Journal of Social Work and Welfare Policy Volume 3 (2025), Article ID: JSWWP-155

https://doi.org/10.33790/jswwp1100155Research Article

Improving Responses to Mental Health Crises: An Analysis of State Legislative Approaches

Steven Keener* and Kaylee Moore

Department of Sociology, Social Work and Anthropology, Christopher Newport University, 1 Avenue of the Arts, Newport News, Virginia 23606, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Steven Keener, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Criminology, Department of Sociology, Social Work and Anthropology, Christopher Newport University, 1 Avenue of the Arts, Newport News, Virginia 23606, United States.

Received date: 05th June, 2025

Accepted date: 30th July, 2025

Published date: 01st August, 2025

Citation: Keener, S., & Moore, K., (2025). Improving Responses to Mental Health Crises: An Analysis of State Legislative Approaches. J Soci Work Welf Policy, 3(2): 155.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

When law enforcement responds to individuals in a mental health crisis, the risk of danger is higher than traditional police responses. Many U.S. localities have begun mandating improved training for officers, creating co-responder teams where officers work with mental and behavioral health professionals, and/or implementing mobile crisis teams staffed with social workers and other mental and behavioral health professionals. State legislatures and governors can mandate and/or facilitate the implementation of improved response models to mental health crises in the community. In this project, state-level efforts to facilitate improved local response models to individuals in crisis were analyzed. Specifically, legislation that each state has passed regarding mental health crisis response was researched and analyzed to determine their ability to produce procedural just outcomes. The results indicate that state legislation fit within six categories, ranging from mandates to implement local response teams to the creation of commissions that produce guidelines and best practices. The legislative approaches have the potential to improve perceptions of procedural justice, which can facilitate safer interactions in the short-term and long-term. The implications and limitations of the analysis and its results are explored.

Keywords: Mental Health, Crisis Response, Co-responder Teams, Procedural Justice

Introduction

Law enforcement responses to mental health crises are a growing concern. When police respond to an individual with serious mental illness (SMI), it is 11.6 times more likely that the interaction turns dangerous [1]. Many individuals with a mental illness that were killed by police were killed at home and were not brandishing a weapon when the officer responded [2]. However, individuals with mental illness only make up a small portion of violent offenders and are more likely to be a victim of violence than a perpetrator of it [3,4]. There is growing awareness that traditional police-led responses are often inadequate for addressing mental health needs, and systemic change is necessary to promote safer outcomes for all parties involved [5,6]. Several innovative strategies to minimize these interactions have emerged. One such strategy involves crisis response teams that employ professionals such as social workers, nurses, and psychiatrists [7]. The aim is that these teams will respond to crises in a safer manner, when compared to officer-only responses, due to their expertise and experience working with mental illness and connecting individuals to community-based resources [8].

Improving response mechanisms to mental health crises is a common part of sequential intercept models in localities, such as towns, cities, and/or counties. Sequential intercept models identify criminal justice process decision points to determine how interventions can happen at those points to prevent individuals with mental health issues from being further processed into the justice system [9]. The first intercepts are points of early intervention focused upon how criminal justice, mental health, and substance use stakeholders can divert individuals away from the criminal justice system before arrest [10]. This local approach to diversion is common because the U.S. criminal justice system is decentralized and largely local and state controlled [11]. State legislation is a major driver of local criminal justice change, and it can also be a driver of localities implementing inter-disciplinary response teams at these early points of intercept [12,13].

This study aims to analyze state-level efforts to facilitate improved local responses to mental health crises. In this project, the existing literature on responses to mental health crises was reviewed. This included a focus on the efficacy of these models, as well as how they impact perceptions of procedural justice. Research was then conducted on state legislative efforts to facilitate non-law enforcement, or improved law enforcement, responses to mental health crises. These approaches were analyzed to determine what similar and different approaches each state had taken. After these approaches were sorted into thematic categories based on their similarities, they were analyzed to determine how they align with a procedural justice theoretical framework and the existing empirical literature.

Literature Review

The existing literature details mental health crisis response models and their impact. This includes training for law enforcement, as well as co-responder teams and mobile crises teams. The literature review first explains procedural justice theory and how it can be applied to mental health crisis response. It then details the existing literature on response models to mental health crises. It concludes with a focus on the role of state legislation in shaping local criminal justice efforts.

Procedural Justice Theory

Procedural justice theory argues that the way people react to legal authorities, such as law enforcement, is based upon whether they view the system and its actors as fair and just. Individuals are more likely to cooperate with law enforcement commands if they believe the officers use fair procedures when interacting with the public [14,15]. Watson and Angell [16] argue that this theoretical framework can help us better understand how law enforcement responses to individuals with mental illness can impact whether individuals cooperate with officers. While many training programs focus on improving officers’ knowledge of mental illness, this framework points toward training focused upon officer behaviors, such as treating individuals with dignity, allowing them a voice in the conversation, and expressing concern for their situation. This can improve officer responses and build trust [17]. Crisis intervention teams, as well as crisis intervention trained officers, can incorporate elements of procedural justice theory [16,18]. Their approach, and the training they receive, communicate that individuals with a mental illness are respected members of the community and should be treated with respect.

Approaches guided by procedural justice can improve various outcomes and/or processes in the criminal justice system. For example, in problem-solving courts, such as mental health courts, improved perceptions of procedural justice of the judge can help improve court outcomes [19]. Baker and colleagues [20] found, in their survey of females behind bars, that those that perceived the courts as procedurally just were more likely to report they felt an obligation to obey law in the future. When perceptions of police legitimacy are higher, it is more likely individuals perceive their treatment by officers as procedurally just [21]. Within policing, when personnel view their supervisors as practicing procedurally just organizational decision-making, it can improve trust in administration, job satisfaction, and commitment [22]. Utilizing a procedural justice focus can produce an array of positive benefits within the criminal justice system. Improved responses to individuals in mental health crises can follow this procedural justice framework [16,18]. This could improve cooperation in the short-term and build trust in the system and its actors in the long-term.

Law Enforcement Approaches to Mental Health Crises

The existing literature has documented the difficulties of officers responding to individuals in crisis and the potential dangers faced by the civilian in those encounters. Officers have reported interactions with individuals with mental illness as challenging and conflictual, describing individuals’ behavior as irrational and unpredictable [23]. They have also described dedicating a large amount of time working with individuals with mental illness and struggling to know how to deal with the symptoms in general, as well as how find community support for them [24,25]. For the civilians, individuals with SMI are more likely to experience use of force in interactions with law enforcement when compared to individuals without SMI [1,26]. Individuals with a mental illness account for approximately 25% of all fatal shootings involving law enforcement [27]. Many individuals with a mental illness that were killed by law enforcement were at home and did not brandish a weapon during the incident [2]. Despite these dangers, police officers have increasingly become mental health crisis first responders [28]. However, they often lack the expertise necessary to do proper mental health work, but they are forced to respond when there is a lack of community resources or other response alternatives [29]. Police can use procedurally just responses to individuals with mental illness; however, they run into many structural and personal barriers to operating in this manner [30].

Attempts to minimize dangerous interactions have facilitated reform efforts within police departments. Internal efforts typically involve improved training on how to better identify and respond to mental health issues [31]. Crisis intervention team (CIT) training is the most widely adopted model of this nature [32]. The Memphis model CIT program involves 40 hours of training for a select group of officers, training for dispatch, and a centralized mental health facility where individuals can be taken for help [33]. In general, CIT training involves roleplay exercises and lectures, and it emphasizes the guardian mindset of officers, which can in turn enhance procedural justice [34,35]. However, localities often implement it differently, which can explain some mixed results [36]. For example, some studies have found that individuals that go through CIT training have a better understanding of how to communicate effectively with individuals in crisis, they perceive themselves as less likely to use force in these situations, and they feel more prepared to respond to calls involving SMI [37-40]. However, some studies have found a lack of evidence that CIT models reduce use of force incidents, arrests, days in jail, and injuries, and have a measurable impact on crisis outcomes [8,41-44]. In order for this approach to be successful, departments need to have good relationships with, and be connected to, community mental health services [45]. These mixed results and varied implementation approaches point to the potential benefit of exploring other approaches.

Other Responses to Crises

While improved training can provide some officer-level benefits, officer-only response models continue to place the burden of mental health response largely on law enforcement. The empirical literature raises questions about the limitations of police being involved in public health issues of this nature [46]. Co-responder teams are a response mechanism where law enforcement works collaboratively with mental health professionals. While they can vary across localities, in one version of these teams, a law enforcement officer and mental health or substance abuse professional respond jointly to a behavioral health crisis [47]. These models can mitigate the pressure on both the healthcare and justice system by sharing the response workload. Proponents of these models argue they can facilitate decreased arrests, jail admissions, and hospitalizations, and safer responses to crises [47-49]. They are particularly useful in areas that do not have the capacity to fully remove law enforcement from the response model [50].

An array of evaluations has measured the impact of these response models in comparison to traditional law enforcement only responses. In some cases, researchers have found that co-responder teams reduced the number of police detentions and psychiatric hospitalizations, and have improved client perceptions of care [51]. These working relationships between law enforcement and mental health providers can also shape officer willingness to use non-jail alternatives to solve problems [40]. Evaluations have found they can produce better outcomes than law enforcement only response models, including improved perceptions of procedural justice [52]. Co-responder teams can reduce risks of immediate arrests and involuntary commitment is used sparingly, while also saving costs [48,53-56]. They can also increase general collaboration between the mental health system, criminal justice system, and advocates, which further reduces the number of individuals with a mental illness behind bars and improves linkage to community resources [57-60]. Co-responder teams are also more likely to exercise humility and empathy, communicate in a calm manner, be nonjudgmental, operate in a trauma-informed manner, and relate to clients due to relevant lived experiences, all of which builds trust [61,62]. While there is support for positive impacts of co-responder teams, there are also studies that have produced less supportive results.

Several studies have produced mixed results of the impact of co responder models. Some studies have produced findings with little or no support for them providing better outcomes than officer-only responses to crises [8,63]. There is also a great deal of variation in the guidance, staffing, and operations of these teams, which can impact their evaluations and impact [64]. In fact, Hofer and colleagues [65] found no costs savings as a result of co-response team implementation. Every-Palmer and colleagues [54] found co response interventions had fewer emergency department admissions but did not find these teams had less use of force. There can also be issues in civilians not being aware of the co-responder team’s existence, limited hours, a lack of follow-up support, and intimidation with an officer still present [66,67]. These mixed results clearly illuminate that co-responder models are not a perfect solution for responding to mental health crises.

Some localities have implemented response models fully external to police departments. These external models are typically called mobile crisis teams (MCTs). MCTs respond without law enforcement unless it is absolutely necessary for police to be present [34]. These teams are composed of a group of trained mental and behavioral health professionals, such as social workers, nurses, and psychiatrists [7]. The adoption of MCTs exemplifies a shift toward more public health-centered approaches, particularly in areas aiming to reduce reliance on emergency departments, jails, and police as de facto mental health providers [68]. MCTs conduct on-site assessments, de-escalate situations, and connect individuals to community-based services at the time of crisis [34]. This model has been found to be a more cost-effective approach, as evidenced by a documented reduction in hospitalizations and institutionalizations in localities with these teams [51]. MCT implementation provides a promising alternative to crisis response.

State Legislation in Criminal Justice Reform

All of this research on crisis response options and impact are focused on locality-level response models within, or just outside of, the criminal justice system. The United States criminal justice system is largely decentralized [11]. State and local governments have direct power over the majority of the United States criminal legal system and crime control efforts [69]. For example, while federal legislation impacted the growth of mass incarceration in the U.S., most of it was driven by ‘tough on crime’ state legislation, such as the Rockefeller drug laws in New York [70]. On the other hand, there are numerous examples of state legislatures initiating reform efforts. For example, in 2022 Oklahoma passed legislation that reduced time served requirements for individuals on parole and probation and California passed legislation allowing individuals to petition the court if racial bias occurred in their case [13]. Mental health crisis response is an area where state legislation can be used to drive new approaches. For example, Virginia passed a law that mandated all local community service boards or behavioral health authorities implement a community care or mobile crisis team to respond to mental health crises in their community [12]. According to the Virginia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Services [71], the law was named the Marcus Alert, after Marcus-David Peters, a teacher that was killed by Richmond police in 2018 while in the midst of a mental health crisis. Thus, one method to initiate local mental health crisis response is through state legislation.

Methods

The persistent challenges of responding to mental health crises has led many localities to explore alternative approaches. Localities can implement response models, such as co-responder teams, on their own. However, as was the case in Virginia [12], state legislation can facilitate or mandate the growth of theses alternative response models. In this study, state facilitation of response models to mental health crisis was explored. State legislative approaches were then then analyzed to determine how they align with the existing empirical literature on mental health crisis response models, as well as how they align or do not align with a procedural justice theoretical framework.

To execute this study, each state legislative website was searched to determine if any bills had been passed and signed into law related to mental health crisis response. If no such bills were found in a state legislative website, searches using a general Google browser were conducted to see if there had been such a bill and it just did not show up due to incorrect search terms being used, or some other issue. In those cases, there was media coverage of such bills being proposed and/or passed. The bill number was commonly included in the article, or there was a hyperlink to the bill in the state legislative website, which allowed the access of the bill’s text. For the states that had passed such a law, the text of the final version of the bill that passed the state legislature and was signed into law by the governor was copied and pasted into a spreadsheet. For states that were considering a bill of this nature at the time of data collection but had not passed it yet, a section in the spreadsheet identified those states and the current version of the bill was included.

The states were first organized in the spreadsheet into those that had passed a mental health crisis response law, those that had not passed such a law, and those that were currently considering a bill of nature. For those states that passed legislation, the text of each bill was analyzed to determine what the law actually did, and categorical identifiers were used to label and organize each law. For example, if a state mandated that localities implement a crisis response team, this was categorized as ‘mandating local implementation of crisis response team’. For states that created grant funding that localities could apply for and use to create a response team, they were categorized as ‘incentivize local implementation of crisis response team through grant funding’. The other categories are detailed in the results section. This determined the similarities and differences in state legislative approaches. After each category was identified and each state was sorted into these categories based upon the law, or laws, they had passed, each category was analyzed using a procedural justice theoretical framework. This helped determine if these approaches could facilitate procedural just outcomes and/or increase perceptions of procedural justice when mental health crisis response occur. The categories were also analyzed to determine how they align with the existing empirical literature detailed in the literature review. The procedural justice and literature analysis is detailed in the discussion section.

Results

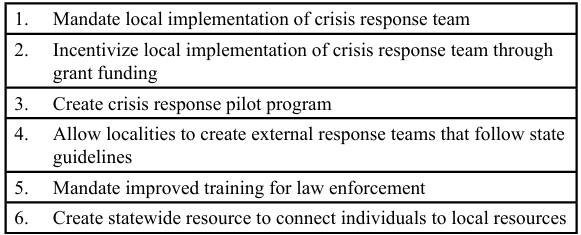

The results indicate that the legislation passed, to this point, can be sorted into six unique categories. After identifying each of these categories, they were analyzed using the procedural justice theoretical framework, and the existing empirical literature, to determine their potential impact. The results of that analysis are detailed in the discussion section. Table 1 includes each of the six categories identified. 18 states have not passed any law that fits in these categories and approximately six states were considering legislation related to mental health crisis response at the time of data collection. All of the remaining states have passed a law, or laws, that fit in these six categories. There were several states that passed laws that fit into multiple categories, so they are not mutually exclusive.

States that passed legislation fitting into category one mandated that localities implement a crisis response team. At the time of data collection, four states had implemented such a law. Virginia, for example, mandated that all community service boards and behavioral health authority areas create a Marcus alert system by July 1, 2028. A Marcus alert system is a behavioral health response for crises that can divert individuals into behavioral health services. The mobile response teams are to include one or more qualified or licensed mental health professionals, and a law enforcement officer can provide backup support but shall not be a member of the response team. Minnesota, another state that is classified in this category, passed Travis’ Law, which requires 911 dispatch centers to send mental health crisis teams to mental health crises instead of law enforcement. Both laws were named after individuals killed by law enforcement during a mental health crisis.

Several states did not go as far to mandate response teams but attempted to incentivize local implementation through state-level grant programs. Washington, one state that took this approach, created a state-level program through which localities could apply for funding to build response teams with mental health professionals. Colorado, another state that took this approach, created a peace officer mental health support grant program that provided grants to localities to help them engage with mental health professionals. This appeared to be an intention to grow implementation of such teams without imposing a mandate, or especially an unfunded mandate.

In the third category, states passed laws that created pilot programs for mental health response teams. Illinois, one state that took this approach, created a co-responder pilot program that authorized police officers to bring social workers and mental health professionals on calls with them to help assess them and make decisions about individuals in a crisis. If successful, these pilot programs could serve as a model for other localities to replicate; however, that was not explicitly stated in the bills’ text.

In the fourth category, states passed legislation that allowed localities to utilize crisis response teams as long as they followed state guidelines and/or created commissions to create recommendations and standards. For example, Oregon passed a law that allowed mobile crisis response teams to exist as long as they followed state standards. Cities were also permitted to use county funding for these teams. Vermont created a Mental Health Crisis Commission to review law enforcement interactions with individuals in crisis, educate individuals on intervention and prevention strategies, and recommend policies, practices, and training strategies to increase successful interactions with individuals in a mental health crisis. These commissions create the guidelines and standards that the teams will eventually follow and/or be evaluated upon.

The fifth category was a common approach, in which states mandated improved training. This training focused upon improved understanding of mental health for professionals, especially law enforcement, that may respond to a mental health crisis. For example, Connecticut required the Police Officer Standards and Training Council to consult with advocates of individuals with mental or physical disabilities to develop a training curriculum for police officers on interactions with mental or physical disabilities. It also required the training curriculum to include crisis intervention strategies. Arkansas required law enforcement officers to complete at least 16 hours of training related to crisis intervention of behavioral health issues. Some states only passed legislation of this nature and did not pass legislation that fit into the other categories. Other states passed legislation mandating improved training, while also passing laws that fit into other categories.

In the last category, states passed laws that mandated improved crisis response resources at the state level but did not mandate local initiatives. For example, Indiana required the Division of Mental Health and Addiction to create a help line for emotional support and referrals to resources. Georgia created a partnership between behavioral health professionals and law enforcement so they could work as a team, but they did not mandate local implementation of response teams. This represented a state-level investment in mental health resources.

Discussion

There appears to be a divide between state legislatures that decided to mandate crisis response teams as opposed to those that decided to pilot test or incentivize them. In states like Virginia and New Jersey, these mandate laws were driven by crisis situations in which individuals were killed by law enforcement. The general assumption is that states that mandate implementation of these teams will have fewer dangerous interactions between law enforcement and individuals in crisis, as well as decreased arrests and jailings, and fewer hospitalizations [47-49,51-56]. However, evaluations of these response models have produced mixed results [8,63,65]. Also, these teams require funding, and given recent cuts to essential programs like Medicaid, this could be difficult to access. This could also strain rural jurisdictions that must cover large geographic footprints and underserved localities that do not have a wealth of resources and/or qualified professionals to dedicate to a response team. Incentivizing jurisdictions to implement a team through state-level grant funding makes sense as a way to bring most localities onboard without setting up a potential unfunded mandate. However, once again, it cannot be assumed this would automatically produce improved results given the mixed results in prior evaluations [8,63,65]. Pilot test locations can make sense because data can be tracked on their impact, and they can potentially serve as a proof of concept for other localities to replicate if they are producing positive outcomes. They can also inform other localities about the challenges they faced and ways to overcome them.

Some state legislatures see value in creating a statewide resource and/or commission or mandating improved training. Statewide resources, such as a crisis call line, can help people in need whether their locality has a crisis response team in place or not. Guidelines and recommendations created by statewide commission can help local response teams as they are being created and/or updating their policies and practices. This is especially the case when the guidelines follow best practices that emerge from the empirical literature and can help given the variance that currently exists for the guidance, staffing, and operation of crisis response teams [64]. In fact, it would be expected that localities that implement crisis response teams on their own would look for guidelines from state leaders to assure they are following best practices. Improved training for officers could help individuals in need of mental health help be referred to services and linked to care in the community. However, it is not guaranteed this training would lead to a decrease in arrests, injuries, days in jail, and use-of-force incidents [41-44,63,65,8]. These categorical approaches allow for states to engage in multiple initiatives, such as mandating improved officer training and creating a statewide commission, without mandating that localities implement response teams.

The creation of local crisis response teams can align with tenants of the procedural justice thersitical framework. However, the mixed results in prior evaluations of crisis response teams must be considered before automatically assuming they will create better and more procedurally just outcomes [8,63,65]. Despite these mixed evaluations, crisis response teams have the potential to improve perceptions of procedural justice when compared to officer-only responses [52]. This could occur because individuals in crisis situations feel they are being heard and treated fairly by professionals that understand the nuances of mental health and how to approach and de-escalate crisis situations. This is not out of the realm of possibility when considering the literature that describes response teams as likely to exercise humility and empathy, communicate in a calm manner, be nonjudgmental, operate in a trauma-informed manner, and relate to clients [61,62]. Perceptions of fair treatment and procedural justice could also be improved if individuals in need of mental health services are being referred and/or directly connected to community-based resources. This is also not out of the realm of possibility when considering the literature on how these teams can increase collaboration between the mental health and criminal justice system [57-60]. While these response teams can increase perceptions of procedural justice, they are not the only mechanism for doing this.

A legislative approach focused on improved training and state guidelines can also align with a procedural justice theoretical framework. For example, if better trained officers give more space to listen to individuals in crisis and work to connect them to community resources and avoid arrest and incarceration, this could improve perceptions of procedural justice. This is possible when considering that some existing literature documented CIT-trained officers have a better understanding of how to communicate effectively with individuals in crisis and perceive themselves as less likely to use force in these situations [37,38,40]. However, some evaluations have found that CIT models do not always produce fewer arrests and injuries, as well as less incarceration [8,41-44]. State guidelines can help here, especially in regard to standardizing training and response model, since localities often implement CIT differently [36]. If departments doing this training also focus on creating and maintaining good relationships with community mental health services, this can increase referrals and align with a procedurally just approach [45]. All of these approaches have the potential to align with the procedural justice framework, but the manner in which they are implemented and executed matter.

This analysis gives an overview of how state legislators are approaching local response models to mental health crises. However, there are a number of limitations to consider. In general, searching for state-level legislation can be complicated and some applicable legislation may have been missed, especially if different terminology was used. There can also be a disconnect between policy and practice. States may have passed laws that appear to facilitate crisis response teams but in practice, some localities may be implementing them in a manner that looks similar to the traditional law enforcement only approach. It was also apparent in the searches that in states where there was no statewide mandate or incentives, many localities had implemented crisis response teams on their own.

Conclusion

When law enforcement responds to individuals in a mental health crisis, it is more dangerous than traditional officer responses [1]. Crisis response teams that include professionals trained to identify and appropriately respond to individuals in crisis, such as social workers and behavioral health specialists, can improve perceived procedural justice of those served. Better trained officers can also increase perceptions of procedural justice when responding to individuals in crisis. This is especially the case when individuals in crisis feel like they are being heard and treated fairly by the response teams and/or trained officers [17]. However, mixed results of the impact of the crisis response teams and CIT trained officers show this outcome is not guaranteed [8,41-44,63-65]. Given the rate of individuals with SMI, who have a higher incarceration rate than the general population, in the justice system [72], there must be a continued focus on how to facilitate safer and more procedurally just outcomes for these individuals. State-level legislation can mandate or incentivize localities to implement improved crisis response mechanisms. In this analysis, it was found that state legislation of this nature can be sorted into six categories. These range from legislation mandating or incentivizing implementation of these teams to improved law enforcement training. Future researchers should focus on which of these state legislative approaches has the most positive outcomes in terms of creating safer and more just interactions with individuals in crisis.

Competing Interests:

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

Laniyonu, A. & Goff, P. A. (2021). Measuring disparities in police use of force and injury among persons with serious mental illness. BMC Psychiatry, 21. View

Saleh, A. Z., Appelbaum, P. S., Liu, X., Stroup, T. S., & Wall, M. (2018). Deaths of people with mental illness during interactions with law enforcement. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 58: 110-116. View

Thornicroft, G. (2020). People with severe mental illness as the perpetrators and victims of violence: Time for a new public health approach. The Lancet Public Health, 5(2). View

Watson, A. C., Hanrahan, P., Luchins, D., & Lurigio, A. (2001). Mental health courts and the complex issue of mentally ill offenders. Psychiatric Services, 52(4): 477-481. View

Balfour, M. E., Stephenson, A. H., Delany-Brumsey, A., Winsky, J., & Goldman, M. L. (2021). Cops, clinicians, or both? Collaborative approaches to responding to behavioral health emergencies. Psychiatric Services, 73(6). View

Watson, A. C., Morabito, M. S., Draine, J., & Ottati, V. (2008). Improving police response to persons with mental illness: A multi-level conceptualization of CIT. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 31(4): 359-368. View

The Council of State Governments Justice Center. (2021). How to successfully implement a mobile crisis team (field notes). View

Marcus, N. & Stergiopoulos, V. (2022). Re-examining mental health crisis intervention: A rapid review comparing outcomes across police, co-responder and non-police models. Health & Social Care in the Community, 30(5): 1665-1679. View

Willison, J. B., McCoy, E. F., Vasquez-Noriega, C., Reginal, T., & Parker, T. (2018). Using the sequential intercept model to guide local reform. Urban Institute. View

Abreu, D., Parker, T. W., Noether, C. D., Steadman, H. J., & Case, B. (2017). Revising the paradigm for jail diversion for people with mental and substance use disorders: Intercept 0. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 35(5-6): 380-395. View

Ponomarenko, M. (2024). Some realism about criminal justice localism. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 173(789): 789-867. View

HB 5043, 2020 Special Session. (2020). View

Porter, N. D. (2022). Top trends in criminal justice reform, 2022. The Sentencing Project. View

Cullen, F. T. & Wilcox, P. (2010). Tyler, Tom R.: Sanctions and procedural justice theory. In F. T. Cullen, P. Wilcox (Eds.) Encyclopedia of Criminological Theory (Vol. 2, pp. 973-975). SAGE Publications, Inc. View

Sunshine J. & Tyler, T. R. (2003). The role of procedural justice and legitimacy in shaping public support for policing. Law & Society Review, 37(3): 513-548. View

Watson, A. C. & Angell, B. (2017). Applying procedural justice theory to law enforcement’s response to persons with mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 58(6). View

O’Brien, T. C. & Tyler. T. R. (2019). Rebuilding trust between police & communities through procedural justice and reconciliation. (2019). Behavioral Science Policy, 5(1): 35-50. View

Jones, A. M., Vaughan, A. D., Roche, S. P., & Hewitt, A. N. (2022). Policing persons in behavioral crises: An experimental test of bystander perceptions of procedural justice. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 18: 581-605. View

Dollar, C. B., Ray, B., Hudson. M. K., & Hood, B. J. (2018). Examining changes in procedural justice and their influence on problem-solving court outcomes. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 36(1): 32-45. View

Baker, T., Pickett, J. T., Amin, D. M., Golden, K., Dhungana, K., Gertz, M., & Bedard, L. (2015). Shared race/ethnicity, court procedural justice, and self-regulating beliefs: A study of female offenders. Law & Society Review, 49(2): 433-466. View

Nagin, D. S. & Telep, C. W. (2017). Procedural justice and legal compliance. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 13: 5-28.View

Donner, C., Maskaly, J., Fridell, L., & Jennings, W. G. (2015). Policing and procedural justice: A state-of-the art review. Policing: An International Journal, 38(1): 153-172. View

Wittmann, L., Jorns-Presentati, A., & Groen, G. (2021). How do police officers experience interactions with people with mental illness? Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 36: 220 226. View

Godfredson, J. W., Thomas, S. D., Ogloff, J. R., & Luebbers, S. (2011). Police perceptions of their encounters with individuals experiencing mental illness: A Victorian survey. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 44(2): 180-195. View

Wood, J. D. & Watson, A. C. (2021). What can we expect of police in the face of deficient mental health systems? Qualitative insights from Chicago police officers. Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 28(1): 28-42.View

Rossler, M. T. & Terrill, W. (2016). Mental illness, police use of force, and citizen injury. Police Quarterly, 20(2): 189-212. View

Stout, C. (2019). How mental illness affects police shooting fatalities. International Bipolar Foundation. View

Duff, J. H., Gallagher, J. C., James, N., & Sorenson, I. (2022). Issues in law enforcement reform: Responding to mental health crises. Congressional Research Service. View

Cummins, I. (2022). ‘Defunding the police’: A consideration of the implications for the police role in mental health work. The Police Journal: Theory, Practice and Principles, 96(2). View

Morgan, M. M. (2024). “The response hasn’t been a human-to human response, but a system-to-human response”: Health care perspectives of police responses to persons with mental illness in crisis. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 39: 706 719. View

Bureau of Justice Assistance. (2019). Police-mental health collaborations: A framework for implementing effective law enforcement responses for people who have mental health needs. Justice Center: The Council of State Governments. View

Campbell, J., Ahalt, C., Hagar, R., & Arroyo, W. (2017). Building on mental health training for law enforcement: Strengthening community partnerships. International Journal of Prison Health, 13(3-4): 207-212. View

Rogers, M. S., McNiel, D. E., & Binder, R. L. (2019). Effectiveness of police crisis intervention training programs. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 47(4). View

Police Executive Research Forum. (2023). Rethinking the police response to mental health-related calls: Promising models. View

Wood, J. D. & Watson, A. C. (2016). Improving police interventions during mental health-related encounters: Past, present and future. Policing and Society, 27(3): 289-299. View

Pelfrey Jr., W. V. & Young, A. (2020). Police crisis intervention teams: Understanding implementation variations and officer level impacts. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 35: 1-12. View

Compton, M. T., Neubert, B. N. D., Broussard, B., McGriff, J. A., Morgan, R., & Oliva, J. R. (2011). Use of force preferences and perceived effectiveness of actions among crisis intervention team (CIT) police officers and non-CIT officers in an escalating psychiatric crisis involving a subject with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 37(4): 737-745. View

Morabito, M. S., Kerr, A. N., Watson, A., Draine, J., Ottati, V., & Angell, B. (2012). Crisis intervention teams and people with mental illness: Exploring the factors that influence the use of force. Crime & Delinquency, 58(1): 57-77. View

Tartaro, C., Bonnan-White, J., Mastrangelo, M. A., & Mulvihill, R. (2021). Police officers’ attitudes toward mental health and crisis intervention: Understanding preparedness to respond to community members in crisis. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 36: 579-591.View

Wells, W. & Schafer, J. A. (2006). Officer perceptions of police responses to persons with a mental illness. Policing: An International Journal, 29(4): 578-601. View

Earl, F., Cocksedge, K., Rheeder, B., Morgan, J., & Palmer, J. (2015). Neighbourhood outreach: A novel approach to liaison and diversion. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 26(5): 573-585. View

Kane, E., Evans, E., & Shokraneh, F. (2018). Effectiveness of current policing-related mental health interventions: A systematic review. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 28(2): 108-119. View

Kerr, A. N., Morabito, M., & Watson, A. C. (2010). Police encounters, mental illness, and injury: An exploratory investigation. Journal of Police Crisis Negotiations, 10(1-2): 116-132. View

Taheri, S. A. (2016). Do crisis intervention teams reduce arrests and improve officer safety? A systematic review and meta analysis. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 27(1): 76-96. View

Redgate, S., Clibbens, N., Haighton, C., Dalkin, S., Bate, A., Girling, M., McCarthy, S., Eagles, T., Gray, J., & McKinnon, I. (2025). Mechanisms to support interventions involving the police when responding to persons experiencing a mental health crisis: A realist review. Health & Social Care in the Community, 1. View

Smith, J., & Thompson, L. (2025). Re-examining mental health crisis intervention: A rapid review comparing outcomes across police, co-responder, and non-police models. Journal of Mental Health Policy.

Krider, A. & Huerter, R. (2020). Responding to individuals in behavioral health crisis via co-responder models: The roles of cities, counties, law enforcement, and providers. Policy Research, Inc. View

Donnelly, E. A., O’Connell, D. J., Stenger, M., Gavnik, A., Regalado, J., & Rell, E. (2024). Mental health co-responder programs: Assessing impacts and estimating the cost savings of diversion from hospitalization and incarceration. Police Practice and Research, 26(3): 346-360. View

Roberston, J., Fitts, M. S., Petrucci, J., McKay, D., Hubble, G., & Clough, A. R. (2020). Cairns mental health co-responder project: Essential elements and challenges to program implementation. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 29(3): 450-459. View

Watson, A. C., Ottati, V. C., Morabito, M., Draine, J., Kerr, A. N., & Angell, B. (2010). Outcomes of police contacts with persons with mental illness: the impact of CIT. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 37(4): 302–317. View

Reveruzzi, B., Pilling, S., & Hodgekins, J. (2018). A systematic review of co-responder models of police mental health 'street' triage. BMC Psychiatry, 18, 256.

Furness, T., Maguire, T., Brown, S., & McKenna, B. (2016). Perceptions of procedural justice and coercion during community-based mental health crisis: A comparison study among stand-alone police response and co-responding police and mental health clinician response. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 11(4): 400-409. View

Childs, K. K., Elligson, R. L., & Brady, C. M. (2024); Testing the impact of a law enforcement-operated co-responder program for youths: A quasi-experimental approach. Psychiatric Services, 75(12). View

Every-Palmer, S., Kim, A., Cloutman, L., & Kuehl, S. (2022). Police, ambulance and psychiatric co-response versus usual care for mental health and suicide emergency callouts: A quasi experimental study. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 57(4): 572-582. View

Morabito, M. S. & Savage, J. (2021). Examining proactive and responsive outcomes of a dedicated co-responder team. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 51(3): 1802-1817. View

Yang, S. & Lu, Y. (2024). Evaluating the effects of co-response teams in reducing subsequent hospitalization A place-based randomized controlled trial. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 18. View

Bailey, K., Lowder, E. M., Grommon, E., Rising, S., & Ray, B. R. (2021). Evaluation of a police-mental health co-response team relative to traditional police response in Indianapolis. Psychiatric Services, 73(4). View

Ghelani, A., Douglin, M., & Diebold, A. (2022). Effectiveness of Canadian police and mental health co-response crisis teams: A scoping review. Social Work in Mental Health, 21(1): 86-100. View

Shapiro, G. K., Cusi, A., Kirst, M., O’Campo, P., Nakhost, A., & Stergiopoulos, V. (2015). Co-responding police-mental health programs: A review. Administration and Policy in Mental Health Services Research, 42: 606-620. View

Steadman, H. J., Deane, M. W., Borum, R., & Morrissey, J. P. (2000). Comparing outcomes of major models of police responses to mental health emergencies. Psychiatric Services, 51(5). View

Evangelista, E., Lee, S., Gallagher, A., Peterson, V., James, J., Warren, N., Henderson, K., Keppich-Arnold, S., Cornelius, L, & Deveny, E. (2016). Crisis averted: How consumers experience a police and clinical early response (PACER) unit responding to a mental health crisis. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 25(4): 367-376. View

Watson, A. C., McNally, K., Pope, L. G., & Compton, M. T. (2025). If not police, then who? Building a new workforce for community behavioral health crisis response. Frontiers in Psychology, 16. View

Lowder, E. M., Grommon, E., Bailey, K., & Ray, B. (2024). Police-mental health co-response versus police-as-usual response to behavioral health emergencies: A pragmatic randomized effectiveness trial. Social Science & Medicine, 345. View

Uding, C. V., Moon, H. R., & Lum, C. (2025). The status of co-responders in law enforcement: Findings from a national survey of law enforcement agencies. Policing: An International Journal, 48(1): 69-97. View

Hofer, M., Lu, T., Bailey, K. et al. (2024). An economic evaluation of a police-mental health co-response program: Data from a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Journal of Experimental Criminology. View

Kuehl, S., Gordon, S., & Every-Palmer, S. (2024). ‘In safe hands’: Experiences of services users and family/support people of police, ambulance, and mental health co-response. Police Practice and Research, 25(5): 564-578. View

Stauss, K., Plassmeyer, M., & Anspach, M. (2025). “I was able to like, kind of breathe.” Baseline perspectives and lessons learned from participants of a co-response program. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work, 22(4): 499-517. View

Clayworth, J. (2023). Counselors have replaced police in hundreds of 911 responses. Axios Des Moines. View

Wessler, M. (2025). Can they do that? A primer on the powers – and limits – of the president and federal government to shape the criminal legal system. Prison Policy Initiative. View

Eisen, L. (2020). Criminal justice reform at the state level. Brennan Center for Justice. View

Virginia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Services. (n.d.). The Marcus-David Peters Act. View

Anderson, A., Esenwein, S., Spaulding, A., & Druss, B. (2015). Involvement in the criminal justice system among attendees of an urban mental health center. Health & Justice, 3(4). View