Journal of Social Work and Welfare Policy Volume 3 (2025), Article ID: JSWWP-171

https://doi.org/10.33790/jswwp1100171Research Article

Does Context Change the Story? Gender Differences in Reporting Intimate Partner Violence Among College Students

Hyunkag Cho1*, PhD., Jisuk Seon2, PhD., Y. Joon Choi3, PhD., Ga-Young Choi4, PhD., Ilan Kwon5, PhD.,

1School of Social Work, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, United States.

2Department of Social Welfare, Kyungnam University, Changwon, Republic of Korea.

3School of Social Work, Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA, United States.

4School of Social Work, California State University Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States.

5Worden School of Social Service, Our Lady of the Lake University, San Antonio, TX, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Hyunkag Cho, PhD., School of Social Work, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, United States.

Received date: 23rd October, 2025

Accepted date: 24th November, 2025

Published date: 26th November, 2025

Citation: Cho, H., Seon, J., Choi, J., Choi, G. Y., & Kwon, I., (2025). Does Context Change the Story? Gender Differences in Reporting Intimate Partner Violence Among College Students. J Soci Work Welf Policy, 3(2): 171.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

This study examines how contextual framing influences self reported experiences of intimate partner violence (IPV) and potential gender differences in reporting patterns. A web-based survey of 163 U.S. college students randomly assigned to a contextualized or non-contextualized version of an IPV measure was analyzed using chi-square tests and logistic regression. Results indicated that including contextual qualifiers (e.g., excluding joking or playful behavior) affected reporting patterns, with higher psychological IPV victimization reported under contextualized conditions and gender differences observed in victimization rates. These findings underscore the importance of contextual interpretation in measuring IPV and suggest that gender disparities in prevalence estimates may partly reflect differences in how individuals perceive and report aggressive behaviors.

Keywords: Intimate Partner Violence; College; Victims; Perpetrators; Gender-Based Violence

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a serious social problem that results in numerous negative consequences for the survivors. IPV is abuse or aggression that occurs in an intimate relationship, such as current or former spouses and dating partners, and can include physical, sexual, and psychological violence. Some studies suggest that IPV is predominantly violence against women [1], while research results on gender differences in IPV prevalence in both victimization and perpetration rates have been inconsistent. Unlike what is commonly assumed, some found similar IPV victimization rates between men and women [2]; some found even higher victimization prevalence among men than women [3]. Similarly, some studies have reported conflicting research findings on IPV perpetration rates, ranging from equal perpetration rates between men and women [4] to higher perpetration rates among women [5] or men [6] compared with their counterparts.

While methodological differences across studies have been widely suggested as the potential source for such discrepancies, another possible explanation is that IPV takes place in different contexts across gender. For example, partners may engage in horseplay that one views as harmless fun, while the other perceives it as physical aggression. One of them, who might also have been exposed to other intimidating behaviors by the partner, may interpret the partner’s acts during horseplay as violent and scary, while the other partner may not share such a view. Models of measurement bias have explained such gender differences as reflecting, at least in part, differences in how IPV is measured rather than in actual experiences [7,8]. The inconsistent findings reported in past studies make it important to examine the relationships between gender and the contexts in which IPV occurs. Such research takes on even greater importance because the findings could affect resource allocations as well as policies and practices concerning IPV [1,6,9]. This study attempts to address the potential gender difference that the contexts of IPV make to the reporting of IPV prevalence, using a sample of college students. The IPV perpetration and victimization rates tend to surge between the late teens and early 20s [10,11], and the age range overlaps with that of the majority of college-enrolled young adults (18-24 years old) [12]. While similar IPV prevalence rates between college enrolled and non-enrolled young adults have been reported [13,14], studies also have demonstrated the negative impact of IPV on college students, concerning health and mental health [15-18] as well as their academic performances [19]. Therefore, understanding and addressing IPV among college students can be critical in preventing and reducing IPV for their health and successful educational achievement.

Literature Review

Gender Differences in IPV Prevalence

Victimization Rates

National studies tend to report higher IPV victimization rates among women than men in general, although, in some national data, the gender gap in the victimization rates seems to be minimal. Studies using U.S. National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) data have consistently shown higher female victimization rates [20,21]. The NCVS collects annual data on the nonfatal victimization experiences of people aged 12 years or older. Nonfatal victimization includes rape, sexual assault, robbery, and aggravated and simple assaults. From 1993 to 2010, the average nonfatal IPV victimization rate among women by former and current partners was 5.6 times higher than that of men (9.56% versus 1.69% [22]). Furthermore, the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey [23] reported that lifetime experiences of IPV were higher among women, although the rate among men was only slightly lower; and their IPV prevalence in the previous 12 months was almost identical. However, the number of women who experienced sexual violence compared to men was more than double.

Research based on college samples seems to report inconsistent results. Some studies showed that women were victimized by IPV more than men. In a study based on the NCVS data collected from 1995 to 2013, Rennison and Addington [21] found that female college students were noticeably more likely to experience IPV victimization than male students regardless of the types of IPV. Although not much of a gender gap was observed in rape or sexual assault victimization experiences perpetrated by their intimate partners (38.9% men and 32.9% women), the percentage of simple assault type of IPV was significantly more frequently reported by women (33.9% vs. 46.1%). Likewise, another study reported that more women than men were victimized by physical and sexual violence during their university years by their intimate partners [24]. However, another group of studies reported differently. Psychological victimization rates of men were found to be slightly higher than those of women [24,25]. Chan et al. [26] found that more male college students were victims of physical assault; unlike national survey research such as NISVS and NCVS, Chan and his colleagues also reported a higher sexual violence victimization rate (more specifically, sexual coercion) among men than women by their intimate partners.

Perpetration Rates

Several nationally representative studies have reported women perpetrating IPV more frequently than men do [27-29]. Schwab Reese et al. [28] reported that more women were likely to perpetrate than men, using the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health) data collected in 2008 when the adolescent cohort were in the ages of between 24 and 32. Women indicated a higher significant number of IPV perpetration across all measured types of IPV compared to men (i.e. threats/minor physical IPV and severe physical IPV), although more men reported causing injury to their partners due to their physical perpetration [28]. Likewise, using a national sample, Okuda et al. [27] found that women generally reported IPV perpetration at significantly higher rates than men in the past year; however, men were more likely to be involved in sexual perpetration than women.

Several studies that focused on college students seem to suggest some gender gaps in IPV perpetration. In one study, more women than men (18%) college students reported exhibiting physically violent behaviors toward their dating partners [25]. In another study, psychological aggression toward intimate partners was more frequently reported by female students than male students [4]. However, patterns can vary by the type of violence. One study found that female students reported higher rates of physical violence perpetration than male students (8%), whereas male students reported higher rates of sexual violence perpetration than female students (16.8%), with no significant gender differences observed in psychological violence perpetration [30].

Despite the inconsistent findings on the IPV prevalence rates among men and women, studies have consistently shown more negative impacts of IPV on women than men [31]. Women experience higher injury rates than men [31,32]; this is the case even when women are the perpetrators of IPV [28,31]. Among IPV victims, more women than men reported an increased likelihood of experiencing mental health problems such as depression, panic attacks, heavy alcohol use, eating problems, suicide ideation and attempts, and negative perceptions of their health [33]. Having experienced coercive control in the previous year also was more related to poor or fair self-reported mental health among women than men [34].

Contexts of IPV and Gender Differences

Researchers have suggested that such discrepant study outcomes in gender differences in IPV victimization and perpetration rates result from methodological issues and various contexts of IPV across gender [35-39]. For instance, the scales that produced gender symmetry (i.e., similar IPV rates between women and men) might have used simple behavioral checklists, which omits assessing specific incidental contexts, whereas the IPV instruments that result in gender asymmetry tend to have questions that inquire about the details of the context in which IPV occurred [37,38]. The IPV victimization rates from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) before and after revising the survey questionnaire are a good example of how measurements can affect responses [37]. Until 2012, the YRBS had only one item that tapped into physical violence (“During the past 12 months, did your boyfriend or girlfriend ever hit, slap, or physically hurt you on purpose?”). This item raised a concern among experts as adolescents’ horseplay acts were likely to be counted, and whether the violent physical act (hit, slap, or hurt) was purposefully done was unclear [40]. In fact, a study with adolescents showed that both males and females tend to report higher rates of physical aggression perpetration and victimization experiences in dating relationships in joking contexts than non-joking contexts [41]. In 2013, the YRBS was modified to include expressions such as “physically hurt you on purpose” and “force you to do sexual things that you did not want to,” which more “carefully operationalize the elements of intent, unwantedness, and harm that are essential components of violence” [37]. After this modification, female victimization rates drastically increased from 9% to 20.9%, although male victimization rates remained unchanged.

Some measurements seem to produce over-reporting or false positive IPV rates, with men being likely to over-report their IPV victimization experiences. Ackerman [35] tested gender difference in over-reporting IPV victimization using the Conflict Tactic Scale (CTS) and follow-up questions to explore whether a violent act the respondent reported was an intended violent incident or an event that both partners did not take seriously. In this study, although both men and women over-reported their victimization experiences, the over reporting rates of men were almost double those of women (23.4% vs. 12.9%).

However, it seems also possible that less reporting of IPV could happen depending on the perceptions and context of IPV. For example, minimizing sexual assault victimization incidents were common among college survivors of sexual assault across all genders [42]. College students who displayed minimizing beliefs generally perceived their sexual assault victimization was not ‘bad enough’ or ‘not serious enough’ to be considered sexual violence, or that ‘it was normal’ to experience sexual assault as it happened frequently among their peer groups; as such, they did not report the incidents to authorities or helping professionals [42]. In addition, Wood and Toppelberg [43] reported that male sexual assault victims in the military were likely to have multiple perpetrators in a form of hazing. While IPV is not identical to hazing, a similar pattern might exist in that both forms of violent treatment against others are normalized and permitted by a larger group the victims are part of. Then, perpetrators might not perceive their abusive behaviors as IPV, which subsequently could lead to lower reporting rates of IPV perpetration.

Method

The Current Study

Considering the gendered reporting of IPV victimization and perpetration and answering the call by Ackerman [35] to test the gendered reporting, the current research examined whether self reported IPV perpetration and victimization rates were different by gender, depending on the inclusion of a contextual qualifier in the survey items. In IPV survey items with a contextual qualifier, a specific context in which IPV perpetration and victimization occurred is described. The contextual qualifier used in the current study was “Not including horseplay or joking around” whether the college students engaged in IPV- perpetrating acts or were violently treated by their partners (see the Method section for details). Specific research questions of this study were as follows.

1. Gender Differences in IPV Reporting:

1-1. Do IPV perpetration rates differ by gender?

1-2. Do IPV victimization rates differ by gender?

2. Effects of Contextual Qualifiers on IPV Reporting:

2-1. Do IPV perpetration rates differ depending on whether the questions include a contextual qualifier?

2-2. Do IPV victimization rates differ depending on whether the questions include a contextual qualifier?

3. Interaction Between Gender and Contextualization:

3-1. Among students who responded to questions with a contextual qualifier, do IPV perpetration rates differ by gender?

3-2. Among students who responded to questions without a contextual qualifier, do IPV victimization rates differ by gender?

4. Combined Effects of Gender and Question Context:

4-1. How are gender and the inclusion of a contextual qualifier in survey items associated with reporting IPV perpetration?

4-2. How are gender and the inclusion of a contextual qualifier in survey items associated with reporting IPV victimization?

Study sample and procedure

This study used a cross-sectional research design, for which a self administered survey was created and launched in an online survey platform (i.e., SurveyMonkey), pilot tested and distributed to the sample in April 2016. A convenience sample was drawn from a Midwest public university in the U.S., through an email with a brief introduction of the survey, an informed consent letter, and a separate link to win small incentives (i.e., a raffle for $50 Amanzon.com gift cards). Students who reported during the screening questions that they had been married or in a romantic relationship at least one month long were eligible to participate in the survey. A total of 272 surveys were returned; our final sample size was 163, removing the respondents who did not answer the major variables of our interest, such as gender, race, and IPV questions about victimization and perpetration.

Measures

IPV victimization. IPV victimization assessed three different types of victimization such as psychological, physical, and sexual victimization, which was created based on two existing IPV instruments. Questions on physical and sexual violence were adopted from the Partner Victimization Scale [36]. Psychological violence questions were from Ansara and Hindin [44]. Participants were asked whether they had ever experienced such violence from their current or previous romantic partners, including boyfriends, girlfriends, husbands, wives, and ex-partners. It consisted of 12 question items (Cronbach’s alpha=0.92), including eight items for psychological violence (e.g., My partner threatened to hurt me and I thought I might really get hurt), three items for physical violence (e.g., My partner pushed, grabbed, or shook me), and one item for sexual violence (e.g., My partner made me do sexual things when I did not want to). Each item was rated based on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0= Never to 4= Four times or more. The sum of each type of IPV was calculated to create three dichotomous variables, representing physical, psychological, and sexual violence victimization (0= no victimization; 1=at least one victimization). Another variable of “Any IPV Victimization” was created to indicate if a participant was victimized by any of the three types of IPV (0= no victimization; 1=at least one type of victimization).

IPV perpetration. IPV perpetration measured three types of IPV perpetration using the same questions as IPV victimization (Cronbach’s alpha=0.95), with some wording changed to indicate perpetration (e.g., “I threatened to hurt my partner” instead of “My partner threatened to hurt me”). The sum of each type of IPV perpetration was converted to three dichotomous variables, representing physical, psychological, and sexual violence perpetration (0= no perpetration and 1= at least one perpetration). An “Any IPV Perpetration” variable was created to indicate if a participant perpetrated any of the three types of IPV (0= no perpetration; 1=at least one type of perpetration).

Contextual or non-contextual IPV questions. Participants responded to survey questions for IPV victimization and perpetration either with contextual or non-contextual questions. The situational context of IPV was intended to help the participants determine whether certain behaviors were viewed as a violent act under certain circumstances, expecting that the situational context would affect the participants’ responses to the victimization and perpetration questions. All survey participants were directed to a question asking, “Which color would you choose?” with two response options (e.g., red or blue) prior to answering IPV victimization questions, and were asked again prior to perpetration questions. If the participants marked a certain color (e.g., red), they were assigned to the IPV questions containing the context of the IPV situation. This was to randomize the participants to either the contextual or non-contextual questions as such a function was not available in the version of SurveyMonkey used for this study. In the survey, a contextual phrase, “Not including horseplay or joking around,” was added to one psychological and three physical violence questions. The contextual qualifier was not added to a sexual violence question or to seven additional psychological violence questions, as the contextual information was not considered relevant to them. In other words, survivors are likely to consider some psychologically violent acts (e.g., My partner harmed or threatened to harm someone close to me) and sexually violent acts (e.g., My partner made me do sexual things when I did not want to) as very serious, thus unlikely to interpret them as part of horseplay or joking around. An exemplar contextual question is “Not including horseplay or joking around, my partner pushed, grabbed, or shook me.” Participants who picked the other color (e.g., blue) were assigned to those IPV questions with no contextual qualifier (e.g., My partner pushed, grabbed, or shook me).

Demographic characteristics. Gender was measured by asking if the participants were women, men, or other. Two participants who identified themselves as other were excluded in the analyses. Race/ethnicity was measured by eight categories (e.g., “Asian, Pacific Islander, “Black, African American,” “Hispanic,” “Spanish, Hispanic, Latino,” “White, Caucasian, European,” “American Indian, Native American, Native Canadian, First Nations,” “Multi-Ethnic,” and “Other”), but due to some categories’ small sizes, reduced to two categories for this study: White and non-White. Grade level had five categories (e.g., “Freshman,” “Sophomore,” “Junior,” “Senior,” and “Other”). Age was measured in years as a continuous variable.

Analyses

First, sample characteristics were described, including gender, race, and age. Next, we ran Pearson’s chi-square tests to examine whether there were differences in reporting IPV perpetration and victimization by gender and inclusion of a contextual qualifier in the survey items (Research Questions 1, 2, & 3). In addition to the chi-square tests, Fisher’s exact tests were computed when the expected number of frequencies in contingency tables (cross tabulations) was less than five. For both chi-square tests and Fisher’s exact tests, a Bonferroni correction was applied to control for inflated Type I error due to multiple comparisons between groups (i.e., women vs. men, contextual vs. non-contextual) for IPV victimization and perpetration. Accordingly, we adjusted the significance level to p < .00625 by dividing the standard p = .05 by the total of eight tests conducted for each analysis. Last, we ran multiple logistic regressions with IPV perpetration and IPV victimization as the dependent variables to examine if gender and inclusion of a contextual qualifier in the survey items are associated with reporting IPV (Research Question 4). SPSS v.22 was used for all analyses.

Results

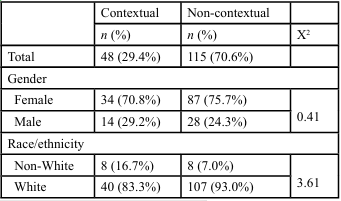

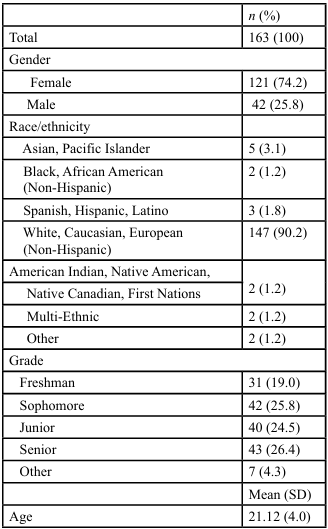

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the sample. Out of 163 sampled, the vast majority of survey participants were women (74.2%) and white (90.2%). The students were distributed across grade levels, with the highest proportion in the senior year (26.4%), followed by the junior year (25.8%) and the freshman year (24.5%). Their mean age was approximately 21 years old.

In assigning colors to contextual and non-contextual questions, 48 participants were assigned to contextual questions and 115 to non-contextual questions. No significant differences were found between the groups.

Table 1-1: Demographic differences between students answering contextual or non-contextual questions

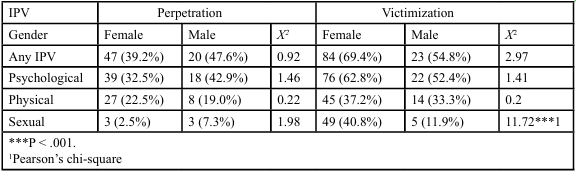

Table 2 displays gender differences in reporting IPV perpetration and victimization. There were no significant gender differences in reporting IPV perpetration between women and men. Regarding IPV victimization, sexual violence victimization showed a significant gender difference (women 40.8% vs. men 11.9%, X2(1) = 11.72, p < .001), indicating that more female than male students reported experiencing sexual violence victimization. The result remained statistically significant even after applying the Bonferroni correction (adjusted p = .00625). No other significant gender differences were found for IPV victimization.

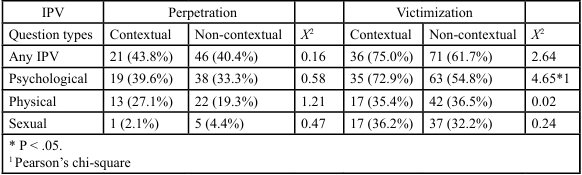

Table 3 represents differences in reporting IPV perpetration and victimization depending on inclusion of a contextual qualifier in the survey items. No significant differences were found in reporting IPV perpetration between survey items with or without a contextual qualifier. As for victimization, psychological violence victimization showed a significant difference between survey items with or without a contextual qualifier (contextual 72.9% vs. non-contextual 54.8%, X2(1) = 4.65, p =.04). However, after applying the Bonferroni correction (adjusted p = .00625), the result was no longer statistically significant.

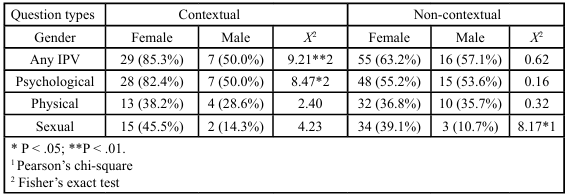

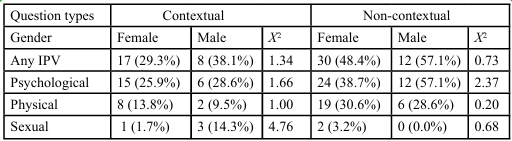

Table 4 describes the gender difference in reporting IPV perpetration depending on contextual or non-contextual questions. None of the gender differences in reporting both IPV perpetration and victimization based on contextual versus non-contextual questioning were statistically significant.

Table 4-1: Gender differences in reporting IPV perpetration depending on contextual or non-contextual questions

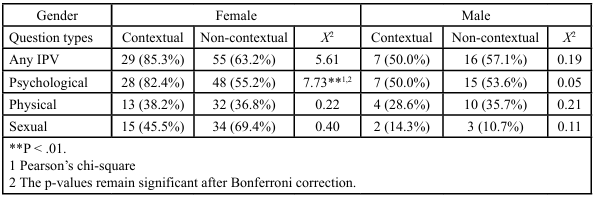

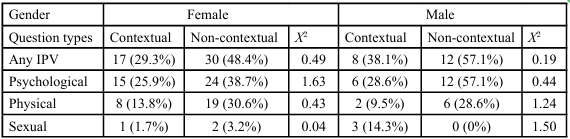

Furthermore, no statistically significant differences were found in reports of IPV perpetration with and without contextual questions among women and men, respectively.

Table 4-2: Differences in reporting IPV perpetration with and without contextual questions among women and men

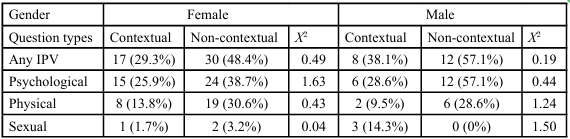

Table 5 illustrates the gender differences in reporting IPV victimization depending on contextual or non-contextual questions. In the sample of students who responded to contextual questions, there were significant gender differences in reporting any IPV victimization (X2(1) = 9.21, p = .007) and psychological violence victimization (X2(1) = 8.47, p = .04). Both results were no longer considered statistically significant after applying the Bonferroni correction with a significance threshold of p < .00625.

Among those who responded to non-contextual questions, a significant gender difference was observed in reporting sexual violence victimization (female 39.1% vs. 10.7%, Χ2 (1) = 8.17, p = .03). However, after applying the Bonferroni correction (adjusted p = .00625), the result was no longer statistically significant. Moreover, since no contextual qualifier was applied to sexual violence victimization, the result reflects the gender difference among participants in the non-contextual group.

Table 5-1: Gender differences in reporting IPV victimization depending on contextual or non contextual questions

In terms of differences in reporting IPV victimization with and without contextual questions among women, psychological violence showed a significant difference (non-contextual: 63.2% vs. contextual: 36.8%, X²(1) = 7.73, p = .005), indicating that female students who responded to non-contextual items reported a higher percentage of psychological violence victimization. This result remained statistically significant even after applying the Bonferroni correction (adjusted p = .00625).

Table 5-2: Differences in reporting IPV victimization with and without contextual questions among women and men

Table 6 and Table 7 show if gender and inclusion of a contextual qualifier in the survey items are associated with reporting IPV perpetration and victimization, respectively. Gender showed a significant association; women are associated with an increase in the likelihood of reporting sexual violence victimization compared to men (OR = 6.365, 95% CI [2.085-19.436], p = .001). We further tested the interaction between gender and the contextual qualifier in a logistic regression model for sexual violence victimization. However, no significant results were found and, therefore, are not reported. In addition, age was associated with a higher likelihood of reporting physical violence victimization (OR = 1.102, 95% CI [0.972-1.219], p = .02).

Discussion

This study examined whether self-reported IPV perpetration and victimization rates were different between male and female college students. While perpetration rates were not different between men and women, victimization rates were much higher among women than men for sexual violence, which is consistent with several prior studies that used national data [20,45].

When comparing contextualized and non-contextualized assessments of IPV, perpetration rates were not different between the assessments; victimization rates of psychological violence were higher when assessed by contextualized questions than non-contextualized ones. This difference can be better understood by considering gender. A higher proportion of women reported any IPV in general, and specifically of psychological violence, than men when assessed by the contextualized questions. While it is hard to explain the reasons for such finding based on the study data, this result suggests that psychological IPV experienced by college students, especially female students, may be better captured with contextual qualifiers that indicate the purpose of the act in IPV assessments [35,36]. It is noteworthy that even though the contextual qualifier was added to just a single psychological violence question, the proportions of female students reporting psychological violence victimization were different from male students between contextualized and non-contextualized questions. It may be due to the order of the questions asked, with contextualized physical violence questions asked first, followed by non-contextualized sexual and psychological violence questions. The respondents might have responded to the non-contextualized questions under the assumption that they were also contextualized as with the physical violence questions. Future research needs to further examine the role and influence of contextualization of IPV questions by sophisticated methods that can reveal delicate interactions between the way questions are asked and respondents’ reporting.

In both contextual and non-contextual groups, more female students than male students reported experiencing sexual violence from their intimate partners; but only the non-contextual group showed a statistically significant gender difference. Although no context qualifier was added to a sexual violence question, as with psychological violence, the respondents might have answered as if it was also contextualized. Sexual IPV victimization rates of women compared to men tend to be higher in most of the national studies that did not use contextual qualifiers [20,23]. Our findings might reflect this general prevalence of sexual IPV victimization, yet it may be due to the small sample size of the contextual group (only 17 students in total, with two male students).

Both female and male students reported higher IPV perpetration in non-contextual questions in all types of IPV, although they were not significant. Women’s reports of victimization showed different patterns. Compared to the non-contextual female group, the contextual female group showed higher IPV victimization rates for psychological violence. This is consistent with previous studies [37,38]. That is, men overreported their victimization without the “no joke” qualifier, but women underreported IPV victimization without the “no joke” qualifier. These results suggest that the role of a contextual qualifier may differ depending on gender. There have been attempts to explain why there is a gendered pattern in over-reporting of IPV. Some have argued that men may report victimization that did not occur to depict themselves as victims to reduce blame and justify their own perpetration against partners [46]. Others argued that unintentional mechanisms are at play, in which survey participants interpret survey items that are different from the intent of survey developers [47]. Akerman [35] reported the association between increases in age and decreases in IPV over-reporting among college students. This suggests that individuals’ maturity may be related to their ability to interpret the intent of IPV items correctly. Studies show men mature slower than women emotionally, including a study of college students [48]. Then, male students’ lower maturity level might be related to their over-reporting of IPV victimization and perpetration. Theoretically, research using models of measurement bias indicates that some reported gender differences in IPV may reflect inconsistencies in measurement approaches instead of genuine disparities in lived IPV experiences [7,8]. Results from this study highlight the complex nature of gender differences in IPV measurement. Theories should be expanded to incorporate social, cultural, and psychological mechanisms that explain IPV across genders, recognizing various measurement biases and using advanced techniques to address them (e.g., confirmatory factor analysis, latent class models [8]).

Results from this study should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, women are overrepresented in this study (74% of the sample), considering the makeup of the student body at the study university. Relatedly, due to small subgroup sizes, certain gender identities (e.g., transgender and non-binary) were excluded from the analysis, and all non-White racial and ethnic categories (e.g., Black, Hispanic) were combined into a single category. This lack of a representative sample should be addressed by future research. Second, previous research has shown that study participants who found a study topic to be less relevant or threatening were less likely to participate [49], which suggests that response bias may have resulted in lower representation of students at either continuum of IPV perpetration and/or victimization. Third, although the contextual qualifier was not added to sexual and some psychological violence questions, horseplay might still be a factor for those questions. For instance, if a perpetrator grabs a survivor’s body part that can be considered private, the survivor may not be sure of whether that act is IPV or not, which may influence their reporting. Future research is needed to test this possibility. Fourth, a color question was used to randomize the participants, which did not work as expected (e.g., 48 participants assigned to the contextual questions and 115 to the non-contextual questions). Participants’ choice of color might have influenced their reporting for unknown reasons (e.g., gender, history of IPV). Unequal group sizes may have influenced the study findings, potentially leading to reduced statistical power and an inflated Type I error rate. Future research needs to use more sophisticated ways to randomize than a color choice. Fifth, social desirability might have affected the results of this study, considering the sensitive nature of disclosing IPV victimization or perpetration experiences. However, data in this study were collected through an anonymous online survey and past research has shown that study participants are more honest in their answers to online surveys than to other types of surveys [50]. Sixth, the assessment of sexual violence consisted of a single item for both IPV victimization and perpetration. Seventh, while this study relied solely on quantitative data, future research would benefit from incorporating qualitative methods to deepen understanding of how college students interpret and respond to IPV questions with or without contextual qualifiers. Qualitative data, such as interviews or open-ended survey responses, could help illuminate the meanings participants assign to their experiences and clarify the cognitive and emotional processes involved in identifying behaviors as violent. Such insights could complement quantitative findings and contribute to more nuanced interpretations of gender differences in IPV reporting. Finally, a sample from one university limits the generalizability of the findings.

Conclusion

IPV is a significant health issue for college students, and it is critical for institutions of higher education to address this problem. Since the recent governmental call for colleges to prevent and respond to sexual assault on campus and accompanying federal funding, most colleges have implemented sexual assault awareness training on campus [51]. The efforts by colleges to address IPV, however, have not been extensive [10]. This research has valuable implications for developing IPV prevention and intervention programs on college campuses. The findings show that contextual factors surrounding IPV incidents contribute to college students’ perceptions toward IPV victimization and perpetration, which in turn may impact their help- seeking behaviors. Students may not seek help if they do not realize that they are experiencing IPV. This points to the need to include the definition and coercive contexts of IPV in prevention and awareness training for college students. When students are aware of different types of IPV, as well as the coercive nature of IPV, it will help students identify their IPV victimization or perpetration.

For the institutions of higher education to properly respond to IPV on campus, a proper identification of IPV is essential, which requires asking the right screening and assessment questions. To accurately portray IPV rates across gender, IPV measurements need to assess the contexts of IPV, distinguishing serious and/or persistent IPV acts from incidental or horseplay types of IPV acts. When IPV scale items merely ask whether or not a particular act has occurred, survey respondents may not be able to differentiate them [37,38]. Using IPV scales sensitive to such contextual information is especially critical when surveying young adults, considering that they are in the developmental stage where they often experiment with boundaries with their partners through ‘joking around’ or ‘horseplay’ behaviors. This study mostly focused on the intent of acts, but “joking around” can be as impactful to the survivors’ health and well-being as more aggressive acts. It is strongly recommended to develop and use IPV instruments that measure not only the intent of acts but also various impacts of such acts [39].

Finally, IPV screening should be taken in various services/resources on campus in a uniform fashion. Students who experience IPV may seek various ways to receive help, but not necessarily from the campus resource that addresses IPV explicitly. Therefore, it is critical for other resources/services (e.g., health center, counseling services) to routinely screen IPV. This means that the professionals working at these resources/services need to be familiar with IPV screening procedures and questions; routinely asking about a client’s relationship status can provide an opportunity to discuss healthy intimate relationships, signs of IPV, and resources that can be beneficial to IPV survivors.

Competing Interests:

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

Blaydes, L., Fearon, J. D., & MacDonald, M. (2025). Understanding intimate partner violence. Annual Review of Political Science, 28, 351-374. View

World Health Organization. (2021). Violence against women prevalence estimates, 2018: Global, regional and national prevalence estimates for intimate partner violence against women and global and regional prevalence estimates for non-partner sexual violence against women. View

Daley, E. M., & Noland, V. J. (2001). Intimate partner violence in college students: A cross-cultural comparison. The International Electronic Journal of Health Education, 4, 35-40. View

Bilton, C. F., Woldford-Clevenger, C., Zapor, H., Elmquist, J., Brem, M. J., Shorey, R. C., & Stuart, G. L. (2016). Emotion dysregulation, gender, and intimate partner violence perpetration: An exploratory study in college students. Journal of Family Violence, 31(3), 371-377. View

Cho, H. (2012). Examining gender differences in the nature and context of intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27(13), 2665-2684. View

Clemens, V., Fegert, J. M., Kavemann, B., Meysen, T., Ziegenhain, U., Brähler, E., & Jud, A. (2023). Epidemiology of intimate partner violence perpetration and victimization in a representative sample. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 32, e25. View

Sánchez-Prada, A., Delgado-Álvarez, C., Bosch-Fiol, E. et al. (2023). Researching intimate partner violence against women (IPVAW): Overcoming gender blindness by improving methodology in compliance with measurement standards. Journal of Family Violence, 38, 1043–1054. View

Yakubovich, A. R., Heron, J., Metheny, N., Gesink, D., & O’Campo, P. (2021). Measuring the burden of intimate partner violence by sex and sexual identity: Results from a random sample in Toronto, Canada. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(19-20), NP18690-NP18712. View

Fanslow, J. L., Mellar, B. M., Gulliver, P. J., & McIntosh, T. K. D. (2023). Evidence of gender asymmetry in intimate partner violence experience at the population-level. Journal of interpersonal violence, 38(15-16), 9159–9188. View

An, S., Welch-Brewer, C., & Tadese, H. (2024). Scoping review of intimate partner violence prevention programs for undergraduate college students. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 25(4), 3099-3114. View

Johnson, W. L., Giordano, P. C., Manning, W. D., & Longmore, M. A. (2015). The age-IPV curve: Changes in intimate partner violence perpetration during adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Youth Adolescence, 44(3), 708-726. View

National Center for Education Statistics (2024, May). College enrollment rates. View

Coker, A. L., Follingstad, D. R., Bush, H. M., & Fisher, B. S. (2015). Are interpersonal violence rates higher among young women in college compared with those never attending college? Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 31(8), 1413-1429. View

Daly, K. A., Heyman, R. E., Smith Slep, A. M., Lorber, M. F., Cantor, D., Fisher, B. S., Lapshina, N., Chibnall, S. H., & Townsend, R. (2024). Interpersonal violence victimization among college-attending and non-college-attending emerging adults. Emerging Adulthood, 13(1), 231-238. View

Cavaletto, A., Zimmerman, L. S., Graham, L. M., & Ting, L. (2025). The state of intimate partner violence research in the community college context: A scoping review. Journal of Family Violence. View

Claydon, E. A., Ward, R. M., Davidov, D., M., DeFazio, C., Smith, K. Z., & Zullig, K. J. (2022). The relationship between sexual assault, intimate partner violence, and eating disorder symptomatology among college students. Violence and Victims, 37(1), 63-76. View

Gezinski, L. B., O’Connor, J., & Voth Schrag, R. (2025). The effect of intimate partner violence on psychological distress and suicidal ideation: An investigation of protective factors among university students in the USA. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. View

Lagdon, S., Ross, J., Waterhouse-Bradley, B., & Armour, C. (2023). Exploring the existence of distinct subclasses of intimate partner violence experience and associations with mental health. Journal of Family Violence, 38, 735–746. View

Klencakova, L. E., Pentaraki, M., & McManus, C. (2023). The impact of intimate partner violence on young women's educational well-being: A Systematic review of literature. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 24(2), 1172–1187. View

Cho, H., & Wilke, D. J. (2010). Gender differences in the nature of the intimate partner violence and effects of perpetrator arrest on revictimization. Journal Family Violence, 25(4), 393-400. View

Rennison, C. M., & Addington, L. A. (2018). Comparing violent victimization experiences of male and female college-attending emerging adults. Violence Against Women, 24(8), 952-972. View

Catalano, S. (2012). Intimate partner violence, 1993-2010. View

Smith, S. G., Chen, K. C., Basile, L. K., Gilbert, M. T., Merrick, N., Patel, M. W., & Anurag, J. (2017). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 2012 State Report. View

Fass, D. F., Benson, R. I., & Leggett, D. G. (2008). Assessing prevalence and awareness of violent behaviors in the intimate partner relationships of college students using internet sampling. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 22 (4), 66-75. View

Torres, J., Schumm, J. A., Weatherill, R. P., Taft, C. T., Cunningham, K. C., & Murphy, M. C. (2012). Attitudinal correlates of physical and psychological aggression perpetration and victimization in dating relationships. Partner Abuse, 3(1), 76-88. View

Chan, K. L., Straus, M. A., Brownridge, D. A., Tiwari, A., & Leung, W. C. (2008). Prevalence of dating partner violence and suicidal ideation among male and female university students worldwide. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health. 53(6), 529-537. View

Okuda, M., Olfson, M., Wang, S., Rubio, J. M., Xu, Y., & Blanco, C. (2015). Correlates of intimate partner violence perpetration: Results from a National Epidemiologic Survey. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(1), 49-56. View

Schwab-Reese, L. M., Peek-Asa, C., & Parker, E. (2016). Associations of financial stressors and physical intimate partner violence perpetration. Injury Epidemiology, 3:6. 1-10. View

Whitaker, D. J., Haileyesus, T., Swahn, M., & Saltzman, L. (2007). Differences in frequency of violence and reported injury between relationships with reciprocal and nonreciprocal intimate partner violence. American Journal of Public Health, 97 (5), 941-947. View

Toplu-Demirtaş, E., & Fincham, F. D. (2020). I don’t have power, and I want more: Psychological, physical, and sexual dating violence perpetration among college students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(13-14), NP11490-NP11519. View

Straus, M. A. (2011). Gender symmetry and mutuality in perpetration of clinical-level partner violence: Empirical evidence and implications for prevention and treatment. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 16(4), 279-288. View

Caldwell, J. E., Swan, S. C., & Woodbrown, D. (2012). Gender differences in intimate partner violence outcomes. Psychology of Violence, 2(1), 42-57. View

Romito, P., & Grassi, M. (2007). Does violence affect one gender more than the other? The mental health impact of violence among male and female university students. Social Science & Medicine, 65(6), 1222-1234. View

Hayes, B. E., & Kopp, P. M. (2020). Gender differences in the effect of past year victimization on self-reported physical and mental health: Finding from the 2010 National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45(2), 293-312. View

Ackerman, J. M. (2016). Over-reporting intimate partner violence in Australian survey research. British Journal of Criminology, 56(4), 646-667. View

Hamby, S. (2013). The partner victimization scale. Sewanee, TN: Life Paths Research Program. View

Hamby, S. (2016a). Advancing survey science for intimate partner violence: The partner victimization scale and other innovations. Psychology of Violence, 6(2), 352-359. View

Hamby, S. (2016b). Self-report measures that do not produce gender parity in intimate partner violence: A multi-study investigation. Psychology of Violence, 6(2), 323-335. View

Zapata-Calvente, A. L., Moya, M., & Megías, J. L. (2024). Unveiling the gender symmetry debate: Exploring consequences, instructions, and forms of violence in intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 40(17-18), 4346-4371. View

Vagi, K. J., Olsen, E. O., Basile, K. C., Vivolo-Kantor, A. M. (2015). Teen dating violence (physical and sexual) among US high school students: Findings from the 2013 National Youth Risk Behavior Survey. JAMA Pediatrics, 169(5),474-482. View

Fernández-González, L., O’Leary, K. D., & Muñoz-Rivas, M. J. (2012). We are not joking: Need for controls in reports of dating violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 28(3), 602-620. View

Holland, K. J., Cipriano, A. E., Huit, T. Z., Volk, S. A., Meyer, C. L., Waitr, E., & Wiener, E. R. (2021). “Serious enough”? A mixed-method examination of the minimization of sexual assault as a service barrier for college sexual assault survivors. Psychology of Violence, 11(3), 276–285. View

Wood, E. J., & Toppelberg, N. (2017). The persistence of sexual assault within the US military. Journal of Peace Research, 54(5), 620-633. View

Ansara, D. L., & Hindin, M. J. (2010). Formal and informal help-seeking associated with women’s and men’s experiences of intimate partner violence in Canada. Social Science & Medicine, 70(7), 1011-1018. View

Tjaden, P., & Thoennes, N. (2000). Extent, nature, and consequences of intimate partner violence: Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. View

Kimmel, M. S. (2002). Gender symmetry in domestic violence. Violence Against Women, 8(11), 1332-1363. View

Beatty, P. C. & Willis, G. B. (2007). Research synthesis: The practice of cognitive interviewing. Public Opinion Quarterly, 71(2), 287-311. View

Wani, M. A., & Mashi, A. (2015). Emotional maturity across gender and level of education. The International Journal of Indian Psychology, 2(2), 63-72. View

Neighbors, C., Palmer, R. S., & Larimer, M. E. (2004). Interest and participation in a college student alcohol intervention study as a function of typical drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 65(6), 736–740. View

Parks, K. A., Pardi, A. M., & Bradizza, C. M. (2006). Collecting data on alcohol use and alcohol-related victimization: A comparison of telephone and web-based survey methods. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 67(2), 318–323. View

Bidwell, A. (2015). Campus sexual assault: More awareness hasn’t solved root issues. View