Journal of Social Work and Welfare Policy Volume 3 (2025), Article ID: JSWWP-178

https://doi.org/10.33790/jswwp1100178Research Article

Addressing the Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Racial Disparity: A Scoping Review of Breast Cancer Awareness and Screening Initiatives for Black Women

Dorie J. Gilbert*, PhD, Beverly A. Spears, PhD, Jean M. Kessler, MSW, Crystal R. Bell, MSW, Alexis D. Stewart, MSW, Lateria N. Hughes, MSW, Taytana Brown, MSW, & Renata C. Smith, BS

Department of Social Work, Prairie View A&M University, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Dorie J. Gilbert, PhD, Professor, Department of Social Work, Prairie View A&M University, United States.

Received date: 04th December, 2025

Accepted date: 23rd December, 2025

Published date: 26th December, 2025

Citation: Gilbert, D. J., Spears, B. A., Kessler, J. M., Bell, C. R., Stewart, A. D., Hughes, L. N., Brown, T., & Smith, R., C., (2025). Addressing the Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Racial Disparity: A Scoping Review of Breast Cancer Awareness and Screening Initiatives for Black Women. J Soci Work Welf Policy, 3(2): 178.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC) is widely considered the most aggressive and challenging breast cancer subtype, and it also disproportionately impacts U. S. Black women, who are nearly twice as likely to be diagnosed with TNBC as their White counterparts. However, general breast cancer awareness initiatives, while widespread and credited with overall reduced mortality, may lack specific messaging and techniques to increase TNBC and general screening awareness among Black women. We aimed to map the current extent and nature of breast cancer awareness and mammography screening interventions for U. S. Black women. Further, we explored the extent to which those programs addressed TNBC. Following a refined search strategy of published literature between 2015-2025, we identified 18 studies to examine for program aims, program components, and strategies for raising awareness. We found that while all selected studies reflected overall gains in increasing awareness and screening for Black women, only one-third of the programs included content related to TNBC, indicating a potential gap in awareness initiatives. We conclude with recommendations on how social work practice can promote awareness of TNBC and breast cancer screening among Black women and discuss critical policy implications, including ongoing debates regarding national screening guidelines aimed at reducing TNBC mortality rates among Black women.

Background

While overall incidence rates for breast cancer in the U. S. are rising, mortality rates have declined due to improvements in detection and treatment [1]. However, a significant racial disparity exists for Black women, who have a 5% lower breast cancer incidence than White women, but a 38% higher mortality rate [2]. This disparity is primarily due to Black women’s prevalence of delays in diagnosis and higher rates of diagnosis with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), a more aggressive and less treatable breast cancer subtype because it lacks the three receptors--estrogen, progesterone, and HER2--that many hormone-based therapies target [2,3]. Compared to their White counterparts, Black women with breast cancer are nearly twice as likely to be diagnosed with TNBC, often at younger ages and with worse prognoses [3,4], indicating an urgent need to prioritize early detection. Moreover, diagnosis at later stages correlates with low levels of knowledge about breast cancer and TNBC risks for Black women, which limits successful treatment [5].

A disproportionate number of Black women experience structural barriers to early diagnosis, including a lack of accessible and affordable healthcare [5-7]. Consequently, 57% of breast cancers in Black women are diagnosed at a localized stage, compared to 67% in White women [3]. While many Black women understand the need for regular mammograms, they may face obstacles, such as fear of painful procedures, appointment inconvenience, medical and provider mistrust, and lack of awareness and perception of their personal risk [6,8]. Moreover, once recommended therapies are available, financial challenges such as childcare costs, transportation, and time off work can hinder women from completing a full course of clinical treatments [9].

In addition to sociocultural challenges, genetic predispositions play a role in the mortality disparity. Cancer genetic studies have investigated ancestry links between TNBC and women of African descent [10]. While TNBC remains an enigmatic cancer subtype, research investigations continue to explore the relative contributions of both biologic and non-biologic factors influencing TNBC clinical outcomes [11], as well as emerging treatment options [12]. What is known is that Black women are 30% more likely to die from TNBC tumors when compared to White women with the same diagnosis [3]. This disparity is linked to Black women’s relatively lower rates of surgery, lower awareness, and a lack of support to seek out genetic counseling and testing [13]. Compounding this issue, they face a reduced likelihood of being referred for genetic testing by physicians, even when they meet high-risk criteria [13].

Breast cancer awareness initiatives are widespread and credited with overall reduced mortality [14]; however, persistent gaps in prevention messages remain among Black women [13,15,16]. Targeted awareness campaigns and interventions to increase screenings are paramount to reducing the mortality disparity for Black women. Moreover, because TNBC's aggressive nature is typically diagnosed at a younger age and lacks therapeutic targets found in other subtypes, campaigns focused on Black women should address TNBC's heightened risk profile while also providing information about its nascent therapy options [12]. We explore the range of programs aimed at improving breast cancer awareness and mammography screening for Black women and further review the extent to which those programs focused on TNBC.

Methods

Study Design

We considered a scoping review method a good fit to address our exploratory research question: What is the extent and nature of breast cancer awareness and screening interventions targeting U. S. Black women in community settings? The methodology employed a broad focus, aligning with the use of scoping reviews for exploratory studies [17]. Consistent with the minimal requirements for some scoping reviews [18], our focus did not include formal quality assessments of the studies. The methods followed the general guidelines of specifying a research question, selecting relevant studies, and charting the data. The review was guided by the PCC (Population, Concept, Context) framework [19]. We included studies if they targeted U.S. Black women (population), addressed cancer awareness and screening promotion programs (concept), and targeted women in community settings (context). Our primary goal was to conduct descriptive mapping of the existing literature and restrictions were not placed on the type or quality of the outcomes reported.

Search strategy

We completed a comprehensive search in November 2025 across the following electronic databases: PubMed, Web of Science (Core Collection), and CINAHL, MEDLINE, and Academic Search Ultimate (all via the EBSCOhost platform) to identify relevant studies. Additionally, we searched gray literature from targeted websites of relevant organizations, academic databases, and government sites. Inclusion was restricted to reports of programs or interventions, including published conference abstracts and peer-reviewed publications. Search terms included combinations of the following: "Black" OR "African American", "breast cancer", "awareness campaigns" OR "interventions", "breast cancer screening" OR "mammography". We established a publication range between January 2015 and August 2025, given that 2015 marked a decade after the medical community began to realize that TNBC disproportionately affected Black women and young women. We limited the search to the English language and selected studies based on their relevance to the topic and focus on outcomes related to increased awareness and mammography screening among U.S. Black women. We included programs that targeted Black women combined with Hispanic/Latina and Black women or Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) in community settings if statistics on the sub-population of Black participants were provided. We excluded review articles (narrative, scoping, systematic, meta-analysis, and meta-synthesis). Additional exclusion criteria included:

-Articles reporting evidence related to Black women outside of the U.S.

--Articles reporting studies on women currently living with breast cancer

--Articles published before January 2015 and after September 2025

Screening Process

The study protocol occurred in stages. First, three reviewers (the first, fourth, and fifth authors) screened the titles from the databases, guided by the eligibility criteria. Records retrieved from the initial database search and gray literature scan yielded 683 articles. We exported the list directly into a single Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. After removing duplicates and following title screening, 73 studies were eligible for inclusion in the abstract or full-text screening. Of these, 43 studies were excluded, leaving 30 studies for full review. Of these, we identified 18 articles for data extraction.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

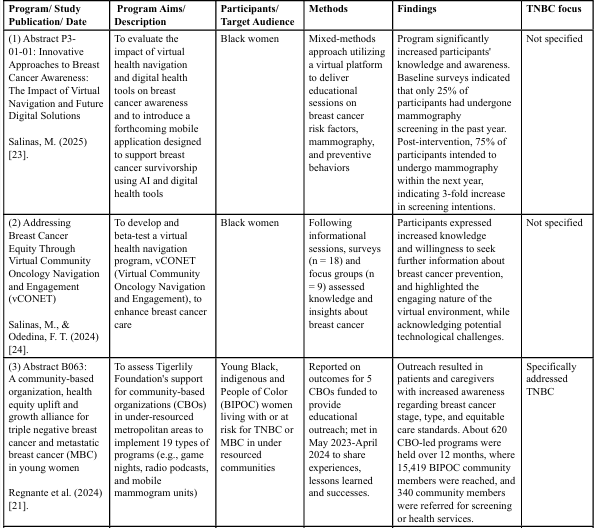

We present the eighteen included studies in Table 1. The studies, labeled as 1 through 18, were published between 2015 and September 2025 and are organized in chronological order in a simplified data charting form. We captured essential information, including publication title, authorship, year of publication, study aims, targeted population, methods, reported findings, and whether the study addressed TNBC. Selected studies were documented in both published conference abstracts and full-length peer-review articles. All studies reported evidence of outreach programs to U.S. Black women for breast cancer awareness and screening in the context of a community or clinical setting. While we included methods and findings in the charting, we did not evaluate these components in this study; rather, our aim was to explore gaps in the literature regarding awareness initiatives focused on TNBC. Six of the eighteen studies reflected aspects of TNBC that were included or related to the outreach aims or program components. In the following section, our discussion centers on the variations and synthesis of the selected studies, including overlapping themes and details of how aspects of TNBC were featured.

Discussion

The findings present a general overview of published work on studies that increase awareness and promote breast cancer screening among U.S. Black women. The studies revealed several approaches to health education delivery, mainly focusing on innovative navigation strategies to connect women to screening appointments, including the exploration of virtual navigation in more recent studies. A general theme across the studies is the effective use of culturally tailored strategies that have been recommended in the literature [8], such as the use of lay healthcare providers, collaborations with community networks and organizations, and embedding outreach efforts, such as mobile mammograms, in communities to reduce screening barriers. Further, many of the interventions specifically targeted geographical locations with high rates of late diagnosis and breast cancer mortality. Although an analysis of the methods and findings is beyond the scope of this paper, it is important to note that all studies reported consistently positive outcomes in terms of raising awareness and promoting screening behavior.

Regarding our secondary question, we found six studies that addressed TNBC in some manner. Three of the six studies (#3, #6, #9) specifically targeted increased awareness or emphasis on TNBC [20-22]. Regnante et al. [21] report on the Tigerlily Foundation, a leading global organization, and its focus on TNBC awareness with five community-based organizations (CBOs) in underresourced metropolitan areas to implement 19 types of programs (e.g., game nights, radio podcasts, and mobile mammogram units). The outreach resulted in patients and caregivers with increased awareness regarding breast cancer stage, type, and equitable care standards.

Rodriguez et al. [22] detail the work of the National Witness Project, an evidence-based program designed to reduce breast and cervical cancer disparities among Black women. The article discusses how the program updated the curriculum content to include new science, including risk factors related to TNBC. This update provided women with information about the optional use of medical screenings for TNBC diagnosis in high-risk African American women and advised them on the relationship between TNBC and lactation in African American women. In the third study, Padamsee et al. [20] report on the Turning the Page on Breast Cancer program, which aimed to reach women in geographical areas identified as having the highest rates of TNBC, late-stage breast cancer, and a significant population of Black residents. Women were provided risk information and education at virtual and in-person community events and through a community-friendly website.

Two other studies (#4 and #7), both in 2023, included references or content related to TNBC or genetic risks [25,26]. Dash et al. [25] focused on women's completion of genetic risk assessments, including the collection of information on TNBC diagnosis, and Hopewell et al. [26] addressed TNBC in the literature review of the abstract. The sixth study (#8) reports on the Program for the Elimination of Cancer Disparities (PECaD), which developed a breast cancer community partnership in 2007 to improve awareness of prevention and breast health services, build trust, develop strategies to help patients keep appointments, and support adherence to routine screening [27]. Over the years, the PECaD engaged bench scientists to address the excess risk of TNBC in African American women. Because TNBC only gained widespread attention around 2005, it is not surprising that, except for Rodriguez et al. [22], the more recent studies have focused on TNBC compared to earlier work. While the other programs might have included TNBC content, evidence of such was not available in the retrieved content.

Not all studies provided details on educational content or curriculum materials, and for most of the studies, specific details on TNBC or educational content may not have been relevant to the design. Several studies were specifically designed to test the delivery of novel processes, rather than educational content, such as the effectiveness of delivering awareness messages through mass media [32,36], live performances [30], mammogram parties [29], spiritual framing [31], and daughter-initiated conversations [34]. Other programs examined innovative navigation systems [28,33,35,37] or the utility of digital tools [23,24].

Additionally, our inclusion of published abstracts (n=6) among the 18 selected studies in some cases did not allow us access to more detailed information about the educational content; however, we reviewed full articles for references to TNBC. Of note, all studies reflected positive findings and novel approaches to breast health promotion for Black women. Thus, these collective achievements contributed to increased rates of early detection, a critical factor in reducing racial disparity in breast cancer mortality, regardless of whether TNBC content was present. However, because the disparity in breast cancer mortality for Black women is partly linked to higher rates of TNBC diagnosis [3], lack of information about TNBC results in missed opportunities for risk mitigation and worsening racial disparities in cancer outcomes. Increased education is especially needed for young Black women, as recent research reinforces the persistent findings of their low levels of perceived risk of developing cancer, knowledge gaps about risk factors, and lack of awareness of cancer recommendations targeted towards women under the age of 40 [16].

While the TNBC subtype is known to have fewer treatment options, the American Breast Cancer Research Foundation [38] reports on advancements and expanding treatments. Thus, Black women need to be fully informed not only about their relative risks but also about the rapidly accelerating research on this subtype [12], including emerging data on protective factors. Moreover, women’s self-agency is dependent on comprehensive health information. Overall, there is a gap in evidence regarding interventions that address TNBC awareness among Black women, highlighting the necessity for increased programming and research. The selected studies revealed diverse methods for achieving breast cancer screening among Black women. We did not analyze the methods and outcomes; however, the general evidence helps identify gaps for future research. Additionally, our defined search strategy limits the scope of our findings, potentially leading to the omission of some studies. Notwithstanding, our review uncovered significant insights that inform future social work practice and policy initiatives.

Implications

Implications for Practice

Given that health equity is a focus of social work, practitioners should be aware of tailored cancer awareness campaigns that effectively overcome barriers to early detection experienced by many Black women. In general, we offer the following recommendations for social work practice:

(a) Become familiar with the various culturally responsive intervention strategies used to foster awareness and promote screening procedures for Black women, including the various approaches used in the selected studies highlighted in Table 1. Program components should employ language and imagery that resonate with Black women. Padamsee et al. [20] recommend that programs address specific cultural beliefs and experiences to reduce fear and mistrust, particularly regarding topics related to TNBC.

(b) Consider the benefit of partnerships and developing collaborations between community organizations (e.g., churches, community businesses, civic organizations) and healthcare educators to help facilitate widespread outreach. Logistical supports are needed to eliminate screening barriers, such as transportation and costs [39].

(c) Understand the need for health literacy in awareness programs targeting Black women. To make informed decisions about their health, women benefit from campaigns that use clear language and visual aids to explain TNBC, screening guidelines, and treatment options.

(d) Support community-based programs that humanize the disease and reduce stigma, such as peer-to-peer sharing, performances, and storytelling from women living with breast cancer, especially those living with TNBC. Such narrative approaches normalize screening behaviors [22].

(e) Consider strategies that utilize Black radio and social media platforms. Young Black breast cancer survivors emphasized the importance of social media and videos for raising awareness [40], suggesting that social media is an underutilized conduit of health education.

Implications for policy

Paskett et al. [41] emphasize the importance of targeted public health initiatives in enhancing breast cancer outcomes for Black women. Social work policy professionals and practitioners aligned with federal, state, and local health policymakers should be aware of the following recommended policy initiatives:

(a) Enhancing Equitable Access to Care: Institutions should fund and implement culturally responsive patient navigation programs to assist women in overcoming structural barriers, such as transportation, financial constraints, and appointment coordination. Initiatives aimed at increasing mammography screening rates should also focus on expanding health insurance coverage and enhancing patient-provider communication [39].

(b) Advocating for expansion of federal programs: For example, the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP) is a federal program administered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] that provides low-cost breast and cervical cancer screenings to low-income, uninsured, and underinsured women. In program year 2022, this initiative diagnosed over 2,100 cases of invasive breast cancer [42].

(c) Amending Screening Guidelines: Given the unique aspects of TNBC incidence rates and the earlier onset with Black females, social work policymakers and practitioners should be aware of the national debate on age-adjusted recommendations for initiating breast cancer screening [43]. In a recent publication, researchers discuss the WISDOM Study (Women Informed to Screen Depending On Measures of risk), a landmark clinical trial designed to end the "one-size-fits-all" debate in breast cancer screenings [44]. The study’s findings support the move toward personalized screening in light of the nearly 40% higher mortality rate and the prevalence of aggressive TNBC in Black women.

(d) Expanding Genetic Screening: Social work policy professionals and practitioners can support proposals for universal testing, which researchers recommend considering the higher prevalence of genetic determinants for Black women [45].

Conclusion

Our scoping review sought to map the existing literature on studies which aimed to increase breast cancer awareness and screening for U. S. Black women, and the selected studies provided critical information on the extent and nature of such programs. Tailored prevention programs are key to addressing the urgent health inequities for breast cancer among Black women, and social work practitioners and policymakers are well-positioned to emphasize the importance of early detection and regular screening, along with TNBC-specific information. Furthermore, culturally relevant education is crucial in overcoming structural and biological barriers that lead to delayed screenings and advanced-stage diagnoses. Social workers must be at the forefront, translating awareness into action, linking individuals to the comprehensive psychosocial resources, and advocating for needed policy changes. Most importantly, the profession must acknowledge that, with respect to breast cancer, Black women face a different landscape, and multi-level social work responses must reflect their reality.

Competing Interests:

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

National Cancer Institute. (2023). Breast Cancer Statistics. View

American Cancer Society (2024). Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2024-2025. View

American Cancer Society (October 6, 2022). ACS reports: Black women still more likely to die from breast cancer. View

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., Wagle, N. S., & Jemal, A. (2024). Cancer statistics, 2024. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 74(1), 12–49. View

Williams, D. R., Kothari, A., Lawson, S. H., Shulman, L. N., Lee, C. I., & Onega, T. (2022). Structural racism and triple negative breast cancer among Black and White women in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 112(12), 1739–1748.

Aleshire, M. E., Adegboyega, A., Escontrías, O. A., Edward, J., & Hatcher, J. (2021). Access to Care as a Barrier to Mammography for Black Women. Policy, Politics & Nursing Practice, 22(1), 28–40. View

Chopra, S. P., Roy, H. K., & Sharma, M. C. (2022). Structural Racism and Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Among Black and White Women in the United States. Cancer Prevention Research, 15(3), 209–218.

Jackson, T., Wahab, R. A., Bankston, K., & Mehta, T. S. (2024). Raising Cultural Awareness and Addressing Barriers to Breast Imaging Care for Black Women. Journal of Breast Imaging, 6(1), 72–79. View

Jatoi, I., & Sledge, G. W. (2018). Racial disparities in breast cancer: A cause for national shame. Cancer, 124(17), 3460- 3462.

Jia, G., Ping, J., Guo, X., Yang, Y., Tao, R., Li, B., Ambs, S., Barnard, M. E., Chen, Y., Garcia-Closas, M., Gu, J., Hu, J. J., Huo, D., John, E. M., Li, C. I., Li, J. L., Nathanson, K. L., Nemesure, B., Olopade, O. I., ... Zheng, W. (2024). Genome wide association analyses of breast cancer in women of African ancestry identify new susceptibility loci and improve risk prediction. Nature Genetics, 56(5), 819–826. View

Newman, L., & Mitchell, E. (2023). Disparities in triple negative breast cancer. Journal of the National Medical Association, 115(2), S8–S12. View

Riaz, F., Gruber, J. J., & Telli, M. L. (2025). New Treatment Approaches for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book, 45(3), e481154. View

Reid, S., Cadiz, S., & Pal, T. (2020). Disparities in Genetic Testing and Care among Black women with Hereditary Breast Cancer. Current Breast Cancer Reports, 12(3), 125–131. View

Kwong, A., & Kim, S. (2018). The role of awareness campaigns in improving breast cancer outcomes. Journal of Cancer Policy, 18, 1–5.

Ademuyiwa, F. O., Kothari, A., Kothari, V., Ma, M., Zuo, T., Hageman, L., Hageman, H., & Bierut, L. J. (2021). Racial disparities in physician-reported practices and perceived barriers to genetic counseling and testing for breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 39(36), 4055–4066.

Ilodianya, C. and Williams, M.S. (2025). Young black women's breast cancer knowledge and beliefs: A sequential explanatory mixed methods study. J. of Racial Ethnic Health Disparities. Dec;12(6):4144-4150. View

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. View

Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), Article 69. View

Peters, M. D. J., Godfrey, C. M., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Parker, D., & Soares, C. B. (2015). Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. International Journal of Evidence Based Healthcare, 13(3), 141–146. View

Padamsee, T. J, Stover, DG, Tarver, W.L. (2023). Turning the Page on Breast Cancer in Ohio: Lessons learned from implementing a multilevel intervention to reduce breast cancer mortality among Black women. Cancer. 129(S19): 3114-3127. View

Regnante, J. M., Pratt-Chapman, M. L., Paulicin, B., Leader, A., Leach, V., Cooper, L. A., Steele, S., & Karmo, M. (2024). Abstract B063: A community-based organization, health equity uplift and growth alliance for triple-negative breast cancer and metastatic breast cancer in young women. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention, 33(9_Supplement), B063-B063. View

Rodriguez, E. M., Jandorf, L., Devonish, J. A., Saad-Harfouche, F. G., Clark, N., Johnson, D., Stewart, A., & Widman, C. A. (2020). Translating new science into the community to promote opportunities for breast and cervical cancer prevention among African American women. Health Expectations, 23 (2), 433- 440. View

Salinas, M. (2025). Abstract P3-01-01: Innovative Approaches to Breast Cancer Awareness: The Impact of Virtual Navigation and Future Digital Solutions. Clinical Cancer Research, 31(12_ Suppl), P3-P3-01–01. View

Salinas, M. & Odedina, F. T. (2024). Addressing Breast Cancer Equity Through Virtual Community Oncology Navigation and Engagement Control, 31, Article (vCONET). Cancer 10732748241264711. View

Dash, C., Mills, M. G., Jones, T. D., Nwabukwu, I. A., Beale, J. Y., Hamilton, R. N., Hurtado-de-Mendoza, A., & O'Neill, S. C. (2023). Design and pilot implementation of the Achieving Cancer Equity through Identification, Testing, and Screening (ACE- ITS) program in an urban under-resourced population. Cancer, 129(S19), 3141–3151. View

Hopewell, N., Kazar, B., Strong, M., & Smith, K. (2023). Abstract A014: Connecting with Black patients through targeted, breast cancer messaging in the clinic setting. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. View

Colditz, G. A. (2022). Abstract IA-03: Making progress, together: An inclusive, broad-based approach to reducing excess burden of breast cancer among African American women in St Louis - with lessons for national implementation. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 31(1_Supplement), IA-03-IA-03. View

Richman, A. R., Torres, E., Wu, Q., & Kampschroeder, A. P. (2020). Evaluating a Community-Based Breast Cancer Prevention Program for Rural Underserved Latina and Black Women. Journal of Community Health, 45(6), 1205–1210. View

Allgood, K. L., Hunt, B., Kanoon, J. M., & Simon, M. A. (2018). Evaluation of Mammogram Parties as an Effective Community Navigation Method. Journal of Cancer Education: The official journal of the American Association for Cancer Education, 33(5), 1061–1068. View

Davis, C., Darby, K., Moore, M., Cadet, T., & Brown, G. (2017). Breast care screening for underserved African American women: Community-based participatory approach. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 35(1), 90–105. View

Best, A. L., Spencer, S. M., Friedman, D. B., Hall, I. J., & Billings, D. (2016). The Influence of Spiritual Framing on African American Women’s Mammography Intentions: A Randomized Trial. Journal of Health Communication, 21(6), 620–628. View

Mayfield-Johnson, S., Fastring, D., Fortune, M., & White Johnson, F. (2016). Addressing Breast Cancer Health Disparities in the Mississippi Delta Through an Innovative Partnership for Education, Detection, and Screening. Journal of Community Health, 41(3), 494–501. View

Torres, E. T. & Richman, A. R. (2016). Abstract A34: Using a community-based breast health intervention to reduce structural barriers in accessing breast cancer screening services among underserved rural Latina and black women in Eastern North Carolina. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 25(3_Supplement), A34–A34. View

Mosavel, M., & Genderson, M. W. (2016). Daughter-Initiated Cancer Screening Appeals to Mothers. Journal of cancer education: The official journal of the American Association for Cancer Education, 31(4), 767–775. View

Calfa, C. J., Wilkinson, J. G., Williams, M.M., Pann, J. M., Yehl, A., Hoogenbergen, S. E., & Ivory, A. D. (2015). Abstract: Impact of a culturally syntonic door-to-door breast cancer early detection intervention. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Seventh Annual AACR San Antonio Breast Cancer Convention of the CTRC Cancer Research (Chicago, Ill.), 75(9_Supplement), P1- P1-17–03. 2015; 75 (9 Suppl): Abstract nrP1 17-03 View

Hall, I. J., Johnson-Turbes, A., Berkowitz, Z., & Zavahir, Y. (2015). The African American Women and Mass Media (AAMM) campaign in Georgia: Quantifying community response to a CDC pilot campaign. Cancer Causes and Control, 26(5), 787–794. View

Haynes, D., Hughes, K., Haas, M. et al. (2023). Breast Cancer Champions: A peer-to-peer education and mobile mammography program improving breast cancer screening rates for women of African heritage. Cancer Causes Control 34, 625–633. View

American Breast Cancer Research Foundation (Feb 20, 2025). Three important things to know about triple negative breast cancer. View

Agrawal, P., Chen, T. A., McNeill, L. H., Acquati, C., Connors, S. K., Nitturi, V., Robinson, A. S., Martinez Leal, I., & Reitzel, L. R. (2021). Factors Associated with Breast Cancer Screening Adherence among Church-Going African American Women. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), 8494. View

Huq, M. R., Woodard, N., Okwara, L., McCarthy, S., & Knott, C. L. (2022). Recommendations for breast cancer education for African American women below screening age. Health Education Research, 36(5), 530–540. View

Paskett, E. D., Henry, L. T., Dean, K. K., & Harfoush, S. R. (2018). Disparities in breast cancer tumor characteristics, treatment, time to treatment, and survival probability among African American and white women. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 168(3).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2025). National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP). View

Chen, T., Kharazmi, E., & Fallah, M. (2023). Race and Ethnicity Adjusted Age Recommendation for Initiating Breast Cancer Screening. JAMA Netw Open. 2, 6(4): e238893. View

Esserman, L. J., Fiscalini, A. S., Naeim, A., van’t Veer, L. J., Kaster, A., Scheuner, M. T., LaCroix, A. Z., Borowsky, A. D., Anton-Culver, H., Olopade, O. I., Esserman, J., Lancaster, R., Madlensky, L., Blanco, A. M., Ross, K. S., Goodman, D. L., Tong, B. S., Hogarth, M., Heditsian, D., ... Eklund, M. (2025). Risk-based vs annual breast cancer screening: The WISDOM randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 334(22). Advance online publication. View

Ademuyiwa, F. O., Ademuyiwa, I. A., & Agboniro, J. (2024). Universal genetic counseling and testing for Black women: A risk-stratified approach to addressing breast cancer disparities. Cancer, 130(3), 335–340.