Journal of Social Work and Welfare Policy Volume 3 (2025), Article ID: JSWWP-152

https://doi.org/10.33790/jswwp1100152Research Article

The Socio-Economic Impact of Covid-19 on the Seafaring Community: The Case of the ‘Minority Group’ in Shipping

Priscilla A. Afful1, Anthony D. Sackey2*, Bertrand Tchouangeup3, Isaac Eshun2, Raphael Ofosu-Dua Lee4, Benjamin L. Lamptey5, Abigail D. Sackey6, Abraham A. Teye7, Richmond K. Quarcoo8, Josiah Stephen9, Ekow E. Wood10, Kwesi G. Barwuah1, Stephen Amoak11, Marilyn A.Y. Amedzake12, Kofi Ankobiah6, Boaz Danquah13, Barbara K. Sackey14, Nathanael Sackey10, Isaac Eshun2, Enock O. Nyarko2, Pamela Selorm15, and Rosemary Quarcoo16

1Nautical Science Department, Faculty of Maritime Studies, Regional Maritime University, Accra, Ghana.

2Marine & Offshore Division, Bureau Veritas Ghana, Accra, Ghana.

3DNV GL Oil and Gas/Grassfield Maritime Consultants Lagos, Nigeria.

4RROC Industrial Limited, Accra, Ghana.

5National Centre for Atmospheric Science School of Earth and Environment, University of Leeds Fairbairn House, 71-75 Clarendon Road Leeds, LS2 9PH, UK.

6University of South Africa, UNISA, City of Tshwane, South Africa.

7Ghana Navy, Naval Headquarters, Burma Camp, Accra, Ghana.

8Plastic Punch Organisation, Accra, Ghana.

9Federal College of Dental Technology and Therapy, Enugu, Nigeria.

10Bernard Shultz Shipping Management, Accra, Ghana.

11West African College of Physicians, Accra, Ghana.

12School of Medicine and Dentistry, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana.

13Mines Division, Bureau Veritas Ghana, Accra, Ghana.

14Faculty of Legal Studies, Wisconsin University of Wisconsin, Accra, Ghana.

15Ministry of Works and Housing, Accra.

16Department of Clothing and Textiles, University of Education, Winneba, Ghana.

Corresponding Author Details: Anthony D. Sackey, Marine & Offshore Division, Bureau Veritas Ghana, Accra, Ghana.

Received date: 03rd June, 2025

Accepted date: 30th June, 2025

Published date: 02nd July, 2025

Citation: Afful, P. A., Sackey, A. D., Tchouangeup , B., Eshun, I., Lee, R. O. D., Lamptey, B. L., Sackey, A. D., Teye, A. A., Quarcoo, R. K., Stephen, J., Wood, E. E., Barwuah, K. G., Amoak, S., Amedzake, M. A.Y., Ankobiah, K., Danquah, B., Sackey, B. K., Sackey, N., Eshun, I., Nyarko, E. O., Selorm, P., & Quarcoo, R., (2025). The Socio-Economic Impact of Covid-19 on the Seafaring Community: The Case of the ‘Minority Group’ in Shipping. J Soci Work Welf Policy, 3(1): 152.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Before the December 1st, 2020 resolution, the failure of coastal and maritime states to accord seafarers a ‘Key Worker’ status during moments of demonstrated selflessness was evidence of the lack of genuine interest in their concerns. The situation appears worse for the non-traditional seafaring community. Thus, the examination of the response to the general challenges faced by mariners was in comparison to efforts directed towards the world’s minority seafaring community. The case of the African seafarer and the cost of training and certification (STCW 2010) amid the pandemic, is because the year 2020 through 2021 heralds the call for global inclusiveness, and the need for a targeted intervention –a lack thereof contributing to the slow international response and inefficiencies, and poor implementation of COVID-19 interventions. The rising COVID-19 cases, unemployment, job losses, poor mental health, hospitalisation, and eventual deaths have been consequential.

The study employed a hybrid approach, combining remote surveys and direct interviews, primarily conducted online, to examine seafarer concerns. It identified and investigated policies implemented in response to the identified COVID-19 impacts, assessing these based on the various relief interventions offered by stakeholders. The intention was to help determine the best responses in addressing seafarer concerns.

The study found that few maritime institutions currently service global supply shortages. The seafaring community is characterised mainly by people in the age group of 24 to 35 years. The seafarers expressed desperation and raised concerns about exploitation suffered at the hands of criminal elements. Of the number of people who responded to the interview, women constituted fourteen (14) per cent; ninety-seven (97) per cent had their jobs impacted; ninety-one (91.06) per cent supported current calls for IMO-led interventions; almost eighty-two (81.81) per cent approved of a continuation post pandemic; seventy-two (72.12) per cent were dissatisfied with the current cost of STCW documentation, while sixty-one (60.86) per cent sought financial intervention for renewal.

Despite the need for further research studies in areas such as health emergencies, maritime transport, and operations, the study concludes that establishing a framework led by the IMO to support the expansion of the targeted approach to employment for minority groups worldwide.

Keywords: COVID-19 Impact on Crew management, Health Crises on Marine Operation, Policies and Regulations in Maritime, Maritime Operations and Pandemic, offshore Operations in Africa

1. Introduction

Across the world, seafarers have continued to serve in the face of the grave adversity posed by the COVID-19 pandemic and its associated restrictions, ensuring that the global supply of essential goods, including medicine, food, energy, and consumables, remains uninterrupted [1-3]. Many of these seafarers are natives of China, the Philippines, Russia, India, Indonesia, and Ukraine. These countries are known for producing the most significant proportion of the world’s seafaring population. In contrast, Africa as a whole; forms the smallest ethnic demographic grouping [4,5] — hereinafter referred to as part of the ‘minority’ demographic grouping relative to opportunities in the blue economy. The studies also recognise women as part of the ‘minority’ group.

Globally, the blue economy has continued to see growth [1]. This situation has resulted in a shortage of seafarers. [4], estimates a rise in demand to 1,827,735 by 2025 from 1,545,000 in 2015. It is, however, unclear whether the challenges of the pandemic and its associated restrictions will continue to impact the growth of the seafaring population into the future.

This is because, despite the promising prospects of global demand and the positive perception seafaring careers enjoy in the public view, it has been widely reported that there is low interest among young people. Within the last decade, many in the seafaring community around the world, including those of African descent, have fallen out with the ‘life-at-sea’ service. These individuals are unsure whether they made the right career choices, as there are compounding fears over mass quitting attributed to the COVID-19 crisis, as well as crew crises [6-9].

Although all stakeholders recognise the critical role seafaring plays in maritime trade in this era of globalisation and during the pandemic, reports of unfair treatment of seafarers persist worldwide. The news reports suggested some seafarers who fell ill onboard various ships during the pandemic were refused port passes for local medical treatment. Several port states denied permission to some vessels to dock or berth. SOS calls from some ships went ignored by multiple authorities due to COVID-19 [10-12].

These, among many other challenges, led to the great call for the seafaring community to be accorded essential worker status by the UN. Subsequently, after a very difficult and troubling eight-month long wait beginning in March 2020, the United Nations (UN) finally, recognized the need for an urgent and concrete response from stakeholders, hence adopting the December 1, 2020 resolution designating seafarers and other marine personnel as ‘Key Workers’ [13,14].

Despite this recognition, the seafarers' role still receives very little appreciation from decision-makers responsible for international responses to the Covid-19 crisis, and from those responsible for local and national level responses [15] as suggested in the IMO circular letter (4204/Add.35) issued on December 14, 2020, by IMO Secretary-General [13].

The UN, through the IMO, subsequently provided some form of relief to seafarers. The reliefs were designed to impact the training and certifications (STCW) regulations, among others.

It is unclear how beneficial the measures were to the seafarers in general as well as to those forming the minority group, as many were rendered jobless due to the health consequences of the pandemic and the associated restrictions. Others were forced to overstay their contract, with unpaid wages [1]. This is not to suggest that the STCW renewal extension provided through the IMO Circulation, via national authorities, for the renewal of certificates and training, was not helpful.

These increasing difficulties have resulted in a high rate of income loss, loss of interest in the profession, poor mental health [16], marine accidents and incidents, and ill health, in some cases, the loss of lives [17]. The integrated nature of the concerns, suggests a looming crisis during- and after the global pandemic at hand, for international trade, the global supply chain, the maritime community [2,18] and the seafaring profession, whose impact may reflect on the quality of marine operations [18] of the global transportation supply chain.

This study, therefore, aims to explore career interests among seafarers, focusing on the minority group during the pandemic, to develop the most effective recommendations based on an integrated approach for addressing potential growth or shortages in the supply of seafarers.

To achieve this, the study will identify and investigate the current policy implementations and practices regulating the seafaring profession. It will explore some of the challenges faced along the career path. This will include examining pre-COVID-19 challenges and the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on the seafaring profession by identifying and assessing the various measures and reliefs given to seafarers throughout the pandemic by multiple authorities. It will finally attempt to suggest the most appropriate integrated policy measures to ensure the seafaring population remains at the forefront of the global supply chain and thus continues to lead the fight against the coronavirus disease, receiving the recognition and support it deserves. These distinct outcomes will help the world with economic recovery [2] and better prepare for future pandemics and any crises that have the potential to disrupt the global supply chain.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Overview of COVID-19 Health Crises on the Maritime Industry

The study deploys a mixed qualitative and quantitative case study approach while taking into account the general seafaring population across the world in developing its samples, designing the research, and deciding on the most appropriate instrument to be used in the data collection process, as well as adopting the most effective technique for validating data reliability. Therefore, the mixed-method approach of combining survey and observational data in the case study represents a slight modification from [5]. The study’s purpose highlights the sensitivity and emotional framework that can capture the seafaring community’s experiences.

2.1 Design and Scope

The descriptive design employed here is based on slightly modified [5] assumptions, which involve incorporating observational data. The survey deployed shall elicit analysis of responses given by participants administered through interviews or questionnaires. Due to the ongoing health crisis, all interviews and questionnaires were administered through various online Portals, such as direct email listings, were also shared with respondents on various social networks, including LinkedIn, Telegram, and Facebook. The survey lasted for two months, from late February to late April 2021.

The study is driven by specific critical questions raised in the introduction and supported by the assumptions that the disappearance of national shipping lines particularly of nations in West Africa in the mid-1990s, when maritime transport was liberalized globally [19] did provide a prospect for African seafarers as international tradesmen in a profession already dominated by people of Asian descent. The seafaring trade, which men have generally dominated for thousands of centuries, is today forced to embrace diversity on all fronts; therefore, the study examines the trend among African women.

2.2 Study Area

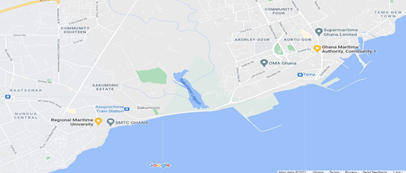

Researchers in furthering their understanding of the current trends of COVID-19 on training and certification of seafarers visited two key sites for their field observations. These factors took into account the institutions' proximity and the distance of their coverage in terms of service to seafarers. The campuses of the Regional Maritime University and the offices of the Ghana Maritime Authority (GMA) are all located in Accra, the regional capital of Ghana (see Fig. 1). These institutions by default under the MOWCA memorandum of understanding provides standard training and certification for citizens of West and Central Africans with the support of the governments of the Gambia, Liberia, Cameroon, Sierra Leone, and Ghana as well as support from the World Maritime University.

Figure 1: Map of the eastern Coastal section of Greater Accra showing locations of the Regional Maritime University and the Ghana Maritime Authority in the Greater Accra region, respectively. Courtesy Google satellite, 2021

2. 3 Target Population Sampled

The seafarers, alongside other critical marine professionals in the offshore energy and marine food industries, are randomly selected for the study, with a particular focus on Africa. These are those the study believes their duties have remained relevant in the face of the pandemic, and therefore impacted by the economic fallouts, health risks, and the various measures and protocols put in place. The population also encompasses both maritime shipping and offshore oil and gas seafaring professionals.

Focus, however, was on black Africa, bounded by the Gulf of Guinea coast (encompassing West and Central African nations), whose initial maritime ventures sought to provide crewing for national shipping lines in the years following independence, driven by a desire for national pride. Furthermore, the African female segment of the seafaring community will be engaged to share their experiences and insights about the impact of COVID-19 on their careers.

2.3.1 Ethical Considerations

All respondents were informed of the intended use of the data provided and were allowed to express their thoughts freely, provided that the reported findings were unanimous. These were essential to the urgency and intent of the study, as it applied an integrated approach to addressing the emerging concern of the African seafaring community amidst the pandemic.

2.4 Sampling Technique

A purposive or judgmental Quota sampling method was used. The purposive and quota sampling used is based on selected elements and time limitations placed on the research data gathering process. Seafarers typically have a short window of opportunity when their ships call at ports or offshore facilities, allowing them access to adequate internet or telephone facilities to interact with others. These, among other constraints, were taken into account during the design process.

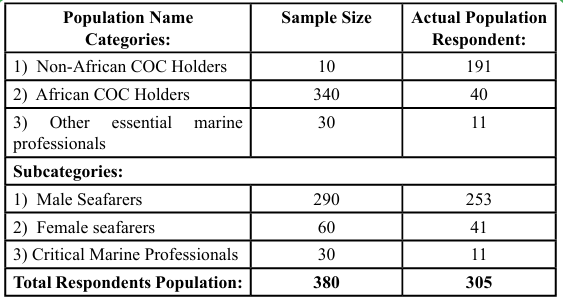

2.5 Sample Size

The population sample chosen is as shown in Table 1. The 2015 estimate of the global supply of seafarers, according to [3], stood at 1,647,500, with African seafarers generally constituting 2 per cent of this population [19], giving 32,950 seafarers supplied from across Africa. At a 95 per cent confidence interval and an error margin of 5 per cent, the sample size of three hundred and eighty (380) respondents was obtained, for which the various contributing categories are as indicated in Table 1 below.

Of this pool of respondents, a few will be engaged in interviews to provide a detailed account of their experiences.

2.6 Data Gathering

The instruments used in this research were questionnaires, personal observation, and a review of secondary data related to the subject matter. The instruments chosen were deployed through various platforms, including mobile phone calls, online text platforms, and social media platforms such as WhatsApp, Google Forms, SurveyMonkey, and Facebook Messenger. The survey was shared on various online groups and pages dedicated to the seafaring community. Various literature materials, including online articles, journals, webpages, and news, were also cited. These approaches were imperative due to Covid-19 health risk, protocols, and regulations including various social distance requirements, travel restrictions, and heightened health risks following the varying new strains (such as the South African, and the Brazilian variant) currently being witnessed (i.e., from 2021 to 2022) as a surge of the second and third wave across the world. Additionally, recognising that the researchers could not travel to meet every seafarer, the use of the aforementioned tools was deemed appropriate to sample the selected population.

The process lasted for two months, mainly relying on the internet facilities of researchers and respondents.

Following the easing of restrictions, a field survey was conducted at two critical locations frequently visited by seafarers. This allowed researchers to sample individuals visiting the offices of the Ghana Maritime Authority for documentation and renewals, as well as training centres for STCW 2010 certification and training.

2.7 Data Analysis

The analysis of the study employed graphical presentations, tabular extrapolations of figures, and descriptive observations to highlight the study's objective. The analysis will be further developed based on a supportive comparative argument –a technique relied on by [20].

3. Results

The results presented in this section comprise both primary and secondary findings gathered within the study's time frame. These are presented in subsections as they relate to the study's ultimate objectives.

3.1 An Overview of Africa’s Maritime Industry concerning Seafaring Engagement

According to [21], in 2021, one year into the COVID-19 pandemic, Africa's maritime trade totalled 1.3 billion tons, representing an increase of up to 5.6 per cent over the 2020 record. Almost seven (6.9) per cent of total goods were loaded and 5per cent of total goods were discharged. In contrast, for containerised South-South trades, such as those between Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean, the figure was 12.5 per cent. For the North-South corridors, such as Africa to Europe, it accounted for 7.8 per cent due to labour strikes that affected the ports and logistics sector in South Africa. These events contributed to further disruptions in the supply chain, a key feature of the global economic recovery in 2021 and 2022 [21].

Concerning maritime fleets in the region, [21] underscored that the top three flags of registration, in terms of dead-weight tonnage and commercial value, included Liberia, which had the highest increase in share value of its fleet as of January 1, 2022, by 2.2 percentage points.

Historically, Africa’s fleet is constituted by the oldest bulker, container ship, and oil tanker vessels, according to [21], although with a limited pool of fleet ownership [21]. Further asserted that, though many years have witnessed efforts at increasing African participation in the supply of shipping services, not much progress has been made or sustained. The continent still heavily relies on foreign owned vessels for domestic and international logistical needs [21]. Recognises that the need for environmental regulations compliance and open market competitiveness raises the stakes higher for Africa, making African ownership even more challenging. Along some routes, the deployment of greener ships may also leave the continent with associated higher operational costs, making their operations unsustainable. Again, some countries, such as South Africa, Egypt, and Morocco, have a well-developed transportation infrastructure. These countries believe they have the potential to supply alternative energy, and plans are well underway to provide bunkering services to greener ships [21].

Regarding the maritime workforce, it is a matter of public knowledge that sub-Saharan Africa faces challenges of unemployment and insecurity. Youth unemployment in Africa, according to [22], was estimated at 34 million individuals (7.5 per cent of whom are women) in 2019. In Western Africa, women's unemployment was 6.6 per cent compared to 5.6 per cent for men. Poverty among the youth stood at sixty-three per cent of young workers [22]. The statistic shared above is no different from that of the maritime industry. The mere cost of training is a disincentive for the larger pool of the African population under the poverty margin. These suggest that many companies, including those established in the maritime industry, were either taking advantage of the oversupply of labour due to inadequate job opportunities and infrastructure to pay lower wages for their services or rationing labour in ways that contravene labour regulations. The sector also grapples with employment recruitment scams for networks of criminal syndicates [23].

Concerning the issues of security, the Gulf of Guinea remains a crucial maritime trading route with an excess of 1,500 vessels (consisting of fishing vessels, tankers, and cargo ships), navigating its waters daily in a routine [24]. Additionally, the 880,000 square miles coverage of the Gulf, bordered by over a dozen West African countries, ordinarily creates opportunities for gaps in naval patrols and other difficulties in maritime logistics, jurisdiction, and communication. However, the Gulf has experienced nearly a 50per cent increase in kidnapping for ransom incidents between 2018 and 2019, and a further 10 per cent increase between 2019 and 2020 [24]. They reiterated that many of these pirate groups have graduated from simple oil bunkering (the armed robbery and/or siphoning of oil cargoes) into the seizure of vessels and kidnapping of ship crews. Kidnapping and ransoming crews is today a more lucrative piracy strategy (with an average ransom of $50,000 per crew member) since the 2014 crash in oil prices [24]. It is unclear whether these rising incidences of insecurity have a direct relationship with seafarer unemployment across the region, particularly due to lapses in security, surveillance, and monitoring. This is worthy of investigation.

These insecurities instigated the Ghanaian Navy to spearhead new efforts at improving regional cooperation, maritime domain awareness (MDA), information-sharing practices, and tactical interdiction expertise in the Gulf of Guinea through a range of international naval exercises. This led to Ghana hosting the Oban Game Express 2021 (OE21) in March 2021. It is the largest maritime exercise in Western Africa. On another breath, the Nigerian Navy has also remained very active in the domain with newer military acquisitions, trainings, and designed operations of counter piracy and illegal maritime trading along the GoG corridors [5]. However, [5,25] also further assert that the number of piracy incidents has begun to slow down in the region.

Concerning maritime prospects, [25] among others, believe that the current implementation of the African Continental Free Trade Agreement presents an opportunity for greater trade among countries within the various regional blocs on the continent. They highlight the need for a detailed framework to be established to push this agenda across the continent. The success of this program is expected to boost fleet ownership in Africa and scale up the maritime workforce, thereby reducing the level of unemployment among the continent's youth, who comprise the largest segment of the population.

3.2 Critical Policy Regulations Affecting Seafarer Engagement amid the Pandemic

Various legislative frameworks govern the employment of seafarers on board ships. Key amongst these frameworks is the International Convention on Standard Training, Certification and Watchkeeping STCW 1978 with major revisions in 1995 and 2010; Maritime Labour Convention MLC 2006:2010, and the International Ship and Port Security Code ISPS which are discussed in brief detail below. Others, such as SOLAS 72, COLREG 83, and MARPOL 73, are regulations that govern the operations on board in line with safety and sustainability.

3.2.1 The Standard Training Certification and Watchkeeping, STCW

For STCW, the focus is on the competency development of personnel to be assigned on board. According to the International Maritime Organisation [15], the 1978 STCW Convention established basic standard requirements on training, certification, and watchkeeping for seafarers on an international level – a task previously determined by individual governments, without reference to practices in other countries. As a result, standards and procedures were harmonised, given the international nature of all industries. Thus, specific minimum standards regarding training, certification, and watchkeeping of seafarers were prescribed, for which countries are obliged to meet or exceed [15]. In other words, the obligation was on the flag state and national administrations to ensure that ships under those flags met the minimum threshold in the convention. This involved the establishment of training institutions, certification bodies, and evaluation and verification processes to operationalise the regulations.

This convention establishes a clear pathway for individuals worldwide to build careers in the shipping industry, starting with foundational proprietary education and training. However, maritime training institutions are limited in number worldwide due to the high costs associated with them. This is particularly the case in Africa. Though there are growing numbers seen providing maritime training, a few notable naval training institutions set up by local governments, such as the Nautical College of Ghana in 1958— now the Regional Maritime University (RMU) since 2007 [26]; the Regional Academy of Science and Technology of the Sea of Abidjan (ARSTM) – a training centre for West and Central African francophone countries in West Africa; the Arab Academy for Science and Technology and Maritime Training Institute (EMTI) in 1972; the Maritime Academy of Nigeria in 1979; the Federal College of Fisheries and Marine Technology in 1992 [27], were specifically setup to provide seafaring training to aid in crewing national shipping lines which dominated the era during the time after independence from colonial rule. The Black Star Line (BSL), a state shipping corporation of Ghana (named in honour of Marcus Garvey’s line of 1919-1922), with 16 ships, was one of the pioneers of state shipping lines in sub-Saharan Africa. Like most national shipping lines in Africa, the trade volumes did not justify the number and capacity of assets, leading to the sale of ships [28].

The eventual collapse of the national shipping lines on the African continent did not end the operations of training institutions; however, the focus was shifted to meeting crewing needs on the international market [29-31]. The shift in focus has since led to the establishment of new institutions and the expansion of existing ones among several training partnerships. The Regional Maritime University (RMU), having refocused its purpose, is designed to serve the West and Central Africa Anglophone region by training seafarers under the ECOWAS protocol, spearheaded by MOWCA (Maritime Organisation of West and Central Africa). Despite these challenges, most seafarers trained in African-based maritime training institutions, before the Covid-19 pandemic, struggled to find seagoing employment opportunities compared to their counterparts in Asia, Europe, and the Americas, and this situation has worsened even further under the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic.

3.2.2 The Maritime Labour Convention, 2006 (“MLC, 2006)

For the Maritime Labour Convention, 2006 (“MLC, 2006”), the focus was on establishing the minimum working and living standards for which seafarers could inhabit and work on ships flying the flags of ratifying countries [32]. The International Labour Organisation (ILO) also asserted it remains an essential step in providing a level playing field1 for owners and countries undercut by those who operate substandard ships. The economic value of the maritime industry encompasses infrastructural development, competency building and professionalism, employment provision, foreign exchange earnings and remittances, foreign investments and trade opportunities, as well as technological transfer and training. Seafarers, on the other hand, are often forced to work under poor conditions, which negatively impact their health, family life, and overall well-being.

The challenges observed during the pandemic appear to have instigated several changes that align with the maritime labour concerns widely reported in the news over the last decade. According to [33], the Special Tripartite Committee (STC) adopted amendments at its third meeting, which were approved on 6 June 2022. The approval was by an overwhelming majority of delegates during the 110th session of the International Labour Conference. Subsequently, member states were notified of the amendments on 23 June 2022, in line with Article XV, paragraph 6, of the MLC, 2006. The amendments are expected to take effect on 23 December 2024, under Article XV, paragraph 7. The proposed amendments included:

1. Resolution on Harassment and Bullying, including Sexual Assault and Sexual Harassment, in the Maritime Sector

2. Resolution on contractual redress for seafarers

3. Resolution on financial security

These resolutions are said to reduce or eliminate some of the abuses within the industry. They may go a long way to improve standards for individuals within the minority groups, such as those from third world countries, Africans and women seafarers. Though Africa provides the world with only 2 per cent of the ocean's labour force, this figure is significant in meeting the global demand and supply of seafarers. It is therefore not for no reason that governments in Africa have seized the opportunities in the international labour market for seafarers to reduce local unemployment among potential graduate students by enacting local content (LOC) laws for the offshore oil and gas industries. These measures have afforded the training of local subsea engineers, subsea surveyors, drillers, Riggers, Deck Foremen, shift supervisors, instrumentation engineers, remotely operated vehicle (ROV) pilots and technicians, certified welders, among others. Additionally, the sea terms required in the training of marine deck officers and engineers, from the cadet level through the ranks, have become accessible to many who would have otherwise struggled with unemployment before the LOC (Local Content Law) regulation. Realising the full potential of a seafarer comes from the opportunities available to them and not just the academic knowledge they acquire in educational institutions. Unfortunately, almost all maritime training institutions in Africa lack training ships to support competency building. Calls to help in this regard have not yielded the desired results.

For these individual respondents, becoming who they are, that is, sailors aiding the transportation of goods and services from various locations across the world, while serving as a lifeline [with eighty per cent of trade volumes [1,2], was an essential component of their work. However, providing the much-needed supplies that currently sustain the world economy in the fight against COVID-19 through these unprecedented times remains the motivation for the future. Recognizing the sacrifices of seafarers today, whether bound to the maritime shipping industry or bound to the offshore oil and gas, and renewable energy industry; they are ensuring globally that there is in constant supply: food, health care consumables such as Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), Covid-19 vaccines and therapeutic medicines, and needed energy supplies to mention a few, required to win the battle against the global pandemic do not grind to a halt, not for a day regardless of any health risks they face. Thus, in so doing, they have helped and continue to avert a global calamity.

3. The International Ship and Port Facility Security, ISPS Code

For the International Ship and Port Facility Security Code, priority is given to the level of the safety and security of ships, ports, cargo and crew [34]. According to [35], maritime security is of paramount importance to the operation of vessels and therefore, the coming into force of the International Ship and Port Facility Security (ISPS) Code2 On July 1, 2004, it was essential. While several security measures have been established in ports, offshore facilities and on ships, the problem of armed robbery and piracy continues to grow, especially in sub-Saharan Africa [5]. It appears that the pandemic and associated restrictions did not slow the impact of maritime crimes in the Gulf of Guinea. Several seafarers were taken hostage, as reported by the ICC IBM. Many efforts have been made at the local, regional, and international levels to mitigate the risks faced by seafarers in the region. Some researchers believe the current efforts against piracy are not enough, and the state of reporting does not reflect the real levels of crimes taking place in the maritime corridors. However, since the pandemic, the need to ensure change has come to the forefront through various calls made by relevant stakeholders across multiple facets of international dealings [25].

Nonetheless, issues affecting seafarers (trumpeted by the ‘crew crises’) have received some attention, however little it may be; there are growing calls [13,14]. Despite these considerations, most local and national authorities have yet to respond to the various calls instigated among industry players, such as the International Chamber of Shipping (ICS) [17] and the International Maritime Organisation, as signatories to the IMO Circular (4204/Add . 35) letter. Only a dozen of the fifty-five out of the 174 IMO member states and one associate member country including Singapore, whereas in sub-Sahara Africa, Ghana, Liberia, Kenya, and Nigeria have implemented the IMO circular letter (4204/Add.35) resolution [14,36], these view maritime professionals, particularly seafarers as ‘key workers’ or ‘essential frontline worker’ and have acted and continue to act accordingly with policy decisions and directions amid the crises.

3.3 Concerns Affecting Seafarer Engagement

In Africa, the COVID-19 health crisis is compounded by a growing maritime security crisis, marked by an increase in pirate attacks [5,37] on the high seas and within the Gulf of Guinea sub-region. The issue of maritime professionals, particularly seafarers, being treated as a non-essential workforce amid insecurities, as is the case among many countries today, opens a grave wound of deprivation. This concern strikes at the heart of the seafaring profession, making it a less attractive choice for many.

The issue of unemployment among the maritime population in Africa appears to be high, given the high turn-out ratio of the trained seafaring population and the limited opportunities available. These concerns require immediate pragmatic solutions, given the high cost of training involved. It is, however, unclear if there are any linkages between issues of unemployment of seafarers in the region and the growing crisis of maritime insecurity, such as drug peddling at sea, armed robbery and pirate attacks. It is essential also to note that some researchers, including [5], have suggested the situation of unemployment as a breeding ground for criminal syndicates in their operations.

Whereas these may not be the case for many, there is also the challenge of recruitment scams [23,38] and human trafficking on the rise within the region [39,40].

3.4 Empirical Findings

The results presented below reflect respondents' current disposition on the very pertinent matters shaping maritime careers, training, and the overall economic well-being of African seafarers before the onset of COVID-19 and amid the ongoing pandemic. The survey, which commenced in late February, continued into May 2021 before concluding. The study appears to have generated considerable interest among as many African seafarers as possible. These findings from the survey are therefore examined in line with the demographic information of the respondents, while drawing comparisons on consented issues affecting the African seafarer amid the COVID-19 crisis.

3.4.1 Background Demographic of Respondents

The 2 per cent of the world pool of seafarers composed of the African seafaring community [19] today, is made up of people of diverse nationalities, ethnicity, and gender as well as personality types. These figures ordinarily project the African sea labour force as the world’s ‘minority group’ within the social arena. Therefore, like any human race group across the globe, it is expected that this dynamism within the population will shape the progress of African seafaring in the decades to come as the world calls for more inclusiveness in global wealth creation. The demographic information took into account the age, gender, nationality, and family support.

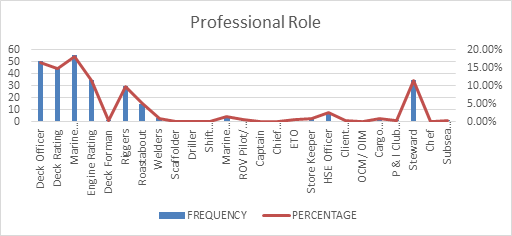

Figure 2: Age distribution of seafarers who responded to the system, and professional roles within the maritime occupation. See Fig. 2 and Fig. 3 for the age and gender groupings of the sampled respondents.

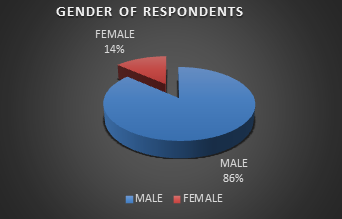

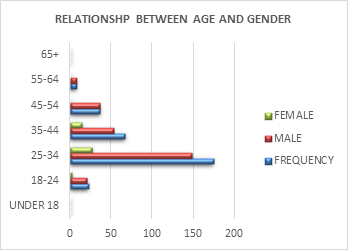

From Fig. 2, the ages of respondents fell within eighteen (18) and sixty-four (64) years; however, the most dominant age group was between 25 and 35 years (representing 57 per cent of respondents). This dominant age group fairly reflects Africa's characterisation as the ‘youthful continent’, with a young and vibrant population in the 21st century, compared to other continents. This also demonstrates the great interest in the profession among young Africans, who today have the opportunity for unlimited education. The countries of those interviewed are also indicated in subsequent paragraphs. According to STCW stipulated guidelines, the minimum education required for a seafarer is the middle school level; however, the larger pool of young African seafarers had advanced levels of education in various fields and only diverted their career interests into the maritime industry.

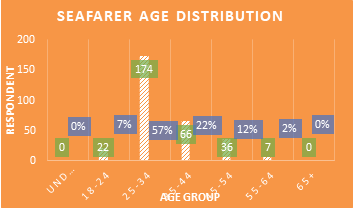

Most of these young seafarers demonstrated great optimism, despite the significant unemployment gap across the African continent. Regarding the gender of respondents, the trends shown in Fig. 3 are similar to those observed among most professions involving STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) fields.

A comparison was made between age and gender, which followed a similar pattern. This is shown in Fig. 4, the ages of female respondents were found to be, instead, averaging 26 years within the age group of 18-24 years and 25-34 years. This period marks the transition from college to the beginning of their first job adventure for the young sailors. The trend also suggests a decline in interest in the career for women beyond the age of 35, who may take on other responsibilities related to family needs and childbirth.

Female respondents only constituted 14 per cent—those with STEM backgrounds made up 3.61 per cent, and the remaining 10.16 per cent had non-STEM backgrounds (mainly Stewardesses on board offshore construction vessels). Currently, it is unclear whether there are sufficient studies on the trend analysis of women working on traditional oceangoing vessels and offshore marine vessels. Given that 2020 appears to be the most eventful year, heralding a call for inclusiveness in the world, especially for Black lives and females, the study considers the side issues raised by these respondents as critical to maritime stakeholders and the IMO’s mandate, and therefore reflects them in these findings.

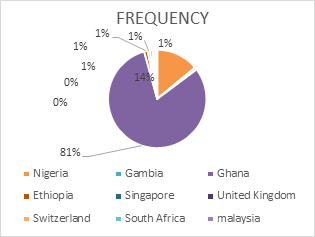

Of the 305 individual respondents sampled over the two months during the field surveys in the study, Fig. 5 shows the dominant roles, and Fig. 6 shows various nationalities and the national maritime authorities represented, respectively, though a few respondents chose not to enter such details. This data, however, does not encompass the many dozen national naval authorities in Africa due to limited access and contacts.

The diversity found within the African seafaring community is primarily observed in the offshore industry, where governmental interest served as a natural catalyst, ensuring that local crews were engaged on oil fields. This remains a laudable policy and will ensure more inclusiveness for both Africans and women in general, according to respondents. The various local content laws implemented by African nations are ensuring that most seafarers meet the required sea terms while helping to train others in various non-traditional STEM roles onboard ships, as highlighted in Fig. 5.

Overall, Ghanaian respondents were the largest responsive group in this study due to the proximity of the location to researchers (see Fig. 6). Other factors such as travel restrictions may have also contributed to the low number of non-Ghanaians, as other African nationals trained and holding Ghanaian certificate of competency (COCs) were relatively hard to locate on and around RMU campus amidst the pandemic. The location of RMU means that Ghana benefits from receiving students from across the entire African sub-region, including some non-Western and Central African nation-states identified in Fig. 6, particularly from Ethiopia. In contrast, some respondents held dual seaman discharge books, obtained through documentation from the training country, in addition to their national discharge books. Other respondents of African descent held COCs from the UK and Singapore, reflecting the diverse training regimes to which they were exposed. The respondent indicated it brought some ease in securing jobs.

This background in the study comprehensively characterises the seafaring community, regardless of the stated margin of error or sample size, although not all African states are represented. With this, characterising the background of the seafaring community, researchers proceeded to inquire of respondents about their current status as seafarers amidst the raging COVID-19 pandemic. Their responses are highlighted in the preceding paragraphs.

3.4.2 Impact of COVID-19 on JOBS and Workers' Morale of Seafarers

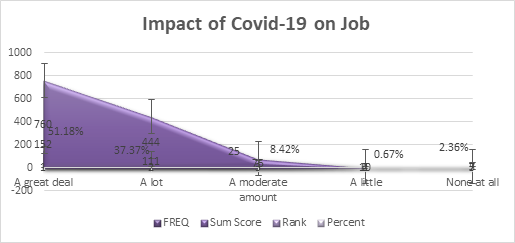

Respondents were asked whether one of the current impacts of COVID-19 was affecting their jobs, and if so, to what extent. Of the 305 respondents, only 297 responded to the query, for which the results are shown in Fig. 7.

The total point score was 1,296, with a median of 75 (s.e. 149.0951) and a mean value of 259.2 (Confidence Level (95.0%) = 413.9542783). From the results in Fig. 7, 297 respondents, representing 97 per cent of all respondents, expressed concern, with a majority of 96.97 per cent indicating that they had suffered various degrees of impact from the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, 51.18% of the respondents were confident that COVID-19 had a significant impact on their jobs. The majority explained that their unsuccessful job pursuits and unemployment predicament were a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Some bemoaned the fact that they had not been in employment for almost 2 years and counting. Again, 111 respondents, representing 37.37 per cent, indicated that the impact had been severe on their job. They listed travel restrictions, high cost of travel and loss of contracts as some of the problems they encountered over the period. To them, these situations caused their families considerable suffering. The remaining 8.42 per cent and 0.62 per cent of respondents shared their concerns as moderate and slight, respectively, claiming that this struggle was primarily due to delayed embarkation, suggesting that these challenges were to be expected during any pandemic. Therefore, it was incumbent on us individuals to adapt to changes that bring us some amount of relief. Only 2.36 per cent of respondents indicated that their jobs were not affected by COVID-19 at all. The results revealed that all these individuals remained engaged in their various jobs from the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

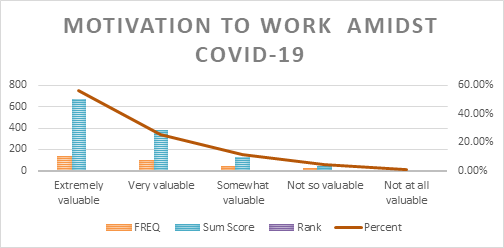

With these findings, researchers sought to determine the current level of work motivation among the seafaring community and marine professionals. They were asked whether they found it imperative to work amidst the health crisis. They were asked to note the changes in other industries, such as working from home and a shift system where jobsites cannot be avoided, as well as recommendations from health experts and policymakers encouraging a stay-at-home culture to combat the pandemic. The findings are shown in Fig. 8.

The total point score was 1,223, with a median of 126 (standard error = 276.2332348) and a mean value of 244.6 (Confidence Level (95.0%) = 342.9888627). Notably, over 56 per cent of the respondents found the need to work to be paramount. This was supported by over 30 per cent and 10 per cent of respondents who felt it was very valuable and somewhat valuable, respectively. To them, staying at home and not working was not possible and could have led to them suffering from depression. This also indicated that they had no other skill set that could make them gainfully employed working from home. Others bemoaned the cost of their training and certification renewals as a reason they had not been able to invest in any profitable venture before the COVID-19 pandemic, and this issue has only been exacerbated as they remain unemployed today while their renewed STCW 2010 documents gradually expire. These struggles of all seafarers, especially minority groups, needed urgent attention from the IMO, some respondents suggested—claiming there was no level playing field in the industry when it came to job opportunities. However, they noted that the cost of certifications was a factor, which they considered unfair.

However, less than 5 per cent of respondents indicated that they did not need to return to working on the ship, as it was not particularly valuable. These were respondents who claimed to have other engagements beyond seafaring. This changing attitude among the under 5 per cent raises concern that the aftermath of COVID-19 may inspire a mass exodus of younger seafarers (sailors) or serve as a demotivation for many others. These are certainly reasons why any form of support given to seafarers plays a crucial role in ensuring the industry remains well-sustained for the future. The researchers, therefore, examine some of these considerations in subsequent paragraphs.

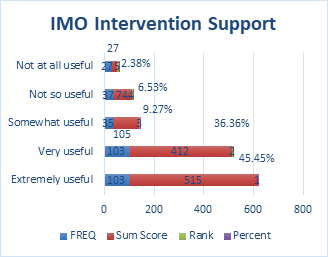

3.4.3 Covid-19 Relief Support Wade Against the Seafaring Community’s Immediate Concerns

According to [1], several African countries have implemented interventions in response to the plight of seafarers and marine professionals since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, despite the slow pace of these initiatives. Notable among the interventions is that established by the IMO, via IMO Circular Letter (No.4204/ Add . 14/Rev.1 5) aiding crew change, and IMO Circular (4204/Add . 35) declaring the seafaring and marine professionals, ‘Essential Workers'. Therefore, researchers herewith examine respondents support for IMO’s intervention with regards to the suspension of certification renewals for seafarers (per circular letters issued to member states, such as CL.4257 issued to Ghana on April 7, 2020) with expired licenses and certificate who were already on board and had to also serve beyond the period of their contract due to heavy travel restrictions. IMO CL4204/Add.193 Was issued on June 2, 2020, to all member-states in this regard, besides individual IMO nations' state requirements addressed with separate CLs. The findings are presented in Fig. 9. The total point score totalled 1,133, with a median of 105 (s.e. = 98.85878818) and a mean value of 226.6 (Confidence Level (95.0%) = 274.4759985).

According to the chart in Fig. 9, 91.06% of respondents provided varying degrees of support for the various interventions implemented by the IMO, whereas 8.94% were not satisfied and therefore did not offer their support. Essentially, as high as 45.45 per cent indicated that the measures implemented to halt the renewal of seafaring documentation for three months, subject to changes due to the raging pandemic, were beneficial. These were supplemented by 36.36 per cent and 9.27 per cent of respondents' scores, respectively, who also considered the measures to be very useful and somewhat helpful. Some of these individuals were currently unemployed and did not directly benefit from the measure. However, the lower percentage of respondents, at 6.53% and 2.38%, who had remained unemployed over the period before the study, held dissenting views. According to them, while their COCs, COP (Certificate of Proficiency) certificates, and medical certificates were expiring without jobs, their counterparts onboard stood to benefit from these waivers at their expense, with no additional funds. Some suggested that the measure aided seafarers from nations that dominated the industry, compared to minorities who already had difficulty breaking into mainstream employment, as shipowners left far beyond their shores. These assertions, though unverified with any literature, raise legitimate concerns that deserve IMO’s attention. The researchers, therefore, proceeded to inquire if they would support the extension of these current measures by the IMO. The results are indicated in Fig. 10.

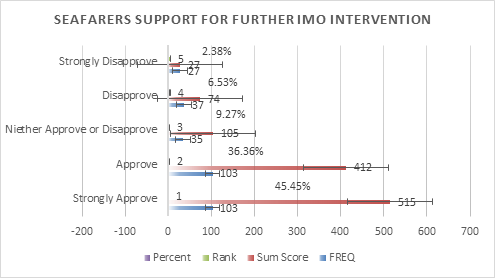

Similar to the earlier inquisition, responses followed the same patterns, with a sum percentage of 81.81 approving its extension, while a sum percentage of 8.91 disapproved of its continuation. 9.27 per cent of the respondents, however, were unsure of the decision and therefore remained neutral in their thinking. With these outcomes in mind, researchers proceeded to investigate financial intervention as a potential motivation that respondents would desire if offered. Such an offer has traditionally been the domain of national governments and institutions to which individuals are affiliated [41-43]. Findings are presented in the next section.

3.4.4 Concerns on Governmental Intervention for Training & Certification amidst Covid-19

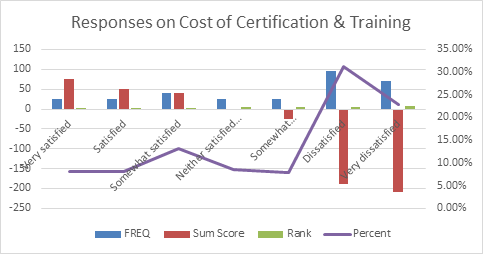

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the economic fallout has been massive, impacting the world economy, every national economy, businesses, and individuals. These have called for several interventions implemented by various national governments. However, these interventions have varied from country to country. In Africa, several similarities are evident, particularly among West African nations, in their approach to combating a pandemic while providing economic relief to their citizens. Ghana, a case in point, provided electricity and water bill payment relief for over three months in 2020 [44] [45]. Other financial support was provided to essential healthcare workers in the fight against the pandemic, while food supplements, such as rice, were distributed to low-income homes. For the seafaring community, also considered essential workers, the researchers sought to determine if there have been other interventions directed at them (such as reduced costs in certifications) beyond ‘goodwill’ and solidarity messages that have satisfied them across Africa. Results are shown in Fig. 11.

From the results, as high as 31.15 per cent were dissatisfied, compared to 22.91 per cent of the respondents who were very dissatisfied with the government’s ‘lack of interest’ in considering it, as they termed it. They explained further that they are well aware of their government's support for the various IMO declarations since the COVID-19 pandemic. Still, actions like cost reduction, which are necessary to ensure such declarations are optimised adequately in the workings of the seafarer and marine profession, are neither here nor there. Some suggest the lack of interest is a result of non- maritime experts operating institutions that require some special maritime considerations and collaborative efforts with the seafaring community as stakeholders. Together, 61 per cent of respondents were dissatisfied with their governments, suggesting that the issue predates the COVID-19 era and has been exacerbated at this time. Only 29.51 per cent of respondents were satisfied with the larger pool of 13.11 per cent, indicating that they were somewhat happy. These calls for attention highlight the need for a pragmatic approach to addressing seafarers' challenges.

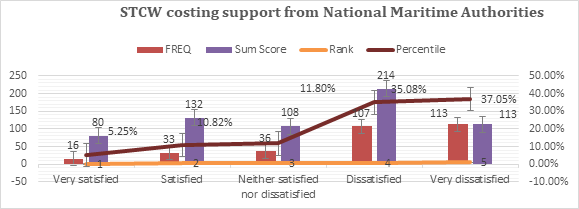

The researchers then assessed the level of support for the current cost of STCW and other mandatory documentation among national maritime authorities in West Africa. Noting that the Ghana Maritime Authority, through the Regional Maritime University, had, under MOWCA, provided extended services to nationals besides Ghanaians, such intervention could be placed into the proper context if ever considered. However, Figure 12 provides details of the findings.

From the graph, 72.18 per cent of respondents, to varying degrees, were dissatisfied with the current cost and would have wished for some rebate or reduction. 11.80 per cent could not determine whether they were satisfied or not; however, 16.07 per cent indicated, to varying degrees, that they were satisfied.

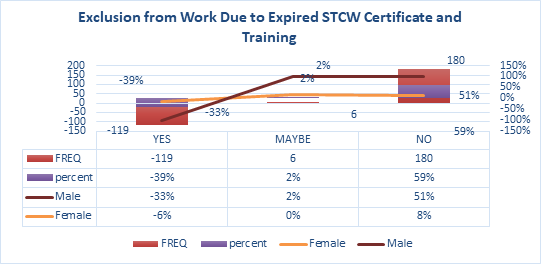

The researchers inquired if any had lost their jobs as a result of any expired certificates or training. Results are shown in Fig. 13.ional development and confidence building for frontline staff.

According to Fig. 13, 39 per cent (with 6 per cent being women) indicated that they had lost their jobs or remained unemployed due to expired documentation. Fifty-nine per cent indicated they had no situation of job loss as a result of expired documentation, from which 8 per cent were women. 2 per cent, however, were unsure if they might have lost jobs at one point in time as a result of not having to renew their documentation before expiration.

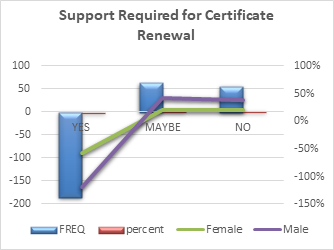

Therefore, researchers inquired further based on their responses, if any had impending renewals and whether they may require some form of financial support from the government or employers. The findings are illustrated in Figs. 14 and 15.

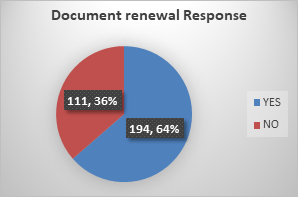

According to the chart in Fig. 14, 64 per cent of the respondents indicated that they had various mandatory documents that had expired or were due to expire and therefore required renewal. Others did not reveal; however, the rest of the 36 per cent indicated they had no renewals for the time being.

Regardless of these outcomes in Fig. 14, responses regarding whether they would require some form of financial support for renewal (in Fig. 15) showed a high of 60.86 per cent in favour, with 18.42 per cent opposed. 21.05% of respondents were unsure.

Of this data, among the 42 women who responded, 57 per cent indicated they will need support, while 21 per cent indicated they may or may not need support. The rest, constituting 12 per cent, were sure they would not need any financial support towards document renewal. The trend was similar to that observed in the males’ responses on the issue.

Researchers upon understanding the burden economic and emotional or otherwise social and psychological burden the seafarers were currently going through as have been widely reported since the onset of Covid-19, thus of the ‘crew crises’ brought about as a result of [14,16] travel restrictions, leading to crew stranding, overstay at home or onboard, loss of income they proceeded to investigate respondents concerns of Covid-19 on their health and the health of those closest to them.

3.4.5 Notable Challenges Currently faced by the African Seafarer group

The health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on seafarers has been recently examined, highlighting current global concerns regarding the inclusivity of minorities in all spheres of business, education, and politics. Efforts to achieve set goals appear to have gained ground for minorities in developed countries amid the pandemic; however, this is rarely the case for African seafarers on the continent, who today make up about 2 per cent of the world’s international shipping labour force. The situation is even worse for African women, who, today, dare to venture into the not-so-traditional trade of seafaring, courtesy of the improved educational opportunities of recent decades.

Generally, a series of health concerns have been raised by various scientists worldwide, including [16], who investigated crew members of a cruise ship. Findings clearly illustrated that seafarers were, however, not immune to the various Covid-19-associated health crises observed among all demographics, occupations and social cycles. The results of this study, therefore, showed that members of the seafaring community in Africa had contact with individuals who tested positive for COVID-19. However, only 18.36% of the total respondents were willing to discuss these issues. Sixty-two and a half per cent of them indicated that they did not observe any incidence of a positive COVID-19 test at their workplace. Again, of the 19 per cent who responded to the query out of the 305 respondents sampled, 69 per cent said no, they had never tested positive nor had any close relatives of theirs tested positive for the COVID-19 virus.

4. Discussions

4.1 Covid-19 Policy Interventions for Seafarers and Fallouts

Despite the current impact on seafarers and various populations worldwide, several stakeholders have implemented interventions to alleviate the burden on individual groups. The notable interventions for the seafaring community across the world came from the IMO and supported by proactive member states; issuing various Circular Letter (CL) such as (No.4204/Add.14/Rev.1 5) aiding crew change, and CL (4204/Add.35) declaring the seafaring and marine profession an ‘essential workers’, extension for certificate renewal for those onboard and could not disembark in time, among others. Essentially, 91.06 per cent of respondents indicated with various degrees of support for the interventions implemented by the IMO, while having an 81.81 per cent degree of approval for such further interventions, whereas 8.91 per cent did not support the measures, and 9.27 per cent neither approved nor disapproved of any additional intervention of that nature. According to these individuals, who all found themselves at home at the time of the survey, while their renewed STCW Certificates of Competency (COCs), Certificates of Proficiency (COP) certificates, and medicals were expiring without jobs, their counterparts onboard stood to benefit from these waivers at the expense of replacing them as off-signers. Reasonably, the situation tilts the income-cost benefit analysis against them. Others suggested that the measure favoured individuals from dominant seafaring nations and the male gender in the industry, compared to minorities of African descent and women, who already faced difficulty breaking into mainstream employment within shipping companies.

COVID-19 response interventions coming from national governments have also varied from country to country. In Africa, several approaches to providing relief to the citizenry, particularly among West African nations, have been adopted, along with their strategies for combating the pandemic. Financial relief was provided in countries like Ghana, which included waiving three months of electricity and water bills for all citizens. Essential frontline healthcare workers were also given a daily COVID-19 allowance of GHS 150 (approximately US$26) commencing in April 2020 [46]. For seafarers whose training documentation is up for renewal every 2 and 5 years, respectively, the priority of any intervention is expected in terms of cost reductions to SCTW training and certifications. Therefore, respondents were asked about the cost of STCW documentation before the pandemic. 61.97 per cent indicated, to varying degrees, their dissatisfaction with the cost of their training and certification, whereas 29.51 per cent, to varying degrees, indicated they were satisfied with the current cost. However, 72.12 per cent indicated various degrees of dissatisfaction with the cost of the STCW certification and training during the pandemic. They indicated that the depreciation of the local currency made the cost too expensive for the already difficult times they were having. Only 16.07 per cent were satisfied to various degrees, and 11.80 per cent indicated they were neither satisfied nor dissatisfied.

Sixty-four per cent of the respondents also indicated that they had various STCW mandatory documentation that was due for expiration and required renewal. In contrast, 36 per cent indicated that they do not have any pending renewals. Of these, 60.86 per cent indicated they would need some form of financial intervention to aid in the renewal of their documents, 21.05 per cent were, however, unsure. In comparison, 18.42 per cent indicated they needed no support of that form. The latter were some of the individuals who were still engaged onboard at the time of the survey.

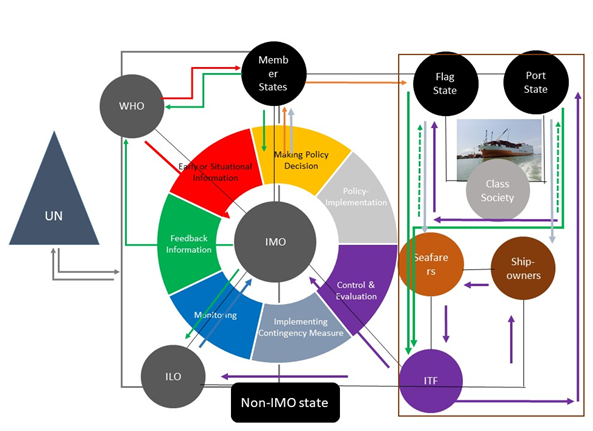

4.2 An Integrated Policy for assuring the supply chain Sustenance

Researchers view the ad-hoc nature of the various interventions implemented over time as having no demonstrable positive impact. The chaotic consequences of the observed interventions led to grave frustrations throughout the raging pandemic, as both IMO members and non-members were slow to implement measures aimed at bringing relief to the seafaring communities. Therefore, an integrated model approach, ideally with concerted effort, should lead to the production of a pandemic-level disaster measure document capable of providing an orderly flow of uniform information, leading to policy decisions, implementation, control, and evaluation across member states. Where necessary, contingency measures will be implemented while maintaining continuous monitoring, as the activities of various stakeholders are interlinked. This is schematically illustrated. In Fig. 16 below. Institutions referred to include the UN, WHO, IMO, ILO, and ITF.

Figure 16: Schematic Flow for an integrate approach towards handling extreme global even on the Maritime Industry

5. Conclusion

The plight of the ordinary seafarers who form part of minority groups such as women or those from Africa, today, will continue to linger if the appropriate national authorities are not versed with the mandate to regulate training, certification, and the general welfare of seafarers in terms of recruitment scams, extortions, and sexual harassment exploitation.

Since the onset of the pandemic, there has been economic depreciation of currencies in Africa, coupled with massive unemployment across all sectors and trade. Unfortunately, unlike their counterparts within the maritime authorities and other agencies in the marine industry, the ordinary seafarer’s documentation serving as evidence of training has validity date limits, after which, if not renewed, one can rapidly become unemployed. This process is riddled with high costs for many minorities. Extensions for the renewal dates were subsequently granted by maritime administrations, as per a UN resolution, in line with the COVID-19 crisis.

While the impact of renewal extension for seafarers of nations dominating the industry was lessened by rapid recruitment and employment, the renewal extension did not benefit the majority of the minority seafaring community, who were homebound. These individuals had no source of income support since the pandemic and could only observe their document validity dates expire, with no hope for funds to renew their documents.

As recounted by some of the respondents, the desperation of making a living has placed them in harm’s way; they have become subjects of human trafficking fraud, recruitment scams, extortion, and sexual exploitation.

Since the COVID-19 global pandemic in March 2020, as many as 1 in 6 of the 1 million crew members onboard various cargo vessels (numbering up to 60,000) at sea have been marooned [47,14]. This data, however, reflects a shortfall of the many specialised vessels with large crew sizes that operated at varying remote locations offshore before travel restrictions took effect globally. These offshore vessels encompass a range of sizes, capacities, and capabilities. Classified as ‘passenger’ vessels under the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) 1974 convention requirement, some could accommodate as many as three hundred (300) project crew in addition to the number of the ship’s marine crew under the flag of registry’s Minimum Safe Manning.4 Certificate of carriage. Indeed, the first three to six months of the declaration of a pandemic led to global chaos for the maritime industry and vessel crews. There were also economic, health, and social fallouts leading to a slew of issues such as a perpetual extension of employment agreements, job abandonment, salary cuts, suicidal cases, lack of access to medical care, mental illness, depression, and fatigue. Others included the high cost of doing business, the collapse of companies, delays and suspension in business executions in the maritime industry [1,14,16,48].

Therefore, as we begin to see concerted efforts prioritising the Covid-19 vaccinations of seafarers and marine professionals (who interface at the port of entry) from a dozen nations in reaction to the designation as ‘Key Workers’, about such direct efforts taken by the leaderships of Singapore, the nation of Malta, and Directorate General (DG) Shipping-Mumbai in the year 2021, researchers contend these minor steps are in the right direction, however, iterate the failure of the world not to have considered an integrated approach during the early stages of the pandemic as this might have left a gap in response for the failure of whose ramifications may last into the next generation if not properly addressed. It is clear that every stakeholder today feels a sense of duty to act, and therefore, several proposals in response to the pandemic have led to efforts so far. One worthy example is the resolution towards the global seafarers' vaccination program proposed by the Cyprus Shipping Deputy Ministry (SDM), which was officially adopted by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) at the Fourth Meeting of the Special Tripartite Committee of the Maritime Labour Convention, MLC 2006 – Part I. The Resolution thus calls for a mapping exercise to identify the number of vaccines needed for seafarers ashore in many ‘seafarer supplying’ countries [49].

Despite the need for further research studies in the areas of health emergencies, maritime transport, and operations, the researchers have identified several crucial recommendations to ensure progress against future emergencies. These are presented in subsequent sections.

5.1 An Integrated Policy for assuring the supply chain Sustenance

The following recommendations are worth considering by the IMO, national flag and port states, shipowners and vessel operational managers, and national maritime authorities and governments.

5.1.1 Recommendations to the IMO

The IMO, by far, has been the most responsive organisation during this crisis. There were, however, lapses observed during the global response along the journey. It does suggest that there were no contingency plans in place for dealing with global-scale destructive events. And if there were such plans, they appear to have been flawed as the Covid-19 pandemic has exposed. Therefore, most measures have been reactionary rather than proactive, given the limited level of information and expertise available to the institution. One could easily ascribe the poor flow of information reaching the IMO from sister organisations. The culprit for this is the extensive bureaucratic processes. Reacting to a global pandemic has revealed that timing and proper coordination among essential institutions are crucial for achieving results. From now on, seafarers expect pragmatism from their representative bodies, which the IMO leads.

Once again, it is time for the IMO to lead the call for inclusiveness by establishing the necessary legal foundations for such an effort. Such an effort will help in the fight against racism, violence against women and help end or minimise hostility against women onboard vessels. The effort today has been to increase the number of women in maritime education. However, this has not translated significantly into jobs for women, nor for other minority groups, such as those of African origin.

Due to the chaotic nature of the pandemic in its early stages, numerous irregularities appear to have occurred, especially in the seafarers' employment sector. Although under the auspices of the ILO, the MLC 2006 provides seafarers with substantial support from the ITF (International Transport Federation), which the IMO aids. However, seafarers from minority groups suggest they received no benefits when being laid off or made redundant after serving various companies. The suggested organisations of concern introduce a regulatory policy concerning situations of this nature and ensure strict adherence to it.

5.2 Recommendations to Coastal (Port) States and Flag State (Port of Registry)

The speed of reaction observed during the pandemic has been revealing. While some national flags and port states reacted swiftly to implement measures to aid seafarers during the crisis, others appeared slow and somewhat exploitative. Even as COVID-19 testing, manufacturing, and availability gained worldwide coverage, with test results tunable under 48 hours, these nations maintained a 14-day travel quarantine period before testing.

Given that both flag and port state countries cannot ignore their obligation to their maritime economies, for which the seafaring community remains the backbone, greater efforts at ensuring seafarers and naval professionals are given covid-19 vaccination priority to safeguard the world economy remains fluid –noting that given the extensive network of interactions existing within the maritime industry from marine insurers to bankers, commodity producers to consumers, ship owners to charterers, shipbrokers to surveyors, recruitment agencies to trained seafarers, hotels to flight attendants, among others, actions taking in one country along each step under this ‘blind’ processes have a direct and indirect consequence on the other in another step or multiple steps within the same nation or another nation.

There is also the need for port state and flag states to re-examine their responsibilities under the UNCLOS (United Nations Convention of Law of the Seas) 1982 Article 24, 94, 98 clauses 2, and article 218, and any social responsibilities under humanitarian grounds per the various UN charters as over and over again, reports suggest port and flag states authorities refused to provide humanitarian support to distress crew amid the pandemic.

The need to expressly state an obligation within UNCLOS 82, by amendment, to guide the conduct of a flag or port state in distress vessels calling out for help is long overdue. The resistance is a witness to the refugee crises in the Mediterranean Sea from the Middle East, and again during the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic, with distressed vessels. Therefore, being proactive in implementing resolutions with care and tact is required at all times.

5.2 Recommendations to Coastal (Port) States and Flag State (Port of Registry)

Ship-owners and vessel managers remain an integral part of the global maritime industry. However, they prefer to focus on making a profit, cutting excess costs and losses, rather than advising on and advancing policies. The era spared by the pandemic, however, has shown significant flaws in the world seafaring recruitment schemes and support for training institutions that have, over the years, largely been discriminatory against Africans. While it is taking a while for international institutions to take advantage of Africa’s growingly youthful and literate population and thereby entrusting the African seafarer with the significant responsibilities of manning multi-dollar marine assets, companies like the Bernard Shultz Management group (BSM), have taken a noteworthy step at enhancing inclusiveness with setting up officially in Africa with Ghana hosting its headquarters. The acknowledgement of this effort, however, is not an endorsement of the brand, but rather a statement of fact in the company's policy decision-making by a ship management company.

Since the events of 2020 continue to drive the agenda of the present times, it is, therefore, time for the minority groups within the maritime sector to be given an opportunity through a quota system for Africans and women. Such an effort towards inclusiveness provides a better foundation for the world as a whole in preparation for foreseeable circumstances, such as the current pandemic.

5.4 Recommendations to Governments and National Maritime Authorities

With guidance from IMO members from developing countries, they could consider subsidising the STCW certification and training while COVID-19 lasted. There is also the option of instituting a fund pool that could be relied upon by the registered seafaring community for their renewal, with repayment terms.

Acknowledgements

Our most sincere acknowledgement goes to our family and friends who supported us throughout this study in various ways. We want to thank the surveyors who contributed to this study with their extensive experience and thoughtful insights. Our final, but not least, thanks go to Dr D. Y. Patil Vidyapeeth, Pune (Deemed to Be University), and the institutional affiliates of the expert surveyors for making this study a success.

Competing Interests:

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

Sackey, A.D., Tchouangeup, B., Lamptey, B.L. et al., (2021). Outlining the challenges of Covid-19 health crises in Africa’s maritime industry: the case of maritime operations in marine warranty surveying practice. Maritime Studies. 20, 207-223. View

UNCTAD, Review of Maritime Transport 2019. (2020) View

Oxford Business Group, The impact of Covid-19 on global supply chains. (2020). https://oxfordbusinessgroup.com/news/ impact-covid-19-global-supply-chainsView

BIMCO, MANPOWER REPORT: The global supply and demand for seafarers in 2015. (2015). https://www.ics-shipping. org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/manpower-report-2015 executive-summary.pdf View

Sackey, A.D., Lomotey, B., Sackey, A.D., et al. (2022). Delineating the relationship between maritime insecurity and the COVID-19 pandemic on West African naval trade. J. Shipp. trd. 7, 20. View

Caesar, L.D., Cahoon, S. & Fei, J (2015). Exploring the range of retention issues for seafarers in global shipping: opportunities for further research. WMU J Marit Affairs 14, 141–157. View

The Nautilus International (2020). The Coronavirus Impact on Seafarers Could Lead to Large Numbers Quitting the Industry. View

Marcus Hand (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on the attraction of a seafaring career. View

Raunek (2021). 12 Main Reasons Seafarers Quit Sea Jobs. View

Sackey, A.D., Sackey, A.D., Segbefia J. E., et al. (2021a). Tackling The Impact Of Maritime Insecurity Within The Gulf Of Guinea Along With Promising Expansion Of Trade In Coastal West Africa, World of Shipping Portugal International Research Conference on Maritime Affairs

JILLIAN SMITH (2021). Multiple cruise ships denied entry to foreign ports due to COVID cases, https://komonews.com/ news/nation-world/multiple-cruise-ships-denied-entry-to foreign-ports-due-to-covid-cases View

MyGard (2022). Handling of COVID-19 positive crew cases in China. View

International Seafarers' Welfare and Assistance Network, ISWAN (2020). More States join the IMO call to designate seafarers as key workers. https://www.seafarerswelfare.org/ news/2020/more-states-join-imo-call-to-designate-seafarers-as key-workers View

Deniece M. Aiken (2021). The Law: A new era for maritime governance – Inter-connectivity and coordination in a post COVID-19 world. Nunes Scholefield Deleon & Co. Kingston, Jamaica

International Seafarers' Welfare and Assistance Network, ISWAN, (2021). The shipping industry demands vaccine priority for seafarers amid renewed struggles with crew changes. View

Radic A., Lück M., Ariza-Montes A., and Han H. (2020). Fear and Trembling of Cruise Ship Employees: Psychological Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. View

Safety4sea2020 (2021). Shipping demands vaccine priority for seafarers amid crew change crisis. View

International Maritime Organisation (IMO) (2020). International Convention on Standards of Training, Certification and Watchkeeping for Seafarers (STCW). View

Barthélemy Blédé, (2015). Tomorrow is International Day of the Seafarer, an opportune time for Gulf of Guinea states to review the shortfalls in their maritime transport systems. View

Sackey A.D. and Lamptey B.L. (2019). Activities of Local Fishermen within Ghana’s Offshore Construction Fields, Impact on Operations- Polar Onyx Experience. Regional Maritime University Journal Vol. 6 (85-102), Accra, Ghana View

UNCTAD (2022). UNCTAD’s Review of Maritime Transport 2022: Facts and Figures on Africa. UNCTAD/ PRESS/IN/2022/002. https://unctad.org/press-material/ unctads-review-maritime-transport-2022-facts-and-figures africa#:~:text=Trends%20in%20maritime%20trade,5%25%20 of%20total%20goods%20discharged. View

International Labour Organisation, ILO (2020). Report on employment in Africa (Re-Africa), Tackling the youth employment challenge. View

The Eastern African Standard (2002). Kenya: Highlights of Cruise Jobs Scam. View

GM Events (2021). An Overview: Gulf of Guinea piracy in 2021. (IMDEC) International Maritime Defence Exhibition & Conference. View

Sackey AD, Sackey AD, Segbefia JE, Lee RO, Lamptey BL, Chantiwuni M, Teye AA, Danquah BK, Afful P. (2023). A review: Tackling the Impact of Maritime Insecurity Within the Gulf of Guinea Along With Promising Expansion of Trade in Coastal West Africa. Gulf Spectrum Journal, pp 31-43

RMU (Regional Maritime University) (2021). Our History. View