Journal of Social Work and Welfare Policy Volume 3 (2025), Article ID: JSWWP-173

https://doi.org/10.33790/jswwp1100173Research Article

Reflexive Journeys into Social Justice: An Autoethnographic Study of Graduate Students in Social Work and Welfare

Cassandra Chaney1*, Nia Nicks1, Conial Caldwell Jr.1, Hope Allchin2, Eboni M. Chism2, Dannielle Joy Davis2, Ashleigh R. Borgmeyer1, Hailey Diestelkamp2, Sheltoria Love2, Lindsay McDaniels2, Christian Nunez2, Sydney Papadopoulos2, Rhonda Smith2, Montana Sutton2, Jennifer Tanner2, Myles Urban2, and Carlie West2

1Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, United States.

2St. Louis University, St. Louis, MO, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Cassandra Chaney, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, United States.

Received date: 19th October, 2025

Accepted date: 03rd December, 2025

Published date: 05th December, 2025

Citation: Chaney, C., Nicks, N., Caldwell, C., Allchin, H., Chism, E. M., Davis, D. J., Borgmeyer, A. R., Diestelkamp, H., Love, S., McDaniels, L., Nunez, C., Papadopoulos, S., Smith, R., Sutton, M., Tanner, J., Urban, M., & West, C., (2025). Reflexive Journeys into Social Justice: An Autoethnographic Study of Graduate Students in Social Work and Welfare. J Soci Work Welf Policy, 3(2): 173.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

This autoethnographic inquiry explored how 14 graduate students across Student Personnel Administration, Higher Education Administration, Social Work, and African American Studies conceptualize social justice within the context of their academic and professional development. Using reflexive, qualitative methods, participants provided written reflections responding to structured prompts about their definitions, experiences, and envisioned professional enactments of social justice. An inductive thematic analysis revealed five overarching themes: (1) Social Justice as Equity, emphasizing fairness and the provision of opportunities based on individual needs; (2) Social Justice as Informative, highlighting the dual responsibility of educating oneself and others about systems of oppression; (3) Social Justice as Staunch Advocacy, reflecting a commitment to defending and amplifying marginalized voices; (4) Social Justice as Consistent Bravery, representing the courage required to challenge inequitable norms and engage in difficult dialogues; and (5) Social Justice as Exterminating Oppression, capturing the pursuit of systemic change to dismantle structural inequities. Findings illustrate how participants balance critical realism regarding social injustices with optimism for transformative change, offering nuanced insight into the values, motivations, and practices of emerging professionals. Implications for social work and welfare education include fostering reflective practices, promoting inclusive pedagogy, and supporting advocacy-oriented training for graduate students.

Keywords: Social Justice; Graduate Students; Autoethnography; Reflexive Methodology; Social Work; Higher education

Introduction

“Striving for social justice is the most valuable thing to do in life”. This maxim underscores the moral urgency and enduring relevance of social justice and provides the foundation for this autoethnographic inquiry into how graduate students in Social Work and Higher Education conceptualize social justice. By exploring their narrative reflections, this inquiry seeks to understand how future professionals define and internalize this foundational concept a process that may influence their future practice and advocacy [1].

First, this work builds on continuing efforts to foreground social justice within social work and higher education. As fields that engage directly with systemic inequality, poverty, and institutional marginalization, social work and higher education programs are increasingly emphasizing social justice values in pedagogy and practice [1-5]. Second, this inquiry acknowledges the important conceptual distinction between legal justice and social justice: legal justice often centers punishment or restitution within formal systems, whereas social justice emphasizes equitable access to resources, rights, and opportunities for all [6,7].

Third, centering graduate student perspectives offers insight into how future social work and educational practitioners, who may influence institutional culture, policy, and community interventions, understand justice, equity, and structural change [1]. Finally, this study situates social justice within tangible institutional and societal inequities, including educational disparities, exclusion, and the spatial and structural barriers that marginalized students face on campus [8]. The urgency of such work is reinforced by recent evidence documenting how institutional design and campus environments continue to exclude or marginalize minority and low income students [8].

In the sections that follow, we review existing scholarship on social justice in social work ethics, higher education pedagogy, and equity-oriented practice; then outline our methodological framework and describe how this autoethnographic inquiry captures graduate students’ definitions and lived experiences of social justice.

Review of Literature

Understanding how graduate students conceptualize social justice requires grounding the inquiry within intersecting bodies of scholarship: social justice education, student development theory, critical pedagogy, and reflective writing. These literatures collectively illuminate how students learn to define, negotiate, and apply social justice in academic and professional contexts.

Social Justice Education in Graduate Programs

Social justice education aims to help learners critically analyze systems of privilege and oppression while building the skills necessary to challenge inequity [9-12]. Recent studies show that graduate students in human-services–oriented fields increasingly encounter social justice concepts as formal learning outcomes, yet they often struggle to articulate precise, systemic definitions [13]. As a result, social justice coursework must go beyond theoretical frameworks to include guided reflection, dialogue, and experiential learning that confront structural inequality directly. Without these deeper pedagogical supports, students risk engaging only at the level of individual attitudes rather than understanding and challenging institutionalized oppression.

Hytten and Bettez [14] highlight students frequently conflate social justice with interpersonal kindness or cultural appreciation unless coursework explicitly emphasizes systemic analysis). Consequently, more recently, scholars argue that examining how students formulate definitions of social justice in their own words is essential, particularly as higher education institutions face heightened political scrutiny around Diversity Equity and Inclusion (DEI) initiatives. Understanding conceptualizations at the student level can also clarify how effectively graduate programs prepare future practitioners to engage in socially just work.

Student Development Theory and Critical Consciousness

Student development scholarship offers important insight into how graduate students form social justice beliefs. Critical consciousness, originally conceptualized by Freire [15], remains a central framework for understanding how learners interpret and respond to inequity. Contemporary work emphasizes that students develop critical consciousness through intertwined processes of reflection, motivation, and action [16]. Newer studies show that graduate students often demonstrate uneven development across these dimensions, with stronger critical reflection than sustained critical action [17,18].

Identity development theories further illustrate the complex ways social identities shape how students understand justice, power, and responsibility. Marginalized students may connect social justice to lived experiences of oppression, while students with privileged identities initially gravitate toward universalist or color-evasive language [19-21]. Recent research indicates that intersectional identity exploration, particularly regarding race, gender, sexuality, and class, plays a significant role in shaping students’ social justice commitments [22]. These findings reinforce the value of examining personal narratives as a means of capturing students’ evolving understandings.

Critical Pedagogy and Learning Environments

Critical pedagogy positions classrooms as political and relational spaces where learners interrogate oppressive social structures and reimagine possibilities for liberation [15]. Graduate-level critical pedagogy research demonstrates that experiences of productive discomfort, dialogic engagement, and community-building are central to students’ development of critical consciousness [23]. More recent work shows that when instructors model reflexivity, vulnerability, and accountability, students report deeper engagement in social justice content [24,25].

However, students may also resist content that challenges deeply held beliefs, especially around racism, gender oppression, and settler colonialism [26]. Such resistance may manifest through emotional pushbacks, silence, or disengagement. Scholars emphasize that these reactions reflect critical developmental junctures rather than deficits [27]. Intentional pedagogical design, using narrative, case studies, and structured reflection, supports students in navigating these tensions.

Reflective Writing as a Tool for Critical Meaning-Making

Reflective writing is a widely used pedagogical strategy for supporting deep learning, identity development, and critical selfawareness [28,29]. In social justice-focused courses, reflective writing encourages students to integrate personal experiences with academic frameworks, thus promoting transformative learning [30,31]. Recent empirical work affirms that reflective writing helps students articulate nuanced understandings of privilege, oppression, and professional responsibility [32].

Studies published in the last two years highlight that structured reflective prompts, particularly those focused on positionality and lived experience, enable students to recognize how their identities shape meaning making [24,33]. Reflective writing also surfaces emotional responses to social justice learning, which scholars argue is essential for long-term commitment to equity-oriented practice [34].

Narrative-based reflection allows students to re-story key experiences that influenced their understanding of justice, offering rich qualitative data for exploring conceptual development [35,36]. Thus, reflective writing is both a pedagogical tool and a methodological resource for studying students’ conceptualizations of social justice.

Synthesis of Literature and Research Questions

Scholarly insights converge in three important ways. First, students’ social justice definitions vary significantly and are shaped by identity, prior experience, and disciplinary context. Second, critical pedagogy and reflective writing serve as mechanisms for developing critical consciousness and deepening students’ understanding of systemic injustice. Finally, there remains a need for empirical work capturing students’ firsthand conceptualizations across diverse graduate programs, particularly amid current political challenges to equityfocused education. This study addresses these gaps by analyzing reflective writing from graduate students in multiple human-services fields to understand how they define social justice and the experiences that shape those definitions. Taken together, the existing scholarship underscores the importance of examining how students develop and articulate their understanding of social justice within reflective and pedagogically intentional learning environments. Despite growing research on critical pedagogy and student development, few empirical studies capture students’ own words as they define social justice and connect those definitions to lived experience, disciplinary training, and future professional roles. This gap highlights the need for qualitative inquiry that centers student narratives to illuminate the meanings they ascribe to social justice and the formative experiences that shape those meanings. Guided by this literature, the present study is driven by the following research questions:

Research Questions

1. How do graduate students across human-services–oriented disciplines conceptualize social justice in their reflective writing?

2. What personal, academic, or professional experiences do students identify as shaping their understanding of social justice?

3. In what ways do students envision acting in support of social justice within their future professional roles?

Methodology

This study employed a qualitative, autoethnographic, and reflexive approach to explore graduate students’ conceptualizations of social justice. Autoethnography enabled the researchers to examine cultural phenomena through both personal and participant narratives while reflecting on their own positionality, experiences, and biases [37]. Reflexive methodology ensured that the authors critically considered their dual roles as instructors and researchers, acknowledging how these roles may have influenced participants’ responses and the interpretation of the data. Because this study used an autoethnographic approach, where the researchers’ reflections and participants’ written narratives were integrated into the analysis as part of a broader cultural exploration, formal Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was deemed not necessary; however, all ethical standards regarding voluntary participation, consent, and confidentiality were strictly followed.

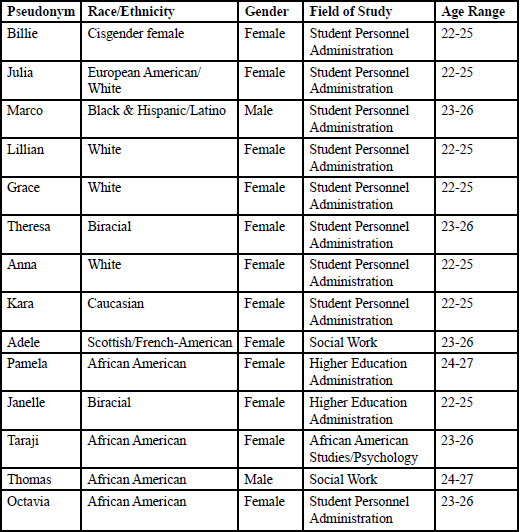

Sample. Fourteen graduate students participated in the study. Eight students (57%) were enrolled at a university in the Midwest, and six (43%) were enrolled at a university in the South. Nine students (64%) were in Student Personnel Administration, two (14%) were in Higher Education Administration, two (14%) were in Social Work, and one student (8%) was dually enrolled in African American Studies and Psychology.

In terms of racial identity, seven students (50%) identified as White, four (29%) identified as Black, two (14%) identified as African American and White, and one (7%) identified as European American and White. Regarding gender identity, eleven students (79%) identified as female, two (14%) identified as male, and one student (7%) identified as a cisgender female.

Most students (n = 13, 93%) were born in the United States, and one student (7%) was born in Germany. U.S. birthplaces included Missouri (n = 5), Florida (n = 1), Illinois (n = 1), Iowa (n = 1), Kentucky (n = 1), Louisiana (n = 1), New Jersey (n = 1), New York (n = 1), and Tennessee (n = 1).

Demographic information, including race/ethnicity, gender, and field of study, was collected to contextualize findings [See Table 1 – Participant Demographics].

Procedure. Graduate students were invited to participate voluntarily after completing a reflective writing assignment on social justice in the context of their field. Participation was entirely optional, and students were assured that declining or withdrawing would not affect course performance. The students participated in the 21st Annual 2021 Sam and Marilyn Fox ATLAS Week Conference titled, “THE HOUSE THAT RACE BUILT” which was held April 12-16, 2021. According to St. Louis University’s (SLU) website, “The Atlas Week Signature Symposium is presented by internationally renowned speakers who have dedicated their lives to issues of political and social justice [38].” Considering the ongoing Coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic, the ATLAS Week Conference was held virtually via Zoom.

Since political and social justice were the foundation of the conference, the SLU professor and LSU professor worked together to cultivate a research collaboration between their two classes: Social Justice and the College Student (SLU) and Research Practicum (LSU). The research question for this collaboration was: What are postsecondary students’ perspectives of social justice? Students from both institutions were encouraged to explore this major question using journaling, specifically answering the following guided questions:

1. How do you define social justice?

2. What personal experiences have shaped your perspectives on social justice?

Overall findings of these journal entries served as the foci of the collaborative professional presentation to the virtual community entitled “What Does Social Justice Mean to You? A Collective Autoethnography.” The presentation was well received by the virtual audience, who also shared their perspectives on social justice.

Data were collected from written reflections submitted as part of regular coursework. Participants responded to structured prompts designed to elicit personal definitions and experiences related to social justice, including questions such as, “What does social justice mean to you?” “Describe a moment or experience that shaped your understanding of social justice,” and “How do you see yourself acting in support of social justice in your professional role?” Reflections ranged from 300 to 800 words and were collected once during the semester. All reflections were de-identified before analysis, and participants provided consent for their reflections to be used in research and publication.

Analysis. The data were analyzed manually using an inductive coding strategy consistent with qualitative thematic analysis [39]. The analytic process involved open coding to identify meaningful segments of text, axial coding to group similar codes into categories forming preliminary themes, and selective coding to refine these categories into the five overarching themes presented in the findings. To enhance trustworthiness, the authors employed several strategies, including reflexive memoing to document reflections on researcher positionality, consensus coding in which the first and fifth authors independently coded the data and resolved discrepancies through discussion, maintaining an audit trail of coding decisions and theme development, and member checking, whereby participants reviewed theme summaries to provide feedback on accuracy and credibility. This rigorous and transparent approach ensured that findings were grounded in participants’ experiences while acknowledging the influence of researcher reflexivity.

Ethical Considerations. Ethical considerations were central to this study given the use of graduate students’ reflective writing as data. As this study employed an autoethnographic and reflexive qualitative approach, the primary data source consisted of deidentified reflections submitted as part of coursework. Because the study focused on reflections authored by the instructors themselves and their students in a classroom context, formal IRB approval was not deemed necessary; the research was conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines for reflective autoethnographic inquiry and pedagogical research [37,40,41].

Students were invited to participate voluntarily, and written consent was obtained for the use of their reflections in research and publication. Participation was entirely optional, and students were explicitly informed that declining participation would have no effect on course grades or evaluation. All reflections were de-identified prior to analysis to protect participant privacy, and pseudonyms were used in reporting findings. These procedures align with established ethical standards for qualitative research, including considerations of confidentiality, informed consent, and the protection of vulnerable participants [42-44]. Notably, all students expressed genuine interest in the project and eagerly chose to participate, viewing it as a valuable opportunity to present their insights at the conference and contribute their autoethnographic perspectives to published scholarly work. Their enthusiasm further affirmed the collaborative and empowering nature of the research process.

By situating this work within an autoethnographic framework and maintaining strict confidentiality protocols, the study adhered to ethical best practices while allowing participants to share their perspectives openly. Reflexivity was maintained throughout the research process, with the authors critically examining their dual roles as instructors and researchers and acknowledging how positionality may have influenced both student responses and the interpretation of the data [45]. The researchers also recognized that their social identities, disciplinary training, and professional commitments shaped the questions they asked and the meanings they drew from participant narratives. Ongoing reflexive memoing and peer debriefing further supported transparency by helping the authors identify and bracket potential biases while remaining attentive to the power dynamics inherent in instructor–student relationships.

Positionality of the Instructors/Researchers

As instructors and researchers, we recognize that our social identities, professional roles, and scholarly commitments shape every stage of the research process, from the questions we asked to the ways we interpreted students’ reflections. Our positionality within higher education, coupled with our ongoing engagement in equityfocused pedagogy, influenced how we facilitated classroom dialogue and structured the autoethnographic prompts. We acknowledge that holding positions of authority in the classroom creates inherent power dynamics, and we worked intentionally to mitigate these dynamics by emphasizing voluntary participation, confidentiality, and student agency in both the conference presentation and the written components of the study. Moreover, our own commitments to social justice and critical reflexivity informed the interpretive lens through which we understood students’ narratives. By naming these positional influences, we aim to enhance transparency, strengthen trustworthiness, and model the reflexive practice we ask of our students.

Presentation of the Findings

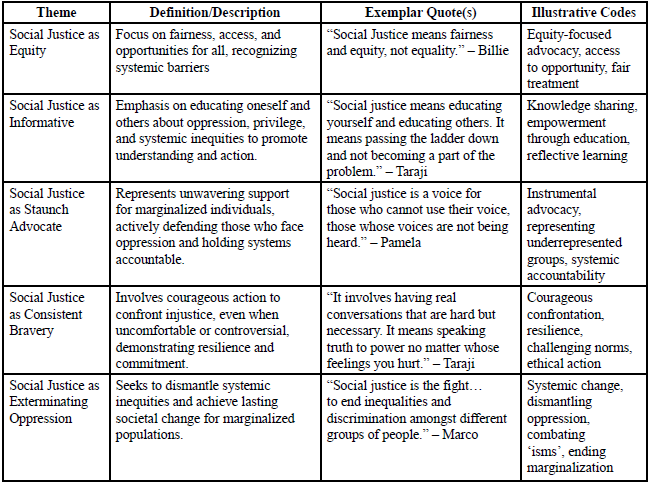

Qualitative analysis of 14 graduate student reflections revealed five overarching themes regarding conceptualizations of social justice: (1) Social Justice as Equity, (2) Social Justice as Informative, (3) Social Justice as Staunch Advocate, (4) Social Justice as Consistent Bravery, and (5) Social Justice as Exterminating Oppression. These themes represent the ways students balance recognition of systemic inequities with optimism about creating a more equitable society. Table 2 summarizes these themes, definitions, exemplary quotes, and illustrative codes.

Social Justice as Equity

Students emphasized the distinction between equality and equity, highlighting the importance of tailored support to ensure that historically marginalized individuals have meaningful access to opportunities [46]. For example, one participant explained, “Social Justice means fairness and equity, not equality” (Billie). Participants recognized that oppressive systems create structural barriers that prevent equal outcomes, and that social justice work requires actively addressing these inequities. They also noted that achieving equity is an ongoing process that demands vigilance, reflection, and adaptation of practices to meet the evolving needs of communities. Moreover, students highlighted the role of advocacy and allyship in dismantling systemic inequalities, emphasizing that individual action must be coupled with structural change.

Social Justice as Informative

Several students described social justice as a commitment to learning about oppression and educating others. This aligns with critical pedagogy and student development theory, which suggest that knowledge of systemic inequities empowers individuals to act ethically by challenging injustice [47-49]. One participant stated, “Social justice means making good trouble by speaking truth to power. It means educating yourself and educating others” (Taraji). Reflections indicated that students viewed education as both a personal responsibility and a mechanism for societal change. Students also emphasized that ongoing self-reflection and critical dialogue are essential to deepening understanding of inequities. Furthermore, they noted that sharing knowledge with peers and community members amplifies the impact of social justice work beyond individual actions.

Social Justice as Staunch Advocate

Participants articulated that social justice entails advocacy for those without a voice, including practical, instrumental, and educational support [50]. For instance, one student described social justice as “a voice for those who cannot use their voice, those whose voices are not being heard” (Pamela). Students highlighted the importance of challenging inequitable policies and systems while supporting the empowerment of marginalized populations, reflecting historical precedents in social work and civil rights advocacy [51,52]. They emphasized that advocacy requires both action and sustained commitment to systemic change. Additionally, participants noted that social justice work involves building coalitions and fostering collaboration to amplify marginalized voices and create meaningful impact.

Social Justice as Consistent Bravery

Graduate students recognized that enacting social justice often requires courage to confront inequities and engage in difficult conversations. As one participant noted, “It means speaking truth to power no matter whose feelings you hurt because you know that hurt feelings are the first steps of true, meaningful change happening” (Taraji). This theme illustrates how students link social justice to moral courage and ethical responsibility, emphasizing that discomfort is inherent to progress [53-55]. Participants further acknowledged that taking courageous action can inspire others to engage in social justice work, creating a ripple effect across communities. They also stressed that moral courage is not a one-time act but an ongoing commitment to challenging injustice in daily interactions and institutional practices.

Social Justice as Exterminating Oppression

Finally, students described social justice as actively dismantling systemic oppression and addressing societal hierarchies. One participant explained, “Social justice is the fight, the battle, the idea that will continue to end inequalities and discrimination amongst different groups of people” (Marco). This theme underscores a proactive, systemic view of justice, connecting personal action to structural change and reflecting the necessity of both awareness and intervention in social justice work [56].

Overall, these findings demonstrate that graduate students conceptualize social justice in multifaceted ways that combine awareness of inequities with proactive strategies for education, advocacy, courage, and systemic transformation. The frequency and consistency of these themes across participants suggest a shared understanding shaped by both disciplinary training and personal experience, highlighting areas for curriculum development in social justice education.

Analytic Interpretation

Social Justice as Equity was endorsed by 11 of the 14 participants, reflecting the centrality of fairness and equitable treatment in their conceptualizations. Students differentiated equity from equality, noting that social justice requires addressing structural barriers to provide individuals with the support necessary to succeed. This aligns with prior research emphasizing the importance of equityfocused approaches in higher education and social work [46,57].

Social Justice as Informative emerged in responses from 9 participants, emphasizing education as a mechanism for empowerment and systemic change. Participants highlighted the dual responsibility of learning about oppression themselves and helping others understand inequities, reflecting critical pedagogy principles and student development literature regarding moral and ethical growth [48].

Social Justice as Staunch Advocate appeared in 10 participants’ reflections. Students framed advocacy both in practical terms (e.g., promoting access to resources) and symbolic terms (giving voice to marginalized populations), consistent with social work and higher education scholarship on advocacy as a core professional competency [50,51].

Social Justice as Consistent Bravery was articulated by 8 participants, highlighting the courage required to confront entrenched inequities, challenge peers, and navigate uncomfortable conversations. This theme reflects findings from leadership and social justice education research emphasizing moral courage as critical for effective advocacy [34].

Social Justice as Exterminating Oppression was articulated by 7 participants, who emphasized the ultimate goal of social justice: systemic transformation and dismantling inequities perpetuated by “isms” such as racism, sexism, and ableism. This perspective underscores the importance of both individual action and structural engagement, aligning with frameworks of anti-oppressive practice [58].

Overall, while participants’ disciplinary backgrounds varied (Student Personnel Administration, Higher Education Administration, Social Work, and African American Studies), the prevalence of themes demonstrates shared understandings of social justice as both an ethical commitment and an actionable practice. Patterns in responses suggest that most students integrate knowledge acquisition, advocacy, and courage into a holistic conception of social justice, reflecting both theoretical and applied dimensions.

Discussion

This study employed an inductive thematic analysis to examine how 14 graduate students across Social Work, Higher Education, Student Personnel Administration, and African American Studies conceptualize social justice. Five primary themes emerged: (1) Social Justice as Equity, (2) Social Justice as Informative, (3) Social Justice as Staunch Advocate, (4) Social Justice as Consistent Bravery, and (5) Social Justice as Exterminating Oppression. Despite disciplinary differences, participants demonstrated a balance between recognizing systemic challenges and maintaining optimism about achieving a more equitable society, reflecting prior research on graduate students’ social justice perspectives [59].

Social Justice as Equity

Participants distinguished between equality and equity, emphasizing that fairness requires accommodating structural disadvantages rather than providing identical resources to all [57,60]. Equity-centered perspectives align with contemporary scholarship on social justice in higher education and social work, which underscores the importance of addressing historical and systemic inequities [8,61]. Students noted that equity involves tailoring support to meet individuals’ unique needs, particularly for those who have been marginalized by longstanding institutional barriers. Several participants stressed that equity-focused practices must be proactive rather than reactive, requiring intentional design rather than after-the-fact adjustments. Others emphasized that achieving equity depends on continually reassessing policies, resources, and assumptions to ensure that institutional practices evolve alongside shifting social and cultural conditions.

Social Justice as Informative

Participants highlighted the transformative power of education, both personal and communal, as a tool for disrupting ignorance and fostering awareness of systemic oppression [6,62]. Consistent with John Lewis’s advocacy of “good trouble,” students emphasized the dual responsibility to educate themselves and others to catalyze meaningful change. Several participants described education as an ongoing process that requires humility, openness, and a willingness to confront uncomfortable truths. They also noted that sharing knowledge within their communities can serve as a catalyst for collective empowerment and action. In addition, students recognized that educational spaces—formal and informal can become sites of resistance, where dominant narratives are challenged and reimagined through critical dialogue.

Social Justice as Staunch Advocate

Advocacy emerged as a central component of participants’ conceptualizations, encompassing practical, educational, and instrumental strategies for supporting marginalized populations [51,52,63]. This aligns with historical and contemporary understandings of social work and higher education professionals as mediators between individuals and oppressive systems [1,64]. Students emphasized that advocacy requires both individual initiative and collective action, particularly when confronting systemic barriers. Several participants described advocacy as a sustained practice that extends beyond single events, involving continuous engagement with policy, institutional culture, and community needs. Others noted that effective advocacy is relational, relying on trust-building, collaboration, and an awareness of the lived experiences of those most affected by inequity.

Social Justice as Consistent Bravery

Participants identified courage as essential to social justice work, particularly when confronting entrenched systems of oppression or engaging in difficult conversations about identity and inequity [26,56]. Social justice requires sustained engagement even when it challenges dominant norms or causes interpersonal conflict. Students emphasized that courage involves not only speaking up but also being willing to listen, learn, and unlearn long-held assumptions. Several participants noted that taking courageous action often means accepting discomfort as a necessary part of growth and accountability. Others described courage as a collective practice, strengthened through supportive relationships and communities that share a commitment to equity and justice. Participants further explained that courage is cultivated over time as individuals become more confident in naming injustice and advocating for change. Many also highlighted that courageous action often begins with small steps, such as asking critical questions or challenging harmful comments in everyday interactions. Finally, students acknowledged that courage can be situational, requiring them to discern when to intervene directly and when to leverage support from peers or mentors.

Social Justice as Exterminating Oppression

Finally, participants framed social justice as actively dismantling oppressive systems that generate disparities in wealth, health, education, and safety [56,65-67,69]. They emphasized selfreflexivity, recognizing the need for individuals who benefit from systemic privilege to interrogate their own roles in perpetuating inequities [6,70]. Participants also highlighted the importance of translating social justice principles into concrete actions within their professional and personal spheres. Many noted that fostering systemic change requires sustained collaboration with communities and institutions to challenge entrenched power structures. Students described social justice work as iterative, necessitating continual learning, reflection, and adaptation to emerging social issues. Several emphasized the interconnectedness of social justice domains, noting that advocacy, equity, and education mutually reinforce one another. Finally, participants recognized the emotional labor involved in this work, underscoring the need for resilience, support networks, and self-care to sustain long-term engagement.

Collectively, these findings demonstrate that graduate students’ conceptualizations of social justice encompass both aspirational ideals and actionable strategies, reflecting a depth-oriented understanding of equity, education, advocacy, courage, and systemic change. Future work should explore these perspectives longitudinally and across diverse national contexts to better understand how social justice ideologies evolve over time [8]. Additionally, research could examine how students’ personal identities and lived experiences influence their approaches to social justice, particularly in navigating power dynamics within institutional settings. Investigating the role of mentorship and peer support may also shed light on factors that strengthen commitment to equity-oriented action. Finally, exploring how these conceptualizations translate into professional practice could provide insights for curriculum development and training programs aimed at preparing socially conscious leaders.

Limitations

Despite the valuable insights generated through this autoethnographic inquiry, several limitations warrant careful consideration. First, the relatively small sample of 14 graduate students limits the extent to which findings can be generalized to broader populations. Qualitative research with small, purposefully selected samples often provides rich, contextualized understanding, but generalizability remains inherently constrained [41]. Second, because participants were drawn from only two institutions and fields primarily within the social sciences, institutional context and disciplinary homogeneity may have shaped the patterns observed; the perspectives of students in other disciplines (e.g., humanities, STEM, professional programs) or at other institutions remain unexplored. Third, the cross sectional nature of the inquiry, relying on a single reflective writing assignment per participant, captures only a snapshot in time rather than potential evolution or change in conceptualizations of social justice. As recent longitudinal qualitative scholarship shows, temporal dynamics significantly influence how justice oriented identities and experiences develop across time [55]. Fourth, qualitative analysis depends on interpretive judgment and reflexivity; despite efforts to promote consensus coding and reflexive memoing, researcher subjectivity and context-specific meaning could introduce bias or limit transferability across populations [71]. Finally, the reliance on written reflections, rather than interviews or follow-up dialogues, may have constrained the depth or richness of data; participants’ responses were subject to their comfort, writing ability, and willingness to disclose, which may have affected the breadth and subtlety of expressed perspectives. Overall, while the study offers meaningful, in-depth insight into graduate student conceptualizations of social justice, these limitations suggest caution in generalizing the findings broadly and point to the need for further research with larger, more diverse, and longitudinal designs.

Directions for Future Research

Future work can build on this autoethnographic inquiry in several important ways. First, researchers should recruit a larger and more diverse sample of graduate students, within the United States and internationally (e.g., Canada, the United Kingdom, and other regions), to explore whether and how conceptualizations of social justice vary across cultural, institutional, and sociopolitical contexts. Second, similar inquiries should extend beyond social science disciplines, incorporating students in the humanities, STEM, and professional fields to assess whether disciplinary background shapes social justice meaning making. Third, longitudinal designs would offer valuable insight into how students’ definitions of social justice evolve over time, especially in response to life events, professional development, and exposure to systemic inequities [72].

Fourth, comparative cross national research could illuminate the influence of national policies, cultural norms, and welfare regimes on graduate students’ experiences and definitions of social justice. Finally, future studies should investigate specific personal, academic, and professional experiences that inform how students define and practice social justice, thereby identifying the critical events or interactions that give rise to justice oriented identity and action. Such expanded efforts will deepen the empirical foundation for social work and welfare education, informing curriculum design, training, and advocacy-focused practice, and align with recent scholarship that demonstrates the value of autoethnographic and reflexive methods for social-justice pedagogy [1,24], as well as the call for crossdisciplinary, inclusive, and comparative inquiry in social justice education.

Conclusion

In this autoethnographic inquiry, graduate students across multiple human-services disciplines demonstrated rich, nuanced conceptualizations of social justice, reflecting both personal and professional experiences. The five identified themes Equity, Informative, Staunch Advocacy, Consistent Bravery, and Exterminating Oppression highlight the multifaceted ways in which graduate students understand and enact social justice. Participants balanced critical awareness of systemic inequities with optimism and commitment to effect meaningful change. Their reflections underscore the importance of fostering self-reflexivity, ethical awareness, and advocacy skills in graduate education. By centering student narratives, this study provides insight into the values, motivations, and strategies emerging professionals bring to socially-just practice. These findings have practical implications for social work and welfare education, particularly in designing curricula that emphasize reflective practice, critical pedagogy, and inclusive engagement. While the sample was small, the depth and richness of the narratives align with qualitative, autoethnographic methods, offering insight not achievable through large-scale surveys. Ultimately, this work affirms that cultivating socially conscious professionals requires intentional attention to both personal growth and structural change.

Competing Interests:

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

Maclatchy, A., Nguyen, L., Olulanke, O., Pownall, L., & Usman, M. (2025). Towards an education through and for social justice: Humanizing a life sciences curriculum through co-creation, critical thinking and anti-racist pedagogy. Social Sciences, 14(3). View

Bentley, K. J., Mancini, M., Jacob, A., & McLeod, D. A. (2019). Teaching Social Work Research through the lens of social justice, human rights, and diversity. Journal of Social Work Education, 55(3), 433–448. View

Cho, H. (2017). Navigating the meanings of social justice, teaching for social justice, and multicultural education. International Journal of Multicultural Education, 19(2), 1–19. View

Reisch, M., & Garvin, C. D. (2016). Social work and social justice: Concepts, challenges, and strategies. Oxford University Press. View

Scheve, M., & Piper, M. (2025). Working for social justice: A review of students as leaders in pedagogical partner programs. Social Sciences, 14(3), 155-168. View

Dauria, E., Folk, J., Godoy, S., Holloway, E., McPhee, J., Hoskins, D., ... & Tolou-Shams, M. (2025). Advancing antiracist research: Addressing health inequities among juvenile legal system-impacted youth using public health critical race praxis. Health & Justice, 13(1), 45. View

Mejía, E. F., Aguilar Bobadilla, M. d. R., & Slater, C. (2024). Leadership for social justice: A study of directors of the National Pedagogical University of Mexico City. Journal of Educational Leadership, Policy and Practice, 38(1), 46–67. View

Bart-Plange, D. J., Henderson, K., Hoffman, K., & Trawalter, S. (2025). Critiquing and reimagining belonging in public spaces in higher education. Educational Psychology Review, 37, Article 87. View

Barry, B. (2005). Why social justice matters. Polity. View

Benner, K., Loeffler, D., & Buchanan, S. (2019). Understanding Social Justice Engagement in Social Work Curriculum. Journal of Baccalaureate Social Work, 24(1), 321–337. View

Finn, J. L. (2020). Just practice: A social justice approach to social work. Oxford University Press. View

Hodgson, D., & Watts, L. (2025). Social justice in social work research. In Handbook of Research Methods in Social Work (pp. 130-143). Edward Elgar Publishing. View

McArthur, J. (2018). Assessment for social justice: Perspectives and practices within higher education. Bloomsbury Publishing. View

Hytten, K., & Bettez, S. C. (2011). Understanding education for social justice. In M. W. Apple, W. Au, & L. A. Beane (Eds.), The Routledge international handbook of critical education (pp. 45–60). Routledge. View

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Herder and Herder. View

Thomas, D. R. (2006). A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Evaluation, 27(2), 237–246. View

Camargo, E., Ramos, D., Bennett, C. B., Talley, D. Z., & Silva, R. G., Jr. (2025). Disrupting dehumanizing norms of the academy: A model for conducting research in a collective space. Innovative Higher Education, 50(1), 107–134. View

Gutiérrez, I. V., & Ko Wong, L. (2024). (Re)structuring and (re)imagining the first year experience for graduate students of color using community cultural wealth. Education Sciences, 14(6), 552. View

Pérez, D., II, & Reyes, K. B. (2023). Identity, power, and student meaning-making in social justice learning environments. Equity & Excellence in Education, 56(4), 482–499.

Ryan, T. G., & Deci, T. S. (2024). Challenging colorevasiveness in higher education: Student identity, privilege, and the development of critical racial literacy. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 17(2), 145–160.

Sue, D. W. (2010). Microaggressions in everyday life: Race, gender, and sexual orientation. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. View

Albizu, P. J. (2024). Toward an intersectional leadership identity development approach. Education Sciences, 14(12), 1274. View

Geng, F., & Yu, S. (2024). Exploring doctoral students’ emotions in feedback on academic writing: a critical incident perspective. Studies in Continuing Education, 46(1), 1-19. View

Rosen, S. M., Jacobs, C. E., Whitelaw, J., Mallikaarjun, V. R., & Rust, F. (2024). Justice centered reflective practice in teacher education: Pedagogy as a process of imaginative and hopeful invention. Education Sciences, 14(4), 376-394. View

Pérez Beverly, S. (2025). Enacting inclusive practices in STEM environments by engaging STEM faculty in self reflexivity. Frontiers in Education, 10, Article 1630132. View

Feagin, J. (2013). Systemic racism: A theory of oppression. Routledge. View

Campbell, E. T., Gu, S. Y., Guy, K. H., Hackney, A. J., Jones, A. M., Kearley, A. N., Kennedy, C., Neely Cowan, A., Pitzel, A., Quito, D., Rich, E. E., Shelton, S. A., Salter Virgin, A., & Watson, V. T. (2025). Refusals and reflections: Teaching and learning social justice in qualitative research. Brill.

Boud, D., Keogh, R. and Walker, D. (2013) Reflection: Turning Experience into Learning. Routledge. View

Reamer, F. G. (2021). Reflective equilibrium in social work ethics: An essential concept. Journal of Social Work Values & Ethics, 18(1), 105–114. View

Nicotera, A. (2019). Social Justice and Social Work, a Fierce Urgency: Recommendations for Social Work Social Justice Pedagogy. Journal of Social Work Education, 55(3), 460–475. View

Schroeder, J., & Pogue, R. (2011). An investigation of transformative education theory as a basis for social justice education in a research course. In J. Birkenmaier, A. Cruse, E. Burkemper, J. Curley, R. J. Wilson, & J. J. Stretch (Eds.), Educating for social justice: Transformative experiential learning (pp. 111–126). Lyceum Press. View

Bright, D., McKay, A., & Firth, K. (2024). How to be reflexive: Foucault, ethics and writing qualitative research as a technology of the self. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 47(4), 408-420. View

Smith, N., Erwin, K., Taliaferro, A., & Petty, C. (2024). Journaling as a reflective tool in a rural teacher residency experience. Theory & Practice in Rural Education, 14(2), 107– 122. View

Reynolds, M., & Vince, R. (2017). Organizing reflection: An introduction. In Organizing Reflection (pp. 1-14). Taylor and Francis. View

Mulvale, J. P. (2021). Six aspects of justice as a grounding for analysis and practice in social work. Journal of Social Work Values & Ethics, 18(1), 34–48. View

Tolliver, D. E., & Tisdell, E. J., (2006). Engaging spirituality in the transformative higher education classroom. 37-47. View

Ellis, C., Adams, T. E., & Bochner, A. P. (2011). Autoethnography: An overview. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 12(1), Article 10. View

St. Louis University. (2021, April 16). The 21st annual Sam and Marilyn Fox Atlas Week signature symposium. View

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. View

Muncey, T. (2010). Creating autoethnographies. SAGE Publications. View

Taylor, S. J., & Bogdan, R. (1998). Introduction to qualitative research methods: A guidebook and resource (3rd ed). New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. View

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). SAGE Publications. View

Orb, A., Eisenhauer, L., & Wynaden, D. (2001). Ethics in qualitative research. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 33(1), 93–96. View

Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative Quality: Eight “Big-Tent” Criteria for Excellent Qualitative Research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16, 837-851. View

Finlay, L. (2002). “Outing” the researcher: The provenance, process, and practice of reflexivity. Qualitative Health Research, 12(4), 531–545. View

Brown, R. D. (2017). EIGHT. Equal Rights, Privilege, and the Pursuit of Inequality. In Self-Evident Truths (pp. 297-310). Yale University Press. View

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Seabury Press. View

Kuh, G. D., Cruce, T. M., Shoup, R., Kinzie, J., & Gonyea, R. M. (2008). Unmasking the effects of student engagement on first-year college grades and persistence. The Journal of Higher Education, 79(5), 540–563. View

National Association of Social Workers (n.d.) Code of Ethics. View

McLaughlin, A. M. (2009). Clinical social workers: Advocates for social justice. Advances in Social Work, 10(1), 51-68. View

Gal, J. (2001). The perils of compensation in social welfare policy. Social Service Review, 75(2), 225–244. View

Titmuss, R. (1968). Commitment to welfare. George Allen & Unwin. View

Jankowski, P. J., Sandage, S. J., Wang, D. C., Zyphur, M. J., Crabtree, S. A., & Choe, E. J. (2024). Longitudinal processes among humility, social justice activism, transcendence, and well being. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, Article 1332640. View

Mayes, E., & Arya, D. (2024). Just participatory research with young people involved in climate justice activism. Journal of Applied Youth Studies, 7, 385–395. View

Wood, C. V., Salusky, I., Jones, R. F., Remich, R., Caliendo, A. E., & McGee, R. (2023). Using longitudinal qualitative research to understand the experiences of minoritized people. Methods in Psychology, 10, 100130. View

Pope, R. L., Reynolds, A. L., & Mueller, J. A. (2019). "A Change Is Gonna Come": Paradigm shifts to dismantle oppressive structures. Journal of College Student Development, 60(6), 659- 673. View

Blacksher, E., & Valles, S. A. (2021). White privilege, white poverty: Reckoning with class and race in America. Hastings Center Report, 51, S51-S57. View

Low, J., Wyke, B., & Barley-McMullen, S. (2025). Antioppressive practice. In A Student's Guide to Placements in Health and Social Care Settings (pp. 47-63). Routledge. View

Bhuyan, R., Bejan, R., & Jeyapal, D. (2017). Social workers’ perspectives on social justice in social work education: When mainstreaming social justice masks structural inequalities. Social Work Education, 36(4), 373-390. View

Dailey, S. J. (2021). The Black Community’s Quest for Equality: Resolving Poverty in the Black Community-Embracing Diversity. Dorrance Publishing. View

Kao, A. C. (2020). Health of we the people. AMA Journal of Ethics, 22(9), 753-756. View

King, J. (July 1, 2020). How racist is Britain today? What the evidence tells us. View

McLaughlin, A. M. (2009). Clinical social workers: Advocates for social justice. Advances in Social Work, 10(1), 51-68. View

Lopez-Baez, S. I., & Paylo, M. J. (2009). Social justice advocacy: Community collaboration and systems advocacy. Journal of Counseling & Development, 87(3), 276-283. View

Baines, D. (2007). Anti-oppressive social work practice. Doing anti-oppressive practice: Building transformative politicized social work, 1-30. View

Chaney, C., & Robertson, R. (2013). Racism and police brutality in America. Journal of African American Studies, 17(4), 480- 505. View

Chaney, C., & Robertson, R. (2014). “Can We All Get Along?” Blacks’ Historical andContemporary (In)Justice with Law Enforcement. Western Journal of Black Studies, 38(2), 108-122. View

Chaney, C., & Robertson, R. (2015). Armed and dangerous? An examination of fatal shootings of unarmed Black people by police. Journal of Pan African Studies, 8(4), 45-78. View

Robertson, R., V. & Chaney, C. D. (2019). Police use of excessive force against African Americans: Historical antecedents and community perceptions. Rowman & Littlefield. View

Brown, C. S. (2002). Refusing racism: White allies and the struggle for civil rights. Teachers College Press. View

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research techniques. Sage. View

Reisch, M. (2002). Defining social justice in socially a socially unjust world. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Human Services, 83(4), 343–354. View