Journal of Social Work and Welfare Policy Volume 3 (2025), Article ID: JSWWP-156

https://doi.org/10.33790/jswwp1100156Research Article

Re-authoring Disenfranchised Grief Using a 6-Step Narrative Therapy: Powerful Metaphors from “White Eyes” to “True Love”

Yuk Yee Lee Karen1*, Kam Fu Lo2, Chi Keung So3, Ying Long Liu4, and Qiumei Huang5

1Faculty of Social Sciences, UOW (University of Wollongong) College Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China.

2UOW (University of Wollongong) College Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China.

3UOW (University of Wollongong) College Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China.

4Foshan Xinyi Social Work Service Center, Guangdong, China.

5Senior Social Worker, Guangdong, China.

Corresponding Author Details: Yuk Yee Lee Karen, Assistant Professor, Faculty of Social Sciences, UOW College Hong Kong, 3/F, 18 Che Kung Miu Road, Tai Wai, New Territories, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Received date: 20th June, 2025

Accepted date: 30th July, 2025

Published date: 01st August, 2025

Citation: Karen, Y. Y. L., Lo, K. F., So, C. K., Liu, Y. L., & Huang, Q., (2025). Re-authoring Disenfranchised Grief Using a 6-Step Narrative Therapy: Powerful Metaphors from “White Eyes” to “True Love”. J Soci Work Welf Policy, 3(2): 156.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Over the past four decades, marriages between Hong Kong men and Mainland Chinese women have surged, with 18,939 recorded in mid 2023, making up 44.4% of all marriages in Hong Kong (Renmin Bao, 2024). Despite this integration, Mainland Chinese women often face stereotypes that hinder their acceptance in local communities, being labeled as “gold diggers” or “passport hunters.”

Objectives: This qualitative study investigates the use of narrative therapy maps that empower immigrant wives in cultivating a preferred identity and navigating disenfranchised grief.

Methodology: Utilizing data from an action research project, this study follows four phases: (1) planning; (2) action and observation; (3) reflection and intervention; and (4) re-planning. Thematic analysis, conducted with the consent of participants, reveals how Narrative Therapy can reshape grief narratives and challenge societal stigma.

Findings: The research highlights six-step Narrative Therapy conversation maps that effectively strengthen clients' inner resources and resist negative identities. This approach empowers Chinese migrant wives to challenge stigma and promotes better grieving through narrative therapy as a fundamental human right.

Keywords: Narrative Therapy, Disenfranchised Grief, Spouse loss, Migrant identity, Hong Kong

Introduction

According to Cesur-Soysal and Arı [1], disenfranchised grief refers to a loss that is not openly acknowledged or a mourning process that is not socially recognized. Additionally, individuals can self-disenfranchise by suppressing their emotions and denying themselves the opportunity to grieve. These situations occur when the relationship with loss is not recognized by society. In these cases, some losses are stigmatized as “worthless.” According to Neimeyer and Jordan [2] adopt the concept of disenfranchised grief, linking it to a pattern of empathic failures that subtly or apparently invalidate the bereaved person, family, or community’s unique narrative of loss. This article describes the use of narrative therapy in working with a Chinese migrant widow suffering the consequences of disenfranchised grief about her deceased husband. She discovered her preferred identity through externalizing, re-authoring practices and remembering conversations her self-stigma as a “migrant wife”. Since few intervention approaches in Hong Kong focus on disenfranchised grief related to the death of a spouse, the author uses an action research project to reflect on a six-step model for providing bereavement counseling to widows experiencing disenfranchised grief.

Mass media and stigma affecting mainland immigrant wives

Over the past four decades, marriages between Hong Kong men and Mainland Chinese women have surged, with 18,939 recorded in mid-2023, accounting for 44.4% of all marriages in Hong Kong [3]. Despite this integration, Mainland Chinese women often face harmful stereotypes. Domestic violence is prevalent in these cross boundary marriages, particularly in cases involving older husbands and younger wives. One tragic incident in 2016 occurred in Shek Wai Kok Village, involving an 83-year-old husband and his 53-year- old wife, who were forced to live together during their divorce proceedings. The wife stabbed her husband multiple times before jumping from their 17th-floor apartment. Another notable case is that of 76-year-old Mr. Ho, who remarried a woman over 30 years his junior, leading to conflict with his five children from his late wife. One daughter withdrew 4.5 million HKD from their joint account, prompting accusations of financial motives against Mrs. Ho and sparking public outrage. This situation led to the formation of a "True Love Concern Group," which has gained 337K subscribers [4]. These incidents highlight serious issues of domestic violence and societal stigma surrounding Chinese migrant wives in Hong Kong. While they attract significant media attention and call for victim protection, the underlying social stigma remains a pervasive challenge.

Women from Mainland China often face stereotypes that emphasize traditional roles, hindering their acceptance in local families and communities. They are sometimes viewed as "gold diggers" or "passport hunters." Marrying a Hong Kong citizen does not guarantee legal residency or citizenship, leaving these brides vulnerable and dependent on their husbands, which can exacerbate power imbalances [5]. Postmodern thought suggests that stigma is a socially constructed labeling process. Discriminatory stereotypes, such as "welfare dependency" and "migrant wives cheating," persist in discussions of cross-boundary marriages in Hong Kong. Domestic violence reports often blame "mainland brides," while marital conflicts are frequently attributed to cultural differences [6]. However, linguistic and cultural (particularly gender) differences can also arise in cross-border couples of the same ethnicity [7]. Marriages between partners from less and more developed countries, like those involving Mainland Chinese women and Hong Kong men, often involve an exchange of resources. This dynamic can create a narrative that frames these marriages as motivated solely by financial gain. Such perceptions lead to stress, misunderstanding, discrimination, and stigma for Chinese migrant wives. As the number of cross-boundary marriages increased in the 1990s, some couples now face aging and potential separation. Older husband-younger wife marriages continue to carry social stigma and taboo in Hong Kong society.

Right to grieve

What is Disenfranchised grief

Disenfranchised grief complicates the bereavement process [8]. Even individuals experiencing profound spousal loss may find their grief must remain private [9]. According to Packman et al. [10], disenfranchised grief arises when a loss cannot be publicly acknowledged, socially sanctioned, or openly mourned [11]. Older widows and widowers facing disenfranchisement benefit from having someone to listen. Discussing the relationship's details, its meaning, challenges, and triumphs aids in processing grief, especially when others inadvertently or intentionally silence grief-focused conversations [11]. The bereaved may not receive sympathy, and healing rituals might be limited or absent [9]. Disenfranchisement can exacerbate emotions like guilt and anger [10] and lead to social isolation [12]. This raises the question of how to support older survivors in cross-boundary marriages experiencing disenfranchised grief. What interventions can reinforce their identity and empower them to resist stigmatization?

Bereavement and spousal loss

Bereavement, particularly spousal loss, presents unique challenges for older adults, often compounded by concurrent losses outside the bereavement context [13]. This type of loss is a significant risk factor for psychological distress, especially in women; however, social support and physical activity can help mitigate these effects. Supporting older adults during widowhood and fostering shifts in societal attitudes toward this experience are crucial [14]. Those who accept spousal death often seek meaning from the past to navigate the present and future [15]. Naef et al. [16] suggested that constructing a new identity and striving for independence amid disrupted routines, loneliness, health concerns, and changed relationships are key aspects of an older person's bereavement experience. Lower perceived social support is associated with greater distress, particularly for those whose practical needs are unmet [17]. These findings indicate that enhancing social support can buffer the psychological distress associated with spousal loss. While spousal bereavement is intensely distressing, it can also lead to personal growth following adversity [18]. However, few studies have focused on the cultural and gender- sensitive aspects of this issue within Chinese communities.

Why Adopt Narrative Therapy in Grief Counseling

Narrative therapy, developed in the 1970s and 1980s in Australia and New Zealand, is grounded in social constructionism [19]. This therapeutic approach emphasizes personal experience and meaning making, gaining prominence in psychotherapy [20]. A key question arises: how can narrative practice assist individuals in understanding death and grief? [21].

The Therapeutic Power of Grief Stories

Narrative therapy posits that individuals construct their lives through stories, with experiences being multi-faceted [22,23]. “Narrative” can be broadly defined as “the telling” of a series of temporal events, conveyed in any medium, particularly through language, to delineate a meaningful sequence [24]. Stories not only recount events but also convey meaning, shaping our sense of identity [21]. In this regard, stories are not merely accounts of events or experiences; they carry significance and influence people's actions and behaviors. Narratives shape our identity and provide meaning to our lives [25]. This therapeutic approach connects isolated individuals and challenges societal norms, highlighting the importance of personal narratives and the reconstruction of meaning in psychotherapy [26]. It advocates for deconstructing dominant narratives surrounding the shame experienced by marginalized groups [26]. White [23] asserts that these issues should not be solely attributed to individuals; rather, people possess a diverse array of skills, techniques, competencies, beliefs, values, and commitments that can help them navigate their challenges. Through externalizing conversations, individuals explore unique outcomes beyond problem-saturated narratives, while re- authoring conversations create space for alternative stories and possibilities [23,27,28]. Supportive practices, such as re-membering conversations and definitional ceremonies, further enhance this meaning-making process, allowing for the emergence of a preferred self-identity [26].

Making sense of the loss

A critical focus of grief therapy is seeking constructive meaning from the experience of suffering, particularly in what appears to be a meaningless loss. Rebuilding a significant world following bereavement often involves an active process of self-reorganization and adjustment to a new life narrative [29]. This reconstruction can lead to profound transformations in one’s self-narrative [30]. As individuals come to terms with their loss and discover compensatory benefits or life lessons, they often integrate the experience, adapt, and may even undergo personal growth. Finding meaning in a spouse's death can significantly enhance well-being long after the loss [17]. “The impact of loss and grief on an individual's life meaning and self identity is profound. Bereaved individuals may lose their sense of purpose and question their life roles [31]. Numerous studies support this view, including those involving older widows and widowers [32], bereaved young people [33-35], and survivors of a loved one’s violent death [36]. These studies indicate that an inability to "make sense" of the loss by incorporating it into a personal framework of meaning is linked to complicated and chronic grief symptoms. Furthermore, the “loss story” may become the “dominant storyline” of a person's life, effectively hindering the restructuring of narratives toward more hopeful perspectives [35].

In addition to this, drawing on the work of Michael White, narrative therapy seeks to be a respectful, non-blaming approach to counselling and community work that centers people as the experts in their own lives. It views problems as separate from people and assumes people have many skills, competencies, beliefs, values, commitments, and abilities that will assist them in reducing the influence of problems in their lives [28]. Through externalization conversations, unique outcomes may be found that do not conform to a person’s problem saturated story, providing space for alternative stories and life possibilities through re-authoring conversations [23,27,28]. The core concept of the “unique outcome” of narrative therapy was inspired by White and Epston, later developed as “innovative moments” by Gonçalves et al., [37]. Unique outcomes represent experiences that exist outside problem-saturated or dominant self-narratives [13]. They function as shadow voices [38], enabling individuals to break free from these narratives [37]. Such outcomes arise when a person thinks, acts, or feels differently from their problematic narrative, as illustrated by statements like, “I deserve it; I don’t want to live like that; I want to be able to enjoy life” [13]. Support through practices like remembering, outsider-witnessing, and definitional ceremonies is beneficial [23,27,28]. This journey fosters self-identity and counters reductionist individualism by emphasizing personal resistance and the identification of alternative choices through new narratives. Narrative therapy helps individuals distance themselves from cultural discourses, allowing them to discover more comfortable and empowering stories [39].

Methodology and Research Design

This study is based on an action research project supporting rural Chinese migrant women in Hong Kong. Utilizing data from an action research project, this study follows four phases: (1) planning; (2) action and observation; (3) reflection and intervention; and (4) re-planning. Thematic analysis, conducted with the consent of participants, reveals how metaphorical expressions can reshape grief narratives and challenge societal stigma. Influenced by the ethics of care epistemology [40], it emphasizes the inclusion of clients' voices in knowledge construction. Various data collection methods were employed, including life stories, case interviews, reflection notes, observations, and letters. Conducted in the New Territories, the research utilized thematic analysis to convert audio recordings into verbatim transcripts, supplemented by member checking. The primary objective is to develop narrative therapy maps that empower immigrant wives in cultivating a preferred identity and navigating disenfranchised grief.

Research Questions

1. How can intervention approaches enhance an individual's preferred identity, reinforce their inherent resources, skills, and knowledge, and serve as resistance against stigmatized identities?

2. Develop narrative therapy maps to empower immigrant wives in cultivating a preferred identity while navigating disenfranchised grief.

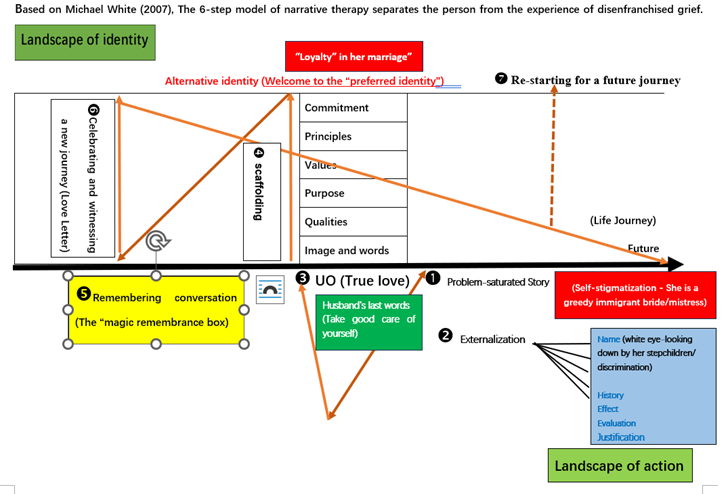

This paper utilizes information from an action research project. It demonstrates how the six-step model of narrative therapy separates individuals from problematic labels, thereby reducing stigma and discrimination. Importantly, it highlights how Mei-lin re-authored her grief, empowering her to embrace her identity as a migrant wife and cultivate the skills needed to cope with her loss. The six steps are included: 1. Externalizing the problem “White Eyes”, 2. Open dialogue with “unique outcome”, 3. Knowing the tactics of voices, 4. Welcome to the “preferred identity”, 5. Develop the “VIP” supporting alliance, 6. Celebrating a New Journey (Refer to Figure 1.).

Case background

Mei-lin and Chi-Tak married in Mainland China when she was in her 40s and he was in his 60s. Mei-lin migrated to Hong Kong following her marriage in 1997. They lived in a village house owned by Chi-Tak. Chi-Tak was diagnosed with cancer in 2005, and Mei-lin was his primary caregiver for over 20 years. Chi-Tak’s children from a previous marriage opposed Mei-lin and did not recognize her as a stepmother. In their eyes, she was simply a "mistress." She had little social support in Hong Kong since most of her family members and relatives lived in Guangzhou. Although Mei-lin and Chi-Tak enjoyed a very harmonious marriage, she had regrets about not doing more for her husband. After his death, she experienced disenfranchised grief and felt guilty for grieving. Following Chi-Tak’s funeral, his children forced Mei-lin to leave their house, although she was subsequently allowed to return. She suffered from depressive symptoms and reported going all day without eating. She expressed suicidal thoughts to a social worker. Additionally, Chinese cultural norms, such as "don't wash your dirty linen in public," were barriers that prevented Mei-lin from grieving properly.

Step 1: Externalizing the problem “White Eyes”

In Hong Kong, it is common for migrant women, particularly from Mainland China, to marry older men or serve as mistresses. Concubines hold a low status in the family and lack recognition from the husband's original family, while migrant wives are often perceived as seeking material gain rather than genuine love. This stigma led Mei-lin to feel overwhelming shame and guilt, viewing herself as a problem [41]. Most importantly, the problem-saturated story of “the immigrant wife = mistress” led to a thin description and identity conclusion of cross-boundary marriages. Externalizing conversations about one’s self-stigmatization very helpful - the person is not the problem, the problem is the problem [42] to move away from the problem. This created an opportunity to define a position about the effects of the problem in the individual’s life. The individual can gain a sense of control and power through naming the problem.

Deconstructing the social stigma

1. Externalizing the problem

Starting the counseling sessions with Mei-lin by asking her about her recent life and daily routines. I tried to enable her to release her feelings of pain and loneliness and feel free to share her story. Knowing the familiar problematic experiences is crucial in this conversation. It helped her undertake a closer review of the history and causes of her problem and its impact on her life. The problem was externalized by asking the following questions:

• Is there an image that comes to mind as you describe them?

• What do you call this?

• What name would you give to this situation?

“I named this problem 'white eyes.' There are many eyes there, and the step-son's eyes are white eyes.” (Mei-lin)

2. Tracing the history of the problem

Once the problem was named “white eyes (looking down by her step-children)”, Mei-lin could talk more about such experiences. This was a first and crucial step. Then I explored and traced the influence of the problem throughout her life.

• When did you first encounter the “white eyes”? How long ago?

• When would you say the “white eyes” was the strongest? When was it the weakest?

“When I first met his sons, “white eyes are here, they didn't call me 'step-mother,' but referred to me as 'this woman.' I felt they did not respect me. During the meal, they didn't speak at all.” (Mei-lin)

3. Exploring the effects of the problem

Tracing the “white eyes’ history” may include anything from the distant to the near past. We traced all the effects of the “white eyes” on Mei-lin’s emotional state and social life, her roles as wife and migrant, and what her hopes and dreams were.

• What is the effect of “white eyes “on your emotional state/social life?

“Being looked down upon as a 'white eye' made me feel inferior and unwilling to have any contact with my step-children and other Hongkongers." (Mei-lin)

• How did “white eyes” affect your relationship with your step children?

“So, I try my best to avoid seeing them (Chi-Tak’s son and daughters).” (Mei-lin)

• How did “white eyes” affect your energy level?

“Sometimes, I'm really afraid to see the villagers in the village because I constantly feel like they're talking about me behind my back.” (Mei-lin)

• How did “white eyes” affect how you think about yourself?

"Unable to adjust well to this place." (Mei-lin)

• How did “white eyes” affect the way you see yourself as a wife?

"Later, Chi-Tak fell ill, and his children rarely visited him. I feel like I played a role in the disintegration of Chi-Tak's family." (Mei-lin)

4. Evaluating the effects of the problem

These questions invite the individual to assess the impact of these questions and reflect on what they are learning or actually understanding. These questions give people an opportunity to assess the impact of the problem on their lives. This is a crucial step in re authoring the individual’s life story.

• Are “white eyes” a good or a bad thing?

“White eyes” made me look down on myself and unwilling to have any contacts with other Hongkongers.” (Mei-lin)

• What are your positive / or negative experiences of “white eyes”?

“White Eyes' allowed me to distinguish the sincerity of those people towards me, and also made me understand they are (son and daughters) not filial piety towards Chi-Tak.” ((Mei-lin)

5. Justification of the evaluation

These questions invite the individual to predict the specific actions they might take based on what they just talked about and what they value. These action plans will direct them towards their desired life, away from the effects of problems, and participate in the re-authoring journey.

• Using a scaling ranked 1-10 (10 maximum freedom from “the white eyes”) to show us that how much you want to be free from the “white eyes”? (social worker)

• “By staying away from the "white eyes," I give myself a score of 8, which makes me even more determined not to be underestimated by others (in my marriage). Therefore, both 9 Chi-Tak and I cherish this relationship even more.” (Mei-lin)

Mei-lin and I spent our first meeting exploring her story with her husband and how she lived with it. In our second interview, we aimed to externalize the key factors influencing her situation. Mei-lin referred to this as “white eyes” when Chi-Tak’s children forced her to leave her home following her husband’s funeral. After discussing the tactics and effects of the “white eyes,” Mei-lin was asked to evaluate those influences. She narrated:

“white eyes” made me look down on myself and unwilling to have any contacts with my step-children and other Hongkongers.

By doing so, I aimed to help Mei-lin revise her relationship with the troublesome “white eyes.” She shared the history of the “white eyes,” discovering that one tactic was labeling her as a “greedy woman” motivated by money. This led her to feel “worthless” and “isolated,” creating a negative stigma. Externalizing the problem empowered her to confront the “white eyes,” regain control, and reconnect with her true love for her deceased husband. In the third session, Mei lin revealed she had experienced suicidal thoughts about a month earlier but remembered Chi-Tak’s final words: “Take good care of yourself.” This was a unique outcome to her problem-saturated story. Most of the time in the counselling process, Mei-lin found it hard to identify these exceptions that have been forgotten “skills, knowledge, networks and resources”. A narrative therapy practitioner will claim this is “quality”, therefore the person is encouraged not to view the problem as intrinsic to themselves, thus helping them become aware of their sense-making processes and self-organizing on this problem [43].

Step 2: Open dialogue with “unique outcome”

A unique outcome may be a plan, action, feeling, statement, desire, dream, thought, belief, ability or commitment [28]. It can be an exception to a problem but can be distinguished even though the problem continues. The individual is encouraged to explore those conquered or neglected stories that are excluded from their dominant narrative [44]. White and Epston [19] refer to the exploration of these subjugated times as exploring unique outcomes [43]. Once the unique outcome is explored, it will be focused on asking questions to broaden the individual’s experiences of exceptions with the dominant story [45]. The landscape of action questions and landscape of consciousness (identity) questions help the individual explore the meanings of the behaviours and thoughts behind these unique outcomes [46].

Questions about what the individual does (landscape of action questions)

According to White [46] Landscape of action questions ask the person to map out the events, sequences, times and plots related to these unique outcomes. They help the person trace back in both the recent and distant past, preferred life events that stand in opposition to “problem-saturated” stories. The following questions helped Mei lin identify alternative plots in her life or eliminate the impact of the “white eyes” on the unique outcomes (“true love/ husband’s last words”):

• When did you feel stronger when facing the “white eyes”?

“During the New Year, Chi-Tak's family would sit down and eat together, and I feel that the "white eyes" are at their strongest.” (Mei-lin)

“The step-son said to their father, "It's your own fault.”(Mei-lin)

• When did the “white eyes” have less impact on you? Could you tell me more about what you did?

“When I would go with Chi-Tak to walk the dogs, feed the cats, and whenever I see small animals, I feel very relaxed.” (Mei-lin)

“When Chi-Tak talked to me "My wife becomes more lovely as she grows older." (Mei-lin)

Questions about what the individual does (landscape of identity questions)

The landscape of identity consists of what those involved in the action know, think, or feel, as well as what they do not know, think, or feel [47]. Through this process, a range of intentions and purposes are attributed to the actions of the protagonists and conclusions reached about their character and identity [46].

• How does the “true love/husband’s last words” (unique outcome) bring you satisfaction?

“Chi-Tak's last words were 'take good care of yourself,” I identified this as the ultimate expression of “ true love”. (Mei-lin)

At this stage, after Mei-lin identified the unique outcome as “true love”, and “her husband’s last words: ‘take good care of yourself’”, using re-authoring conversation, facilitating Mei-lin to name the unique outcome, trace its history, map and evaluate its effects and the justification of this evaluation, are crucial. The process of scaffolding includes both landscape of action questions and landscape of identity questions. It enabled her to construct a richer description of her preferred story. She identified that no longer having suicidal thoughts was because of her husband’s last words (unique outcome) and her “true love” for him. This would be a strong commitment to her husband.

Step 3: Knowing the tactics of voices

The objective of this stage was to identify the tactics of the social stigma of “Chinese migrant wife” to strengthen their skills and knowledge. The binary division between local marriages and cross- border immigrant wives is hierarchical in consideration. Knowing the tactics of voices” by using skills of discourse analysis as following:

The tactics

• The cross-border marital relationship in Hong Kong is viewed as a benefit relationship; through marrying a Hongkonger, me, the wife gains Hong Kong citizenship….no true love for her husband. (Mei-lin)

A dominant discourse of social discrimination and marginalization on cross-border immigrant wives:

• “Speaking ill of others behind their backs actually reflects a lack of respect for these women (herself).” (Mei-lin)

• “Even I feel that women like us are not qualified to truly love someone.” (Mei-lin)

Knowing the voices’ tactics enables the individual to regain “privilege”; the purpose of the voices was to render Mei-lin depressed, making her believe she was “worthless”. Deconstructing the “tactics” is perceived as resistance to the blaming from her step-children and society. Mei-lin could then gain self-appreciation that she had not treated her deceased husband badly; actually she re-discovered that she had been attentive and caring and had treated him well. Mei-lin’s journey sought out the meaningful events, that’s sparkling events or counter-plots that contradicted the dominant discourse and negative identity and became a turning point releasing her disenfranchised grief experience.

Step 4: Welcome to the “preferred identity”

Once the alternative stories were plotted and space for possibilities visualized, the scaffolding questions can help Mei-lin understand her intentions, values, beliefs and commitment to her marriage. When I asked Mei-lin what Chi-Tak’s last words (unique outcome) meant for her, her answer was evidence of her true love for her husband throughout their marriage as the source of “resistance” to the social stigma. She narrated:

• But actually, this is not the case. I stayed with Chi-Tak until the end of his life. I had true love for my husband for over a decade wholeheartedly. Stopping medical treatment was Chi Tak’s decisions.

• I was abandoned by my step-children because they did not trust or respect a step-mother who is a Chinese migrant wife. But that is not my problem.

• The relationship between Mei-lin and Chi-Tak was true love, not because of money, therefore she had the right to grieve better.

• Fighting for the right to live in the old house was not because she cared about the property. It was the best way to maintain Chi-Tak’s memory.

The meaning-making of the unique outcome helped Mei-lin develop her preferred identity from that of “greedy woman” to “true love”. This deconstruction is resistance to her step-children’s accusation that she did not treat her husband well; rather, she was attentive and caring towards him. Once the “preferred identity” germinated, Mei lin could identify the positives of her intention to live in her old house as an effective way of remembering her beloved husband and of taking good care of herself. When I asked her what her commitment to her marriage was, she responded with a Chinese proverb: “Marry a chicken and share the coop, marry a dog and share the kennel1 ”. It reflected Mei-lin’s commitment to her marriage. The preferred stories and preferred identity have been developed, and the person can see daylight.

Step 5: Develop the “VIP” supporting alliance

In this stage, the remembering conversations witness Mei-Lin’s growth, strengthen her supporting alliance and thicken her respectful identity. The concept “club of life” was first introduced by Michael White in 1997. VIP membership of this club honours those who have positive effects on our life, the “re-aggregation of members, the figures who belong to one’s life story, one’s own prior selves, as well as significant others who are part of the story” [48]. The individual can suspend or promote, revoke or privilege and downgrade specific membership in their lives. Mei-lin could regain her power and sense of control to decide who would be formally included in her life club and which club members would be afforded VIP status as evidence of their importance in witnessing her growth. In this sense, VIPs can be recognized and make a greater contribution to one’s identity construction and can be authorized to speak on such issues [47]. Therefore, this stage aimed at identifying the VIPs who had a positive effect on Mei-lin’s life. The VIPs she honored were those who walked with her in life.

Remembering conversation with the “magic remembrance box’

The remembering conversation with the “magic remembrance box’ is a metaphor created by Michael White in [42]. When an individual holds this box, the magical power will help them remember an important person in their life. The magic remembrance box helped Mei-lin remember the VIPs in her life, which helped strengthen her personal connection and remove her isolation. The questions for the remembering conversation for Mei-lin were as follows:

• Take some time to introduce this person (help Mei-lin to research the membership)

• Can you tell me a bit about him (Mei-lin had identified her husband), how you know him, what might you do with him?

• In what ways do you think you may have contributed to his life?

1. If you were to see yourself, through your husband’s eyes, what would you be pleased about in yourself?

2. Are there times you would want to tell him things?

3. Can you think of things that you have done that may reflect his influence?

4. What family value might influence how you and your husband share the connection?

What a miracle “magic remembrance box”! When Mei-lin held this box, it helped her express her sadness and unfinished business with her deceased husband. It was a gesture of releasing her isolation and disconnection from her dead loved one. Mei-lin was invited to imagine what her husband would say to her in times of hardship. She narrated:

“Mei-lin, marrying you was my greatest fortune. Take good care of yourself, I don’t want to see you cry like this. Indeed, I don’t want to see you hurt yourself. Goodbye, Àirén” (beloved-Chi-Tak).

Step 6: Celebrating a New Journey

Through the remembering conversation and its imagination, Mei lin had regained the support of her deceased husband. When her sadness was heard, her grief was healed. It is a really therapeutic means of making sense of “losses” and “connections”, which can be viewed as a critical step in grief counseling with narrative theory- Make a Wish with a Love Letter. Mei-lin wanted to write a letter (as one kind of Therapeutic document) to comfort her husband that she would drop inside the magic remembrance box. This is meaningful in Chinese culture as “In the spirit of heaven, I was covered under your blessing”:

Dear Chi-Tak

Do you remember the first day I came to Hong Kong? What was the first reaction of your sons and daughters? What was the reaction of your friends? I never forget that no one said anything during the first meal with their step-mum. …I will never forget that you took me to see the fireworks show on 1stJuly,1997 and visited Golden Bauhinia Square, Victoria Peak, and Repulse Bay. You said to me if I didn’t visit these places in Hong Kong, how could I become a Hongkonger? Do you remember that time when I met your friends? They asked you why you did not marry a younger woman? You said to them, “The older your wife, the lovelier she is”. I smiled at that time. Now, I am extremely sad about your leaving, but I understand that the cycle of life and death is natural. You’re just one step ahead of me...... a Chinese proverb - “In the spirit of heaven, I was covered under your blessing” The social worker and church friends have helped me a lot going through this hard time. Don’t worry! I will be fine. If you need anything, I hope you can tell me in my dreams.

Mei-lin

Downgrading or upgrading the Club-of-life membership

When Met-lin went through her Club-of life membership, some members may be downgraded or upgraded. She decided to delete the membership of one of her step-sons and declared that there would be no more negative impact on her life. At the end of this session, Mei-lin give her “VIP” cards to honor her husband, her old friend, church friends, the social worker, the nurse, cat feeders and the white kitten. At the final stage, Mei-lin was invited to share her recent success in fighting the “white eyes”. She said that she had accepted an old friend’s invitation to attend a women’s gathering at the church. She was trying to move forward in her life and mentioned that what impressed her most was the powerful magic remembrance box. She strongly believed that she had been loyal to her husband. She would be brave to gain the strength to live forward, even if the future turned out not to be smooth.

She narrated:

‘I retained the special label “Chinese migrate wife with loyalty”. There was nothing to be ashamed of. (Mei-lin)

Reflection and discussion

“Double listening” is the essential technique in grief narrative practice

The “double listening” of narrative therapy in this case means listening to the problem and the individual’s preferred story, the despair or hope, hate or love and vulnerability or resilience simultaneously, enabling the individual to achieve a sense of empowerment [49]. “Double listening” itself is required to satisfy curiosity and fill knowledge gaps, silences and ambiguity of discourses that provide the possibility for resistance, and doubts about the dominant discourse. Therefore, Mei-lin can be separated from her problem-saturated identity to explore her preferred identity from “greedy” to “loyalty” in her marriage. “Double listening” is the essential technique of narrative practice. As White (2003) stated, in the face of despair, dead ends, and giving up, there are always more stories, resulting in constructing a double power discourse in people lives, a double healing by redefining and reflecting the double blindness of suffering, leading to double vision of loss and gain.

Awareness of grief: cultural differences between East and West

Eastern philosophy encourages acceptance of nature. For example, Chinese culture is considered better able to endure and accept suffering than Western cultures [50]. According to The Book of Rites (Li Ki) - Three Years Mourning for Parents, the Master said: “If you can feel at ease, do it. But a superior man, during the whole period of mourning, does not enjoy pleasant food which he may eat, not derive pleasure from music which he may hear. He also does not feel at ease, if he is comfortably lodged. Therefore, he does not do what you propose. But now you feel at ease and may do it.”

From this, we can see the cultural differences in counseling direction and assessment criteria between East and West. The basic principle of grieving in western culture is “self-compassion”. In Chinese tradition, “indifference to oneself” is an effective way to better grief and gain “well-being”. I found Mei-lin was greatly affected by this life philosophy that derived from traditional Chinese culture. When I tried to counsel her in the direction of self-compassion, Mei-lin seemed incapable of taking it to heart. Therefore, I reflected that it was important for a social worker to be sensitive to diverse cultural dimensions. Hong Kong social work training and education mainly come from imported Western values and practices; indigenization of social work practice incorporating gender and cultural sensitivity is a recent phenomenon.

Co-construction the Chinese migrant wife as “welfare dependent”

Between the 1980s and 1990s, there was a rapid growth in immigration and cross-border marriages and many stories about “families of old husband and young wife” permeated the Hong Kong community. The dominant discourse continuously spread in the community was “those Chinese migrant wives just want to become Hong Kong citizens through marrying Hongkongers”. This was long debated in the community and raised concerns. The fact is that a coin has two sides. In the 1980s, labor-intensive production processes were relocated to the Pearl River Delta, small and medium sized Hong Kong enterprises moved their entire operations to China. A huge number of Hong Kong men took mistresses and second wives across the border. Some of these women are now in their 40s and 50s, and they arrived in Hong Kong after marrying a Hong Kong man in China two or three decades their senior. Undeniably, some of them were aware they were “mistresses”. But some were cheated; their residence in Hong Kong was approved via a One-Way Permit, they lived in a very small flat and their husband was getting older. They became the family breadwinner and carer; many middle-aged migrant wives work very hard, some having two or three part-time jobs simultaneously and taking up jobs that Hongkongers do not like to do. So, to some extent, they were the victims.

A study conducted in 2021by the Society for Community Organization (SoCO) [51], a pioneer of human rights in Hong Kong, estimated that only 5% of new Mainland China migrants relied on the Comprehensive Social Security Assistance (CSSA) Scheme. Such a thin description of the “welfare burden” of Chinese migration into Hong Kong creates a grand narrative that huge financial pressure was exerted on the Hong Kong Government. The social stigma of the Chinese migrant wife is not simply an individual case but also societal, historical and political. Through listening to the voice of Mei-lin, the alternative, oppositional and counter-discourses are expected to emerge in her life. The gaps, silences and ambiguity of discourses provide the possibility for resistance, for a questioning of the dominant discourse, its revision and mutation [26].

Service implications

This article describes a practical framework of grief work by using the 6-step model of narrative therapy. I found the assumptions of narrative beliefs, such as curiosity and of not knowing, allow individuals to express their problem-saturated stories at “loss” through their own cultural perspective. Therefore, it clarified the myth of cultural differences of women from Mainland China. The counseling process is more like a journey where the individual and the counselor share the dialogue of deconstruction and/or co construction, creating a liberating space for the individual to talk about guilt, disrespect, distrust and discriminatory experiences, such as the role of “second wife or concubine”, and what did it mean for Mei-lin to be a migrant wife from mainland China? Mei-lin discriminatory experience was transformed from being unheard to being heard and unspoken to spoken. Mei-lin’s suffering was not just in her heart, but in her voice. Narrative theory transformed the problematic “loss” story into a preferred story. Gradually, the individual’s preferred identity emerged. An individual’s sense of hope, knowledge, skills, values and beliefs resisted the effects of the stigma. Narrative therapy subverted the traditional role of grief counseling practice, considering social, cultural, and gender-sensitive aspects more. Mei lin ‘s story caused the author to reflect that the individual’s stories are really to be heard, especially in cross-cultural counseling. Hong Kong people are also influenced by Confucianism that affords so called respect for seniority, three- obedience and four-virtues2. Is there any bias in cross-boundary marriages? Hong Kong society was influenced by importing British and Western values, especially social work training whose core values are extremely different from Chinese culture, such as what is gender role stereotyping and how patriarchy results in women’s oppression, are men are truly liberated? It is necessary to continually question which values shape one’s life and life orientation.

Another implication of this service is the importance of the helping professional’s gender conscious raising and cultural sensitivity. Intersectionality is a concept developed by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989 to describe how different forms of oppression, such as racism and sexism, intersect and compound in people's lives [52]. This framework helps us understand how multiple forms of oppression combine to create unique challenges for individuals, aiming to address inequality more comprehensively. Intersectionality is vital for understanding the complex realities faced by marginalized groups, such as Chinese migrant wives like Mei Lin. Her situation illustrates how various forms of oppression—rooted in race, class, gender, age, living area, language and marital status—intersect to create unique challenges. As a documented immigrant with no formal education, residing in a rural area and belonging to a lower socioeconomic class, Mei Lin's experiences are shaped by multiple layers of disadvantage that are compounded by her gender. Her status as a cross-border wife, along with the stigma associated with divorce and potential remarriage, further complicates her identity. The intersectional lens reveals how these factors converge, leading to social stigma and health inequalities that are often overlooked. Recognizing these interconnected systems of discrimination is crucial in developing comprehensive strategies to combat injustice, ensuring that the specific needs and experiences of individuals like Mei Lin are adequately addressed. By acknowledging the interplay of various identities and oppressions, we can work towards more equitable solutions that truly support all marginalized groups. While there is substantial research supporting the use of narrative therapy in grief counselling in Western countries, there is limited research on its application within Chinese communities. This case serves as an important illustration, raising awareness among social work practitioners about the necessity of diverse interventions for bereaved older individuals. The study highlights the significance of creating culturally responsive and inclusive counselling environments for this population. It provides a good basis for further study into the effectiveness of narrative therapy in this context.

Competing Interests:

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

References

Cesur-Soysal, G., & Arı, E. (2024). How We Disenfranchise Grief for Self and Other: An Empirical Study. Omega: Journal of Death and Dying, 89(2), 530–549. View

Neimeyer, R. N., & Jordan, J. R. (2002). Disenfranchisement as empathic failure: Grief therapy and the co-construction of meaning. In K. Doka (Ed.), Disenfranchised grief (pp. 95-117). Research Press. View

Renmin Bao. (2024, August 28). Proportion of Marriages Between Hong Kong and Mainland China Rises to 44.4%: 16% of Young People Resist Marriage and Have Never Married. View

Mr. Ho & Mrs. Ho's True Love Attention Group. (2024). Facebook group. View

Lu, S., & Yeung, W.-J. J. (2024). The rise in cross-national marriages and the emergent inequalities in East and Southeast Asia. Sociology Compass, e13219. View

Choi, S. Y. P. (2018, 2 April). In cross-border marriage conflicts in Hong Kong, money is the heart of the matter. South China Morning Post. View

Choi, S. Y. P., & Cheung, A. K.-L. (2017). Dissimilar and disadvantaged: Age discrepancy, financial stress, and marital conflict in cross-border marriages. Journal of Family Issues, 38(18), 2521–2544. View

Rando, T. A. (1993). Treatment of complicated mourning. Research Press. View

Meyers, B. (2002). Disenfranchisement grief and the loss of an animal companion. In K. Doka (Ed.), Disenfranchised grief (pp. 251-264). Champaign, IL: Research Press. View

Packman, W., Carmack, B. J., Katz, R., Carlos, F., Field, N. P., & Landers, C. (2014). Online survey as empathic bridging for the disenfranchised grief of pet loss. OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying, 69(4), 333-356. View

Tullis, J. (2017). Death of an ex-spouse: Lessons in family communication about disenfranchised grief. Behavioral Sciences, 7(4), 16. View

Eason, F. (2019). “Forever in our hearts” online: Virtual Deathscapes maintain companion animal presence. OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying, 84(1), 212-227. View

Holm, A. L., Severinsson, E., & Berland, A. (2019). The meaning of bereavement following spousal loss: A qualitative study of the experiences of older adults. Sage Open, 9(4), 215824401989427. View

Gyasi, R. M., & Phillips, D. R. (2019). Risk of psychological distress among community-dwelling older adults experiencing spousal loss in Ghana. The Gerontologist, 60(3), 416-427. View

Chan, W. C. H. & Chan, C. L. W. (2011). Acceptance of spousal death: The factor of time in bereaved older adults’ search for meaning. Death Studies, 35(2), 147–162. View

Naef, R., Ward, R., Mahrer-Imhof, R., & Grande, G. (2013). Characteristics of the bereavement experience of older persons after spousal loss: An integrative review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 50(8), 1108-1121. View

Neimeyer, R. A. (2019). Meaning reconstruction in bereavement: Development of a research program. Death Studies, 43(2), 79 91. View

Purrington, J. (2023). Psychological Adjustment to Spousal Bereavement in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Omega, 88(1), 95–120. View

White, M., & Epston, D. (1990). Narrative means to therapeutic ends. Dulwich Centre. View

Danner, C. C., Robinson, B. B., Striepe, M. I., & Rhodes, P. F. (2007). Running from the demon: Culturally specific group therapy for depressed Hmong women in a family medicine residency clinic. Women & Therapy, 30(1-2), 151-176. View

Hedtke, L. (2014). Creating stories of hope: A narrative approach to illness, death and grief. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 35(1), 4-19. View

Freedman, J., Jill, M., & Combs, G. (1996). Narrative therapy: The social construction of preferred realities. W. W. Norton. View

White, M. K. (2007). Maps of narrative practice. W. W. Norton. View

Kerby, A. P. (1991). Narrative and the self. Indiana University Press.View

Lit, S. W. (2015). Dialectics and transformations in liminality: The use of narrative therapy groups with terminal cancer patients in Hong Kong. China Journal of Social Work, 8(2), 122-135. View

Lee, Y. Y. K., Xu, H., Liang, J., Zhan, C., & Fang, X. (2023). Transformation of women with breast cancer in Mainland China using a seven-step model of mindfulness-based narrative therapy (MBNT). China Journal of Social Work, 16(1), 59–79. View

Headman, N. (2004). In the use of narrative therapy with couples affected by anxiety disorder. Florida State University.

Morgan, A. (2000). What is narrative therapy? Dulwich Centre. View

Neimeyer, R. A. (2000). Searching for the meaning of meaning: Grief therapy and the process of reconstruction. Death Studies, 24(6), 541-558. View

Alves, D., Mendes, I., Gonçalves, M. M., & Neimeyer, R. A. (2012). Innovative moments in grief therapy: Reconstructing meaning following perinatal death. Death Studies, 36(9), 795 818. View

Rafaely, M., & Goldberg, R. M. (2020). Grief Snow Globe: A Creative Approach to Restorying Grief and Loss through Narrative Therapy. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 15(4), 482–493. View

Coleman, R. A., & Neimeyer, R. A. (2010). Measuring meaning: Searching for and making sense of spousal loss in late-life. Death Studies, 34(9), 804-834. View

Holland, J. M., Currier, J. M., & Neimeyer, R. A. (2006). Meaning reconstruction in the first two years of bereavement: The role of sense-making and benefit-finding. OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying, 53(3), 175-191. View

Holland, J. M., Currier, J. M., Coleman, R. A., & Neimeyer, R. A. (2010). The integration of stressful life experiences scale (ISLES): Development and initial validation of a new measure. International Journal of Stress Management, 17(4), 325-352. View

Neimeyer, R. A. (2006). Widowhood, grief and the quest for meaning: A narrative perspective on resilience. In D. Carr, R. M. Nesse, & C. B. Wortman (Eds.), Spousal bereavement in late life (pp. 227–252). Springer. View

Currier, J. M., Holland, J. M., Coleman, R. A., & Neimeyer, R. A. (2007). Bereavement following violent death: An assault on life and meaning. In R. Stevenson & G. Cox (Eds.), Perspectives on violence and violent death (pp. 175–200). Baywood. View

Gonçalves, M. M., Matos, M., & Santos, A. (2009). Narrative therapy and the nature of “innovative moments” in the construction of change. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 22(1), 1-23. View

Gustafson, J. P. (1992). Self-delight in a harsh world, Norton. View

Koganei, K., Asaoka, Y., Nishimatsu, Y., & Kito, S. (2021). Women’s psychological experiences in a narrative therapy based group: An analysis of participants’ writings and Beck depression inventory–second edition. Japanese Psychological Research, 63(4), 466-475. View

Kim, H. S., & Kollak, I. (Eds.) (2006). Nursing theories: Conceptual and philosophical foundations (2nd ed.). Springer Publishing Company. View

Milner, J., & Myers, S. (2007). Working with violence: Policies and practices in risk assessment and management. Palgrave Macmillan. View

White, M. (1997). Narratives of therapists’ lives. Dulwich Centre Publications. View

Kondrat, D. C., & Teater, B. (2009). Anti-stigma approach to working with persons with severe mental disability: Seeking real change through narrative change. Journal of Social Work Practice, 23(1), 35–47. View

Kelley, P. (1996). Narrative theory and social work treatment. In F. J. Turner (Ed.), Treatment: interlocking theoretical approaches (pp. 461–479), Free Press.

Combs, G., & Freedman, J. (2016). Narrative therapy’s relational understanding of identity. Family Process, 55(2), 211 224. View

White, M. (1993). Deconstruction and therapy. In S. Gilligan & R. Price (Eds.), Therapeutic conversations (pp. 21-61), W.W. Norton.View

Lee, Y. Y. K. (2020). The landscape of one breast: Empowering breast cancer survivors through developing a transdisciplinary intervention framework in a Jiangmen breast cancer hospital in China. [Unpublished DSW thesis]. Hong Kong Polytechnic University. View

Myerhoff, B. (1982). Life history among the elderly: Performance, visibility and remembering. In J. Ruby (Ed.), A crack in the mirror. Reflective perspectives in anthropology. University of Pennsylvania Press. View

Latorre, I., (2012). Enriching the history of trauma: An interview methodology. Explorations: An E-Journal of Narrative Practice, 1(1-3). View

Lao Zhi Liao Wang. (n.d.). Why is the mourning period three years in ancient customs?

Society for Community Organization. (2021). Launch of the 2021 research report on discrimination against mainland settlers. View

Brahm, G. N. (2019). Intersectionality. Israel Studies (Bloomington, Ind.), 24(2), 157–170. View