Journal of Social Work and Welfare Policy Volume 3 (2025), Article ID: JSWWP-146

https://doi.org/10.33790/jswwp1100146Research Article

Public Health and Ecological System Approaches to Educating the Public about Suicide: Implementation and Evaluation of a Podcast on Suicide Prevention

Adam Walsh, PhD, LCSW, MSW1*, Brooke Heintz Morrissey, PhD, LCSW1, Miranda Meyer, MPA1, Rony Ngamliya-Ndam1, Benjamin Kruger1, Carol Fullerton1, and Joshua Morganstein1

1Department of Psychiatry, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda,MD, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Adam Walsh, PhD, LCSW, MSW, Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatry, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD, United States.

Received date: 07th March, 2025

Accepted date: 31st May, 2025

Published date: 02nd June, 2025

Citation: Walsh, A., Morrissey, B. H., Meyer, M., Ndam, R. N., Kruger, B., Fullerton, C., & Morganstein, J., (2025). Public Health and Ecological System Approaches to Educating the Public about Suicide: Implementation and Evaluation of a Podcast on Suicide Prevention. J Soci Work Welf Policy, 3(1): 146.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Introduction: In this paper, an educational podcast on the public health prevention of suicide is discussed. The inception, impetus, and background of the podcast are presented, along with the challenges and lessons learned.

The content of the podcast: Brain Hijack consists of multiple individual broadcasts about topics essential to public health prevention of suicide, such as asking for help, crisis intervention, lethal means safety, and lived experience. Each episode features cross-disciplinary perspectives offering unique insights into the current state of the field of suicide prevention, aiming to support a cultural shift by making the topic feel more approachable.

Dissemination and Results: The core themes of the podcast, including dispelling myths about suicide, dissemination outlets, and the podcast's reach, are presented.

Discussion: The utility, challenges, and next steps of disseminating a podcast series centered on the public health prevention of suicide are discussed.

Introduction

Over the centuries, the transmission of educational material has evolved significantly, transitioning from oral traditions to the adoption of written formats such as books, journals, and lectures. With the explosion of the internet, educational institutions have leveraged the opportunity to creatively distribute educational content to both academic and non-academic audiences. Since their inception in 2003, podcasts have experienced significant growth in popularity and usage.

Brain Hijack is an easily digestible podcast series compiling the most up-to-date insights and evidence on comprehensive public health approaches used nationally and globally to prevent suicide. The World Health Organization (WHO) names suicide as the third leading cause of death worldwide among 15- to 29-year-olds, citing stigma and taboo as major obstacles to prevention and intervention efforts [1]. Mental health-centered podcasts such as Brain Hijack offer accessible and discrete forms of internet-based intervention. Nonetheless, Brain Hijack differs from many existing mental health podcasts in that it is structured around the Six Core Pillars of suicide prevention, put forth by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Moreover, the inclusion of cross-disciplinary voices, a narrative style that blends expert insight with anecdotal experience, an emphasis on dispelling myths and common misconceptions, and a distinctive four-phase quality assurance process make it a markedly unique addition to the existing collection of mental health-related audio content. To be most effective, listeners would benefit from engaging with the entire podcast series, exploring a range of prevention strategies. Topics include peer support, crisis line access, safe messaging, and lethal means safety.

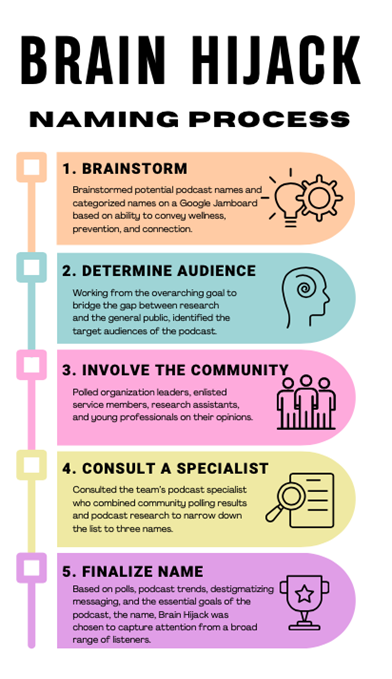

Formation of the Podcast Title

An important aspect of the podcast production process (see figure 5) is creating a long-standing name. To achieve this, the podcast team began by brainstorming potential podcast names and categorizing the names on a Google Jamboard, a digital whiteboard. The podcast team then identified the target audiences of the podcast. After identifying target audiences, organization leaders, enlisted service members, research assistants, and young professionals were polled to bridge the gap between research and the general public. The team then consulted their podcast specialist, Kristin Walker from Mental Health News Radio Network (MHNRN), who assisted in narrowing down the list to three names (the s word, shssh the silence, Suicide Prevention: science to practice). Finally, based on all the accumulated data, the name, Brain Hijack was chosen to capture attention from a broad range of listeners.

Review of Scientific Literature

Brief History of Podcasts + How Mental Health Podcasts Have Previously Been Used

In 2004, an estimated 1000 podcasts were available for use [2]. In 2022, approximately 75% of people of all ages expressed some familiarity with podcasts, with an estimated 1,000,000 podcasts available [2]. The growth of podcast production and consumption provides a useful opportunity for the mental health field to share information in a previously unconventional way.

One key function of podcasts is their ability to convey information that is not easily accessible to the general public. They have been used to communicate academic knowledge and unwritten rules in the scientific community that are typically not widely known [3]. This highlights the potential for mental health podcasts to reach non-academic audiences with valuable information [4]. For instance, podcasts can be used to share experiences of counseling sessions, information on mental health careers, and explanations of therapy interventions [4]. Providing such information in an accessible format is a crucial tool for increasing client interest and understanding. Lastly, podcasts are successful tools for providing supplemental medical information [4,5]. Overall, podcasts can serve as a vital tool for communicating previously inaccessible mental health information to the general public.

Why People Listen to Mental Health Podcasts

In addition to being able to share inaccessible information, it is also important that podcasts can attract and keep the audience. Some notable reasons listeners continue to tune into podcasts are due to the openness of the speakers, the discussion of firsthand experience with the podcast topic, and the relatability of the podcast [6]. In a study that investigated the appeal of ReachOut, an online mental health intervention that incorporates podcasts, participants noted that the honesty and openness of the speakers encouraged them to continue listening [7]. From these results, the ability to personally engage the audience is a clear advantage of mental health podcasts and provides a framework for podcasts to sustain audience engagement.

Who Is Listening to Mental Health Podcasts?

Additionally, an important consideration for mental health podcasts is understanding the demographics of the audience and their listening patterns. Current research supports that people with mental illnesses, people who had undergone treatment, and people with low education were more likely to listen to mental health podcasts [8]. Individuals with the lowest education benefited from podcasts the most, with higher ratings on items such as “learn new information”, “increase understanding of myself and my circumstances”, and “develop new ways of dealing with problems” [8]. These results reinforce the notion that mental health-oriented podcasts are an effective means of reaching listeners who otherwise may not have access to the quality resources necessary to understand and better manage their symptoms. In the absence of a universal healthcare system in countries like the United States, the importance of having ready access to the input of licensed mental health professionals cannot be overstated; this is especially significant considering the global prevalence of suicide. Future initiatives in the field may involve further tailoring content to the typical layperson, as Brain Hijack does, making difficult, and often complex, topics feel more approachable.

Participant Perceptions of Effectiveness

As the mental health field moves towards incorporating more online-based interventions, it is necessary to evaluate whether the audience views mental health podcasts as beneficial and meaningful. While evaluating the audience’s perceptions of the psychiatry podcast, PsychEd, researchers found that 100% of the participants rated the podcast as ‘helpful’ or ‘very helpful’ [9]. Researchers evaluating the mental health intervention podcast, ReachOut, reported that 81% of participants stated they would tell a friend about the podcast, indicative of their belief that it is worthwhile [7]. Both studies demonstrate a trend in the research to support that participants view mental health podcasts as beneficial and worthwhile.

Actual Measures of Effectiveness

In addition to perceived effectiveness, it is important to consider the measurable effectiveness of mental health podcasts. One way to measure a podcast’s effectiveness is in its ability to educate their audience. Researchers found that the most effective medical educational podcast utilized a podcast-like format by including interactive voice narration and a recorded simulation [10]. Additionally, when researchers compared outcomes of a standard educational online intervention to the podcast intervention, Operation Live Well, they found that higher short-term improvements were reported in Operation Live Well listeners [11]. Another measure of effectiveness is the ability of the podcast to decrease negative beliefs about mental illness. In 2011, researchers found that after listening to a podcast about cognitive therapy for psychosis, participants reported lower negative beliefs of auditory hallucinations and an increase in normalizing beliefs of paranoia after listening to the podcast [12]. This demonstrates that podcasts can serve as a tool to combat negative beliefs about mental illness. A final way to measure effectiveness is by determining if listeners acquire mental health-related tools after listening. Researchers found that after participants listened to the ReachOut podcast, 82% of listeners felt they learned more about mental health either ‘somewhat’ or ‘a lot’ [7]. Additionally, 69% of listeners felt they understood how to help others with their mental health either ‘somewhat’ or ‘a lot’ [7]. Both results demonstrate that podcasts can equip listeners with mental health skills and increase confidence in battling mental illness. However, the current literature lacks research on the long-lasting effectiveness of mental health podcasts. Current studies investigate short-term, cross sectional ffects of mental health podcast usage [10-12]; however, understanding long-term effects is necessary to ensure the viability of the podcast.

Limitations: the usage of podcasts to disseminate suicide-related topics

While current literature on mental health podcasts is gradually increasing, there is scant research on mental health podcasts about suicide. With increasing online campaigns of suicide awareness and prevention, it is important to explore how podcasts can serve as a valuable tool in the efforts to eliminate suicide. Brain Hijack is an educational podcast, hosted by Dr. Brooke Heintz Morrissey and Dr. Adam Walsh, that explores topics related to suicide prevention in an informational and accessible format. Brain Hijack utilizes a holistic public health approach that investigates a broad spectrum of topics within suicide prevention. Recently, FeedSpot.com ranked Brain Hijack among the top 31 suicide prevention podcasts worlwide at the time of this article. This paper aims to cover the development, implementation, and evaluation of the Brain Hijack podcast series and its public health-centered approach to educating the public about suicide prevention. Moreover, it explores how the podcast format is a useful means for disseminating emerging research, destigmatizing topics around suicide, and expanding the reach and accessibility of expert-informed mental health knowledge.

While offering valuable insight into the suicide prevention messaging at the core of the Brain Hijack podcast, this paper is not without its limitations. By not utilizing a formal study design, encompassing a control group, randomization, or quantitative data collection, the findings should be regarded as descriptive and exploratory in nature. Presenting the content of Brain Hijack in this manner helps establish a foundation for future research, but is not sufficient to draw causal inferences or generalizable results from. Future research might consider incorporating a more traditional experimental approach or mixed methods design to support expanding the growing body of literature on suicide prevention-focused podcasts.

Materials and Methods

To ensure suitability and appropriateness for publication, the Brain Hijack team implemented a four-point review process. The Senior Program Coordinator (SPC) conducted the first phase of the review process, which focused on the basic elements of podcast production. This included capturing time stamps of long pauses, areas where the conversation veered off topic, and noting spots in the interview where a guest or host wanted to correct something they had previously said. Additionally, the SPC looked for any inappropriate language that did not align with the podcast’s efforts to change the language around suicide. For example, having a guest who used the words “committed suicide” re-recorded to say “died by suicide.”

Once the initial review was complete, the SPC sent the recording to the production team at Mental Health News Radio Network (MHNRN), a podcast network company that focuses on mental wellbeing and how it impacts all aspects of life, for the second phase of review. MHNRN listened to the recording, making the actual edits noted by the SPC and providing any feedback from a professional production standpoint. For example, if one of the hosts was speaking too fast or too far away from the microphone, MHNRN would ask the Brain Hijack team to re-record that section. If MHNRN had any questions about the edits sent over by the SPC or if they had any recommendations for further edits, they would schedule a call to discuss with the Brain Hijack team to rework sections of the recording as needed.

After finishing their edits, MHNRN would send the edited episode back to the SPC. The episode would then be sent to the Brain Hijack team’s Center for the Study of Traumatic Stress’ (CSTS) colleagues to begin the third phase of review. This internal review focused on the content of the episode and determined if the language and questions being asked by the hosts and guests aligned with the intent of the podcast while also respectfully representing CSTS’ mission to advance trauma-informed care through education, research, and training. Once the internal review was complete, the episode was submitted to both the Uniformed Services University (USU), which oversees CSTS, and Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine’s (HJF), which oversees CSTS contractors, Public Affairs Offices (PAO) for legal review. The PAO reviewed the episodes for any violations to policies or law that occurred due to the release of an episode that might put USU or HJF at risk. The episode was published to the CSTS Suicide Prevention Program and MHNRN websites and uploaded to Apple, Spotify, and Spreaker platforms after all phases of review were completed. Each episode was made publicly available and promoted through CSTS social media including YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter, press releases, and CSTS distribution emails to colleagues.

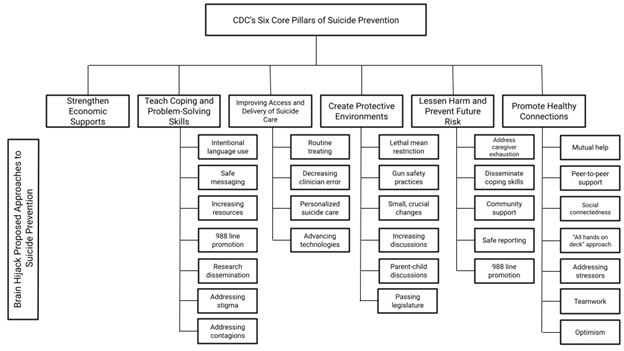

The Brain Hijack team’s anlysis framework consisted of a content analysis of the 6 most robust episodes that best encapsulated the Center for Disease Control’s (CDC) Six Core Pillars of Suicide Prevention model (see Figure 1), dispelling myths, and a holistic approach.

Results

Figure 1 depicts Brain Hijack's use of the Centers for Disease Control’s (CDC) Six Core Pillars of Suicide Prevention model to inform the contents of the podcast. The CDC encourages suicide prevention resources to incorporate six core areas to achieve optimal effectiveness: Strengthen Economic Supports, Teach Coping and Problem-Solving Skills, Improve Access and Delivery of Suicide Care, Create Protective Environments, Lessen Harm and Prevent Future Risk, and Promote Healthy Connections. Out of these areas, Brain Hijack demonstrated the most strength in the areas of Teach Coping and Problem-Solving Skills, Create Protective Environments, and Promote Healthy Connections, by mentioning a wide range of points in these areas. Brain Hijack demonstrated competency but a need for improvement in the areas of Improving Access and Delivery of Suicide Care and Lessening Harm and Preventing Future Risk. Finally, Brain Hijack did not include any points in the area, Strengthen Economic Supports, but plans to address the topic in potential future episodes.

Figure 2 depicts the overall themes of Brain Hijack, categorized as overarching concepts found in all the episodes collectively. Examples of themes related to societal perceptions and involvement include stating common misconceptions, addressing misconceptions with reality checks, or myths, and examining the clinical limitations of suicide prevention. Brain Hijack also addressed themes related to optimism surrounding suicide prevention, such as hope, connectedness, and the value of those who have died by suicide.

Figure 3 depicts Brain Hijack's systematic method of identifying and addressing common societal myths about suicide and suicide prevention. Figure 3 provides episode examples of how myths are first identified and then discussed and dispelled using data and real-life experiences. Myths addressed include: “Asking someone if they are suicidal, makes them more suicidal.” and “Only a mental health professional should ask someone if they have suicidal ideation.” The podcast produced 16 episodes with 2,354 downloads between December 2022 and May 2025, averaging 68 listeners per month. The podcast was accessed mostly through Apple Podcast (43%), the SPP website (23%), and Spotify (19%), with most users listening via their phone (77%).

Figure 4 depicts a Venn diagram of the interconnectedness of three stakeholders in suicide prevention efforts: clinicians, communities, and individuals. Brain Hijack episodes collectively address the need for unity among these stakeholders, while also addressing ongoing contributions and areas of improvement for each individual stakeholder. Overall, the podcast encourages an “all hands on deck” model for suicide prevention due to the interconnectedness of clinicians, the community, and individuals as depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 5 depicts the five-step Brain Hijack naming process. Beginning with brainstorming names, target audiences were then strategically determined, and community members' opinions were collected. Following this, researchers contacted a podcast specialist to narrow down the list of potential names. Lastly, the name, Brain Hijack, was chosen as it reflects what happens when the brain is flooded with radically new information or intense emotions, something the podcast hoped to achieve in its listeners. The name also represents the podcast’s primary focus on mental health.

Discussion

Preventing suicide requires a collective effort and extends far beyond the confines of a mental health provider’s office (see figure 4). To support a culture shift around the topic of suicide prevention, a wider, more diverse audience must be reached, and podcasts are one way to achieve that goal. Emerging public health research on media communication channels indicates that podcasting is a promising tool to reach communities at large or those uniquely at risk. With this understanding, the Suicide Prevention Program (SPP) team at the Center for the Study of Traumatic Stress (CSTS) designed a podcast focused on increasing awareness and a culture shift around suicide prevention while also bridging the gap between science and practice by translating expert recommendations into vernacular understood by scientists as well as non-scientists, military personnel and civilians.

Through a series of interviews and stories, Brain Hijack intends to encourage support-seeking behaviors and connectedness through expert interviews, debunking myths, and normalizing topics in mental health. Using the medium of podcasting, Brain Hijack cultivated conversations that could be understood by all while also building a new listening community for the CSTS.

Each episode, hosts Brooke and Adam met with different experts in suicide prevention to discuss and debunk common misconceptions and myths within the field. The guest expert would provide actionable tools or takeaways for the listeners to use themselves based on the topic of the episode. For example, in Episode Two, “Your Thoughts Do Not Have to be Your Reality, Change is Always Possible,” featuring Dr. Marjan Holloway, showed listeners that they can make a difference in someone’s life who is experiencing suicidal thoughts. Episode two emphasizes that it’s okay to acknowledge and recognize in the moment that you are having suicidal thoughts, and having a suicidal thought does not mean you have to engage in the act of suicide. Listeners leave the episode with practical steps to take when a person is having suicidal thoughts and understanding that one’s thoughts do not have to dictate one’s actions.

While citing progress in the suicide prevention field, Brain Hijack acknowledges certain limitations such as listeners not having the resources they need while listening; however, this is mitigated by a list of helpful resources provided on the CSTS-USU website [13]. The biggest societal limitation is the stigma around openly discussing mental health and an aversion to asking someone if they are considering suicide. In episode eight, Dr. Kelly Posner shares just how impactful having a conversation about mental health is, stating that “Over 90% of incidents where you intervene…they will never go on to try again. People want to be asked. When you do ask, it actually relieves distress.” She discusses clinical limitations, stating that clinicians need to talk to their patients about mental health routinely to find people who may be suffering in silence, citing “50% who die by suicide have seen their caregiver a month before they die.” However, Dr. Posner also discusses the importance of discussing mental health outside of clinical settings, as suicide is a shared crisis of humanity. She encourages everyone, not just doctors or mental health professionals, to not be afraid to reach out to family members or friends who may be struggling and ask hard questions like “Are you thinking of hurting yourself?” as this could make all the difference in that person’s wellbeing. The episode emphasizes how everyone needs to be part of the solution of preventing suicide; communities must start to normalize asking about suicidal ideation and think of it as a value add to their overall wellness.

In episode 7, Dr. Matthew Nock adds to limitation with a reality check, explaining that while predictors for suicide have become better understood, clinicians still have no infallible means of predicting if someone is at risk; however, it does not mean it will not be possible one day.

As part of a public health approach, Brain Hijack will continue to expand its reach and engage diverse audiences in raising awareness about suicide. In doing so, Brain Hijack hopes to contribute to ongoing efforts to normalize suicide prevention in societies across the world. Brain Hijack is just one method, of many needed, for educational institutions to continue leveraging current methods, such as podcasts, to combat suicide and normalize talking about suicide. Podcasts can also inform clinical practice by offering Continuing Education Credits, providing ancillary education to formal classes on clinical practice [14]. It would be curious to research how Brain Hijack could be used to augment a course syllabi on suicide prevention.

The themes and messages of Brain Hijack are timeless and drawn from real-life experiences, making it a valuable tool that can be repurposed. To ensure accessibility for all, Brain Hijack plans to employ accessibility-enhancing tools such as transcripts, high-quality sound, and adjustments of speed text levels, which will improve listener experiences for all audiences. Suicide impacts individuals of all backgrounds, genders, ethnicities, and age groups. Therefore, Brain Hijack is committed to continuing to amplify real-life experiences in each episode. Suicide prevention requires an all hands-on-deck effort from all members of society, and Brain Hijack remains dedicated to doing its part in advancing suicide awareness and encouraging conversation surrounding suicide.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Brooke Heintz Morrissey: Operations Director, Center for the Study of Traumatic Stress

Dr. Adam Walsh: Adjunct Professor, Uniformed Services University in the Department of Medical and Clinical Psychology

Dr. Joshua Morganstein: Deputy Director, Center for the Study of Traumatic Stress

Dr. Keita Franklin: Senior executive, PhD in Social Work from Virginia Commonwealth University

Dr. James West: Associate Professor of Psychiatry and a Scientist at the Center for the Study of Traumatic Stress, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences

Dr. Peter Gutierrez: LivingWorks Executive Vice President, Innovation

Dr. Thomas Joiner: Professor in the Department of Psychology at Florida State University (FSU)

Dr. Kate Comtois: Professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Washington University

Dr. Steven Dubovsky: Professor and Chair of the Department of Psychiatry at the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, State University of New York at Buffalo

Dr. David Jobes: Professor of Psychology, Director of the Suicide Prevention Laboratory, and Associate Director of Clinical Training at The Catholic University of America

Mr. Dennis Ward: Registered Nurse

Dr. Craig Bryan: Board-certified clinical psychologist in cognitive behavioral psychology, Stress, Trauma, and Resilience (STAR), Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Health at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, and is the Division Director for Recovery and Resilience

Dr. Julie Goldstein Grumet: Director of the Zero Suicide Institute at the Education Development Center

Dr. Kelly Posner: Professor of Psychiatry at Columbia University

Dr. Matthew Nock: Professor at Harvard University

Dr. April Naturale: Traumatic Stress Specialist, Interim Executive Director for the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline Cory D. Will, LMSW, QMHP, CPRS: Director of Peer Recovery Services at Rappahannock Rapidan Community Services

Dr. Marjan Holloway: Tenured Professor in the Department of Medical and Clinical Psychology and Psychiatry (MPS) at the

Ms. Miranda Meyer: Senior Program Coordinator, Center for the Study of Traumatic Stress

Ms. Kristen Walker: Cardiovascular Surgeon, First Physicians Group Mental Health News Radio Network

Declaration of Interest Statement

No conflicts were reported by the authors.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Uniformed Services University of the Health Services (Pass-Through Entity: The Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Inc.; PO Number: 1045009, Subaward Number: 5937.

References

World Health Organization. (2025). Suicide. World Health Organization. View

Edison Research and Triton Digital. (2020). The infinite dial 2020. View

Quintana, D. S., & Heathers, J. A. J. (2021). How podcasts can benefit scientific communities. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 25(1), 3–5. View

Casares, D. R. (2022). Embracing the Podcast Era: Trends, Opportunities, & Implications for Counselors. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 17(1), 123–138. View

Shaw, B. R., Sivakumar, G., Balinas, T., Chipman, R., & Krahn, D. (2013). Testing the feasibility of mobile audio-based recovery material as an adjunct to intensive outpatient treatment for veterans with substance abuse disorders. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 31(4), 321–336. View

Shaw, P. A., Sumner, A. L., Halton, C. C., Bailey, S. C., Wolf, M. S., Andrews, E. N., & Cartwright, T. (2022). “You’re more engaged when you’re listening to somebody tell their story”: A qualitative exploration into the mechanisms of the podcast ‘menopause: unmuted’ for communicating health information. Patient Education and Counseling, 105(12), 3494–3500. View

Burns, J. M., Durkin, L. A., & Nicholas, J. (2009). Mental health of young people in the United States: What role can the Internet play in reducing stigma and promoting help seeking? Journal of Adolescent Health, 45(1), 95–97. View

Caoilte, N. Ó., Lambert, S., Murphy, R., & Murphy, G. (2023). Podcasts as a tool for enhancing mental health literacy: An investigation of mental health-related podcasts. Mental Health & Prevention, 30. View

Hanafi, S., Nahiddi, N., Rana, A., Bawks, J., Chen, L., Fage, B., Raben, A., Singhal, N., & Hall, E. (2022). Enhancing psychiatry education through podcasting: Learning from the listener experience. Academic Psychiatry, 46(5), 599–604. View

Alam, F., Boet, S., Piquette, D., Lai, A., Perkes, C. P., & LeBlanc, V. R. (2016, January 1). E-learning optimization: the relative and combined effects of mental practice and modeling on enhanced podcast-based learning—a randomized controlled trial. ADVANCES IN HEALTH SCIENCES EDUCATION, 21(4), 789–802. View

Mailey, E.L., Irwin, B.C., Joyce, J.M. and Hsu, W.-W. (2019), InDependent but not Alone: A Web-Based Intervention to Promote Physical and Mental Health among Military Spouses. Appl Psychol Health Well-Being, 11: 562-583. View

French, P., Hutton, P., Barratt, S., Parker, S., Byrne, R., Shryane, N., & Morrison, A. (2011). Provision of online normalising information to reduce stigma associated with psychosis: Can an audio podcast challenge negative appraisals of psychotic experiences? Psychosis, 3(1), 52–62. View

Resources. CSTS Suicide Prevention Program. (2025). View

Wills, C. D. (2020). Using mental health podcasts for public education. Academic Psychiatry, 44(5), 621–623. View