Journal of Social Work and Welfare Policy Volume 3 (2025), Article ID: JSWWP-175

https://doi.org/10.33790/jswwp1100175Research Article

Childhood Emotional, Physical, and Sexual Abuse as Predictors of Adult Behavioral Outcomes: Implications for Trauma-Informed Clinical Practice

Darron Garner1, PhD, LCSW-S, Jackson de Carvalho2*, PhD, and Beverly Spears3, PhD

1Associate Professor of Social Work, Department of Social Work, Prairie, Prairie View A&M University, Prairie View, Texas 77446, United States.

2Professor & MSW Program Director, Prairie View A&M University, Prairie View, Texas 77466, United States.

3Assistant Professor & MSW Field Director, Prairie View A&M University, Prairie View, Texas 77466, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Jackson de Carvalho, PhD, Professor & MSW Program Director, Prairie View A&M University, Prairie View, Texas 77466, United States.

Received date: 11th November, 2025

Accepted date: 09th December, 2025

Published date: 11th December, 2025

Citation: Garner, D., Carvalho, J. D., & Spears, B., (2025). Childhood Emotional, Physical, and Sexual Abuse as Predictors of Adult Behavioral Outcomes: Implications for Trauma-Informed Clinical Practice. J Soci Work Welf Policy, 3(2): 175.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Experiencing maltreatment in childhood is a major predictor of several adverse behavioral and psychosocial outcomes that can last throughout a person's life. Such early trauma can significantly affect an individual's emotional well-being, relationships, and overall mental health, often resulting in a series of challenges that continue into adulthood. Over a period of one year, this quantitative study investigated how emotional, physical, and sexual abuse independently affect five adult behavioral outcomes—self-injury, substance misuse, problems at school or work, misdemeanor crimes, and felony crimes—among adult women in community behavioral health settings. Using validated multi-item scales from a trauma outcomes dataset with 220 participants and a Cronbach alpha of 0.83, this study revealed a concerning trend. Emotional abuse was consistently linked to higher behavioral risks across all domains, accounting for approximately 2% to 19% of the variance in the outcome measures, even after controlling for the effects of physical and sexual abuse. Additionally, physical abuse was found to predict substance misuse. These findings underscore the crucial yet often overlooked role of emotional maltreatment in trauma-informed assessments and interventions. The study's implications for clinical social work practice, treatment planning, and workforce development are significant and should engage professionals in the field.

Keywords: Emotional Abuse, Trauma-Informed Care, Behavioral Outcomes, Complex Trauma, ACE Framework, Polyvictimization, Social Work Practice, Women’s Mental Health

Introduction

Childhood abuse is not just a significant, but an urgent public health issue in the United States. In 2020 alone, Child Protective Services (CPS) investigated 3.5 million unique cases [1]. The effects of childhood abuse (CA) on survivors can last a lifetime, leading to an increased risk of various maladaptive health outcomes in adulthood. These outcomes include psychological disorders such as anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [2], as well as physical health issues like chronic pain, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

The wide range of potential health consequences that follow childhood abuse is associated with increased healthcare utilization and costs for survivors. However, understanding the mechanisms that connect childhood abuse to poor health outcomes in adulthood could lead to significant improvements. This could benefit not only the vulnerable individuals who have experienced CA but also the broader public, offering hope for a healthier future.

The existing literature is replete with studies that confirm the significant impact of childhood abuse and neglect on adult functioning, emotional regulation, and interpersonal behavior. While numerous studies underscore the cumulative effects of adverse childhood experiences [3,4], there has been comparatively less emphasis on the specific predictive role of emotional abuse, which frequently remains overshadowed by physical and sexual trauma.

Emotional maltreatment, defined by invalidation, humiliation, and verbal degradation, has been associated with difficulties in emotional regulation, self-harm, and challenges in relationships and work settings [5]. For instance, adults who experienced emotional abuse in childhood may struggle with self-esteem issues, have difficulty forming and maintaining healthy relationships, and may exhibit self-destructive behaviors. Social work practitioners increasingly encounter adults with complex trauma histories that are intertwined with behavioral issues. However, current practice models and screening protocols often downplay emotional abuse relative to physical or sexual trauma [6].

Childhood abuse is recognized as a significant risk factor for the development of psychological issues in adulthood, mainly due to its effects on fear learning processes. A study by Heck and Handa [7] showed that individuals who have experienced childhood abuse often display heightened sensitivity to threats from emotionally neutral stimuli during fear learning tasks. This is evidenced by altered startle responses that do not adjust over time. Additionally, these individuals tend to struggle to distinguish between fear and safety cues and have difficulty extinguishing learned fear responses.

Gaining a deeper understanding of the factors affecting fear learning processes in female survivors of childhood abuse could improve our understanding of why they are more vulnerable to negative health outcomes later in life. Furthermore, this knowledge could help in the early identification of at-risk individuals, highlighting the importance of proactive measures in addressing the consequences of childhood abuse.

Recognizing the distinct predictive power of various types of abuse is not just important, but crucial. It can improve targeted assessments, prioritize treatment, and inform trauma-informed interventions that are consistent with the NASW Standards for Clinical Social Work in Social Work Practice [8]. As professionals and researchers, our role in this process is significant, and our contributions can make a real difference.

Literature Review

A thorough review of the pertinent literature illustrates that childhood abuse encompassing emotional, physical, and sexual abuse remains a substantial global public health concern, yielding enduring behavioral and psychosocial repercussions. A meta-analysis conducted by Stoltenborgh et al. [9] revealed that nearly one in four adults reported experiencing physical abuse, one in five reported sexual abuse, and as many as one in three experienced emotional maltreatment. Additionally, Finkelhor et al. [10] noted that these forms of abuse rarely occur independently; instead, they often present together as polyvictimization, leading to complex trauma profiles that increase the likelihood of behavioral risks. Despite this interrelation, emotional abuse is often overlooked in both clinical practice and research, even though its prevalence frequently exceeds that of physical or sexual abuse [11].

Emotional abuse, a pattern of verbal aggression, demeaning humiliation, and chronic rejection, can profoundly undermine a child's sense of self-worth and security [12]. As professionals and academics, it's crucial to understand the significant correlation between emotional maltreatment and a variety of adverse outcomes, including emotion dysregulation, deep-seated depression, self injurious behaviors, and challenges in forging healthy interpersonal relationships [13,14]. Teicher and Samson [15] shed light on the neurobiological ramifications of such abuse, noting enduring modifications within the brain's limbic-prefrontal circuitry. These alterations contribute to persistent difficulties in impulse control and emotional regulation. This understanding resonates with Linehan’s [16] biosocial theory, which posits that chronic invalidation can lay the groundwork for self-harm and other perilous behaviors. Recent population-based studies suggest that the effects of emotional abuse extend into adulthood, revealing it as a significant predictor of functional impairment long after other forms of trauma are taken into account [17,18]. As professionals, we have a responsibility to address emotional abuse and its long-term effects.

Conversely, physical abuse has been strongly associated with patterns of substance use and aggressive behavior, mediated mainly by pathways involving heightened stress reactivity and maladaptive coping mechanisms [19,20]. The activation of the hypothalamic- pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, coupled with alterations in the brain’s reward circuitry, a complex system in the brain that reinforces certain behaviors, intensifies an individual's susceptibility to addiction and impulsiveness. Similarly, the aftermath of sexual abuse is closely linked to the development of depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and instability in personal relationships [21]. However, when emotional factors are explored, the connection between sexual abuse and externalizing behaviors often weakens [22]. These findings imply that the psychological ramifications and enduring effects of emotional abuse may wield a greater influence on behavioral outcomes than the physical severity of abuse experienced.

Beyond the psychological and behavioral sequelae of emotional abuse, a growing body of attachment-oriented neuroscience underscores how early relational trauma is instantiated in the developing brain. Perry’s Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics (NMT) highlights that chronic threat and caregiver misattunement alter the organization of subcortical and limbic systems responsible for arousal modulation and attachment security, with downstream effects on executive functioning and behavioral control into adulthood [23]. Schore’s work on right-brain affect regulation similarly demonstrates that repeated experiences of shame, rejection, and relational rupture disrupt orbitofrontal–limbic integration, predisposing survivors to emotion dysregulation and impulsive or self-destructive coping [24]. Clinically, these neurodevelopmental findings converge with Rothschild’s somatic trauma framework, which emphasizes that trauma is encoded not only cognitively but in autonomic patterns of hyper- or hypoarousal that manifest as chronic tension, numbing, startle, or dissociation in everyday functioning [25].

Recent population-level work further supports reframing emotional maltreatment as a core public health priority rather than a secondary concern. Mathews and Dube [5] argue that emotional abuse has been systematically deprioritized in child protection systems despite mounting evidence of its pervasive health and economic burden, calling for a paradigm shift in policy and prevention. Complementing this risk-focused literature, Fares-Otero and colleagues’ systematic review of child maltreatment and resilience in adulthood indicates that emotional abuse is strongly associated with impaired emotion regulation, even when other trauma types are considered, while also highlighting resilient trajectories among some survivors [26]. The present study extends this work by quantifying how emotional abuse independently predicts multiple domains of behavioral functioning in a racially diverse female sample, underscoring the need to integrate neurobiological, somatic, and resilience-oriented perspectives into trauma-informed social work practice.

Theoretical Perspective

From a theoretical standpoint, this study is anchored in Trauma Informed Resilience Theory, as posited by SAMHSA [27]. This theory posits that adaptive functioning in individuals who have experienced trauma is contingent upon the interaction between risk factors—such as early maltreatment and chronic stress— and resilience processes, which encompass emotional regulation, relational safety, and meaning-making. In this context, emotional abuse has been identified as a factor that compromises key resilience mechanisms—specifically, emotional regulation, attachment security, and self-efficacy—which are essential for mitigating maladaptive outcomes in adulthood. Furthermore, Developmental Trauma Theory [28] underscores that prolonged emotional invalidation can disrupt neurobiological stress systems, resulting in challenges with behavioral control and social functioning. Collectively, these models suggest that the repercussions of emotional maltreatment extend beyond mere psychological distress to encompass behavioral dysregulation, substance misuse, and impaired occupational or legal functioning.

This conceptual framework aligns with the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) model [3], which delineates a dose-response relationship between cumulative childhood trauma and subsequent health and behavioral outcomes. While many studies based on adverse childhood experiences (ACE) support this link, there is still a lack of research that separately examines the predictive power of emotional abuse after accounting for physical and sexual trauma [6]. Additionally, there is a paucity of studies focusing on racially diverse female samples, despite evidence indicating that women of color are subjected to intersecting interpersonal and structural traumas [29]. Consequently, there is an imperative for quantitative analyses that isolate emotional abuse as a distinct predictor of adult behavioral functioning in culturally diverse, community-based contexts.

This study endeavors to differentiate emotional, physical, and sexual abuse as independent predictors, thereby facilitating a more nuanced understanding of how each type contributes to distinct patterns of behavioral risk. Specifically, the study aims to examine whether emotional, physical, and sexual abuse independently predicts five domains of adult behavioral functioning: self-injury, substance misuse, problems in academic or occupational settings, misdemeanor behavior, and felony behavior, utilizing empirically validated scales derived from a trauma outcomes dataset.

It is hypothesized that emotional abuse will independently predict self-injury and substance misuse beyond the influences of physical and sexual abuse, and that emotional maltreatment will exhibit the most consistent association across all domains of behavioral functioning. The applied focus of this study is to elucidate how distinct patterns of abuse exposure relate to behaviors that frequently emerge in clinical social work settings, thereby informing trauma informed assessment and intervention practices.

Method

Participants and Setting

The data for this study were obtained from a secondary quantitative dataset collected between 2021 and 2023. This dataset was part of an institutional research initiative aimed at examining trauma and behavioral health outcomes among adults receiving community based services. The original study received approval from the Prairie View A&M University Institutional Review Board (IRB #21-047) and adhered strictly to ethical standards pertaining to research involving human participants. The dataset comprises 201 adult women who were receiving outpatient or community-based behavioral health services in a large metropolitan area in the southern United States. The age of participants ranged from 18 to over 55 years, with a mean age of 32.6 years (SD = 8.9). The sample was racially and ethnically diverse, with 59.7% identifying as Black/African American, 29.9% as Latina/Hispanic, 7.5% as White, and 3% as Other/Mixed Race.

The study utilized a purposive sampling strategy focused exclusively on women. This decision was made to address the disproportionate effects of emotional and interpersonal trauma on women within community behavioral health systems. By concentrating the analysis on women, the study sought to develop more homogeneous models of gendered trauma responses, such as self-harm and internalized distress. While this approach enhances the construct validity for trauma survivors in the female demographic, it is essential to recognize that it also limits the generalizability of findings to other genders, a limitation that is acknowledged in the Discussion section.

Measures

Locked multi-item composites were established for each construct through reliability analysis (Cronbach’s α ≥ .75 across scales). The following domains were examined:

• Childhood Emotional Abuse: five items reflecting verbal invalidation, belittlement, and psychological humiliation.

• Childhood Physical Abuse: five items assessing physical harm or threat of harm.

• Childhood Sexual Abuse: four items covering coercion, unwanted touching, or assault.

• Self-Injury: six items on self-harm, cutting, or suicide attempts.

• Substance Misuse: four items assessing drug or alcohol misuse.

• School/Work Problems: five items assessing absenteeism, conflict, or disciplinary issues.

• Misdemeanor and Felony Behavior: eight and seven items respectively, indicating low- and high-severity legal infractions.

Each subscale utilized five-point Likert-type response options, ranging from 1 (Never) to 5 (Frequently). To ensure the integrity of the results, mean composite scores were computed for each subscale provided that participants completed at least 80% of the items. Reliability analyses affirm that each item contributed meaningfully to its composite score, with Cronbach’s α values ranging from .78 to .88 for the abuse scales and from .75 to .85 for the outcome measures.

Analytic Strategy

All analyses were performed utilizing IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 28. We began by computing descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation coefficients for all composite variables. Subsequently, we estimated five multiple regression models, each predicting a distinct adult behavioral outcome: self-injury, substance misuse, academic or occupational difficulties, misdemeanor behaviors, and felony behaviors. The predictors we examined, including emotional abuse, physical abuse, and sexual abuse, were rigorously standardized (z-scores) to allow for a consistent comparison of effect sizes. A thorough analysis of the data indicated no issues concerning multicollinearity, as all variance inflation factors (VIFs) remained below the threshold of 5. The extent of missing data was minimal, constituting less than 5% for each variable. This situation was addressed with diligence by employing listwise deletion for cases that exhibited incomplete data for either the predictor or outcome variables, thereby preserving the integrity of the dataset.

Reliability and Descriptive Statistics

Cronbach's α values ranged from 0.78 to 0.88 for the abuse subscales and from 0.75 to 0.85 for the outcome measures, demonstrating strong internal consistency across the assessed constructs. Item total correlations confirmed that each retained item meaningfully contributed to its respective composite score. The average scores for the various types of abuse were moderate, with emotional abuse exhibiting a mean of 2.9 (SD = 0.9), physical abuse having a mean of 3.1 (SD = 1.1), and sexual abuse recording a lower mean of 1.7 (SD = 0.8). Among the outcome measures, self-injury displayed a mean of 2.8 (SD = 1.2), while problems related to school or work had a mean of 1.7 (SD = 0.9), indicating substantial variability. This data suggests that behavioral risks are most prominent in the domains of internalizing issues and functional impairment.

Regression Findings

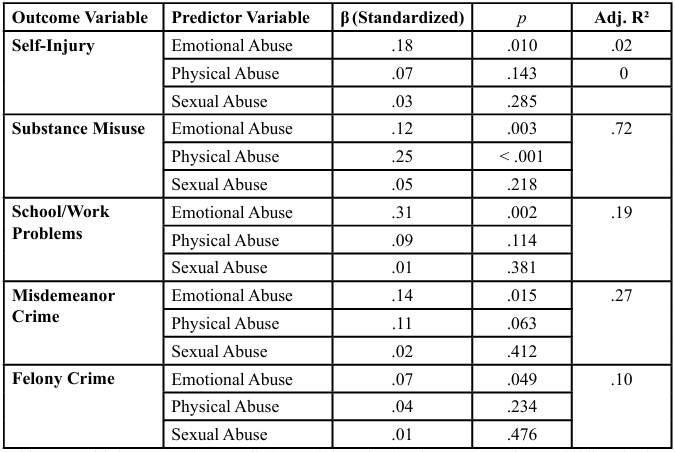

Table 1 presents a summary of standardized regression coefficients obtained from all outcome models. Emotional abuse has been identified as a significant independent predictor across various domains.

Sexual abuse did not significantly predict any behavioral outcome once emotional and physical abuse were entered together, indicating that emotional maltreatment accounted for unique and substantial differences in adult behavioral functioning.

Table 1: Multiple Regression Predicting Adult Behavioral Outcomes from Childhood Abuse Subtypes (N = 201)

Results

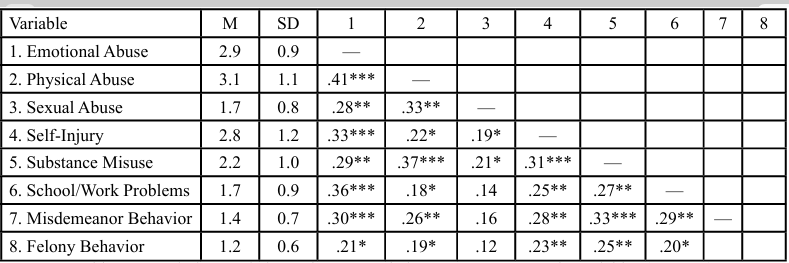

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Table 2 presents the means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations among all study variables. Emotional, physical, and sexual abuse were moderately correlated with one another (rs = .28–.41), reflecting the expected co-occurrence of maltreatment types. Emotional abuse showed the strongest positive associations with self-injury (r = .33, p < .01), substance misuse (r = .29, p < .01), and school/work problems (r = .36, p < .001). The correlations suggest that individuals reporting higher levels of emotional maltreatment also exhibited greater behavioral and functional risk in adulthood.

Regression Analyses

Emotional abuse was a strong predictor of adult behavioral risks in every model, independent of physical and sexual abuse (see Table 1). Emotional maltreatment accounted for unique variance in self-injury (β = .18, p = .010), substance misuse (β = .12, p = .003), and school or work-related problems (β = .31, p = .002). It also showed modest associations with misdemeanor behavior (β = .14, p = .015) and felony behavior (β = .07, p = .049). When age and racial identity were included as covariates, the strength and significance of the effects of emotional abuse remained stable, indicating that these predictive relationships were not artifacts of demographic composition.

Standardized beta values of .10 to .30 indicate small to moderate effects [30], meaning emotional abuse contributes modestly to behavioral variance alongside other trauma types. The strongest standardized effect (β = .31) was seen in school or work-related problems, highlighting functional impairments linked to ongoing emotional invalidation and reduced self-efficacy.

Adjusted R² values varied from .02 to .72 across models. The notably high adjusted R² of .72 for the substance misuse model likely reflects shared variance between emotional and physical abuse, as these forms often co-occur and contribute to similar coping mechanisms, such as substance use. Variance inflation factors (VIFs < 5) indicated acceptable levels of multicollinearity, but future studies using structural equation modeling could better clarify these overlapping effects. Physical abuse maintained a unique and strong relationship with substance misuse (β = .25, p < .001), which aligns with evidence that early physical trauma disrupts stress physiology, increasing vulnerability to addictive coping patterns [4, 20]. In contrast, although sexual abuse has been associated with numerous psychopathological outcomes in past research [21], it did not appear as a significant predictor when examined alongside emotional and physical abuse, suggesting overlapping variance or possible mediation through pathways of emotional maltreatment.

Overall, the results demonstrate that emotional abuse serves as a central organizing variable linking early trauma to later behavioral dysregulation. This supports conceptual models of “developmental invalidation” [16,28], in which ongoing emotional degradation impairs affect regulation, impulse control, and interpersonal trust, ultimately leading to maladaptive behavioral coping strategies.

Discussion

Emotional Abuse as the Core Predictor of Behavioral Dysregulation

The prevalence of emotional abuse across various behavioral domains aligns with research that identifies psychological maltreatment as one of the most reliable predictors of psychopathology, even when considering instances of physical or sexual trauma [15,22]. Emotional abuse typically involves prolonged exposure to feelings of shame, rejection, and coercive control, which can significantly undermine an individual's self-worth and hinder the development of effective emotional regulation strategies.

These dynamics reflect the principles of the developmental trauma model [28], which asserts that sustained emotional invalidation disrupts neural integration within the limbic and prefrontal systems, resulting in chronic states of hyperarousal and dissociation. Applying emotion regulation theory [16] provides insight into how such environments cultivate maladaptive coping mechanisms, which may manifest as self-injurious behavior, avoidance, or aggression when internal distress becomes overwhelming.

Emotional invalidation adversely affects an individual’s ability to recognize, tolerate, and regulate affective experiences, leading to what Linehan described as "emotion dysregulation syndromes." The present findings, where emotional abuse remained a significant predictor even after controlling for physical and sexual abuse, substantiate this mechanism: emotional trauma serves as a fundamental driver of self-destructive and risk-oriented behaviors through impairments in self-regulation and identity coherence [12,13].

Substance Misuse and the Role of Physical Abuse

The robust correlation between physical abuse and substance misuse is consistent with well-established findings from the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) framework [3,19]and subsequent analyses from the National Comorbidity Survey [31]. Physiologically, recurrent physical harm activates the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, resulting in increased cortisol reactivity and dysregulation of the reward system [20]. These neurobiological adaptations enhance the vulnerability to substance use as a maladaptive regulatory strategy.

Psychologically, survivors may resort to the consumption of alcohol or drugs in an attempt to mitigate intrusive memories, fear, or hypervigilance associated with trauma exposure. The coexistence of emotional and physical abuse among participants highlights the phenomenon of polyvictimization [10], where multiple forms of maltreatment interact synergistically to heighten behavioral vulnerability. This convergence likely accounts for the high adjusted R² (.72) observed in the substance misuse model, which indicates shared variance between emotional and physical abuse. Notably, multicollinearity diagnostics (Variance Inflation Factors < 5) confirmed the statistical independence of these variables, providing reassurance about the robustness of the research. Future studies could apply structural equation or mediation models to clarify interactions among these factors.

Functional Impairments: School and Work Problems

Emotional abuse was found to be a significant predictor of both academic and occupational challenges, aligning with longitudinal studies that demonstrate a connection between early emotional neglect and deficiencies in executive functioning, motivation, and social competence [4,32]. Chronic psychological invalidation diminishes the sense of agency essential for persistence and achievement, resulting in underperformance or interpersonal conflicts within academic and workplace environments. Within the context of the trauma-informed resilience framework [27], this phenomenon indicates that survivors’ adaptive capacities may be hindered by internalized shame and relational mistrust. For social work practitioners, these insights underscore the necessity for interventions aimed at rebuilding self-efficacy and recognizing survivors’ potential for goal-directed behavior within supportive frameworks.

Legal Outcomes: Misdemeanor and Felony Behaviors

The associations between emotional abuse and criminal behaviors, while less robust, correspond with existing literature that links early emotional neglect to impulsivity, antisocial characteristics, and externalizing issues [33,34]. Unacknowledged trauma exposure can manifest as oppositional or risk-seeking behaviors, serving as a displaced expression of unresolved emotional distress. The developmental trauma model posits that unintegrated affective states often present behaviorally rather than verbally, a phenomenon evident in externalizing symptoms such as aggression or substance misuse. These findings highlight the importance of trauma-informed criminal justice strategies that focus on emotional injuries instead of just behavioral compliance, guiding future policy and practice.

The current findings, which closely align with population-based studies such as the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study [3] and the National Comorbidity Survey Replication [31], shed new light on the cumulative impact of childhood adversity on adult psychopathology and behavioral dysfunction. This study shows that emotional abuse significantly affects behavior, even when other traumas are present. As a result, these findings strengthen the relevance of ACE research in real-world clinical contexts, showing that emotional maltreatment—though less apparent—is a key factor in behavioral difficulties.

Given that nearly 90% of the sample identified as Black or Latina, it is essential to interpret the findings within a sociocultural framework that recognizes the interplay of racialized trauma, gender-based vulnerability, and socioeconomic stressors. Research consistently demonstrates that women of color disproportionately endure both interpersonal and structural trauma [6,29]. These intersecting contexts may exacerbate the effects of emotional maltreatment by limiting access to healing resources, perpetuating systemic invalidation, and elevating chronic stress exposure. Accordingly, trauma-informed social work practice must not only incorporate cultural humility and anti-oppressive frameworks but also stress the need for culturally sensitive practices, acknowledging that emotional abuse manifests not only within familial contexts but also within broader systems of marginalization.

Limitations

Several limitations should be considered. First, the study relied on self-report data, which can be affected by recall bias or underreporting due to stigma or memory suppression. Second, the cross-sectional design restricts the ability to infer causation; longitudinal studies are needed to confirm the temporal relationships between emotional abuse and adult behavior. Third, while the all-female sample strengthens the internal validity for understanding gender-specific trauma patterns, it limits the generalizability of the findings to men or gender-diverse populations. Finally, although the models accounted for key demographics such as age and race, other contextual factors, such as socioeconomic status and treatment history, were not included. Future research should use prospective, intersectional, and mixed-method approaches to better understand the experiences behind quantitative findings. Including neurobiological measures, qualitative narratives, and culturally relevant resilience indicators would further enhance our understanding of how emotional trauma impacts behavior across different social contexts.

Implications for Social Work Practice

The study's findings yield a series of insightful recommendations to enhance trauma-informed clinical social work practices. These recommendations, in harmony with the guidelines set forth by the Council on Social Work Education [35], Educational Policy and Accreditation Standards (EPAS), and the National Association of Social Workers [8] Standards for Trauma-Informed Care, underscore the vital need to weave evidence-based practices into the fabric of social work, adopt a holistic person-in-environment perspective, and embrace cultural humility. This multifaceted approach is essential for creating an environment that fosters safety, empowerment, and resilience among individuals who have experienced the profound impacts of trauma. As professionals in the field, it is our responsibility to implement these recommendations and make a significant difference in the lives of those affected by trauma.

By deepening our understanding of how these critical factors contribute to vulnerability to trauma-related disorders, particularly among those who have suffered childhood abuse, clinicians can refine their ability to identify at-risk individuals. This enhanced comprehension enables the development of more targeted interventions, thereby improving therapeutic outcomes for those who need support the most. Emotional abuse constitutes a significant yet often overlooked dimension of trauma, necessitating systematic assessment across all screening and intake procedures. The utilization of validated instruments, such as the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire [36], is imperative to capture the complexities of this form of maltreatment. In accordance with the Council on Social Work Education (CSWE) Competency 7, which emphasizes the assessment of individuals, families, groups, organizations, and communities, social workers are tasked with collecting multidimensional data that encompasses both overt and covert manifestations of trauma.

In addition to refining assessment content, trauma-informed social work requires operationalizing how progress is monitored over time. For clients whose histories include emotional abuse, practitioners can pair narrative assessment with standardized, repeatable measures that align with the behavioral outcomes identified in this study. For example, self-injury and suicidal behavior may be tracked using brief self-harm indices or items from validated instruments (e.g., NSSI or self-injury subscales), administered at intake and at regular intervals (e.g., every 4–6 weeks), with a pre-specified reduction in frequency or severity indicating clinically meaningful improvement. Substance misuse can be monitored using tools such as the AUDIT, DAST, or agency-approved substance use screeners, with baseline and follow up scores compared to determine whether coping has shifted away from alcohol and drug use.

Functional problems in school or work settings may be evaluated through simple practice-based measures: tracking absenteeism, disciplinary events, performance concerns, or interpersonal conflicts over time. Likewise, involvement in misdemeanor or felony behavior can be monitored via self-report and collateral information (probation reports, court records) while being interpreted through a trauma informed lens that recognizes the role of emotional invalidation in externalizing behavior. Across domains, clinicians can adopt explicit decision rules, for instance, re-assessing the treatment plan and consulting with supervisors if a client’s scores worsen or fail to improve after two or three measurement points. Embedding these EBP-aligned procedures into routine care allows practitioners to translate the current study’s regression findings into concrete, trackable indicators of risk reduction and recovery. For example, a clinic might commit to administering an emotional abuse–informed trauma screen (e.g., the CTQ emotional abuse subscale) and a brief behavior-risk checklist at intake, 3 months, and 6 months. A 30–50% reduction in self-injury incidents or substance-related crises over six months could be used as a threshold for “meaningful improvement,” prompting step-down in care, while unchanged or worsening patterns would trigger case review, supervision, and possible treatment intensification.

Clinicians need to recognize that clients frequently downplay the severity of psychological maltreatment in comparison to physical or sexual trauma. This minimization can be rooted in the normalization of verbal degradation and feelings of internalized shame. Therefore, culturally responsive assessment practices must include narrative based and relational inquiries that affirm clients' lived experiences, fostering a more empathetic and nuanced understanding of their circumstances. Evidence-based interventions such as Dialectical Behavior Therapy [16], Skills Training in Affective and Interpersonal Regulation [37], and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) are specifically designed to address emotion dysregulation, thereby linking emotional abuse to various behavioral risks. The integration of these therapeutic modalities aligns with CSWE Competency 8, which requires social workers to employ trauma-informed, theoretically grounded strategies aimed at restoring self-regulation, fostering relational trust, and enhancing coping capacities. This not only instills hope but also cultivates optimism for both clients and practitioners.

Supervisory practices should promote reflective supervision models that encourage practitioners to engage in the exploration of countertransference, empathic strain, and implicit biases when supporting clients who have encountered emotional abuse. The complexities associated with emotional maltreatment can elicit profound emotional reactions, potentially resulting in secondary trauma or moral injury among service providers [6]. As such, training programs ought to integrate trauma-informed principles throughout their curricula and field supervision, thereby reinforcing CSWE Competency 1, which underscores the importance of ethical and professional behavior through continuous self-reflection and resilience-building. Behavioral health agencies must institutionalize trauma-informed systems of care [27] across various service domains, including education, employment, housing, and the criminal justice system. The focus on interdisciplinary collaboration is vital to ensuring continuity of care and minimizing the risk of retraumatization. By embedding the five NASW trauma-informed principles, safety, choice, collaboration, trustworthiness, and empowerment, within coordinated service delivery frameworks, clients can effectively address functional impairments arising from emotional trauma, ultimately promoting reassurance and a sense of security.

Cultural Responsiveness

The predominance of Black and Latina women within the sample underscores the necessity for trauma-informed practices that incorporate cultural humility alongside Afrocentric healing frameworks [38,39]. These Afrocentric approaches, which are deeply rooted in African cultural heritage, prioritize community, spirituality, interdependence, and restoration. Such frameworks provide culturally relevant pathways for healing emotional wounds resulting from both interpersonal and systemic trauma. For instance, the communal emphasis inherent in these practices can be effectively applied in group therapy, while spirituality can be integrated into mindfulness methodologies. Additionally, the principle of interdependence can guide the establishment of strong support networks.

The integration of Afrocentric practices aligns with the Council on Social Work Education (CSWE) Competency 2: Engage Diversity and Difference in Practice, as it affirms cultural identity and addresses the compounded effects of racism, sexism, and classism on trauma recovery. Social work practitioners must adhere to the National Association of Social Workers [8] Standards for Cultural Competence in Social Work Practice, ensuring that interventions align with clients’ cultural worldviews and leverage strengths derived from collective and ancestral resilience. By embedding Afrocentric principles into trauma-informed care, practitioners can create environments that foster belonging and empowerment, countering the isolation often experienced in situations of emotional abuse.

Application

Field and Clinical Practice. In outpatient community mental health settings, social workers might implement a brief “emotional abuse module” within their intake and early treatment process. For example, during the first three sessions, clinicians intentionally ask behaviorally specific questions about invalidation, humiliation, chronic criticism, and emotional neglect, using non-pathologizing language about “stress” and “messages you grew up with,” for shame-based minimization. These narratives are then linked directly to concrete behavioral targets (e.g., self-injury, substance use, work problems), with the worker collaboratively developing 1–2 emotion-regulation or interpersonal effectiveness goals and tracking them using simple rating scales. Reflective supervision is used to help practitioners process countertransference, vicarious trauma, and implicit biases that may arise when working with survivors of emotional maltreatment, particularly women of color.

Social Work Education and Curriculum. At the MSW level, programs can integrate emotional abuse content across HBSE, practice, and field seminar courses. One concrete approach is to assign the current study alongside classic ACE research and neurobiological trauma readings (e.g., Perry, Teicher & Samson, Rothschild), then require students to complete a case formulation in which they (a) differentiate emotional, physical, and sexual abuse in a composite case; (b) identify specific behavioral outcomes linked to emotional maltreatment; and (c) design a brief, measurable intervention plan (e.g., DBT skills plus school/work advocacy) with proposed outcome measures. In field seminar, students can be asked to map one of their current clients’ ACE histories, code for emotional abuse indicators, and reflect on how these factors might be influencing present-day substance use, legal involvement, or occupational functioning. This moves the manuscript’s findings directly into workforce development and competency-based education.

Systems-Level Prevention and Policy. At the organizational and systems level, agencies can use these findings to justify revising screening protocols so that emotional maltreatment is not treated as a “soft” or optional category. For example, child welfare or community mental health systems could (a) add a required emotional abuse subscale to all standardized intake packets; (b) train staff in asking non-stigmatizing questions about invalidation and emotional control; and (c) develop flagging criteria so that elevated emotional abuse scores automatically trigger trauma-informed referrals and safety planning. At the prevention level, practitioners can partner with schools and community organizations to deliver parent education and social–emotional learning programs that explicitly address verbal aggression, shaming, and emotional neglect as forms of abuse, not just “strict parenting”, aligning with recent calls to prioritize emotional maltreatment in public health and child protection policy [5]. Linking these initiatives to resilience-building strategies (e.g., peer support groups, culturally rooted healing practices, Afrocentric group interventions) also reflects emerging evidence that resilient trajectories are possible even in the context of early maltreatment, particularly when supportive relationships and regulatory skills are strengthened.

The findings of this study hold considerable implications for screening, workforce development, and prevention strategies. The vital importance of early detection cannot be overstated. The integration of standardized emotional abuse assessments within community mental health and child welfare systems is crucial for enhancing early identification and facilitating appropriate service linkage. Furthermore, workforce development programs must incorporate trauma-informed and culturally responsive curricula to elevate practitioners’ competencies in emotional assessment, reflective supervision, and interprofessional collaboration. Lastly, prevention initiatives should focus on enhancing community-level resilience through mechanisms such as parent education, school- based socioemotional learning programs, and culturally tailored group interventions to disrupt the intergenerational transmission of emotional maltreatment. Together, these recommendations establish social work as a transformative discipline capable of effectively bridging research, practice, and policy to promote holistic healing and equity among trauma-affected populations.

Conclusion

The current findings markedly enhance our comprehension of the diverse impacts of childhood abuse, encompassing emotional, physical, and sexual forms, on adult behavioral outcomes. Notably, emotional abuse, frequently the most prevalent yet least recognized type of maltreatment, has emerged as the strongest predictor of behavioral challenges across multiple domains. This highlights the critical necessity for addressing this matter within trauma-informed assessments, preventive strategies, and treatment planning.

Moreover, these findings have significant clinical implications and underscore the vital role of social work educators in shaping the future landscape of the profession. Integrating emotional maltreatment research into curriculum, supervision, and ongoing training helps future practitioners meet CSWE [35] and NASW [8] standards for trauma-informed practice. It is essential for social work educators to prioritize emotional awareness, relational safety, and empowerment-based interventions as fundamental components of trauma-responsive care.

By aligning empirical evidence with pedagogical strategies, social work programs can cultivate a workforce that is not only clinically competent but also culturally responsive and ethically principled. This method, which emphasizes the integration of research into practice, prepares practitioners to effectively address and interrupt the intergenerational transmission of trauma through compassionate and evidence-based engagement.

Competing Interest:

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

NCANDS (2022). National Data Archive onChild Abuse and Neglect. Neglect Data System. View

De Bellis, M. D., & Zisk, A. (2014). The Biological Effects of Childhood Trauma. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 23, 185-222. View

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. View

Anda, R. F., Felitti, V. J., Bremner, J. D., Walker, J. D., Whitfield, C., Perry, B. D., Dube, S. R., & Giles, W. H. (2006). The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood: A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 256(3), 174–186. View

Mathews, B., & Dube, S. (2025). Childhood emotional abuse is becoming a public health priority: Evidentiary support for a paradigm change. Child Protection & Practice, 4, Article 100093View

Levenson, J. S., Willis, G. M., & Prescott, D. S. (2021). Trauma informed care: Transforming treatment for people who have experienced trauma. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 91(4), 1–13.

Heck, A. L., & Handa, R. J. (2019, January 1). Sex differences in the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis’ response to stress: an important role for gonadal hormones. Neuropsychopharmacology. Nature Publishing Group. View

NASW. (2021). NASW Standards for Clinical Social Work in Social Work Practice. National Association of Social Workers. View

Stoltenborgh, M., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2015). The neglect of child neglect: A meta analytic review of the prevalence of neglect. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48(3), 345–355. View

Finkelhor, D., Ormrod, R., & Turner, H. (2007). Polyvictimization and trauma in a national longitudinal sample. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31(1), 7–26. View

Taillieu, T. L., Brownridge, D. A., Sareen, J., & Afifi, T. O. (2016). Childhood emotional maltreatment and mental disorders: Results from a nationally representative adult sample from the United States. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 61(5), 376–384. View

Spinazzola, J., Hodgdon, H., Liang, L. J., Ford, J. D., Layne, C. M., Pynoos, R., & Kisiel, C. (2018). Unseen wounds: The contribution of psychological maltreatment to child and adolescent mental health and risk outcomes. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 6(S1), S18- S28. View

Crow, T., Cross, D., Powers, A., & Bradley, B. (2014). Emotion dysregulation as a mediator of the relation between childhood emotional abuse and current depression. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38(3), 394–403. View

Humphreys, K. L., LeMoult, J., Wear, J. G., Piersiak, H. A., Lee, A., & Gotlib, I. H. (2020). Child maltreatment and depression: A meta-analysis of studies using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Psychological Medicine, 50(7), 1181–1192. View

Teicher, M. H., & Samson, J. A. (2016). Annual research review: Enduring neurobiological effects of childhood abuse and neglect. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57(3), 241–266. View

Linehan, M. M. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. Guilford Press. View

Zielinski, D. S., Anderson, K. L., & Parker, C. (2022). The enduring impact of emotional abuse on adult functioning: A population-based study. Traumatology, 28(3), 275–286.

Matlow, R. B., & Cote, S. M. (2021). The long-term effects of childhood maltreatment on adult mental disorders, substance use, and physical health: Results from a nationally representative sample. Child Abuse & Neglect, 117, 105–124.

Dube, S. R., Anda, R. F., Felitti, V. J., Edwards, V. J., & Croft, J. B. (2003). Childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction and the risk of illicit drug use: The adverse childhood experiences study. Pediatrics, 111(3), 564–572. View

Sinha, R. (2008). Chronic stress, drug use, and vulnerability to addiction. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1141(1), 105–130. View

Trickett, P. K., Noll, J. G., & Putnam, F. W. (2011). The Impact of Sexual Abuse on Female Development: Lessons from a Multigenerational, Longitudinal Research Study. Development and Psychopathology, 23, 453-476. View

Gauthier-Duchesne, A., Hébert, M., & Blais, M. (2017). Child psychological maltreatment and emotional and behavioral problems: The role of parents and peer relationships. Child Abuse & Neglect, 69, 44–53.

Perry, B. (2006). Applying the neurosequential model of therapeutics to trauma-informed social work practice. Childhood Neurobiology and Trauma Journal. View

Schore, A. N. (2012). The science of the art of psychotherapy. W. W. Norton & Company. View

Rothschild, B. (2000). The Body Remembers: The Psychophysiology of Trauma and Trauma Treatment. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company. View

Fares-Otero, N. E., Carranza-Neira, J., Womersley, J. S., et al. (2025). Child maltreatment and resilience in adulthood: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 55, Article e163. View

SAMHSA. (2014). SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. View

van der Kolk, B. A. (2005). Developmental trauma disorder: Toward a rational diagnosis for children with complex trauma histories. Psychiatric Annals, 35(5), 401–408. View

Comas-Díaz, L. (2016). Racial trauma recovery: A race informed therapeutic approach to racial wounds. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 44(2), 82–98. View

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). View

Kessler, R. C., McLaughlin, K. A., Green, J. G., Gruber, M. J., Sampson, N. A., Zaslavsky, A. M., & Williams, D. R. (2010). Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. British Journal of Psychiatry, 197(5), 378–385. View

Hildyard, K. L., & Wolfe, D. A. (2002). Child neglect: Developmental issues and outcomes. Child Abuse & Neglect, 26(6- 7), 679–695. View

Baglivio, M. T., Epps, N., Swartz, K., Huq, M. S., Sheer, A., & Hardt, N. S. (2014). The predictive validity of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) to juvenile recidivism. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 12(4), 376–390. View

Duke, N. N., Pettingell, S. L., McMorris, B. J., & Borowsky, I. W. (2010). Adolescent violence perpetration: Associations with multiple types of adverse childhood experiences. Pediatrics, 125(4), e778–e786. View

CSWE. (2022). Educational Policy and Accreditation Standards for Baccalaureate and Master’s Social Work Programs. Council on Social Work Education. View

Bernstein, D. P., & Fink, L. (1998). Childhood Trauma Questionnaire: A retrospective self-report manual. Psychological Corporation. View

Cloitre, M., Courtois, C. A., Charuvastra, A., Carapezza, R., Stolbach, B. C., & Green, B. L. (2012). The ISTSS expert consensus treatment guidelines for complex PTSD in adults. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 25(6), 489–495. View

Schiele, J. H. (1997). The contour and meaning of Afrocentric social work. Journal of Black Studies, 27(6), 800–819. View

Asante, M. K. (1998). Afrocentricity: The theory of social change. African American Images.