Journal of Social Work and Welfare Policy Volume 3 (2025), Article ID: JSWWP-163

https://doi.org/10.33790/jswwp1100163Research Article

Filtering Evidence: Politics, Communication, and Resource Pressures in Policy Contexts

Tracey Barnett McElwee*, PhD, LMSW, Laura Danforth, PhD, LCSW, Christine Bailey, BS, CIT, N. Myton El, BSW, Ambria Lancaster, BA PTW, Kya Moore, BSN, Sophie Nowell, BS, Brooklyn Russell, BA, Kasey Smith, BSW, Cara Teague, BS, Alexandra Wallace, BS, LaDejhia Wright, BSW, Olivia Wright, BA, and Missy Ziemski, BSW

*School of Social Work, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, 2801 S. University Ave, Little Rock, AR 72204, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Tracey Barnett McElwee, PhD, LMSW, Associate Professor and Gerontology Program Coordinator, School of Social Work, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, 2801 S. University Ave, Little Rock, AR 72204, United States.

Received date: 30th July, 2025

Accepted date: 29th September, 2025

Published date: 03rd October, 2025

Citation: McElwee, T. B., Danforth, L., Bailey, C., Myton El, N., Lancaster, A., Moore, K., Nowell, S., Russell, B., Smith, K., Teague, C., Wallace, A., Wright, L., Wright, O., & Ziemski, M., (2025). Filtering Evidence: Politics, Communication, and Resource Pressures in Policy Contexts. J Soci Work Welf Policy, 3(2): 163.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Policymakers and administrators frequently encounter structural barriers such as rigid policies, poor interagency coordination, and fragmented services that limit their ability to respond effectively. This study adapted the well-established Qualitative Interpretive Meta-Synthesis (QIMS) method to examine how communities, policymakers, and practitioners utilize, resist, or reinterpret research evidence within social welfare policymaking. Through the collaborative efforts of 12 social work graduate students and faculty, the team applied constant comparative analysis and triangulation to identify three overarching themes: (1) Evidence Is Filtered Through Politics, Power, and Context, (2) Intermediaries and Trusted Brokers Are Key, and (3) Evidence Must Compete with Funding and Resource Pressures. These themes reveal that while evidence can influence policymakers, several barriers often limit its impact such as deeply held political beliefs, budget limitations, and lack of engagement from government agencies. Despite these obstacles, participants highlighted that evidence becomes more relevant when it is communicated strategically, shared within strong relationships, and aligned with the needs of local citizens. Servings as connectors between data, policy, and practice, Social workers can play a vital role by promoting evidence-based policies, and cultivating partnerships between municipal governments to strengthen public services.

Keywords: Policy Advocacy, Research Evidence, Policy Development, QIMS, Social Work

Introduction

The application of evidence-based research in policy making is universally understood to be necessary and problematic. The use of research evidence in policymaking is widely acknowledged as both essential and difficult [1,2]. For example, government officials have reported difficulties when attempting to translate research into their policy making choices. For instance, policymakers often struggle to apply research findings directly in their decision-making processes [2], and scholars frequently document the complexities of integrating research evidence into policy change [3]. Often in close proximity to the community’s needs, Municipal governments have a strong preference for locally relevant research [1,4]. However, they are frequently controlled by political pressures, as political processes can have a stronger influence than research and evidence may be used to serve a political agenda [4,5]. These local governments also face resource limitations, such as insufficient time for staff to gather and interpret complex data [1,4]. Despite repeated calls for evidenceinformed policy, research often fails to infiltrate municipal decisionmaking processes in consistent and transformative ways [2-4]. This can lead to a reliance on non-peer-reviewed reports, anecdotes, and an over reliance on internally produced descriptive data rather than independent assessments [5].

Literature Review

Prior Research on Evidence Utilization and Tensions

Qualitative research has consistently underscored the tensions involved in integrating research into policy making [1,3-5]. Although policy makers government officials and social work practitioners engage with research evidence based, its use is rarely straight forward [4]. Research evidence typically shapes how issues are framed, rather than serving solely as an instrumental role to directly shape decisions [4]. It may also be deployed strategically, when used to justify predetermined approaches or strengthen political buy-in [4]. For instance, in Allen et al. [3] found that policymakers across three U.S. cities employed evidence both instrumentally, to advance syringe exchange programs, and symbolically, to legitimize prior commitments which often prompted pushback.

Similar studies have echoed these themes of complexity, as Nelson et al. discovered that policymakers and practitioners frequently concealed doubts about empirical evidence and its transferability to their unique community settings [4]. They placed more weight on "practical, real-life, or pragmatic" evidence, which included lived experience, place-based research, and jurisdiction-specific findingslocal research, local data, and personal experience [4]. This echoes the finding that research is most significant when it is relevant to a user's specific context [4]. The communication gap between researchers and policymakers is a key reason for this. Friese and Bogenschneider [1] found in their study of family research, researchers and policy makers often operate in different cultures, which can lead to misunderstandings because they have different goals, information needs, values, and even use different language. These authors emphasized the importance of developing collaborative relationships with policymakers rather than simply disseminating research [1].

The Influence of Financial and Organizational Pressures on Evidence Use

At the same time, the use of evidence is often shaped by financial and organizational pressures [2,6]. Wye et aland colleagues discovered that English healthcare commissioners, while encouraged to adoptdirected toward "evidence-based research policymaking," often made pragmatic choices of evidence, by prioritizing favoring best practice guidelines guidance, perspectives from service users and clinicians clinicians' and users' views, and local data over academic research [2]. When research was unclear or unfavorable results yielded little to no value, the findings failed to guide decisions on funding or services [2]. If research evidence ever clashed with budget requirements or other priorities, commissioners frequently adapted or dismissed it altogether [2].

Population health indicesWhile population health rankings are intended to ignite evidence research-informed health policymaking, Purtle and colleagues found that they are used in various ways depending on organizational capacity institutional resources, county political orientation ideology, and county status rank [6]. These rankings were usedserved instrumental purposes ly to guide inform internal planning, to educate the public conceptually to educate the public, and politically to advance organizational agendas [6]. This demonstrates that even widely disseminated data can be strategically amplified or downplayed based on fiscal and political priorities, and to advance organizational goals [6].

Statement of Purpose

Although prior studies have examined evidence use, important gaps remain in understanding how research is applied within municipal policymaking contexts. Studies often rely on self-reports by policymakers, which may not always reflect actual practices [2]. Further empirical investigation is required to observe and monitor the process by which information travels through various systems [2]. Future research could explore how these different forms of evidence are utilized and their implications. There is also an ongoing need for research that can be easily understood and utilized by policymakers, therefore bridging the gap between scientific verbiage and practical application [3].

The purpose of this qualitative interpretive meta-synthesis (QIMS) aims to is to examine how communities, policymakers, and practitioners utilize, resist, or reinterpret research evidence within municipal social welfare policymaking. By synthesizing findings from seven qualitative studies, this research seeks to identify common patterns in the political usage of evidence; highlight the influence of funding pressures and highlight the contextual factors that shape how evidence is translated or sidelined within decision-making. The QIMS methodology proved ideal for this research because it allowed for comparison across diverse studies while highlighting the perspectives of policymakers and practitioners and offering a deeper understanding of the complex multifaceted relationship among between research, politics, and practice in municipal governance.

Method

Qualitative Interpretive Meta-Synthesis (QIMS) is a methodological approach that integrates themes from qualitative studies and translates them into a cohesive, in depth insight into a specific understanding of a given phenomenon [7]. Although qualitative meta-synthesis has long been applied in fields such as nursing and social work, Aguirre and Bolton [7] specifically refined the QIMS approach for social work policy, practice, and research. QIMS addresses the small sample size limitation of qualitative studies by pooling participants across multiple studies. This method yields a combined sample size large enough to be comparable to those used in quantitative research. The QIMS process typically entails four interconnected stages: (1) instrumentation, (2) literature sampling, (3) data extraction, and (4) translating findings into an integrated understanding of the topic being studied synergistic interpretation of the phenomenon under study.

Instrumentation

In qualitative research, the researcher is often considered the primary instrument of inquiry, thus making it essential to acknowledge potential biases and establish credibility. This study was conducted by a team of 12 Master of Social Work (MSW) graduate students enrolled in a research methods course, researchers under the guidance of the lead author who was also the course instructor and with input from community experts and partners. Given the project's time sensitive nature, it was completed within a single 15- week semester defined project timeline. The lead author acted as course instructor acted as project manager and main contact person, adapting the QIMS methodology for collaborative implementation. by restructuring the MSW research methods course to incorporate this hands-on project. The lead author also designed the study, taught and adapted the QIMS methodology for rapid analysis in a collaborative research settingand real-world application for a 15 week semester, and provided consistent oversight and coordinator throughout the research process. assessed student work, and provided consistent oversight and coordination throughout all phases of the research process.

Since this study analyzed exclusively secondary data from existing qualitative research and one policy report, no additional human participants were involved, thus eliminating the need for IRB approval. We acknowledge the potential for bias arising from the instructor's dual position as both course faculty (responsible for student evaluation) and research collaborator. To mitigate this concern, we implemented several protective measures including defined team responsibilities, collaborative decision-making processes, regular reflexivity conversations, and cross-team peer evaluation. These strategies promoted transparency, equity, and methodological rigor throughout both educational and research activities.

The lead author has published extensively using the QIMS method, [8-14] and therefore adapted the approach to balance rigorous analysis with student learning to be accomplished within a 15 week semester. Using an adapted version of QIMS, the team collaborated to ensure transparency and credibility. Students assumed defined and interchangeable roles which included literature searching, article screening, quote extraction, coding, theme development, and manuscript preparation. These activities were supported by this was supported by weekly discussions, peer review, and faculty oversight to ensure rigor and transparency.

In traditional QIMS manuscripts, each author typically provides an individual credibility statement. However, in this adapted version, the authors’ combined credibility is reported collectively. Drawing from fields including social work, psychology, sociology, criminology, nursing, and addiction studies, the research team's interdisciplinary composition was important to the project's success. Their combined background knowledge and experience encompassed mental health, housing access, trauma, addiction, human trafficking, and legal advocacy. Therefore, producing perspectives for a comprehensive interpretive synthesis. While some members had worked directly with unhoused populations, others offered insights from policy development and child welfare practice. This breadth of experience strengthened the team's self-reflection and anchored the research in both practical application and social work's core values.

Sampling and Study Selection

A purposive sampling strategy was employed to identify qualitative studies examining municipal coordination and homelessness. Database searches were conducted across Google Scholar, Web of Science, Academic Search Ultimate, Communication and Mass Media, Education and Research Complete, ERIC, Sociology Database, and PsycINFO between January -April 2025. Boolean operators and search combinations were developed to capture a wide range of qualitative research on homelessness and municipal coordination. Core terms included homelessness OR unhoused individuals OR housing insecurity, combined with municipal coordination OR interagency collaboration OR cross-sector partnerships. To ensure focus on qualitative studies, terms such as lived experiences, personal narratives, focus groups, interviews, phenomenology, grounded theory, and case studies were included. Example search strings included: ("unhoused individuals" OR "homeless" OR "housing insecure populations") AND ("municipal coordination" OR "interagency collaboration" OR "cross-sector partnerships") AND ("qualitative research" OR "lived experiences" OR "personal narratives").

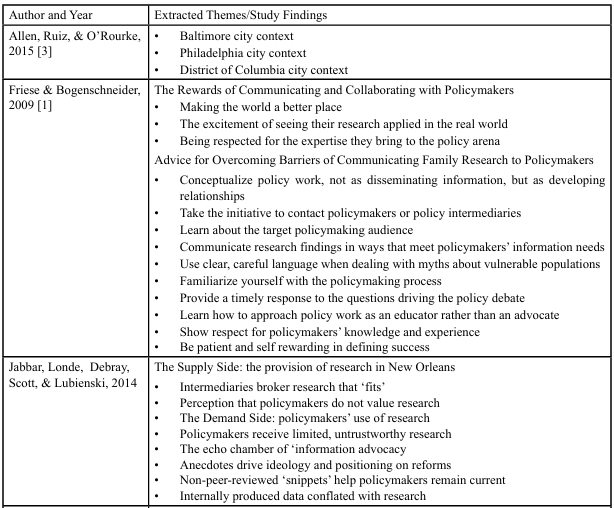

Studies were eligible if they (a) employed qualitative methods, (b) examined homelessness or municipal-level service coordination, and (c) were peer-reviewed. Studies were excluded if they were nonqualitative, did not address, municipal systems and/or homelessness. Despite an extensive search, no peer-reviewed qualitative studies were found that directly addressed homelessness within municipal coordination systems. Given this gap, the sampling frame was broadened to include qualitative studies of evidence utilization and decision-making in municipal and policy contexts more generally. The initial search identified 394 potentially relevant studies. After removing 85 studies during the title review, many of which were duplicates, 309 articles remained for abstract screening. Of these, 250 were excluded for not meeting failing to meet inclusion criteria, primarily most often because they employed quantitative methods or did not directly address the topic of interest. Ultimately, seven qualitative studies met the final inclusion criteria, representing the perspectives of 254 state and local policy makers, municipal and district leaders, intermediary organizations, health and public policy stakeholders, researchers and policy advocates and media and community representatives across the United States. The sampling process is illustrated in the study’s quorum chart (Figure 1), and a detailed summary of each study is presented in Table 1.

From the final set of studies, direct participant quotes and author interpretations were extracted into a shared spreadsheet. See Table 2. The research team engaged in line-by-line coding, generated short descriptive codes (2–5 words) that captured the essence of participant experiences. Codes were then compared across studies, clustered into categories, and translated into broader interpretive themes. This process highlighted both convergences and divergences across studies and allowed for the emergence of three primary themes: (1) Evidence Is Filtered Through Politics, Power, and Context, (2) Intermediaries and Trusted Brokers Are Key, and (3) Evidence Must Compete with Funding and Resource Pressures.

Analysis and Triangulation

Constant comparative analysis was employed to interpret the meaning of participants’ experiences across diverse contexts. Triangulation was embedded throughout the process: (a) data triangulation was achieved by synthesizing across multiple qualitative studies; (b) investigator triangulation was ensured through collaborative coding, peer review, and team-based theme development; and (c) methodological triangulation was enhanced by incorporating multiple qualitative traditions represented in the included studies (e.g., phenomenology, grounded theory, narrative inquiry). Reflexive memos and team debriefs were maintained throughout the project to enhance transparency and rigor. This analysis revealed three themes that together illustrate how municipal and public-sector decision-makers both utilize and encounter challenges with research evidence. The findings that follow provide details for each theme through representative participant quotes and analytical interpretation.

Results

Theme 1: Evidence Is Filtered Through Politics, Power, and Context

Throughout all seven studies, policymakers and administrators seldom accepted evidence without question. Instead, they processed findings through their political objectives, ingrained perspectives, and local contexts. Evidence played multiple roles: functioning as a practical decision-making tool, offering symbolic validation, or being deliberately ignored or reinterpreted to align with existing plans. From the Allen study, the city of Baltimore, Maryland provides a clear example, where stakeholders reported using research evidence instrumentally to inform syringe exchange program (SEP) policy development. Advocates emphasized, “I think what that did was let the science drive the policy discussion rather than a lot of fear mongering” [3]. Champions with medical and public health backgrounds leveraged empirical data to counter opponents’ fears that SEPs would increase drug use or crime.

In contrast, Philadelphia’s context revealed a more symbolic and conceptual use of research. Activists created an underground SEP and later justified it with published evidence, noting, “So we had read a paper on it and we circulated it among the leadership, and we liked the methodology they had in New Haven so we said alright, we can give this a try” [3]. Here, research served less as a driver of change and more as a legitimizing force for decisions activists had already made. The District of Columbia case demonstrated how evidence could be dismissed or manipulated to reinforce existing political stances. SEP supporters described presenting comprehensive research data, but noted that "…because the evidence was, whether you quoted from scientific journals. . . and . . . statistical evidence, from what was happening across the United States, none of it mattered" to their opponents. These opponents would sometimes selectively quote research findings out of context to justify their continued resistance to the program [3]. Similarly, Jabbar et al. [5] found that in New Orleans education reform, intermediary organizations often tailored research to fit pre-existing agendas, with one representative admitted by saying, “I would like to say we look at research and then we go to the legislature, but we don’t. We see what’s out there, see what fits, [and] use it to back up … what we can do” (p. 1017). Policymakers themselves noted they often relied more on anecdotes or ideological cues than systematic research, with one Louisiana legislator stating bluntly, “People are just kind of like political hacks. They’re not interested in what solves the problem—they’re interested in what looks like it’s solving the problem” [5]. Lastly, from a representative of the Louisiana’s Association of Educators, a representative described how legislators typically favor brief, digestible messages rather than comprehensive evidence: "They don't want to be educated on an issue. They want us to distill things down… in 2 or 3 minutes." This participant further observed that even when "tons of research to support" specific policy directions existed, lawmakers regularly dismissed the data in favor of ideological positions or political messaging [5]. This case demonstrates how evidence frequently becomes secondary to political convenience, with research appreciated more for its capacity to be transformed into compelling talking points than for its actual content. It reinforces the larger pattern that evidence utilization in policy development depends not just on research quality but on how politically useful its communication proves to be. Association of Educators said:

I find that in this work, more times than not, the people that we talk to, in particular legislative members, they don’t want to be educated on an issue. They want us to distill things down. Matter of fact, one legislator told me: you got to be able to say it in 2 or 3 minutes, you got to have all the data and everything. I said, do you know what you’re asking me to do is virtually impossible ... in many of the issues that we’re dealing with, there’s tons of research to support, in most instances, at least the proper direction going in ... But people ignore the research. They ignore the data. What they’re looking for is the quick ideological quip or they’re looking for something that is a political quip that they can just take and run with. In many instances, legislative members already have their minds made up because of either a political favor or because this is really not significant for them and somebody asked them to go a particular way and so they’ll do that [5].

Similar patterns appeared in health rankings research, where county leaders acknowledged manipulating data for political purposes. As one administrator admitted, “I use [the CH-Rankings] when it’s opportune to use it, and I ignore it when it’s opportune … It’s all in how you spin it” [6]. This selective use of data illustrates how evidence can be reshaped into a political tool rather than a neutral guide. Findings from Nelson et al. [4] further emphasized that political forces and leadership turnover often outweighed research itself. State legislators and district administrators reported that mandates or political directives often dictated practice regardless of evidence: “You have to deal with it when the governor says something, regardless of the budget” (p. 13). Others noted that while evidence might support certain reforms, “the reality is that sometimes, even given the best research or some research or some evidence, we may still ignore it” (p. 26).

Taken together, these findings highlight the complex interplay of politics, power, and context in shaping evidence use. Whether instrumental, symbolic, or selectively ignored, research evidence was rarely the sole driver of policy; rather, it functioned within broader political and organizational landscapes where competing interests, leadership turnover, and fiscal pressures were often equally or more influential.

Theme 2: Intermediaries and Trusted Brokers Are Key

Across the seven studies, policymakers consistently relied on intermediaries which are advocacy organizations, associations, trusted staff, and professional networks to translate and broker evidence. Rather than engaging directly with academic research, decision-makers frequently turned to individuals and organizations they perceived as credible, accessible, and aligned with their priorities. In New Orleans, intermediary organizations played a particularly powerful role in framing and disseminating evidence. Jabbar et al. [5] found that reform advocates strategically packaged information for policymakers and they acknowledged relying on this kind of selective brokering. They noted that they often accessed research through a “preferred list of brokers” rather than directly. A Louisiana Department of Education employee highlighted that information circulated via ongoing discussions with a "preferred list of brokers" instead of through official research pathways: "The education community here is so connected… we just talk to these folks constantly" [5]. This case illustrates that officials frequently depended on casual professional connections and reliable brokers instead of direct research access, supporting the pattern that messenger credibility typically carried more weight than the strength of the actual evidence. As one Louisiana Department of Education staffer explained,

“I wouldn’t say there are particular researchers or any specific organizations ... The [education] community here is so connected and always talking about whatever the latest issues are that through whatever channels we just are always talking about whatever happens to be most on the minds of most of the ed reformer folks around here…. Like all the people that you probably talk to, we talk to all of the time, like Neerav [Kingsland]. We just talk to these folks constantly. And Neerav is probably the one who researches more than all the rest of us. He’s always like, ‘maybe you should think about this” [5].

Similarly, Nelson et al. [4] reported that policymakers at federal, state, and local levels depended on professional associations and intermediaries to navigate overwhelming volumes of evidence. A National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) participant explained, “I have to go to the sources that I trust, because there is too much out there” (p. 27). Trusted networks helped filter evidence into usable, context-specific knowledge, by often carrying more weight than independent academic studies.

Friese and Bogenschneider [1] also highlighted intermediaries’ role in bridging the academic–policy divide. Researchers who had the most success in influencing policy did so by shifting from dissemination to relationship-building. As one explained, researchers who effectively influenced policy developed relationships that established them as reliable consultants. One participant noted that policymakers began contacting him "earlier in the process to help develop policy approaches," instead of only during emergencies (p. 8). These relationships positioned researchers themselves as trusted intermediaries, rather than as detached academics.

“… much more of a comfortable give-and-take. There is an assumption that we look at common problems, but from a very different perspective, and the challenge for both of us is to find the middle ground where we are mutually supportive of the other’s agenda. Because of the rapport he has established, one researcher with experience in 14 countries relayed that policymakers “come to [him] earlier in the process to help develop policy approaches” so he “can have input early on rather than the forest fires that you hit at the end.” (p. 8).

Other studies further reinforced the importance of intermediaries in ensuring research relevance and uptake. For example, Mosley [15] found nonprofit managers increasingly joined coalitions and cultivated ties with government administrators as a way to influence policy and maintain funding streams. One director summarized this relational approach: “Our government officials look to us as the experts and want to know from us what they should be doing and how they should be casting their votes. They're the people who hold the purse strings, that's the kind of thing they offer back to us” (p. 857). Taken together, these findings demonstrate that policymakers rarely use research in isolation. Instead, they rely on intermediaries to interpret, validate, and communicate evidence in accessible and politically salient ways. The credibility of the broker often mattered more than the content of the research itself.

Theme 3: Evidence Must Compete with Funding and Resource Pressures

Across all seven studies, the use of evidence was deeply entangled with economic realities. Policymakers and organizational leaders often weighed research findings against financial considerations, by using or sidelining evidence depending on whether it aligned with budgetary constraints, funding streams, or broader resource pressures.

In Mosley’s [15] study of nonprofit managers, advocacy was largely framed as a strategy for resource acquisition rather than policy change. Leaders of government funded organizations consistently described advocacy as “self-interest” tied to maintaining contracts: “The benefit—in terms of getting involved—is you're able to stay in the funding stream” [15]. Mosley [15] reported that governmentsupported nonprofits commonly viewed advocacy as necessary for maintaining organizational viability: "The benefit… is you're able to stay in the funding stream" (p. 853). Another organizational leader indicated they typically engaged in advocacy only when funding opportunities or service enhancement were in jeopardy (p. 854). One director reflected, “We would take an advocate role when our programs are either going to be negatively impacted or if we can expand the services that we offer through some kind of policy change. It's not quite as selfish as what it sounds like because we really believe that we do conduct best practices" (p. 854). This highlighted how organizational sustainability and client needs were often viewed as inseparable. Advocacy, in this sense, was institutionalized as a management tool to stabilize funding relationships rather than an independent pursuit of policy reform.

Similarly, budgetary and economic conditions shaped evidence use at the municipal and state levels. Nelson et al. [4] found that fiscal pressures often drove policy decisions more than data itself: “Sometimes fiscal realities and fiscal aspects are the biggest player” (ASCD, p. 12). Another participant stated:

Economics in our state is playing a big role, our new governor says that there are two towers—one is education and the other is economics—and one can’t exist without the other. Everything we do now is linked to economics (p. 12)

This viewpoint demonstrates how budgetary considerations emerged as the primary framework for evaluating policy choices. Despite the presence of supporting evidence, financial constraints defined the limits of what was considered politically viable, reinforcing the pattern that economic pressures routinely shaped the impact of research in local government settings.

Policymakers acknowledged that even strong evidence was frequently sidelined when it clashed with economic priorities: “Particularly in the last two or three years, you don’t do anything without realizing that property taxpayers are going to be impacted by anything and everything you do” (NCSL, p. 12). In these contexts, the availability or lack of funding acted as both a facilitator and barrier to evidence-informed change.

In the UK commissioning system, Wye et al. [2] observed how commissioners often bent evidence to fit statutory financial obligations. While evidence reviews sometimes showed that interventions were ineffective, commissioners still advanced them to balance financial plans. British commissioners confessed to adjusting evidence to comply with mandatory budgetary duties: "We've still got a statutory responsibility to deliver a balanced plan, and if I take those savings out they need to come from somewhere else" [2]. In this setting, evidence was subordinated to the imperative of presenting a “viable financial plan,” even when research suggested otherwise.

“I’ve had conversations [with colleagues] about,“Well, you know, we shouldn’t be putting that down to say it will make savings because there’s no evidence that it will,” versus me saying, “But actually we’ve still got a statutory responsibility to deliver a balanced plan, and if I take those savings out they need to come from somewhere else.” (Carla, NHS commissioning manager, Norchester) (p. 9).

Other studies revealed how evidence was mobilized strategically to secure resources. Purtle et al. [6] documented how local officials used County Health Rankings data opportunistically, sometimes to highlight need, other times to promote local assets, depending on what would attract funding. Municipal officials employed County Health Rankings data strategically, explaining they could "push on a negative" or emphasize positive aspects to secure funding or sometimes disregard the data completely [6]. “So sometimes you can push on a negative and get funding, and sometimes you can be out in the front and get funding. And of course you have a third option— they don’t even use them.” (p. 9). In practice, data were less about their empirical rigor than their utility in positioning an organization for competitive advantage in scarce resource environments.

Taken together, these findings illustrate how funding imperatives consistently mediated the role of evidence based research in municipal government politics policy and practice. Evidence was valued when it supported fiscal sustainability, leveraged external funding, or justified investments. However, when evidence conflicted with financial mandates, it was often reframed, minimized, or ignored. In this way, the political economy of resource dependence shaped the contours of evidence use as much as methodological quality or scientific consensus.

Discussion

This qualitative interpretive meta-synthesis identified three main themes that highlight the complex and frequently disputed connections between research evidence, policy development, and funding contexts. Collectively, these themes demonstrate that although evidence can shape decision-making, its impact is typically filtered through political considerations, interpersonal dynamics, and budget constraints. Our results also correspond with established theoretical frameworks for understanding evidence use in policy settings. Weiss [16] originally distinguished three types of research utilization: instrumental, conceptual, and symbolic that continue to guide current analytical approaches. Later research has expanded on these concepts. Nutley, Walter, and Davies [17], for instance, demonstrate how research evidence can guide decisions, provide justification, or face deliberate dismissal in public service environments, while Contandriopoulos et al. [18] stress the interpersonal and institutional mechanisms that determine evidence flow within policy spheres. The three patterns we identified: political filtering, dependence on trusted intermediaries, and financial pressures both reflect and build upon these theoretical foundations, revealing persistent dynamics alongside context-specific obstacles in municipal governance settings.

The first theme, Evidence Is Filtered Through Politics, Power, and Context, underscores that rarely is evidence ever received in a vacuum. Instead, evidence is tactically employed, carefully selected, or entirely dismissed according to the prevailing political and organizational context. Across these studies, research functioned in various ways: instrumentally to advance policy implementation, symbolically to validate predetermined viewpoints, or manipulatively to serve political objectives. Leadership changes, rival interests, and evolving political priorities consistently influenced whether research was used and how it was applied. This accentuates the basic inconsistency between the concept of "evidence-based policy" and the reality that evidence competes with numerous other considerations in politically driven decision-making.

Additionally, established literature and policy practice reveal that researcher credentials and institutional affiliation can considerably impact how evidence is perceived and valued. Policymakers frequently show preference for findings from recognized experts or esteemed organizations, sometimes according to these sources disproportionate influence relative to the evidence quality. Furthermore, research funding patterns typically mirror established policy agendas, resulting in greater likelihood of government funding approval for projects that complement existing priorities. These observations illustrate that evidence undergoes evaluation through multiple filters, not just political and financial factors, but also through academic reputation and the strategic incentives built into funding structures. These combined influences emphasize the intricate nature of evidence application in policy decision-making.

The second theme, Intermediaries and Trusted Brokers are Key, emphasizes the crucial function of personal and institutional relationships in either enabling or preventing research from reaching practice. Evidence achieved maximum impact when researchers, practitioners, and policymakers maintained continuous partnerships grounded in reciprocal trust. However, when interactions were disconnected or when evidence was shared without consideration for political or cultural factors, it quickly faced dismissal. This reveals that the trustworthiness of evidence frequently depends on the trustworthiness of those presenting it. Relationship that have been cultivated and are based on trust and not just research quality, typically determined whether evidence mattered in policy conversations.

The third theme, Evidence Must Compete with Funding and Resource Pressures, demonstrates how financial and administrative limitations consistently influenced how research was used in decision making. Evidence gained value when it supported budget priorities, secured outside funding, or validated spending decisions. However, when research conflicted with financial requirements or resource needs, it was reinterpreted, sidelined, or dismissed. Organizations frequently prioritized their operational survival and financial stability over implementing research driven changes. This illustrates how financial constraints, rather than the strength of research evidence, predominantly drive advocacy decisions and policy participation in human service organizations.

This synthesis has several important constraints that warrant recognition. Our analysis examined only seven qualitative studies: six conducted in U.S. settings and one in an international context. Despite being driven by homelessness policy concerns, our systematic search (January–May 2025) found no published qualitative research specifically investigating homelessness within municipal coordination frameworks. Consequently, we expanded our inclusion parameters to capture studies examining evidence use and municipal decision-making across diverse policy areas. Although this limitation restricts the precision of our findings, the recurring patterns identified: political maneuvering, trust-based relationships, and resource constraints, offer applicable insights into evidence filtering processes within municipal policy contexts. This research gap simultaneously represents an important avenue for future investigation targeting homelessness policy at both local and national levels.

Together, these results illuminate both obstacles and opportunities for social work and allied disciplines attempting to shape policy through research. Our findings indicate that evidence alone cannot drive systematic transformation. Instead, its impact relies on communication strategies, presenter credibility, and compatibility with political priorities and economic circumstances. This reinforces for social work researchers and practitioners the ongoing necessity of integrating scientific rigor with purposeful advocacy, collaborative engagement, and budget considerations. Social workers who embed evidence within the realities of political dynamics, partnership networks, and financial constraints can more effectively promote policy reforms that are both empirically grounded and practically feasible.

Collectively, these findings reveal challenges and possibilities for social work and related fields seeking to influence policy through research. The results suggests that evidence by itself cannot produce systemic change. Rather, its effectiveness depends on the methods of communication, the credibility of those presenting it, and its alignment with political goals and financial realities. For social work researchers and practitioners, this further emphasizes the continued importance of combining methodological excellence with strategic advocacy, relationship building, and financial awareness. When social workers ground evidence in the practical world of politics, partnerships, and budgets, they can better advance policy changes that are both scientifically sound and contextually relevant.

Implications for Social Work Practice and Evidence Based Research

These findings carry several important implications for social work practice, research, and policy engagement.

First, the theme Evidence Is Filtered Through Politics, Power, and Context demonstrates that social workers must recognize the intrinsic political nature of policymaking. Research evidence could lack in influencing policy without strategic framing that connects with existing priorities, addresses potential pushback, and capitalizes on opportune timing. This sheds light on the critical need for practitioners to cultivate understanding of policy dynamics and develop advocacy competencies for effective engagement in political contexts.

Second, the theme Intermediaries and Trusted Brokers are Key highlights the central role of partnerships in promoting the use of evidence. For researchers, this means moving beyond one-time dissemination efforts to cultivating sustained, reciprocal relationships with policymakers, community leaders, and advocacy groups. Situating research within reliable professional relationships ensures that findings gain visibility and influence in policy discussions. Practitioners who focus on developing alliances and earning stakeholder trust can better advocate for underserved populations and enhance the prospects for research driven policy improvements.

The final theme, Evidence Must Compete with Funding and Resource Pressures, highlights that financial and organizational constraints are unavoidable factors. Social work researchers should aim to create studies that maintain scientific rigor while considering economic factors like cost-effectiveness, long-term viability, and resource distribution. Practitioners must also learn to present evidence in financial terms that appeal to funders and policymakers. This approach helps ensure that research-based interventions are both persuasive and practical to implement.

When combined, these implications suggest that social work’s contribution to evidence-informed policy will be most effective when it integrates three commitments: (1) recognizing the political context in which evidence is applied, (2) cultivating relational trust across research, practice, and policy spheres, and (3) aligning evidence with economic and organizational realities. By knitting together these dimensions, social work professionals can help ensure that evidence not only informs policy conversations but also contributes to equitable and sustainable social change.

Limitations

Several important constraints characterize this qualitative interpretive meta-synthesis. First, despite originating from homelessness policy concerns, our literature search (January–May 2025) found no published qualitative research specifically investigating homelessness within municipal coordination frameworks. Consequently, our synthesis analyzed seven studies, six from U.S. contexts and one from the United Kingdom that examined evidence use and municipal decision-making across various policy domains. These results should be interpreted as applicable insights into evidence filtering processes within municipal policy environments, not as universally generalizable findings.

Second, the analyzed studies employed varying methodologies, research focuses, and data collection approaches. Although this diversity enriched our synthesis, contextual elements including policy sectors, study populations, and organizational frameworks likely shaped evidence interpretation and application patterns. Our identified themes may not completely reflect distinctive processes within specific policy fields.

Third, since the synthesis drew only from published peerreviewed research and one policy document, the depth of analysis was constrained by the quality and detail of original researchers' documentation. When specific perspectives received insufficient attention, especially those of community members, frontline practitioners, or marginalized groups, the synthesis could not adequately reflect the full spectrum of real world experiences. Consequently, the results primarily mirror viewpoints already established in academic and policy literature. Subsequent research could enhance this field by including unpublished materials, grassroots assessments, and practitioner narratives, thus expanding the diversity of perspectives and analytical richness.

This qualitative interpretive meta-synthesis has several limitations. First, while it incorporates seven studies, including one policy report, the body of evidence remains limited in scope. The results should be considered as exploratory insights into the ways research and evidence are screened, transmitted, and utilized within municipal and policy environments, not as complete or widely applicable findings. Second, the studies included in this QIMS differ in their methodology, objectives, and data sources. While this variation adds depth to the synthesis, there are also contextual factors to consider, participant characteristics, and the influence of policy areas on how evidence is understood and used. The cross-study themes may not fully reflect some distinctive features specific to particular settings.

Third, the synthesis relies on directly reporting what was documented in the original studies and report. The analytic depth is therefore limited by the richness and transparency of the data presented by the original authors. When certain perspectives are insufficiently captured, particularly from community members or underserved groups, the findings may not fully represent the range of experiences and viewpoints. The final limitation is that this QIMS relied predominantly on published academic research and one report, which reflected viewpoints that tend to dominate policy and research discourse. Future studies could strengthen this area by adding unpublished documents, community-conducted evaluations, and practitioner perspectives to represent a more comprehensive range of voices and experiences. Consistent with qualitative research principles, this synthesis follows transferability instead of generalizability. Therefore delivering insights that could be applicable in different situations while preserving ties to the original study contexts.

Conclusion

This qualitative interpretive meta-synthesis demonstrates how political dynamics, communication approaches, and economic constraints influence the application of research evidence in municipal and policy settings. Analysis of seven studies revealed three key themes. First, evidence undergoes political filtering through power structures and contextual factors. This shows that research findings seldom stand alone, but are negotiated, modified, or opposed based on conflicting interests. Second, effective evidence translation requires credible intermediaries who can present findings in accessible ways that connect with policymakers, stakeholders, and community members. Research that is locally relevant, well-timed, and linked to real experiences has greater potential for impact and lasting policy change. Third, evidence must continually compete against funding and resource demands, by demonstrating that budget considerations frequently take precedence over research findings in policy development.

Collectively, these themes reveal that while research can guide and support policy development, it cannot single-handedly drive change. The effectiveness of research findings depends on how well it aligns with political priorities, institutional objectives, and budgetary realities. For social work researchers and practitioners, this highlights the importance of moving past simply generating evidence. Effective engagement requires converting research into understandable formats, building relationships with influential decision-makers, and recognizing the institutional and financial obstacles that affect policy implementation. To this end, the QIMS supports the opportunities and challenges inherent in evidence-informed policymaking. Social work scholars and practitioners who contextualize research within broader social, political, and economic frameworks can better harness evidence to promote just, flexible, and lasting policy improvements.

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Friese, B., & Bogenschneider, K. (2009). The voice of experience: How social scientists communicate family research to policymakers. Family Relations, 58(1), 92–107. View

Wye, L., Brangan, E., Cameron, A., Gabbay, J., Klein, J. H., & Pope, C. (2015). Evidence-based policy making and the ‘art’ of commissioning—How English healthcare commissioners access and use information and academic research in ‘real life’ decision-making: An empirical qualitative study. BMC Health Services Research, 15, 430. View

Allen, K., Bean, C. J., & Farnsworth, S. K. (2015). Policymakers’ use of academic research. The Journal of Higher Education, 86(2), 277–304.

Nelson, S. R., Leffler, J. C., & Hansen, B. A. (2009). Toward a research agenda for understanding and improving the use of research evidence. Educational Researcher, 38(1), 3–14. View

Jabbar, H., Li, D., & Wilson, T. (2014). The politics of performance: How political factors shape the use of research evidence in education. Educational Policy, 28(2), 243–270.

Purtle, J., Lê-Scherban, F., Wang, X., Shattuck, P. T., Proctor, E. K., & Brownson, R. C. (2019). Use of data to inform local health policy: Results from qualitative interviews with county officials. Preventing Chronic Disease, 16, E80.

Aguirre, R. T., & Bolton, K. M. (2013). Why do they do it? A qualitative interpretive meta-synthesis of crisis volunteers' motivations. Social Work Research, 37(4), 327-338. View

Burse, J., McElwee, T. M., Heldman, E., Campbell, H. B. (2024). Unveiling the Silent Struggle: Exploring Intimate Partner Violence among Older African American Women: A Qualitative Interpretive Meta-Synthesis (QIMS). Journal of Clinical Nursing Reports 3 (2), 01, 9. View

Barnett, T. M., McFarland, A., Miller, J. W., Lowe, V., & Hatcher, S. S. (2019). Physical and mental health experiences among African American college students. Social Work in Public Health, 34(2), 145-157. View

Watkins, J., Barnett, T. M., Collier-Tenison, S., & Blakey, J. (2019). Why don’t they listen to me: A Qualitative Interpretive Meta Synthesis of a child’s perception of their sexual abuse. Child and Adolescent Social Work, 36(1), 337-349. View

Patterson, Y. K., & Barnett, T. M. (2017). Experiences and Responses to Microaggressions on Historically White Campuses: A Qualitative Interpretive Meta-Synthesis. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 44(1), 3-26. View

Barnett, T. M, Bowers, P. H., & Bowers, A. (2016). Using a social justice lens to examine and understand the experiences of sexual minority women who struggle with obesity: Qualitative interpretive meta-synthesis (QIMS). International Journal of Public Health, 8(2), 121-136.

Barnett, T. M., & Praetorius, R. T. (2015). Knowledge is (not) power: Healthy eating and physical activity for African- American women. Social work in health care, 54(4), 365-382. View

Barnett, T.M., & Aguirre, R.T.P. (2013). A Qualitative Interpretive Meta-synthesis (QIMS) of African Americans and Obesity: Cultural acceptance and public opinion. Hawaii Journal of Medicine and Public Health, 72(8 Suppl 3): 23. View

Mosley, J. E. (2012). Keeping the lights on: How government funding concerns drive the advocacy agendas of nonprofit homeless service providers. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 22(4), 841–866. View

Weiss, C. H. (1979). The many meanings of research utilization. Public Administration Review, 39(5), 426–431. View

Nutley, S. M., Walter, I., & Davies, H. T. O. (2007). Using evidence: How research can inform public services. Policy Press. View

Contandriopoulos, D., Lemire, M., Denis, J. L., & Tremblay, É. (2010). Knowledge exchange processes in organizations and policy arenas: A narrative systematic review of the literature. The Milbank Quarterly, 88(4), 444–483. View