Journal of Social Work and Welfare Policy Volume 3 (2025), Article ID: JSWWP-169

https://doi.org/10.33790/jswwp1100169Research Article

Indigenous University Student Wellness in Canada: A Review of Challenges, Strengths, and Gaps

Walter Wai Tak Chan1*, Jihad (Rosty) Othman2, Carla Loewen3, Teryn Bruni4, Dhaval Patel4, Brian Lester5, and Mayesha Verma4

1School of Social Work, Algoma University, Bawating, 1520 Queen St E, Sault Ste. Marie, ON P6A 2G4, Canada.

2Department of Sociology & Criminology, University of Manitoba, Canada.

3Mathias Colomb Cree Nation, Indigenous Student Centre, University of Manitoba, Canada.

4School of Psychology, Algoma University, Canada.

5Algoma University Students’ Union, Canada.

Corresponding Author Details: Walter Wai Tak Chan, Algoma University, Bawating, 1520 Queen St E, Sault Ste. Marie, ON P6A 2G4, Canada.

Received date: 04th September, 2025

Accepted date: 19th November, 2025

Published date: 25th November, 2025

Citation: Chan, W. W. T., Othman, J. R., Loewen, C., Bruni, T., Patel, D., Lester, B., & Verma, M., (2025). Indigenous University Student Wellness in Canada: A Review of Challenges, Strengths, and Gaps. J Soci Work Welf Policy, 3(2): 169.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Numerous studies have previously documented the challenges Indigenous students face in Canadian universities, including finances, lack of institutional support, distance from family, childcare responsibilities, and persistently high levels of anti-Indigenous racism. In this topic review, we searched Sociological Abstracts, PsycINFO, and ERIC from January 2020 to August 2025 for articles, books, and theses pertaining to these search terms: Indigenous, Canada, student, university, wellness, success. We narrowed the sample to sixteen (16) papers. We describe wellness from an Indigenous perspective (mainly drawn from Secwepemc, Anishinaabe, and Cree/Nehiyaw traditions). The key factors enhancing Indigenous student wellbeing include funding supports and culturally affirming academic supports. It is not known how issues of Indigenous intersectionality influence student wellbeing. There is also a literature gap regarding the specific experiences and challenges of studying in disciplines where there seem to be very few Indigenous students and faculty – engineering, physical and biological sciences, mathematics (STEM), and medicine. We close with recommendations for validated approaches to supporting Indigenous students, aligned with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada calls to action. These include honoring the promises made for First Nations student funding and for strengthened Indigenous governance and decision-making in academia.

Keywords: Indigenous, Canada, Student, University, Wellness, Success,Anti-Indigenous Racism, STEM

Introduction

Indigenous students have been enrolling in Canadian universities in growing numbers since the 1960s. There are increasing numbers of Indigenous university graduates; however, their rates of university completion lag behind those of non-Indigenous students, with 12.9 percent of Indigenous people holding a Bachelor’s level degree or higher compared to 33.8 percent of Canadians [1,2]. There have been persistent calls from Indigenous students who assert that Canadian universities are unfriendly, racist, and demoralizing environments. These calls have been largely substantiated in the research literature [3-5]. The colonial and structural mechanisms that exist within Canadian universities contribute to Indigenous suffering and have a significant impact on Indigenous student success. Reviewing the recent literature, this topic review article examines the challenges Indigenous students face at university, the gaps in our knowledge about the Indigenous student experience, and how Indigenous student wellness can be enhanced in alignment with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s calls to action.

Generally speaking, four processes of cultural disadvantage can be identified as negative forces impacting Indigenous university students. Although this was an American study, the results provide some insights about Canadian Indigenous student experiences. These include stereotyping, the de-legitimation of Indigenous histories and knowledge systems, assimilation pressures, and a cultural permissibility of ignorance [6]. Although these processes are likely just as prevalent, if not more so, in the broader society outside of universities [7], they highlight the challenges Indigenous students face. Indigenous students often experience cognitive dissonance related to studying within institutions, touted as exemplars of enlightened thought, while regularly dealing with instances of microaggressions on campus, curricula which do not reflect or respect Indigenous knowledge systems, and pressure to conform to White culture and deny one’s own Indigeneity. Persistent threats of racism wear down Indigenous individuals’ health and wellbeing, which can be physiologically measured through the concept of allostatic (stress response) load [7,8].

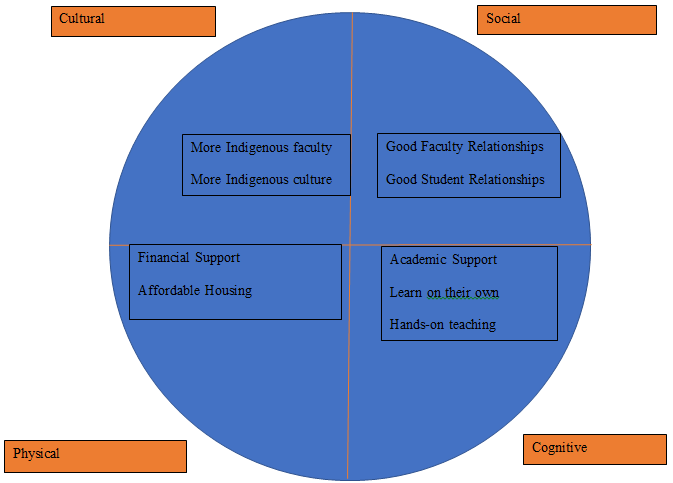

From previous research and from longstanding Indigenous ways of life (citing Elder Mike Arnouse, Secwepemc), wellness and success for Indigenous students can be said to consist of four components in a circle [9] (refer to Figure 1): social, cognitive, physical, and cultural. The social component consists of good relationships with faculty and students. The cognitive component consists of academic support, hands-on learning, and learning on one’s own. The physical component comprises financial support and affordable housing, especially important for students who are single parents. And the cultural component includes having more Indigenous cultural events and more Indigenous faculty at university. We can see from the data and recommendations noted below from our pool of studies that these four circle components contribute to Indigenous student success in higher education.

Methods

We searched Sociological Abstracts, PsycINFO, and ERIC from January 2020 to August 2025 for articles, books, and theses related to the following search terms: Indigenous, Canada, student, university, wellness, success. We included only the studies about Canadian universities. We excluded studies that were not peer-reviewed, such as newspaper or magazine articles, organizational grey literature, and editorial commentaries. We excluded studies which did not focus on the student experience, such as analyses of admissions procedures. Thus, in this review we included peer-reviewed articles, graduate theses, and books, including papers which were conceptual in nature but not empirical studies. The search on Sociological Abstracts procured over 2000 results, while the PsycINFO search procured 11 results. (We searched ERIC using the same terms but only received one result.) Sifting through the results according to our criteria, we narrowed the sample to sixteen (16) papers (refer to Table 1).

Throughout the search and writing process, we employed as sensitizing ideas Indigenous soul and soul healing (Duran, 2019), Indigenous historical trauma [10], as well as the wellness and success circle [9].

A limitation of this paper was our focus on psychological, sociological, and educational literature. We did not search literature for the smaller healthcare professions (e.g., kinesiology, speech therapy, veterinary science) or for performing arts and fine arts disciplines.

Results

Included studies indicated financial struggles, a lack of institutional support, and distance from families as significant hardships facing Canadian Indigenous students. Compared to non-Indigenous students, who may enter university directly from high school and be more economically advantaged, Indigenous students were often older, had less savings, and were more likely to have children [11]. These circumstances put many Indigenous student under financial strain, compounded by other family responsibilities such as parenting which also significantly increases financial pressure. Federal and band (First Nations) funding for Indigenous students has shrunk, and these streams also came with complicated bureaucratic application procedures [9,11]. Most Indigenous students did not receive sufficient funding to cover their day-to-day expenses. Financial hardship was a major factor contributing to the fact nearly half of Walton et al.’s [9] sample of Indigenous students in Western Canada dropped out of university.

Generally, studies suggested Canadian universities were providing modest, but often inadequate, support to Indigenous students1. Indigenous knowledge systems as such were usually confined to a very narrow band of courses. Indigenous ways of learning and attention to the specific needs of Indigenous students seemed to be rarely respected or understood by university staff and curriculum. Cech, Smith, & Metz [6] called this lack of knowledge cultural permissibility of ignorance in settler contexts. Campus initiatives for cultural safety and anti-racism work were unevenly applied across departments. Many departments paid only lip service to these initiatives. There was an almost unanimous call for increasing the currently very small number of Indigenous professors in Canadian universities. And for Indigenous mothers and parents who are also students, universities were often completely lacking in institutional support. This gap was especially acute for single parents (e.g., for childcare, accommodations for due dates, course times, lectures and events in which it is possible to bring one’s child) [3, 11]2.

Discussion

Moving away from family is daunting. For students from reserves, the transition to university and urban life can be highly difficult [3,7,11]. Indigenous students often need to rebuild their social networks and support systems. They may fear losing their connection to their home communities and culture, which may be seen as non-replenishable. That is, home communities’ social fabric and Indigenous knowledge systems are perceived to be under threat by ongoing forces of settler colonialism in Canada. These perceptions, underwritten by Canada’s structural oppression, may increase their sense of isolation and alienation. Bailey’s 2020 study noted low levels of interaction between Indigenous and non-Indigenous students. Extreme isolation as perceived by Indigenous students and the perceived ignorance of non-Indigenous students and staffs were seen as key contributors to a structure of racism toward Indigenous peoples [3] in university.

Then, there are the cultural and personal challenges Indigenous students face. Many were the first in their families to attend university and may therefore experience lower levels of support and socialization from their family in preparation for higher learning compared to non-Indigenous students, although not all studies corroborated this [11,14]. Indigenous students were more likely to be parents than other university students. In Cameron et al.’s sample, nearly half were parents. In particular, female Indigenous students who are parents often feel overloaded by the multiple roles they must fulfill. They “struggle with balancing their obligations to school and to their family. Indigenous parents attending university [were] also more likely to have difficulties finding housing, which can contribute to difficulties balancing domestic obligations and studying” [11].

Most studies indicated Indigenous students face persistently high levels of anti-Indigenous racism [3,7]. There seemed a consistency of the quantity and severity of racist incidents the students faced across different institutional settings [4,5]. Examples of overt racism included: posters and media espousing White supremacy, hearing malicious stereotypes, and overt dismissals of Indigenous history and nationhood. Overt and systemic racism led to low self efficacy among Indigenous students. Students did not feel good enough to be at university which could lead to them to hide their Indigenous identity [4]. Students reported feeling stereotyped (e.g., considered to be a freeloader) and often felt obligated to educate others in response to their Indigenous history being challenged or dismissed [3]. Students often felt obligated to provide pedagogical and emotional labor to settlers regarding Indigenous rights and anti Indigenous racism. Simultaneously, they felt on-guard to fight back or speak out when confronted with racist behavior and policies [3,15]. These perceived obligations to do the right thing on the behalf of others came at a sometimes high emotional and physiological cost for Indigenous students [8].

Areas in Need of Further Study

It is interesting that few studies, with the exception of Bailey [3], dealt with Indigenous intersectionality. In Canada, there are – as it is with most ethnic groups – many social identities under the umbrella of the term Indigenous, involving intersections of class, ethnicity (e.g., White Canadian identity in tandem with Indigeneity, belonging to more than one Indigenous nation), gender, sexuality, and disability, to name a few. Study findings which lump together all Indigenous people into one category obscure the nuances of social experience which align complexly with intersecting identities. There was a lack of data on Two-Spirit university student experiences. For instance, Walton et al.’s [9] sample consisted of only one Two-Spirit student.

Bailey’s [3] work suggested Indigenous female students are taking greater leadership than male students in university settings. However, Indigenous women overall still perform more onerous and frequent emotional labor than their male counterparts to both fight for their rights and to fit into hegemonic settler expectations. Although male students in Bailey’s study found themselves to be isolated, they acknowledged their relatively greater ease in feeling safe on campus and being less burdened by childcare or other family responsibilities. It was suggested Indigenous mothers of very young children who are university students experience some of the most severe burdens and isolation [9].

From the studies garnered, only six studies focused on STEM students, including one for rehabilitation sciences [4], medicine [16], nursing [17], and dietetics [18]. Robinson and Shankar [19] showed very small numbers of self-reported Indigenous students in STEM, reportedly being less than 1 percent of those enrolled in introductory STEM courses like chemistry at a large medical doctoral Quebec university [20]. In the health sciences programs, the proportion of Indigenous students seemed to be higher but still small [18]. STEM programs including the health sciences were described as being especially competitive and high pressure. It was suggested STEM programs tended to assume and foster somewhat isolated individualism and self-reliance, which may be incongruent to Indigenous students’worldviews (Robinson & Shankar). Alarmingly, in health sciences, it was described that Indigenous students often faced a hostile academic climate marked by subtle disparagement of Indigenous knowledge systems, institutional racism, and a curriculum which was evasive regarding issues of racism and colonization [16]. In nursing, Van Bewer [17] noted frankly oppressive and hostile academic settings being all too common – verbal abuse, humiliation, microaggression, and anti-Indigenous racism. In rehabilitation sciences and medicine, there seemed to be a common assumption that Indigenous students were inferior. Due to equity-based enrollment, they were perceived as unfairly taking a seat away from more qualified students. What was striking was that some Indigenous students felt they needed to hide their Indigeneity to acquire and assimilate into a healthcare professional identity [4].

In the physical sciences (e.g., physics, chemistry) and mathematics, the experiences of Indigenous students are unknown, as we did not garner sufficient information from our search [20]. Future research should focus on Indigenous student perspectives in physical science and mathematics. Also due to the lack of information, we highly recommend future studies take an intersectional lens – the intersections of class, “race,” gender, disability, sexuality, and gender identity – to examine Indigenous university student experiences. And there is a need for future studies to document and validate Two-Spirit university student experiences.

Strengths of Indigenous Students

Despite the challenges and barriers Indigenous university students face, it is important for us to highlight and recognize their successes, strengths and accomplishments. What we saw in the studies demonstrated Indigenous student self-reliance and a strong desire to succeed, for personal satisfaction, career goals, and the betterment of their communities.

From the studies reviewed, it was clear Indigenous students continued to face a lack of institutional support, financial struggles (especially for female single parents), pervasive and high levels of on-campus anti-Indigenous racism, and perceived distance from home and family. It also was the case increasing numbers of Indigenous students were entering and graduating from university than ever before, a hopeful sign. The studies indicated the social, cognitive, physical, and cultural supports appropriate for Indigenous students, especially financial and childcare supports, needed to be in place for this upward trend to continue.

In terms of strengths, we saw in the studies that Indigenous students put a premium on self-reliance. In part, it seemed to satisfy the dominant, quite individualistic Canadian academic worldview of studying hard, individual achievement, and intellectual brilliance, most strongly expressed in STEM and perhaps the healthcare professions [19]. From an Indigenous perspective, some students were raised to be self-reliant and not interfere with others, within a respectful individualistic and holistic worldview. This can lead to being somewhat reserved and cautious about seeking help. However, it seemed both orientations may lead to a somewhat isolated existence in university, as students in reality cannot be individually brilliant, education being a highly social endeavor, and often must seek help to improve their skills even when self-reliance and confidence are marred by the many barriers that already exist for them in university. Reading between the lines, we can see that some Indigenous students adeptly became self-reliant and trusted their own decisions to seek help when it seemed feels safe and appropriate to do so. Indigenous students actively seek academic supports like tutoring and study groups, community-building opportunities, and campus social activities for a sense of belonging. Importantly, they sought and wanted opportunities for cultural learning, ceremony, and traditional and spiritual knowledge. We also saw the strength of Indigenous women-led student groups and Indigenous centers, as more Indigenous women than men attend university, with strong teachings and caring communities being established. However, even within these Indigenous student groups, some Indigenous students felt a lack of belonging due to questions of intersectionality and tribal/national affiliations (e.g., being Inuk in a non-Inuit Indigenous student group) [3].

Conclusion

To conclude, two key areas stand out as barriers for Indigenous university students and we link them to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) Calls to Action. First, students are burdened by financial struggles, in the context that since the Indian Act, Canada has consistently blocked the ability of Indigenous communities to carry out commerce and build an economic base (e.g., by such coercive impositions as the reserve system) on their own terms. These economic disadvantages are rooted in colonial policies that have aimed to benefit dominant society while simultaneously taking away resources and land that could have otherwise benefited Indigenous communities. As these injustices become increasingly taken to task by Indigenous communities, advocates and leaders, it is clear that one way forward is to increase the funding available to First Nations students as a start. It seems high time for Canada to heed the TRC Call to Action No. 11 (2015), “We call upon the federal government to provide adequate funding to end the backlog of First Nations students seeking a post-secondary education” as a partial compensation. With a cap of 25,000 First Nations students funded per year by the federal Post-Secondary Student Support Program set in 1996 [21] and subsequent increases in the Indigenous population, it is evident that support for Indigenous educational attainment is still not being taken seriously by the government.

Second, institutional support for Indigenous students has been lacking, and universities themselves continue to demonstrate rather consistently high levels of anti-Indigenous racism. It suggests a holistic transformation of the university structure is required, at the level of governance, from being settler-focused and Eurocentric to treaty rights-centered. We highlight Sedgwick, Crosschild, Rohatinsky, & Scott [22]’s recommendation, for Indigenous boards of governors to comprise of traditional Indigenous elders/knowledge holders, “local Indigenous scholars and educators, and Indigenous students whose mandate is to develop, implement, and oversee policies and practices that directly affect Indigenous students and allow them to become part of universities’ governance models.” A holistic transformation would help to accelerate the filling in of the gaps in historical and current knowledge in Western institutions that perpetuate ignorance about Indigenous peoples in the public sector and beyond [8], which is a barrier facing many learners. We believe this measure would move universities closer towards the community responsibility, control, and accountability the TRC called for [23]. It would also help to decrease the chances that universities will repeat the same mistakes repeatedly, as reconciliation shall mean not having to say sorry twice [24].

We acknowledge these conclusions do not fully reflect the complex nature of being an Indigenous student in a post-secondary setting and honor the resilience, self-reliance, and tenacity it takes to navigate the hallways of Western institutional constructs. Another limitation of this paper is that the studies reviewed had an emphasis on the First Nations student experience. The Métis and Inuit student experience are equally complex with distinct historical considerations that warrant further study as well.

Competing Interests:

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

Melvin, A. (2023). Postsecondary educational attainment and labor market outcomes among Indigenous peoples in Canada, findings from the 2021 Census. Statistics Canada. View

Statistics Canada. (2018, March 27). Canada at a glance 2018: Education. View

Bailey, K. A. (2020). Racism within the Canadian university: Indigenous students’ experiences. [Doctoral dissertation, McMaster University]. MacSphere. View

Brown, C., Ducharme, D., Hart, K., Marsch, N., Chartrand, L., Campbell, M., Peebles, D., Restall, G., Fricke, M., Murdock, D., & Ripat, J. (2024). Diversity and development of Indigenous rehabilitation professional student identity. BMC Medical Education, 24, 595. View

Efimoff, I. H., & Starzyk, K. B. (2025). A mixed methods investigation of Indigenous university students’ experiences with and strategies to challenge racism. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. View

Cech, E., Smith, J., & Metz, A. (2019). Cultural forces of ethno racial disadvantage among Native American college students. Social Forces, 98 (1), 355–380 View

Currie, C. L., Motz, T., & Copeland, J. L. (2020). The impact of racially motivated housing discrimination on allostatic load among Indigenous university students. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 97(3), 365–376. View

Currie, C., Copeland, J., Metz, G. A., Chief Moon-Riley, K., & Davies, C. (2020). Past-year racial discrimination and allostatic load among Indigenous adults in Canada: The role of cultural continuity. Psychosomatic Medicine 82(1):p 99-107, January 2020. View

Walton, P., Hamilton, K., Clark, N., Pidgeon, M., & Arnouse, M. (2020). Indigenous university student persistence. Canadian Journal of Education/Revue canadienne de l'éducation, 43(2), 430–464.View

Gone, J. P., Hartmann, W. E., Pomerville, A., Wendt, D. C., Klem, S. H., & Burrage, R. L. (2019). The impact of historical trauma on health outcomes for indigenous populations in the USA and Canada: A systematic review. The American Psychologist, 74(1), 20–35. View

Cameron (Anishinaabekwe), R. E., Bird, M. J., Naveau Heyde (Mattagami First Nation), D. D., & Fuller-Thomson, E. (2024). Creating a “sense of belonging” for Indigenous students: Identifying supports to improve access and success in post-secondary education. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 20(4), 732-740. View

MacNeil, E., Marquardt, D., & McLennan, H. (2021). Combining Western evidence-based psychological counselling practice and theory with Indigenous cultural wellness practices. Research and Evaluation in Child, Youth, and Family Services, 3, 40-56. View

Hartmann, W. E., & Gone, J. P. (2012). Incorporating traditional healing into an urban American Indian health organization: A case study of community member perspectives. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 59(4), 542–554. View

Layton, J. (2023). First Nations youth: Experiences and outcomes in secondary and postsecondary learning. Statistics Canada. View

Park, A. S., & Bahia, J. (2022). Exploring the experiences of black, Indigenous and racialized graduate students: The classroom as a space of alterity, hostility, and pedagogical labor. Canadian Review of Sociology, 59(2), 138–55. View

DHont, T., Stobart, K., & Chatwood, S. (2022). Breaking trail in the Northwest Territories: a qualitative study of Indigenous Peoples’ experiences on the pathway to becoming a physician. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 81(1), 2094532. View

Van Bewer V. (2023). Trauma and survivance: The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on Indigenous nursing students. Nursing Inquiry, 30(1), e12514. View

Stein, S., Robin, T., Wesley, M., Valley, W., Clegg, D., Ahenakew, C., & Cohen, T. (2023). Confronting colonialism in Canadian dietetics curricula. Canadian Journal of Dietetic Practice and Research, 84(4), 226-232. View

Robinson, K. A., & Shankar, S. (2025). Motivational trajectories and experiences of minoritized students in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics: A critical quantitative examination of existing data. Journal of Educational Psychology, 117(3), 337–360. View

Kumblathan, T., Borg, G. C., Morrissette, C., Clark, W. I., Le, X. C., & Li, X. F. (2025). Advancing equity and empowering science students from Indigenous communities. Analytical Chemistry, 97(2), 1041–1046. View

Assembly of First Nations. (2018). First Nations post secondary education fact sheet. View

Sedgwick, M., Crosschild, C., Rohatinsky, N., & Scott, D. R. (2025). Resilience among indigenous graduate nursing students: A scoping review. Quality Advancement in Nursing Education - Avancées En Formation Infirmière, 11(1), 1-24,1A. View

Persaud, J. N., Wannamaker, K., Stark, K., Lambert, C., Harrison, C., & Keller, N. (2025). Decolonizing education: Advancing Indigenous student success through culturally responsive practices in Ontario. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 21(2), 264-273. View

Blackstock, C. (2018). Reflections on reconciliation after 150 years since Confederation–An interview with Dr. Cindy Blackstock. Ottawa Law Review. View