Journal of Social Work and Welfare Policy Volume 3 (2025), Article ID: JSWWP-174

https://doi.org/10.33790/jswwp1100174Research Article

Operation Resilience: A Community-Based Peer Support Program to Enhance Well-Being and Suicide Prevention Among Combat Veterans

Keita Franklin1*, Meaghan LeMay2 and Clark Pennington3

1Co Director, Columbia Lighthouse, Columbia Psychiatry, Stafford, Virginia, United States.

2Behavioral Health Specialist Leader, United States.

3Law Enforcement Executive and Behavioral Health Program Strategist, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Keita Franklin, Co Director, Columbia Lighthouse, Columbia Psychiatry, Stafford, Virginia, United States.

Received date: 27th September, 2025

Accepted date: 05th December, 2025

Published date: 08th December, 2025

Citation: Franklin, K., LeMay, M., & Pennington, C., (2025). Operation Resilience: A Community-Based Peer Support Program to Enhance Well-Being and Suicide Prevention Among Combat Veterans. J Soci Work Welf Policy, 3(2): 174.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Veteran suicide remains a serious public health concern in the United States, with rates significantly higher than in the civilian population. Traditional healthcare systems alone cannot reach all at-risk veterans, highlighting the importance of community-based interventions. Operation Resilience is a community-based, peerdriven program that integrates a biopsychosocial-spiritual approach to support veterans exposed to combat trauma. This paper describes the design, implementation, and evaluation of Operation Resilience. Data from pre- and post-intervention surveys and a follow-up focus group point toward improvements in social support, resilience, and connection to community resources among participants. Qualitative feedback underscores the value of peer connection, practical coping skills, and sustained support networks. Among the 84 participating veterans, perceived peer support increased significantly from pre- to post-intervention. These findings support the potential for Operation Resilience to serve as a complementary public health approach to veteran suicide prevention outside traditional clinical settings.

Keywords: Veterans, Suicide Prevention, Peer Support, Community- Based Intervention, Resilience

Introduction

Veteran suicide remains a serious public health concern in the United States. Over 78,000 U.S. veterans died by suicide between 2005 and 2017, and the suicide rate among veterans is approximately 1.5 times higher than that of non-veteran adults when adjusted for age and sex [1]. In 2022 there were an average 17.6 Veteran suicides per day, of which 7.0 per day were among Veterans who received Veteran Health Administration (VHA) care in 2021 or 2022 and 10.5 were among other Veterans [2]. In 2022 alone, 6,407 veterans died by suicide, reflecting the disproportionate burden of suicide in this population. Of these tragic losses, 73.5% of Veteran suicide involve firearms a marked disparity between non Veterans and a reflection of cultural and environmental factors. This elevated risk has been attributed to both the related trauma and broader social factors such as adjustment difficulties and isolation, underscoring the urgency of developing effective prevention strategies for veterans.

Traditional healthcare-based approaches, while critical, may be insufficient on their own to reach all veterans in need. Fewer than half of U.S. veterans are enrolled in Veterans Affairs (VA) health services, and many at-risk individuals have limited recent contact with medical providers [1]. Only about 45% of people who die by suicide have seen a primary care provider in the month before their death [3]. Further, this is consistent amongst the Veteran community who frequently engage with primary care teams in the days or months prior to their deaths [4]. This suggests that clinically based interventions alone fail to engage a large segment of those at risk. As a result, national suicide prevention strategies now emphasize expanding beyond hospital and clinic settings into the community [5]. The VA’s public health roadmap calls for proactive communitybased prevention efforts to complement clinical care (VA, 2019). In practice, a comprehensive public health approach means addressing suicide risk factors at multiple levels—individual, community, societal—and implementing universal, selective, and indicated interventions in communities [6].

Peer support has emerged as a promising community-based strategy for veteran suicide prevention. Peer support involves trained individuals with lived experience (in this case, fellow veterans) providing social and emotional support to others with similar experiences. Such approaches leverage the unique rapport and trust that exist between veterans with shared combat experiences. Research indicates that peer support interventions can effectively engage veterans and potentially reduce suicide risk. For example, a pilot randomized trial found that when veterans hospitalized for suicidal ideation received support from veteran peer specialists in addition to usual care, they gave highly positive feedback about the peer mentors’ ability to connect with and support them [7]. The presence of a fellow veteran who “speaks the same language” can foster hope and reduce stigma around seeking help [8]. Communitybased veteran peer efforts are increasingly recognized as a promising public health approach to preventing veteran suicide, complementing clinical services by reaching veterans in their everyday environments. Indeed, peer-led programs can engage veterans who might not otherwise seek formal mental health care, thereby filling a critical gap in the prevention continuum. The importance of community collaboration is also reflected in the VA’s calls to action in the 2024 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual report. More work is needed to evaluate promising community-based suicide prevention strategies for effectiveness/scalability as also noted in the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention.

In addition to peer support, holistic models that address the full spectrum of a veteran’s well-being are important in trauma recovery and suicide prevention. Operation Resilience is conceptually informed by a biopsychosocial-spiritual model of care. This model recognizes that biological, psychological, social, and spiritual factors are interconnected contributors to health and recovery [9]. Combat trauma and military service more broadly can affect not only a veteran’s mental and physical health but also their sense of meaning, purpose, and connection to others. Interventions that incorporate spiritual or support alongside psychosocial care have shown promise in helping veterans heal. For instance, programs offering spiritual care for combat trauma, such as faith-based peer groups, report that participants find meaning-making, forgiveness, and reconciliation to be valuable in their healing process [10]. Addressing these spiritual or moral dimensions can bolster resilience and hope, which are protective against suicide.

Operation Resilience was developed against this background to help prevent suicide among veterans exposed to combat trauma by combining community-based peer support with a biopsychosocialspiritual approach. The program’s design draws on evidence that peer connection, holistic resilience-focused activities, and community engagement can together reduce risk factors such as isolation and hopelessness and strengthen protective factors like social support, coping skills, and purpose in life for veterans. The purpose of this article is to describe the Operation Resilience program and present an evaluation of its implementation and outcomes. We hypothesize that participants in Operation Resilience will show improved psychosocial well-being including reduced distress and loneliness, and increased coping and sense of purpose and that the program will be feasible and acceptable to veterans seeking care and support outside traditional clinical settings.

Methods

While to date, there have been 14 separate Operation Resilience reunions, for the purpose of this paper, we examine the reunion attended by veterans from a single unit. We conducted a program evaluation of Operation Resilience using a pre-post, communitybased approach. The intervention took place in Charlotte, North Carolina, at various locations throughout the city where program activities were held. Participants were U.S. military veterans from a specific unit with a history of combat trauma and elevated suicide risk factors (such as past trauma-related mental health issues or expressions of hopelessness). Inclusion criteria included being a post-9/11-era veteran, having self-reported exposure to combatrelated traumatic events, and willingness to engage in peer support. Veterans were recruited by the Independence Fund through social media and peer support methods using word-of-mouth referrals. All participants provided informed consent.

Intervention – Operation Resilience Program

Operation Resilience is a community-based, peer-support intervention lasting four days. The program is co-led by resilience subject matter experts alongside trained veteran peer mentors who have themselves coped with combat-related trauma. The intervention consists of a long weekend of group sessions followed by supplemental check-ins, emphasizing meaning making activities, meals and social time a comprehensive resilience model. Key components of the Operation Resilience program include:

• Biopsychosocial-Spiritual Resilience Curriculum: A structured curriculum consisting of four days of programming addressing holistic resilience. Topics are organized around the biopsychosocial-spiritual model and include managing stress and post-traumatic symptoms (biological/psychological), rebuilding family and community relationships (social), and exploring sources of meaning, hope, or spiritual resilience (spiritual). For example, one session focuses on coping skills for anxiety or insomnia (biological aspect), while another might involve a discussion or storytelling exercise about finding purpose after military service (spiritual aspect). This integrated approach is based on the principle that recovery from trauma involves healing the “whole person,” including mind, body, social connections, and spirit [9].

Throughout the program, facilitators documented attendance, engagement levels, and any adverse events. A clinical consultant was onsite for risk management if a participant exhibited severe distress. This structure ensured that while Operation Resilience operated outside a hospital setting, safety protocols were in place for crisis situations.

Measures and Data Collection

We used a mixed-methods approach to evaluate outcomes. We assessed biopsychosocial-spiritual health through a composite survey capturing self-reported physical health, mental well-being, social connectedness, and sense of purpose or spiritual well-being. In addition, participants rated their satisfaction with the program and the perceived helpfulness of various components on a Likert scale. Demographic information, including age and service branch, was also collected.

Qualitative data were gathered through open-ended survey responses and a follow-up focus group conducted approximately three months after the intervention. The focus group aimed to explore participants’ longer-term perceptions of Operation Resilience’s impact and to identify recommendations for future program improvements.

For quantitative data, we conducted pre- vs. post-program comparison surveys from the Operation Resilience participants focusing on perceived social support/connection, satisfaction with health services, and resilience (Brief Resilience Scale–style items; negative items reverse-coded for the composite). Because responses were unpaired and Likert-type, we used Welch’s t-tests as the primary analyses with Mann–Whitney U tests as a robustness check; we report effect sizes as Cohen’s d (independent samples) and rankbiserial r for U tests.

A mixed-methods design was selected because Operation Resilience is a complex, community-based intervention that influences multiple domains of veteran well-being, including social connection, coping, and meaning-making. Quantitative data allowed us to examine directional changes in perceived support and resilience, while qualitative data provided insight into participants’ lived experiences, mechanisms of change, and program acceptability. Mixed-methods designs are recommended for evaluating multi-component publichealth and behavioral health programs, as they offer a more comprehensive understanding of both outcomes and processes than either method alone [11-13].”

Results

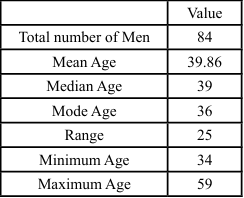

Demographic information was collected from both the pre- and postintervention surveys. While the samples were not linked individually, the overall participant groups were similar in composition. Table 1 displays a summary of the demographic characteristics for participants who completed the pre- and post-surveys. A total of 84 men attended operation resilience, whose ages ranged from 34 to 59 years, yielding a range of 25 years. The mean age of participants was approximately 39.9 years, with a median age of 39. The most frequently occurring age (mode) was 36, suggesting a slight skew toward the younger end of the distribution. The standard deviation was approximately 4.9, indicating moderate variability around the mean. This distribution of attendees was largely composed of middleaged adults, with a concentration in the mid-to-late 30s and early 40s. The relatively tight standard deviation and central tendency measures reflect a homogeneous group in terms of age, though the presence of older participants (e.g., 52, 58, and 59) contributes to a broader overall range.

Social support & connection. Perceived support from battle buddies increased significantly from pre to post (pre: M=4.17, SD=0.89, n=64; post: M=4.52, SD=0.73, n=107), t(~153)=2.92, p=.004, d=0.45 (small–medium), with convergent Mann–Whitney U (p=.006, r=0.22). Family/friend support (pre: 4.38±0.89; post: 4.36±0.86) and overall connectedness to family/friends/community (pre: 3.92±1.02; post: 3.79±1.06) showed no statistically significant change (ps≥.29; |ds|≤0.13).

Resilience. At the item level, resilience statements showed no significant pre/post differences (|ds| ≤ 0.19; all ps ≥ .07). A Brief Resilience Scale-style composite (three positively worded and two negatively worded items, reverse-coded; available items only) likewise showed no significant change (pre: M=3.57, SD=0.83, n=65; post: M=3.53, SD=0.81, n=108), Welch’s t=0.30, p=.76, d=- 0.05; Mann–Whitney U p=.85.

Interpretation. Within the constraints of an unpaired, singlegroup pre/post design, Operation Resiliency was associated with a meaningful improvement in perceived peer (battle buddy) support—a known protective factor for psychological health and suicide risk— while other domains (family support and resilience) were statistically unchanged over the brief program interval. Given the design, results should be interpreted as pre-post change within participants exposed to the program rather than causal effects. Future evaluations with matched (paired) data, multiple follow-ups, and comparison groups would enhance causal inference and sensitivity to change in resilience and connectedness.

Qualitative data from surveys and the focus group were analyzed using thematic analysis. Two independent coders identified recurring themes related to participants’ perceived impacts (e.g., “increased hope,” “feeling understood by peers,” “renewed sense of purpose”). A consensus approach was used to refine code definitions and ensure reliability in theme identification. Triangulation of quantitative and qualitative findings provided a richer understanding of how Operation Resilience affected the veterans and which aspects were most beneficial.

Discussion

The pilot evaluation of Operation Resilience demonstrates that a community-based, peer-co-led intervention can be feasibly implemented and is highly acceptable to veterans with combat trauma. Quantitative analyses showed statistically significant improvements in social support, connectedness, and resilience following the program. Effect sizes ranged from small to moderateto- large, indicating meaningful changes in veterans’ perceptions of their well-being and support systems.

• Social Support/Coping Pre-Post Questions

• How Supported do you feel by your family and close friends?

• How Supported do you feel by your battle buddies?

• How satisfied are you with your current support system as a whole (family, friends, neighbors)?

• How connected do you feel to your family, friends, and community?

• I am knowledgeable about effective coping skills

• I am competent in the practice of effective coping skills

• I am comfortable practicing effective coping skills

• I tend to bounce back quickly after hard times

• I have a hard time making it through stressful events

Qualitative data enriched these findings, revealing that participants valued both practical coping skills and the deep camaraderie fostered by the program.

Themes such as feeling “understood,” reconnecting with a sense of military family, and gaining concrete strategies for managing stress and trauma highlight the unique contribution of peer-led interventions in addressing veteran mental health.

Themes from the qualitative analysis of open ended comments on the post test:

• Reconnection & cohesion as the catalyst: Reuniting with “fellow veterans/brothers in arms” and “seeing the guys I have not seen in years” reignited trust and willingness to engage.

• Blended format lowers defenses: The mix of workshops + laid-back bonding/fun “allowed people to open up” and “just talking” to flow naturally.

• Facilitated, structured reflection on the deployment arc: Guided discussions (pre-/during-/post-deployment) and clinician-led group sessions enabled meaning-making and perspective taking.

• Normalization through shared perspectives: Hearing others’ stories revealed “we all have the same issues,” reducing isolation/stigma and validating diverse coping responses.

• Insight and movement toward healing: Participants reported new awareness (“I’m still carrying a lot of anger”), answers/ clarity to long-standing questions, and practical ways to “deal with tough times.”

In addition to aligning with emerging veteran-focused peer support literature, these findings are consistent with broader global evidence demonstrating the value of community-based mental health approaches. Systematic reviews show that community education, lay health workers, and peer mutual-aid models can improve access, strengthen social connection, and enhance psychological wellbeing, particularly in low-resource or underserved settings [14-16]. The WHO’s framework similarly underscores that non-specialist, community-delivered interventions can meaningfully extend the reach of traditional health systems [17].

Integration with Existing Literature

These findings align closely with emerging research on the benefits of peer support and holistic public health approaches for veterans. Previous studies have shown that peer-led interventions can successfully engage veterans who might otherwise avoid traditional clinical care. As Pfeiffer et al. [7] reported, veterans often value the authentic connection and trust established through shared experiences, which can reduce stigma and foster hope.

Moreover, Operation Resilience’s incorporation of a biopsychosocialspiritual framework addresses a critical gap in veteran care. Many veterans struggle not only with psychological symptoms but also with existential questions, moral injury, and the loss of meaning following military service. By integrating discussions of purpose, spirituality, and connection, Operation Resilience mirrors findings from faith-informed veteran programs where participants attribute healing in part to spiritual exploration and peer fellowship [18,19].

The program’s holistic approach underscores a growing recognition that recovery from trauma must address the “whole person”— mind, body, relationships, and spirit. This integrative focus may be especially important for preventing suicide, as a sense of meaning and belonging are known protective factors against suicidal ideation.

Public Health Implications

The success of Operation Resilience has several practical implications:

• Community-Based Delivery: The program provides proofof- concept that suicide prevention can be effectively delivered outside clinical institutions. Given that a substantial portion of veterans do not engage with VA or other formal healthcare services, community-based initiatives like Operation Resilience are critical for reaching underserved populations.

• Scalability and Cost-Effectiveness: The co-peer-led model empowers veterans to become helpers within their own communities. With appropriate training and oversight, veteran peers can sustainably deliver interventions, reducing reliance on limited clinical resources.

• Holistic Engagement: Integrating biopsychosocial and spiritual elements improved engagement and retention in the program. Participants were drawn not only to symptom management strategies but also to broader discussions about identity, purpose, and community. Such holistic models may be more resonant and impactful than narrowly clinical approaches.

• Sustainability Through Connection: The follow-up focus group revealed that veterans continue to maintain supportive relationships formed during Operation Resilience, often through group chats or social media. Sustaining these connections could amplify the program’s impact over time and foster ongoing resilience.

Challenges and Lessons Learned

Despite its successes, Operation Resilience faced several challenges:

• Training and Boundaries: Peer facilitators, while highly effective, are not clinicians and require clear protocols for handling crises. The presence of a clinical consultant during the program was essential for safety.

• Measurement Limitations: The small sample size limited statistical power, and the lack of a control group prevents causal inference. Future research should consider randomized controlled designs and long-term follow-up to better assess impact.

• External Environmental Factors: While programming is scheduled for the majority of the day, participants also have unstructured free time. In some instances, how participants spend this time may impact engagement and processing in groups (e.g., lack of sleep, social activities, etc.)

Limitations

This pilot evaluation has notable limitations. The sample was selfselected and may reflect veterans already open to peer support and community engagement, potentially biasing results. Additionally, improvements observed post-intervention could be influenced by factors such as participants’ pre-existing motivation, the novelty of the program, or other concurrent services.

Further, Operation Resilience was conducted in a single geographic location, raising questions about generalizability to other veteran populations or regions. Future studies should replicate the program in diverse settings to examine its broader applicability.

The sample for this pilot consisted entirely of men, ages 34-59 reflecting the composition of the participating unit. While this aligns with the demographic reality of many combat arms units, it limits the generalizability of findings to other age groups and women veterans. Women experience trauma, social support, and recovery processes in ways that may differ meaningfully from their male peers, and suicide risk patterns also vary by gender. Future evaluations should intentionally include women veterans either through mixed-gender cohorts or women-specific Operation Resilience programming to better assess the model’s relevance, effectiveness, and acceptability across genders.

Future Directions

Future studies should incorporate more rigorous designs, including the use of matched comparison or control groups to strengthen causal inference. In addition, evaluating long-term outcomes at 6, 12, and 24-month intervals would help determine whether gains in peer support, connection, and coping persist over time and whether the program influences downstream outcomes such as help-seeking, functional status, or suicidal ideation. Including longitudinal data and comparison conditions would substantially enhance the evidence base for community-based peer interventions like Operation Resilience. Future efforts should also include randomized controlled trials comparing Operation Resilience with standard care or alternative interventions. Exploring the methods to formally integrate peerled initiatives into the Department of Defense or VA systems for greater reach and sustainability would also help sustain the program efforts. Researchers should evaluate complementary programming for spouses and family members, as requested by participants, to enhance family resilience and understanding. Finally, researchers should determine if it is possible to replicate Operation Resilience, for first responders and other occupations impacted by trauma to foster a nationwide network of peer-driven, holistic support.

Conclusion

Operation Resilience demonstrates the promise of community-based, peer-driven interventions for improving veterans’ mental health and reducing suicide risk. By combining peer support, holistic wellness activities, and a focus on meaning and belonging, the program represents a paradigm shift in veteran care. Early evidence suggests that such models can engage veterans in ways that traditional clinical services sometimes cannot, offering practical tools, hope, and human connection. As veteran suicide remains a pressing public health crisis, Operation Resilience stands as an innovative example of how community, compassion, and shared experience can light the path toward healing and resilience.

Competing Interests:

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgement:

This work is supported by the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC), Taiwan (NSTC 114-2410- H-006-049). I thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments.

References

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. (2019). National strategy for preventing veteran suicide: 2018–2028. View

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. (2024). 2024 National veteran suicide prevention annual report. View

Luoma, J. B., Martin, C. E., & Pearson, J. L. (2002). Contact with mental health and primary care providers before suicide: A review of the evidence. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(6), 909–916. View

Denneson, L. M., Le, W., Pfeiffer, P. N., & Dobscha, S. K. (2023). Health care contacts prior to suicide among veterans receiving primary care. General Hospital Psychiatry, 82, 1–7.

Hoge, C. W., Castro, C. A., Messer, S. C., McGurk, D., Cotting, D. I., & Koffman, R. L. (2016). Deployment-associated mental health problems, treatment barriers, and stigma. Psychiatric Services, 67(8), 917–923.

Stone, D. M., Holland, K. M., Bartholow, B., & Crosby, A. E. (2017). Preventing suicide: A technical package of policy, programs, and practices. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. View

Pfeiffer, P. N., et al. (2019). Peer support interventions for adults with mental health disorders: A systematic review. General Hospital Psychiatry, 58, 1–8.

Bowersox, N. W., et al. (2021). Peer-based interventions targeting suicide prevention: A scoping review. American Journal of Community Psychology, 67(1–2), 36–50. View

Koenig, H. G. (2012). Religion, spirituality, and health: The research and clinical implications. ISRN Psychiatry, 2012, Article 278730. View

Litz, B. T., Stein, N., Delaney, E., Lebowitz, L., Nash, W. P., Silva, C., & Maguen, S. (2009). Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: A preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(8), 695–706. View

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). SAGE. View

Palinkas, L. A., et al. (2011). Mixed method designs in mental health services research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(1), 44–53. View

Fetters, M. D., Curry, L. A., & Creswell, J. W. (2013). Achieving integration in mixed methods designs—Principles and practices. Health Services Research, 48(6), 2134–2156. View

Barnes, L. A., et al. (2018). Community health workers’ role in mental health care in low-resource settings: A systematic review. The Lancet Global Health, 6(10), e1122–e1131.

Ehsan, A. M., et al. (2019). Social capital and health: A systematic review of systematic reviews. Sociology of Health & Illness, 41(5), 951–965. View

Repper, J., & Carter, T. (2011). A review of the literature on peer support in mental health services. Journal of Mental Health, 20(4), 392–411. View

World Health Organization. (2022). mhGAP intervention guide for mental, neurological and substance use disorders in nonspecialized health settings (Version 3.0). WHO. View

Currier, J. M., et al. (2017). Spirituality, meaning, and posttraumatic stress: Assessing the psychometric properties of the Spiritual Meaning Scale in veterans. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 9(1), 98–105. View

Nieuwsma, J. A., et al. (2020). Support for moral injury among veterans and service members: A systematic review. Psychological Services, 17(3), 310–322. View