Journal of Social Work and Welfare Policy Volume 3 (2025), Article ID: JSWWP-159

https://doi.org/10.33790/jswwp1100159Research Article

Examining the Role of Trial Home Visits and the Relationship to Foster Care Re-Entry in the U.S.

Richard P. Barth*, Terry Shaw, Linda-Jeanne M. Mack, and Haelim Lee

School of Social Work, University of Maryland, 620 West Lexington St, Baltimore, MD 21201, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Richard P. Barth, PhD, MSW, Professor, School of Social Work, University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD 21201, United States.

Received date: 26th June, 2025

Accepted date: 20th August, 2025

Published date: 22nd August, 2025

Citation: Barth, R. P., Shaw, T., Mack, L. J. M., & Lee, H., (2025). Examining the Role of Trial Home Visits and the Relationship to Foster Care Re-Entry in the U.S.. J Soci Work Welf Policy, 3(2): 159.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Re-entry of children into out-of-home care following reunification has primarily been examined through a lens on parent and child characteristics and maltreatment risk factors. This paper provides a review for interested practitioners, researchers, and policymakers to access available information to prevent re-entries for families in the future. This study examines publicly sourced data and policies to offer the clearest national picture of reunification outcomes. Results of this study showed that information about re-entry and services to prevent re-entry are not consistently collected, that trial home visits appear to be a key program but is not well described or studied, and there are ample opportunities to improve our understanding of how trial home visits are related to re-entry that could be easily realized. Policy recommendations to achieve this improvement are extended and include clarification that (1) funding for trial home visits is available through the Title IVE entitlement (and does not need to be taken from the Title IVB block grant) even if a separate NGO provides the service; (2) reduction of re-entry from return home in ways that are not a threat to the child’s safety (i.e., they were managed returns to out of home care) and all re-entries should not be counted against the agencies performance; and integration of child abuse and foster care data so that the kinds of child abuse reports (if any are made at all) that are related to re-entry can be better understood and prevented.

Keywords: Re-entry, Foster Care, Reunification, Permanency, Placement Stability, Family Preservation

Introduction

American child welfare services policy includes the premise that reasonable efforts will be made to keep children at home or, if they need to be placed into out of home care for their safety, efforts will be made to reunify them to their home of origin [1]. For children who are removed, the preferred permanency option is for that child to be safely returned to their parent(s) within approximately one year. The policy expectation is that services provided to the family while the child was in out-of-home placement will enhance familial stability after reunification and the family can permanently remain intact. After reunification, it is not uncommon for children and youth to experience another removal (called “reentry”). Approximately 20% of children and youth who entered out-of-home placement were considered re-entering in fiscal year 2022 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS)). Re-entries occur for a number of reasons including, following a new report of child maltreatment, legal or child welfare system (CWS) decision makers deciding a child is at risk for some type of maltreatment, or because parents voluntarily decide they cannot care for their child. When reunification efforts fail, there may be additional trauma for children and their families [2,3], however, there has been little attention paid by policymakers to re-entry prevention.

Previous research indicates that re-entry rates after reunifications vary markedly across the U.S. For example, a longitudinal study using administrative data from 20 states found that, over time, 27% of children will eventually re-enter after reunification, with the majority of reentries occurring within the first 2 years after reunification [4]. Another study, a review examining interventions addressing re-entry interventions found that an average of 20% of children and youth returned to foster care after a reunification with their parents [5] which is in line with the most current Children’s Bureau Data [6]. Other studies have found rates as high as 37% and as low as 11% of young people reentering some type of out-of-home placement, including other systems that serve children (e.g. juvenile justice) after a reunification with family of origin [4,7-11].

The literature related to re-entry into out-of-home placement after reunification have historically had a clinical focus rather than a policy focus including exploring the protective and risk factors associated with a parent and children [12-14]. Studies that examine the correlates of re-entry generally explore the characteristics of children [9,10,12-16] but there remains research gaps including variation in re-entry policies, practices and the use of pre- and post permanency services for preventing re-entry both federally and by state.

A strategy that several states use to prevent re-entry is trial home visits (THV). THV are a period of time where a child is in the custody of the child welfare agency but placed in the family home— presumptively with supervision from child welfare services [9,17]. As state policies and practices vary THV go by many terms including trial visits home, trial return home, or trial reunification visits. Although federal policy does not require states to use THV, several states and jurisdictions within states have policies for their use. As states and jurisdictions create and implement THV policies, the lack of examination about this strategy is a gap that needs to be addressed.

There were three studies found in the literature reviewed that explored the use of THV. Studies examined showed that when children were placed in a THV their odds of re-entry were lower (OR=0.70) than children who were not placed in a THV (Shaw, 2015). Shaw (2020) found that use of THV reduced re-entry (OR=0.43) when compared with children who did not have THV as a placement (Shaw, 2020). Re-entries were also significantly lower for children who reunified with a THV compared to those not receiving THV [18].

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) provides funding for THV for states to use this loosely defined service mechanism to reunify families. These funds are time limited for up to six months but may encourage state agencies to reunify families and provide support for reunification during that time period. Such funds are provided through Title IV-E (45 CFR 1356.21€, 2023) and are considered foster care maintenance payment. There is no specificity about how many visits by child welfare professionals are required per week or what other strategies are needed to see if the “trial” is safely completed. Given this, exploring THV as a policy mechanism that can reunify families is critical. If there is evidence that THV shows promise this calls for next steps in creating mechanisms to test the efficacy of broader implementation of THV.

The Research Approach

This study provides an overview of the research, use and policies surrounding THV for practitioners, policy makers, and scholars interested in addressing re-entry focusing on the use of THV. We merge information from several sources for the purposes of this study. Sources of information included: (1) data extracted from the Children’s Bureau Outcomes by state report, specifically, outcome 3 (Exits from foster care) and 4.2 (Reentries into foster care); (2) a review of state report’s from the Child and Family Services Review (CFSR) Round 3 (Safety Outcome Item 2A: Services to Family to Protect Child(ren) in the Home and Prevent Removal or Re Entry Into Foster Care); (3) a review of the Title IV-E Prevention Service Clearinghouse (Find a Program or Service) (https://preventionservices.acf.hhs.gov/program); (4) a review of each state’s policy website and the Child Welfare Information Gateway (State Statutes Search) (https://www.childwelfare.gov/topics/systemwide/ laws-policies/state) [19] and an examination of State Child Abuse and Neglect (SCAN) Policies Database for mentions of THV and re-entry; (5) a review of state CFSR Round 3 Program Improvement Plan (PIP) and State Assessment (CFSR Round 3); and (6) a review of state Title IV-E Prevention Program Five Year Plan for mention of THV use and a goal of addressing re-entry. Information from each of these sources is synthesized for this endeavor to provide a national scan of the use of THV and re-entry outcomes. The aims of this work after to

(1) document the extent to which THV are being utilized across the United States.

(2) quantify the use of THV across the country, and

(3) provide guidance for child welfare stakeholders to access available information about re-entry by state.

Methods

Data Sources and Measures

The authors collected and synthesized data from multiple sources to meet the aims of this study in examining the use of THV and other re-entry prevention mechanisms in the United States. Sources include state policy sources, the State Child Abuse and Neglect (SCAN) Policies Database, Child and Family Services Review (CFSR) Round 3 reports, and the Children’s Bureau Outcomes. Each source is described in more detail below. The information from each source was evaluated for the named use of THV or the presence of information related to the use of THV. The sources were combined to develop a variable coded as ‘No = states not using THV or states with no evidence of using THV’ and ‘Yes = states have evidence or any indication of using THV’.

Sources of Evidence of Trial Home Visit Policies and Practices

The research team conducted a review of state policy resources to more closely examine the scope of THV use across the U.S. The initial search was conducted in July of 2023 and replicated in March of 2025.

The State Child Abuse and Neglect (SCAN). First, the research team reviewed the Explore Data by State section of The State Child Abuse and Neglect (SCAN) Policies Database at https://www. scanpoliciesdatabase.com/explore-data (2021). Each of the 50 states and two jurisdictions (Washington, D.C. and Puerto Rico) was assessed for the domain in home services post reunification and if present we recorded them as evidence of post-reunification services.

State Policies. Following the review of the policies available on SCAN, the research team reviewed state reunification policies through the Child Welfare Information Gateway State Statutes Search option [19]. Each state and territory’s website were cross referenced from the link provided through the Child Welfare Information Gateway (https://www.childwelfare.gov/topics/systemwide/laws-policies/ state/) [19]. If a state included use of a trial home visit by any name, they were coded as a 1 for use of THV.

Title IV-E Prevention Services Clearinghouse. Next we reviewed the Title IV-E Prevention Services Clearinghouse (Find a Program or Service) to examine each state’s prevention services plan (https:// preventionservices.acf.hhs.gov/program) [20]. We replicated our search terms (trial, THV, home visit, and reunification) and coded each state that mentioned the use of THV as 1.

Child and Family Services Review Round 3 Program Improvement Plans and State Assessments. Finally, the Child and Family Services Review (CFSR) Round 3 reports State Assessments and Program Improvement Plans (PIPs) were reviewed. We search for the terms trial, THV, home visit, and reunification (CFSR, 2019). If any of the reports included the use of THV the corresponding state was marked 1 for use of THV.

Using this methodology to explore state use of THV, nationally, a total of 38 states and District of Columbia states had indication of using THV, and 12 states and Puerto Rico did not have any evidence of using THV.

Re-entry Rates

Re-entry rates are included in the Office of the Administration for Children and Families (ACF) Children’s Bureau yearly Child Welfare Outcomes Report Data. Reports are for public use. The report includes outcomes for children and youth in out-of-home placement including removal rates, re-entry rates and exit rates. Re-entry is reported at the before and after 12 months’ time periods (https://cwoutcomes.acf.hhs.gov/cwodatasite/fourTwo/index) [21].

Re-entry rates within 12 months

Re-entry rates were examined for the year 2020 (This date was chosen because it was the last full year of data before COVID-19 markedly changed the way home visiting, of any sort, was conducted). We used Outcome 4.2 (Reentries into foster care) for re-entries within 12 months for the 50 states and Puerto Rico and Washington, D.C. One state, Maryland, was not available publicly due to disqualified reporting. The research team used raw percentage data.

Re-entry rates after 12 months. To examine re-entry rates after 12 months, we used the ACF, Children’s Bureau Outcome 4.2 (Reentries into foster care). Raw percentages were used. Again, we chose 2020 for the year of evaluation.

Combined re-entry rate. To create a year 2020 combined re-entry rate, we merged the raw percentage of re-entries at within 12 months and after 12 months. Data was extracted from the same Outcome 4.2 (Reentries into foster care) from the ACF Children’s Bureau website.

Reunification

Reunification outcomes were also collected from the ACF Children’s Bureau website. Using the year 2020, we collected data from Outcome 3 (Exit of children from foster care) using ‘exits by discharge type,’ to include children and youth who returned home through reunification (https://cwoutcomes.acf.hhs.gov/cwodatasite/threeOne/index).

Child and Family Services Review Ratings

The Child and Family Services Review (CFSR) is a multi-phase process that ensures states have met requirements of conformity as determined by the ACF and Families Children’s Bureau [20,21]. The CFSR process starts with a voluntary Statewide Self-Assessment that allows states to report on their own progress. Next is a mandatory on-site assessment by a team of federal and state employees [20]. Finally, states that are not considered in compliance with conformity requirements are required to complete a Program Improvement Plan (PIP) [22,23]. The most recent CFSR reporting is from Round 3 and includes years 2015-2018 (2019).

CFSR rating of services to prevent removal or re-entry. In the CFSR Round 3, services aimed at preventing removal or re- entry were assessed under Safety Outcome 2—“Children are safely maintained in their homes whenever possible and appropriate”— specifically Item 2A, which focuses on services provided to families to protect children and prevent removal or re-entry into foster care. Each CFSR report evaluated the performance percentage for 50 states, excluding Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia. States are required to review a minimum sample of 65 cases, with at least 40 involving intact families and 25 involving children who have been removed and placed in out-of-home care. While some states adhere to the minimum sample size, others—typically those with larger populations—review a larger number of cases. For this analysis, the authors used the reported raw percentages from these case reviews and noted whether each state identified this outcome as a strength or as an area needing improvement in the policy review and outcomes list.

Urbanicity

Urbanicity data was extracted from the 2010 Decennial Census, U.S. Census Bureau, presented by Iowa Stata University Iowa Community Indicators Program website (https://www.icip.iastate. edu/tables/population/urban-pct-states). Urbanicity, as used in this study, represents the percentage of a state’s population living in urban areas. States with less than 65% of their population in urban areas are considered rural, those between 65% and 85% are mid-sized, and those between 86% and 100% are classified as urban. In our analysis, we treated urbanicity as a continuous percentage variable.

Data Presentation

All data were extracted and organized using Stata version 19.0. Descriptive analyses were performed to summarize the mean, standard deviation, median, and range for all study variables.

Results

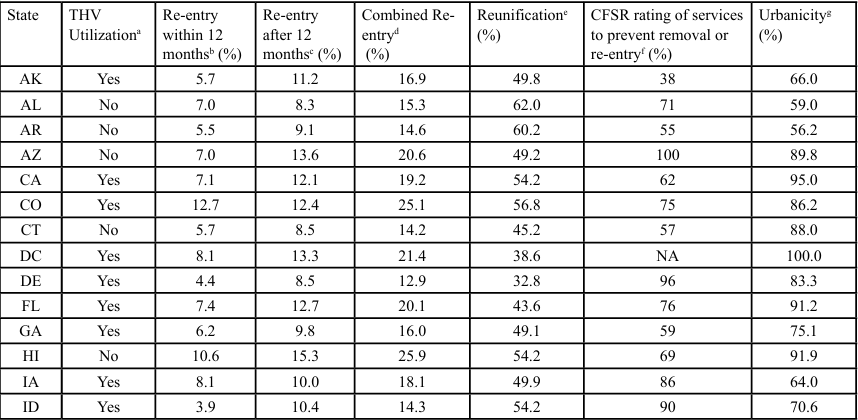

Table 1 shows the indication of THV utilization and re-entry characteristics of the states. Overall, 38 states and the District of Columbia reported incorporating THV in their practices, whereas 12 states and Puerto Rico made no reference to THV in their policy documents. The rate of re-entry within 12 months varied between 2.7% and 16.8%, with an average of 7.85% (SD = 3.25), and a median of 7.1%. For Re-entry after more than 12 months, percentages ranged from 3.0% to 16.9%, with a mean of 11.18% (SD = 3.05) and a median of 11.2%. When combined, overall re-entry percentages spanned from 5.7% to 29.4%, with a mean of 19.03% (SD = 5.29), and a median of 19.0%.

The percentages of children who reunified with their families ranged from 32.8 to 85.9% with a mean percentage of 54.62 (SD = 9.43), and a median of 54.2%. State’s CFSR rating of Safety Outcome 2 Item 2A: Services to Family to Protect Child(ren) in the Home and Prevent Removal or Re-Entry into Foster Care ranged from 8 to 100%, with a mean of 64.74 (SD = 19.19), and a median of 66.5%. The urbanicity percentage of states ranged from 38.7 to 100%, with a mean of 74.11% (SD = 14.89) and a median of 74.2%.

Discussion

This paper combined multiple sources to document the use of THV across the US and provide guidance for child welfare practitioners, and policy makers about where to find publicly available policy sources for THV. We have provided a broad overview of state policies and have described state re-entry outcomes and their possible association with THV use in detail.

Regarding use of THV, we have learned that families who are in this type of living situation are tracked only in AFCARS data and not in other publicly available data sources. For example, the Children’s Bureau Outcomes report many other permanency outcomes but not THV. Given that THV can be a critical point of time there is a need to understand the outcomes of that time period and how that is associated with re-entry in publicly available data. Given the inconsistency in how THVs are used (e.g. with states reporting use anywhere from a month to six months) and re-entry rates only tracked at the two time periods it is difficult to match rates with THV use. Further, although states create their own policies and practices under federal guidance, a more consistent definition of THV nationally would also be helpful for policymakers and practitioners who implement THV across the country.

Improving the precision of re-entry analysis would benefit from faster access to longitudinal data from the Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS). The linking of the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS) into a single longitudinal file with AFCARS has recently provided an avenue for researchers to explore re-entry outcomes more in depth. This integration—long overdue—has been achieved by a team of child welfare researchers from Washington University and the Kempe Center at the University of Colorado. Scholarly work using these linked datasets, such as studies by Jones et al. [24], Kim et al. [25], and Barth et al. [26] (under review), is beginning to emerge. These data need to be made broadly available and used by the federal government to support quality assurance efforts with states and to inform federal policymaking.

Improved reporting would also extend to include THV in the CFSR reporting. Currently, the state sampling frames in CFSR round 4 can include THV in either the Foster Care frame and/or the In-Home Services sampling frame under specific circumstances [27], but this is likely to produce a small sample size that will not be comparable across states. The CFSR is re-introducing re-entry outcomes to the Round 4 reporting period, but including THV would enable far greater understanding of re-entry outcomes. We recommend future replication of our work to examine the CFSR Round 4 when it becomes available.

Our findings also revealed that THV policies vary considerably across states and jurisdictions. Additional research comparing the length of time children spend in THV with the timing and circumstances of their re-entry could help policymakers and child welfare agencies refine how this tool is implemented. For instance, some jurisdictions limit THV to 30 days, while others allow up to 90 days or even six months. Future studies should also examine the provision of services aimed at preventing re-entry during the THV period. In our review of the California Evidence Based Clearinghouse and of the Title IV-E Prevention Services Clearinghouse, we found several interventions available for states to use to prevent re-entry and promote placement stability after reunification. Given the substantial resources states have been provided for investing in evidence-based services through Title IV-E Prevention Plans under the Family First Prevention Services Act (P.L. 115-123), it is critical to further scholarship about how those services are used during a THV. Such research would help policymakers assess how funding is used for THV under the Title IVE entitlement and how non-profit or non- governmental organizations (NGO) providers can provide such services. Finally, evaluation of THV would also require the inclusion of perceptions and experiences of those with lived experience. Findings from one study that include perspectives of families show that often families find services inadequate during reunification [28]. Another recent study replicates an earlier finding that families generally find that the child welfare professionals that they engage with are respectful and responsive but the services they get sent to are not a good fit for them [29,30]. Child welfare workers’ perspectives are also necessary due to their impact on how services are accessed during the reunification process.

Limitations

Given the design of this study as an exploratory piece to determine all that was known about re-entry and the use of THV throughout the United States, this effort has some limitations. Efforts made to reduce re-entries are not adequately described in the public record. The lack of clear language and conceptualization about THV is especially notable. For example, state policies identify THV under a variety of names, including commonly used phrases like trial reunification, trial reunification visits, trial placement visits, trial return home, and reunification visits. To determine which states employed this intervention the authors had to search for a variety of policy sources for different phrases and quite likely still missed information about states’ use of THV. This lack of clarity also extended to policy reporting as different websites reported usage of some kind of THV and other policy sources did not. For example, one state did not have a policy available about the use of THV but made mention of their use in the CFSR Round 3 Program Improvement Plan.

The data used for the urbanicity variable is also a limitation. More recent data may or may have changed the urbanicity status of some states. It may also have been more effective to use county-level data, which has been shown to have strong associations with many child welfare dynamics, including reunifications [31].

Conclusion

The authors synthesized several sources to create the clearest possible picture of trial home visit use and re-entry outcomes in the United States. Results show that there are many publicly available sources for understanding re-entry and trial home visits but there are many limitations in reporting. This study makes recommendations to improve reporting about re-entry outcomes through child welfare practitioners and policy makers. Clarity about what funds can be used and should be used to expand the use of trial home visits is needed—at the local level this would also include clarity about what the practices should be in place to manage this expansion of care. As federal and state foster care policies continue to change to reduce placements into foster care, but re-entry rates remain high, it is more critical than ever that re-entry moves to the forefront of policy-making activity.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

Child Welfare Information Gateway (2020). Reasonable efforts to preserve or reunify families and achieve permanency for children. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Children’s Bureau. View

McGrath-Lone, L., Dearden, L., Harron, K., Nasim, B., & Gilbert, R. (2017). Factors associated with re-entry to out-of home care among children in England. Child Abuse & Neglect, 63, 73–83. View

Shaw, T. V. (2021). Trial home visits and foster care reentry. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 15(1), 6–21. View

Wulczyn, F., Parolini, A., Schmits, F., Magruder, J., & Webster, D. (2020). Returning to foster care: Age and other risk factors. Children and Youth Services Review, 116, 105166. View

LaBrenz, C. A., Panisch, L. S., Liu, C., Fong, R., & Franklin, C. (2020). Reunifying successfully: A systematic review of interventions to reduce child welfare recidivism. Research on Social Work Practice, 30(8), 832–845. View

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Children’s Bureau. (2019). Child and Family Services Review Round 3 2015-2018. (December 2022). Retrieved December 7th, 2022, from https://www.acf. hhs.gov/cb/monitoring/child-family-services-reviews/round3 View

Lee, S., Jonson-Reid, M., & Drake, B. (2012). Foster care re entry: Exploring the role of foster care characteristics, in-home child welfare services and cross-sector services. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(9), 1825–1833. View

Shaw, T.V. (2006). Reentry into the foster care system after reunification. Children and Youth Services Review, 28, 1375 1390.View

Shaw, T.V. & Barth, R.P. (2021). Toward an evidence based practice model to increasing post-permanency outcomes. A report produced for the Annie E. Casey Foundation.

Shipe, S. L., Shaw, T. V., Betsinger, S., & Farrell, J. L. (2017). Expanding the conceptualization of re-entry: The inter-play between child welfare and juvenile services. Children and Youth Services Review, 79, 256–262. View

Wulczyn, F., Chen, L., & Hislop, K.B. (2007). Foster care dynamics 2000–2005: A report from the Multistate Foster Care Data Archive. Chicago: Chapin Hall Center for Children at the University of Chicago View

Davidson, R. D., Tomlinson, C. S., Beck, C. J., & Bowen, A. M. (2019). The revolving door of families in the child welfare system: Risk and protective factors associated with families returning. Children and Youth Services Review, 100, 468–479. View

LaBrenz, C. A., Fong, R., & Cubbin, C. (2020). The road to reunification: Family- and state system-factors associated with successful reunification for children ages zero-to-five. Child Abuse & Neglect, 99, 104252. View

Semanchin Jones, A., & LaLiberte, T. (2017). Risk and protective factors of foster care reentry: an examination of the literature. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 11(4/5), 516–545. View

Ahn, H., Shaw, T., Kim, J., Williams, K., Moeller, E., & Chung, Y. (2025). Caseworker visitation after reunification and children’s reentry into foster care: A survival analysis. Child Maltreatment, 30(1). View

Goering, E. S., & Shaw, T. V. (2017). Foster Care Reentry: A survival analysis assessing differences across permanency type. Child Abuse & Neglect, 68, 36–43. View

Child Welfare Information Gateway. (2016). Reunification: Bringing your children home from foster care. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau. View

Jedwab, M., & Shaw, T. V. (2017). Predictors of reentry into the foster care system: Comparison of children with and without previous removal experience. Children and Youth Services Review, 82, 177–184. View

Child Welfare Information Gateway. State Statute Search. Retrieved from https://www.childwelfare.gov/topics/systemwide/laws-policies/state/ View

State Child Abuse & Neglect Policies Database (2021). Child Welfare Responses. View

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Children’s Bureau. (2021). Child Welfare Outcomes Data. Outcome 4.2: Reentries into Foster Care. Retrieved December7th, 2022, from https://cwoutcomes. acf.hhs.gov/cwodatasite/fourTwo/index. View

Ahn, H., DeLisle, D., & Conway, D. (2022). Child and family services review (CFSR) and child welfare outcomes in the United States. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 16(5), 679–703. View

Milner, J., Mitchell, L., & Hornsby, W. (2001). The child and family service review: a framework for changing practice. Journal of Family Social Work, 6(4), 5–18. View

Jones, D., Orsi-Hunt, R., Kim, H., Jonson-Reid, M., & Drake, B. (2024). Life-course trajectories of children through the U. S foster care system. Child abuse & neglect : The international journal., 153, 106837. View

Kim, H., Orsi-Hunt, R., Drake, B., Hollinshead, D., Fluke, J., Jones, D., Wilson, R., Jonson-Reid, M., & Ahn, E. (2025). Benefits of longitudinally linked national records of child maltreatment report and foster care. Child abuse & neglect : the international journal., 161, 107262. View

Barth, R.P. Yu, M.H., Jones, D., Lee, H., Drake, B. (under resubmission review). Re-entry of adolescents into out-of-home care in the USA. Child Maltreatment

Child and Family Services Reviews (2025). Procedures Manual. Available from: CFSR Round 4 Procedures Manual | CFSR Information Portal Accessed: June 24, 2025

Bai, R., Collins, C., Fischer, R., & Crampton, D. (2022). Factors leading to foster care reentry: experiences of housing unstable families. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 18(1), 1–20. View

Chapman, M. V., Gibbons, C. B., Barth, R. P., & McCrae, J. S. (2003). Parental views of in-home services: What predicts satisfaction with child welfare workers? Child Welfare, 82(5), 571-596.

://000185301300005 View Barth, R. P., & Xu, Y. (2025). Satisfaction with child welfare workers and services: reports from mothers receiving child welfare services. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 1-17. View

Wulczyn, F., Chen, L., & Courtney, M. (2011). Family reunification in a social structural context [Article]. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(3), 424-430. View