Journal of Social Work and Welfare Policy Volume 3 (2025), Article ID: JSWWP-145

https://doi.org/10.33790/jswwp1100145Research Article

Perceived Helpfulness of Formal and Informal Supports among Collegiate Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence

Hyunkag Cho, Ph.D, MSW1*, Jennifer Allen, MSW2, Abbie Nelson, Ph.D, MSW, LCSW3, and Kaytlyn Gillis, MSW, LCSW4

1,2,4School of Social Work, Michigan State University,655 Auditorium Road, 230 Baker East Lansing, MI, United States.

3Department of Criminal Justice, Social Work & Sociology, Southeast Missouri State University, Cape Giradeau, MO, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Hyunkag Cho, Ph.D, MSW, Associate Professor, School of Social Work, Michigan State University,655 Auditorium Road, 230 Baker East Lansing, MI, United States.

Received date: 09th April, 2025

Accepted date: 19th May, 2025

Published date: 21st May, 2025

Citation: Cho, H., Allen, J., Nelson, A., & Gillis, K., (2025). Perceived Helpfulness of Formal and Informal Supports among Collegiate Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence. J Soci Work Welf Policy, 3(1): 145.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Purpose: Intimate partner violence (IPV) among college students is a serious public health problem. Seeking help after IPV victimization is critically important to reducing negative consequences of IPV. The literature suggests that help-seeking does not always result in positive outcomes. This study identified the predictors of help-seeking outcomes, with special attention given to various types of help sources.

Methods: A cross-sectional online survey was conducted, with main variables being IPV victimization (physical, sexual, technological, psychological), help-seeking sources (seven formal, six informal) and outcomes (helpful or not), and depression. A series of logistic regression analyses were run with each source of help as the dependent variable.

Results: Among formal help sources, social workers were the most helpful (89%), with police (51%) the least helpful. Among informal help sources, friends were the most helpful (81%), with partner’s family (46%) the least helpful. Logistic regression analysis results showed that medical help was less likely to be helpful for those who were male, depressed, or victimized by technological violence, and friends were less likely to be helpful for those who were sexual minority or depressed.

Conclusion: Police being the least helpful among various help sources indicates a need for an in-depth look at how they interact with college student survivors. In medical care, male, depressed, or technologically victimized survivors may not receive a proper, sensitive care. Sexual minorities or depressed survivors found friends less helpful. Raising public awareness of less understood needs of various subgroups would help IPV survivors receive much needed help.

Keywords: intimate partner violence, help-seeking outcomes, formal help, informal help

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) among college students is a serious public health problem. IPV victimization during young adulthood, such as during the college years, is likely to lead to continuous victimization in adulthood, possibly throughout the lifetime [1,2]. IPV victimization not only affects college students’ health and academic outcomes [3-6], but also may result in ever-lasting, life-long trauma for the survivors and create various disadvantages that they may experience throughout the lifetime [6-8]. Seeking help from various sources after IPV victimization, including formal (e.g., police, doctor) and informal (e.g., family, friends) sources, is critically important to reducing such negative consequences [9,11]. The available literature, however, suggests that help-seeking does not always result in positive outcomes, and oftentimes negatively affects survivors’ well-being [11,12]. This study used survey data collected from college students across North America to identify the predictors of help-seeking outcomes, with special attention given to various types of help sources.

Collegiate IPV Survivors’ Help-Seeking

Studies examining help-seeking among collegiate IPV survivors have focused on help-seeking from a variety of formal and informal sources. Formal sources have included medical and legal services, mental health providers, shelters, law enforcement, and domestic violence hotlines [13-15]. Informal sources have included immediate and extended family, friends, partner’s family, coworkers, religious officials, and neighbors [13,14,16-18]. Overall, college students seem more likely to utilize informal sources after IPV victimization than formal sources. For example, in one study, 88.9% of collegiate survivors utilized informal sources of help, compared to only 23% who utilized formal sources of help [14]. Additionally, in a sample of college students who experienced physical IPV victimization, 25.1% of survivors utilized informal sources of help, compared to only 13.1% who utilized formal sources of help [15]. Further, in a sample of undergraduate students who experienced dating violence over four years, nearly 60% disclosed their experience to no one, 28.9% disclosed only to informal sources, and 13.5% disclosed only to formal sources [19]. While the prevalence of help-seeking among collegiate IPV survivors is generally low, when they decide to seek help, they appear more likely to seek informal sources of help than formal ones.

Predictors of Help-Seeking Outcomes

Researchers have examined IPV survivors’ perceived helpfulness of formal and informal sources of help. When a survivor seeks help, they might not always be satisfied with the services they use, or they might not perceive the service outcomes as helpful. Having a negative experience with a help source may make a survivor less likely to reach out for help later [20]. Furthermore, help-seeking is often associated with more severe or dangerous forms of IPV, such as severe levels of physical violence or threats of harm to children or dependents, [21]. Therefore, it is important to identify different predictors that may be associated with IPV survivors’ perceived helpfulness with different help sources, to identify what services might be best targeted to different survivors. A few studies have examined the perceived helpfulness of different help sources among cisgender female and male and transgender survivors of IPV. In a sample of transgender IPV survivors, more than half perceived the following help sources as helpful: LGBTQ organizations staff, friends, therapists or counselors, and survivor’s shelter staff [22]. On the other hand, less than half of the survivors perceived the following sources as helpful: hotline, attorney, parent or relative, medical doctor, and police [22]. Although each group represents both formal and informal sources, some findings are different from those among cisgender survivors. For example, in a sample of collegiate cisgender female survivors, a large proportion perceived their parents as the most helpful source of help [23]. Moreover, cisgender male IPV survivors in two studies perceived mental health services as helpful [24,25], while law enforcement, legal services, and services specifically targeted toward domestic violence survivors, such as hotlines, were perceived as unhelpful, perhaps because these services are traditionally targeted toward women [24,25].

Two studies examined IPV survivors’ perceived helpfulness of various help sources by race/ethnicity. Cho & Kim [26] found that Latino, Black, and White IPV survivors were less likely to perceive mental health services as helpful than were Asian IPV survivors. In another sample of female IPV survivors, Black/African American and Hispanic/Latina respondents were more likely to report the legal system as helpful than were White participants [27]. The authors speculated that perhaps due to various disparate treatment of people of color by the legal system, such as disproportionate arrests, inequitable sentencing, and culturally insensitive practices, women of color survivors had lower expectations of the legal system in helping them than did the white survivors, so they perceived the services as more helpful than the white survivors did [27].

IPV survivors’ perceived helpfulness of help-seeking sources also has been examined in the context of the survivors’ sexual orientation. A systematic review found that survivors of same-sex IPV victimization considered informal sources of help as a neutral form of help (not especially helpful or unhelpful), while many formal sources were perceived to be unhelpful [28]. Among gay male IPV survivors, the only help source that was perceived as helpful by more than half of the men (58%) was friends; the remaining sources, such as victims’ shelters and social workers, were largely perceived as not helpful to a little helpful [29]. In another sample of gay male IPV survivors, some help sources were considered to be a bit more helpful, such as 82% considering their friends to be helpful [30]. Additionally, 100% of the men considered a specific gay men’s domestic violence program to be helpful, demonstrating the importance of help sources that are tailored to survivors’ identities [30]. In research on help seeking of LGBTQ IPV survivors, around one third of survivor reported disclosing their experiences to a friend most commonly [31]. In times when they did not report their experiences, it was often due to survivors’ perception that their IPV experience was not bad enough [31].

Two studies examined differences in perceived helpfulness of services among IPV survivors with mental health conditions, in particular depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In the first study, being depressed was negatively associated with perceived helpfulness of all types of help-seeking [32]. The second study found that as male IPV survivors reported one additional negative help-seeking experience, they were 1.37 times more likely to meet the clinical cutoff for PTSD [24]. These results suggest that survivors with mental health conditions may have a more negative perception of help sources, and that perhaps these negatively perceived experiences adversely impact their mental health as well.

The type of violence that IPV survivors have experienced has been associated with their perceived helpfulness of services as well. For instance, in a sample of women who sought help from domestic violence agencies, those who experienced more control tactics in their abusive relationships perceived domestic violence agencies’ work regarding safety issues and child advocacy to be more helpful [33]. Moreover, in a community sample of female IPV survivors, reporting more instances of violent behavior (including nonphysical, physical, and sexual violence) was positively associated with the odds of finding a safety plan helpful, but inversely associated with the odds of finding leaving home to be helpful [34]. Additionally, among rural-residing female IPV survivors, the women were more likely to rate safety planning strategies as helpful if they had experienced more types of abuse, as well as if they had experienced psychological abuse [35]. Neither the duration nor the frequency of any type of abuse was significantly associated with female survivors’ perceived helpfulness of any particular help-seeking strategy [35]. These findings suggest that perceived helpfulness of help sources do differ based on the type of violence that IPV survivors have experienced, but more research is needed that includes men and women survivors, as well as includes newer forms of violence, such as cyber or technological violence.

The Current Study

The current literature suggests that collegiate IPV survivors are more likely to seek help from informal sources such as friends [14]. This differs, however, by demographic factors such as race/ ethnicity, gender identity, and sexual orientation. Additionally, results showed that collegiate IPV survivors’ perceived helpfulness of help sources varied by the type of help source, as well as personal health factors such as depression status. However, previous findings are inconsistent, and the studies had limitations in their methodology; they either relied on small samples, did not examine various types of IPV, or only focused on women. Our study strengthens the current literature by (1) collecting data from a large number of college students at multiple universities; (2) including multiple types of IPV; and (3) including both men and women in our sample, although the majority of the sample identified as women. The current study seeks to examine the following hypotheses: (1) Outcomes of collegiate IPV survivors’ help-seeking will be associated with survivors’ demographic characteristics, mental health, and type of violence experienced, and (2) the relationship among the outcomes of college IPV survivors’ help-seeking, survivors’ demographic characteristics and mental health, and types of violence experienced will differ by types of help sources.

Methods

Study Sample

We administered a cross-sectional online survey to undergraduate and graduate students at six universities in the U.S., including east coast, west coast, southern, and midwestern universities, and one in Canada during 2016 and 2017 (N = 4,723; citation hidden for anonymity). At each university, students were recruited using convenience sampling methods, for example via the Registrar, student mailing lists, and student organizations. At universities where incentives for research participation were allowed (5 out of 7 universities), participants could opt into a gift card raffle. The current study sample consists of 524 college students who reported any IPV victimization, sought help after IPV, and answered all major study questions. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of all participating universities.

Measures

IPV victimization: Four different types of IPV victimization were measured: physical, sexual, technological, and psychological victimization. Questions on physical and sexual violence were adapted from the Partner Victimization Scale. Questions on technological violence were adapted from Southworth et al. [36]. Questions on psychological violence experiences were adapted from Ansara & Hindin [37]. Participants were asked if they had ever experienced each type of violence perpetrated by a current or former romantic partner, such as boyfriends, girlfriends, husbands, or wives. A total of 12 items were used (Cronbach’s alpha [α] = 0.87). Four items were used for physical victimization (e.g., Not including horseplay or joking around, my partner pushed, grabbed, or shook me; α = 0.84). One item was used for sexual victimization (My partner made me do sexual things when I did not want to). Two items were used for technological victimization (e.g., My partner sent emails or text messages to threaten, insult, or harass me; α = 0.69). Lastly, five items were used for psychological victimization (e.g., My partner tried to limit my contact with family or friends; α = 0.81). Each item was scored based on a 4-point Likert scale that ranged from 0 (Never) to 4 (Four times or more). The sum of items of each of the four IPV types was obtained and dichotomized, with 0 meaning no victimization via a certain type of IPV, and 1 meaning having experienced some form of victimization of that type. Another variable was created to represent overall IPV victimization by adding all scale items together, and it was also dichotomized, so that 0 indicated no IPV victimization, and 1 indicated at least one experience of IPV victimization.

Help-seeking and outcomes: Participants who experienced at least one type of IPV victimization were asked: Have you talked about any of these incidents with any agencies or persons? Those who responded yes to this question were considered to have sought any help after IPV victimization. Among those who said they had sought any help, they were asked to identify which kinds of help they had utilized from a list of 13 help sources. Seven of the help sources (e.g., medical services, shelters, and police) were considered to be formal help sources, while six of the sources (e.g., family, friends, and coworkers) were considered to be informal help sources. On this list of 13 help sources, participants were asked to respond whether they had used that source (Yes) or whether they had not (No). Outcomes of help-seeking were assessed for those who had used at least one help source, with a yes/no item for each help source: Do you think the assistance you received was helpful?

Depression: Depression was measured using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale [38]. This scale consisted of 20 items that assessed how often during the previous week the participants had experienced symptoms of depression, such as restless sleep, poor appetite, or feeling lonely [38]. The 4-point Likert scale response options ranged from 0 (rarely or none of the time [less than 1 day]) to 3 (most or all of the time [5-7 days]). The reliability of the scale was 0.92. The score of each item was calculated and the sum of the items were obtained, ranging from 0 to 60. Following the convention that deems the scores of 16 or higher as clinically depressed [38,39], the sum was dichotomized: scores of 16 or higher as 1 (clinically depressed) and scores lower than 16 as 0.

Demographic characteristics: A number of demographic characteristics were assessed in the survey. Age was reported in years and treated as a continuous variable. Gender was assessed as “Female,” “Male,” or “Other.” Participants who chose “Other (e.g., transgender)” were excluded in the analyses due to the small number. LGBT identity (Lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender identity) was assessed with six response options (Heterosexual or straight, Gay or lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, Don’t know, Other) and dichotomized in this study as LGBT (Gay or lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, Other) or not-LGBT (Heterosexual or straight). Race was assessed with seven options: Asian/Pacific Islander, Black/ African American (non-Hispanic), Spanish/Hispanic/Latino, White/ Caucasian/European (non-Hispanic), American Indian/Native American/Native Canadian/First Nations, Multi-ethnic, and other, and recoded into three categories due to some small numbers (White, Non-White, and Multiracial).

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were obtained to report the sample characteristics and overall distributions of study variables: frequencies for categorical variables and means and standard deviations for continuous variables. A series of logistic regression analyses were run with each source of help as the dependent variable, with all other variables as the independent variables. Interaction terms with the type of IPV were entered in a subsequent model when any independent variable had a significant main effect. All analyses were conducted using SPSS v. 24.

Results

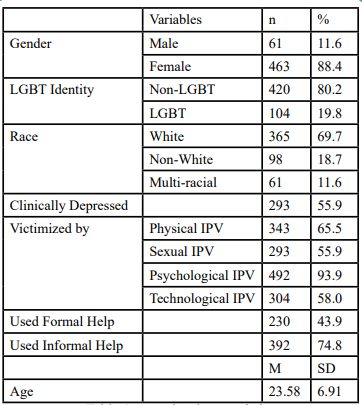

Sample characteristics are reported in Table 1. The majority of respondents were female (88.4%), non-LGBT (80.2%), and White/ Caucasian (69.7%). More than half of respondents were clinically depressed (55.9%). Respondents were aged 23.58 years on average. Psychological IPV was the most common type of IPV experienced by respondents (93.9%), followed by physical (65.5%), technological (58.0%), and sexual IPV (55.9%). Less than half (43.9%) of IPV survivors used formal help sources, while almost three quarters (74.8%) of survivors used informal help sources.

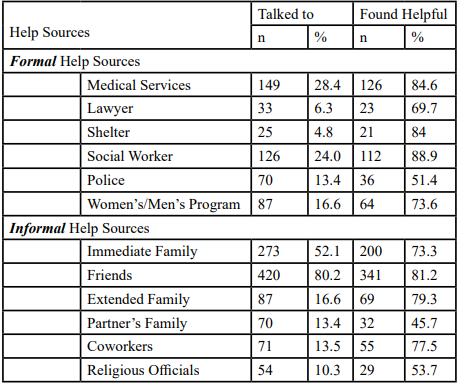

Table 2 shows the frequency of contact by respondents to different help sources as well as perceived helpfulness ratings for each of the help sources. The most commonly contacted sources of help related to the abuse of respondents were friends (80.2%) and immediate family (52.1%), while shelters (4.8%) and lawyers (6.3%) were the least commonly contacted sources of help. Of all the help sources, the most helpful perceived by those who used them were social workers (88.9%), medical services (84.6%), and shelters (84.0%), while partner’s family (45.7%), police (51.4%), and religious officials (53.7%) were perceived as the least helpful sources of support by those who used them.

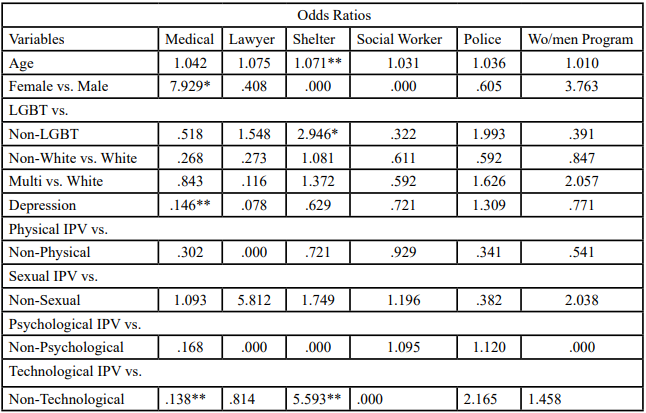

Table 3 shows a summary of logistic regression analyses for variables predicting the perceived helpfulness of formal help sources for survivors. For medical services, female survivors were nearly eight times as likely as male survivors to consider them helpful (OR = 7.929, p < .05); survivors who were depressed were less likely to consider them helpful than those who were not depressed (OR = .146, p < .01); and survivors who had experienced technological violence were less likely to consider them helpful than those who had not (OR = .138, p < .01). For shelter services, older survivors were more likely to consider them helpful than younger survivors (OR = 1.071, p < .01); LGBT survivors were more likely to consider them helpful than non-LGBT survivors (OR = 2.946, p < .05); and survivors who had experienced technological IPV were more than five times as likely to consider shelter services helpful than those who had not (OR = 5.593, p < .01). All interaction terms with IPV types were not significant.

Table 3: Summary of Logistic Regression Analyses for Variables Predicting the Effectiveness of Formal Help Sources Used by Survivors

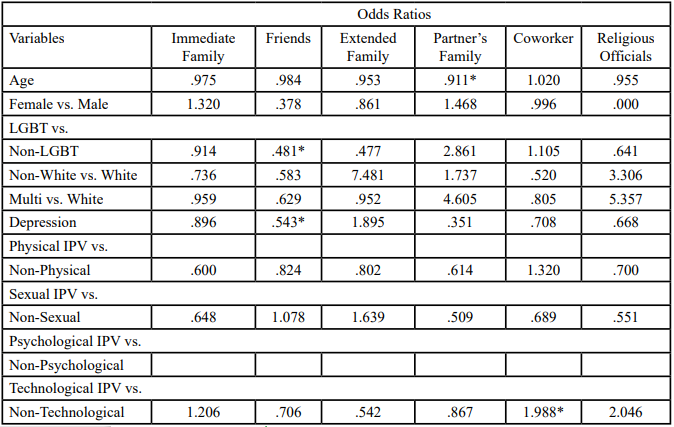

Table 4 shows a summary of logistic regression analyses for variables predicting the effectiveness of informal help sources used by survivors. For friends, LGBT survivors were less likely to consider them helpful than non-LGBT survivors (OR = .481, p < .05) as with those who were depressed (OR = .543, p < .05). For partner’s family, only age significantly predicted perceived helpfulness, with older survivors slightly less likely to perceive partner’s family as helpful than younger survivors (OR = .911, p < .05). Lastly, for coworkers, survivors who had experienced technological IPV were almost twice as likely to consider coworkers helpful than survivors who had not experienced technological IPV (OR = 1.988, p < .05). All interaction terms with IPV types were not significant.

Table 4: Summary of Logistic Regression Analyses for Variables Predicting the Effectiveness of Informal Help Sources Used by Survivors

Discussion

Our study results confirm that survivors rely more on informal sources of help than formal ones, which aligns with past studies on survivor help-seeking [14,15,19]. All informal sources, however, were not equal in their outcomes. While family, friends, and coworkers were found helpful by most survivors, their partner's family and religious officials were among the least helpful sources of support. This may indicate a need for an in-depth look at how these institutions and groups interact with college student survivors to leave such negative impressions. Although friends were mostly helpful, survivors affected by depression found them less helpful. This aligns with previous research that identifies that those who are depressed are less likely to perceive help-seeking helpful [32] and depression is associated with conflicts within friendships, especially in adolescence and young adulthood [40-42]. Given the literature that shows college students with depressive symptoms being more likely to report lower social support, including from friends [43,44] it is important to help informal help sources, such as friends and coworkers, recognize mental health problems suffered by survivors and provide affirmative support to survivors.

Additionally, LGBT survivors found friends less helpful than non LGBT survivors. Friends of LGBT survivors who are also part of the LGBT community may try to minimize or deny incidents of IPV within the community because of fear of confirming marginalizing stereotypes about LGBT relationships [45-47]. LGBT survivors may fear heterosexist or homophobic comments from their friend group, especially if they have previously experienced such comments (Scheer et al., 2020). Additionally, IPV is often viewed as an issue that only affects heterosexual relationships, so LGBT IPV survivors’ friends might not be able to help due to a lack of widespread information regarding IPV in LGBT relationships [31,47]. It is also possible that the perpetrator and survivor in LGBT relationships share the same group of friends within the LGBT community, especially in suburban or rural areas where LGBT groups may be particularly small, meaning that the survivor may be less willing to reach out to these shared friends for support [47,48]. More research is needed to understand the dynamics between friends and those with varying gender and sexuality and mental health status to explain why they may find this informal support less helpful. Raising public awareness of IPV dynamics and potentially less understood needs of gender and sexual minority survivors and those with depressive symptoms could help educate community members and lead to more IPV survivors receiving appropriate help from friends.

Formal help sources were utilized less frequently than informal ones, but most of them were found helpful by the survivors who used them (e.g., social worker, medical service, shelter). An exception to this was the police that were found to be the least helpful source of support. This is concerning because for decades the criminal justice system has become a key component of domestic violence interventions [49,50]. It has undergone many reforms over time, including stronger connections with community partners [51,52]. Despite this, our research suggests continued reforms until survivors feel it is a supportive entity from which to receive help.

Of formal help sources, medical care was considered mostly helpful, but there were disparities across gender, mental health, and IPV type; survivors who were male, depressed, or victimized by technological IPV were less likely to perceive them helpful. Male survivors may find the medical system not meeting their diverse needs or may be less likely to share about their victimization due to the shame that often surrounds male survivors of IPV [53-56]. Depressed survivors’ co-occurring needs may not be being addressed by the medical system leading to them not finding medical care helpful. Survivors of technological violence may find medical services less helpful due to less obvious medical conditions needing to be treated or lack of training about this type of abuse for medical care personnel to understand how to meet the needs.

While technological IPV survivors did not find medical services to be helpful, they did report shelters and coworkers as more helpful to them than those who didn’t experience this type of abuse. Shelters and workplaces may provide survivors with physical separation from perpetrators and relatively a safe place to rest and reflect. Future research is needed to explain why only technological IPV shows such an association, while other IPV types do not. This is especially true because other research has shown that it is common for other abuse types to be occurring in addition to the technological abuse [57]. Future research is encouraged to collect both quantitative and qualitative information of the contexts of survivors’ help-seeking, such as the type of support they received, specific outcomes of such supports, and the reasons for their dis/satisfaction with the services they used.

Compared to non-LGBT survivors, LGBT survivors were more likely to consider shelters helpful. Given the potential barriers to seeking formal help (e.g., medical care), such as stigma and structural inequities in the legal system [58], gender and sexual minorities may find them in a position in which shelters are one of the few backups for help. Although survivors in this study found shelters to be helpful, it is important to note that gender and sexual minority survivors have reported in previous research that services tailored towards their need are more helpful [59], which necessitates future research on the service provisions for LGBT survivors and their effectiveness. Future research may consider a rigorous recruitment of LGBT survivors and collecting data on their service use, its outcomes, and the contexts of help-seeking.

Study Limitations

This study contributes to the knowledgebase on the help-seeking outcomes for collegiate IPV survivors, but the findings must be considered within the context of some limitations. This study used a cross-sectional survey dataset that could not establish causal relationships, such as an effect of depression on help-seeking. The survey was self-reported and thus vulnerable to subjectivity. The study participants were recruited through convenience sampling; hence, results may not be generalized outside of the sample. The sample size was relatively small, especially for some categories of gender and race. A large majority of the sample were female, non LGBT, and white, which further limits the generalizability and points to the need for more research with more diverse samples. Moreover, rather than being measured separately, transgender identity and sexual orientation were measured under the same item, so people who identify as transgender and heterosexual/straight were in the same category as people who identify as cisgender and gay, for example. Lastly, IPV victimization was measured using four different types of victimization, some of which were measured only by one question (i.e., sexual IPV) or two (i.e., technological IPV). This might have resulted in the limited representation of a variety of victimization experiences.

Conclusion

Intimate partner violence is an ongoing public health problem among college students. Survivors do not always seek help; when they do, their well-being can be affected by the responses of the individual or system from whom they seek help [11,12]. This study revealed that help-seeking outcomes were associated with survivors’ demographic and mental health characteristics as well as with the type of IPV victimization. For example, LGBT survivors found shelters more helpful but did not perceive friends as helpful as non-LGBT survivors; depressed survivors reported friends and the medical system to be less helpful. Overall, partner’s families, police, and religious officials were among the least helpful sources of support. These results demonstrate that survivors’ needs and circumstances vary widely and that their experience with their choice of help source are likely to affect their future help-seeking behaviors. While social workers were noted as the most helpful of the formal support systems that survivors used, social workers need to continue to focus on appropriate training and interventions for survivors as they are among the frontline workers that interact with survivors [60].

Informal means of support have been reported to be the most relied upon by survivors. It is important to provide continued education for community members because at any time a survivor could be coming to a friend or family member for support. Furthermore, as technological IPV is increasingly prevalent, with social media often being used as a tool to instill abuse [57], knowledge of the many ways IPV can manifest can help others provide support when needed. This education could benefit from a focus on the diverse needs of survivors with mental health conditions as well as those identified as gender and sexual minorities.

Statements and Declarations: Authors do not have any financial or non-financial interests that are directly or indirectly related to this work submitted for publication.

Ethical Approval: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of all participating universities. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Availability of Supporting Data: The study data and the codebook will be available upon request.

Competing Interest:

Authors do not have any financial or non-financial interests that are directly or indirectly related to this work submitted for publication.

Funding: This study was not supported by any funding sources.

Author’s Contributions: Hyunkag Cho contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Hyunkag Cho. The first draft of the manuscript was written by all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

Greenman, S. J., & Matsuda, M. (2016). From early dating violence to adult intimate partner violence: Continuity and sources of resilience in adulthood. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 26(4), 293-303. View

Smith, P. H., White, J. W., & Holland, L. J. (2003). A longitudinal perspective on dating violence among adolescent and college-age women. American Journal of Public Health, 93(7), 1104-1109. View

Banyard, V. L., Derners, J. M., Cohn, E. S., Edwards, K. M., Moynihan, M. M., Walsh, W. A., & Ward, S. K. (2020). Academic correlates of unwanted sexual contact, intercourse, stalking, and intimate partner violence: An understudied but important consequence for college students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 35(21-22), 4375-4392. View

Brewer, N., Thomas, K. A., & Higdon, J. (2018). Intimate partner violence, health, sexuality, and academic performance among a national sample of undergraduates. Journal of American College Health, 66(7), 683-692. View

Klencakova, L. E., Pentaraki, M., & McManus, C. (2021). The impact of intimate partner violence on young women’s educational well-being: A systematic review of literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 0(0), 1-16. View

Wood, L., Voth Schrag, R., & Busch-Armendariz, N. (2020). Mental health and academic impacts of intimate partner violence among IHE-attending women. Journal of American College Health, 68(3), 286-293. View

Crowne, S. S., Juon, H.-S., Ensminger, M., Burrell, L., McFarlane, E., & Duggan, A. (2011). Concurrent and long-term impact of intimate partner violence on employment stability. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(6), 1282-1304. View

Pill, N., Day, A., & Mildred, H. (2017). Trauma responses to intimate partner violence: A review of current knowledge. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 34, 178-184. View

Renner, L. M., & Copps Hartley, C. (2021). Psychological well-being among women who experienced intimate partner violence and received civil legal services. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(7-8), 3688-3709. View

Wright, C. V., & Johnson, D. M. (2012). Encouraging legal help seeking for victims of intimate partner violence: The therapeutic effects of the civil protection order. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 25(6), 675-681. View

Laing, L. (2017). Secondary victimization: Domestic violence survivors navigating the family law system. Violence Against Women, 23(11), 1314-1335. View

Rich, K., & Seffrin, P. (2013). Police officers' collaboration with rape victim advocates: Barriers and facilitators. Violence and Victims, 28(4), 681-696. View

Barrett, B. J., Peirone, A., & Cheung, C. H. (2020). Help seeking experiences of survivors of intimate partner violence in Canada: The role of gender, violence severity, and social belonging. Journal of Family Violence, 35, 15-28. View

Cho, H., & Huang, L. (2017). Aspects of help seeking among collegiate victims of dating violence. Journal of Family Violence, 32, 409-417. View

Schramm, A. T., Swan, S. C., Fairchild, A. J., Fisher, B. S., Coker, A. L., & Williams, C. M. (2022). Physical intimate partner violence on college campuses: Re-victimization of sexual minority students and their help-seeking behavior. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services. View

Seon, J., Cho, H., Han, J.-B., Allen, J., Nelson, A., & Kwon, I. (2021). Help-seeking behaviors among college students who have experienced intimate partner violence and childhood adversity. Journal of Family Violence. View

Shumet, S., Azale, T., Angaw, D. A., Tesfaw, G., Wondie, M., Getinet Alemu, W., Amare, T., Kassew, T., & Mesafint, G. (2021). Help-seeking preferences to informal and formal source of care for depression: A community-based study in Northwest Ethiopia. Patient Preference And Adherence, 15, 1505–1513. View

Villatoro, A. P., Dixon, E., & Mays, V. M. (2016). Faith-based organizations and the Affordable Care Act: Reducing Latino mental health care disparities. Psychological Services, 13(1), 92–104. View

Mennicke, A., Coates, C. A., Jules, B., & Langhinrichsen Rohling, J. (2021). Who do they tell? College students’ formal and informal disclosure of sexual violence, sexual harassment, stalking, and dating violence by gender, sexual identity, and race. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 0(0), 1-28. View

Liang, B., Goodman, L., Tummala-Narra, P., & Weintraub, S. (2005). A theoretical framework for understanding help seeking processes among survivors of intimate partner violence. American Journal of Community Psychology, 36(1-2). View

Puente-Martínez, A., Reyes-Sosa, H., Ubillos-Landa, S., & Iraurgi-Castillo, I. (2023). Social support seeking among women victims of intimate partner violence: A qualitative analysis of lived experiences. Journal of Family Violence. Open access. View

Kurdyla, V., Messinger, A. M., & Ramirez, M. (2021). Transgender intimate partner violence and help-seeking patterns. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(19-20), NP11046- NP11069. View

Edwards, K. M., Dardis, C. M., & Gidycz, C. A. (2012). Women’s disclosure of dating violence: A mixed methodological study. Feminism & Psychology, 22(4), 507-517. View

Douglas, E. M., & Hines, D. A. (2011). The helpseeking experiences of men who sustain intimate partner violence: An overlooked population and implications for practice. Journal of Family Violence, 26, 473-485. View

Tsui, V. (2014). Male victims of intimate partner abuse: Use and helpfulness of services. Social Work, 19(2), 121-130. View

Cho, H., & Kim, W. J. (2012). Racial differences in satisfaction with mental health services among victims of intimate partner violence. Community Mental Health Journal, 48, 84-90. View

Ogbonnaya, I. N., AbiNader, M. A., Cheng, S.-Y., Jiwatram Negron, T., Bagwell-Gray, M., Brown, M. L., & Messing, J. T. (2021). Intimate partner violence, police engagement, and perceived helpfulness of the legal system: Between-and within-group analyses by women’s race and ethnicity. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research. View

Santoniccolo, F., Trombetta, T., & Rolle, L. (2021). The help seeking process in same-sex intimate partner violence: A systematic review. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. View

McClennen, J. C., Summers, A. B., & Vaughan, C. (2002). Gay men’s domestic violence: Dynamics, help-seeking behaviors, and correlates. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 14(1), 23-49. View

Merrill, G. S., & Wolfe, V. A. (2000). Battered gay men: An exploration of abuse, help seeking, and why they stay. Journal of Homosexuality, 39(2), 1-30. View

Sylaska, K. M., & Edwards, K. M., (2015). Disclosure experiences of sexual minority college student victims of intimate partner violence. American Journal of Community Psychology, 55(3-4), 326-335. View

Eubanks Fleming, C. J., & Resick, P. A. (2017). Help-seeking behaviors in survivors of intimate partner violence: Toward an integrated behavioral model of individual factors. Violence and Victims, 32(2), 195-209. View

Zweig, J. M., & Burt, M. R. (2007). Predicting women’s perceptions of domestic violence and sexual assault agency helpfulness: What matters to program clients? Violence Against Women, 13(11), 1140-1178. View

Hanson, G. C., Messing, J. T., Anderson, J. C., Thaller, J., Perrin, N. A., & Glass, N. E. (2019). Patterns and usefulness of safety behaviors among community-based women survivors of intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. View

Anderson, K. M., Renner, L. M., & Bloom, T. S. (2013). Rural women’s strategic responses to intimate partner violence. Health Care for Women International, 35(4), 423-441. View

Southworth, C., Finn, J., Dawson, S., Fraser, C., Tucker, S., (2007). Intimate partner violence, technology, and stalking. Violence Against Women. 13(8):842-56. View

Ansara, D.L., Hindin, M.J., (2010). Psychosocial Consequences of Intimate Partner Violence for Women and Men in Canada. J Interpers Violence. 26(8):1628-45. View

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. View

McDowell, I. (2006). Measuring health: A guide to rating scales and questionnaires (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. View

Bagwell, C. L., Bender, S. E., Andreassi, C. L., Kinoshita, T. L., Montareloo, S. A., & Muller, J. G. (2005). Friendship quality and perceived friendship changes predict psychosocial adjustment in early adulthood. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 22(2), 235-254. View

Helgeson, V. S., Wright, A., Vaughn, A., Becker, D., & Libman, I. (2022). 14-year longitudinal trajectories of depressive symptoms among youth with and without type 1 diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 1-10. View

La Greca, A. M., & Moore Harrison, H. (2005). Adolescent peer relations, friendships, and romantic relationships: Do they predict social anxiety and depression? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34(1), 49-61. View

Alsubaie, M. M., Stain, H. J., Webster, L. A. D., & Wadman, R. (2019). The role of sources of social support on depression and quality of life for university students. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 24(4), 484-496. View

Kugbey, N., Osei-Boadi, S., & Atefoe, E. A. (2015). The influence of social support on the levels of depression, anxiety and stress among students in Ghana. Journal of Education and Practice, 6(25), 135-140. View

Furman, E., Barata, P., Wilson, C., & Fante-Coleman, T. (2017). “It’s a gap in awareness”: Exploring service provision for LGBTQ2S survivors of intimate partner violence in Ontario, Canada. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services. View

Parry, M. M., & O’Neal, E. N. (2015). Help-seeking behavior among same-sex intimate partner violence victims: An intersectional argument. Criminology, Criminal Justice Law & Society, 16(1), 51-67. View

Scheer, J. R., Martin-Storey, A., & Baams, L. (2020). Help-seeking barriers among sexual and gender minority individuals who experience intimate partner violence victimization. In B. Russell (Ed.), Intimate Partner Violence and the LGBT+ Community. Springer. View

Bornstein, D. R., Fawcett, J., Sullivan, M., Senturia, K. D., & Shiu-Thornton, S. (2006). Understanding the experiences of lesbian, bisexual, and trans survivors of domestic violence. Journal of Homosexuality, 51(1), 159-181. View

Kim, M. (2020). The carceral creep: Gender-based violence, race, and the expansion of the punitive state, 1973-1983. Social Problems, 67, 251-269. View

Messing, J. T., Ward-Lasher, A., Thaller, J., & Bagwell-Gray, M. E. (2015). The state of intimate partner violence intervention: Progress and continuing challenges. Social Work, 60(4), 305-313. View

Barner, J. R., & Carney, M. M. (2011). Interventions for intimate partner violence: A historical review. Journal of Family Violence, 26(3), 235–244. View

Dobash, R. E., & Dobash, R. P. (2003). Women, violence, and social change. Routledge. View

Machado, A., Hines, D., & Matos, M. (2016). Help-seeking and needs of male victims of intimate partner violence in Portugal. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 17(3), 255-264. View

Taylor, J. C., Bates, E. A., Colosi, A., & Creer, A. J. (2021). Barriers to men’s help seeking for intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 1-28. View

Tsui, V., Cheung, M., & Leung, P. (2010). Help-seeking among male victims of partner abuse: Men’s hard times. Journal of Community Psychology, 38(6), 769-780. View

Walker, A., Lyall, K., Silva, D., Craigie, G., Mayshak, R., Costa, B., Hyder, S., & Bentley, A. (2020). Male victims of female-perpetrated intimate partner violence, help-seeking, and reporting behaviors: A qualitative study. Psychology of Men & Masculinities, 21(2), 213–223. View

Duerksen, K. N., & Woodin, E. M. (2019). Technological intimate partner violence: Exploring technology-related perpetration factors and overlap with in-person intimate partner violence. Computers in Human Behavior, 98, 223–231. View

Calton, J. M., Cattaneo, L. B., & Gebhard, K. T. (2016). Barriers to Help Seeking for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 17(5), 585–600. View

Edwards, K. M., Sylaska, K. M., & Neal, A. M. (2015). Intimate partner violence among sexual minority populations: A critical review of the literature and agenda for future research. Psychology of Violence, 5(2), 112–121. View

Crabtree-Nelson, S., Grossman, S. F., & Lundy, M. (2016). A Call to Action: Domestic Violence Education in Social Work. Social Work, 61(4), 359–361. View