it kind of creates a stationary spot in your brain to where it'll be something that's more easily triggered if you were to come across a situation like that”.

Theme 5: Attributes of a Good Suicide Prevention Trainer

Previous literature [14] supports that people are more willing to confide personal and vulnerable matters, such as thoughts of suicide, with peers and those who are able to create an open and welcoming presence. Therefore, it was important to hear from participants how they perceived their safeTALK trainers, and if any specific attributes stood out to them in either a positive or negative light. There were mixed opinions on whether participants felt that it was more beneficial for their trainers to be USCG members or not; some stated that they felt more comfortable being trained by a senior USCG member, as they felt a sense of familiarity, while others mentioned that having a civilian trainer provided an outside perspective that was useful when it came to such a sensitive topic. Many emphasized, however, that regardless of USCG membership, it was appreciated when trainers were welcoming, knowledgeable, and encouraged group discussion. One participant stated: “But even in the same breath, I feel like it would be beneficial to have someone that's so, you know, highly trained, even if they're from the outside, but also have like a joint partnership to make it so that that second person can make it relatable to us”.

Theme 6: Retention of Training

A significant factor of any course or training is how well the information is retained. It is important to understand how much information and which parts of the course are remembered. Participants admitted that the skills learned in the training are perishable and need to be maintained. However, they also noted that although they might not remember all the specifics of the course, the main ideas and takeaways are retained. One participant detailed their personal experience with retention of the course material by saying, “I think I've, uh, retained the concepts. Yes. The, um. And the like, risk factors and how to intervene and what to say [...] I think some of the, like, memorization that they kind of keep like reviewing during the class. Um, I think that maybe some of that I've lost.”

The themes were then organized into a pie chart (see Figure 1) for visual representation through Canva. The research assistants determined which references most saliently represented each theme and chose two of these references to assign to each theme on the pie chart.

Overall, it can be noted that the USCG members were thoughtful and delivered insightful commentary on this training course. They are cognizant of the stigma surrounding mental health in their organization and recognize the importance and value of suicide intervention programs such as safeTALK in breaking down this barrier. In line with this, participants alluded to the idea that open, casual discussions surrounding mental health amongst peers, as well as between senior and junior members are not considered a norm within the community. According to the Coasties, the course emphasized the prevalence of suicide in their communities and how best to intervene when necessary, which is important to them as the USCG is a lifesaving organization.

Discussion

In this study, focus groups were conducted with members and affiliates of the USCG for the purpose of gaining rich information on their experiences and perspectives on the safeTALK suicide prevention training by LivingWorks. The findings suggest that successful implementation of a suicide prevention training such as safeTALK within the USCG community may require (1) a significant amount of investment and involvement from all USCG members, primarily senior members, (2) an incorporation of in-training scenarios that can be applied to real-life situations that occur within the USCG community, and (3) an emphasis on not only learning the skills, but practicing and utilizing them over time.

As supported by theme 5, “Attributes of a Good Suicide Prevention Trainer”, many participants emphasized the importance of involving senior members in the implementation and participation of safeTALK training. As such, leadership buy-in is a crucial component to ensuring both high participation and quality of trainers. First, senior members could act as spearheads for the implementation of safeTALK, as their investment and interest would promote participation for the training, bringing interest and higher prioritization to safeTALK’s message and importance. When respected senior members are seen taking a role in spreading awareness for a cause not widely discussed in the USCG community, such as discussion of suicide, all members of the community may feel a greater sense of confidence and comfort in joining them. Second, leadership buy-in would aid in improving the quality of resources put into safeTALK, therefore resulting in the distribution of a better and stronger training program. This is especially crucial because it presents a tangible solution to an existing disconnect between leaders simply stating that they care for Coasties’ wellbeing and putting the concept of care into practice. More specifically, when Coast Guard members are sent on missions that negatively impact their well beings, it is difficult for them to feel that care. By emphasizing the importance of distributing safeTALK throughout the USCG, senior members would be placing leverage on the operational implementation of the program, and therefore raising the standards for the quality of resources being allocated towards it. As one of these resources includes safeTALK trainers, senior member involvement would increase mindfulness when selecting them and help ensure that highly qualified people are chosen to conduct the training.

Regarding the training itself, the findings that support theme 1, “Applicability of safeTALK to USCG and Mission”, highlight the importance of maintaining applicability towards the USCG within safeTALK. This does not mean that safeTALK must be fully tailored for the USCG, as the skills it teaches are universally applicable, however, many participants expressed that they appreciated when the training incorporated scenarios to which Coast Guard members could relate. As such, it is important that Coasties feel a sense of connection to the training, so that they may feel more confident in using the skills in their day-to-day lives. Because it is difficult on an operational level to create a training program that is fully tailored to the USCG, it may be beneficial for the USCG to work with a group such as LivingWorks to create a program that fully complements the experiences of the Coast Guard. This could be accomplished through pre-training meetings between LW Training and Delivery staff and the identified USCG trainers to talk through how to use the flexibility built into the safeTALK trainer manual to ensure better relevance to Coastie learners. In the meantime, safeTALK trainers may disclose to participants that although some of the scenarios in the training may not be directly applicable to their experiences, they are to be used as a base for learning the skill, and once the skill is learned, it can be applied to a more applicable situation. By doing so, safeTALK trainers can establish a connection between themselves and the Coast Guard members without changing the training itself. This lets Coasties know that safeTALK trainers are aware of the very specific and nuanced experiences that Coasties may undergo and are willing to make the training more applicable to them. Requiring additional preparation and senior leadership support, facilitated discussions could be held with each cohort of learners to discuss skill application in USCG-specific settings.

Both senior involvement and emphasizing USCG applicability in safeTALK implementation would also aid in increasing training retention. As seen in many of the themes, participants discuss that although they remember key points of the safeTALK training, they have difficulties retaining all of the skills learned. Consequently, many participants stated that they were not able to utilize these skills outside of the training environment. This pattern results in a lack of fidelity towards sustaining skills among participants and weakens the impact of the training. The findings suggest that training retention may be improved through senior members promoting training participants to set aside time to practice safeTALK skills in real-life scenarios, as well as to participate in refresher courses. More importantly, the community as a whole must feel invested in the implementation of safeTALK. By establishing a connection between safeTALK trainers and participants, training retention can further be improved, as Coasties will feel a greater sense of drive towards sustaining safeTALK skills, when they feel that these skills can be applied to real-life situations.

Conclusions

The United States Coast Guard faces a growing challenge in relation to mental health, with an average of eight suicides per year. Implementing programs such as safeTALK allows us to work towards addressing this issue. This raises an important question: are we measuring success strictly in terms of suicide reduction, or are we aiming to foster a broader shift towards openness, help-seeking, and stigma reduction? We have heard from participants that this program was extremely helpful in providing them with more comfort around the idea of suicide in their communities and equipping them with the skills necessary to begin an intervention with a peer in need. SafeTALK aims to engage service members in conversation about mental health in a way that empowers them to support each other in their day-to-day, creating an environment where servicemembers feel comfortable seeking help from a peer, as opposed to exclusively from mental health professionals. That seems to be a good and reasonable indicator of effectiveness for a program such as safeTALK, rather than requiring that decreases in suicide rates are the metric.

SafeTALK translates the Coast Guard’s commitment to caring for its people from principle to practice. It provides structured and repeatable key steps and skills that can be taught to anyone. When safeTALK is implemented effectively, these life-saving skills are no longer vague and complex, but rather they become actionable and standard, allowing participants to normalize supportive behaviors. However, as with any learned skill, it is important to provide opportunities for reinforcement and maintenance of these skills. Without regular practice, these intervention skills can diminish and thus it is crucial to ensure additional training courses are available to provide reinforcement.

Currently, there is not a proper infrastructure in place at the Coast Guard that would allow for continued, comprehensive training of mental health intervention skills. We heard from participants that they believe it is necessary for refresher courses to be available, and for there to be a larger infrastructure that can span across the United States. SafeTALK was successfully implemented, but to meet the need of continued education, this project would need to be scaled up to become an enduring program at the Coast Guard. Program management resources would need to be increased and the Suicide Prevention Program structured to support adequate staffing, technology resources, and training capability ensuring. To support long term change in the culture around mental health help-seeking, it is critical that organizational structure be adaptable to support the needs of a suicide prevention training across all levels of the United States Coast Guard.

Future Directions

To advance suicide prevention efforts in the U.S. Coast Guard, establishing a collaborative workgroup that incorporates both the East coast and West coast would allow for facilitated collaboration and unity in approaching next steps. By bringing together key leaders from all organizational levels, a best strategy can be developed similar to the Suicide Prevention and Response Independent Review Committee (SPRIRC). Relative to other military organizations, the Coast Guard is unique in that it is small in size. Therefore, it would be feasible to incorporate and involve the top ten leading figures in the formulation of a committee and the execution of a proper enduring suicide prevention strategy and program. Given their leadership roles in the Coast Guard, they are also the most equipped to know what would work best within their organization.

Declaration of Competing Interests:

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests’.

Acknowledgements:

The authors wish to thank the United States Coast Guard, LivingWorks, Lena Gavello, and USCG MSST Ted Brandt for their contributions to this study.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the Department of Defense (DoD), Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USU), and/or the United States Government.

References

Caliber Associates, Inc. (2005). 2004-2005 U.S. Coast Guard childcare needs assessment: Final report. View

Knowles, M. S., Holton, E. F., & Swanson, R. A. (2005). The adult learner: The definitive classic in adult education and human resource development. Elsevier. View

Living Works Education. (2016). safeTALK trainer Manual (Version 2.2). Living Works Education. View

Bailey, E., Spittal, M. J., Pirkis, J., Gould, M., & Robinson, J. (2017). Universal suicide prevention in young people: An evaluation of the safeTALK program in Australian high schools. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 38(5), 300–308.View

Holmes, G., Clacy, A., Hermens, D. F., & Lagopoulos, J. (2021). Evaluating the longitudinal efficacy of safeTALK suicide prevention gatekeeper training in a general community sample. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 51, 844–853. View

Kinchin, I., Russell, A. M. T., Petrie, D., Mifsud, A., Manning, L., & Doran, C. M. (2020). Program evaluation and decision analytic modelling of universal suicide prevention training (safeTALK) in secondary schools. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy, 18(2), 311–324. View

Mellanby, R. J., Hudson, N. P. H., Allister, R., Bell, C. E., Else, R. W., Gunn-Moore, D. A., Byrne, C., Straiton, S., & Rhind, S. M. (2010). Evaluation of suicide awareness programmes delivered to veterinary undergraduates and academic staff. Veterinary Record, 167(19), 730–734. View

Wong, J., Brownson, C., Rutkowski, L., Nguyen, C. P., & Becker, M. S. (2014). A mediation model of professional psychological help seeking for suicide ideation among Asian American and White American college students. Archives of Suicide Research, 18(3), 259–273. View

Wyman, P. A., Brown, C. H., Inman, J., Cross, W., Schmeelk Cone, K., Guo, J., & Pena, J. B. (2008). Randomized trial of a gatekeeper program for suicide prevention: 1-year impact on secondary school staff. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 76(1), 104. View

Burnette, C., Ramchand, R., & Ayer, L. (2015). Gatekeeper training for suicide prevention: A theoretical model and review of the empirical literature. Rand Health Quarterly, 5(1). View

Isaac, M., Elias, B., Katz, L. Y., Belik, S. L., Deane, F. P., Enns, M. W., Sareen, J., & Swampy Cree Suicide Prevention Team. (2009). Gatekeeper training as a preventative intervention for suicide: A systematic review. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 54(4), 260-268.View

Hawgood, J., Woodward, A., Quinnett, P., & De Leo, D. (2022). Gatekeeper training and minimum standards of competency: Essentials for the suicide prevention work force. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 43(6), 516–522. View

Creswell, JW. (1998). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design Choosing Among Five Traditions. Sage Publications, Inc. View

Snyder, J. A. (1971). The use of gatekeepers in crisis management. Bulletin of Suicidology, 8, 39-44.