Journal of Social Work and Welfare Policy Volume 3 (2025), Article ID: JSWWP-150

https://doi.org/10.33790/jswwp1100150Research Article

Fantasy Expressive Arts Therapy in Family Caregiver Support Programs: A Narrative and Interpretative Phenomenological Approach

Hui Ching Cheng1*, & Ming Ju Wu2

1PhD Candidate, Department and Institute of Social Welfare, National Chung Cheng University, No. 168, Sec. 1, University Rd., Minhsiung, Chiayi 621301, Taiwan.

1Research Assistant, Institute of Population Health Sciences, National Health Research Institutes (NHRI), No. 35, Keyan Road, Zhunan Town, Miaoli County 350401, Taiwan, ROC.

2Professor, Department and Institute of Social Welfare, National Chung Cheng University, No. 168, Sec. 1, University Rd., Minhsiung, Chiayi 621301, Taiwan.

Corresponding Author Details: Hui Ching Cheng, PhD Candidate, Department and Institute of Social Welfare, National Chung Cheng University, No. 168, Sec. 1, University Rd., Minhsiung, Chiayi 621301, Taiwan.

Received date: 08th May, 2025

Accepted date: 20th June, 2025

Published date: 22nd June, 2025

Citation: Cheng, H. C., & Wu, M. J., (2025). Fantasy Expressive Arts Therapy in Family Caregiver Support Programs: A Narrative and Interpretative Phenomenological Approach. J Soci Work Welf Policy, 3(1): 150.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

This study investigates the application and effectiveness of Fantasy Expressive Arts Therapy within a community-based family caregiver support program for caregivers supporting individuals with disabilities, and elders with functional impairments. Employing Narrative Inquiry and Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA), the facilitator guided participants through six 90-minute group sessions, using picture books, mandalas, horticultural activities, visual cards, and tangle art. Data sources included session transcripts and participants’ creative artifacts. Results indicated that participants experienced emotional release, reconnection through shared experience, and reconstruction of caregiving identity. Self efficacy scores significantly increased post-intervention (p < .05), accompanied by more supportive family interactions and positive caregiving attitudes. Findings confirm that Fantasy Expressive Arts Therapy is an effective community intervention to enhance caregiver resilience and mutual support networks, with implications for practice and policy.

Keywords: Fantasy Expressive Arts Therapy; Family Caregivers; Narrative Inquiry; Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis; Community Support

Introduction

Background and Rationale

As Taiwan’s population ages and the number of persons with disabilities rises, family caregivers face increasing psychosocial burdens. Government initiatives such as respite services, caregiving skills workshops, and stress-relief groups have been introduced. Traditional verbal interventions alone may not adequately address caregivers’ emotional needs. Fantasy Expressive Arts Therapy integrates Jungian symbolism with multimodal creative media to facilitate nonverbal emotional expression and self-exploration [1,2].

Fantasy Expressive Arts Therapy: Symbolic and Integrative Model

Fantasy Expressive Arts Therapy is an integrative healing approach combining fantasy, symbolism, and artistic expression. Unlike traditional art therapy, it posits that each individual harbors a unique inner world ("the vision of the world with imagination"). Through personalized imaginative journeys and creative expression, participants shape narratives that reflect their inner cultural meanings and lived experiences. This model emphasizes bringing repressed unconscious content into consciousness and facilitating interpretation and self-healing through artistic media [1,3].

Integrative Theoretical Foundations

The theoretical basis of Fantasy Expressive Arts Therapy integrates multiple psychological and art therapy traditions:

1. Jungian Psychology: Emphasizes the importance of the unconscious, symbols, and archetypes. Artistic creation serves as a tangible manifestation of unconscious content, allowing caregivers to explore inner sources of stress and achieve self integration and healing [4].

2. Expressive Arts Therapy (EXA): Developed by Knill, McNiff, and colleagues, it holds that multimodal art media foster deep emotional expression and internal exploration [5].

3. Humanistic Psychology: Rogers’ person-centered therapy emphasizes unconditional positive regard, empathy, and genuineness. Expressive Arts Therapy provides a nonjudgmental creative space that promotes self-exploration and self acceptance [6].

Caregiver Burden and Group Therapy Foundations

Family caregivers endure multifaceted stress from physical, psychological, and social demands. Taiwan entered an aging society in 2018; as the population ages, the demand for care increases, imposing substantial caregiving burdens [7]. Common stressors include helplessness toward illness, inadequate medical resources, financial pressure, weak family support, and the singularization of caregiving responsibilities [8]. Without effective support, caregivers may experience anxiety, depression, burnout, and collapse [9]. Caregiver support groups—through mutual sharing, experience exchange, and emotional support—have effectively reduced caregivers’psychological burden [10].

Marmarosh et al., [11] identifies core group therapy factors as mutual support, emotional expression, and existential exploration. In expressive arts support groups, caregivers use creative media to safely articulate unspeakable pain and build supportive connections. Additionally, this approach reconstructs self-narrative—shifting caregivers from “powerless” to “empowered participants,” a transformative process foundational to long-term support and psychological resilience [1]. Marmarosh et al.’s therapeutic factors— emotional expression, interpersonal learning, role modeling, and group cohesion—are realized in these groups, enhancing emotional release, social support, and coping capacity [11]. Caregivers often experience emotional exhaustion, social isolation, and financial pressure, leading to anxiety, depression, and burnout [9]. Group therapy factors—mutual support, emotional expression, and meaning-making—are central to healing [11]. Combining these with creative arts media offers a safe space for caregivers to articulate unspoken emotions and build supportive networks.

Compared to traditional verbal caregiving support programs, our study uniquely demonstrates how symbolic and nonverbal artistic methods significantly deepen emotional expression and self-identity reconstruction, providing a richer therapeutic avenue.

Methods

Research Design and Participants

This qualitative study employed a combined Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) and Narrative Inquiry design to gain an in-depth understanding of family caregivers’ subjective experiences and meaning-making processes within the Fantasy Expressive Arts Therapy support program. Seven primary family caregivers of disabled or functionally impaired elders (35–70 years old; 80% female) were purposively invited. All participants volunteered and provided written informed consent for the collection of: (1) audio-recorded session transcripts, (2) participants’ creative artifacts, and (3) in-depth interviews.

Intervention Procedures

Participants attended weekly group sessions over six weeks, each lasting 90 minutes. Sessions were structured to include:

• Creative Arts Activities: Using picture books, mandalas, horticulture, visual cards, and tangle art to facilitate expression.

• Thematic Exploration: Guided discussions on caregiving experiences and emotional themes.

• Group Sharing: Collective reflection and mutual support exercises.

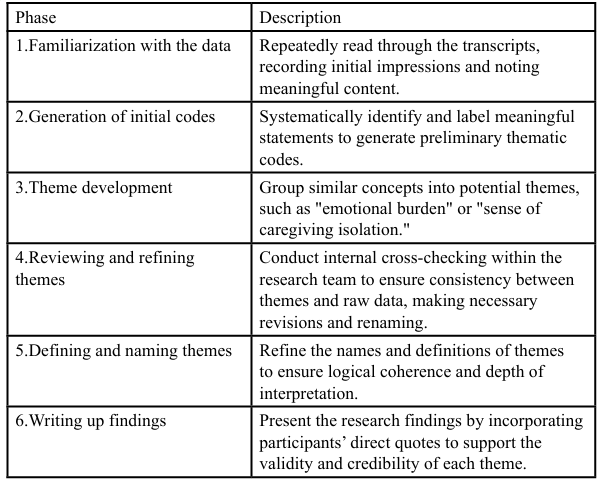

Coding Procedure

This study adopts Braun and Clarke’s thematic analysis method and follows their six-phase approach to qualitative data analysis (Table 1): familiarization with the data, generation of initial codes, development of themes, reviewing and refining themes, defining and naming themes, and writing up the findings.

Data Collection and Analysis

The data sources included transcripts of group sessions, participants’creative works, and follow-up interviews. IPA followed the steps of Smith et al. [12]— repeated reading, preliminary theme generation, thematic network construction, and meaning unit interpretation. Narrative analysis adhered to Cole et al. [13], focusing on story progression, emotional shifts, and meaning construction.

Validation Methods

To enhance the credibility and validity of the study, four strategies recommended by Lincoln and Guba [14]] were employed: triangulation (including group meeting records, participants’creative works, and follow-up interviews), member checking, peer debriefing, and audit trail.

The researcher, who served as both the designer and facilitator of the group, brought valuable practical experience and empathetic understanding to the research. Nevertheless, this dual role also introduced the risk of interpretative bias, which was mitigated through regular peer debriefing and reflective memo-writing.

Results

Case Transformations and Thematic Interpretation

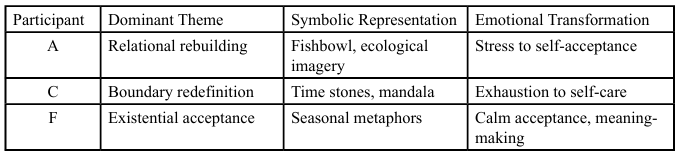

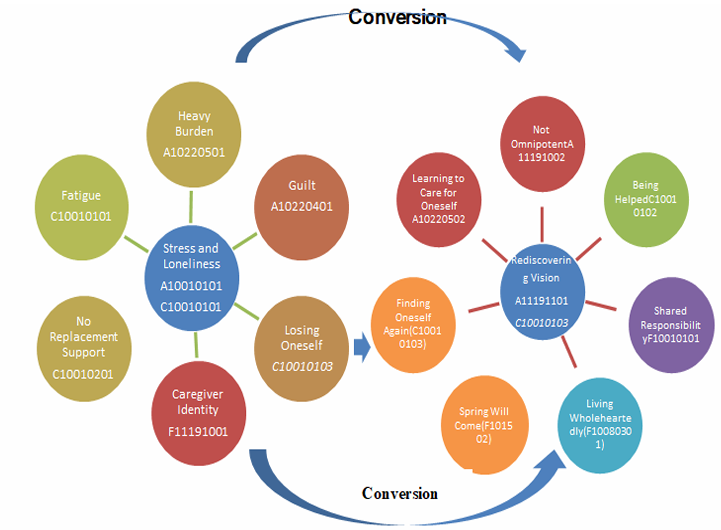

Data analysis followed the IPA steps of Smith et al. [12]— repeated reading, preliminary theme generation, thematic network construction, and meaning unit interpretation—and narrative analysis per Cole et al. [13], centering on story progression, emotional shifts, and meaning construction. Three participants (pseudonyms A, C, and F) were selected as exemplar cases to illustrate inner transformation and interpretive themes:

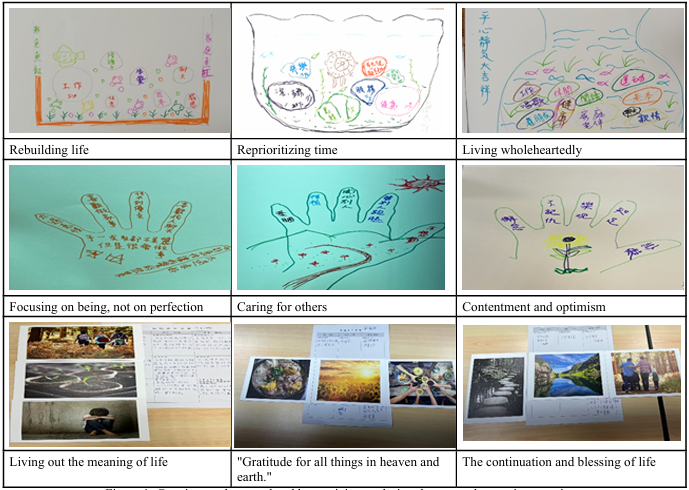

Participant A (female, 60, primary caregiver for her daughter and husband) initially spoke in a heavy tone about caregiving stress and loneliness, frequently using terms such as “guilty,” “tired,” and “can’t go on.” Through successive art-making and group sharing, her language shifted toward self-affirmation and emotional release: “I used to feel like I did everything wrong, but here…I cried and laughed, and felt so much lighter.” (A10010103) In her final fishbowl artwork, she added sunlight, aquatic plants, and stones to symbolize “rebuilding life.” She reflected, “I feel I can slowly accept that I’m not an all-capable caregiver, and it’s okay to cry.” (A11191002)

Figure 2. Participant A’s final fishbowl artwork illustrating emotional transformation from caregiving stress to self-acceptance and reconstruction of life meaning.

Participant C (female, retired caregiver) entered the group in a state of self-exhaustion after caring for her ill brother and husband. She created imagery representing “reordering,” and stated, “I’ve always been the helper, but this time, I finally let myself be helped.” (C10010102) Her mandala, composed of overlapping circles, symbolized reconstructed boundaries between self and others: “This marks my starting point to find myself again.” In a “time stones” project, she depicted life allocation in a glass jar and realized, “I only reserved 5% of my time for myself—I gradually lost myself in caregiving.” (C10010103) This revelation prompted her to assert in the final session, “I need to relearn how to care for myself.”

Figure 3. Participant C’s Through the fishbowl artwork, the participant discovered that only 5% of their time was reserved for themselves, as symbolized by the time stone. The overlapping circles in the mandala further revealed their deep-seated desire to be helped and cared for.

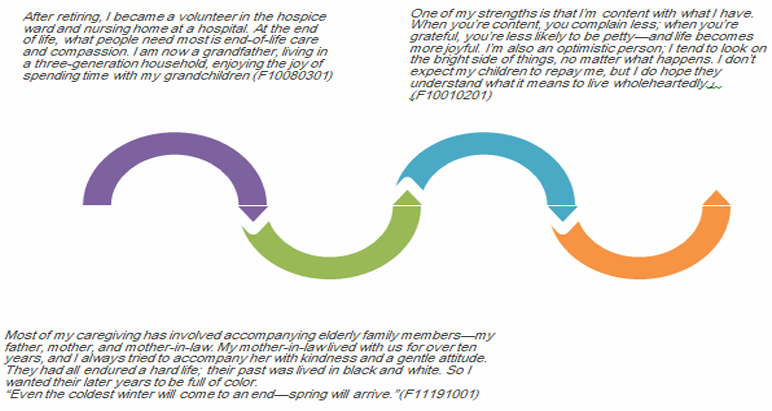

Participant F (male, retired caregiver) shared calmly and with acceptance of aging, framing caregiving as “life’s lesson.” He often encouraged peers poetically: “Life is like four seasons—there is withering and flourishing. The key is to appreciate the present scenery.” His mandala titled “Seasonal Transitions” depicted caregiving as cyclical seasons; he remarked, “Even the coldest winter will end, and spring will come.” (F11191001) In a sand tray exercise, he planted a sapling to symbolize life continuation and blessing. Through picture book narration, he revisited three generations of family caregiving: “I don’t seek repayment from my children, but I want them to know what it means to ‘live wholeheartedly.’” (F10080301)

Figure 4. Participant F’s Through the mandala, the participant perceived the cyclical nature of life, symbolizing both its continuation and transformation, with the hope that the next generation can “live wholeheartedly.

Cross-Case Thematic Comparison

Although each participant’s story was emotionally rich and vividly detailed, a cross-case thematic comparison reveals both commonalities and differences in the transformation of caregiving roles. For example, both Participant A and Participant C demonstrated a process of moving from stress and exhaustion to self-reconstruction. However, A expressed this transformation through relational imagery (such as fishbowls and ecological motifs), while C used boundary- related symbols (such as time stones and mandalas) to depict the redefinition of self and others.

In contrast, Participant F adopted a more philosophical approach to the caregiving process, incorporating metaphors of seasonal cycles to represent the continuity of life. His narrative exhibited less emotional turbulence and more existential acceptance and meaning-making, reflecting an intergenerational caregiving ethic.

This comparison suggests that different life stages and caregiving contexts influence the choice of symbolic representations and narrative expressions, highlighting the adaptability and depth of Fantasy Expressive Arts Therapy across diverse caregiver experiences.

Emotional Release and Healing Process

Throughout the group journey, creative activities and narrative sharing served as vital conduits for releasing suppressed emotions. Members moved from initial silence and inhibition to expressing grief and guilt through color in drawings, symbolic arrangements in sand trays, and storytelling. For example, one elder caregiver, upon completing a fishbowl creation reflecting both gratitude and sorrow, wept as she said: “I always thought I couldn’t show emotion, but this time I finally let my tears flow,” symbolizing the heavy burden and loneliness she carried. Another participant used tangle art to depict emotional entanglement, receiving empathetic reflections that deepened her sense of being understood. These artistic processes allowed for safe emotional flow and marked a turning point in psychological healing.

Awareness of Support Systems and Attachment

Group interactions fostered a newfound recognition of supportive relationships. By hearing about similar experiences, participants aroused the sentiment, "I am not alone," which generated emotional identification and motivated them to seek help externally. One member reflected, “We caregivers always put ourselves last; today someone asked me: ‘And you? How are you?’” This peer mirroring rebuilt a sense of security. Participants reported forming new attachment bonds within the group and, subsequently, a willingness to reach out to family, friends, and community resources. As one caregiver noted, “I thought only I experienced this pain—now I realize we all struggle.” This realization shifted caregiving from an isolated endeavor to a shared responsibility: “Caring isn’t something I must bear alone—others can help too.”

Reconstruction of Future Vision and Hope

In the final sessions, most participants began to envision renewed futures, using symbolic motifs such as the sun, seeds, and aquariums to express hope and intention for self-care. Activities like planting sprouts, crafting aquarium installations, and writing “letters to my future self” represented commitments to personal growth and well-being. One caregiver wrote: “I learned it’s not just about caring for others—I need to care for myself, too.” Artworks depicting sunlight and growth conveyed emerging hope: “After the darkest times, I can see light again,” illustrating a restored sense of purpose and forward-looking agency.

Participants used symbols—sun, seeds, aquariums—to express renewed life goals and commitment to self-care, demonstrating increased hope and action orientation.

Discussion

Theoretical and Practical Implications

The integration of narrative inquiry and creative arts therapy effectively enhanced self-efficacy, emotional expression, and social support, consistent with prior literature [10,11]. Fantasy Expressive Arts Therapy offers a nonverbal modality to address caregiver needs. According to the expressive arts theory developed by Knill and McNiff [5], multimodal art media can stimulate individuals' inner creative potential, transform emotional tension into expressive energy, and generate healing effects [15]. The creative processes and emotional transformations observed in this study—such as the symbolic meanings found in fishbowl and mandala artworks— clearly support this view.

Recommendations for Practice and Policy

Community caregiver support programs should incorporate Fantasy Expressive Arts Therapy and digital platforms to expand reach. Policymakers should allocate resources for facilitator training and program funding. Policymakers are encouraged to promote the diffusion and localization of innovative caregiving intervention models, such as implementing this approach in long-term care community hubs (C-points), community colleges, or day care centers to improve accessibility.

Limitations and Future Research

Limitations include small sample size and lack of quantitative control group. Future studies should employ quasi-experimental designs, larger samples, long-term follow-up, and explore diverse cultural contexts. It is also recommended to explore the participation experiences and cultural appropriateness of expressive arts therapy among diverse populations, such as male caregivers, immigrants, and Indigenous communities.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Conclusion and Practical Implications

This study confirmed that combining creative artistic practice with narrative processes enables caregivers to construct meaning, experience healing in a safe space, and enhance psychological resilience. Through six weeks of Fantasy Expressive Arts Therapy integrated with a family caregiver support group, participants demonstrated significant improvements in self-efficacy, emotional expression, interpersonal support, and sense of life meaning. Narrative and interpretative phenomenological analyses illustrated a transition from feeling 'imprisoned' to experiencing 'awareness and transformation,” in which caregivers reconstructed the meaning of caregiving and self-worth within a safe, accepting, and creative group atmosphere.

Future Research Directions

Fantasy Expressive Arts Therapy offers a creative, safe, and transformative support pathway for caregivers, addressing the psychological health needs of aging and caregiving populations with high practical value. Future studies should consider expand sample sizes, adopt quasi-experimental designs with long-term follow-up to verify sustained benefits on caregivers’ mental and physical health, and deepen exploration of psychological needs and intervention experiences across different disabilities, genders, and cultural contexts. Developing localized, culturally sensitive support strategies and integrating digital tools—such as online support platforms and digital art creation—can overcome geographic and temporal barriers, enabling more caregivers to benefit.

Future research should explore how Fantasy Expressive Arts Therapy can be culturally adapted to caregivers in other international contexts, broadening the global applicability of this therapeutic approach.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Institute of Population Health Sciences, National Health Research Institutes (NHRI), Taiwan, under the grant numbers NHRI-PH-113-GP-17 and NHRI-PH-114-GP-05.

Competing Interests:

The authors of this research declare no competing interest regarding this study.

References

Abdul Rahman, S. N. H., Mahmud, M. I., & Ku Johari, K. S. K. (2024). Exploring of expressive art therapy in counselling: A recent systematic review. Qubahan Academic Journal, 4(2), 430–457. View

Joschko, R., Klatte, C., Grabowska, W. A., Roll, S., Berghöfer, A., & Willich, S. N. (2024). Active visual art therapy and health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Network Open, 7(9), e2428709. View

Chen, Y.-C., Chang, T.-C., & Yang, H.-M. (2015). Interpretation and self-healing in the artistic creation process: An art therapy perspective. Art Studies, 18, 57–86.

Goodwyn, E. (2022). Archetypes and clinical application: How the genome responds to experience. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 67, 838–859. View

Phillips, C. S., Hebdon, M., Cleary, C., Ravandi, D., Pottepalli, V., Siddiqi, Z., Rodriguez, E., & Jones, B. L. (2024). Expressive arts interventions to improve psychosocial well-being in caregivers: A systematic review. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 67(3), e229–e249. View

Burgers, J. S., van der Weijden, T., & Bischoff, E. W. M. A. (2021). Challenges of research on person-centered care in general practice: A scoping review. Frontiers in Medicine, 8, 669491. View

Ministry of the Interior (Taiwan). (2018). White paper on the aging society in Taiwan. Taipei: Ministry of the Interior. View

Hsu, S.-M. (2013). Caregiving experiences and support needs of female primary caregivers (Master’s thesis). National Sun Yat sen University.

González-Fraile, E., Ballesteros, J., Rueda, J.-R., Santos Zorrozúa, B., Solà, I., & McCleery, J. (2021). Remotely delivered information, training and support for informal caregivers of people with dementia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 1, CD006440. View

Zhai, S., Chu, F., Tan, M., Chi, N.-C., Ward, T., & Yuwen, W. (2023). Digital health interventions to support family caregivers: An updated systematic review. Digital Health, 9. View

Marmarosh, C. L., Sandage, S., Wade, N., Captari, L. E., & Crabtree, S. (2022). New horizons in group psychotherapy research and practice from third wave positive psychology: A practice-friendly review. Research in Psychotherapy: Psychopathology, Process and Outcome, 25(3), 258–270. View

Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method and research. London: SAGE Publications. View

Cole, A., Kemp, V., Pooley, J. A., & Whitehead, L. (2024). Living with depression in the family: A narrative inquiry methodology for seeking meaning through stories. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 23. View

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage Publications. View

Kim, N., Kim, S.-J., Jeong, G.-H., Oh, Y., Jang, H., & Kim, A.-L. (2021). The effects of group art therapy on the primary family caregivers of hospitalized patients with brain injuries in South Korea. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 5000. View