Journal of Social Work and Welfare Policy Volume 3 (2025), Article ID: JSWWP-170

https://doi.org/10.33790/jswwp1100170Research Article

BSW Students’ Commitment to Social Activism: A Model

Michele Brown1*, Amanda M. Keys2, Jessica Willis3, Amber Yanez4, and Tiffany Havlin5

1Associate Professor, School of Mental Health and Behavioral Sciences, Missouri State University, 901 S. National Ave. Springfield, MO 65897, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Michele Brown, Ph. D., MSW, LMSW, Associate Professor, School of Mental Health and Behavioral Sciences, Missouri State University, 901 S. National Ave. Springfield, MO 65897, United States.

Received date: 18th September, 2025

Accepted date: 24th November, 2025

Published date: 26th November, 2025

Citation: Brown, M., Keys, A. M., Willis, J., Yanez, A., & Havlin, T., (2025). BSW Students’ Commitment to Social Activism: A Model. J Soci Work Welf Policy, 3(2): 170.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

CSWE [1] and NASW [2] provide social work educators with the language needed to address social change. However, they do not explain what motivates students to want to engage in change. Until educators begin to understand the “why” behind what motivates students to engage in social activism, educators will continue to be unequipped to move students from social activism vocabulary to social activism behaviors. A model is discussed that describes BSW students’ commitment to social activism. The model hypothesized how personality and social structure predict civic attitudes, moral identity, and opportunity which predicts social activism. Two hundred and twenty-four BSW students were surveyed for this study. Structural equation modeling was performed to assess the social activism model. The results suggest that the hypothetical model provides a moderate fit to the data χ2(287) = 444.56. More research needs to be completed to further explore these findings and the influences on social activism.

Keywords: Advocacy, Social Justice, Social Work Curriculum, Personality Characteristics, Civic Engagement, Participation

Introduction

Racial inequality, climate change, affordable healthcare, voting rights, food insecurity, gun violence, and disability rights are just a few of the many social justice issues affecting the United States. While the nation grapples with how to solve these problems, the social work profession has yet to define social justice or measure social workers’ involvement in activism activities [2,3]. Bent-Goodley [5] recently articulated this by asking social workers if social activism was still happening. Compounding these issues further are variations in how social activism is taught in social work education [6-8]. These inconsistencies have left the profession vulnerable to negative critique and without clarity on how to resolve these concerns.

The juxtaposition of current social activism trends and historical social activism movements led by social workers must not be minimized. Historically, social activism has played a tremendous role in establishing the social work profession [9]. The past century provides many examples of how social work pioneers have led revolutionary social movements. Currently, as activism by and for underrepresented populations unfolds, social workers remain mostly silent [10]. Is it realistic to expect social workers to engage in social activism [11]? The authors of this article feel that it is not only realistic, but necessary, to continue to propel our profession in becoming vociferous global advocates for underrepresented communities.

The NASW Code of Ethics [2] supports this effort. They state social work researchers have an ethical responsibility to study this phenomenon [2]. This paper does this by starting at the beginning- with BSW students. It presents a model that describes BSW students’ commitment to social activism. The purpose for exploring this model is to better understand the psycho-social influences on BSW students’ commitment to social activism. This model should serve to inform future research and social activism curriculum.

Review of Relevant Scholarship

Social activism has been described as the lived commitment to social justice [12]. Social justice is the value that distinguishes social work from other helping professions. The value requires social workers to “challenge social injustice” and “pursue social change, particularly with and on behalf of vulnerable and oppressed individuals and groups of people” [2]. The Council on Social Work Education [CSWE] [1] supports this professional dictate by requiring social work programs to teach students how to globally advance social, economic, and environmental justice. Baccalaureate programs have responded to these standards by incorporating social justice content throughout their curricula [13]. Some departments even have specialized courses in social justice [14].

CSWE presumes that when social work students obtain a BSW degree, they will know how to define social justice and actively integrate social activism into their practice [1]. However, is this belief founded in reality? Few evidence-based curricular models exist to teach students how to engage in social justice, and assessments of student knowledge vary across BSW programs [15-17]. The lack of evidence-based curriculum has made it challenging for BSW programs to effectively meet CSWE’s mandate.

There is also uncertainty about what is the best way to incorporate activism into BSW curriculum. Benner and colleagues [6] found there was no statistical difference in student learning in a course infused with social justice content versus a course that solely focused on social justice. This may be due to social work faculty and their inability to effectively integrate social justice issues into their course content [18]. Researchers suggest it takes more than just successfully incorporating social justice content into the curriculum. For students to actively engage in social activism, faculty must go beyond the classroom and involve their students in their own social activism efforts [19]. This can be challenging when activities that are shown to decrease student activism levels are racial privilege [20] and instructors’ inability to share and connect their passion to activism [21]. However, a recent study by Jacob and Bentley [22] with BSW students provides promise towards a model that bridges a gap between practice and research and promotes social change. While this study had promising results for participants recognizing how the research directly impacts advocacy work, additional research is warranted to determine this model’s efficacy.

Previous literature on social work students and their beliefs on social activism has also shown inconsistent findings. Researchers have found students who are exposed to social justice curriculum are more likely to engage in activism [23,24]. Specific areas of activism include political participation and multicultural activism [25]. Research has simultaneously found that social work students have very little interest in engaging in practices to combat social justice [26,27]. These contradictions further perplex researchers trying to understand BSW students’ motivations to engage in social activism by suggesting that not all BSW students desire to participate in social activism.

These inconsistencies might be due to differences in BSW students’ social justice beliefs versus their desired involvement in social activism endeavors. Although a BSW student might believe in eradicating injustice, that student might not be motivated to engage in social activism activities to eradicate them. Knight’s [19] research on BSW and MSW students’ perceptions of the Freddie Gray Case supports this. Participants lived in Baltimore and had experienced firsthand the events that unfolded after Gray’s death. Findings indicated that while students stated that they were committed to social justice and distressed by Gray’s death, their beliefs were not translated into social activism. Golden’s [28] research with BSW students had similar findings; even though students have positive perceptions of social justice and advocacy, this does not necessarily translate to social activism.

Access to engage in social activism activities might also be an important consideration in this discussion. Recent social work graduates reported limited opportunities to apply social activism into their practice experiences [29]. Is this because there are no activism activities available or is it because BSW programs and field agencies are not emphasizing the importance of these activities? Research suggests it might be the latter. Social work programs spend more time teaching micro skills [30]. This is primarily because BSW programs recognize that post-graduation, most social workers are employed in micro settings in the United States [31]. Consequently, BSW programs have adjusted their curriculum to meet this need. Research has found micro social workers are less likely to engage in social activism than their macro counterparts [32]. As a result, BSW programs focusing more on micro education and less on macro education will continue to perpetuate the lack of social activism opportunities for social work students.

Irrespective of why there are inconsistencies in teaching and student activism levels, social work programs have the ethical responsibility to promote student activism [1,2]. There has been a considerable research gap in understanding specific student characteristics that increase the likelihood of engagement in activism activities [25]. More recent studies are beneficial in better understanding student characteristics and activism involvement [33, 34]. Reeser and Epstein [35], in their seminal research comparing social activism levels of NASW members in the 60’s and 80’s, began this process by collecting data on social workers’ characteristics. Their focus included gender, race, religion, age, and political beliefs. They found activism level differences based upon all characteristics measured.

The relationship between political beliefs and social activism levels is one student characteristic that has continued to be studied. Dodd and Mizrahi [4] assert that students who identify as sexual minorities, hold radical political beliefs, and who self-select into community organizing practices participate more in activism activities. These findings supported prior research by Dodd and Mizrahi [4] that found students who identified as politically “radical” had higher levels of social activism. This is interesting when comparing these findings to a recent study that discovered many social work students sampled did not perceive political activism as an important social justice action [36].

To develop a model focusing on BSW students’ characteristics that encourage activism, two important things were considered. The first characteristic was the theory that underpinned model development. The authors based their research on Bandura’s [37] social cognitive theory. Social cognitive theory postulates that individuals have autonomy and freedom over their actions and are not just passive participants [38]. The theory suggests that change takes place when people believe that they can make a difference. When specifically focusing on social work students, this theory suggests that students must have the confidence that they can make societal change to engage in social activism activities. This theory fits well when focusing on social activism and has underpinned previous research studying students’ commitment levels to social activism [39,40].

Second, the social activism model developed was based upon a model previously done that focused on an individual’s commitment to volunteering [41]. Previous research supports that volunteering and social activism are similar constructs that often overlap [42,43]. Bales [44] treated volunteerism and social activism synonymously, as volunteering for charitable organizations often promotes community awareness and social change. Janoski [45] broke this down further by describing social activism as volunteering that focuses on societal change.

The volunteering model the social activism model was based on was developed to explain the psychological and social-structural characteristics that influenced an individual’s commitment to volunteering [41]. The volunteering model focused on how an individual’s personality, social structures, moral cognition, civic attitudes, and opportunities influenced volunteering. This model was grounded in social cognitive theory and adapted from Matsuba et al.’s [41] volunteering model. The variables used in this model were replicated when developing the social activism model. Different items, however, were used to measure each variable for several reasons. These were to reduce the survey length and to add an additional validated instrument to measure the construct of moral cognition. Also, the original model specifically discussed volunteering and sampled households over the age of twenty-five. Since the focus of this model was social activism, and most of our participants were under age twenty-five, we felt it was appropriate to modify the questions.

This study differs from previous studies because it begins to explore the psycho-social influences on BSW students’ commitment to social activism. The purpose of this study is to spur continued conversation on how to understand, support, and encourage students’ desires to engage in social activism. Inconsistencies across BSW curricula and a lack of evidence-based social activism models have left social work educators feeling ill-prepared to understand and, therefore, equip students with advocacy behaviors and skills. CSWE [1] and NASW [2] provide social work educators with the language needed to address social change. However, they do not explain what motivates students to want to engage in change. Until educators begin to understand the “why” behind what motivates students to engage in social activism, educators will continue to be unequipped to move students from social activism vocabulary to social activism behaviors.

Method

Participants

A model was developed to describe BSW students’ commitment to social activism hypothesizing personality and social structure would predict students’ civic attitudes, moral identity, and opportunity. This research used a cross-sectional survey research design that employed non-probability purposive sampling. The university’s Institutional Review Board approved this study. Recruitment took place at a large Midwestern public university. All undergraduate students with declared majors in social work were recruited to participate. Participation was sought through undergraduate social work courses. Instructors consented to asking students to participate in a Qualtrics survey. Instructors provided time for students to go to a computer lab during their class to participate. Research assistants prepared each computer in the computer lab, prior to students entering, to have the survey ready. Informed consent was obtained by all participants prior to participating in the study. Students were assured that participation in the study was voluntary and there were no penalties or rewards for their participation. Two hundred and twenty-four BSW students completed the Qualtrics survey.

Measures

Social Structure

Most participants were seniors (38.9%) followed closely by junior social work majors (32.29%). Eighty-five percent of participants described themselves as living in a rural or suburban area. The majority were female (87.5%), heterosexual (83.5%), and Caucasian (83%) that came from homes with diverse familial educational backgrounds. Most participants had parents who had some education post-high school (65.4%). These demographic characteristics are consistent with previous research done on social work students [4,21,29].

Personality Type

Personality type was measured using the Ten Item Personality Measure (TIPI) [46]. This is an abbreviated version of the Big-Five instruments [47,48]. It is good for research that is conscientious of participant time constraints. Participants rate themselves on a 7-point Likert scale (disagree strongly to agree strongly) that asks them to describe themselves. The questions focus on their level of extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and the degree to which they are open to new experiences [46]. TIPI test-retest correlations are suitable (mean = .72). The TIPI has been used on undergraduate students in previous studies [49,50].

Civic Attitude

The variable civic attitude was constructed using five items designed to measure a participant’s civic beliefs and knowledge. A five-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree” was used to measure this construct. Three civic belief questions were asked; (1) “I believe it is important to vote,” (2) “I believe that it is important to belong to organizations that combat social injustices,” and (3) “I believe that it is important to participate in activities designed to combat social injustices.” Two civic knowledge questions were asked; (1) “I stay informed about social injustice occurring locally, regionally, and or in the United States” and (2) “I stay informed about national news and public issues.”

Moral Identity

To understand participants’ likelihood to engage in social activism it was important to understand internal characteristics that motivate individuals to participate in helping activities. The ten-item Moral Identity Measure was used to measure this [51]. The measure lists the characteristics caring, compassionate, fair, friendly, generous, helpful, hardworking, honest, and kind and asks the participant to rate themselves on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” about how important these characteristics are for a person to exhibit [51]. This measure was validated on university students and is reliable (α = .83) [52,53]. A previous study using this instrument found that people with higher levels of moral identity were more likely to engage in volunteerism [52]. Since the terms volunteerism and social activism are used interchangeably [44], the researchers felt this was an appropriate measure to incorporate into this model.

Opportunity

Three questions were used to measure a participant’s opportunity to engage in social activism. A five-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree” was used to measure this construct. The opportunity questions asked included (1) “I attend educational events that focus on populations that experience social injustices,” (2) “I vote in local and national elections,” and (3) “Through the years, I have belonged to an organization that challenges injustice.”

Social Activism

A participant’s level of social activism was measured through ten items. The items chosen for this construct were developed thinking about the continuum of activism activities that a person can participate. A five-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree” was used to measure this construct. For example, a participant in this research could have engaged in something as simple as “I have addressed social injustice by responding/sharing/ posting about issues of social injustice on social media” to something as complicated as “I have addressed social injustice by planning or holding an activity that challenges injustice.” The researchers felt it was important to list a continuum of social justice activities to capture all participants that engaged in activism.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Prior to conducting statistical analyses, the data were screened to assess accuracy, missing data, outliers, and the violation of assumptions. The data began with 224 participants before screening. The data was found to be accurate; however, the demographic questions were regrouped due to limited group sample sizes. Forty participants were excluded for missing more than five percent of their data and data was replaced using the “mice” package in R for 40 participants who were missing less than five percent of their data [54]. Assumptions of additivity, normality, linearity, homogeneity, and homoscedasticity were met. After excluding missing data and outliers, the sample size was 176 participants.

Statistical Analysis

Structural equation modeling was performed to test a model of direct and indirect influences, related to psycho-social factors, on social activism.

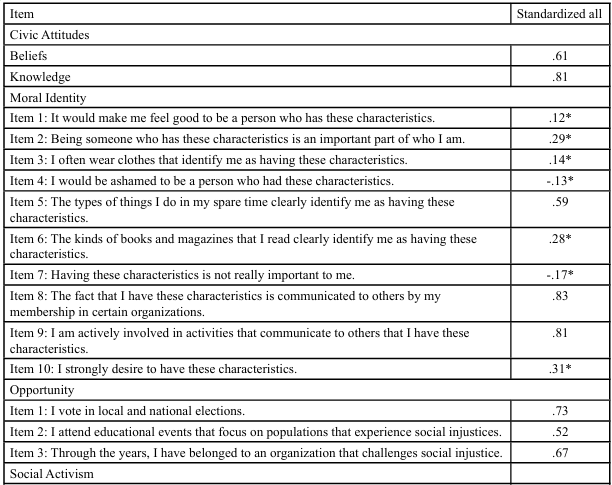

Step 1: Measurement Model

Prior to assessing the full structural equation model (SEM), the four latent variables were assessed: Civic Attitudes, Moral Identity, Opportunity, and Social Activism. The factor loadings for each manifest variable, within the constructs, were assessed to examine if the items were “good” items. The standard criteria for a loading is a value greater than 0.3 [55,56]. Using this criterion, seven items on the Moral Identity construct had poor loadings: item 1, item 2, item 3, item 4, item 6, item 7, and item 10. The seven items were removed from the model and the model was re-examined. Removing the bad items significantly improved the model (Δχ2 = 669.62, Δdf = 140, p < .001), however, model fit remained poor, χ2(129) = 343.50, p < .001, RMSEA = .10 [.85-.11], SRMR = .08, CFI = .84, NFI = .77, TLI = .81.

Step 2: Mediating (indirect) Effects Model

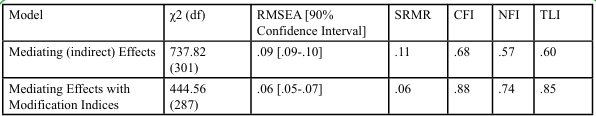

The next model postulates personality factors and social structure indirectly predicting social activism and are mediated by the beliefs, knowledge, moral identity, and opportunity variables. Due to model fit error, the Beliefs (average of three items) and Knowledge (average of two items) scales were included as individual manifest variables as opposed to the Civic Attitudes latent variable. The variables comprised of the personality and social structure constructs were also included in the model individually as manifest variables. The path model of the relationship between personality, social structure, beliefs, knowledge, moral identity, opportunity, and social activism was analyzed using maximum likelihood estimation. According to the fit indices, the model was poor.

Step 3: Mediating Effects Model with Modification Indices

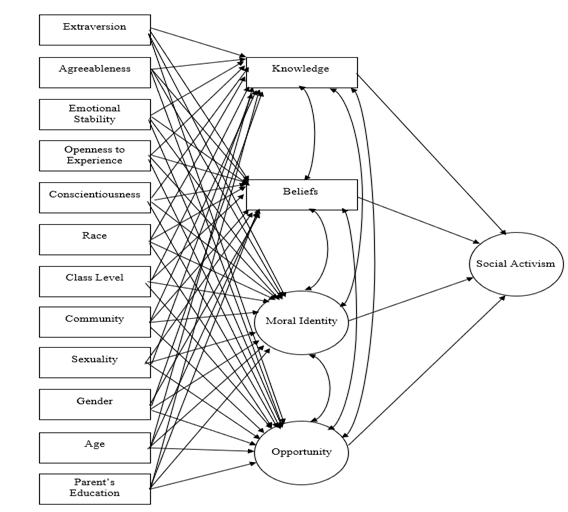

The next step assessed the modification indices of the mediating effects model (Figure 1). New paths were added to the model to improve the fit. The updated model included a correlation path between Beliefs and Knowledge, Beliefs and Moral Identity, Beliefs and Opportunity, Knowledge and Moral Identity, Knowledge and Opportunity, and Moral Identity and Opportunity. Adding the additional paths makes theoretical sense. The model produced a significant improvement in fit with the addition of the modification indices (Δχ2 = 293.26, Δdf = 14, p < .001). However, according to the fit indices of the final model, the goodness of fit indices appeared to be poor while the residual indices were excellent suggesting an improved, moderate model fit (Table 2).

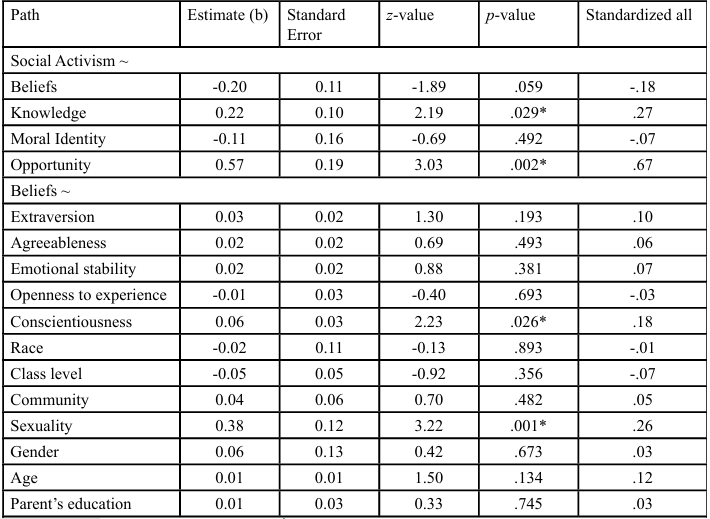

Parameter estimates were utilized to assess the paths in the model. According to the parameter estimates, a few of the paths were statistically significant (Table 3). Consistent with our hypothesis, the latent variable of Opportunity (p = .001) and the Knowledge manifest variable (p = .029) significantly predicted Social Activism. The latent variable of Moral Identity and the manifest variable of Beliefs did not significantly predict Social Activism. Personality factors and social structure showed a few significant indirect paths as well.

The final model (denoted in step 3) is described in which social activism was hypothesized to be the result of personality, social structure, moral identity, civic values and knowledge and social activism opportunities. The results from structural equation modeling suggest that the hypothetical model provides a moderate fit to the data. The tables and figures below provide a detailed overview of this.

Discussion

The lack of research conducted to understand personality and social structure characteristics associated with students’ engagement in social activism supports the need for further inquiry [25]. The current study contributed to this understanding by creating a model that described the psycho-social influences on BSW students’ commitment to social activism. The model hypothesized personality and social structure would predict civic attitudes, moral identity, and opportunity which would predict social activism; the model showed that opportunity and civic knowledge significantly predicted activism among the participants, with the model showing a moderate fit. This model was based upon Matsuba and colleagues [41] commitment to volunteering model. It also supported the use of social cognitive theory, by suggesting that student's ability to engage in social activism and their commitment to these activities were based upon individual psycho-social differences.

Three limitations should be noted about this study. Collecting data through a survey was the first limitation. Survey distribution took place in one large public university’s BSW program. Most of the students sampled were from the Midwest; therefore, this sample may not be representative of other BSW students across the United States. Second, the sample size was small to conduct structural equation modeling. Fritz and MacKinnon [57] note that an average sample size to determine model fit with structural equation modeling (SEM) is over 300 participants. This study was short of this target, and this impacted the ability to evaluate model fit utilizing SEM. Finally, some constructs (i.e., latent variables) were measured by a small number of manifest variables.

Understanding BSW students’ commitment to social activism has multiple implications for social work educators and professionals. CSWE requires BSW students to demonstrate their engagement in social activism activities. BSW programs have struggled developing social justice curricula [6,18] and finding ways to engage students in social justice activities [19]. This model suggests that personality is important to factor into students' willingness and motivation for social activism. This makes sense, as some students tend to be more inclined to engage in social activism than others. This aligns with students' desires or goals to practice on certain levels of social work. It is important to take this into consideration when attempting to engage all students in activism efforts; while all students can and should be involved, it may take more effort to ascertain unique ways to include students that may be less inclined to seek out activism opportunities. Additionally, personality is important to consider when developing social justice curricula to ensure inclusion of all social work students in their understanding of concepts as well as the importance of activism, and how activism can include a variety of roles and tasks for all to be involved.

Due to inconsistencies of the model fit indices, more research needs to be completed to further explore these findings and the influences on social activism. Additionally, as culture evolves, the model used to measure social activism should be continually revisited to ensure it addresses the current social issues surrounding activism and ask students how they define social activism. Utilizing a qualitative method to explore social activism may be important to dig deeper into this phenomenon and best meet the needs of students to ensure curriculum and programs expound on social worker’s mandate to engage in social justice. This model can shape future research and curriculum design focused on preparation for BSW educators and social work students as they prepare to learn about and engage in social activism. Identifying how educators can better assist students to be advocates in macro-level social work practice is immensely beneficial to the social work profession and macro social work.

Competing Interests:

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

Council on Social Work Education. (2022). Educational policy and accreditation standards. View

National Association of Social Workers. (2021). Code of ethics of the National Association of Social Workers. Washington, DC: NASW Press. View

Hoefer, R. (2019). Advocacy practice for social justice. Oxford University Press. View

Dodd, S. J., & Mizrahi, T. (2017). Activism before and after graduate education: Perspectives from three cohorts of MSW students. Journal of Social Work Education, 53(3), 503-519. View

Bent-Goodley, T.B. (2015). A call for social work activism. Social Work, 60(2), 101-103. View

Benner, K., Loeffler, D., & Buchanan, S. (2019). Understanding social justice engagement in social work curriculum. The Journal of Baccalaureate Social Work, 24(1), 321-337. View

Lee, E., Kourgiantakis, T., Hu, R., Greenblatt, A., & Logan, J. (2022). Pedagogical methods of teaching social justice in social work: A scoping review. Research on Social Work Practice, 32(7), 762-783. View

Mehrotra, G. R., Hudson, K. D., & Self, J. M. (2017). What are we teaching in diversity and social justice courses? A qualitative content analysis of MSW syllabi. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 37, 218-233. View

Abramovitz, M. (1998). Social work and social reform: An arena of struggle. Social Work, 43(6), 512-526. View

Jeyapal, D. (2017). The evolving politics of race and social work activism: A call across borders. Social Work, 62(1), 45-52. View

Buila, S. (2010). The NASW Code of Ethics under attack: A manifestation of the culture war within the profession of social work. Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics, 7(2). View

Mizrahi, T., & Davis, L. (2008). The encyclopedia of social work, 20. Oxford Press. View

Bryson, S. A., Mehrotra, G., Rodriguez-JenKins, J., & Ilea, P. (2022). Centering racial equity in a BSW program: What we’ve learned in five years. Journal of Social Work Education, 60 (1), 27-42. View

Gabel, S., & Mapp, S. (2020). Teaching human rights and social justice in social work education. Journal of Social Work Education, 56(3), 428-441. View

Nicotera, A. (2019). Social justice and social work, a fierce urgency: Recommendations for social work social justice pedagogy. Journal of Social Work Education, 55(3), 460-475. View

Reed, B. G., & Lehning, A. J. (2014). Educating social work students about social justice practice. In M. J. Austin (Ed.), Social justice and social work: Rediscovering a core value of the profession (pp. 339-356). SAGE Publications. View

Hightower, L., & Johnson, K. E. (2019). The importance of diversity and social justice in BSW programs: Implications for social work education in the U.S. The Hong Kong Journal of Social Work, 53(2), 47-66. View

Gutierrez, L., Fredricksen, K., & Soifer, S. (1999). Perspectives of social work faculty on diversity and societal oppression content: Results from a national survey. Journal of Social Work Education, 35, 409-419. View

Knight, C. (2017). BSW and MSW students’ opinions about and responses to the death of Freddie Gray and the ensuing riots: Implications for the social justice emphasis in social work education. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 37(1), 3-19. View

Edmonds-Cady, C., & Wingfield, T.T. (2017). Social workers: Agents of change or agents of oppression? Social Work Education, 36(4), 430-442. View

Bernklau Halvor, C. D. (2016). Increasing social work students’ political interest and efficacy. Journal of Policy Practice, 15(4), 289-313. View

Jacob, A., & Bentley, K. J. (2023). Teaching BSW students to apply the grand challenges in social work through field based research projects. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 43(2), 239-252. View

Morrison Van Voorhis, R., & Hostetter, C. (2006). The impact of MSW education on social worker empowerment and commitment to client empowerment through social justice advocacy. Journal of Social Work Education, 42, 105-121. View

Van Soest, D. (1996). Impact of social work education on student attitudes and behavior concerning oppression. Journal of Social Work Education, 32, 191-202. View

Krings, A., Trubey-Hockman, C., Dentato, M. & Grossman, S. (2019). Recalibrating micro and macro social work: student perceptions of social action. Social Work Education, 39(2), 160 174. View

Dodd, P., & Gutierrez, L. (1990). Preparing students for the future: A power perspective on community practice. Administrative in Social Work, 14, 63-78. View

Weiss, I. (2006). Modes of practice and the dual mission of social work: A cross-national study of social work students’ preferences. Journal of Social Service Research, 32, 135-151. View

Golden, J. C. (2023). Social work and social justice advocacy: a survey of BSW students’ attitudes and perceptions. Social Work Education, 43(9), 2754-2773. View

Bhuyan, R., Bejan, R., & Jeyapel, D. (2017). Social workers’ perspectives on social justice in social work education: When mainstreaming social justice masks structural inequalities. Social Work Education, 36(4), 373-390. View

Abramovitz, M., & Sherraden, M. (2016). Case to cause: Back to the future. Journal of Social Work Education, 1-10. View

Harrison, J., VanDeusen, K., & Way, I. (2016). Embedding social justice within micro social work curricula. Smith College Studies in Social Work, 86(3), 258–273. View

Mattocks, N. (2018). Social action among social work practitioners: Examining the micro-macro divide. Social Work, 63(1), 7-16. View

Atteberry-Ash, B., Swank, E., & Williams, J. R. (2023). Sexual identities and political protesting among social work students. Journal of Policy Practice and Research, 4, 117-135. View

Deeb-Sossa, N., Manzo, R., Aranda, A., & Kelty, J. S. (2024). Cultivating university students’ critical sense of belonging through community-responsive scholar-activism. Collaborations: A Journal of Community-Based Research and Practice, 7(1), Article 2. View

Reeser, L., & Epstein, I. (1990). Professionalization and activism in social work: the sixties, the Eighties, and the future. Columbia University Press. View

Richards-Schuster, K., Espitia, N., & Rodems, R. (2019) Exploring values and actions: Definitions of social justice and the civic engagement of undergraduate students. Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics, 16(1), 27-38. View

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall. View

Bandura, A. (2005). The evolution of social cognitive theory. In K. G. Smith and M.A. Hitt (Eds.), Great Minds in Management (pp. 9-35). Oxford University Press. View

Miller, M. J., Sendrowitz, K., Connacher, C., Blanco, S., Muniz de la Pena, C., Bernardi, S., & Morere, L. (2009). College students’ social justice interest and commitment: A social cognitive perspective. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56, 495-507. View

Miller, M. J., Sendrowitz, & Sendrowitz, K. (2011). Counselig psychology trainees’ social justice interest and commitment. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58(2), 159-169. View

Matsuba, M.K., Hart, D., Atkins, R. (2007). Psychological and social-structural influences on commitment to volunteering. Journal of Research in Personality, 41. 899-907. View

Henriksen, L., & Svedberg, L. (2010). Volunteering and Social Activism: Moving beyond the Traditional Divide. Journal of Civil Society, 6(2), 95–98. View

Wilson, J. (2000). Volunteering. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 215-240. View

Bales, K. (1996). Measuring the propensity to volunteer. Social Policy & Administration, 30(3), 206–226. View

Janoski, T. (2010). The dynamic processes of volunteering in civil society: A group and multi-level approach. Journal of Civil Society, 6(2), 99–118. View

Gosling, S. D., Rentfrow, P. J., & Swann, Jr., W. B. (2003). A very brief measure of the big-five personality domains. Journal of Research in Personality, 37, 504-528. View

Costa, P. T., Jr., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO FiveFactor Inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources. View

Goldberg, L. R. (1992). The development of markers for the big-five factor structure. Psychological Assessment, 4, 26–42. View

Brown, T., Williams, B., & Etherington, J. (2016). Emotional intelligence and personality traits as predictors of occupational therapy students’ practice education performance: A cross sectional study. Occupational Therapy International, 23(4), 412-424. View

Ispir, O, Elibol, E. & Sönmez, B. (2019). The relationship of personality traits and entrepreneurship tendences with career adaptability of nursing students. Nurse Education Today, 79, 41-47. View

Reed, II, A., Aquino, K., & Levy, E. (2007). Moral identity and judgements of charitable behaviors. Journal of Marketing, 71, 178-193. View

Aquino, K., & Reed, A. (2002). The self-importance of moral identity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(6), 1423-1440. View

Reed, A., & Aquino, K. (2003). Moral identity and the expanding circle of moral regard toward out-groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(6), 1270-1286. View

Van Buuren, S., & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. (2011). Mice: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. Journal of Statistical Software, 45(3), 1-67. View

Cheung, G. W., Cooper-Thomas, H. D., Lau, R. S., & Wang, L. C. (2024). Reporting reliability, convergent and discriminant validity with structural equation modeling: A review and best- practice recommendations. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 41, 745-783. View

Ondé, D., & Alvarado, J. M. (2018). Scale validation conducting confirmatory factor analysis: A Monte-Carlo simulation study with LISREL. Frontiers in Psychology, 9(751). View

Fritz, M. S., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2007). Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science, 18(3), 233-239. View