Journal of Social Work and Welfare Policy Volume 3 (2025), Article ID: JSWWP-157

https://doi.org/10.33790/jswwp1100157Research Article

Beyond Aces: The Impact of Childhood Emotional Abuse and Adult on Adult Behavioral Outcomes in Women

Darron Garner1, PhD, LCSW-S, Jackson de Carvalho2*, PhD, and Beverly Spears3, PhD

1Associate Professor, Department of Social Work, Prairie View A&M University, Prairie View, Texas 77446, United States.

2Professor & MSW Program Director, Prairie View A&M University, Prairie View, Texas 77466, United States.

3Assistant Professor & MSW Field Director, Prairie View A&M University, Prairie View, Texas 77466, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Jackson de Carvalho, PhD, MSW, Professor & MSW Program Director, Prairie View A&M Uni versity, Prairie View, Texas 77446, United States.

Received date: 15th July, 2025

Accepted date: 30th July, 2025

Published date: 01st August, 2025

Citation: Garner, D., Carvalho, J., & Spears, B., (2025). Beyond Aces: The Impact of Childhood Emotional Abuse and Adult on Adult Behavioral Outcomes in Women. J Soci Work Welf Policy, 3(2): 157.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Childhood abuse represents a profound mental and physical health issue in the United States. Survivors often grapple with cognitive, emotional, and behavioral difficulties across the lifespan. However, the specific effects of emotional, physical, and sexual abuse have not been fully disentangled in relation to high-risk adult behaviors. The present study examined self-reported survey data from 227 women in the south-central U.S. to explore how different types of childhood abuse predict adult engagement in self-injury, substance use, and criminal activity. Multiple regression analyses revealed that emotional abuse significantly predicted self-injury (β = .15, p < .05, R² = .04), substance misuse (β = .20, p < .01, R² = .07), academic and occupational problems (β = .38, p < .001, R² = .27), misdemeanors (β = .14, p < .05, R² = .06), and felony offenses (β = .04, p = .04, R² = .04). When emotional abuse was included in the models, the predictive effects of physical and sexual abuse diminished, suggesting emotional maltreatment may have the most pervasive and enduring impact. These findings underscore the critical need for early screening and the implementation of trauma-informed, emotion focused interventions, such as Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT). Addressing emotional abuse may be essential for reducing long-term behavioral health risks and promoting resilience among survivors.

Keywords: Emotional Abuse; Adverse Childhood Experiences; Women; Self-Injury; Substance Misuse; Research

Introduction

According to Merrick et al. [1], extensive epidemiological studies have identified a statistically significant correlation between adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and the emergence of mental health and behavioral disorders in later life. This research study holds considerable implications for practice in the field of social work, psychology, and psychiatry. Additionally, a meta-analysis conducted by Choi et al. [2] revealed that childhood physical and sexual abuse can increase the likelihood of substance dependence by two to four times. Emotional abuse has been associated with self-injury and suicidality, primarily due to deficiencies in emotion regulation [3]. Nonetheless, the evidence can be inconsistent. Some population surveys indicate that controlling for co-occurring types of abuse may diminish the observed effects of sexual abuse [4]. Moreover, Walsh et al. [5] found that sexual abuse is the strongest predictor of adult violence. These discrepancies are often attributed to methodological variations among studies, many of which utilize single-item ACE checklists. Such checklists reduce complex trauma histories to binary “yes/no” responses, at times neglecting both the severity and context of the trauma [1]. This oversimplification can obscure important nuances in the findings and potentially undermine the validity of the research [1,5].

It is vital to underscore the necessity for more comprehensive assessments of ACEs. The study by Teicher and Samson [6] found that existing literature often aggregates different types of abuse—such as emotional, physical, and sexual maltreatment— into combined “total adversity” scores. This approach conceals the distinct psychological and behavioral consequences associated with each specific type of abuse. According to Liu et al. [3], by prioritizing comprehensive assessments, research studies can contribute to a more nuanced understanding of the effects of ACEs. Furthermore, it is essential to recognize that justice-system outcomes (e.g., arrests, convictions, or incarceration) are often excluded or only superficially measured in trauma studies [7]. These outcomes are not just statistics but critical markers of behavioral risk and systemic involvement. The field’s ability to detect specific pathways from early trauma to adult functioning, especially among high-risk populations like women with intersecting experiences of abuse, marginalization, and institutional contact, is significantly hindered by these methodological limitations [2]. Moreover, efforts must be made to start analyzing women’s experiences separately from men’s, as gendered pathways to harm are often overlooked [3,8].

The present study seeks to address identified gaps within the existing body of literature by employing multi-item scales that specifically focus on a sample of women from urban settings. This focus is significant because it allows us to understand the unique challenges and experiences of women in urban environments, where factors such as social isolation, economic disparities, and cultural norms may contribute to the prevalence and impact of emotional abuse [3]. This methodological approach facilitates a nuanced exploration of the relative effects of emotional, physical, and sexual abuse across five distinct adult risk domains [9]. Informed by emotion-focused theories, this investigation posits that chronic emotional maltreatment—characterized by recurrent exposure to belittlement, humiliation, rejection, or emotional unavailability— can induce enduring disruptions in neural circuits pertinent to emotion regulation, impulse control, and executive functioning [6]. Neurobiological evidence has shown that such adverse experiences correlate with alterations in the development of critical brain structures, such as the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and hippocampus, which are instrumental in governing stress responses and behavioral regulation [6,10].

The ramifications of emotional abuse are profound, potentially leading individuals to exhibit heightened stress reactivity, diminished distress tolerance, and the adoption of maladaptive coping strategies, including self-injury, substance misuse, or aggression [3]. These disruptions may have cross-domain implications, impacting various facets of functioning—including mental health, interpersonal relationships, educational attainment, and legal challenges— irrespective of the presence of physical or sexual trauma [11]. Additionally, this study aimed to increase awareness of emotional maltreatment, a type of trauma that has historically received insufficient attention, while also placing its impact in the context of more commonly acknowledged forms of childhood abuse [3,5].

The primary objectives of this study, which are crucial for enhancing our understanding of trauma and behavioral health, were as follows:

a. To estimate the prevalence and severity of various types of abuse distinctively, specifically quantifying the frequency of emotional, physical, and sexual abuse experienced in the childhood histories of the women in the sample. Furthermore, the study will evaluate the intensity and duration of these experiences.

b. To deliver a comprehensive description of the distribution of five adult behavioral outcomes by examining how these behaviors are represented within the sample. This will involve utilizing metrics such as means, standard deviations, and prevalence rates to construct a detailed profile of the behavioral health landscape among community-dwelling women with trauma histories.

The findings of this study hold significant implications for clinical practice, especially in social work, psychology, and psychiatry [12]. By understanding the distinct and combined effects of emotional, physical, and sexual abuse on adult behavioral outcomes, clinicians can apply this knowledge to tailor their interventions more effectively, thereby engaging with their patients in a more meaningful way [13,14].

The present research study aimed to test the following research questions and corresponding hypotheses:

Research Questions

1. Which subtype(s) of childhood abuse independently predict adult outcomes such as self-injury, substance misuse, problems at school or work, misdemeanor crimes, and felony crimes?

2. Do the strengths of these relationships vary across different outcome domains?

Hypotheses

H1: Childhood emotional abuse shows a statistically significant positive correlation with adult outcomes when controlling for physical and sexual abuse.

H0: Physical and sexual abuse will not independently predict outcomes once emotional abuse is included.

Literature Review

Childhood abuse and maltreatment represent a pressing public health crisis in the United States, demanding immediate and focused action [15]. In 2018, an estimated 678,000 victims of childhood maltreatment were identified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [16]. According to Ziobrowski et al. [17], an alarming 3.5 million children undergo annual investigations or differential responses from child protective services. Disturbingly, a substantial 84.5% of these young victims experience at least one form of maltreatment each year—whether it be physical, sexual, or emotional abuse, or neglect—while 15.5% face the harrowing reality of suffering from two or more forms of maltreatment concurrently [17,18].

Over the past four decades, scholars and practitioners have dedicated considerable effort to uncovering the deep-seated and enduring negative effects of childhood trauma [9]. In the 1990s, there was a prevalent belief that children possessed a remarkable resilience, often forgetting or seemingly unaffected by traumatic experiences [19]. However, an abundance of research conducted over the last three decades has illuminated a definitive correlation between early adverse experiences and a multitude of complications that manifest in both childhood and adulthood [5,17].

The repercussions of childhood abuse extend far beyond immediate physical harm, profoundly impacting a young individual’s psychological well-being, physical health, and social development [8]. Survivors often grapple with a host of serious health issues in adulthood, including ischemic heart disease, various forms of cancer, chronic lung diseases, irritable bowel syndrome, and fibromyalgia [9]. Additionally, child abuse survivors frequently adopt detrimental behavioral risk factors, such as smoking, substance abuse, inadequate nutrition, and a sedentary lifestyle [8]. The long-term effects of such trauma can surface as debilitating psychiatric symptoms, encompassing pervasive depression, anxiety, substance dependency, aggression, suicidal thoughts, a profound sense of shame, and cognitive impairments [20]. Acknowledging and understanding the significant consequences of childhood abuse is imperative; heightened awareness can pave the way for early interventions and strategies that aim to prevent a wide array of somatic and psychiatric disorders, ultimately fostering healthier futures for affected individuals [2,9].

The symptoms of depression linked to childhood abuse can significantly impact various aspects of adult life, including physical health and psychosocial well-being [21]. Research shows that severe childhood victimization, particularly sexual and physical abuse, is associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms in adulthood [22]. These traumatic experiences also increase the risk of suicidal behaviors, highlighting the urgency of this issue [3]. The effects of early trauma, with its profound and lasting impact, can shape an individual’s emotional health and overall quality of life [21,22].

A comprehensive study conducted by Hall et al. [23] delved into the intricate relationship between childhood abuse and its long-lasting effects on mental health. The study revealed that while many victims of such traumatic experiences face significant psychiatric challenges later in life, a remarkable subset of individuals demonstrate extraordinary resilience. For instance, a longitudinal study conducted by Clark et al. [24] uncovered that approximately one-third of at risk Hawaiian children—despite enduring substantial early life hardships—grew into well-adjusted and thriving adults.

It is noteworthy that the presence of protective factors at various levels—social, communal, relational, and individual—proves essential in fostering this resilience [25]. These individual traits encompass a spectrum of inherent qualities, alongside the skills necessary for effectively managing one’s thoughts and emotions [18]. Nevertheless, a significant gap persists in the research pertaining to specific personal factors that may mitigate depressive symptoms in adulthood following experiences of childhood abuse [26]. Addressing this gap holds the potential to unlock innovative strategies for healing and empowerment, guiding those affected toward a path of recovery and growth [23,25].

Childhood Maltreatment and Abuse

Childhood maltreatment and trauma represent critical and pervasive issues, encapsulating all forms of neglect and abuse experienced during early developmental stages. As defined by the Children’s Bureau [15], child maltreatment encompasses both acts of commission (i.e., abuse) and acts of omission (i.e., neglect). Acts of commission involve overtly harmful behaviors, including physical violence, sexual abuse, emotional manipulation, and specific actions that jeopardize a child's safety and well-being [27]. These specific actions could include leaving a child unsupervised in a dangerous environment or exposing them to harmful substances [6]. Conversely, acts of omission pertain to the failure to provide sufficient care or protection necessary to fulfill a child's fundamental physical, emotional, or educational needs [27,28].

The origins of childhood maltreatment are multifaceted, encompassing a range of contributing factors such as emotional, physical, or sexual abuse; emotional and physical neglect; exposure to natural disasters; substance abuse within the household; parental separation or divorce; the incarceration of a household member; community violence; and medical injuries [29]. Understanding these complex origins is crucial for developing a comprehensive approach to addressing childhood maltreatment [27]. Particularly, childhood abuse implicates the presence of physical, sexual, or emotional harm, as well as the risk of maltreatment perpetrated by primary caregivers (e.g., parents, foster parents, or legal guardians) or secondary caregivers (e.g., relatives, coaches, or babysitters), underscoring the crucial influence of these individuals in a child's developmental trajectory [29,30].

The widespread occurrence and long-lasting effects of childhood physical and sexual abuse are well-documented in the relevant literature and raise significant concerns [22]. Research shows that in nonclinical adult populations in the United States and Canada, the reported rates of childhood physical abuse range from approximately 10% to 31% among men, and from 6% to 40% among women [31]. These statistics highlight the urgent need for interventions to address the harmful impacts of childhood maltreatment. Childhood physical abuse is defined as the intentional use of force or aggression against a child, which can lead to physical injury [2]. The severity of physical abuse can vary, ranging from actions that leave visible marks on the body to those that cause permanent deformity, disability, or even death [22] Physical abuse can involve actions such as hitting, kicking, choking, burning, or poisoning [22,32].

In addition, studies in U.S. nonclinical adult samples indicate that the prevalence of childhood sexual abuse ranges from 28% to 33% in women and from 12% to 18% in men [32]. Childhood sexual abuse is defined as a caregiver's unwanted attempt or act of sexual contact or exploitation involving a child [31]. Such sexual abusive acts, even with the child's assent, may involve contact with another individual that includes penetration of the mouth, vulva, penis, or anus [4]. Furthermore, these acts can also involve penetration through the use of a hand, finger, or object [33]. Childhood sexual abuse is reported at prevalence rates between 28% and 33% among female individuals and between 12% and 18% among male individuals within nonclinical adult populations in the United States [31]. Both childhood physical abuse and sexual abuse are recognized as forms of maltreatment that may result in long-lasting negative consequences for affected individuals [32]. These findings underscore the significant prevalence of childhood maltreatment and its potential to contribute to enduring psychological and emotional challenges in adulthood [24,31].

The purpose of this study is to explore whether emotional, physical, and sexual childhood abuse differently predict a range of high-risk behaviors in urban women. Specifically, it aims to determine whether each form of abuse uniquely contributes to outcomes such as self injury, substance misuse, educational and vocational disruptions, and involvement with the justice system. By isolating the independent effects of these types of traumas, the study goes beyond cumulative adversity models, providing a unique and nuanced understanding of how early relational harms influence later behavioral risks as insinuated by Merrick et al. [1]. This depth of understanding is particularly important for creating gender-responsive, trauma informed interventions that address the root causes of adult behavioral health challenges [31]. The findings have implications for assessment protocols, indicating an urgent need for comprehensive screening tools that capture the whole emotional landscape of early abuse experiences [31,34].

Method

A quantitative, cross-sectional study design was used to analyze secondary data obtained from the comprehensive Trauma Research survey conducted in March 2025. This design was chosen to explore the relationships between childhood trauma subtypes and various adult behavioral outcomes at a single point in time without manipulating any variables [35]. The data, initially collected for program evaluation and exploratory research, consisted of self reported responses from a convenience sample of adult behavioral health service users. Data collection took place over six weeks, during which participants completed a Qualtrics survey using a unique PIN number, following informed consent procedures and best research practice procedures [36]. The cross-sectional nature of the study provided a snapshot of participants' lifetime experiences and current behaviors, with the findings having direct implications for real-world community mental health contexts. This allowed for the testing of multivariate relationships between early exposure to abuse and adult functioning within a real-world community mental health context [35,37].

The target population for this study consisted of adult behavioral health service users affiliated with a community-based mental health and trauma recovery agency in the south-central region of the United States. These individuals were either currently receiving or had recently accessed outpatient or supportive services related to trauma, emotional distress, or behavioral issues. The agency's active client roster defined the sampling frame during the study period. It included individuals identified by staff as suitable for participation based on preliminary screening for trauma history.

Criteria of Inclusion– To participate in the study, individuals had to meet the following criteria: (1) be 18 years of age or older, ensuring adult consent and alignment with legal definitions of adulthood; (2) self-identify as female, which aligns with the study’s focus on women's trauma and behavioral outcomes; (3) report a history of any form of childhood adversity, including abuse, neglect, or household dysfunction; and (4) demonstrate sufficient English literacy to read and complete the study materials independently or with minimal assistance. These inclusion criteria were established to ensure relevance to the study’s focus and to guarantee that participants could understand and accurately respond to the survey instruments [38]. Additionally, applying these selection criteria helped the researcher gather rich and sufficient data to address the research questions [36,39].

The study employed a consecutive convenience sampling method, where trained staff or study personnel engaged eligible participants during their routine appointments or group sessions [31]. Of the 249 individuals initially approached, 201 (83.7%) identified as women, consented to participate, and provided informed consent. The analysis focused on three predictor variables—emotional, physical, and sexual abuse—entered simultaneously into each model. With these variables, the study achieved an 86% statistical power to detect an effect size of f² ≥ 0.25, adhering to a significance level of α = .05. This level of statistical power indicates robust sensitivity in identifying significant relationships between trauma subtypes and subsequent adult behavioral outcomes [37]. All participants resided within a large metropolitan area in the south-central region of the United States. In considering the external validity of these findings, it is imperative to account for both demographic and geographic factors [40]. The study underscores the significance of these factors, as patterns of abuse exposure and help-seeking behaviors may exhibit variability across different regions or cultural contexts, thereby enhancing the relevance and applicability of the research [31,37].

Instrumentation

The Traumatic Child Maltreatment and Adult Behavior Outcome Scale (TCMABOS) was used in the data collection for the study. All measurement items and subscales used in the study were adapted from well-established instruments, specifically the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) questionnaire and various Lifetime Risk Behavior Inventories commonly used in trauma and behavioral health research [32]. These instruments have been widely validated across diverse populations and are known for their utility in assessing early life adversity and subsequent risk-related behaviors. For this study, item sets were carefully selected and modified to ensure they were developmentally appropriate, contextually relevant, and aligned with the lived experiences of urban-dwelling women receiving behavioral health services, thereby tailoring the study to their specific needs [32,40].

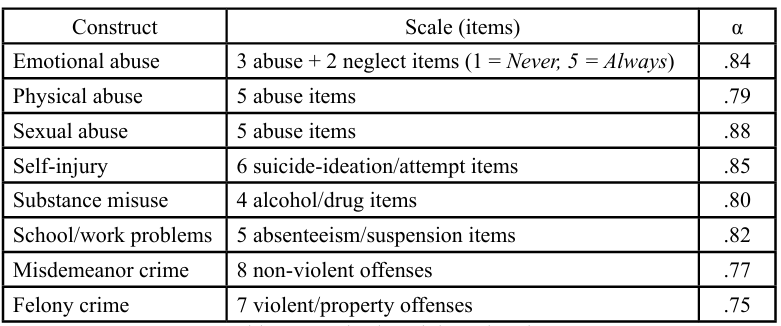

Each abuse subtype—emotional, physical, and sexual—was represented by multiple Likert-scale items capturing frequency, severity, and relational context. Similarly, outcome domains such as self-injury, substance use, school/work problems, and criminal behavior were assessed using multiple behaviorally specific items [40]. Composite scores were calculated by averaging responses across each domain. Internal consistency was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha, and all scales demonstrated acceptable to strong reliability coefficients (α = .75–.88), supporting their use in subsequent analyses. This rigorous approach to scale development ensured both psychometric integrity and sensitivity to the multidimensional nature of trauma and its effect [31,35].

Procedures

The study protocol received approval from the Prairie View A&M University Institutional Review Board (IRB #2025-062). Participants provided written informed consent, were guaranteed anonymity, and received a unique PIN to access the Qualtrics survey either on a clinic computer or their personal devices. The average completion time for the study survey was approximately 25 minutes to maximize reliability [37]. After the six-week data collection period, all responses were exported from Qualtrics into SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) for data cleaning and analysis. During this transfer, the researcher ensured data integrity by properly labeling variables, recoding categorical responses, managing any missing data, and calculating composite scores [40]. SPSS facilitated effective data management, reliability testing, and both descriptive and inferential statistical analyses. This included the use of advanced multivariate regression models to examine the relationships between subtypes of childhood abuse and adult behavioral outcomes, ensuring a robust analysis [36,40].

Data Analysis

SPSS version 28 and statsmodels (Python 3.11) were utilized for the data analysis [36]. Composite scores were calculated as the means of valid items, defined as those with ≥ 80% completion. Pearson correlations were employed to assess bivariate relationships [37]. Five separate ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions analyzed each adult outcome about the three abuse predictors, with a significance level set at p < .05 (two-tailed), underscoring the study's key findings, which are of significant importance. Multicollinearity diagnostics— including tolerance and VIF—were conducted on all predictors. The resulting values indicated minimal overlap (VIF range = 1.15–1.58), which supports the robustness of the regression estimates [37,41].

Results

In a sample of 201 women, there was widespread reported exposure to childhood abuse, with particularly high rates of physical and emotional maltreatment. Using a threshold of "Sometimes" or more frequently on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Never, 5 = Always), the following prevalence rates emerged:

• Emotional abuse: 70% of participants reported experiencing verbal attacks, rejection, or emotional neglect at least "sometimes" during childhood, indicating a significant burden of psychological harm.

• Physical abuse: 89% of the study participants reported being subjected to physical aggression—such as hitting, pushing, or threats with objects—at least "sometimes", highlighting the high incidence of direct bodily harm within this clinical sample.

• Sexual abuse: 51% of respondents indicated they had experienced unwanted sexual contact or coercion at least "sometimes" in childhood, confirming that more than half of the sample endured sexually invasive trauma during their formative years.

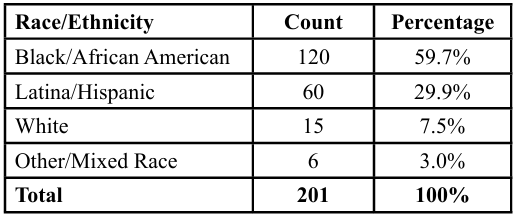

Demographics and characteristics of the final sample of 201 women participants by race/ethnicity category are presented in Table 2.

The sample primarily consisted of Black/African American women (59.7%), followed by Latina/Hispanic women (29.9%). Together, these two groups made up nearly 90% of the total sample, highlighting a strong representation of women of color. White women accounted for only 7.5%, while participants identifying as Other/Mixed Race comprised 3.0%. This racial and ethnic composition likely reflects the demographic characteristics of the geographic area or service population from which the sample was drawn, possibly an urban or underserved community in the South-Central United States. The significant representation of Black and Latina women is particularly relevant for research focused on trauma, behavioral health, or help seeking behaviors, given the historical and systemic barriers that these groups often encounter when accessing mental health services [2,42].

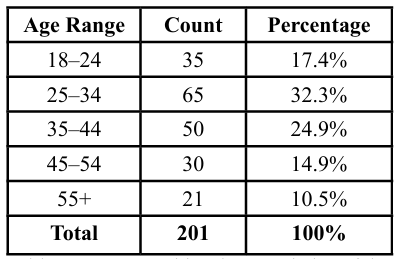

The sample is relatively young, with nearly three-quarters (74.6%) of participants between the ages of 18 and 44. The largest subgroup is aged 25–34 (32.3%), followed by those aged 35–44 (24.9%) and 18–24 (17.4%). Representation drops significantly after age 45, with 14.9% of participants aged 45–54 and 10.5% aged 55 or older. It is essential to highlight the underrepresentation of older women (55+), which may reflect differences in help-seeking behavior, recruitment efforts, or access to services across generations [2,23].

When considering the racial and age distributions together, it becomes clear that the majority of the sample consists of young to middle-aged women of color, particularly Black and Latina women. This demographic often faces multiple vulnerabilities, such as racial discrimination, economic insecurity, and exposure to violence [43]. Therefore, research, services, and advocacy must be approached from an intersectional and trauma-informed perspective [7,43].

In addition to measuring abuse histories, the study assessed current or lifetime engagement in five high-risk behavioral domains, also on a 5-point Likert scale [37]. The mean scores for each outcome were as follows: Self-injury (e.g., suicide ideation or attempts): M = 2.78, indicating that, on average, participants reported self-harming behaviors between "rarely" and "sometimes." Substance misuse (e.g., alcohol or drug problems): M = 1.53, suggesting low but present levels of engagement, with responses typically falling between "never" and "rarely." School/work problems (e.g., suspensions, job loss): M = 1.65, pointing to occasional disruptions in educational or vocational functioning. Misdemeanor criminal activity (e.g., shoplifting, disorderly conduct): M = 1.15, indicating infrequent but notable involvement in lower-level legal infractions. Felony criminal behavior (e.g., assault, theft): M = 1.05, reflecting minimal endorsement of more serious criminal activity, though still present in the sample. These descriptive statistics confirmed that while not all participants exhibited the same levels of behavioral risk, many experienced overlapping patterns of trauma and dysfunction [43]. The high prevalence of abuse—particularly emotional and physical—and the measurable presence of risk behaviors across domains, support the need for a trauma-informed framework to guide both clinical practice and further analysis [7,44].

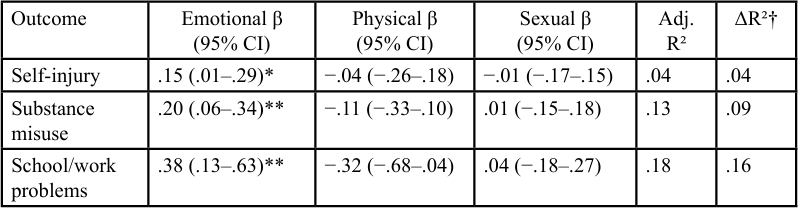

To evaluate the distinct impact of different types of childhood abuse on adult behavioral outcomes, we conducted five separate ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models—one for each outcome variable: self-injury, substance misuse, problems at school or work, misdemeanor crime, and felony crime [45]. Each model included emotional abuse, physical abuse, and sexual abuse as simultaneous predictors. The standardized beta coefficients (β) and their corresponding p-values for each predictor are summarized below, along with the adjusted R², which indicates the proportion of variance in each outcome explained by the model, accounting for the number of predictors used [43,45].

Across all five behavioral outcomes, emotional abuse emerged as the only statistically significant and consistent independent predictor, even when controlling for the effects of physical and sexual abuse [45]. This finding has profound implications, supporting the hypothesis that emotional maltreatment plays a central role in shaping later risk behaviors among women exposed to trauma, which is congruent with the findings of Scoglio et al. [25]. For self-injury, emotional abuse was positively associated with lifetime incidents (β = .15, p = .045). In contrast, physical and sexual abuse were unrelated, suggesting that internalized distress and dysregulation may stem primarily from emotional harm. In the substance misuse model, emotional abuse again showed a strong positive relationship (β = .20, p = .007), implying that emotional trauma may underlie the development of maladaptive coping mechanisms like drug and alcohol use, which align with the findings of Choi et al. [2] and Schuler et al. [46].

These findings have significant implications for our understanding of how abuse affects adaptive functioning. The results indicated that emotional abuse had the strongest predictive relationship with disruptions in school and work (β = .38, p = .005). Conversely, physical abuse showed a marginally significant negative relationship (β = −.32, p = .08). This may suggest differences in adaptive functioning based on various profiles of abuse, similar to the findings of Cohen et al. [32]. For misdemeanor criminal behavior, emotional abuse retained a robust positive association (β = .14, p = .002). In contrast, neither physical nor sexual abuse reached significance, indicating a behavioral pathway from emotional harm to externalized, non-violent legal infractions. In the model for felony crime, emotional abuse remained a modest but statistically significant predictor (β = .04, p = .029), and physical abuse approached significance (β = .04, p = .09), suggesting a potential interaction or shared contribution for more serious offenses [32,47].

The adjusted R² values ranged from 0.04 for self-injury to 0.27 for misdemeanor crime. This indicates that while histories of abuse explain a modest to moderate amount of variance in adult behavioral outcomes, emotional abuse consistently plays a significant role in these effects [47]. Notably, sexual abuse was found to be non significant across all five models. This underscores the importance of examining different types of abuse in trauma research rather than assuming they have equal impacts. These findings provide compelling evidence that emotional abuse, often overlooked in both clinical and research contexts, is a key factor in adult behavioral outcomes, potentially more so than physical or sexual abuse alone [3,32].

While emotional abuse emerged as a robust and consistent predictor of adult behavioral outcomes in this study, physical and sexual abuse did not independently predict any of the five outcomes once emotional abuse was accounted for. These non-significant findings do not negate the seriousness of physical or sexual abuse; instead, they underscore the complexity of trauma's psychological impact and the potential mediating or confounding role of emotional maltreatment. The absence of statistically significant beta coefficients for physical and sexual abuse may suggest that their long-term behavioral effects are entangled with co-occurring emotional harm, such as being silenced, disbelieved, or neglected in the aftermath of abuse.

Discussion

The findings supported the directional hypothesis, indicating that emotional maltreatment was the only subtype of abuse that remained a statistically significant predictor of all five adult behavioral outcomes. It accounted for between 4% and 27% of the variance, depending on the specific outcome, highlighting its widespread and significant impact. These results are consistent with biosocial models of emotion dysregulation, which suggest that individuals who experience chronic emotional invalidation during childhood—such as being ignored, belittled, or frequently criticized—develop impaired emotion regulation systems [3]. This emotional dysregulation can lead to a variety of externalizing behaviors (e.g., aggression, substance use, legal troubles) and internalizing behaviors (e.g., self injury, social withdrawal, disengagement from academic activities). Importantly, these behaviors are often maladaptive ways to cope with distress, underscoring the need for early intervention and support [3,48].

The study results indicated that emotional abuse is not merely a secondary trauma; it is a primary disruptor of development that leads to enduring behavioral patterns into adulthood. The strong and consistent effects of emotional abuse, even when controlling for physical and sexual abuse, highlight the significant psychological harm it inflicts [32]. This harm may be more profound and lasting than previously acknowledged in trauma research. The substantial effects of emotional abuse have essential implications for our theoretical understanding. It suggests that pathways of emotional dysregulation might serve as a critical mechanism linking early emotional harm to later functional impairments across various areas of life [3]. In contrast to findings from some large-scale population studies that identify childhood sexual abuse as a major predictor of long-term behavioral and psychological damage, our analysis indicates that the impact of sexual abuse diminishes in every multivariate model once emotional abuse is taken into account as a covariate. This implies that the unique effects of sexual abuse may, in part, be explained by the concurrent emotional maltreatment that often accompanies or follows sexual trauma—particularly when the abuse is ignored, minimized, or not believed by caregivers [3,49].

Furthermore, results support Maniglio’s [49] assertion that the psychological impact of trauma is influenced more by the processing and validation (or invalidation) of that trauma within interpersonal and familial contexts than by the specific type of traumatic event itself. Emotional invalidation—such as neglect, denial, or shaming in response to a child's disclosure—can mediate or even exacerbate the effects of various forms of trauma by intensifying feelings of shame, confusion, and emotional disconnection [4]. Thus, emotional abuse and neglect are not merely additional adversities; they represent critical contextual factors that elevate the severity or chronicity of trauma responses, particularly those arising from physical or sexual abuse [4,6].

The study findings challenge the traditional hierarchy of trauma that often ranks sexual abuse as the most severe in terms of predictive value [19]. Instead, they underscore the necessity for integrative models that take into account the emotional context in which all forms of abuse occur. This highlights the importance of screening for and addressing emotional maltreatment in both research and clinical practice, even when more overt forms of abuse are present.

While gender-specific analyses were pivotal to this study, the intersection of gender with race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status likely influences both the experience of emotional maltreatment and the availability of protective resources [31]. For example, structural racism and poverty may amplify the detrimental impacts of childhood emotional invalidation by restricting access to supportive school environments or trauma-informed care. Future research should embrace intersectional frameworks to further explore how multiple identities collectively shape the observed pathways [7,31].

Limitations

The use of a convenience sample drawn from a single community behavioral health agency in the south-central United States—and predominantly composed of Black and Latina women—limits the generalizability of findings to other racial/ethnic groups or geographic regions. However, this sample also represents a critically underserved population often excluded from trauma research. The inclusion of women of color in community-based care settings offers valuable insight into the real-world manifestations of abuse and behavioral outcomes among populations disproportionately affected by systemic inequities [50]. This focus on underserved populations is not just valuable, but it also makes the audience, who may be part of these communities or working with them, feel included and important. These findings may have particular relevance for tailoring trauma informed interventions in urban, racially diverse communities [13]. All data were collected via self-report surveys, which introduces the potential for response bias.

Participants may have under-reported sensitive or stigmatized experiences such as childhood sexual abuse or criminal activity due to shame, fear of judgment, or memory distortion [51]. Conversely, over-reporting may occur in individuals who overattribute current struggles to past trauma or who seek validation through clinical settings. These biases could lead to either under- or overestimation of the true prevalence and severity of abuse and its behavioral correlates [52]. Nonetheless, self-reporting remains a widely accepted method in trauma research, particularly for capturing subjective experiences that may not be accessible through administrative or observational data. The anonymity and privacy of the survey format likely increased disclosure relative to in-person interviews.

The study did not include several potentially significant covariates that could confound or moderate the relationships under investigation. For instance, variables such as current mental health diagnoses (e.g., PTSD, depression), protective factors (e.g., social support, resilience), and treatment history were not assessed. These factors could significantly influence both the likelihood of reporting trauma and the expression of adult behavioral outcomes. Their omission limits the ability to fully understand the contextual and interactive effects that shape trauma recovery or risk pathways. Despite this limitation, the study’s focus on disaggregating abuse subtypes offers a novel and parsimonious approach that lays essential groundwork for future multivariate and longitudinal research. This emphasis on future research not only makes the audience feel hopeful and inspired, but it also provides direction for subsequent studies to incorporate more complex biopsychosocial models [20]. The clarity of this design enhances interpretability while giving direction for subsequent studies to incorporate more complex biopsychosocial models.

Implications For Practice

The findings strongly support the need for routine screening of emotional maltreatment in behavioral health assessments, especially when working with adult women. Many practitioners rely on standard ACEs (Adverse Childhood Experiences) checklists. However, these tools often oversimplify emotional abuse to a single item or omit it entirely, thereby failing to capture its frequency, intensity, and relational context. To address this, clinicians should consider using expanded trauma inventories or structured interviews. These tools comprehensively explore aspects such as emotional invalidation, rejection, and verbal aggression, empowering practitioners with better tools for their work.

When it comes to intervention, the results underscore the potential of evidence-based therapies like Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) and Skills Training in Affective and Interpersonal Regulation (STAIR). These approaches are specifically designed to address emotion dysregulation, which is likely a key mechanism linking emotional abuse to behavioral issues [3]. Given the association of emotional abuse with various risks, such as self-injury, substance misuse, and legal problems, the use of these tailored interventions could offer broad-spectrum benefits for trauma survivors facing regulatory challenges [3,5].

From a policy perspective, the study emphasizes the importance of prioritizing the prevention of emotional abuse at the same level as physical or sexual maltreatment. This emphasis should make policymakers feel the urgency and necessity of their actions. Funding sources and legislative initiatives should focus on developing and promoting parent-training programs, positive discipline curricula, and early childhood interventions that encourage emotionally supportive caregiving and discourage verbal hostility, shaming, or neglect. Programs like Nurturing Parenting, Triple P (Positive Parenting Program), and Circle of Security can be particularly effective in breaking the intergenerational cycles of emotional harm [13,48].

This study opens several avenues for future research. To establish causal pathways and strengthen theoretical models, researchers should pursue larger, longitudinal designs that track individuals from childhood into adulthood. Such studies could identify mediating mechanisms—such as emotion dysregulation, attachment insecurity, or neurobiological stress reactivity—that explain how emotional abuse leads to behavioral dysfunction. Additionally, future research should examine moderating variables that may buffer or exacerbate these effects, including social support, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and access to trauma-informed care. Expanding the sample size and diversity would also allow for subgroup analyses that reveal how cultural, gendered, and systemic factors interact with personal trauma histories. Ultimately, a more nuanced and intersectional approach is essential for informing effective and equitable interventions and policies aimed at reducing the long-term impact of emotional abuse.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that among women with histories of childhood trauma, emotional abuse is the most consistent and significant predictor of adult high-risk behaviors—surpassing the predictive effects of physical and sexual abuse. These findings call for expanded clinical screening and trauma-informed interventions that specifically target emotional maltreatment, which has often been overlooked in both research and practice. Addressing emotional abuse early and comprehensively is essential to reducing long-term behavioral risks and fostering resilience in survivors.

Conflicts of interest:

The researcher declares no conflict of interest, and the study received no funding.

References

Merrick, M. T., Ford, D. C., Ports, K. A., & Guinn, A. S. (2019). Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences from the 2011–2014 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. JAMA Pediatrics, 173(3), e190740. View

Choi, K., DiNitto, D., & Choi, B. (2022). Childhood abuse and adult substance use: A meta-analysis. Addictive Behaviors, 130, 107266.

Liu, R. T., Trout, Z. M., Hernandez, E. M., Cheek, S. M., & Gerlus, N. (2020). Emotional abuse and non-suicidal self injury among college women: The mediating role of emotion dysregulation. Journal of Affective Disorders, 273, 247–254.

Talmon, A., & Ginzburg, K. (2018). “Body self” in the shadow of childhood sexual abuse: The long-term implications of sexual abuse for male and female adult survivors. Child Abuse & Neglect, 76, 416–425. View

Walsh, K., Koenen, K. C., Aiello, A. E., Uddin, M., & Galea, S. (2019). Childhood sexual abuse and adulthood interpersonal violence risk in women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 87(1), 106–118.

Teicher, M. H., & Samson, J. A. (2016). Annual research review: Enduring neurobiological effects of childhood abuse and neglect. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57(3), 241–266. View

Bath, H. (2015). The three pillars of trauma-informed care: Strengthening the therapeutic milieu in residential treatment. Reclaiming Children and Youth, 23(4), 17–24. View

Curran, E., Adamson, G., Stringer, M., & Rosato, M. (2021). Adverse childhood experiences and risky behaviors in adulthood: Sex-specific pathways. Child Abuse & Neglect, 119, 104721.

Abajobir, A. A., Kisely, S., Williams, G., Strathearn, L., Clavarino, A., & Najman, J. M. (2017). Does substantiated childhood maltreatment lead to poor quality of life in young adulthood? Evidence from an Australian birth cohort study. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 26(7), 1697–1702. View

Trompetter, H. R., Kleine, E. de, & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2017). Why Does Positive Mental Health Buffer Against Psychopathology? An Exploratory Study on Self-Compassion as a Resilience Mechanism and Adaptive Emotion Regulation Strategy. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 41, 459–468. View

Chasnoff, I. J., Barber, G., Brook, J., & Akin, B. A. (2018). The Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act: Knowledge of health care and legal professionals. Child Welfare, 96(3), 41–58. View

Taghavi, I., & Kia-Keating, M. (2022). Adverse childhood experiences and yoga as “a practice of liberation.” Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 16(Suppl 1), S265–S273. View

Barnard, L. K., & Curry, J. F. (2011). Self-compassion: Conceptualizations, correlates, & interventions. Review of General Psychology, 15, 289–303. View

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024a). Adult BMI Categories. View

Children’s Bureau (2024). Child Maltreatment 2022. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. View

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2022). Fast Facts: Preventing Child Abuse & Neglect. View

Ziobrowski, H. N., Buka, S. L., Austin, S. B., Duncan, A. E., Sullivan, A. J., Horton, N. J., & Field, A. E. (2022). Child and adolescent abuse patterns and incident obesity risk in young adulthood. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 63(5), 809–817. View

World Health Organization. (2022). Child maltreatment. View

Ressel, M., Lyons, J., & Romano, E. (2018). Abuse characteristics, multiple victimisation and resilience among young adult males with histories of childhood sexualabuse. Child Abuse Review, 27(3), 239–253. View

WHO (2002). Global report on violence and health. Geneva, Switzerland: Author Williamson, S. (2022). The biopsychosocial model: not dead, but in need of revival. BJPsych Bulletin, 46(4), 232–234. View

Gul, A., Gul, H., Erberk Özen, N., & Battal, S. (2017). Differences between childhood traumatic experiences and coping styles for male and female patients with major depression. Turk Psikiyatri Dergisi, 28(4), 1–9. View

Afifi, T. O., MacMillan, H. L., Boyle, M., Cheung, K., Taillieu, T., Turner, S., & Sareen, J. (2016). Child abuse and physical health in adulthood. Health Reports, 27(3), 10–18. View

Hall, K., Stafford, J., & Cho, B. (2023). Women receive more positive reactions to childhood sexual abuse disclosure and negative reactions are associated with mental health symptoms in adulthood for men and women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 38(15/16), 8803–8823. View

Clark, K. A., Talan, A., Cabral, C., Pachankis, J. E., & Rendina, H. J (2021). Longitudinal associations between childhood sexual abuse-related PTSD symptoms and passive and active suicidal ideation among sexual minority men. Child Abuse & Neglect, 122. View

Scoglio, A. A. J., Kraus, S. W., Saczynski, J., Jooma, S., & Molnar, B. E. (2021). Systematic review of risk and protective factors for revictimization after child sexual abuse. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 22(1), 41–53. View

Bayly, B. L., Hung, Y. W., & Cooper, D. K. (2022). Age-varying associations between child maltreatment, depressive symptoms, and frequent heavy episodic drinking. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 51(5), 927–939. View

Mason, S. M., Austin, S. B., Bakalar, J. L., Boynton-Jarrett, R., Field, A. E., Gooding, H. C., Holsen, L. M., Jackson, B., Neumark-Sztainer, D., Sanchez, M., Sogg, S., Tanofsky- Kraff, M., & Rich-Edwards, J. W. (2016). Child maltreatment’s heavy toll. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 50(5), 646–649. View

Child Welfare Information Gateway (2015). Understanding the effects of maltreatment on brain development. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau. View

Meng, X., Fleury, M.-J., Xiang, Y.-T., Li, M., & D’Arcy, C. (2018). Resilience and protective factors among people with a history of child maltreatment: A systematic review. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology: The International Journal for Research in Social and Genetic Epidemiology and Mental Health Services, 53(5), 453–475. View

Peeters, L., Vandenberghe, A., Hendriks, B., Roelens, K., Keygnaert, I., & Gilles, C. (2019). Current care for victims of sexual violence and future sexual assault care centres in Belgium: the perspective of victims. BMC International Health & Human Rights, 19(1), N.PAG. View

Rechenberg, T., & Schomerus, G. (2023). The stronger and the weaker sex - gender differences in the perception of individuals who experienced physical and sexual violence in childhood. A scoping review. Child Abuse & Neglect, 140. View

Cohen, J. R., Menon, S. V., Shorey, R. C., Le, V. D., & Temple, J. R. (2017). The distal consequences of physical and emotional neglect in emerging adults: A person- centered, multi-wave, longitudinal study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 63, 151–161. View

Basile, K. C., Smith, S.G., Breiding, M.J., Black, M.C., & Mahendra, R.R. (2014). Sexual Violence Surveillance: Uniform Definitions and Recommended Data Elements, Version2.0. Atlanta (GA): National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. View

Inwood, E., & Ferrari, M. (2018). Mechanisms of Change in the Relationship between Self-Compassion, Emotion Regulation, and Mental Health: A Systematic Review. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 10(2), 215–235. View

Lawson, T., Faul, A., & Verbist, A.N. (2019). Research and Statistics for Social Workers. Routledge. ISBN: 9781138191037 View

Batchelor, A. (2019). Statistics in Social Work: An Introduction to Practical Applications. Columbia University Press. View

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2019). Using Multivariate Statistics (7th ed.). Pearson. View

Arifin, S. R. (2018). Ethical considerations in qualitative study. International Journal of Care Scholars, 1(2), 30-33. View

Schreier, M. (2018). Sampling and generalisation. In U. Flick (Ed.), The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Data Collection (pp. 84-96). SAGE. View

DeCarlo, M., Cummings, C., & Agnelli, K. (2021). Graduate Research Methods in Social Work. ISBN: 9781949373219 Available online at: https://open.umn.edu/opentextbooks/ textbooks/1041 View

Morgan, S. L., & Winship, C. (2023). Counterfactuals and Causal Inference: Methods and Principles for Social Research (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press. View

Downing, M. J., Jr., Benoit, E., Coe, L., Brown, D., & Steen, J. T. (2022). Examining cultural competency and sexual abuse training needs among service providers working with black and latino sexual minority men. Journal of Social Service Research, 49(1), 79-92. View

Du Mont, J., Johnson, H., & Hill, C. (2021). Factors associated with posttraumatic stress disorder symptomology among women who have experienced sexual assault in Canada. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(17/18), NP9777-NP9795. View

Marotta, P. (2022). Assessing the victimization-offending hypothesis of sexual and non- sexual violence in a nationally representative sample of incarcerated men in the United States: Implications for trauma-informed practice in correctional settings. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(21/22), NP20212 NP20235. View

Raudenbush, S. W., & Bryk, A. S. (2022). Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications. View

Schuler, M. S., Vasilenko, S. A., & Lanza, S. T. (2015). Age varying associations between substance use behaviors and depressive symptoms during adolescence and young adulthood. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 157, 75–82. View

Caravaca-Sánchez, F., Ignatyev, Y., & Mundt, A. P. (2019). Associations between childhood abuse, mental health problems, and suicide risk among male prison populations in Spain. View

Yun, S. H., & Fiorini, L. (2020). Exploration of mental health outcomes of community- based intervention programs for adult male survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Groupwork, 29(2). View

Maniglio, R. (2010). Child sexual abuse in the etiology of violence: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 10(1), 31–44. View

Brown, R. C., Heines, S., Witt, A., Braehler, E., Fegert, J. M., Harsch, D., & Plener, P. L. (2018). The impact of child maltreatment on non-suicidal self-injury: data from a representative sample of the general population. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 1–8. View

Knabb, J. (2018). The compassion-based workbook for Christian clients: Finding freedom from shame and negative self-judgments. New York: Routledge. View

Sander, C., Ulke, C., & Speerforck, S. (2021). Stigma as a barrier to addressing childhood trauma in conversation with trauma survivors: A study in the general population. PLoS ONE, 16(10), 1–19. View