Journal of Social Work and Welfare Policy Volume 3 (2025), Article ID: JSWWP-149

https://doi.org/10.33790/jswwp1100149Research Article

Predictors of Depression among International Students in a Midwestern University

Eunice A. Yeboah1*, Gyimah Marfo2, April Carter3, Kari-Anne Innes4 and Daniel G. Dieter5

1Department of Psychology, Social Work and Recreational Therapy, Slippery Rock University of Pennsylvania, United States.

2Department of Health Information Systems and Informatics, Slippery Rock University of Pennsylvania, United States.

3Department of Exploratory Studies & Academic Progress (ESAP), Slippery Rock University of Pennsylvania, United States.

4Department of Theatre, Slippery Rock University of Pennsylvania, United States.

5Department of Communication, Media, and Sport Management, Slippery Rock University of Pennsylvania, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Eunice A. Yeboah, MSW, Ph.D., Assistant Professor, Department of Psychology, Social Work and Recreational Therapy, Slippery Rock University of Pennsylvania, United States

Received date: 23rd May, 2025

Accepted date: 19th June, 2025

Published date: 21st June, 2025

Citation: Yeboah, E.A., Marfo, G., Carter, A., Innes, K., & Dieter, D. G., (2025). Predictors of Depression among International Students in a Midwestern University. J Soci Work Welf Policy, 3(1): 149.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Depression is a growing public health concern among international students who often face unique stressors such as cultural displacement, social isolation, financial insecurity, and academic pressure. This study examined predictors of severe depression among international students at Southern Illinois University, focusing on the roles of perceived social support and educational attainment. Logistic regression analysis of 104 survey responses revealed that higher levels of perceived social support significantly reduced the odds of experiencing severe depression by approximately 85 percent (Exp(B) = 0.15). In contrast, each successive level of educational attainment was associated with a threefold increase in depression risk (Exp(B) = 3.08). These findings highlight the urgent need for institutional and policy-level interventions that extend beyond initial orientation programs. Sustained support structures such as peer mentoring, culturally competent counseling, and inclusive campus policies are essential to address the evolving needs of international students, particularly those pursuing advanced degrees. The study calls for integrated, cross-departmental efforts within higher education policy frameworks to promote mental health equity and academic success for this vulnerable population.

Keywords: Mental Health, Social Support Networks, Acculturative Stress, Psychological Well-Being, Higher Education, International Population, Emotional Adjustment

Introduction

The globalization of higher education has led to a rapid rise in the number of students pursuing studies abroad [1]. While living and studying abroad often fosters intellectual growth and broadened perspectives, it also introduces new challenges for students [1]. Cultural adjustment, language barriers, academic expectations, and separation from familiar support systems all combine to create situations that may affect psychological health [2,3].

Prevalence of Depression Among International Students

A robust body of research indicates that international students consistently report higher levels of depressive symptoms compared to their domestic counterparts [4]. Depression frequently emerges as one of the primary concerns among international students who seek assistance from university counseling centers [5,6]. Notably, Yeung et al.[4] documented a significant surge in depression and anxiety among international students in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Tang et al.[7] further demonstrated that lower perceived social support is closely associated with heightened depressive symptoms. Highlighting the extent of unmet mental health needs, Hyun et al. [8] reported that 44% of international graduate students experienced substantial emotional or stress-related difficulties that adversely impacted their well-being and academic performance.

Predictors of Depression

International students are more susceptible to depression because of the range of pressures they encounter. Social, cultural, and demographic characteristics can be used to classify these stressors.

1. Demographic Factors

English language proficiency, age, gender, marital status, ethnicity, and length of stay are important demographic characteristics that affect depression. For instance, the aforementioned were found to be significant predictors of anxiety and sadness by Sümer et al. [14]. Furthermore, it was opined that psychological anguish is more common among students who are female, unmarried, and between the ages of 21 and 30 [36].

2. Social predictors

Social integration obstacles, everyday living difficulties, housing insecurity, financial strain, and a lack of social support have all been identified as key causes of poor mental health among international students [9-11]. Other major social stressors include academic pressure, homesickness, and loneliness [36]. Studies have demonstrated the protective function of social support in reducing stressors and enhancing mental health outcomes [36].

3. Cultural predictors

Acculturation-related problems are a different set of predictors. Students frequently face language obstacles, cultural adjustment issues, and acculturative stress, all of which are associated with depression symptoms [12,13]. Jung et al. [16] discovered that low levels of acculturation and perceived discrimination increase identity conflicts and aggravate sadness. Similarly, Smith and Khawaja [12] discovered that increased acculturative stress is linked to more severe depressive symptoms.

Importantly, acculturation has been found to have a buffering effect, with higher levels of cultural adaption associated with reduced stress and better mental health outcomes [17]. Kristiana et al. [18] underline that cultural dissonance might exacerbate emotions of loneliness, anxiety, and depression.

Social Support as a Protective Factor

A robust body of research underscores the pivotal role of perceived social support as a protective buffer against depression among international students. Family, peer, and institutional networks are consistently cited as essential in alleviating psychological distress, thereby safeguarding against depressive symptoms [19-21]. Chen et al. [22] discovered that passive social media use has a dual effect: it can alleviate feelings of isolation by preserving social relationships, but it can also accidentally worsen loneliness.

The protective influence of social support is particularly salient during cultural adjustment. Yeh and Inose [19] and Misra et al. [20] demonstrated the critical role of social support in promoting psychological well-being in new cultural settings. Building on this, Sümer et al.[14] identified perceived social support alongside gender, age, race, ethnicity, duration of stay, and English proficiency as a significant predictor of mental health outcomes. Tang et al.[7] further expanded the understanding of these dynamics by highlighting additional factors such as academic discipline, nutrition, and self actualization. Digital engagement and discrimination, as noted by Chen et al. [22], also shape psychological outcomes.

While social support plays a vital role in the well-being of international students, the nature of its benefits appears to differ by gender. Male students tend to gain the most from relationships with instructors, whereas female students derive greater benefits from practical assistance, peer relationships, and curriculum flexibility. [21]. However, many international students report challenges in forming meaningful connections with domestic peers. Instead, they often rely on surface-level interactions, which can lead to an increased dependence on faculty members and academic programs as primary sources of support [23,24]. Semester-long classroom experiential activities aimed at promoting interaction between international and domestic students have been shown to enhance international students’ sense of belonging and perceived social support [25].

Collectively, these studies emphasize the multifaceted predictors of depression among international students, with social support emerging as a central protective factor amid a constellation of demographic, cultural, and behavioral influences.

Service Utilization and Institutional Support

Despite experiencing high levels of psychological distress, international students rarely access university counseling services. For example, Hyun et al. [8] discovered that only 17% of international graduate students used campus mental health services, even though a significant proportion reported emotional or stress-related problems and were aware of the availability of such support services, a pattern echoed by Yeung et al.[4] and Dadfar and Friedlander [26]. Several barriers contribute to this underutilization, including stigma and cultural perceptions that frame counseling as untrustworthy or culturally incongruent [26]. Sakız and Jencius [13] further argued that conventional mental health models may conflict with international students’ cultural values, as traditional Western theories may not account for their lived experiences or cultural backgrounds.

To help overcome these challenges, researchers have highlighted the importance of making counseling services more culturally sensitive. For example, Zhang and Dixon [27] emphasized the value of therapy that is responsive to students’ cultural backgrounds and lived experiences. When counseling feels more inclusive and relatable, students may be more likely to view it as helpful and trustworthy. These kinds of changes can go a long way in reducing stigma, making services feel more accessible, and encouraging students to seek the support they need.

Gaps in the Literature and Study Purpose

The psychological, emotional, and physical challenges of migration and college life have sparked increasing scholarly interest in the mental health of international students [2,3]. While existing research has largely focused on the struggles faced by international students in diverse settings, much of this work centers on large urban campuses in the United States [15]. In contrast, students at smaller, regional institutions remain notably underrepresented. These students often encounter heightened isolation, limited cultural resources, and fewer opportunities for meaningful cross-cultural interactions, all of which contribute to their vulnerability [37].

In response to these gaps, the current study explores how perceived social support influences depressive symptoms among international students at a Midwestern university. While previous research has highlighted the importance of family, peer, and institutional support in mitigating mental health challenges, little is known about which specific forms of support are most protective in smaller, regional settings. This study seeks to provide context-specific insights, offering a deeper understanding of the unique pressures faced by international students in these environments.

By examining the environmental and social factors that exacerbate depression among international students, this research aims to inform the development of targeted, culturally sensitive mental health services. Ultimately, the study endeavors to improve strategies for fostering emotional well-being and reducing the stigma of seeking help in smaller university contexts.

Study Design and Setting

This study employed a cross-sectional survey design to examine the relationship between social support and depression among international students enrolled at Southern Illinois University, a Midwestern American university. The target population consisted of international students from diverse academic programs and cultural backgrounds who had resided in the United States for at least six months at the time of data collection.

Participants and Sampling

A purposive sampling strategy was utilized to recruit participants through student organizations, international student services, and the university's international student listserv. Eligible participants were required to be current international students aged 18 years or older. Approximately 1,000 international students were invited to participate in the study via email, and 116 students consented. Of these, 104 participants (42 males and 62 females) completed the entire survey.

Instruments

Data for this study were collected using a structured online questionnaire administered through SurveyMonkey. The instrument comprised four main sections, each targeting key variables relevant to the study objectives:

Demographic Information: Participants provided basic demographic details, including age, gender, length of stay in the United States, and country of origin. These variables were used to assess group differences and potential predictors of mental health outcomes.

Social Support Measures: Perceived social support was assessed using two well-validated instruments:

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS): This 12-item scale evaluates perceived emotional and instrumental support from three sources—family, friends, and significant others. Each item is rated on a 7-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater perceived support [28].

Social Provisions Scale (SPS): A 24-item instrument designed to measure the extent to which social relationships provide various forms of support, such as attachment, guidance, and opportunities for nurturance. The SPS captures the functional dimensions of social support, extending beyond emotional perception to practical provisions [29].

Depression Measures: To assess the presence and severity of depressive symptoms, the following standardized tools were utilized:

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9): A widely used 9-item self-report scale measuring the frequency of depressive symptoms over the past two weeks. Scores range from 0 to 27, with established cutoffs indicating mild to severe depression [30].

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS): This 14-item instrument includes two subscales—HADS-D (depression) and HADS-A (anxiety)—each with seven items. Designed to minimize confounding from somatic symptoms, the HADS focuses on cognitive and emotional indicators, making it suitable for diverse populations, including international students [31].

Alternative Depression Measure

Berk's Depression Inventory: This 21-item self-report instrument assesses a range of depressive attitudes and symptoms [32]. It was included to cross-validate depressive symptomatology and offer an alternative framework for identifying psychological distress among participants.

Procedure

Following approval from the Southern Illinois University Institutional Review Board (IRB), an invitation letter describing the study was distributed via email to all international students. The letter included a link to the online survey hosted on SurveyMonkey, an informed consent form, and a statement of voluntary participation, emphasizing the right to withdraw at any time. Only participants who provided electronic consent could proceed with the survey. To maintain anonymity, no identifying information was collected.

Data Analysis

Logistic regression was performed to determine the predictive value of social support variables on depression outcomes. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS version 26, with statistical significance set at p < 0.05.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Southern Illinois University Institutional Review Board (Protocol Number: 19189). All participants provided electronic informed consent before participation. Confidentiality and anonymity were maintained throughout the study. Data were securely stored and accessed only by the research team for research purposes.

Results and Discussions

Participants Demographics

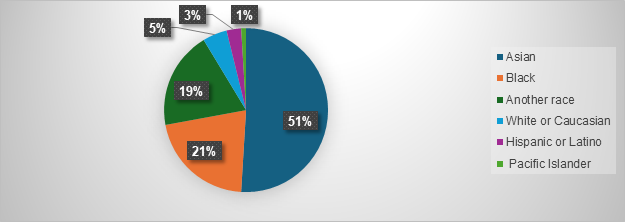

Race: The racial distribution of the international student sample revealed that a majority identified as Asian (50.96%). Other racial groups included Black (21.15%), Other (19.23%), White or Caucasian (4.81%), Hispanic or Latino (2.88%), and Pacific Islander (0.96%). This distribution underscores the predominance of Asian representation among the surveyed participants, as illustrated in Figure 1

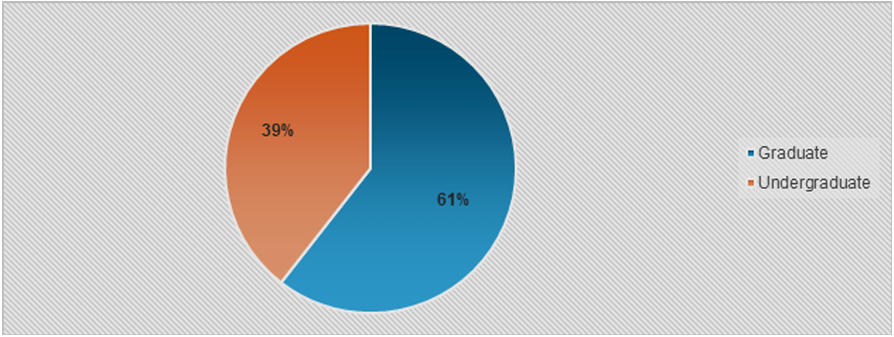

Education: 60.58% of respondents reported graduate-level education, compared to 39.42% who reported undergraduate-level education, as seen in Figure 2. These numbers indicate that the majority of the sample is enrolled in or has earned advanced degrees.

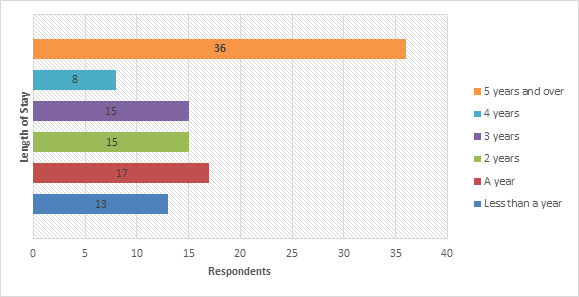

Figure 3 illustrates the distribution of the length of time international students have resided in the United States. Participants reported varied durations of residence in the U.S.: 34.62% (36 respondents) had been in the country for five years or more; 16.35% (17 respondents) for one year; 14.42% (15 respondents) for two years; 14.42% (15 respondents) for three years; 12.50% (13 respondents) for less than one year; and 7.69% (8 respondents) for four years. The data indicate a substantial segment of long-term residents within the international student population.

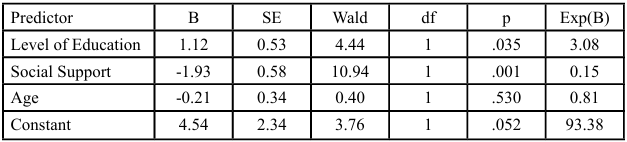

A logistic regression analysis was conducted to evaluate the influence of social support, educational level, and age on the likelihood of severe depression among international students.

Key findings include:

• Level of Education: Positively associated with depression (B = 1.12, SE = 0.53, Wald = 4.44, p = .035), with an odds ratio (OR) of 3.08,

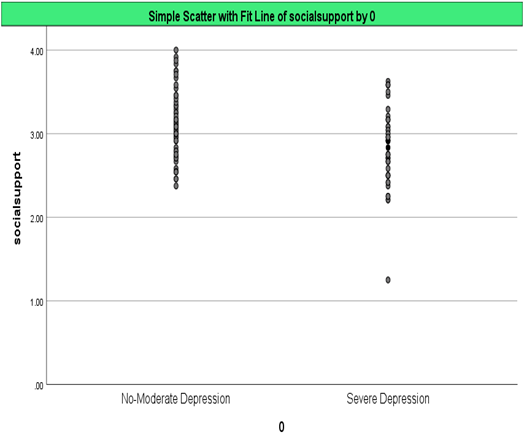

Figure 4: Scatterplot depicting the inverse relationship between social support, no-moderate depression, and severe depression levels

Figure 4 displays a scatter plot illustrating the relationship between depression severity and perceived social support. Individuals with severe depression generally reported slightly lower social support scores than those with no to moderate depression. Most ratings were clustered between 3.0 and 4.0 in both groups, although a few outliers were observed in the severe depression group.

• Social Support: Inversely associated with depression (B = -1.93, SE = 0.58, Wald = 10.94, p = .001), OR = 0.15.

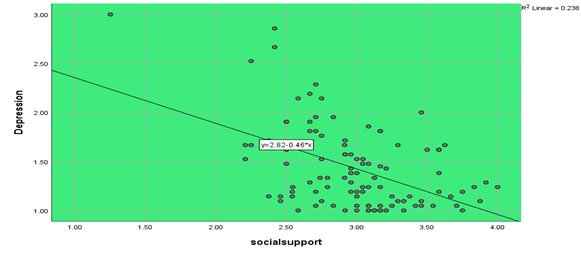

Figure 5: Scatterplot depicting the inverse relationship between social support and depression levels

Figure 5 presents a scatter plot illustrating the linear relationship between perceived social support and depression levels. The regression analysis produced a negative slope (y = 2.82 − 0.46x), indicating an inverse association between the two variables. Specifically, higher levels of perceived social support are associated with lower depression scores.

The coefficient of determination (R² = 0.238) indicates that approximately 23.8% of the variance in depression scores is accounted for by differences in perceived social support. While the data points exhibit some dispersion around the regression line, the overall trend suggests a moderate but meaningful association.

• Age: Not a significant predictor (p = .530).

• The overall model was statistically significant, χ²(3) = 20.57, p < .001, accounting for approximately 24% of the variance in depression status (Nagelkerke R²).

Discussion

The logistic regression model identified key predictors of severe depression among international students. Both perceived social support and educational attainment emerged as statistically significant factors. Specifically, each incremental increase in education level was associated with a threefold increase in the odds of experiencing severe depression (Exp(B) = 3.08). In contrast, higher levels of perceived social support significantly reduced the likelihood of severe depression by approximately 85% (Exp(B) = 0.15), after controlling for other variables. Notably, age did not significantly predict depression risk within this model.

These findings support the study’s primary hypothesis that social support serves as a significant protective factor against depression in this population. The inverse relationship between social support and depression was robust, with each unit increase in support corresponding to a substantial decrease in the likelihood of severe depressive symptoms. Conversely, increased educational attainment was associated with elevated risk, suggesting that students pursuing advanced degrees may face heightened vulnerability.

The association between higher academic levels and increased depression risk likely reflects compounding stressors such as intensified academic demands, financial burdens, and extended separation from familial and cultural support systems. This aligns with the concept of spiritual homelessness [33], which describes the emotional and cultural displacement often experienced by international students. While many institutions focus support efforts on early-stage integration through orientation and retention programs, these findings underscore the importance of sustained and adaptive support mechanisms throughout students’ academic trajectories. Targeted interventions that address the evolving psychosocial needs of upper-level and graduate international students are critical to mitigating depression risk and fostering long-term well-being.

Implications and Recommendations

The findings carry significant implications for institutional policy and mental health support. Enhancing perceived social support through targeted interventions such as peer mentoring, culturally sensitive counseling, and inclusive social programming can mitigate depression risk. Support services must evolve to address the complex needs of upper-level students.

Furthermore, mental health interventions should be tailored to academic disciplines. Previous research by Tang et al. [7] has shown elevated depression rates among medical students (40.1%) compared to those in science and engineering (23.3%) and the arts (25.3%). Discipline-specific approaches may enhance intervention efficacy.

Broader Context and Public Health Relevance

The increased prevalence of depression among college students, particularly post-COVID-19, places international students at heightened risk due to additional stressors such as cultural adjustment and family separation [4,34,35]. These findings underscore the urgency for universities to implement comprehensive, culturally competent strategies that promote social integration and mental well being.

Cross-campus collaborations spanning health services, student affairs, financial aid, and cultural organizations can bolster international students’ support networks and facilitate mental health resilience.

Limitations

One significant weakness of this study is its reliance on an online survey, mostly completed via mobile devices, which may have reduced response depth. Furthermore, given the sample's multinational nature, language hurdles and probable question misinterpretation could have contributed to dataset outliers.

Sampling Constraints: A limited data collection window, influenced by academic scheduling and institutional deadlines, may have affected recruitment and participation rates.

Generalizability: The study's single-institution scope limits its broader applicability. Future research should incorporate extended timelines and diverse institutional contexts to enhance representativeness and external validity.

Concluding Remarks

This study provides valuable insights that can inform university policies and programming. Strengthening social support systems for international students has the potential to reduce depression significantly. The findings emphasize that such support should be dynamic, adapting to students’ evolving needs throughout their academic journeys. Future research should continue to explore nuanced factors such as academic discipline, length of stay, and cultural integration that shape the mental health of international students. By doing so, institutions can better equip themselves to create inclusive environments where all students can thrive.

Competing Interests:

The authors declared that there were no conflicts of interest related to the content of this manuscript.

References

Shaikh, F. (2024). Exploring challenges faced by international college students: A comprehensive study. AMITESH Publisher & Company. View

Chen, J. H., Li, Y., Wu, A. M. S., & Tong, K. K. (2020). The overlooked minority: Mental health of international students worldwide under the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 54, 102333. View

Dovchin, S. (2020). The psychological damages of linguistic racism and international students in Australia. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 23(7), 804 818. View

Yeung, T. S., Hyun, S., Zhang, E., Wong, F., Stevens, C., Liu, C. H., & Chen, J. A. (2022). Prevalence and correlates of mental health symptoms and disorders among US international college students. Journal of American College Health, 70(8), 2470 2475.View

Saravanan, C., & Subhashini, G. (2021). A systematic review on the prevalence of depression and its associated factors among international university students. Journal of Mental Health and Human Behaviour, 17(1), 13–25. View

Hwang, B. J., Bennett, R., & Beauchemin, J. (2014). International students' utilization of counseling services. College Student Journal, 48(3), 347–354.View

Tang, Z., Feng, S., & Lin, J. (2021). Depression and its correlation with social support and health-promoting lifestyles among Chinese university students: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 11(7), e044236.View

Hyun, J., Quinn, B., Madon, T., & Lustig, S. (2007). Mental health need, awareness, and use of counseling services among international graduate students. Journal of American College Health, 56(2), 109–118. View

Atri, A., Sharma, M., & Cottrell, R. (2007). Role of Social Support, Hardiness, and Acculturation as Predictors of Mental Health among International Students of Asian Indian Origin. International Quarterly of Community Health Education. 27(1):59-73. View

Shek, C. H. M., Chan, S. W. C., Stubbs, M. A., & Lee, R. L. T. (2024). Promoting international students’ mental health unmet needs: An integrative review. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 26(11), 905–924. View

Shadowen, N. L., Williamson, A. A., Guerra, N. G., Ammigan, R., & Drexler, M. L. (2019). Prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms among international students: Implications for university support offices. Journal of International Students, 9(1), 129–148. View

Smith, R. A., & Khawaja, N. G. (2011). A review of the acculturation experiences of international students. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35(6), 699–713. View

Sakız, H., & Jencius, M. (2024). Inclusive mental health support for international students: Unveiling delivery components in higher education. Global Mental Health, 11, e8. View

Sümer, S., Poyrazli, S., & Grahame, K. (2008). Predictors of depression and anxiety among international students. Journal of Counseling & Development, 86(4), 429–437. View

Oduwaye, O., Kiraz, A., & Sorakin, Y. (2023). A trend analysis of the challenges of international students over 21 years. SAGE Open, 13(4). View

Jung, E., Hecht, M. L., & Wadsworth, B. C. (2007). The role of identity in international students’ psychological well-being in the United States: A model of depression level, identity gaps, discrimination, and acculturation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 31(5), 605–624. View

Salerno, K. C., Tuason, M. T., Stanton, B., & Buchanan, S. (2024). What makes an international student in the U.S. have less psychological distress? SAGE Open, 14(3). View

Kristiana, I. F., Karyanta, N. A., Simanjuntak, E., Prihatsanti, U., Ingarianti, T. M., & Shohib, M. (2022). Social support and acculturative stress of international students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(11), 6568. View

Yeh, C. J., & Inose, M. (2003). International students' reported English fluency, social support satisfaction, and social connectedness as predictors of acculturative stress. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 16(1), 15–28. View

Misra, R., Crist, M., & Burant, C. J. (2003). Relationships among life stress, social support, academic stressors, and reactions to stressors of international students in the United States. International Journal of Stress Management, 10(2), 137–157. View

Mallinckrodt, B., & Leong, F. T. (1992). International graduate students, stress, and social support. Journal of College Student Development, 33(1), 71–78. View

Chen, Y. A., Fan, T., Toma, C. L., & Scherr, S. (2022). International students’ psychosocial well-being and social media use at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic: A latent profile analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 137, 107409. View

Bulthuis, J. D. (1986). The foreign student today: A profile. New Directions for Student Services, 1986(36), 39–48. View

Heikinheimo, P. S., & Shute, J. C. (1986). The adaptation of foreign students: Student views and institutional implications. Journal of College Student Personnel, 27(5), 399–406 View

Caligiuri, P., DuBois, C. L. Z., Lundby, K., & Sinclair, E. A. (2020). Fostering international students’ sense of belonging and perceived social support through a semester-long experiential activity. Research in Comparative and International Education, 15(4), 357-370. View

Dadfar, S., & Friedlander, M. L. (1982). Differential attitudes of international students toward seeking professional psychological help. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 29(3), 335–338. View

Zhang, N., & Dixon, D. N. (2001). Multiculturally responsive counseling: Effects on Asian students' ratings of counselors. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 29(4), 253–262. View

Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 30–41. View

Cutrona, C. E., & Russell, D. W. (1987). Social Provisions Scale [Database record]. APA PsycTests. View

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (1999). Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) [Database record]. APA PsycTests. View

Michopoulos, I., Douzenis, A., Kalkavoura, C., Christodoulou, C., Michalopoulou, P., Kalemi, G., Fineti, K., Patapis, P., Protopapas, K., & Lykouras, L. (2008). Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS): validation in a Greek general hospital sample. Annals of general psychiatry, 7, 4. View

/li>Beck, A.T., Ward, C. H., Mendelson, M., Mock, J., & Erbaugh, J. (1961). An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 4, 561-571. View

Maleku, A., Phillips, R., Um, M. Y., Kagotho, N., Lee, G., & Coxe, K. (2021). The phenomenon of spiritual homelessness in transnational spaces among international students in the United States. Population, Space and Place, 27(6), e2470. View

Fruehwirth, J. C., Biswas, S., & Perreira, K. M. (2021). The COVID-19 pandemic and mental health of first-year college students: Examining the effect of COVID-19 stressors using longitudinal data. PLOS ONE, 16(3), e0247999. View

Kivela, L., Mouthaan, J., van der Does, W., & Antypa, N. (2022). Student mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: Are international students more affected? Journal of American College Health. View

Rahman, M. A., & Kohli, T. (2024). Mental health analysis of international students using machine learning techniques. PLOS ONE, 19(6), e0304132. View

Olt, P. A., & Tao, B. (2020). International students’ transition to a rural state comprehensive university. Teacher-Scholar: The Journal of the State Comprehensive University, 9(1), Article 4. View